Food and Nutrition Sciences

Vol. 4 No. 10 (2013) , Article ID: 36984 , 6 pages DOI:10.4236/fns.2013.410137

Innovative Food Safety Strategies in a Pioneering Hotel

![]()

Department of Leisure Management, Yu Da University, Miaoli County, Chinese Taipei.

Email: sw520@ydu.edu.tw

Copyright © 2013 Su-Ling Wu. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received June 28th, 2013; revised July 28th, 2013; accepted August 5th, 2013

Keywords: Food Safety Strategies; Food Safety Control System (FSCS); Hotel

ABSTRACT

A case study approach was adopted to identify the innovative food safety strategies in place at one pioneering hotel that had voluntarily implemented food safety control. An investigation of food safety strategies and the reasons for their implementation in the hotel foodservice were carried out using multiple sources of data, including interviews with key decision makers in the hotel, observations of the business environment, and a review of documentation. The findings suggest that not only food control strategies but also marketing and corporate strategies are important when addressing the problems of food safety. The findings of this study also demonstrate the relationship between motivating factors and food safety strategies. Analysis of the interviews indicates that a hotel’s food safety strategies depend significantly on the attitude of senior management, the firm’s capability, and corporate image.

1. Introduction

Despite the advances in technology and hygiene standards in the past three decades, the outbreaks of fatal food born illness continued to increase globally, such as outbreaks of Salmonella serotype Enteritidis (SE), Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) and Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) in Europe and Northern America; Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Japan; cholera in Asia, Africa, and Latin America [1]. Life style changes and rapid global economic growth contributed to this trend [1]. These two factors lead to great numbers of people eating processed or imported food, and consuming food in foodservice establishments; and the increase of global movement in food supply and people also increase the exposure rate of contacting food born illness due to the unawareness of food born hazard on imported food or on food consumption while traveling aboard [1]. To help curb the rate of food born illness generated by the food industry, government agencies in Taiwan and other countries continue to pass new regulations, such as mandatory or voluntary enforcements of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), Good Hygienic Practices (GHP), Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) and ISO 9000 and 22000 series. Moreover, other stakeholders, such as food safety advocacy groups, customers, the press and media, and others, are pushing for firms to take food safety strategies from farm-to-fork, such as risk assessments throughout the external supply chains and the internal production process proactively into their managerial decision making process to minimize contamination which lead to loss of reputation, revenue, and even disruption of business. The incidence of food borne illness may damage the reputation of a country as a tourist destination [2]. The dining experiences of tourists were among the most important predictors of overall travel satisfaction [3,4]. Other researches indicated that the perception of food risks at their travel destinations also influenced their purchasing decisions for other products, especially when they were traveling to less developed countries [5,6]. Therefore, implementation of a certified food safety standard such as the GHP and HACCP standards would benefit especially less developed countries or regions, like Taiwan, by offering food quality assurance, strengthening the foodservices’ competitiveness and ultimately enhance the country or region’s reputation as tourist destination. In Taiwan approximately 40% of food borne illness outbreaks was linked to commercial food establishments (http://www. fda.gov.tw). Due to these repeated outbreaks of food borne illness, the Taiwanese Health Department in 2000 published a Food Safety Control System (FSCS), which includes principles from both HACCP and Good Hygienic Practice (GHP), in order to bring Taiwan in line with international standards. Beginning in September 2008, the Taiwanese Heath Department has been promoting the FSCS standards with stringent guidelines for the hotel industry. These standards have been gradually taking effect in outlets with central kitchens or kitchens in international tourist hotels. In order to promote the Taiwanese tourism industry, since 2009 the Taiwan Tourism Bureau has provided financial incentives to encourage the hotel industry to improve their facilities and service quality to meet international standards by obtaining local or internationally recognized certificates such as FSCS (http://admin.taiwan.net.tw).

Consumers react strongly to negative reports of food safety and their purchasing behaviors are negatively influenced [7]. Consumer food safety concerns have increased rapidly in recent years, as several high profile food incidents grabbed the head lines. Nevertheless serious incidents continue to occur. Food safety concerns have become an important factor for consumers in determining food selection and consumption. Chemical food additives, meats from diseased pigs and pesticide residuals are considered to be the most severe food safety problems by consumer in Taiwan, especially while they dine in commercial food outlets and consume processed food or meat products [8]. Similar results were also found in two studies which indicated that food safety issues influenced consumers’ dining-out decisions [9,10]. Fears of being featured on the media and press were one of reasons for foodservice initiating food safety control program [11]. Therefore, the foodservice industry should try to build their reputation by offering less pre-packaged, processed food and more on healthy, nutritious fresh certified produces. Food Safety Control System (FSCS) specifies the requirements needed for food safety management to ensure the final food is safe for consumption. Therefore, the innovative food safety strategies currently adopted and the strategies being carried out in a pioneering hotel are the focus of this study.

Previous hospitality food safety research has focused only on the food safety control strategy. However, that the levels and types of food safety control strategy include not only a functional strategy (control and marketing strategy), but also a business (competitive advantage) and a corporate strategy (a link with quality and other corporate objectives) [12,13]. The main aim of this study was to understand the food safety strategies (activities) in a hotel food service, while government bureaus have been gradually putting requirements and standards in place, and encouraging tourist hotels to gain FSCS certification. This study explores experiences of the implementation and operation of FSCS in a pioneering international tourist hotel in Taiwan, and thus identifies the key motivating factors and the challenges to implementing food safety strategies.

2. Method

An investigation of food safety strategies and the reasons food safety strategies are or are not implemented in hotel food services was carried out using multiple sources of data, including interviews, observation of environmental conditions, and the review of documentation to increase the construct validity and reliability of this study [14]. The method was designed to yield results that would assist the prediction of future drivers of food safety strategies and their uptake in the hotel food service industry. A franchised international tourist hotel that had voluntarily implemented the Food Safety Control System (FSCS) was identified as a suitable participant for the purposes of the study.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with senior management in the hotel, such as managers, chefs, and food safety supervisors, who were in management teams that had received special training in food safety control system principles [13]. The interviewer (the researcher) specifically directed open-ended questions to the interviewee in relation to food safety strategies. A set of questions was as follows:

1) What are the food safety practices in your company? How are they carried out in your firm? Why?

2) Is it convenient for you to practice food safety strategies? If not, how could it be made convenient for you?

3) What is your biggest food safety management difficulty?

4) Is there anything that would assist you in your food safety management efforts?

With the consent of the participants, interviews were taped and later transcribed. A pattern matching analytical procedure was used to increase the internal validity of a study [14]. It was anticipated that this analysis would lead to a set of food safety strategies being identified and their motivators.

The case study was conducted in a hotel that was a locally owned franchise of an international hotel chain. The chain’s first hotel opened in the early 1990s in Taiwan and there are now 9 hotels in the chain. The company has been striving to reinforce food safety strategies voluntary since early 1999 in all its hotels. It is company policy that all hotels in the chain adopt a food safety control system (FSCS). The hotel that participated in this study obtained FSCS certification in 2011.

3. Results and Discussion

Seven interviews with staff from the chain hotel were conducted for the case study. The interviewees included managers in the food and beverage departments, executive chefs, food safety supervisors, personnel managers and general managers. Most had been in the hotel industry for more than 10 years. All of them had received training in food safety and received FSCS certification. The average time per interview was 35 minutes. Observations of environmental conditions and examination of documentation such as annual reports, policy statements, employee manuals, product advertisements, and corporate advertisements were also collected in order to obtain a greater understanding of operational systems. Many interesting issues were found during analysis of the interviews. The interview data revealed that the study hotel engaged in many food safety strategies, such as safety control, marketing, and corporate organization.

3.1. Safety Control Strategies

The study hotel’s capacity to provide sufficient personnel, a training program, time, and resources was found to be the main barrier to the consistent use of a food safety control system [15,16]. As far as possible, however, the principles of the FSCS were adhered to by the various departments of the hotel, as well as the hotel’s suppliers. Production equipment; cleaning and sanitation; personal hygiene; training; chemical control; receiving, storage, and shipping; traceability and recall; and pest control (http://food.fda.gov.tw) were all subject to provisions outlined in the FSCS. The interviewees indicated that the hotel’s Food Safety Control System (FSCS) could be successfully carried out with proper layout and equipment and an effective training and assessment program.

3.1.1. Layout and Equipment

Analysis of the data from the interviews revealed that proper layout and equipment in the kitchen promoted food safety and supported food safety systems. With a more centralized kitchen, the interviewees indicated that less cost, better food quality, and less food borne risk could be achieved [13].

“Our hotel has a centralized kitchen in the basement of the building where food ingredients are pre-processed and supplied to all the kitchens in the hotel. Cost can be reduced through easier control in inventory, better deal in purchasing with large quantities, and less labor and equipment needed in each kitchen. Food quality is easier to control, not only in food freshness, texture, and portion size, but also in food safety. Different areas for different kinds of food in process and storage are designed to eliminate cross contamination. Examples of physical separation include the space of food preparation and refrigeration separated according to the food type such as seafood, meat, cold process food, hot process food, and bakery goods.” (Food and Beverage Manager, 20/07/2010, interview at the hotel office).

3.1.2. In-House Training and Assessment

Effective food safety training should be designed to closely match employees’ expectations and the organization’s goals and be accompanied by inducements that motivate staff in order to optimize training performance [13,17,18].

“In Taiwan, kitchen staffs need to have eight hours food safety seminar attendance each year or 32 hours in four years to keep chef certification valid. FSCS certified kitchen needs to have 80% of kitchen staffs with chef certifications. In addition, at least three staffs need to have additional 32 hours FSCS training course and pass qualify exam at the end of the course in order to form a FSCS team.” (Executive chef, 20/07/2010, interview at the hotel office).

For the food safety seminar, overall, the interviewees agreed that effectiveness of training is an important factor in gaining the employees’ commitment to the company’s goals in terms of the FSCS. However, all the interviewees agreed that the current training courses and certification awarded by the HACCP associations should offer a balance of practical skills development and knowledge requirements [13]. Proper food safety handling skill should also be included in training courses and assessed by both theory and a practical exam. Overall, the interviewees indicated that hotel staff who attended the HACCP courses all felt that the information sessions were overlong long and that the content was boring.

“The idea that the HACCP course focuses on both GHP and HACCP plan development seems ok theoretically. However, it is hard for our staffs to sit and listen eight hours a day. An interactive short course should be developed by incorporating more case discussion after showing real examples of HACCP operation in pictures or video rather than too much written words theory. In addition, practical skill development on food preparation should also be included.” (Personnel Manager, 20/07/2010, interview at the hotel office).

An effective training system should not be without effective food safety management and compliance assessment. The interviewees indicated that hotel food safety was supervised and audited by an assistant manager in the Stewarding department who worked closely with the executive chef, all restaurants and kitchens, and was fully empowered by the General Manager to communicate across departments on the issue of food safety. The General Manager of the hotel was very conscious of the food safety issue, and had considerable experience in the operation of hotel kitchens and FSCS implementation. He always checked and made corrections on the food safety operation while walking around the hotel, and often walked with the food safety supervisor. A video recording system was also used to assist the assessment of activities in the hotel.

“Our hotel has video camera around the food process area, and the food safety auditor will review the video to see any defaults during operation. The auditor will also walk around the kitchen floor, take pictures, and make correction. The audit report and video will be discussed with the kitchen staff during weekly meeting in which the staff will be able to identify the problem from practical examples. It is also hope to increase the staff involvement through the weekly discussion. The practical examples can also be a good material for food safety training.” (Food safety auditor, 20/07/2010, interview at the hotel office).

The Area Manager from the franchisor’s head office also conducted spot-checks of food safety standards implementation. In addition, every restaurant in the hotel formed an audit team, which then assessed the other restaurants on a monthly rotation, and reported to the executive chef. The Executive Chef in an interview indicated that temperature measuring and recording were especially important for FSCS implementation, but that not all the chefs were able to do the measuring and recording work. However, the senior management ensured that they received assistance.

“Many experienced chefs, especially in Chinese cuisine, usually have lower levels of education. Some of them have difficulty to read and write and do not have hospitality relevant degrees. Therefore, now we have kitchen stewards to assist the chef on measuring and record keeping to overcome this problem.” (Executive chef, 20/07/2010, interview at the hotel office).

As for environmental issues, many interviewees indicated that wearing disposable gloves was not necessary because, unlike the circumstances in a factory, most of their products were ready to eat after a short processing time. They noted that the bacteria on hands after proper washing was not enough to cause sickness, while the disposable gloves not only caused environmental problems, but also allowed employees to forget to actually wash their hands.

3.2. Marketing Strategies

Many studies [9,10,19,20] have shown that awareness of food safety or having the experience of food poisoning did influence consumers’ dine out decisions.

3.2.1. Transparent/Open Kitchen

The interviewees indicated that the customers’ trust concerning food safety and quality maintained or improved the company’s brand image [13]. The presentation of transparent and open kitchens staffed with employees well trained in food safety was a sign to customers that food was being prepared in a safe way and that there was nothing to hide.

3.2.2. Advertising

The hotel advertised their food safety efforts by posting where their food came from and when they received FSCS certification on both their hotel’s webpage and restaurant entrances.

3.2.3. In-House Training for the Public

In one interview, a General Manager indicated that the hotel held in-house FSCS training courses sponsored by one of the HACCP associations, and the training was not limited to their hotel staff, but that others could participate.

“At the end of the course, the trainee will take turn to observe and assess our Hotel FSCS system, then form a discussion after that. It is another way to advertising our hotel by having this activity.” (General Manager, 20/07/ 2010, interview at the hotel office).

The interviewee indicated that they hoped the customers and the trainee could judge the positive nature of the food safety effort from the dining environment and staff presentation.

3.3. Corporate Strategies

3.3.1. Corporate Social Responsibility

In this study addressing food safety issues was found to be part of the company’s policy and was documented on the mission and vision statements of the company. All the chain hotels were required to obtain food safety control system (FSCS) certification. The interviewees agreed that protecting the health and safety of the customers and employees by providing a healthy and safe environment was part of the hotel’s corporate social responsibility (CSR). Many food safety efforts made by the company are outlined in annual reports and highlighted on the hotel webpage.

3.3.2. Management Team

A FSCS management team was led by the hotel General Manager and consisted of the executive committees and other heads of department, including the Food and Beverage Manager, Chief Engineer Controller, Executive Chef, Sales and Marketing Manager, Personnel Manager, Restaurant manager, Banquet Manager, Stewards, Bar Manager. The FSCS team met monthly to discuss data gathered during assessments of the hotel, and areas needing further improvement. The General Manager indicated that FSCS was a task that needed all departments to work together in order to effectively achieve required standards of food safety.

3.4. Food Safety Strategies and Their Motivators

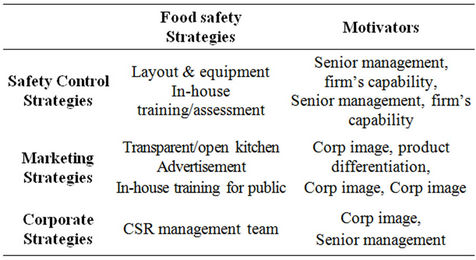

Analysis of the interviews indicates that the commitment of senior management to food safety, the firm’s capacity to act, and ideas of competitive advantage have the most positive effect on overall food safety strategies. Table 1 shows extracts of significant food safety strategies and primary motivators from the interview data.

The commitment of the management of a hotel to standards of food safety is the key driving factor for making

Table 1. Thematic conceptual matrix-food safety strategies and motivator.

the resources available for the implementation of a food safety control system [13]. In Asia, most corporations still operate on a traditional hierarchical basis in which decisions are made from the top [21]; therefore, commitment on the part of senior management is especially important. The implementation of a food safety control system in the hotel was mainly influenced by the senior management, who realized that FSCS needed the cooperation of all departments. The interviewees also indicated that a firm’s willingness to support FSCS relied on the proper provision of facilities and an in-house food safety training program with incentives to retain and motivate employees were significant motivators in promoting food safety program.

The objectives of competitive advantage are cost reduction and differentiation [22], such as developing sound safe food products to improve reputation and brand loyalty. As mentioned earlier, cost saving can be easily achieved, as well as food quality and safety, with a centralized kitchen. However, interviewees indicated that the overall cost saving was minimal, compared to the investment cost. The interviewees stated that the senior management all realized the international trend toward food safety management and were willing to invest.

The franchising company’s policy was to have all the hotels in the chain obtain food safety control system (FSCS) certification in order to create a brand image which customers could trust in terms of food safety and quality. Although the system was mostly carried out behind the centralized kitchen, transparent and open kitchen facilities in the dining areas were built for customers to see the hotel’s product differentiation and efforts to achieve food safety and quality. Advertisement on the hotel webpage and in-house training for the public on food safety issues were also used to improve the hotel’s image. One interviewee indicated that it was senior management’s intention to place food safety issues in the company’s strategic report, which can maintain or improve a company’s image. It was also the company’s policy to have a management team led by top management to run the food safety strategy more efficiently.

4. Conclusions

The main aim of this study was to understand the food safety strategies (activities) in a pioneering hotel, and the associated relationships between the motivating antecedents and food safety strategies and to determine the key motivating factors in order to provide a source of new hypotheses for further study.

This study has provided details on “what” and “how” with respect to carrying out the food safety strategies and on “how” top management commends each motivating factor. The effect of perceptions of corporate image, a firm’s capability, and senior management’s commitment to a food safety strategy in a large international chain hotel provided insight into the issues faced when attempting to encourage or mandate stronger safe food control systems. The results of this study suggest the most effective food safety practices and information for helping the hotel industry to further improve food safety strategies or practices. These findings can also be employed as a basis for further review by policy makers and educational institutions to ensure that the policy is appropriate for the hotel industry.

This study identified three key motivating factors— corporate image, firm’s capability, and senior management’s commitment—which can be developed as new hypotheses for further testing and refinement. This reduction process of data by identifying key factors is significant for forming future research.

Moreover, the result found in this study representing the relationship between the motivating factors and food safety strategies can be applied to other sectors of the food service industry or other countries confronted by similar situations and problems. The intention of this study was not to draw conclusions from the limited sample, but to provide direction for future large scale research. Therefore, any findings from the analysis of the interviewees’ responses have not been used to generalise.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization, “International Travel and Health,” 2002. http://www.who.int/ith/ITH2002.pdf

- World Health Organization, “Food Safety,” 1999. http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/general/brochure_1999/en/

- C. G. Q. Chi and H. Qu, “Examining the Relationship between Tourists’ Attribute Satisfaction and Overall Satisfaction,” Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2009, pp. 4-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19368620801988891

- B. Ozdemir, A. Aksu, R. Ehtiyar, B. Çizel, R. B. Çizel and E. T. İçigen, “Relationships among Tourist Profile, Satisfaction and Destination Loyalty: Examining Empirical Evidences in Antalya Region of Turkey,” Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, Vol. 21, No. 5, 2012, pp. 506-540. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2012.626749

- G. Fuchs and A. Reichel, “Tourist Destination Risk Perception: The Case of Israel,” Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2006, pp. 83-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J150v14n02_06

- Y. Yilmaz, Y. Yilmaz, E. T. İçigen, Y. Ekin and B. D. Utku, “Destination Image: A Comparative Study on Pre and Post Trip Image Variations,” Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, Vol. 18, No. 5, 2009, pp. 461-479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19368620902950022

- E. G. McKeown and W. B. Werner, “Content Analysis of Consumer Confidence in Food Service in Relation to Food Safety Laws, Publicity, and Sales,” Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2009, pp. 72-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19368620903327790

- M. F. Chen, “Consumer Trust in Food Safety—A Multidisciplinary Approach and Empirical Evidence from Taiwan,” Risk Analysis, Vol. 6, 2008, pp. 1553-1569. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01115.x

- A. Radam, M. L. Abu and M. R. Yacub, “Consumers’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Safety Beef Consumption,” The IUP Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. IX, No. 4, 2010, pp. 29-55.

- A. Knight, M. R. Worosz and E. C. D. Todd, “Dining for Safety Consumer Perceptions of Food Safety and Eating Out,” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2009, pp. 471-486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1096348009344211

- J. Sneed and D. Henroid, “HACCP Implementation in School Foodservice: Perspectives of Foodservice Directors,” The Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 2003. http://docs.schoolnutrition.org/newsroom/jcnm/03spring/sneed/

- S. B. Banerjee, “Corporate Environmental Strategies and Actions,” Management Decision, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2001, pp. 36-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005405

- S. L. Wu, “Factors Influencing the Implementation of Food Safety Control Systems in Taiwanese International Tourist Hotels,” Food Control, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2012, pp. 265-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.05.038

- R. K. Yin, “Case Study Research: Design and Methods,” 2nd Edition, Sage, Thousand Oaks, 1999.

- P. J. Panisello and P. C. Quantict, “Technical Barriers to Hazard Analysis Critical Point,” Food Control, Vol. 12, 2001, pp. 165-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0956-7135(00)00035-9

- L. A. Brannon, V. K. York, K. R. Robert, C. W. Shanklin and A. D. Howells, “Appreciation of Food Safety Practices Based on Level of Experience,” Journal of Foodservice Business Research, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2009, pp. 1-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15378020902910462

- G. C. Ogbeide, “A Case Study of Restaurant Training Motivations and Outcomes,” International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2008, pp. 72-177.

- J. Salazar, H. R. Ashraf, M. Tchebg and J. Antun, “Food Service Employee Satisfaction and Motivation and the Relationship with Learning Food Safety,” Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2005, pp. 93-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J385v04n02_07

- A. Knight, E. C. D. Todd and M. R. Worosz, “Dining for Safety Consumer Perceptions of Food Safety and Eating Out,” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2009, pp. 471-486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1096348009344211

- U. Z. A. Ungku Fatimaha, H. C. Boo, M. Sambasivan and R. Salleh, “Foodservice Hygiene Factors—The Consumer Perspective,” International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2011, pp. 38-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.04.001

- Y. Boshy, “Action Learning Worldwide,” Palgrave, New York, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9781403920249

- R. Welford, “Corporate Environmental Management 1: Systems and Strategies,” Earthscan, London, 1998.