Health

Vol.5 No.3A(2013), Article ID:29600,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.53A076

Personal recovery and involuntary mental health admissions: The importance of control, relationships and hope*

![]()

1University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; #Corresponding Author: m.wyder@uq.edu.au

2Queensland Health, Brisbane, Australia

Received 10 January 2013; revised 14 February 2013; accepted 24 February 2013

Keywords: Mental Health; Recovery Framework; Users’ Experiences; Involuntary Treatment

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Involuntary mental health admissions remain a highly contested area in law, policy and practice. There are growing concerns about the effectiveness and potential harms of using coercion to enable treatment. These concerns are heightened by the worldwide shift to recovery oriented care, which emphasizes the importance for mental health consumers experiencing selfsufficiency, control and having input into their own treatment. Involuntary treatment challenges these very principles. Methods: For this study we adapted Noblit and Hare Meta Ethnography methods and synthesized the themes of seven qualitative studies which focused on the experiences of involuntary mental health admission. Results: Seven overarching dimensions were identified as either hindering or facilitating recovery, namely: 1) having input into own treatment; 2) shared humanity; 3) power imbalance/ balance; 4) freedom and control; 5) ability/inability to incorporate the episode/experience; 6) treatment factors; and 7) importance of relationships. Conclusions: The findings of this study indicate that the recovery framework, in particular the concepts of hope, relationships and control are very relevant in the context of involuntary settings.

1. INTRODUCTION

Serious mental illness can be profoundly life changing for those experiencing the symptoms. Even though people recover from a mental illness, others experience years of distressing symptoms, disability and many knock on effects of the illness such as homelessness, poverty, and unemployment [1]. Many may also experience involuntary mental health admissions. These experiences range from being subjected to a Community Treatment Order to an involuntary mental health admission, with or without the administration of measures such as seclusion, restraint and forced medication [2]. Involuntary treatment remains a highly contested area in law, policy and practice with many tensions among the different parties involved [3]. Even though these interventions might be done with the best interest of the patients at heart, there are growing concerns about the effectiveness and the potential harms of using coercion to enable treatment [4]. These concerns are heightened by the worldwide shift to recovery oriented care, which emphasizes the importance for mental health consumers to experience self-sufficiency, self-advocacy, control and empowerment as well as having input into their own treatment. Involuntary treatment challenges the very principles of recovery based care and mandatory treatment would appear to be incompatible with the recovery framework.

Recovery, defined simply as the ability to live well in the presence or absence of one’s mental health symptoms [5], is now central to mental health care policy and delivery in Australia and internationally [3,6,7]. Recovery is generally viewed as a process or a journey, in which the individual finds meaning and build a life beyond their illness. During this journey a person takes more responsibility over their illness, gains a sense of control over their life as well as gaining hope for the possibility of a better future. Many users (clients) of mental health services refer to themselves as consumers, as it signifies that they have the power to choose services and treatment most suitable to their needs.

Recovery is not necessarily a linear journey and many consumers will experience setbacks. The recovery framework places the consumer at the heart of the experience and focuses on the following nine elements: 1) renewing hope and commitment; 2) redefining self; 3) incorporating illness; 4) being involved in meaningful activities; 5) overcoming stigma; 6) assuming control; 7) becoming empowered and exercising citizenship; 8) managing symptoms; and 9) being supported by others [5]. In addition recovery can only occur when external conditions such as human rights, a positive culture of healing, and recovery oriented services are present [8]. The National Standards for Mental Health Services emphasize that mental health services provide consumers with the opportunities and choices and provide them with the support to live a meaningful, satisfying and purposeful life (as they would define this). Their role is to ensure that individuals are at the center of the care they receive. The guidelines also emphasize the need for services to promote and protect the individual’s citizenship and their legal and human rights [9].

The contradictions between recovery, recovery oriented care and involuntary treatment are particularly apparent for involuntary hospital admissions. For many people, an involuntary mental health admission represents not only the culmination of acutely distressing symptoms of illness, but also the unwelcome experience of being confined to hospital and experiencing the imposition of treatments/restrictions. Restrictions include not being allowed to leave or to be discharged from the ward, being confined to one’s room, mechanical restraint, and forced medication, all of which can be experienced as invasive and distressing. For some these experiences, even the less invasive ones, can have a negative impact on the recovery journey [4]. Conversely, an involuntary hospital admission can also be a turning point and represent the best hope of getting well enough for recovery to be possible [10].

Little is known about the factors that influence these experiences. It is possible that those who are treated involuntarily, when compared with those treated voluntarily, have more chronic mental health issues, have less social support, experience worse illness related symptoms and describe lower social functioning when entering the service and at time of discharge [2]. It is has been suggested that people who experience more severe symptoms, are more likely to be non-cooperative and are at greater danger to themselves and others and therefore are more likely to experience an involuntary mental health admission. However, it is also possible that certain aspects of coercive treatment might be harmful and influence some of these factors [2,4]. Quantitative studies have failed to show any difference between voluntary and involuntary patients in terms of improvement while in care, treatment and medication compliance once discharged [2]. In contrast some qualitative studies have highlighted that involuntary inpatients were more likely to report a subjective lack of improvement, to voice more negative experiences in hospital and to view their care in a more negative way when compared to voluntary patients [2,4,11]. This would suggest that the actual involuntary nature of the treatments could have a negative impact on the recovery journey and that this experience is not captured by the quantitative literature.

Little is known about the relevance of the recovery framework in the context of involuntary mental health admissions. While there is some research into involuntary mental health admissions, there is very limited research investigating the role of recovery theory in involuntary settings. Given the importance of recovery oriented care and the potentially serious implications involuntary treatments can have on a person’s recovery journey, this lack of understanding is of great concern. Similarly, there is also limited knowledge on how to apply recovery oriented principles to involuntary mental health admissions. In order to achieve the best outcomes for those treated under the mental health act, it is imperative to translate the recovery philosophy into clinical care principles. This information would contribute not only to the developments of treatments that are more grounded in the experiences and needs of consumers but would also inform ways in which mental health workers can maximize the recovery process during involuntary hospital admission. In this article we investigate the relevance of the recovery framework to the experience of an involuntary mental health admission.

2. METHODS

For this study we used an adapted version of the metaethnography developed by Noblit and Hare [12]. This methodology aims to bring together the findings of different qualitative studies around a chosen theme. This comparative approach involves the systematic compareson of study findings and the translation of each into the other (one case is like another, except that). We followed the steps developed by Noblit and Hare [12]. First we identified our topic and the relevant studies. We then read all the studies and determined the relationship among them. In a meta-ethnography the themes are then reanalyzed. As we were interested in how different themes related to the recovery framework, instead of reanalyzing the original data, we focused on the impact of the involuntary mental health admission on the person. An involuntary mental health admission could have a profound negative or positive impact on a person and different factors/themes were identified as contributing to these experiences. These themes were summarized. A framework analysis was performed on these themes and identified seven overarching themes. These themes provide a descriptive framework of the available literature on the qualitative experiences of an involuntary mental health admission and highlight important factors that influenced a person’s recovery during an involuntary mental health admission and how these might relate to the recovery framework.

3. THE SAMPLE

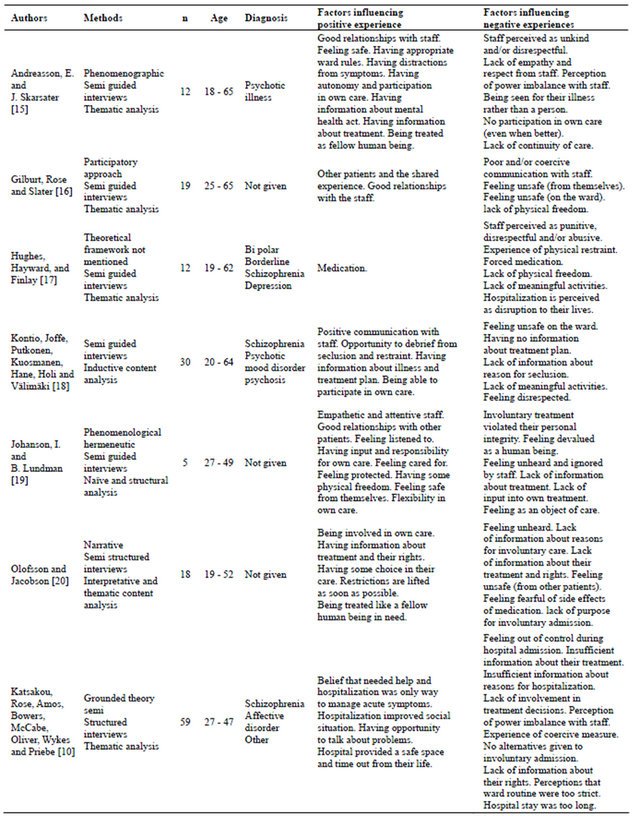

For this synthesis we focused on the qualitative, subjective experiences of those who had experienced an involuntary mental health admission. The legislation on involuntary treatment has substantially changed during the past 15 years. To keep the findings relevant to today’s legislative context we have only included qualitative articles published in the past 15 years. Psychinfo, Medline, Cinahl, Scopus and Web of Science were searched with the following search strategy: Involunt/* OR Compulso/* OR Coerc/* AND Mental/* OR Admission/* OR Detention/* OR Commit/* OR treatment AND Qualitative. We retrieved 355 articles from Psychinfo; 127 form Cinahl; 109 from Scopus and 149 from Web of Science; and 22 from Medline. The titles and abstracts were scanned and articles that focused the experience of involuntary mental health admission were included. The reference lists of relevant articles were also scanned. A total of 17 articles reported on the experiences of involuntary inpatient. Only those that reported on the experiences of an involuntary mental health admission were included. We excluded ten articles for the following reasons: Not published in a peer reviewed journal (n = 2); no differentiation made between the experiences of voluntary and involuntary patients (n = 2); focus on coercive events/seclusion (n = 4); review articles (n = 2). This brought the sample down to seven articles. Even though there were differences in the theoretical frameworks used, all studies focused on the lived experiences of people who had experienced an involuntary mental health admission and developed their codes inductively. In Table 1 we summarize the different methods and approached used.

4. RESULTS

Despite the different qualitative frameworks used, and some differences in age and diagnosis, the lived experiences of involuntary mental health admissions were described in similar terms. An involuntary mental health admission has a profound emotional impact on participants. Those who described the admission as a more positive experience felt that it had allowed them to feel empowered and valued, it also helped them adjust to their mental illness. Those who described the experience in more negative terms felt that the involuntary mental health admission had left them feeling violated, punished, disrespected, ignored, invisible and unacknowledged as a human being. Each study identified different subthemes that influenced these feelings. These subthemes are presented in Table 1.

We identified seven overarching themes. These were: 1) having input into own treatment; 2) shared humanity; 3) power imbalance/balance; 4) freedom and control; 5) ability/inability to incorporate the episode/experience and safety aspects; 6) treatment factors; and 7) importance of relationships. Within each of these dimensions the participants described a range of experiences, some of which appeared to hinder while others facilitated recovery. Table 1 provides the details as to where these themes were reported.

Theme 1: Having input into own treatment Consumers talked about the importance of having some input into their own treatment. Some felt that they were not given any consideration or opportunity to be involved in their own care, nor were given any alternatives to involuntary care. Others felt that they were kept on the treatment order for too long. These issues left them feeling unheard, misunderstood, devalued and ignored. They also felt that their rights were taken away. However, when consumers had the possibility to maintain some autonomy and freedoms, even if these were very small, were given some room for autonomous decisions and participation in their own care, in particular when they started to feel better, they felt empowered, heard and valued. Being allowed input and being given the opportunity to contest their involuntary treatment order (even if the outcome is not what they desired) gave them a sense of procedural justice. When these opportunities were present, many consumers found it easier to adjust to and accept the need for compulsory treatment.

Theme 2: Shared humanity For many consumers involuntary treatment was experienced as a violation of their personal integrity and a loss of basic human rights. Consumers in this group felt that they were not treated like human beings. Having their rights taken away was experienced as a violation of their personal integrity. Many felt that the experience had left them invisible, feeling like an animal or criminal, as an object of care without the same human value as a healthy person. On the other hand those who felt they were treated as somebody that could be counted on, or as a fellow human being in need and were allowed to be involved in meaningful activities, felt respected and that the experience allowed them to gain self-confidence.

Theme 3: Power imbalance/balance Some consumers felt that there was a strong power imbalance while they were receiving involuntary care. This power imbalance was the result of: 1) not receiving appropriate information about their Involuntary Treatment Order. This could either be too much information too soon or not enough information about their treatment;

Table 1. Methods, demographic characteristics and dimensions influencing positive or negative experiences of an involuntary mental health admission.

2) inadequate or no information about their legal rights/ status and the reasons for their hospitalization; and 3) not being given information about alternative treatment options. Many also perceived some staff as abusing their power, unkind and disrespectful. This power imbalance led consumers to feel punished, violated, abused and helpless. Conversely, consumers who felt that they had appropriate information about the compulsory treatment, knowledge about their rights, up to date information about their treatment plans, and information about why they needed involuntary care, felt more empowered and described that this had helped to facilitate their healing.

Theme 4: Freedom and control Some consumers experienced the loss of freedom acutely. Having no autonomy, with strict and inflexible ward regimes, no outside spaces and not being able to leave made them feel powerless. At times this loss of freedom translated into a feeling that they had lost control over their lives. On the other hand, consumers who felt that they were moved toward freedom as soon as possible (i.e., being able to go home for a few hours, having permission to leave the ward or being able to meet with family and friends) and had some flexibility in their care and perceived the ward rules as reasonable, felt empowered. Many also felt that the ward rules made them feel secure as it meant that they were treated with firmness and were given limits.

Theme 5: Ability/inability to incorporate the episode/ experience For some the involuntary treatment was experienced as an unnecessary disruption to their lives and others feared that the mental health system would impact on their lives permanently. The involuntary treatment was perceived as a constant threat to their efforts to live independently. These fears often led to feelings of hopelessness and pessimism about the future. In contrast to this, for others the involuntary treatment was an opportunity to have time out and recover from their illness and might even have improved their social situation (e.g., housing and finances). It provided them with the opportunity to talk to professionals about their problems. Patients also noted the importance of having the opportunity to have frequent talks, the importance of ordinary conversation and practical support. Similarly, it was important to have the opportunity to debrief and reflect on their experiences of compulsory treatment and coercive interventions. This self-reflective time led to their being able to incorporate their illness, to develop insight and as well as how future compulsory treatment could be prevented or made easier.

Theme 6: Treatment factors For many the involuntary treatment was experienced as meaningless with a sole focus on medication and the importance of the side effects of the medication. They felt that the stay in hospital was only a form of storage, where nothing happened. They did not believe that they had the opportunity to talk or receive psychotherapy. Some described the experience as hindering their healing as they felt worried about the side effects of medications and that medication would alter who they are. Those who felt that they were engaged in meaningful activities and were offered alternative treatment to medication and/or for whom the medications was helpful, not surprisingly felt that these were a crucial part in their healing.

Theme 7: Importance of relationships Relationships with other patients and staff were identified as being the most important factor that can either facilitate or hinder the healing process. For example, interactions with other patients can help build a shared experience and increase their confidence. Conversely, feeling unsafe on the wards because of violence (either by themselves or other consumers) can make them feel more insecure. Communications with family and friends were also identified as important.

The most important relationships while they were in hospital however were those with staff. When staff was described as distant, not caring, with poor communication skills, were perceived as incompetent and/or did not have not time to listen or talk, this hindered the healing process. In contrast healing occurred when staff was perceived as competent, trustworthy, reliable, attentive, showed concern and were interested in patient progress and having time. This was particularly important when patients experienced seclusion/restraint. These relationships helped alleviate patients’ feelings of fear and uncertainty, and helped them feel more secure and supported as well as cared for. It also made it easier to accept and justify the involuntary treatment.

In summary, the factors identified with more positive experiences during an involuntary treatment included being seen and treated as a fellow human being (shared humanity), being respected and heard, having had the opportunity to incorporate the illness, having a safe place in which they can recover from their episode, having a balanced relationship with the health care professionals, being able to experience a return to freedom and flexibility, as well as having the opportunity to have some type of input into their own treatment. In addition, consumers felt that this was more likely to happen when the treatment they received was perceived as useful and meaningful and if they had positive relationships with their health care professionals. It was particularly important to them that health care professionals had the ability not only to hold but also to return control.

Conversely, those who had more negative experiences often described feeling unsafe on the ward, were unable to make sense of the episode (including feeling hopeless), experienced a strong power imbalance with the health care professionals, felt that they had no say in their own care or treatment, experienced a loss of humanity and a loss of control and power to decide for themselves. They also felt that these experiences were influenced by the perception that they received treatment that was useless at best and harmful at worst, and their negative relationships with staff that were experienced as punitive and powerful and had no interest in their well-being.

5. LIMITATIONS

While the research used as a basis for this study identified clear themes (positive and negative) around the experiences of an involuntary mental health admission, with the exception of Katsakou et al. [10], none of the articles indicated whether there were differences among the participants based on diagnosis, severity of the illness, length of illness and/or the stages of their recovery. It is unclear if where a person is at in their recovery journey may have influenced the way they experienced their involuntary mental health admission. Further research is needed to explore these potential differences.

6. DISCUSSION

As a group, people who have experience an involuntary mental health admission often experience worse illness related symptoms and are at greater danger to themselves [2] and it is often argued that it is a person’s diagnosis rather than the actual involuntary treatment, that influences their perceptions of involuntary care. In this synthesis we highlight that aspects of the involuntary experience could have a profound impact on their wellbeing. Furthermore, we highlight the importance of applying recovery principles to involuntary treatment. People who experience an involuntary mental health admission clearly express the need to be treated as a fellow human being, to have input into their treatment and to have control over their lives and illness returned to them as soon as possible. Despite the clear challenges that an involuntary treatment poses to these principles many also experienced the involuntary mental health admission as an opportunity to facilitate the renewal of hope, to redefine themselves and to incorporate and manage the illness.

Power and control At the heart of involuntary treatment is the restriction of personal freedoms, coercion of treatment, and denial of autonomy. Decisions about one’s body are made by others. Control is also a central tenant of the recovery framework. It is an irony that the ability to maintain some control, to feel empowered and to have some input into one’s own treatment is so central in the context of an involuntary mental health admission where consumers have so little control. It appears possible for some consumers to maintain a subjective sense of control even when objectively all control has been taken away. Many of the studies in this review identified ways in which treatment staff might work with consumers to mitigate the worst effects of loss of power and control. The most important were treating consumers with respect, giving appropriate information about their treatment and hospital admission, allowing whatever choice was possible within clear and defined boundaries, being invited to participate as much as possible in their own care as well as encouraging consumers to continue to have input in treatment decisions. Furthermore, knowing and being informed of ones rights, being involved and using the legal avenues (such as the mental health review tribunal) and having been given information about their treatment can also foster this internal sense of control. This shows that the concept of control can be seen as a gradual concept with many different layers. The health care professsionals’ ability to hold control as well as gradually giving back this control also appears central in fostering this subjective sense of control. It is another contradiction that part of the therapeutic aspect of the involuntary treatment order is about being given control back rather than taking away control. In this sense the goal of the order appear to become “getting off” rather than “being on” the order.

One important implication of this would be for treatment staff to start conceptualizing their work not so much as containing and/or controlling risky behaviors, but as a using temporary coercion to restore power and agency that has been lost through the illness and the need to intervene. The role of staff would be to provide support and containment at a difficult stage of a longer recovery process. If the episode is viewed as a temporary setback, then an overall focus of recovery principles can be maintained.

It is also important to note that some patients might be so ill and disordered in their thinking that they will inevitably experience all staff activity, no matter how caring and careful, as intrusive, coercive and unwelcome [13]. Given the nature of serious mental illness, such conflicts of perceptions will sometimes happen, but they are not inevitable and do not negate the basic principle of the staff’s obligation to support the patient’s sense of power, control and agency.

A focus on relationships The importance of supporting respectful relationships between the consumer and their network/relationships was a consistent finding. Most of studies emphasized the importance of good relationships between the patient and the treatment staff. Again this is a core tenant of the recovery framework. This finding is significant both theoretically and practically. In the first instance it suggests the importance of sustaining the relationship dimensions of recovery at a time when the rights, freedoms and agency are most compromised. It also emphasizes the need for mental health workers to see their role as forming sustaining relationships with the consumer, and in helping family and friends to continue to provide support during the time of involuntary treatment. This is skillful work requiring a change of therapeutic focus for staff that will need to move away from simply containing the patient, to working closely with families and friends to continue to support and sustain the patient.

There is a consensus that involuntary mental health admissions are necessary under certain circumstances and that minimizing the use of involuntary treatment is desirable, however, there is little agreement about how this should be done in practice [3]. The challenge for mental health workers and families is to find ways in which mental health consumers, who might be temporarily unable to be self directing in their treatment, can retain a maximum level of autonomy within the limits of involuntary care [14]. In this analysis we have emphasized the need to locate the episode of involuntary treatment within a broader recovery journey that might have different meanings for individuals. There is a wide variety of experiences of an involuntary mental health admission and mental health workers need to be mindful this and be prepared to encourage patients to see the positive, recovery affirming aspects this experience.

In this review we suggest some ways mental health workers can maximize important aspects of the recovery process (such as the opportunities for sustaining hope, for promoting agency, for supporting relationships and for redefining self) within the involuntary treatment. The impact of the mental health admission on the long term recovery still remains unclear The use of involuntary treatment has been one of the most contentious legal provisions in psychiatry. And while there is now a mounting body of research into this area there is currently limited evidence about the effectiveness and its impact on a person’s recovery [4]. This is an issue that needs to be addressed.

REFERENCES

- Morgan, V., Waterreus, A., Jablensky, A., Mackinnon, A., McGrath, J., Carr, V., Bush, R., Castle, D., Cohen, M., Harvey, C., Galletly, C., Stain, H., Neil, A., McGorry, P., Hocking, B. and Shah, S. (2010) People living with psychotic illness. Report on the 2nd Australian National Survey, Commonwealth Department of Health & Aging, Canberra.

- Kallert, T.W., Glöckner, M. and Schutzwohl, M. (2008) Involuntary vs. voluntary hospital admission. A systematic literature review on outcome diversity. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 258, 195- 209. doi:10.1007/s00406-007-0777-4

- Bland, R., Renouf, N. and Tullgren, A. (2009) Social work practice in mental health. Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

- Churchill, R., Owen, G., Singh, S. and Hotopf, M. (2007) International experiences of using community treatment orders. Department of Health, London.

- Davidson, L., O’Connell, M., Tondora, J. and Lawless, M. (2005) Recovery in serious mental illness: A new wine or just a new bottle? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36, 450-487.

- Jacobson, N. and Curtis, L. (2000) Recovery policy in mental health services: Strategies. States Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 23, 333-341.

- Meadows, G., Singh, B. and Grigg, M. (2007) Mental health in Australia. Melbourne. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Jacobson, N. and Greenley, D. (2001) What is recovery? A conceptual model and explanation. Psychiatric Services, 52, 482-485.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2010) National standards for mental health. Canberra, Australian Government.

- Katsakou, C., Rose, D., Amos, T., Bowers, T., McCabe, R., Oliver, D., Wykes, T. and Priebe, S. (2012) Psychiatric patients’ views on why their involuntary hospitalisation was right or wrong: A qualitative study. Social PsyChiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 1169-1179. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0427-z

- Bonsack, C. and Borgeat, F. (2005) Perceived coercion and need for hospitalization related to psychiatric admission. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 28, 342-347.

- Noblit, G. and Hare, D. (1988) Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Sage Publications, London.

- Olofsson, B. and Norberg, A. (2000) Experiences of coercion in psychiatric care as narrated by patients, nurses and physicians. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33, 89-97. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01641.x

- Bland, R. and Epstein, M. (2008) Encouraging principles of consumer participation and partnership: The way forward in mental health practice in Australia. In: Taylor, S. Foster, M. and Fleming, F.J., Eds., Health Care Practice in Australia, Allen and Unwin, South Melbourne, 239- 254

- Andreasson, E. and Skarsater, J. (2012) Patients treated for psychosis and their perceptions of care in compulsory treatment: Basis for an action plan. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19, 15-22. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01748.x

- Gilburt, H., Rose, D. and Slade, M. (2008) The importance of relationship in mental health care: A qualitative study of service users’ experiences of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Service Research, 8, 92-104. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-92

- Hughes, R., Hayward, M. and Finlay, W. (2009) Patients’ perceptions of the impact of involuntary inpatient care on self, relationships and recovery. Journal of Mental Health, 18, 152-160. doi:10.1080/09638230802053326

- Kontio, R., Joffe, G., Putkonen, H., Kuosmanen, L., Hane, K., Holi, M. and Välimäki, M. (2012) Seclusion and restraint in psychiatry: Patients experiences and practical suggestions on how to improve practice and use alternatives. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 48, 16-24. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00301.x

- Johanson, I. and Lundman, B. (2002) Patients’ experiences of involuntary psychiatric care: Good opportunities and great losses. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 9, 639-647. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00547.x

- Olofsson, B. and Jacobson, L. (2001) A plea for respect: Involuntary hospitalized psychiatric patients’ narratives about being subjected to coercion. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 8, 357-366. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.00404.x

NOTES

*We have no conflict of interest (or potential conflict) of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.