Open Journal of Orthopedics

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:29482,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojo.2013.31009

Hip Arthroscopy in Children under the Age of Ten

![]()

Orthopaedic Department, Olgahospital Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany.

Email: o.eberhardt@klinikum-stuttgart.de

Received January 5th, 2013; revised February 12th, 2013; accepted February 21st, 2013

Keywords: Hip Arthroscopy; Hip Disorders; Arthroscopic Surgery; Minimal Invasive Surgery

ABSTRACT

Arthroscopic hip surgery has become an established diagnostic and therapeutic method for addressing different hip pathologies. This paper focuses on hip arthroscopy for treating hip disorders in children under the age of 10. Arthroscopic hip surgery was performed 30 times on 24 children to address various hip pathologies. Indications were septic arthritis, benign soft tissue tumors, traumatic and congenital hip dislocation, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and osteochondroma of the acetabulum. Diagnostic arthroscopy was technically feasible in all cases. All cases of septic arthritis were successful treated using arthroscopic lavage and antibiotics. In the miscellaneous cases (benign fibrous tumor, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, osteochondroma congenital hip dislocations and traumatic hip dislocation) 4 hips had additional open surgery including surgical dislocation with synovectomy, open reduction and stabilization of the fractured posterior rim of the acetabulum, acetabulopasty and open resection of an osteochondroma with acetabuloplasty. In conclusion arthroscopic hip surgery is an additional diagnostic and therapeutic method that is suitable for treating different hip pathologies in children under the age of 10. Primary treatment of septic arthritis can be done easy by hip arthroscopy. Using cannulated mini arthroscopic hip instruments (2.7 mm), the range of application can be expanded to include treatment of very young infants. Hip arthroscopy can reduce the need of open surgery but cannot replace bony procedures in hip surgery.

1. Introduction

Previously, arthrotomy with or without surgical dislocation has been the standard procedure for treating intraarticular diseases in children.

In recent years, arthroscopic hip surgery has become a standard diagnostic and therapeutic method in adults [1-3]. It is increasingly used to treat femoroacetabular impingement, chondromatosis, as well as other degenerative and inflammatory diseases of the hip joint.

There is considerably less experience with arthroscopic hip surgery in children and adolescents than in adults [4]. Initial reports on the arthroscopic anatomy of the hip joint in children for various diseases were published by Groß in 1977 [5]. In the 1980s, Holgersen (1981) reported on his experience with chronic juvenile arthritis and Bowen et al. (1986) published their results on using hip arthroscopy to treat osteochondritis dissecans [6,7]. Chung et al. (1993) carried out arthroscopic lavage to treat septic arthritis in children [8]. Further indications for arthroscopic surgery in children include Perthes disease, femoral head epiphysiolysis, hip dysplasia, femoroacetabular impingement, synovial diseases, intraarticular tumors, avascular necrosis, loose joint bodies, and flake fractures [1,9-12]. In this paper, we report about our experience using hip arthroscopy in children under the age of 10. We present diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities for its implementation in children.

2. Materials and Methods

Between January 2008 and December 2010, arthroscopic hip surgery was performed 30 times on 24 children. Indications were septic arthritis, traumatic and congenital hip dislocation, and ambiguous boney and soft-tissue changes.

The arthroscopic procedure was adjusted according to intraoperative findings. Arthroscopic measures included diagnostic arthroscopy, the resection of pathological ligamentous structures, capsule release, joint lavage, biopsies, partial synovectomies and the removal of loose bodies. The patients demographic data, complications, and post-operative progress were prospectively documented.

Surgical Technique

Hip arthroscopy is performed with patients under general anesthesia in a prone position on an extension table or a standard child’s operating table. The hip joint consists of two arthroscopic compartments, a central compartment and a peripheral compartment. Standard portals for the central compartment are an anterior, an anterolateral and a posterolateral portal. The anterolateral portal is located 2 cm distal to the superior iliac spine and 1 cm lateral from a line drawn through the superior iliac spine and the middle of the patella. The anterior portal is located anterior to the greater trochanter. The posterior portal is located posterior to the greater trochanter.

The femoral head, the labrum, the acetabulum, teres ligament, transverse ligament could be visualized in the central compartment. For the peripheral compartment we used a high anterolateral portal and an anterior portal [1]. Anatomical structures in the peripheral compartment are the femoral head, femoral neck, labrum, medial and lateral synovial fold and zona orbicularis. The scope is introduced in all the different portals to visualize different parts of the hip joint. In children with congenital dislocated hips we used a subadductor medial portal and an anterolateral portal. The subadductor portal is for the 70˚ scope and the anterolateral portal is for the surgical instruments. The subadductor portal is located 1 cm lateral and 1 cm anterior to the ischial tuberosity. The procedure was performed with 6 mm standard cannulated arthroscopic instruments or 2.7 mm cannulated mini-arthroscopic instruments and a 70˚ scope. The portals are placed under fluoroscopy using a puncture needle, a flexible guide wire and a cannulated trocar.

The surgical instruments are a shaver with a 3.4 mm resector, 4 mm standard electrocautery probe, a hook punch and a hook scissor. In our series an extension table was not used for patients with septic arthritis and congenital hip dislocations. In cases of septic arthritis traction was performed manually. Arthroscopic joint lavage was carried out through the peripheral joint compartment using a two-portal technique. Post-op we used in this cohort no immobilization in a spica cast.

3. Results

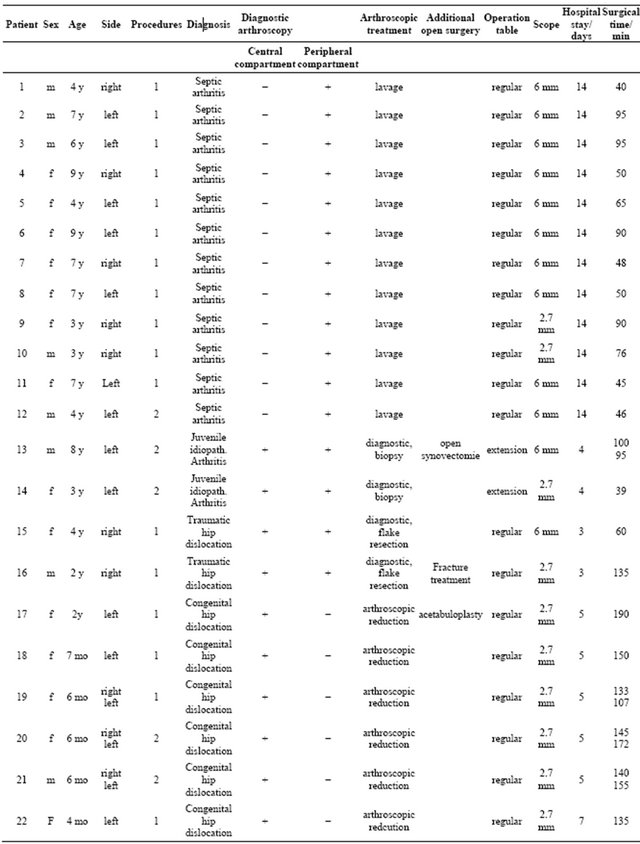

Between January 2008 and December 2010, arthroscopic hip surgery was performed 30 times on a total of 24 children under the age of 10. The patients comprised 9 boys and 15 girls with an average age of 3.5 years (4 months through 9 years). 12 patients had septic arthritis, 2 suffered from traumatic hip dislocation, and 6 had a congenital hip dislocation. One patient had a benign soft tissue tumor (fibroma), 2 had juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and one patient presented with acetabular osteochondroma. Patients were observed for a period of between 2 months and 5 years. All patients in the study population had a stationary hospital stay of between 3 and 14 days (mean stay 8.6 days). Surgery lasted between 40 and 172 minutes (mean duration 101 minutes). The data are summarized in Table 1.

3.1. Results Septic Arthritis

11 patients with septic arthritis received a singular arthroscopic lavage using a two-portal technique. In one case, a second arthroscopic lavage was carried out after 3 days. The detected germs were staph. aureus, staph. warneri, and salmonella enteritidis. All patients were pain-free and had complete mobility after 2 weeks of stationary treatment with intravenous antibiotics. Patients were released from the hospital when their CRP had decreased to <0.3 mg/dl, except for one patient who was released with 0.8 mg/dl. Radiological follow-up showed that one patient had changes of the femoral head. A second arthroscopy confirmed the diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. All other patients with septic arthritis were subsequently symptom-free with full mobility.

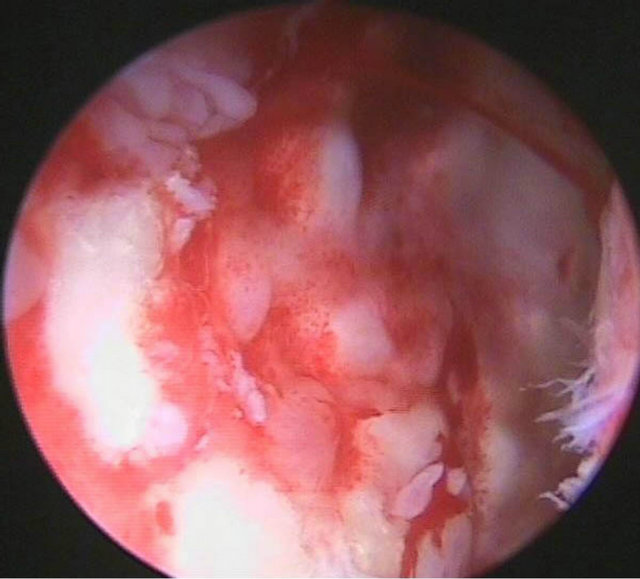

3.2. Results Synovial Disorders and Tumors

One patient with a hip joint effusion underwent arthroscopy to rule out possible septic arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). PVNS and septic arthritis were ruled out histiologically. We used Krenn’s synovitis score to determine the severity of synovitis [13]. The tentative diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis was confirmed, classified, and medical treatment initiated under consideration of the degree of synovitis. During the course of treatment, one patient with juvenile idiopathic arthritis required open synovectomy with surgical dislocation.

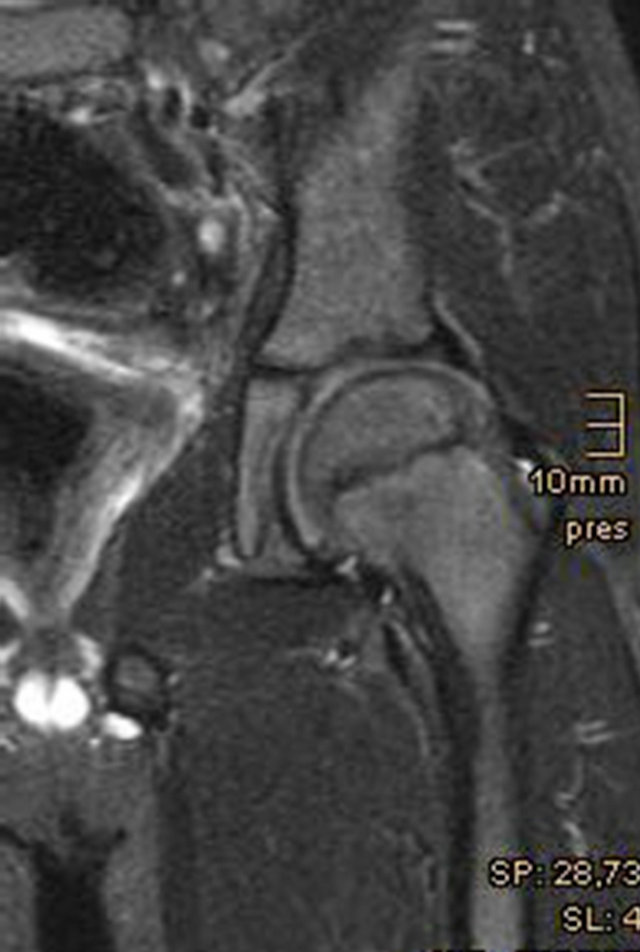

Following diagnostic arthroscopy and biopsy of the patient with the intraarticular tumor (fibroma), a complete resection of the tumor was successfully carried out in a second arthroscopic procedure. After three months, the symptoms had completely subsided and the patient could return to full physical activity. A follow-up MRI documented the tumor-free progress (Figures 1(a)-(c)).

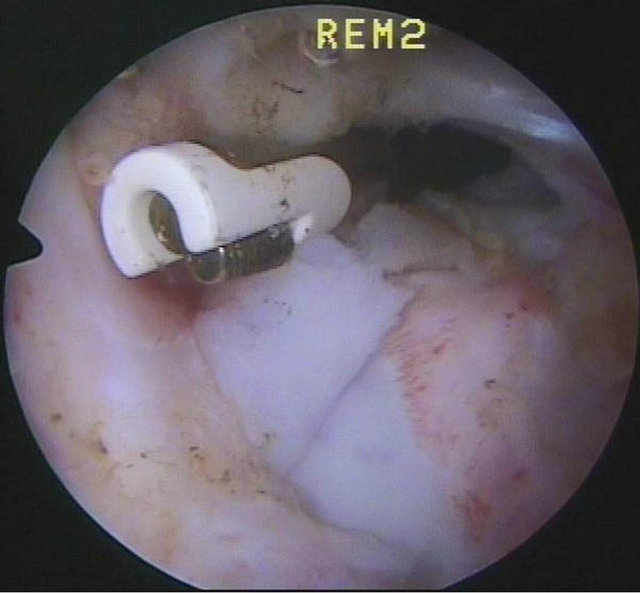

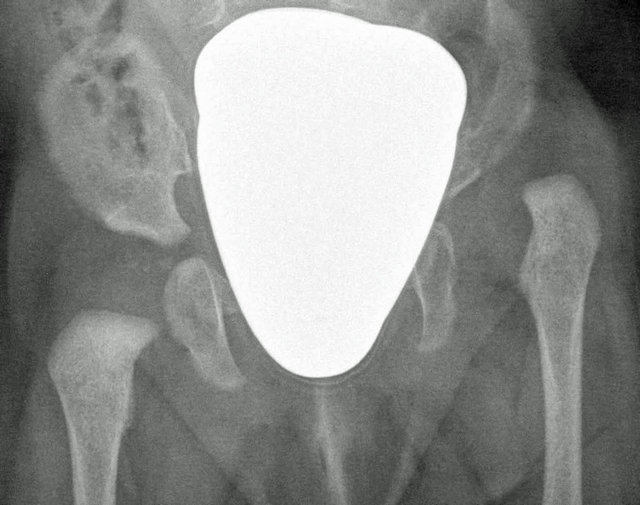

In the case of the patient with osteochondroma of the acetabulum, we initially attempted to remove the exostosis arthroscopically (Figures 2(a), (b)). The arthroscopic approach was limited. During the procedure we had to change to an open procedure, and carried out an open resection of the exostosis with additional acetabuloplasty.

3.3. Results Congenital Hip Dislocation

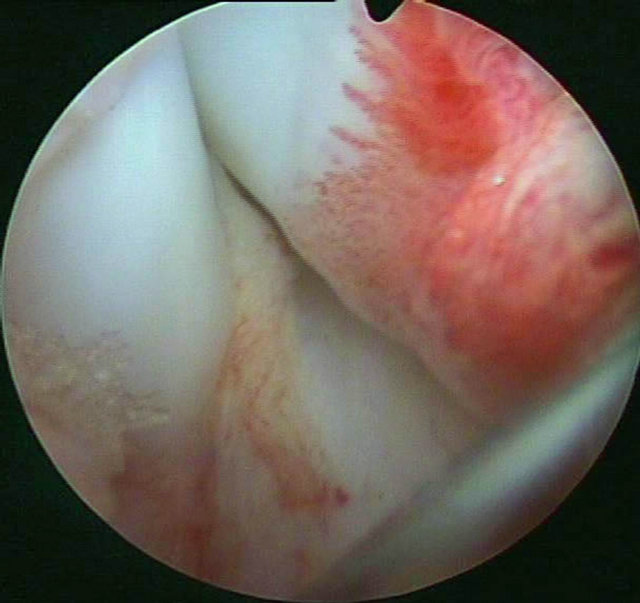

All patients had a trial of a closed reduction. Closed reduction and treatment with a spica cast or a Pavlik harness was in all cases unsuccessful. Arthroscopic surgery was possible in all 6 patients with 9 congenital hip dislocations. All important anatomical structures could be visualized introducing the scope through a medial subadductor portal (Figure 3(a)). Main obstacle for reduction was in all cases capsule constriction. Following arthroscopic resection of the teres ligament (Figure 3(b))Table 1. Patients data, diagnosis and surgical procedures.

Continued

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c)

Figure 1. (a) Peripheral compartment, medial neck area with soft tissue tumor; (b) Pre-op MRI, soft-tissue tumor in the periphereal Compartment of the hip; (c) Post-op MRI after tumor extirpation.

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 2. (a) Radiograph of an acetabular osteochondroma (Trevor disease); (b) Arthroscopic view of the acetabular osteochondroma.

resection of the fatty tissue in the acetabulum and a capsule release, all dislocated hip joints were reduced by a single arthroscopic approach. In one case we performed an additional Pemberton acetabuloplasty. Post-op reducetion was confirmed using MRI. With subsequent stabilization using a spica cast all hips remained stable (Figures 3(c), (d)). At a mean follow-up of 13.2 months (9 - 24 months) 3 out of 9 hips developed not an ossified nucleus, had metaphyseal changes and must be regarded as having avascular necrosis.

3.4. Results Traumatic Hip Dislocation

Two children with traumatic hip dislocation underwent hip arthroscopy. The first case, age 4 years, showed an avulsion fracture of the teres ligament (Figures 4(a), (b)). Flake and ligament were resected arthroscopically. A postop cast for 3 weeks was applied. After 3 months the

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c) (d)

(d)

Figure 3. (a) Arthroscopic view of a congenital hip dislocation, femoral head dislocated behind the posterior rim of the acetabulum; (b) Resection of the teres ligament with electrocautery; (c) Preop radiograph, left side dislocated; (d) Follow-up 10 months after arthroscopic reduction with concentric reduction.

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c)

Figure 4. (a) Radiograph of a 4-year-old girl with traumatic hip dislocation; (b) Avulsion of the teres ligament with osteochonral flake fracture; (c) 6 months follow-up MRI, concentric reduction without avascular necrosis.

patient had free range of motion. MRI after 2 years showed no avascular necrosis. The second case was more complex, age 2 years. Hip arthroscopy showed avulsion of the teres ligament but also a fracture of the posterior rim of the acetabulum. Open stabilization was performred using a posterior approach. Similar to the first case a cast was applied for 3 weeks. The boy returned to full activity within 3 months.

3.5. Complications

Transient dysesthesia was not observed, as far as this is possible to evaluate in infants and small children under the age of 10. No motor or neurological complications were observed, particularly no pudendal lesions, sciatic or femoral paresis. No hematomas or pressure lesions were observed in the genital area.

4. Discussion

Arthroscopic hip surgery is a minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedure which is becoming increasingly important for treating children. Today, arthroscopy is an integral procedure of modern hip surgery, and is seldom considered a rival to arthrotomy or osteotomies of the femur and pelvis. Primarily, however, arthroscopic hip surgery offers new diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities. Indications for arthroscopy in children and adolescents include losse bodies, synovial diseases, Perthes disease, avascular necrosis, femoral head epiphysiolysis, labral pathologies, hip dysplasia, tumors of the hip joint, trauma, and septic arthritis [1,4,8,10,12].

4.1. Septic Arthritis

The previous standard treatment for septic arthritis in children consisted of an arthrotomy with joint lavage and subsequent antibiotic treatment [14-16]. Arthroscopic lavage has become the generally accepted treatment of choice in children’s knee joints. Arthroscopy to treat septic arthritis of the hip is being increasingly recommended [8,10,17-21]. Chung et al. (1993) reported their experiences with children between the ages of 2 and 7. They implemented a 5 mm 30˚ arthroscope and a two-portal technique. In children under the age of 5, traction was performed manually and an extension table was not used [8]. El Sayed (2008) compared arthroscopic and open joint lavage. He used a two or three portal technique and an extension table. Antibiotic treatment was administered for 10 days intravenously and for four weeks orally. Children who received an arthroscopic joint lavage had a shorter hospital stay and were mobilized more quickly than children who received an arthrotomy [18].

In our cohort, 12 children with septic arthritis were treated arthroscopically. Surgery was performed using a two-portal technique, a 6 mm standard cannulated arthroscopic hip instrument (Wolf®) and special 2.7 mm cannulated mini arthroscopic hip instruments (Wolf®). Only the peripheral joint compartment was accessed arthroscopically using a high anterolateral and an anterior portal. An extension table was not used for any of the patients. Traction of the hip joint was done only manually. Arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritis of the hip joint is a safe alternative to an arthrotomy. It is minimally invasive, is associated with a lower mortality rate, and enables the child to recover more quickly.

In the authors’ view, arthroscopic hip surgery is the method of choice for treating septic arthritis. In our clinical practice, joint lavage via arthrotomy is only carried out in exceptional cases. The duration of hospitalizetion in our practice is still determined by the 14-day treatment with intravenous antibiotics.

4.2. Synovial Diseases and Intraarticular Tumors of the Hip

Intraarticular tumors of the hip joint are rare diseases. Hemangiomas, lipomas, benign synovial diseases such as giant cell nodular tumor, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and synovial chondromatosis, are described as intraarticular soft tissue tumors [1,22-25]. Malign tumors include synovial sarcomas and myxofibrosarcomas [26,27]. Arthroscopic resections of tumors in the hip joint have been described for cartilaginous exostosis, intraarticular hemangiomas, and for acetabular osteoid osteomas [22,28,29]. Pain reductions and improvements in mobility have been shown in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis [7].

In our patient cohort, 4 patients had synovial diseases or intraarticular space occupying lesions; 2 had idiopathic juvenile arthritis, one had a fibroma in the peripheral hip compartment (Figures 1(a)-(c)), and one patient presented with central acetabular exostosis (Figures 2(a), (b)). The fibroma was resected arthroscopically and the 7-year-old boy was symptom-free post-procedure. A post-operative MRI examination confirmed complete resection of the tumor (Figure 4(d)). In the patient with central acetabular exostosis, additional acetabuloplasty was carried out following resection.

For juvenile arthritis, arthroscopy is used to confirm the diagnosis and enables a partial synovectomy to be carried out. An improvement in the medical symptoms has been reported following arthroscopic synovectomy in infants and small children. We implemented arthroscopy with our patients to confirm the diagnosis and exclude PVNS. In both cases, the synovitis score according to Krenn was determined [13]. The patients’ improvements, however, must also be considered in the context of the modified medication according to their synovitis score. Overall, arthroscopic hip surgery is a good procedure for performing biopsies. Using the appropriate position, benign tumors can be removed arthroscopically and at least partial synovectomies are possible [4,22,23,29].

4.3. Trauma

Traumatic pathologies of the hip join include lesions of the labrum, cartilage lesions, and ruptures of the teres ligament. Sports with repetitive flexion and abduction movements, such as gymnastics, skating, or dancing, are particularly predisposing for labrum lesions. Debridement and refixation of the labrum in adolescent athletes has also been described in previous studies, although currently labrum refixation can only be carried out at special medical centers [30,31]. The arthroscopic extirpation of free joint bodies in the case of flake fractures is technically feasible [1,10,12]. Kashiwagi et al. (2001) reported an avulsion injury of the teres ligament after repositioning a traumatic hip dislocation [32]. We had two posterior traumatic hip dislocations in our cohort [33]. Only through arthroscopy was it possible to ascertain the magnitude of injury in a 2-year-old boy, who presented with a fracture in the posterior rim of the acteabulum. Controlled repositioning of the dislocated hip of a 4-year-old boy was done arthroscopically. In this case, we also found an avulsion of the teres ligament with a chondral flake fracture, which was was arthroscopically resected together with the teres ligament (Figures 4(a)- (c)).

4.4. Congenital Hip Dysplasia and Hip Dislocation

Due to hip screenings during infancy, most dislocated hips can be treated conservatively [34]. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, standard procedure is then open repositioning using an inguinal or medial approach.

In 1977, Gross was the first to carry out arthroscopic hip surgery on dislocated hip joints. Using arthroscopy, he was able to confirm existing diagnostic and anatomical knowledge. He did not carry out therapeutic measures, such as arthroscopic reduction [5]. Hasan and Al Sabti (1995) carried out 5 diagnostic hip arthroscopies on dislocated hips [35]. Bulut et al. (2005) reported 4 successful arthroscopically assisted repositioning measures. Using a medial portal, an open tenotomy was carried out on the psoas tendon and the arthroscope was inserted through a medial portal [36]. McCarthy and McEwen (2007) performed arthroscopic reduction on 3 patients using an anterolateral and a posterolateral portal [37]. We introduced arthroscopic reduction of the dislocated hip in infants in our clinic in 2009. We presented our early experience in 2012 [38]. We use a medial subadductor portal and an anterolateral portal in 6 patients. All important anatomical structures can be imaged through the subadductor portal. The patients’ ages in the presented series were between 4 and 29 months. All reduced hip joints remained stable throughout the course of the study. Using 2.7 mm cannulated mini instruments, arthroscopic hip surgery of dislocated hips in infants and toddlers can be safely performed via a subadductor portal and an anterolateral portal. There are currently no intermediate results on arthroscopic procedures. In our series the mean follow-up was 13.2 months. According to the Salter classification we had 3 severe AVN cases. Therefore additional examinations are necessary, in particular to evaluate the functional results.

In summary, arthroscopic hip surgery has become an important part in modern hip surgery in children. Its breakthrough has been aided by the development of cannulated hip instruments and of standardized portals and surgical techniques. In addition, initial strict adherence to standardized techniques will avoid mistakes in positioning instruments and portals [1]. Hip arthroscopy is seldom considered a rival to bony procedures like osteotomies at the femur or the pelvis as shown in our cases in which we performed additional acetabuloplasty. It offers new diagnostic and therapeutic options.

Indications for hip arthroscopy in children and adolescents are Perthes disease, ECF, FAI, AVN, free joint bodies, traumatic lesions with injuries to the cartilage and labrum, synovial diseases, and benign tumors.

Our series with 24 children and 30 hip arthroscopies demonstrates the effectiveness of arthroscopic hip surgery in treating various hip pathologies. In this study, arthroscopic hip surgery was performed on children under the age of 10. It thereby became clear that there is a considerable difference between the indications in younger children and those older than 10 years of age. Most studies of arthroscopic hip surgery in children deal with adolescent patients and femoroacetabular impingement as a secondary deformity in perthes disease and slipped capital femoral epiphysis [4,10,12]. The main indication for hip arthroscopy in children under the age of 10 is septic arthritis. Special indications include synovial changes, benign soft tissue tumors, traumatic and congenital hip dislocation. Arthroscopic reduction of congenital hip dislocation is not a standard treatment. Currently there are only a few cases reported in the literature without mid-term or long-term results [36-38]. So arthroscopic reduction of congenital dislocated hip joints is reserved for paediatric centres with experience in arthroscopic hip surgery. In contrast, septic arthritis can be treated easily, quickly, and effectively through arthroscopic surgery. Thus, in our opinion an arthrotomy is only necessary in exceptional cases.

REFERENCES

- M. Dienst, “Lehrbuch und Atlas Hüftarthroskopie Diagnostik—Technik—Indikationen,” Elsevier Urban & Fischer, München, 2009.

- M. J. Philippon, K. Briggs, Y.-M. Yen and D. A. Kuppersmith, “Outcomes Following Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacteabular Impingement with Associated Chondrolabral Dysfunction,” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery , Vol. 91, No. 1, 2009, pp. 16-23.

- M. Wettstein and M. Dienst, “Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement,” Orthopäde, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2006, pp. 85-93. doi:10.1007/s00132-005-0897-3

- M. S. Kocher, Y. J. Kim, M. B. Millis, R. Mandiga, P. Siparsky, L. J. Micheli and J. R. Kasser, “Hip Arthroscopy in Children and Childhood,” Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, Vol. 25, No. 5, 2005, pp. 680-686. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000161836.59194.90

- R. Gross, “Arthroscopy in Hip Disorders in Children,” Orthopedic Reviews, Vol. 6, No. 9, 1977, pp. 43-49.

- J. R. Bowen, V. P. Kumar, J. J. 3rd Joyce and J. C. Bowen, “Osteochondritis Dissecans Following Perthes Disease. Arthroscopic Operative Treatment,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, Vol. 209, 1986, pp. 49- 56.

- S. Holgerson, H. Brattström, B. Morgenson and L. Lidgren, “Arthroscopy of the Hip in Juvenile Chronic Arthritis,” Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, Vol. 1, No 3, 1981, pp. 273-278. doi:10.1097/01241398-198111000-00006

- W. K. Chung, G. L. Slater and E. H. Bates, “Treatment of Septic Arthritis of the Hip by Arthroscopic Lavage,” Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, Vol. 13, No. 4, 1993, pp. 444-446.doi:10.1097/01241398-199307000-00005

- C. Lampert, “Hüftarthroskopie bei Kindern und Jugendlichen,” In: M. Dienst, Ed., Lehrbuch und Atlas Hüftarthroskopie, Elsevier Urban & Fischer, München, 2009.

- D. Roy, “Arthroscopy of the Hip in Children and Adolescents,” Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2009, pp. 89-100. doi:10.1007/s11832-008-0143-8

- N. A. DeAngelis and B. H. Busconi, “Hip Arthroscopy in the Pediatric Population,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, Vol. 406, No. 1, 2003, pp. 60-63. doi:10.1097/00003086-200301000-00010

- P. Jayakumar, M. Ramachandran, T. Youm and P. Achan, “Arthoscopy of the Hip for Paediatric and Adolescent Disorders. Current Concepts,” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br), Vol. 94, No. 3, 2012, pp. 290-296. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B3.26957

- V. Krenn, L. Morawietz, G. R. Burmester and T. Häupl, “Synovialitis-Score: Histopathological Grading System for Rheumatic and Non-Rheumatic Synovialitis,” Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie, Vol. 64, No. 5, 2005, pp. 334- 342. doi:10.1007/s00393-005-0704-x

- F. Hefti, “ Paediatric Orthopaedics in Practice,” 2nd Edition, Springer Verlag Heidelberg, Philadelphia 2006.

- J. A. Herring, “Tachdjian’s Pediatric Orthopaedics,” 4th Edition, Saunders, Philadelphia, 2007.

- E. Rutz and R. Brunner, “Septic Arthritis of the Hip—Current Concepts.” Hip International, Vol. 19, Suppl. 6, 2009, pp. 9-12.

- I. Nusem, M. K. Jabur and E. G. Playford, “Arthroscopic Treatment of Septic Arthritis of the Hip,” Arthroscopy, Vol. 22, No. 8, 2006, p. 902. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.057

- A. M. El-Sayed, “Treatment of Early Septic Arthritis of - the Hip in Children: Comparisonof Results of Open Arthrotomy versus Arthroscopic Drainage,” Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2008, pp. 229- 237. doi:10.1007/s11832-008-0094-0

- Y. Yamamoto, T. Ide, N. Hachisuka, S. Maekawa and N. Akamatsu, “Arthroscopiy Surgery for Septic Arthritis of the Hip Joint in 4 Adults,” Arthroscopy, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2001, pp. 290-297. doi:10.1053/jars.2001.20664

- M. Bould, D. Edwards and R. N. Villar, “Arthroscopic Diagnosis and Treatment of Septic Arthritis of the Hip Joint,” Arthroscopy, Vol. 9, No. 7, 1993, pp. 707-708. doi:10.1016/S0749-8063(05)80513-4

- S. J. Kim, N. K. Choi, S. H. Ko, J. A. Linton and H. W. Park, “Arthroscopic Treatment of the Arthritis of the Hip,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, Vol. 407, 2003, pp. 211-214. doi:10.1097/00003086-200302000-00030

- S. J. Kim, S. H. Cho and D. H. Ko, “Arthroscopic Excision of Synovial Hemangioma in the Hip Joint,” Journal of Orthopaedics Science, Vol. 13, No. 4, 2008, pp. 387-389. doi:10.1007/s00776-007-1232-0

- F. Margheritini, R. N. Villa and D. Rees, “Intra-Articular Lipoma of the Hip,” International Orthopaedics, Vol. 22, No. 5, 1989, pp. 328-329. doi:10.1007/s002640050271

- V. E. Krebs, “The Role of the Hip Arthroscopy in the Treatment of Synovial Disorders and Loose Bodies,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, Vol. 406, 2003, pp. 48-59. doi:10.1097/00003086-200301000-00009

- J. Bruns, O. Yazigee and C. R. Habermann, “Pigmented Villo-Nodular Synovial Giant-Cell Tumors,” Zeitschrift für Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie, Vol. 146, No. 5, 2008, pp. 663-675. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1038724

- S. Okamoto, T. Ishida, H. Ohnishi. R. MacHinami and H. Hashimoto, “Synovial Sarcomas of Three Children in the First Decade: Clinicopathological and Molecular Findings,” Pathology International, Vol. 50, No. 10, 2000, pp. 818-823. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01122.x

- D. Viejo-Fuertes, M. Mousny, P. L. Docquier, J. E. Dubuc, F. Lecouvet, H. Noel and J. J. Rombouts, “Intraarticular Myxofibrosarcoma of the Hip in a 10-Year-Old Child,” Revue de Chirurgie Orthopedique et Reparatrice de l’Appareil Moteur, Vol. 90, No. 2, 2004, pp. 161-164. doi:10.1016/S0035-1040(04)70040-9

- M. S. Alvarez, P. R. Moneo and J. A. Palacios, “Arthroscopic Exstirpation of an Osteoid Osteoma of the Acetabulum,” Arthroscopy, Vol. 17, No. 7, 2001, pp. 768-771. doi:10.1053/jars.2001.22417

- F. Bonnomet, P. Clavert, F. Z. Abidine, P. Gicquel, J. M. Clavert and J. F. Kempf, “Hip Arthroscopy in Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: A New Perspective of Treatment,” Arthroscopy, Vol. 17, No. 9, 2001, pp. 1-4. doi:10.1053/jars.2001.22410

- M. Dienst and D. Kohn, “Hip Arthroscopy. Minimal Invasive Diagnosis and Therapy of the Diseased or Injured Hip Joint,” Unfallchirurg, Vol. 104, No. 1, 2001, pp. 2-18. doi:10.1007/s001130050682

- M. J. Philippon, “New Frontiers in Hip Arthroscopy: The Role of Arthroscopic Hip Labral Repair and Capsulorhaphy in Treatment of Hip Disorders,” Instructional Course Lectures, Vol. 55, 2006, pp. 309-316.

- N. Kashiwaga, S. Suzuki and Y. Seto, “Arthroscopic Treatment for Traumatic Hip Dislocation with Avulsion Fracture of the Ligament Teres,” Arthroscopy, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2001, pp. 67-69. doi:10.1053/jars.2001.8024

- F. F. Fernandez, T. Wirth and O. Eberhardt, “Acute Traumatic and Especially Neglected Traumatic Hip Dislocation Are Very Rare in Children,” Unfallchirurg, Vol. 115, No. 9, 2012, pp. 830-835. doi:10.1007/s00113-011-2036-4

- T. Wirth, L. Stratmann and F. Hinrichs, “Evolution of Late Presenting Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip and Associated Surgical Procedures after 14 Years of Neonatal Ultrasound Screening,” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br), Vol. 86, No. 4, 2004, pp. 585-589.

- H. A. R. Hasan and A. Al-Sabti, “Arthroscopy of the Hip in Congenital Dislocation,” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br), Vol. 77-B, Suppl. 1, 1995, pp. 1-26.

- O. Bulut, H. Oztürk, G. Tezeren and S. Bulut, “Arthroscopic-Assisted Surgical Treatment for Developmental diSlocation of the Hip,” Arthroscopy, Vol. 21, No. 5, pp. 574-579. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2005.01.004

- J. J. McCarthy and G. D. MacEwen, “Hip Arthroscopy for the Children with Hip Dysplasia a Preliminary Report,” Orthopedics, Vol. 30, No. 4, 2007, pp. 262-265.

- O. Eberhardt, F. F. Fernandez and T. Wirth, “Arthroscopic Reduction of the Dislocated Hip in Infants,” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br), Vol. 94, No. 6, 2012, pp. 842-847. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B6.28161