Open Journal of Stomatology

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:28819,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojst.2013.31009

Activation of cannabinoid receptor CB2 regulates LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and osteoclastogenic gene expression in human periodontal ligament cells

![]()

1Department of Orthodontics, School of Stomatology, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China

2Department of General Surgery, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China

3Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China

4Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China

Email: *qianred212@hotmail.com

Received 18 January 2013; revised 24 February 2013; accepted 4 March 2013

Keywords: Cannabinoid Receptor CB2; Lipopolysaccharide; Human Periodontal Ligament Cells; IL-1β; IL-6; TNF-α; OPG; RANKL

ABSTRACT

Background and Objective: It has been found that human periodontal ligament (hPDL) cells express cannabinoid receptor CB2. However, the functional importance of CB2 in hPDL cells exposed to bacterial endotoxins is not known. Here we investigate if the inflammation promoter lipopolysaccharide (LPS) affects CB2 expression and if activation of CB2 regulates LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and osteoclastogenic gene expression in hPDL cells. Methods: The hPDL cells were obtained from extracted teeth of periodontally healthy subjects. CB2 expression in hPDL cells exposed to LPS was determined by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Then, the cells were incubated with or without CB2-specific agonist HU-308 before further stimulation with LPS. In some experiments, the cells were pre-treated with CB2-specific antagonist SR144528. The production of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 beta (IL- 1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factoralpha (TNF-α) was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The mRNA expression of osteoclastogenic genes osteoprotegerin (OPG) and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) was examined using quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Results: CB2 expression in hPDL cells was markedly enhanced by LPS. HU-308 significantly suppressed the production of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α exposed to LPS, whereas SR144528 attenuated this effect. The OPG/RANKL ratio decreased when exposed to LPS, furthermore increased significantly with the addition of HU-308 and finally decreased markedly after pretreatment with SR144528. Conclusion: Our study demonstrated that activation of CB2 had anti-inflammatory and anti-resorptive effects on LPS-stimulated hPDL cells. These findings suggest that activation of CB2 might be an effective therapeutic strategy for the treatment of inflammation and alveolar bone resorption in periodontitis.

1. INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone resorption. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) play a key role in the destruction of periodontal tissues, including the gingiva, periodontal ligament (PDL), and alveolar bone, through the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and prostaglandin (PG) [1]. The PDL is a highly vascularized and cellularized connective tissue that attaches the tooth root to the surrounding alveolar bone [2]. The PDL cells not only function as support cells for periodontal tissues, but also produce various inflammatory mediators to recognize somatic components, including LPS [3]. In addition, the PDL cells modulate osteoclastogenesis by expression of osteoprotegerin (OPG) and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) [4,5]. OPG and RANKL, both expressed in osteoblasts, have been shown to play a key role in the regulation of osteoclastogenesis. RANKL binds its receptor RANK on the osteoclast precursor surface, determining their activation and differentiation into mature osteoclasts [6-8]. OPG exerts its effect by acting as a RANKL decoy receptor, thus preventing its binding to osteoclasts and inhibiting osteoclast activation [6,9]. Therefore, the PDL cells participate in the regulation of inflammatory responses and alveolar bone resorption of periodontitis.

Cannabinoids refer to a heterogeneous group of molecules that bind to cannabinoid receptors. They can be divided into three groups: endogenous (endocannabinoids), synthetic, and phytocannabinoids [10]. The endocannabinoid system consists of endogenous ligands and receptors being subject to modulation by natural and synthetic cannabinoid agonists, and plays important modulatory functions in the brain and also in the periphery [11]. There is an abundance of evidence demonstrating the anti-inflammatory actions of cannabinoids [12,13]. It is widely assumed that the majority of such effects are mediated by the cannabinoid receptor CB2, which is expressed by a wide range of immune cells [14]. Moreover, CB2 has been found to play a crucial role in the regulation of bone metabolism [15-17]. Animal experiments have demonstrated that CB2-deficient mice display a markedly accelerated age-related bone loss and activation of CB2 attenuates ovariectomy-induced bone loss in mice by enhancing bone formation and restraining bone resorption [16]. However, the molecular mechanisms of CB2 in inflammatory responses and bone metabolism have not been fully elucidated.

It has been found that hPDL cells express CB2, and activation of CB2 is able to enhance osteogenic differentiation of hPDL cells and potentially create a favorable osteogenic microenvironment [14]. However, the functional importance of CB2 in hPDL cells exposed to the inflammation promoter LPS is not known. We hypothesized that LPS might affect CB2 expression and activation of CB2 might regulate LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and osteoclastogenic gene expression in hPDL cells. Thus, we undertook the present study to verify this hypothesis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cell Culture

Healthy hPDL tissue was obtained from the extracted (for orthodontic reasons) premolars of two females (13 and 14 years old) and one male (12 years old). All patients gave written informed consent before tooth extraction. Ethical approval had been obtained from the Ethics Committee of Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China. As described previously [18], the PDL tissue attached to the mid-third of the root surface was scraped off, cut into small pieces and placed into tissue culture flasks. The explants were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma, St LouisMO, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), 100 U/mL of penicillin and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere of air enriched with 5% CO2. When the hPDL cells growing from the tissue fragments reached confluence, the cell layer was rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and the cells were released with 0.25% trypsin—0.1% EDTA solution. The hPDL cells used in this study were from passage 3 - 5.

2.2. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of CB2

The hPDL cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 per well and were allowed to attach for 12 h. The cells were then silenced with serum-free DMEM overnight. The cells were stimulated with or without 100 ng/ml Escherichia coli 0111:B4 LPS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 12 h and 24 h. To quantify the mRNA expression of CB2, we performed quantitative real-time PCR using Prime-ScriptTM RT Reagent Kit Perfect RealTime with a SYBR Green Reagent (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co. Ltd) in the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer sequences and product sizes of each gene [CB2 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)] were adapted from Reference 18. The cycling conditions for each gene were as follows: CB2, 94˚C for 3 min, followed by 94˚C for 30 s, 65˚C for 30 s and 72˚C for 40 s for 35 cycles, and 72˚C for 5 min; and GAPDH, 94˚C for 3 min, followed by 94˚C for 30 s, 60˚C for 30 s and 72˚C for 30 s for 35 cycles, and 72˚C for 5 min. Reaction product of CB2 gene was normalized to GAPDH.

2.3. ELISA

The hPDL cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 per well and were allowed to attach for 12 h. The cells were then silenced with serum-free DMEM overnight. The cells were incubated with or without CB2-specific agonist HU-308 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (10−9, 10−8 and 10−7 M) for 6 h before further stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. In some experiments, the cells were pre-treated with CB2- specific antagonist SR144528 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (1 µM) for 2 h. At the end of the treatment, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in the culture media were measured using ELISA Kits (R & D System, Minneapolis, MN, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

2.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of OPG and RANKL

The hPDL cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 per well and were allowed to attach for 12 h. The cells were then silenced with serum-free DMEM overnight. The cells were incubated with or without HU-308 (10−9, 10−8 and 10−7 M) for 6 h before further stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. In some experiments, the cells were pre-treated with SR144528 (1 µM) for 2 h. To quantify the mRNA expression of OPG and RANKL, we performed quantitative real-time PCR using Prime-ScriptTM RT Reagent Kit Perfect Real-Time with a SYBR Green Reagent (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co. Ltd.) in the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System. The primer sequences and product sizes of each gene were adapted from Reference [18]. The cycling conditions were as follows: 95˚C for 30 s, followed by 95˚C for 5 s and 60˚C for 30 s for 40 cycles. Reaction products of both genes were normalized to GAPDH.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. All data were subjected to ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction for post hoc t-test. p-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

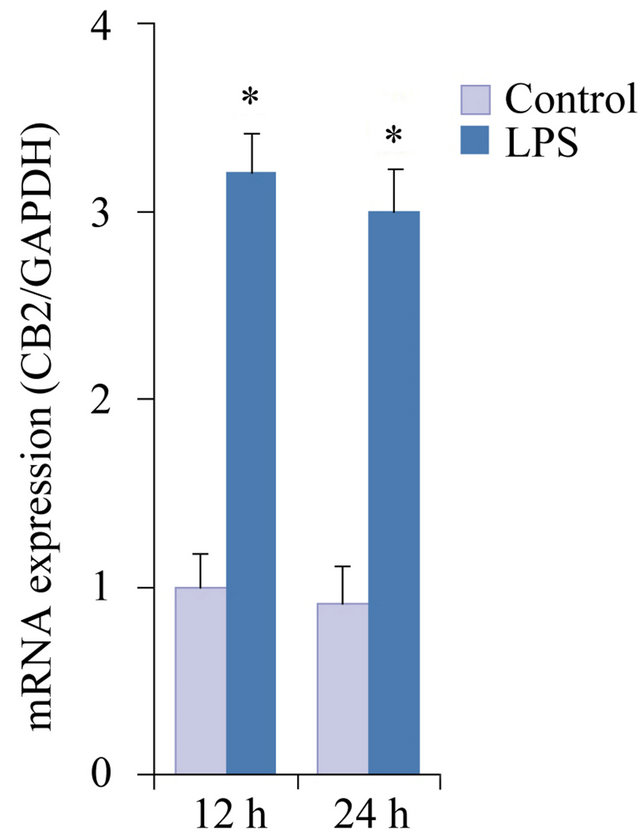

3.1. Expression of CB2 in hPDL Cells Exposed to LPS

Expression of CB2 in hPDL cells exposed to LPS was evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Exposure to LPS significantly increased CB2 mRNA expression after 12 h of treatment (p < 0.05; Figure 1). At 24 h, the level of CB2 mRNA expression in the LPS-stimu-

Figure 1. CB2 expression exposed to LPS in hPDL cells using quantitative real-time PCR analysis. The cells were stimulated with or without LPS (100 ng/ml) for 12 h and 24 h. The data were presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs the control group.

lated group was slightly reduced, but was still higher than that in the control group (p < 0.05; Figure 1).

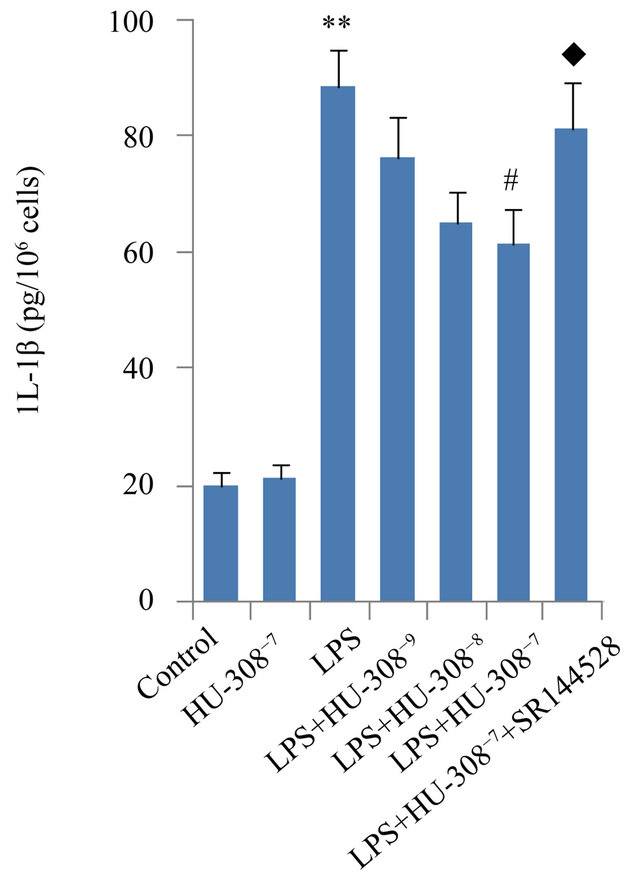

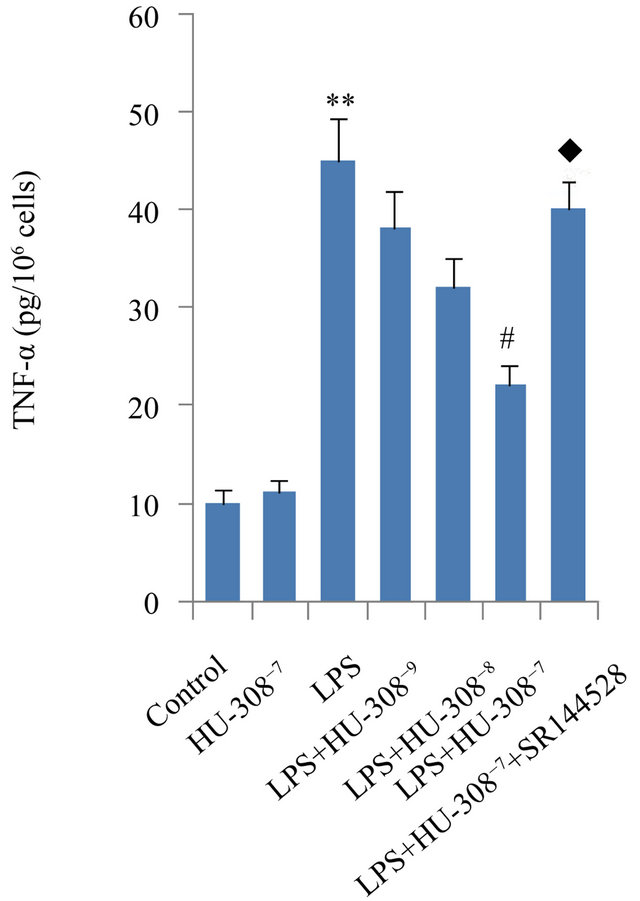

3.2. Effects of CB2 Activation and Inhibition on LPS-Induced Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Production in hPDL Cells

The effects of CB2 activation and inhibition on LPSinduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were assessed in hPDL cells by ELISA. Exposure to LPS for 24 h significantly increased the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (p < 0.01; Figure 2). The addition of HU-308 to activate CB2 at concentrations of 10−9, 10−8 and 10−7 M to the culture media dosedependently inhibited the stimulatory effects of LPS on pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. At 10−9 M, HU-308 only slightly suppressed the stimulatory effects of LPS, whereas 10−7 M of HU-308 significantly suppressed these effects (p < 0.05; Figure 2). Pre-treatment of hPDL cells with SR144528 to inhibit CB2 attenuated the effects of HU-308 on cytokine production (p < 0.05; Figure 2).

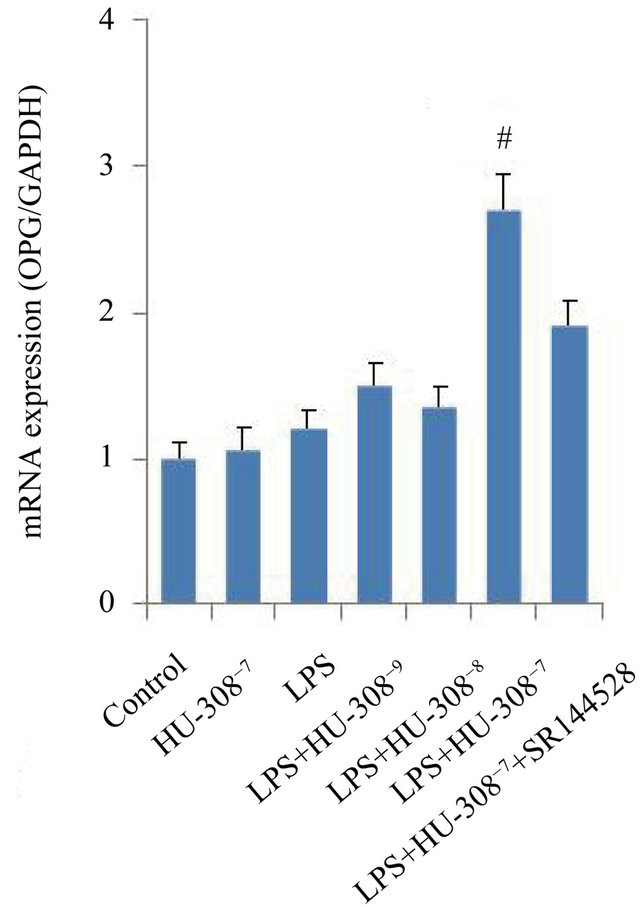

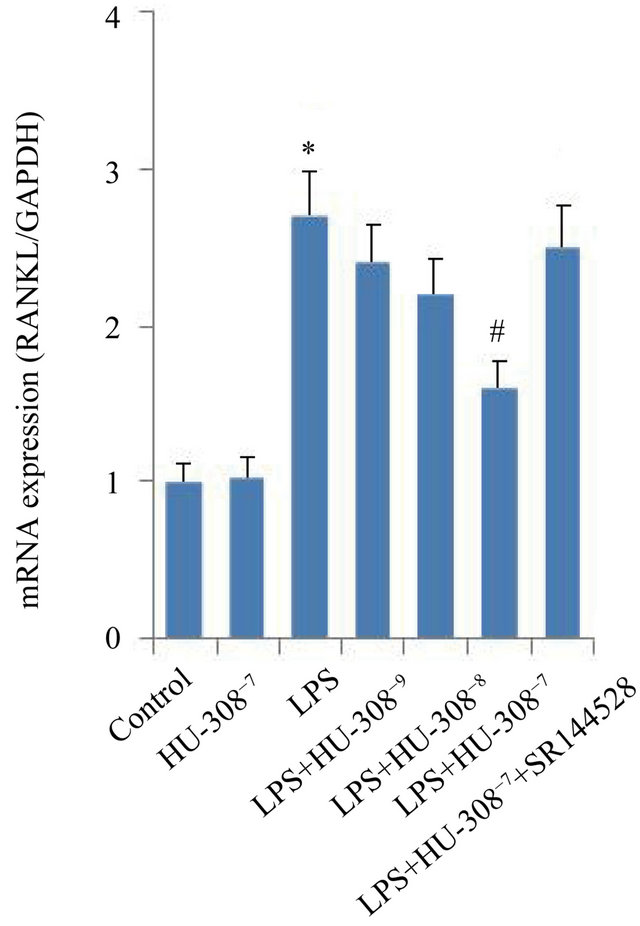

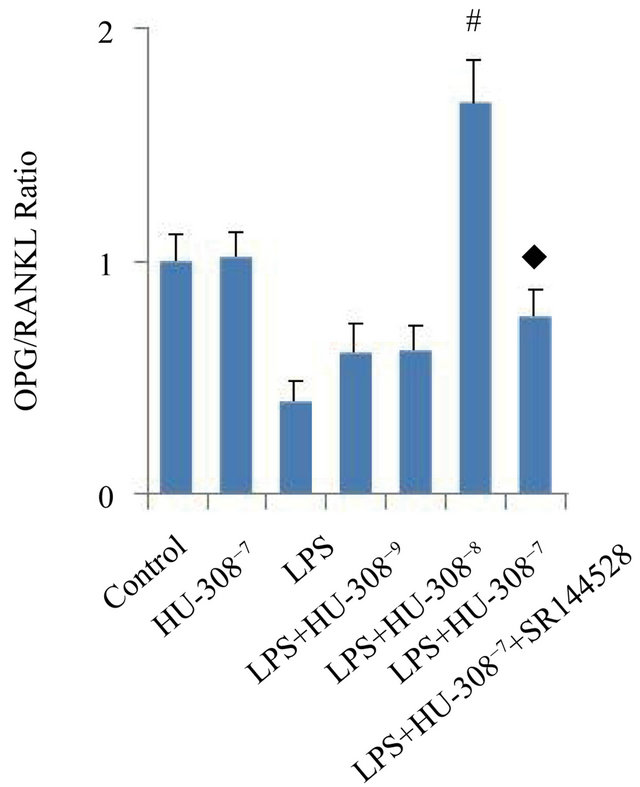

3.3. Effects of CB2 Activation and Inhibition on LPS-Induced OPG and RANKL Gene Expression in hPDL Cells

The effects of CB2 activation and inhibition on the mRNA expression of osteoclastogenic genes, OPG and RANKL, were investigated in hPDL cells. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis indicated that exposure to LPS for 24 h only slightly promoted OPG mRNA expression, however significantly increased RANKL mRNA expression (p < 0.05; Figures 3(a) and (b)). The addition of 10−7 M HU-308 to activate CB2 greatly enhanced the effect of LPS on OPG mRNA expression (p < 0.05; Figure 3(a)), whereas pre-treatment of hPDL cells with SR144528 to inhibit CB2 slightly attenuated this effect. The addition of HU-308 at concentrations of 10−9 to 10−7 M to the culture media dose-dependently inhibited the stimulatory effects of LPS on RANKL mRNA expression. 10−7 M HU-308 significantly decreased the stimulatory effect of LPS on RANKL mRNA expression (p < 0.05; Figure 3(b)). Pre-treatment of hPDL cells with SR144528 slightly attenuated this effect. As a consequence, the OPG/RANKL ratio, which is a predictor of osteoclastogenesis, decreased when exposed to LPS, furthermore increased significantly with the addition of 10−7 M HU-308 and finally decreased markedly after pre-treatment with SR144528 (p < 0.05; Figure 3(c)).

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we explored CB2 expression exposed to LPS and the regulatory effects of activation of CB2 on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine pro-

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c)

Figure 2. Effects of CB2 activation and inhibition on LPS-induced production of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in hPDL cells by ELISA. The cells were incubated with or without HU-308 (10−9, 10−8 and 10−7 M) for 6 h before further stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. In some experiments, the cells were pretreated with SR144528 (1 µM) for 2 h. (a) IL-1β; (b) IL-6; (c) TNF-α. The data were presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. **p < 0.01 vs the control group. #p < 0.05 vs the LPS-treated group. ◆p < 0.05 vs the LPS+HU-308 group.

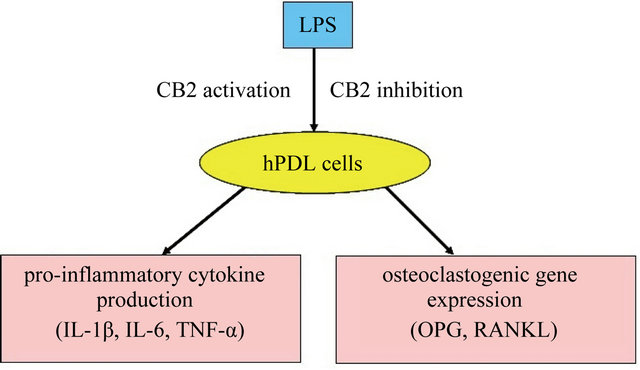

duction and osteoclastogenic gene expression in hPDL cells (Figure 4) for the first time.

The periodontium includes two kinds of fibroblasts: gingival fibroblasts and PDL cells [19]. Although the two cell types may exhibit distinct phenotypic characteristics [20,21], they both establish a dynamic balance between tissue formation and degradation at the tooth-bone inter face. Studies have suggested that PDL cells as well as gingival fibroblasts are involved in the inflammatory responses by producing cytokines and chemokines [22- 24]. Nakajima Y. et al. have found that human gingival fibroblasts exposed to LPS show significant up-regulation of CB2 expression [25]. Kozono S. et al. have observed up-regulation of the expression of CB2 localized

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c)

Figure 3. Effects of CB2 activation and inhibition on LPS-induced gene expression of OPG and RANKL in hPDL cells by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. The cells were incubated with or without HU-308 (10−9, 10−8 and 10−7 M) for 6 h before further stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. In some experiments, the cells were pretreated with SR144528 (1 µM) for 2 h. (a) OPG mRNA; (b) RANKL mRNA; (c) Ratio of OPG/RANKL. The data were presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs the control group. #p < 0.05 vs the LPS-treated group. ◆p < 0.05 vs the LPS+HU-308 group.

on fibroblasts and macrophage-like cells in granulation tissue during wound healing in a periodontal woundhealing model in rats [26]. In our previous study, we found that hPDL cells express CB2 [18]. Here we discovered that the inflammation promoter LPS markedly enhanced CB2 expression in hPDL cells. Since CB2 plays a crucial role in inflammatory responses and bone metabolism [12-17], we further explored the regulatory effects of activation of CB2 on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and osteoclastogenic gene expression in hPDL cells.

HU-308 is a synthetic, highly specific cannabinoid ligand for CB2 [27]. It has been reported that activation of CB2 by HU-308 stimulates osteogenic activity of osteoblasts and restrains osteoclast formation [16]. Our results showed that LPS significantly increased the production of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in hPDL cells, whereas HU-308 markedly suppressed LPS-induced cytokine

Figure 4. Schematic diagram: activation of CB2 regulates LPSinduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and osteoclastogenic gene expression in hPDL cells.

production. These pro-inflammatory cytokines are thought to cause inflammation in periodontitis [28,29]. IL-1β and TNF-α are pivotal cytokines in the context of periodontal disease [30,31], since they are expressed in higher levels in the gingival crevicular fluid and inflamed periodontal tissues of patients with a clinical disease compared with healthy people, and cause alveolar bone resorption [32, 33]. IL-6 promotes bone resorption and acts as a potent inducer of osteoclast formation in vitro [34]. Our study has suggested that activation of CB2 by cannibinoids, such as synthetic cannabinoids, may exhibit anti-inflammatory and anti-resorptive effects on LPS-stimulated hPDL cells.

Several studies have reported the effects of cannabinoids on inflammatory periodontal tissues. Nakajima Y. et al. have discovered that human gingival crevical fluid contains a detectable level of endocannabinoid anandamide (AEA). AEA significantly reduces the production of pro-inflammatory mediators IL-6, interleukin-8 (IL-8) and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS in human gingival fibroblasts [25]. Napimoga M.H. et al. have indicated that cannabidiol, a cannabinoid component from cannabis sativa, decreases pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β expression during experimental periodontitis in rats. [35] Recently, Ossola C.A. et al. have found that long-term treatment with topical synthetic cannabinoid methanandamide (Meth-AEA), applied daliy to gingival tissue of rats induced with periodontitis, reduced the production of some biological mediators of periodontal disease augmented by LPS, such as TNF-α, and significantly diminished the alveolar bone loss [36]. These reports and our study have indicated that cannabinoids have anti-inflammatory and anti-resorptive effects on inflammatory periodontal tissues.

It is accepted that OPG and RANKL are two essential osteoclastogenic genes in the regulation of osteoclastogenesis, and the ratio of OPG/RANKL determines the osteoclast differentiation and activation [37,38]. The hPDL cells express OPG and RANKL [4,5], suggesting that they may regulate osteoclastogenesis through the OPG/ RANKL system. Low ratios were observed in hPDL cells from resorbing deciduous teeth [39] and in periodontal tissue from patients with advanced periodontitis [40]. The OPG/RANKL system is involved in the regulation of bone metabolism in periodontitis. Interference with the system has a protective effect on osteoclastogenesis and bone loss in periodontitis [41,42]. Such interference may form the basis for rational drug therapy in periodontitis. Napimoga et al. have reported that cannabidiol, a cannabinoid component from cannabis sativa, decreases alveolar bone resorption by inhibiting RANK/ RANKL during experimental periodontitis in rats [35]. The inflammatory promoter LPS has been found to influence the expresson of OPG and RANKL in hPDL cells [43,44]. In our study, The OPG/RANKL ratio, which is a predictor of osteoclastogenesis, decreased when exposed to LPS, furthermore increased significantly with the addition of HU-308 and finally decreased markedly after pre-treatment with SR144528. Since the ratio of OPG/RANKL can be indicative for the role of hPDL cells in bone resorption or prevention of bone resorption [39,40], our results indicated the anti-resorptive effect of activation of CB2 on LPS-stimulated hPDL cells.

5. CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrated that activation of CB2 had antiinflammatory and anti-resorptive effects on LPS-stimulated hPDL cells. These findings suggest that activation of CB2 might be an effective therapeutic strategy for the treatment of inflammation and alveolar bone resorption in periodontitis. Our study provides a potential rationale for the use of exogenous factors such as CB2-specific agonists as drugs in the treatment of periodontitis. Further studies are required to corroborate the effect of CB2 activation on periodontitis in vivo.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30900285).

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Agarwal, S., Baran, C., Piesco, N.P., et al. (1995) Synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines by human gingival fibroblasts in response to lipopolysaccha rides and interleukin-1 beta. Journal of Periodontal Research, 30, 382- 389. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1995.tb01291.x

- Lekic, P. and McCulloch, C.A. (1996) Periodontal ligament cell population: The central role of fibroblasts in creating a unique tissue. Anatomical Record, 245, 327- 341. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199606)245:2<327::AID-AR15>3.3.CO;2-6

- Hou, L.T. and Yaeger, J.A. (1993) Cloning and characterization of human gingival and periodontal ligament fibroblasts. Journal of Periodontology, 64, 1209-1218. doi:10.1902/jop.1993.64.12.1209

- Wada, N., Maeda, H., Tanabe, K., et al. (2001) Periodontal ligament cells secrete the factor that inhibits osteoclastic differentiation and function: The factor is osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor. Journal of Periodontal Research, 36, 56-63. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.00604.x

- Kanzaki, H., Chiba, M., Shimizu, Y., et al. (2001) Dual regulation of osteoclast differentiation by periodontal ligament cells through RANKL stimulation and OPG inhibition. Journal of Dental Research, 80, 887-891. doi:10.1177/00220345010800030801

- Simonet, W.S., Lacey, D.L., Dunstan, C.R., et al. (1997) Osteoprotegerin: A novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell, 89, 309-319. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80209-3

- Yasuda, H., Shima, N., Nakagawa, N., et al. (1998) Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 95, 3597-3602. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597

- Lacey, D.L., Timms, E., Tan, H.L., et al. (1998) Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell, 93, 165-176. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81569-X

- Yasuda, H., Shima, N., Nakagawa, N., et al. (1998) Identity of osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor (OCIF) and osteoprotegerin (OPG): A mechanism by which OPG/ OCIF inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Endocrinology, 139, 1329-1337. doi:10.1210/en.139.3.1329

- Squitieri, F., Cannella, M., Sgarbi, G., et al. (2006) Severe ultrastructural mitochondrial changes in lymphoblasts homozygous for Huntington disease mutation. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 127, 217-220. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2005.09.010

- Klein, T.W., Newton, C., Larsen, K., et al. (2003) The cannabinoid system and immune modulation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 74, 486-496. doi:10.1189/jlb.0303101

- Klein, T.W., Friedman, H. and Specter, S. (1998) Marijuana, immunity and infection. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 83, 102-115. doi:10.1016/S0165-5728(97)00226-9

- Klein, T.W. (2005) Cannabinoid-based drugs as antiinflammatory therapeutics. Nature Reviews Immunology, 5, 400-401. doi:10.1038/nri1602

- Cabral, G.A. and Griffin-Thomas, L. (2009) Emerging role of the cannabinoid receptor CB2 in immune regulation: Therapeutic prospects for neuroinflammation. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine, 11, e3. doi:10.1017/S1462399409000957

- Bab, I. (2005) The skeleton: Stone bones and stoned heads? In: Mechoulam, R., Ed., Cannabinoids as Therapeutics. Milestones in Drug Therapy Series. Birkhäuser, Basel, 201-206. doi:10.1007/3-7643-7358-X_11

- Ofek, O., Karsak, M., Leclerc, N., et al. (2006) Peripheral cannabinoid receptor, CB2, regulates bone mass. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 103, 696-701. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504187103

- Scutt, A. and Williamson, E.M. (2007) Cannabinoids stimulate fibroblastic colony formation by bone marrow cells indirectly via CB2 receptors. Calcified Tissue International, 80, 50-59. doi:10.1007/s00223-006-0171-7

- Qian, H., Zhao, Y., Peng, Y., et al. (2010) Activation of cannabinoid receptor CB2 regulates osteogenic and osteoclastogenic gene expression in human periodontal ligament cells. Journal of Periodontal Research, 45, 504- 511.

- Giannopoulou, C. and Cimasoni, G. (1996) Functional characteristics of gingival and periodontal ligament fibroblasts. Journal of Dental Research, 75, 895-902. doi:10.1177/00220345960750030601

- Ivanovski, S., Li, H., Haase, H.R., et al. (2001) Expression of bone associated macromolecules by gingival and periodontal ligament fibroblasts. Journal of Periodontal Research, 36, 131-141. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.360301.x

- Somerman, M.J., Archer, S.Y., Imm, G.R., et al. (1988) A comparative study of human periodontal ligament cells and gingival fibroblasts in vitro. Journal of Dental Research, 67, 66-70. doi:10.1177/00220345880670011301

- Almasri, A., Wisithphrom, K., Windsor, L.J., et al. (2007) Nicotine and lipopolysaccharide affect cytokine expression from gingival fibroblasts. Journal of Periodontology, 78, 533-541. doi:10.1902/jop.2007.060296

- Jönsson, D., Nebel, D., Bratthall, G., et al. (2008) LPSinduced MCP-1 and IL-6 production is not reversed by oestrogen in human periodontal ligament cells. Archives of Oral Biology, 53, 896-902. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.05.001

- Palmqvist, P., Lundberg, P., Lundgren, I., et al. (2008) IL-1beta and TNF-alpha regulate IL-6-type cytokines in gingival fibroblasts. Journal of Dental Research, 87, 558- 563. doi:10.1177/154405910808700614

- Nakajima, Y., Furuichi, Y., Biswas, K.K., et al. (2006) Endocannabinoid, anandamide in gingival tissue regulates the periodontal inflammation through NF-kappaB pathway inhibition. FEBS Letters, 580, 613-619. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.046

- Kozono, S., Matsuyama, T., Biwasa, K.K., et al. (2010) Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in periodontal healing. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 394, 928-933. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.080

- Hanus, L., Breuer, A., Tchilibon, S., et al. (1999) HU-308: A specific agonist for CB (2), a peripheral cannabinoid receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 96, 14228-14233. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.25.14228

- Rizzo, A., Paolillo, R., Guida, L., et al. (2010) Effect of metronidazole and modulation of cytokine production on human periodontal ligament cells. International Immunopharmacology, 10, 744-750. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2010.04.004

- Jeong, G.S., Lee, S.H., Jeong, S.N., et al. (2009) Antiinflammatory effects of apigenin on nicotineand lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human periodontal ligament cells via heme oxygenase-1. International Immunopharmacology, 9, 1374-1380. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2009.08.015

- Chiang, C.Y., Kyritsis, G., Graves, D.T., et al. (1999) Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor activities partially account for calvarial bone resorption induced by local injection of lipopolysaccharide. Infection and Immunity, 67, 4231-4236.

- Gemmell, E., Marshall, R.I. and Seymour, G.J. (1997) Cytokines and prostaglandins in immune homeostasis and tissue destruction in periodontal disease. Periodontology, 14, 112-143. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00194.x

- Gamonal, J., Acevedo, A., Bascones, A., et al. (2000) Levels of interleukin-1 beta, -8, and -10 and RANTES in gingival crevicular fluid and cell populations in adult periodontitis patients and the effect of periodontal treatment. Journal of Periodontology, 71, 1535-1545. doi:10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1535

- Roberts, F.A., Hockett Jr., R.D, Bucy, R.P., et al. (1997) Quantitative assessment of inflammatory cytokine gene expression in chronic adult periodontitis. Oral Microbiology and Immunology, 12, 336-344. doi:10.1111/j.1399-302X.1997.tb00735.x

- Holt, S.C., Kesavalu, L., Walker, S., et al. (1999) Virulence factors of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Periodontology, 20, 168-238. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00162.x

- Napimoga, M.H., Benatti, B.B., Lima, F.O., et al. (2009) Cannabidiol decreases bone resorption by inhibiting RANK/RANKL expression and pro-inflammatory cytokines during experimental periodontitis in rats. International Immunopharmacology, 9, 216-222. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2008.11.010

- Ossola, C.A., Surkin, P.N., Pugnaloni, A., et al. (2012) Long-term treatment with methanandamide attenuates LPS-induced periodontitis in rats. Inflammation Research, 61, 941-948. doi:10.1007/s00011-012-0485-z

- Hofbauer, L.C., Khosla, S., Dunstan, C.R., et al. (2000) The roles of osteoprotegerin and osteoprotegerin ligand in the paracrine regulation of bone resorption. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 15, 2-12. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.2

- Crotti, T., Smith, M.D., Hirsch, R., et al. (2003) Receptor activator NF kappaB ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) protein expression in periodontitis. Journal of Periodontal Research, 38, 380-387. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.00615.x

- Fukushima, H., Kajiya, H., Takada, K., et al. (2003) Expression and role of RANKL in periodontal ligament cells during physiological root-resorption in human deciduous teeth. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 11, 346-352. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00051.x

- Liu, D., Xu, J.K., Figliomeni, L., et al. (2003) Expression of RANKL and OPG mRNA in periodontal disease: Possible involvement in bone destruction. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 11, 17-21.

- Han, X., Kawai, T. and Taubman, M.A. (2007) Interference with immune-cell-mediated bone resorption inperiodontal disease. Journal of Periodontology, 45, 76-94. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00215.x

- Jin, Q., Cirelli, J.A., Park, C.H., et al. (2007) RANKL inhibition through osteoprotegerin blocks bone loss in experimental periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology, 78, 1300-1308. doi:10.1902/jop.2007.070073

- Krajewski, A.C., Biessei, J., Kunze, M., et al. (2009) Influence of lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-6 on RANKL and OPG expression and release in human periodontal ligament cells. Acta Pathologica Microbiologica Scandinavica, 117, 746-754. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02532.x

- Shu, L., Guan, S.M., Fu, S.M., et al. (2008) Estrogen modulates cytokine expression in human periodontal ligament cells. Journal of Dental Research, 87, 142-147. doi:10.1177/154405910808700214

NOTES

*Corresponding author.

#These authors contributed equally to this work.