Health

Vol.5 No.3(2013), Article ID:28617,9 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.53056

“I screamed for help”: A single case study of one sister’s experiences with formal psychiatric care when her brother became mentally ill

![]()

1Faculty of Health Science, Nord-Trøndelag University College, Namsos, Norway; *Corresponding Author: lars.lilja@hint.no

2Department of Health Sciences, Mid-Sweden University, Östersund, Sundsvall, Sweden

3Center for Care Research Mid-Norway, Steinkjer, Norway

Received 25 January 2013; revised 27 February 2013; accepted 2 March 2013

Keywords: Content Analysis; Mental Health; Nursing; Siblings; Single Case Study

ABSTRACT

Studies have shown that the quality of the relationship between siblings has great significance for the mentally ill sibling’s overall quality of life. Sibling relationships may be particularly important because few adults with severe mental illness have children. As parents grow older, adult children are expected to support their sibling with mental illness when their parents are no longer able to do so. The sibling relationship has the potential to be one of the most significant relationships for adults with schizophrenia. The aim of this paper is to present a case study of a sister’s experiences and needs in her contact with psychiatric care. This single case study was designed and the informant was recruited because of her value in maximizing what we can learn about being a sibling to a person with mental illness. Data were collected through four in-depth, semi-structured, repeated interviews during a two-year period, and were interpreted and analyzed through content analysis. Three major topics were discussed: 1) Anna’s brother’s time with formal psychiatric care; 2) Anna’s feelings and emotions; and 3) Anna’s view of her contact with psychiatric care. The findings indicated a sibling’s need for attention, support, and understanding from the formal caregivers. Participation in our study was one of the first opportunities she had to talk about her relationship with formal psychiatric care. An open dialogue may help siblings to manage their situations.

1. INTRODUCTION

This single case study, which is a part of a larger study, was designed to examine experiences of family members of mentally ill patients and their relationship with formal psychiatric care. In the literature, the relationship between staff and family members is described as important [1,2]. However, empirical studies show that mental health staff often ignore family members’ knowledge and tend to avoid giving information about the patient’s state [3]. For example, in Saunders and Byrne’s [4] investigation, family members expressed clearly that they wished to be involved in the planning of their ill relative’s treatment. They also, in their contact with the formal psychiatric caregivers, long to be met with respect, be taken seriously, and experience involvement in care. Instead, they are met with disrespect and no serious consideration [5,6], and are seldom allowed to make treatment decisions [7].

Elsewhere in this project, actors with or around people suffering from severe mental illness describe their experiences. Findings show that staff had a strong tendency to find themselves in double-bind situations between healthy family members and the person who suffers from mental illness [8] and that family members’ relationships to formal psychiatric care were characterized by a struggle for power [9]. When comparing staffs’ views to those of family members, the need to interview the person who suffered from mental illness became obvious. In our third study [10] we asked psychiatric patients to narrate stories about their view of their family’s participation in their care and their view of how to implement their families’ resources. Findings indicate that families are often viewed as a potential resource but how and to what extent they should participate must be an individual judgment in which both parties’ needs must be taken into consideration.

The incongruence in needs suggests that both the families’ and formal psychiatric care staff’s needs seem to blur the uniqueness of the mental illness sufferer and obstruct both parties’ ability to see the patient. Therefore, to increase our knowledge it is important to add depth to our studies about family members’ situations and to try to understand the experience of one sibling and the effect formal care’s actions have on the sibling’s well-being. It is important to investigate siblings because few studies have been done with this focus and because the siblings struggle with their own fear of possibly inheriting schizophrenia and with their lack of understanding of formal care.

Studies e.g. [11], have shown that the quality of the relationship between siblings has great significance for the mentally ill sibling’s overall quality of life. Gender plays an important role with sisters more likely than brothers to provide support and have close ties with a mentally ill sibling [12,13]. On the basis of their accumulated experiences, siblings formulate beliefs about the sick brother or sister. According to Robinson [14], the strengths of family ties are closely connected to the amount of control the mentally ill sibling has over his or her actions and symptoms—the better the control the weaker the ties. Sibling relationships may be particularly important because few adults with severe mental illness have children. As parents grow older, adult children are expected to support their sibling with mental illness when their parents are no longer able to do so [15]. According to Smith and Greenberg [16], the sibling relationship has the potential to be one of the most significant relationships for adults with schizophrenia. Therefore, to increase our knowledge, the aim of this paper is to present a case study of a sister’s experiences and needs in her contact with her brother’s psychiatric care.

2. METHODOLOGY

A qualitative approach was chosen in this study because when studying humans’ experiences and understanding their lives and the world, it seems important to talk to them with the purpose of trying to understand the world from their point of view. A person’s lived experience can be captured only through letting them narrate their own stories. Therefore, the data from which the interpretation originates represents personal statements/ stories about personal experiences, which are always to be seen as unique.

2.1. Study Design

This in-depth single case study used a naturalistic, qualitative methodology to explore one sister’s experience with voluntary and involuntary psychiatric care in connection to her brother’s mental illness. Naturalistic inquiry is grounded in the belief that knowledge can be developed inductively using methods that are emergent and flexible to change [17]. The unique case could be identified as a way to understand the phenomenon of interest. It is like an exciting mystery that one seeks to understand with the intention of catching its complexity in the unique as well as the general [18]. In spite of the fact that single case studies cannot be generalized to the population, we can learn much that is general from single cases [18, p. 85]. A study that is based on a particular case must be seen as microscopic and not in itself representative. Therefore, the challenge is in the researcher’s ability to locate the global in the local [19]. The key inquiry of this research was to learn from Anna’s experiences as a sister to a brother who suffers from severe long-term mental illness with a focus on her contact with formal psychiatric care.

2.2. Data Collection

Anna (fictitious name) is a sibling, in her mid-30s, to a younger mentally ill brother. She works as an assistant nurse at a hospital in a town in the middle of Sweden. Her father died about 13 years ago. Her brother is Anna’s only sibling. She describes their relationship as “warm, with elements of sibling conflicts”. Her relationship with her mother is described as “good, with close contact with each other”. At the time of her brother’s illness, he was in his upper teens and their father had recently passed away. Anna had moved into her own apartment in a town about 50 kilometers from her mother and brother. When the brother presented symptoms, both Anna and her mother thought it was just a question of teenage revolt or a reaction to his father’s death. Over time it became obvious that Anna’s brother did not feel mentally well, which was the beginning of a “protracted contact full of conflicts with formal psychiatric care”. At the time of the start of this study, the brother’s hospital care had lasted more than ten years, most of the time involuntary.

Anna was recruited, not because she was typical but rather because she was valuable in maximizing what we can learn about the phenomenon of being a sibling to a person with mental illness. A colleague at the hospital who was acquainted with both Anna’s and her brother’s situations and with our research contacted Anna and informed her about our project. Through her colleague, Anna contacted the first author (LMS) to learn about the study. The researcher explained the intent of it, emphasized the voluntary nature of participation, and confirmed that she could withdraw at any time for any reason. Anna was informed of her rights through informed consent procedures. Anna participated in four interviews in the course of two years. All four interviews were taperecorded with Anna’s permission and lasted between 70 and 90 minutes (320 minutes in total) and were transcribed verbatim by the first author. The Ethics Committee at Umeå University, Sweden, granted permission for the study (registration number 01 - 413).

As Anna was recruited on recommendation from her colleague and not from the researcher’s own knowledge, there was a risk that she might not live up to the researcher’s expectations. However, during the interview it became obvious that Anna met the requirements to share her experiences with the researcher to such an extent as to make viable a single case study designed to learn about the uniqueness of her situation. As Stake writes, “Sometimes, we are given (the case), even obligated to take it as the object of study” [18, p. 3]. Anna’s experiences presented unique opportunities for us to learn what it is like to be a sister to a mentally ill younger brother and to understand her contact with formal psychiatric care.

Data was collected through in-depth, semi-structured, repeated interviews. Repeated interviews help to build understanding between researcher and interviewee [20]. The interview was conducted as a conversation and the interview questions were formulated so relevant information was obtained on the subject, yet it was flexible enough to allow participants to respond and participate easily in a conversation, encouraging their own thoughts and feelings to emerge [21]. Using stories as a data collection method is supported by Sandelowski [22], who feels that the story gives important information about the individual who narrates (we are the stories we tell) and that a story includes, in itself, the past, the present, and the future. Interview questions focused on Anna’s experience as a sister and her experience and relationship with formal psychiatric care, in particular the ward staff. Anna was asked to narrate stories about the following themes: 1) her experiences and contact with the psychiatric caregivers; 2) her need of support and information; and 3) her opinion of how family members could best be used to support formal care.

2.3. Analysis

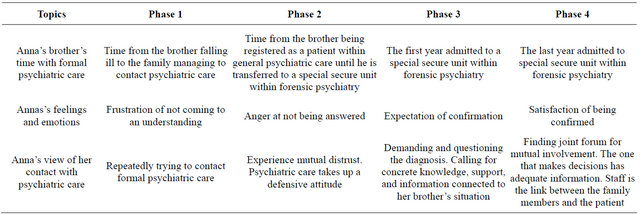

Audio-taped interviews were transcribed and analyzed using content analysis [23-25]. First, each text was read by the first (LMS), second (OH), and third (LL) authors to provide a sense of the whole and to generate ideas of how to analyze the text in more detail. These authors agreed that the following three topics were important: Anna’s brother’s time with formal psychiatric care, Anna’s feelings and emotions, and Anna’s view of her contact with psychiatric care. Second, each text was then read and analyzed regarding the content and topics listed above. In the second reading, four phases emerged from the text. Third, each text was again considered as a whole, and in the process four feelings emerged from the text: 1) frustration of not coming to an understanding; 2) anger for not being answered; 3) expectation of confirmation; and 4) satisfaction of being confirmed. Finally, findings of the analysis were considered by the second (OH) and third (LL) authors in order to address the question of trustworthiness and discuss possible interpretations until consensus was reached [23]. The interpretations were later presented to Anna, so-called “member checking”, to address the question of credibility [17,26]. Anna agreed with the authors’ interpretation of the frustration of not coming to an understanding, the anger about not being answered, the expectation of confirmation, and the satisfaction of being confirmed.

3. FINDINGS

Interviews with Anna provided rich data for learning about the complexities of being a sister to a mentally ill brother and her experiences of contact with formal psychiatric care. In the transcribed interviews, an obvious chronology emerged. Anna began her narrations with a description of her experiences when her brother became ill. The brother’s falling ill was an occasion that had a severe influence on the whole family and, according to Anna, was the start of her contact with formal psychiatric care. The second and third experiences are described as a “floating dialectic” in which experiences create needs and the management of these needs in turn creates experiences. Finally, Anna narrates about how needs can be satisfied and how through that her relationship with psychiatric care improved. Three major topics are described: 1) Anna’s brother’s time with formal psychiatric care; 2) Anna’s feelings and emotions; and 3) Anna’s view of her contact with psychiatric care. Table 1 gives a summary of Anna’s brother’s illness from when it first emerged to the time of the last interview.

3.1. Phase 1—The First Years

Frustration of not coming to understanding—contact with psychiatric care:

In her narrations, Anna tells us that her contact with formal psychiatric care has been a “little bit troublesome” during the years. During her brother’s first year of illness, Anna and her mother made frequent and fruitless efforts to try to get in contact with psychiatric care. Anna tells us how “during this three-year period we phoned around, we called the primary care, we called the emergency care···both mum and I. ···” When her brother’s behavior became even stranger and Anna experienced his mental health status as deteriorating, as “he was worse and worse, sicker and sicker”, she used every possible means to get him to the psychiatric hospital’s emergency department. Her brother was suspicious and paranoid and Anna got “desperate”, seeing no other way than lie to him. She said, “The only way to get him outside the door, into the car, was to lie”.

According to Anna, her hope was that if she managed to get him to the hospital, staff there would see how sick he was and how crazy his actions were and they would help him. If she managed to get him inside “the psychiatTable 1. Summary of Anna’s brother’s illness from when it first emerged to the time of the last interview.

ric walls,” she thought, they all would be safe. However, neither staff nor physicians listened to her or her stories about the family’s present situation. As Anna experienced it, they were not taken seriously. According to Anna, staff considered her brother healthy and without any problems, and they said that if he did not want to have any psychiatric treatment, formal psychiatric care could not do anything. Every time they visited the psychiatric hospital the result was the same: Anna’s brother walked away and she was left behind.

So it went each time—her brother left the hospital and Anna was left behind in her disillusionment. Anna felt that she was completely alone in the situation. Meanwhile, the situation back home escalated. Her brother’s actions become stranger and stranger and she felt sorry for both him and her mother, who lived with him. Anna, convinced that he was mentally ill, she often thought, Why him and not me? Her experiences with psychiatric caregivers told her it was meaningless to try to get psychiatric help. Finally, a neighbor who knew their situation contacted the hospital and said, “If you don’t do something now, he will kill both himself and his mother and sister”. The police came and transported him to the hospital. Anna experienced this event as stressful and painful. Anna said, “It was painful to see the force they used when they put him into the police car”.

3.2. Phase 2—The Years in General Psychiatry

Anger over not getting answers – contact with psychiatric care:

When Anna’s brother was at last admitted to psychiatric hospital care, the staff finally understood that he was mentally ill. Paradoxically, according to Anna, the staff began to accuse her and her mother, asking them, “Why did you not seek out psychiatric help earlier, and why have you not contacted us?” Such accusatory questions were humiliating and she often wondered how they could ask them of her.

Anna said she had a desire and hope that she would be permitted to be an active participant in her brother’s care. She fought for contact with both the staff and physicians and wanted to offer herself as a personal resource in his care. Anna stressed the importance of creating a dialogue between family and staff, “but no one asked us”. Anna said she felt that the staff who cared for her brother distrusted her. They showed no faith in either Anna or her mother, and their behavior caused her to experience anger and other negative feelings. For example, she had a negative feeling when the staff implied that Anna fought to get her brother involuntarily admitted just to get rid of him.

Anna had thousands of questions but felt that the staff took up a defensive position toward her and her questions. For example, Anna describes how she repeatedly contacted her brother’s primary nurse and asked if she and her mother could meet with the physician in charge. Month after month went by and nothing happened. Finally, Anna contacted the physician in charge to book a meeting. The physician questioned the value and importance of such a meeting, but Anna insisted on it, telling him the questions she wanted him to answer. Finally, a date was decided on, and Anna thought she now would get the answers for which she had waited so long. She also looked forward to an information exchange. Satisfied and happy, Anna phoned the brother’s primary nurse to inform her about the upcoming arrangement. The response was unexpected; the nurse became angry and impertinent. Anna said, “So she asked me ··· or she said to me, ‘you can go to hell’ and then she threw down the receiver. ··· I thought, oh dear, what have I done wrong?” Anna thought that this behavior was unacceptable, and she was surprised and shocked.

In spite of the primary nurse’s reaction, Anna and her mother felt that the meeting was important and arrived expectantly at the ward at the appointed day and time, only to hear that the physician was not there. In the end, Anna learned that, after all, the physician was at the ward. So Anna and her mother, the primary nurse, the physician, and the chief nurse met at the ward office. Anna had written down her questions in a notepad, but the physiccian had only a small piece of paper with him and no information to give. The only answers she got to her questions were general and Anna felt that they all dismissed her questions by giving general answers. Anna was disappointed and angry and, as she said, “gave up” her efforts to get information.

According to Anna, this—providing only general information—was not the only way psychiatric staff tried to obstruct the relationship among Anna, her brother and the care. For example, if Anna phoned the ward she was not even allowed to know if her brother was there. “They hide behind secrecy.” According to Anna, her brother had never asked the staff to conceal to Anna his stay at the ward. Anna thought it was the staff themselves who made this decision. She said that her suspicion made her even more irritated with the staff.

Throughout the hospital stay, Anna asked about her brother’s diagnosis. She thought a diagnosis would simplify their search for information about her brother’s disease, his prognosis, and so on. In an earlier stage of her brother’s illness, Anna was informed that his condition was complicated. She was convinced that the psychiatric care was not capable of giving him a diagnosis, saying “it’s strange that they treat a person without knowing his diagnosis”. Anna said she believed a diagnosis would help her to act in an appropriate manner with her brother during her visits at the hospital ward. “The visits would have been so much more successful then.” Instead she would leave the hospital and her brother with an abiding feeling that the visits were unsuccessful.

3.3. Phase 3—The First Years in Forensic Psychiatry

Expectation of confirmation – contact with psychiatric care:

Anna said that the distrust between her and the psychiatry hospital was reciprocal; that is, she was suspicious and the staff distrusted the family. “There are many things that feel strange,” she said, explaining that she grew angry over the time that passed between the episodes when her brother was allowed leave the ward and go outside to be in the healthy air. “It took too long,” Anna experienced that those decisions, decisions about her brother’s supervised or non-supervised visits, were based on staff convenience, not her brother’s best interests. Therefore, it was not unusual that her brother’s condition did not improve, and Anna said that “she no longer had confidence in the staff or psychiatric care on the whole”.

Gifts that she sent to her brother seemed to have the tendency to disappear or be delivered to him long after she’d sent them, often after a reminder from Anna. The treatment she received during her ward visits was not professional. Staff would shout and swear, at her, at her brother, and at the patients in general. According to Anna, this showed their lack of interest in the patients’ wellbeing. The time her brother spent in a special unit within forensic psychiatry was also characterized by general information and general explanations from staff, something Anna did not like. She felt it was important that support, information, and explanations given should be based on the individual patient or family member. She also longed for a time when formal care would be interested in her personal knowledge of or experiences with her brother. “After all, I’m his sister.” Anna wanted to be a resource for her brother and she felt that all involved (his family and formal care) should have had the same expressed goals in his care and treatment.

Anna thought that if the formal care staff would meet with the family, an increased understanding would emerge and the family’s involvement would increase. Anna was also of the opinion that the physician who was responsible for her brother’s treatment did not have the correct information on which to base his treatment decisions. She said that it would be better if he met the patient instead of having his decisions grounded in information from others, usually ward staff and the primary nurse. Anna meant that family members who want to support an unhealthy relative must be given support from formal psychiatric caregivers. “It is extremely important how the staff behave, what the contact between the parties looks like. Staff could do a lot to help; they could arrange meetings and visits with the family—be the link that coordinates. We don’t want to hear just shit; we want to hear about our relative when he is well, also.” In addition, Anna meant that staff also had an obligation to help and cure broken relationships between the patient and the family, something the staff did not focus on at all.

3.4. Phase 4—Present Time within Forensic Psychiatry

Satisfaction of being confirmed – contact with psychiatric care:

Anna’s brother moved to a new ward and was assigned a new engaged and interested primary nurse as well as a new physician. When Anna visited her brother, the physician would spontaneously ask her if she had anything she wanted to discuss or ask him. She felt it was important that the doctor stayed at the ward. That way, he was able to create his own picture of the patient’s condition and his daily life at the ward instead of relying only on secondhand information from the staff. Anna participated in meetings at which her brother’s care was planned. She felt involved and felt that formal psychiatric caregivers listened to what she had to say. She felt that she was a real resource for her brother.

Anna was asked about her knowledge in matters that were relevant to her brother’s care and her advice was respected. The staff on the new ward did not hide behind secrecy, and Anna was given an opportunity to take part in the discussions about her brother. She had no information about her brother’s diagnosis, but thought that explanations given about her brother’s illness gave her satisfying knowledge; therefore, she felt the communication was good enough. The staff also kept her informed about her brother’s daily life at the ward, but she lacked information about his medication.

Anna said her desire is to help her brother lead a life “as normal as it can be”. She said that her dream is to coordinate a group of people to care for her brother in a homelike setting. Anna points out that she is not giving up; she is willing to keep struggling for the sake of her brother. When Anna was provided relevant information about her brother she believed she could give him better and more suitable help. Her opinions and suggestions are now taken under consideration by the staff. She now agrees with the actions taken to care for her brother. Anna says cooperation has now been established, a sense of cooperation for which she longed for many years. She does not believe her brother will ever have a “normal” life, though as “he has been hospitalized too long and destroyed by medical drugs”. Anna thinks she is now being given the opportunity to be a resource for her brother.

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this single case study was to illustrate, from a sister’s perspective, the experience of having a mentally ill brother and the relationship between family and formal psychiatric caregivers. The findings indicate the increasing needs that siblings have as family members in their relationship with the professional caregivers. It seems the possibility is high that this population, over time, will become involved in their relatives’ care either during hospitalization or, if the illness becomes longterm, as support in the community. Unfortunately, psychiatric care is extremely complex and difficult to access. To force one’s way in and to become an equal partner in an unhealthy sibling’s care is a challenge. It seems to take a persistent person to get what is needed from formal psychiatric care. In this case, Anna literally had to “scream” at formal care professionals that they not only needed to help her brother but also help his family.

The literature clearly reflects the ambivalence siblings experience in relation to themselves, their mentally ill relatives, and formal psychiatric caregivers. Anna was extremely motivated to help and support her brother in the best way she could. In the beginning she anxiously contacted psychiatric practitioners, begging them to help her brother. She had enough trust in the welfare system to ask for help. Although many family members see themselves “as the one who knows their relative best”, their influence on formal psychiatric care is limited and their responsibilities are limited by the law, formal care, or their relatives [27]. According to Sjöblom [9], the feeling of not being understood and listened to is a common among family members of the mentally ill. Anna’s experience is perhaps unique in that she did not give up her struggle with formal psychiatric care and strived to gain control over it.

According to the literature (e.g. [28,29]), the relationships between siblings are unique in that they are longlasting. Anna’s feelings of helplessness and frustration over not understanding her brother and not gaining understanding of him from the formal psychiatric caregivers seem to be overwhelming. The communication problem between Anna and the formal caregivers was an important barrier that came to characterize her future relationship with psychiatric care providers. Among others, Veltman [30], Doornbos [31], and Kaas et al. [32] state that defective information and support, together with formal caregivers’ nonchalant attitudes, indifference, and inaccessibility to family members, are frequent and important reasons that inhibit family members’ ability to become participants in their ill relative’s care.

The greatest tragedy for Anna, as for other siblings, was the dramatic change that her brother’s illness brought to her life situation along with feelings of isolation and helplessness, which she experienced as stressful. According to Barnable et al. [33], feelings of physical and psychological stress are common among siblings in relation to their sibling’s mental illness. For Anna and her family, the situation that led to her brother’s hospitalization was almost explosive; her brother did not understand he was ill and police assistance was ultimately required. The force the police used toward her brother was extremely stressful for Anna to watch. The importance of sensitive formal psychiatric care not only to the sufferer of a mental disease but also toward the sufferer’s family members becomes obvious when listening to Anna’s narrations. Providing early intervention services may be more cost effective and help to repel more serious relational problems between the two parties in the future (e.g., [34,35]).

It follows that inviting family members to actively participate in care helps to decrease the burden on a health care system that is already stretched to its limits. Therefore, identifying voluntary support as an important resource within mental health care may not only relieve the pressure on formal psychiatric care but also give siblings an opportunity to play an active part in their relative’s care [33]. The time has arrived to discard the elevated status of formal psychiatric care and allow siblings to play a more active part without being afraid their participation will have a negative effect. One was to do this is to significantly change the focus psychiatric nursing care from the traditional psychiatric perspective to a family member perspective [36]. However, it is important in this discussion to be aware of siblings’ situations and emotions regarding being a schizophrenic patient’s brother or sister [37].

It has been noted that siblings of people who suffer from schizophrenia are victim to many emotions in relation to this [e.g., 4]. Anger, sorrow, fear, and blame are common emotions reported [38,39]. In her narrations, Anna describes the self-blame she felt and the constantly present question, “Why him and not me?” This may explain her anger and the assertiveness she displays when she stands up for her brother against formal psychiatric care. According to Greenberg et al. [11] and Montero et al. [40], this is method of dealing with a sibling’s mental illness care is common among sisters. Feelings of guilt can be understood as a “basis” for other emotions and result in a situation in which the healthy sibling tries to compensate for the unhealthy sibling’s loss of a normal life through being his/her “voice and ambassador” [39]. Studies [41] have shown an increased awareness of genetic factors in schizophrenia. According to Titelman [38], siblings are interested in possible heredity and risk factors and show a fear of becoming mentally ill themselves. However, it is difficult to find studies investigating siblings’ perceptions and fears of their own possible schizophrenia susceptibility in the way that Anna articulates.

However, Anna’s wished involvement in her brother’s care was mostly on a practical level and did not involve her brother in the discussion. According to Kinsella et al. [42], it is a common coping strategy among siblings to use a “constructive escape”, that is, to distance oneself from the unhealthy sibling through focusing on practicalities. However, it seems as though there is a difference between siblings’ and parents’ roles and, according to the literature, siblings often emphasize that it is even harder to be a parent than a sibling to someone with schizophrenia (e.g., [43,44]). In Anna’s narrations, it is obvious that the affection she feels for her brother is strongly connected to her sorrow and that it can explain her satisfaction when formal care providers invite and allow her to cooperate with them as a resource person in her brother’s treatment. Lakeman [45] states that family members usually become more satisfied with their relative’s treatment if they are involved in it and feel that they are given current information about, for example, medication and mental state.

Clearly, more research is needed to determine if Anna’s story is a common one. If so, could mental health services be better prepared to meet the needs of siblings? By understanding the “normal” course of events and issues in psychiatric hospital settings, perhaps staff will have a better understanding of how to be more willing to cooperate with family members. Granted, more research is needed to determine if such an approach is oversimplified or right on target. Regardless of what path mental health care will take, the reality is that a course of action is needed to involve siblings in psychiatric care. Unfortunately, this is not new information—there are already studies that report on siblings’ emotional reactions and needs (e.g., [37,46])—but this single case study clearly reflects the struggle a sister must live through in contact with formal psychiatric care staff.

4.1. Conclusion

Even though this single case study focuses on only one individual’s experiences, the findings give an indication of siblings’ need for attention, support, and understanding from the health care system. For Anna, participation in our study was one of the first opportunities she had to talk about schizophrenia in the family and her relationship with formal psychiatric care. An open dialogue may help siblings manage their situations. One way could be to offer siblings participation in a professionally led grouprehabilitation program.

4.2. Methodological Considerations

In this single case study, our intention was to explore in a descriptive way a sister’s experience. The strategy was to search for meaning in the pattern that emerged [18]. A case study design is well-suited when the purpose of the research is to describe the holistic and meaningful aspects of real life events [21]. According to Stake [18, p. 8], “we take a particular case and come to know it well, not primarily as to how it is different from others but what it is, what it does. There is emphasis on uniqueness”.

It is important to keep in mind that ours is just one of many possible interpretations and that the present study is not an attempt to evaluate formal mental health care. Data are solely based on Anna’s personal experiences and are discussed strictly from a sibling perspective. It seems reasonable to assume that we may have reached a different interpretation had we used some other angle for understanding Anna’s unique story such as a staff or crisis perspective. Therefore, our intention is not to generalize our findings and interpretations but just to point at the complexity that lies in a sibling’s experience.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants who made this project possible.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, C., Reiss, D. and Hogarty, G. (1986) Schizophrenia and the family. Guilford, New York.

- Lefley, H. (1996) Family caregiving in mental illness. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Ferriter, M. and Huband, N. (2003) Experiences of parents with a son or daughter suffering from schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 10, 552-560. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00624.x

- Saunders, J.C. and Byrne, M.M. (2002) A thematic analysis of families living with schizophrenia. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 16, 217-223. doi:10.1053/apnu.2002.36234

- Sveinbjarnardottir, E. and Dierckx de Casterle, B. (1997) Mental illness in the family: An emotional experience. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 18, 45-56. doi:10.3109/01612849709006539

- Tuck, I., du Mont, P., Evans, G. and Shupe, J. (1997) The experience of caring for an adult child with schizophrenia. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 11, 118-125. doi:10.1016/S0883-9417(97)80034-9

- George, R.D. and Howell, C.C. (1996) Clients with schizophrenia and their caregivers’ perceptions of frequent psychiatric rehospitalizations. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 17, 573-583. doi:10.3109/01612849609006534

- Sjöblom, L.M., Peilert, A. and Asplund, K. (2005) Nurses’ view of family in psychiatric care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14, 562-569. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01087.x

- Sjöblom, L.M., Wiberg, L., Pejlert, A. and Asplund, K. (2008) How family members of a person suffering from mental illness experience psychiatric care. International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, 13, 1-13.

- Sjöblom, L.M., Hellzèn, O. and Lilja, L. (Submitted) Patients’ view of their families’ participation in psychiatric care—A qualitative interview study.

- Greenberg, J.S., Kim, H.W. and Greenley, J.R. (1997) Factors associated with subjective burden in siblings of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67, 231-241. doi:10.1037/h0080226

- Cicirelli, V.G. (1989) Feelings of attachment to siblings and well-being in later life. Psychology and Aging, 4, 211-216. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.4.2.211

- Campbell, L., Connidis, I. and Davies, L. (1999) Sibling ties in later life: A social network analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 114-118. doi:10.1177/019251399020001006

- Robinson, E. (1996) Causal attributions about mental illness: Relationship to family. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66, 282-294. doi:10.1037/h0080179

- Hatfield, A. and Lefley, H.P. (2005) Future involvement of siblings in the lives of persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 41, 327-338. doi:10.1007/s10597-005-5005-y

- Smith, M.J. and Greenberg, J.S. (2007) The effect of the quality of sibling relationships on the life situation of adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 58, 1222- 1224. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.58.9.1222

- Lincoln, Y. and Gruba, E.G. (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications, Newbury Park.

- Stake, R.E. (1995) The art of case study research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Hamel, J., Dufour, S. and Fortin, D. (1993) Case study methods. Sage Publications, Newbury Park.

- Beeman, S. (1995) Maximizing credibility and accountability in qualitative data collection and data analysis: A social work research case example. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 22, 99-114.

- Yin, R.K. (2003) Case study research: Design and methods. 3rd Edition, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Sandelowski, M. (1994) We are the stories we tell: Narrative knowing in nursing practice. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 12, 23-33. doi:10.1177/089801019401200105

- Patton, M.Q. (2002) Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 3rd Edition, Sage Publications, Newbury Park.

- Graneheim, U.H. and Lundman, B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105-112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Polit, D.F. and Beck, C.T. (2004) Nursing research, principles and methods. 7th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

- King, G.A., Cathers, T., Polgar, J.M., MacKinnon, E. and Havens, S. (2000) Success in life for older adolescents with cerebral palsy. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 734- 749. doi:10.1177/104973200129118796

- Milliken, P.J. and Northcott, H.C. (2003) Redefining parental identity: Caregiving and schizophrenia. Qualitative Health Research, 13, 100-113. doi:10.1177/1049732302239413

- Lamb, M.E. and Sutton-Smith, B. (1982) Sibling relationships: Their nature and significance across the life span. Erlbaum, Hillside.

- Stålberg, G., Ekerwald, H. and Hultman, C.M. (2004) At issue: Siblings of patients with schizophrenia: Sibling bond, coping patterns, and fear of possible schizophrenia heredity. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 30, 445-458. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007091

- Veltman, A., Cameron, J. and Stewart, D.E. (2002) The experience of providing care to relatives with chronic mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190, 108-114. doi:10.1097/00005053-200202000-00008

- Doornbos, M.M. (2002) Family caregivers and the mental health care system: Reality and dreams. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 16, 39-46. doi:10.1053/apnu.2002.30541

- Kaas, M.J., Lee, S. and Peitzman, C. (2003) Barriers to collaboration between mental health professionals and families in the care of persons with serious mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 24, 741-756.

- Barnable, A., Gaudine, A., Bennett, L. and Meadus, R. (2006) Having a sibling with schizophrenia: A phenomenological study. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 20, 247-264. doi:10.1891/rtnp.20.3.247

- Häfner, H., Maurer, K., Ruhrmann, S., Bechdolf, A., Klosterkötter, J., Wagner, M., Maier, W., Bottlender, R., Möller, H.J., Gaebel, W. and Wölwer, W. (2004) Early detection and secondary prevention of psychosis: Facts and visions. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 254, 117-128. doi:10.1007/s00406-004-0508-z

- Addington, D. (2009) Best practices: Improving quality of care for patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 60, 1164-1166. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.9.1164

- Piippo, J. and Aaltonen, J. (2008) Mental health care: Trust and mistrust in different caring contexts. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 2867-2874. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02270.x

- Nechmad, A., Fenning, S., Ternochiano, S., Treves, I., Fennig-Naisberg, S. and Levkovich, S. (2000) Siblings of schizophrenic patients—A review. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 37, 3-11.

- Titelman, D. (1991) Grief, guilt and identification in siblings of schizophrenic individuals. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 55, 72-84.

- Syrèn, S. (2010) Det outsagda och ohörsammade lidandet. Tillvaron för personer med långvarig psykossjukdom och deras närstående (in Swedish). Doktorsavhandling, Linnaeus University Dissertation Nr 6/2010. Linnaeus University Press, Småland.

- Montero, I., Hernandez, I., Asencio, A., Bellver, F., LaCruz, M. and Masanet, M.J. (2005) Do all people with schizophrenia receive the same benefit from different family intervention programs? Psychiatric Research, 133, 187-195. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2002.12.001

- Cardno, A.G., Rijsdijk, F.V., Sham, P.C., Murray, R.M. and McGuffin, P.A. (2002) Twin study of genetic relationships between psychotic symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 539-545. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.539

- Kinsella, K.B., Anderson, R.A. and Anderson, W.T. (1996) Coping skills, strengths, and needs as perceived by adult offspring and siblings of people with mental illness: A retrospective study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 20, 24-32.

- Stein, C.H. and Wemmerus, V.A. (2001) Searching for a normal life: Personal accounts of adults with schizophrenia, their parents and well-siblings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 725-746. doi:10.1023/A:1010465117848

- Muhlbauer, S.A. (2002) Navigating the storm of mental illness: Phases in the family’s journey. Qualitative Health Research, 12, 1076-1092. doi:10.1177/104973202129120458

- Lakeman, R. (2008) Family and carer participation in mental health care: Perspectives of consumers and carers in hospital and home care settings. Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 15, 203-211. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01213.x

- Teschinsky, U. (2000) Living with schizophrenia: The family illness experience. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 21, 387-396. doi:10.1080/016128400248004