Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.4 No.3(2014), Article ID:43737,13 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2014.43024

Diversity and Scope of Senior Nurses’ Informal and Formal Experiences of Patient and Public Involvement in England

Markella Boudioni1, Susan McLaren2

1Institute for Leadership and Service Improvement, Faculty of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London, UK

2Faculty of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London, UK

Email: mboudioni@yahoo.co.uk, mclaresm@lsbu.ac.uk

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 25 December 2013; revised 18 February 2014; accepted 7 March 2014

ABSTRACT

Patient and public involvement (PPI) has been recognized internationally. In England, NHS policies have increasingly emphasized the importance of patient-centered services, but limited evidence exists about the implementation of PPI policies and strategies within organizations. Few studies have explored health professionals’ perceptions of PPI and comparatively little is known about the experience of senior nurses. A national consultation utilising three focus groups aimed to explore senior nurses’ PPI experience. Four Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs) and eleven Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in England, with fifteen senior nurses with leadership roles and direct PPI experience, participated. Focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim; anonymised transcripts were validated by participants and analysed with thematic analysis. Sixteen categories emerged within five sub-themes of PPI experience: provision of information and raising awareness (1 category), informal generic PPI-activities not perceived as PPI (3 categories), formal generic PPI (3 categories), involvement of specific groups (5 categories) and PPI in commissioning and strategy (4 categories). Findings provided new insights into senior nurses’ experiences and evidence that progress towards meaningful, effective PPI remains slow. Nurses performed PPI in a pragmatic sense, by virtue of the nature of nursing, but they did not recognise or label these activities as such. However, a plethora and variety of innovative activities formally recognised as patient and public involvement were undertaken, together with specific networks and groups’ involvement, and involvement linked to commissioning and strategy. Enhancing awareness of nurses through education, together with monitoring and feedback mechanisms could support the PPI implementation and effectiveness at organisations.

Keywords:Nursing; Patient and Public Involvement; Nurses’ Experiences; Focus Groups; Patient-Centred Care

1. Introduction

The value of patient and public involvement (PPI) and empowerment have been recognized and linked with patient experience and quality in health services internationally and in Europe [1] [2] . Countries have implemented a wide range of patient empowerment measures, including increasing patients’ involvement and participation in care decision-making in England [3] [4] . National Health Service (NHS) policies have increasingly emphasised patient-centred services and PPI for more than a decade in England. The legal duty to involve and consult the public [5] and the increasing body of international evidence for involving people in health care and its benefits [6] -[8] have been some of its drivers. The PPI agenda has permeated the World Class Commissioning vision, stating that “to be world class commissioners we need to know the needs and preferences of our local communities, work with our partners on the health and well-being agenda and work with local people to tackle health inequalities”. Specific emphasis was placed on “building continuous and meaningful engagement with patient and public to shape services”, as one of its competencies [9] . Furthermore, the “High Quality Care for All” [10] called for an NHS “that gives patients and the public more information and choice, works in partnership and has quality of care at its heart.”

Many definitions exist for involvement. “Patient involvement” (PI) refers to the active participation of patients/carers, as partners in their own care and treatment at various levels, i.e. health services planning, service delivery, quality monitoring, development [11] . Involve [12] summarised this as “everything that enables people to influence the decisions and get involved in the actions that affect their lives.” Patient and public involvement expands to public involvement; it is commonly used in England.

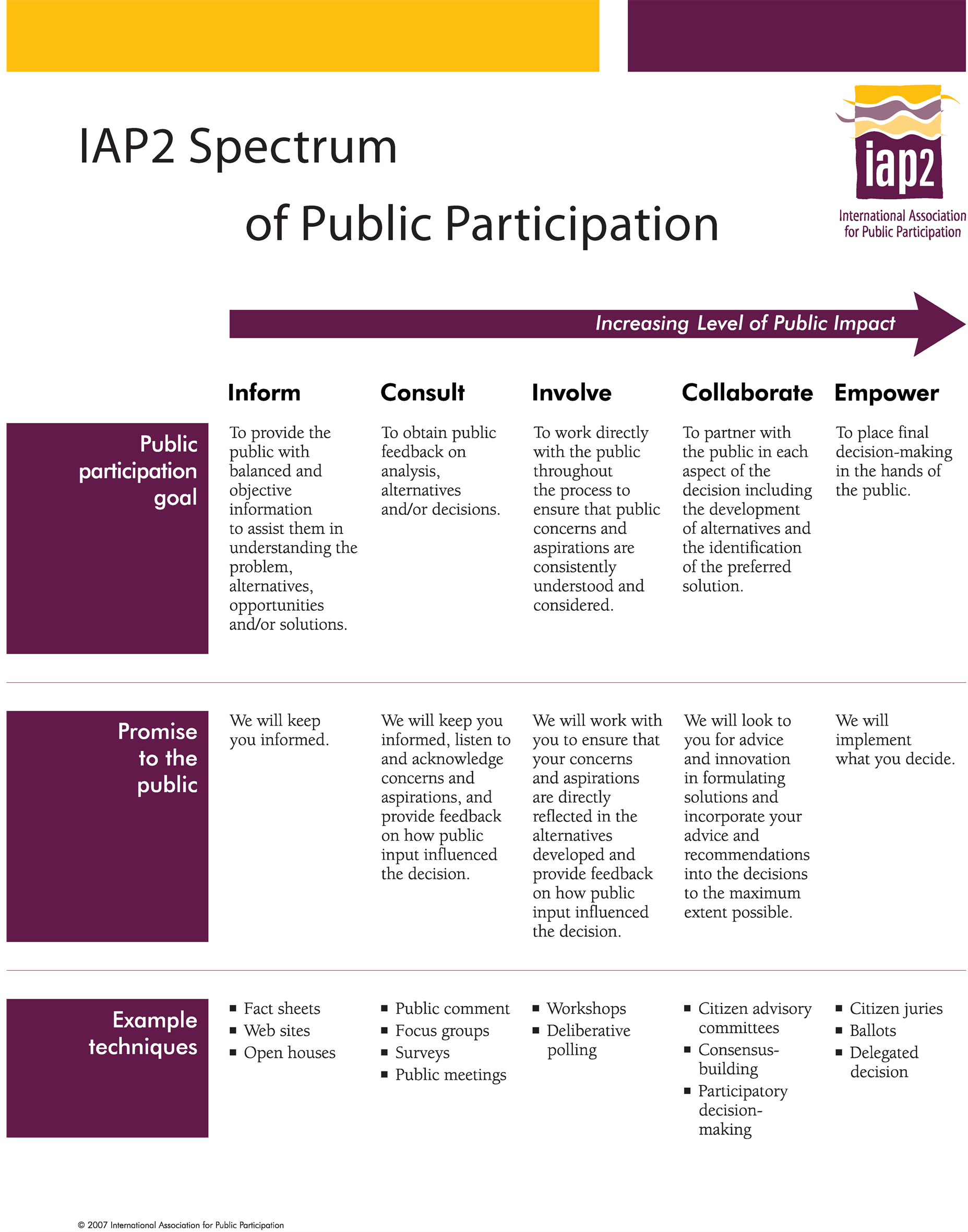

A number of typologies or models present different dimensions, levels, strategies, techniques or processes and their implications for the quality or depth of involvement, participation or empowerment. The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) proposes an advanced spectrum based on increasing levels of participation, providing a framework for analysing the scope and depth of public participation (Figure 1). At one end there is provision of information, and at the other end are individual contributions towards decision-making [13] .

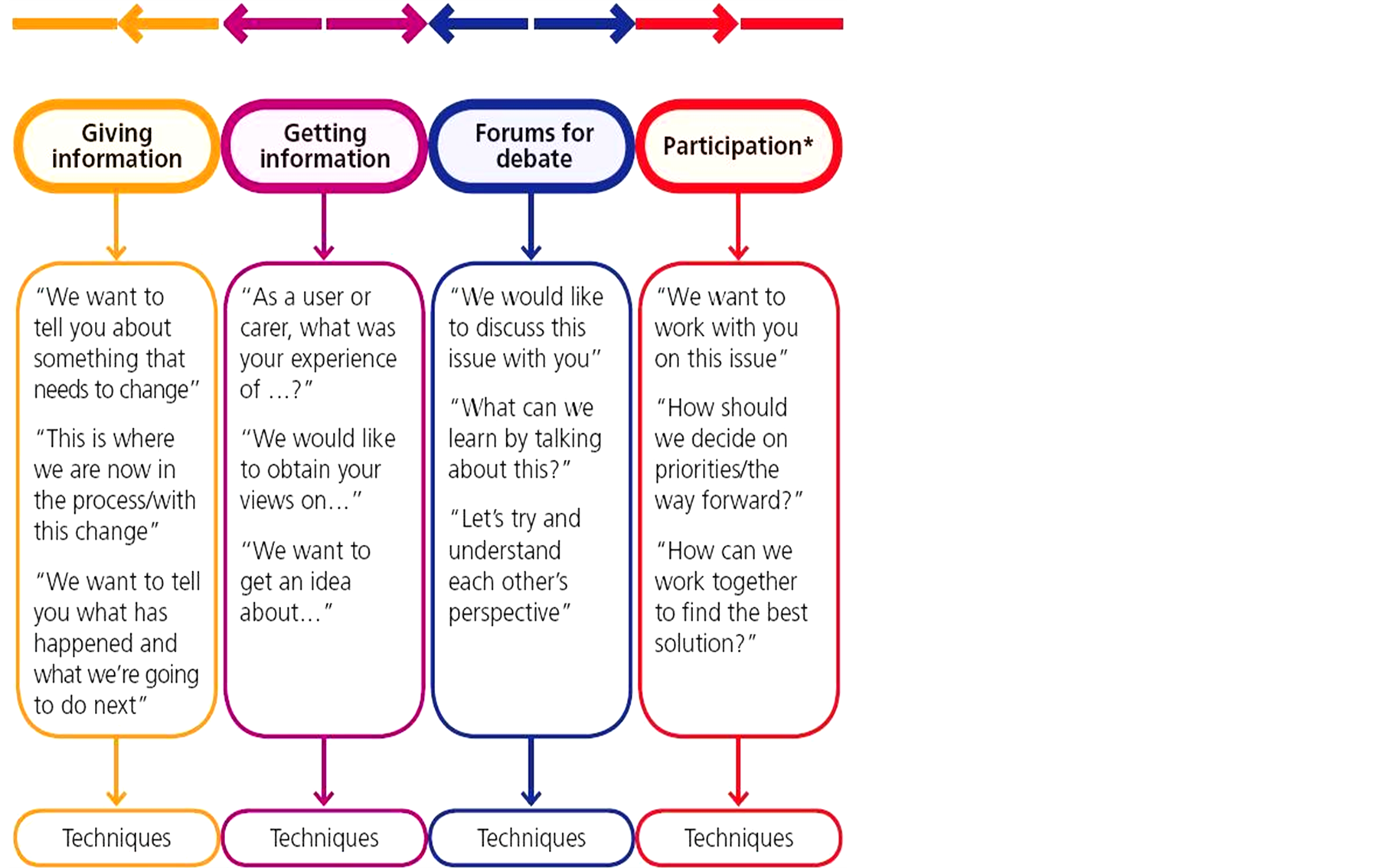

To enable policy implementation, the English NHS has adopted the “Involvement Continuum” [14] , encompassing giving and getting information, forums for debate and participation (Figure 2).

The research evidence for PPI varies in quality. However, benefits identified in systematic reviews have included improvements in health literacy, clinical decision making, self-care, chronic disease management and patient safety [15] [16] . Others have demonstrated improvements in the clarity of information provided and in patients’ knowledge [17] . However, limited evidence exists about the implementation of PPI policies and strategies within organisations [18] . National surveys have found that although health services were putting systems in place to involve people in planning and improving services, many organisational challenges remained [19] -[23] .

Health professionals’ perceptions and experiences of PPI have been explored inadequately. Only three studies have explored health professionals’ perceptions of PPI [24] -[26] showing that progress towards achieving meaningful and effective PPI was slow. Significant changes to the way that PCTs organised PPI in commissioning, indicated the start of a cultural shift [24] [26] . An ethnographic study [25] found that health professionals determined areas for service user participation, which covered a wide range of activities; understanding and practice relating to this varied according to professional ideologies and circumstances.

Comparatively little is known about senior nurses’ experiences of embedding PPI, although nurses’ positive PPI support has been noted [6] . Nurses are key NHS frontline staff in terms of direct patient care; they also hold key management positions which require an understanding of PPI and its policy implementation challenges. This article reports on a national consultation exercise commissioned by the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) to explore senior nurses’ experiences of PPI in England. Further details of the project can be found in the full report [27] and an article exploring challenges and facilitators for PPI [28] .

Figure 1. IAP2 spectrum of public participation.

2. Methods

A qualitative exploratory design utilising focus groups with senior nurses (nurses with leadership roles) across England, was employed. Focus groups have the advantage of making use of group dynamics to stimulate discus

Figure 2. The involvement continuum.

sion, gain insights and generate ideas to pursue a topic in greater depth. It is a useful technique for exploring values and beliefs about health, disease and systems; they are popular in health promotion and action research, organisational research and development [29] . Being relatively economic and gathering views of many in a relatively short space of time were additional reasons for choosing focus groups [30] .

Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs) in England were selected as the first points of contact, having the advantage of being able to access all Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) and a range of senior nurses across England. All nine SHAs were invited to send representatives to participate in focus groups. Letters informing and inviting senior nurse managers were sent directly from the RCN to Chief Executives for approval; they allocated a key stakeholder to co-ordinate and explore the feasibility of a focus group locally. Stakeholders invited senior nurse managers to participate voluntarily. Recruitment was very slow, although the Chief Executives and key stakeholders were reminded with second letters and follow-up phonecalls; reasons given were work overload and other priorities. All communication regarding recruitment and selection took place between June 2008 and October 2008. Ethical approval from a Trust or an external body was not required; the University Ethics Committee was informed for this national consultation.

All participants were given an information sheet and consented in writing to participation and digital recording of the focus group. Confidentiality was ensured and all participants were aware of their right to withdraw. A semi-structured topic guide was drafted in collaboration with RCN and used for all focus groups; they were facilitated by MB, an independent University researcher. They lasted between 80 and 120 minutes and took place in private meeting rooms at SHAs’ premises.

Digital recordings were transcribed verbatim by professional transcribers. Data was analysed manually by MB using the principles of thematic analysis, thus coding data line by line and forming codes, categories and themes [31] [32] . Transcripts were checked against recordings for reliability. Anonymised summaries of the individual focus groups findings were sent to participants of each group for participant validation. Two participants only responded citing no comments; one of them reinforced a suggestion already made in the group.

3. Results

Fifteen senior nurses, with leadership roles and direct PPI experience, employed in eleven PCTs from four SHAs participated. Participants, all RCN members with a variety of roles (Table 1), took part in three focus

Table 1. Professional roles of participants.

groups at north, west central and south England locations, conducted between September and October 2008.

Sixteen categories emerged within five sub-themes of PPI experience: provision of information and raising awareness (1 category), informal generic PPI, not perceived as PPI (3 categories), formal generic PPI (3 categories), involvement of specific groups (5 categories) and PPI in commissioning and strategy (4 categories).

3.1. Provision of Information and Raising Awareness

Participants in one group provided examples of many initiatives in information provision and raising awareness of health care, recognizing them as the first levels of the public being involved in their health care. Raising general awareness by getting people to have their blood pressure checked in a variety of locations, i.e. parish councils, working man’s clubs, local shops and supermarkets were achieved. Stalls in central locations of busy shopping centres providing information about getting medicines were also utilised. In addition, use of media was very common. TV and radio campaigns on “clean your hands”, magazines, regular columns and sections in local newspapers, the local authority, the councils, were examples given. Mystery shoppers were also discussed. In addition, health buses on their own or in partnership, i.e. with the BBC, were recognised as a mobile method of raising awareness usually for specific conditions, by distributing leaflets, doing blood pressure checks and screening for diabetes.

Health buses… But when the bus goes round you take out lots of leaflets, do park up somewhere, do blood pressure checks and screening for diabetes, anything… that you want to do really, whichever is your theme and usually try and marry it up and using national days where it’s awareness raising for, you know, smoking awareness, older person’s day, mental health day…

(FG3, P8, 1-22)

3.2. Informal Generic PPI—Not Perceived as PPI

Activities as a result or consequence of the nursing role, specific activities aiming to improve the patient experience, and others involving patients and the public were not always recognized formally as PPI.

3.2.1. Influence of the Nursing Role

Certain professional characteristics of nursing i.e. being caring, having rapport, communicating effectively and understanding patients, contributed to effective patient involvement.

I think all nurses recognise the different aspects of their job but I’m not so sure they’d label it PPI because we’ve given it the title PPI, they would say it’s communicating with our patients, it’s understanding our patients. I think they’re, you know, they do understand very much that patients are at the centre of their role…

(FG2, P1, p27, 39-43)

3.2.2. Improving Patients’ Experience

Participants recognised that patients and improving the patient experience were at the centre of the role of all nurses, including ward and senior nurses. Conducting service evaluations and taking actions based on these evaluations, being engaged with patient satisfaction surveys, were examples of this recognition and of actions to improve the patient experience. However, they suggested that ward nurses did not view them as related to patient involvement—perhaps because PPI was viewed as a formal activity, part of the NHS agenda.

I don’t think that nurses on the ward would necessarily see doing a patient satisfaction survey to enable them to improve the patient experience in that area as patient and public involvement. I don’t necessarily think that they would make that link because we’ve, the NHS as a whole are sort of seeing, as almost regulators and you will do this around patient or you will do that…

(FG2, P2, p7, 1-10)

3.2.3. Other Activities Not Recognised as PPI

Participants reported that general managerial staff, nurse managers and specialist nurses, i.e. leads for cancer, were aware of the PPI agenda. They continuously involved patients and good links with the community were integral to their role. These and other activities, i.e. involvement of community groups, changes based on complaints and incidents, and feedback from patients were again not labeled or recognised as PPI.

P1: …I think that people shape their practice based on the feedback… I think you made a point about feedback because they’re hearing it on a daily basis and therefore they find out that things aren’t working so they try a different way of doing it, you’re a bit more removed in some of the settings, as in doctor role.

P3: I think a lot of nurses respond and actually probably initiate changes within teams and things like that without actually identifying the sort of pathway, it’s sort of second nature and I think as nurses we’re not very good at actually identifying all the good stuff that we do do because we automatically kind of do it.

(FG1, p6, 27-43)

3.3. Formal Generic PPI

There were, however, other activities that were recognised as involvement activities by the participants. They fell into three categories: public involvement, service user involvement and patient and carer involvement.

3.3.1. Formal Public Involvement

Formal public involvement approaches experienced and discussed by participants included public engagement events and talks, good partnership working at the community level, patient and public panels, MORI polls and surveys for needs assessments, a variety of forums and user groups.

…we’ve had a long standing patient and public panel… and we had leaflets and we recruited people from all round the county and beyond, some of them, and libraries, community groups, councils, all sorts, parish councils, so a real trawl and we’ve got people from all round the county. Currently we’ve got 40 members… they like that interaction because it’s sharing knowledge which is working in partnership, they’ve actually moved up a notch in that involvement continuum, whereby they’re having their own meetings… chairing it themselves, we’re not present to say respond to the Foundation document and to, because they’ve realised that actually they’re more powerful in the collective. So it’s evolving to be much more partnership and forum led.

(FG2, P4, p11, 11-26)

Public involvement, in the form of a public consultation, in the development of a strategy in urgent care was another example.

…or urgent care would be another one where we’ve had I think it’s about 430 responses to our urgent care strategy, the majority of which are from the public.

(FG3, P2, 19-21)

3.3.2. Formal Service User Involvement

Although involvement in sexual health commissioning through interviews with service users was mentioned, it was felt that this was very difficult because of the stigma attached. Other important formal service user involvement routes that participants had experienced included important involvement of users in health panels and as Non-Executive members of boards.

…non-execs obviously they operate a sort of proxy public engagement and sort of scrutiny on some of the stuff we’re doing, the public viewpoint. When I visit various services I talk to the public about services. Have a health panel I go and take things to them from time to time. Overview and scrutiny, I take things to them… usually it’s a sounding board and then this desire to do something better as part of our strategic public engagement stream of work which we’re setting up…

(FG1, P1, p16, 3-11)

3.3.3. Formal Patient and Carer Involvement

Formal patient and carer involvement routes included discovery interviews with patients to uncover the meaning and patterns of events. Patient stories to support developments or changes, monthly patient or carer forums in wards, patient experience surveys, patient involvement in staff interviews, patient involvement in Essence of Care and working in partnership with carers were other examples of active involvement.

…each of our wards has a monthly patient or carer forum, so inpatients at the time are invited and their visitors are invited into a forum where we are just talking about, sometimes when there are things on the agenda to talk to them about. As I say something’s been picked up within the survey we particularly want to find something out about then we will do but if not then it’s their agenda really, about anything that they want to pick up…

(FG2, P1, p9, 42-48)

3.4. Involvement of Specific Groups

Participants reported significant involvement with specific networks and groups of patients, carers and service users, i.e. maternity services, children and young people, diabetes, cancer, end of life care.

3.4.1. Specific Networks

Networks organised by communities affected by a specific condition, i.e. a cancer network with the power of its groups dynamics, and a neonatal network with parents being trained and being given a person specification, were presented as good examples of involvement.

There are some networks where communities have organised themselves sort of sub groups, cancer’s a pretty good example of that where their view can be filtered through, my group said this and then that person’s going for the legitimacy of the group and they understand they’re there to represent that group…

(FG1, P5, p10, 29-35)

3.4.2. Maternity Services

The midwifery services liaison committees were given as an example of user-led committees, being proactive, asking questions and challenging providers. Another example was a reconfiguration of maternity services with public involvement perspective; it was highlighted that the public were extremely instrumental in all the terms and decisions.

…we’ve had a lot of involvement where we’ve had really big consultations out and we had a reconfiguration of maternity services across [the locality]… And certainly, the way that was handled from the public perspective and involvement perspective and “let’s listen to you” perspective, which was actually really strong because the public were extremely instrumental in all the terms and decisions that Darzi had sort of put forward…

(FG3, P3, p2, 27-36)

3.4.3. Children, Young People, and Their Parents

Numerous examples were given involving children, young people, their parents and carers and related bodies, i.e. Children’s Trust and Parents Forums in practice.

1) Children and Young People A Children’s Trust and a shadow Children’s Trust Board made up of young people and replicated in each of the districts, thus being a network speaking to the young people, were brought on as active examples in one group. Involvement of a children’s group in the design of a children’s hospital, by using Play Train, a recognised type of playgroup, including play days and activities for children through the schools, was another active example discussed in another group. This involved a graphic designer using the children’s pictures and translating them into the hospital design. The children also created their own booklet for children coming into hospital and they did work about food. In addition, they created a video, the Eye View Project, with role playing; this was used as a teaching aid.

Another focus group reported service development within a children’s school environment through drawing and stories. Within the same group, another example was the implementation of the “here by rights standard” of engagement with young people. Furthermore, more advanced involvement was discussed, where young people completed a peer training programme and were educated to do peer-consultation within the Youth Service guidelines.

…Working with the Youth Service, they have a peer training programme, which is up about six weeks… the young people have to be CRB checked and all the rest of it but then they will go out and maybe speak to young people who are perhaps a year or two years younger than them and they will get very honest answers, way more honest than we might get and that is, it’s good, nationally recognised way of working, if you do it within the Youth Service guidelines.

(FG1, P3, p13, 10-21)

2) Parents and Carers of Children and Young People Sure Start was referred to as a good method of working with young parents, offering training and support to them, so they were able to contribute and understand their role on committees. A project that parents were involved in another group was the development of child health clinics attached to GP surgeries. Parents were consulted on their development; many difficulties, however, were highlighted with the senior management, the GPs and agreement on the plans.

…we did something very similar with the child health clinics that were attached to GP surgeries and we went to the parents and said “…what do you think of putting the child health clinic in the children’s centre?”, which had an area probably the size of this room, half of it was like a waiting area and half of it was a beautiful play area that you’d get in, probably a good nursery or a reception class of the school… The difficulty was actually getting senior management to agree to it, even though the parents were saying this is what we want and it’s the right way to go… the GPs didn’t want us to move out and the power of the GPs in influencing that…

(FG2, P5, p15, 43-51 and p16, 1-4)

3) Children, Young People, and Their Parents Specific projects on development of services, involving children or young people and their parents were other active examples discussed. A project involving young people and their parents to set up an outreach sexual health service revealed inconsistencies between what professionals thought young people wanted and what they actually wanted.

…we were setting up an outreach sexual health service, we did a focused piece of work with the community, for parents with the young people, and quite interestingly we had an open evening, where we had GPs saying ‘they all want to come to us for sexual health advice’ and the young people are going “no, we don’t” and the GPs saying “you’re wrong, you do” and the kids are going “no, we don’t”… we’ve empowered professionals to lead service development but actually they don’t always know even with the best will in the world what it is that actually will be accessed and what people want.

(FG1, P3, p11, 33-44)

Focus groups in palliative care with youth groups and parent groups of active kids who actively attended and also recently bereaved in hospices was another example; they were brought together in order to discuss, understand and take actions around palliative care and bereavement. A Parent Forum and children, through Sure Start, were involved in obesity issues in an innovative and collaborative way. Parents organised publicity with a local DJ and a walk; the children organised the launch of an obesity campaign. The whole event was perceived as “messy” but fun for the children. This involvement brought changes to service provision, i.e. following this, walks were ongoingly organised at half-terms.

3.4.4. Diabetes

Two examples were given with involvement in diabetes. The first was about patients and public being involved in developing fundamental principles for diabetes care. The second one was about a user group leading in the development of a diabetic unit with a number of activities.

There’s also a user group in the diabetes, in the unit, which is totally user led, they call their own meetings, they have their own suggestion box in the atrium, they invite members of staff into their regular quarterly meetings and require the staff to respond back.

(FG2, P4, p11, 27-30)

3.4.5. Involvement of Other Groups

Involvement of specific subgroups of patients was demonstrated in cancer; patients were involved in services’ internal design and décor, a follow-up involvement at ITU and focus groups around the end of care.

…we’ve done some focus groups around end of life which of course is notoriously difficult because the people you’re talking to are usually the carers because… the recipients of end of life services are normally dead by the time you’re talking about them, not saying you can’t get their views as you’re going through services but ran a focus group and it’s carers that we get there. But we have done that to help shape our end of life strategy…

(FG1, P1, p16, 11-17)

3.5. PPI in Commissioning and Strategy

PPI in commissioning included involvement of people in strategic discussions, taking on board service users’ views and shaping the services accordingly. PPI experiences in commissioning and strategy were demonstrated in various ways, i.e. a general context, improving specific services, involvement in strategic boards and committees, and practice-based commissioning.

3.5.1. General PPI in Commissioning and Strategy

A participant mentioned a patient and public involvement toolkit that one of the SHAs had launched on world class commissioning. However, at the time of the study, discussions were taking place and this was not yet implemented. Other participants in the same focus group said that themes that came out of big PPI consultations and conversations had been used to develop the PCT priorities for commissioning. Another referred to working in partnership with local groups and organisations as an element of the commissioning process.

…what is springing up is lots of partnerships, you know, you’ve got old people’s partnerships, local groups within communities, which are based around the council and ward groups where you need to get involved. The Education and the Young People’s Forums, the Young People’s Carers, Young People’s Parliament, so you’re actually looking at lots of different areas and ways… So that element is still firmly within our commissioning process and it is actually very time consuming and takes a great deal of effort but it’s very rewarding as well.

(FG3, P4, p4, 20-30)

Although many large scale consultations about commissioning, i.e. relevant to Darzi’s report [10] , were recognised as having taken place, another participant expressed concerns about the need of small consultations, awareness and education events and feedback sessions with patients. A PPI strategy and teams working in PPI within a SHA-involving three PCTs were also recognised.

We’ve got a small team in communications and public patient involvement. We’ve got a signed off engagement strategy… And we’ve got, within that team a number of individuals who can go to Overview and Scrutiny, who can run focus groups, who know what the local population needs, because obviously we’re three PCTs with very different health sort of needs and communities, who know the local communities and that’s essential.

(FG3, P2, p31, 43-50)

3.5.2. Improving Services

The need for patient and public involvement in developing services as part of a wider community impact was highlighted, i.e. in moving hospitals, closing down wards. PPI in improving and changing specific services, i.e. discharge, was also discussed. A series of focus groups took place over a year with regular meetings; people from the communities, the PCT and social care were involved and they came up with 10 recommendations about discharge services that were reported to the Chief Executive. Although it had taken three or four years to review those recommendations and timeframes, a few of them had been taken onboard to improve the discharge process across the whole system.

…they did a big, a lot of work on discharge, a focus group, from the panel a few years ago. And I think the challenge in the NHS is the timeframes, actually, because what happened was the whole focus group lasted about a year of regular and regularly meetings, calling in people from the communities and the PCT from social care, listening to what was happening now, so that they actually understood the ins and outs of the service and they came up with 10 recommendations… they haven’t implemented all the recommendations but certainly quite a few of them have been taken onboard to improve the discharge process across the whole system…

(FG2, P4, p12, 31-40)

3.5.3. Strategic Boards and Committees

Involving members of the public in the Board of Governors was another public involvement activity in commissioning. Lay members participated in meetings and had potential input into strategies. However, it was recognised that their actual involvement varied, i.e. some members did not feel comfortable or able to participate, because of lack of confidence or power dynamics. The level of involvement was also linked with the Trust status, i.e. Foundation status.

…certainly we’ve got a lot more on the community approach in that we’ve got three members of the public on the Board of Governors. So most people have potential, have quite a lot of input into sort of the strategy that the Foundation takes and obviously we are accountable to the public in the area that we serve by nature of being a Foundation Trust, so we’ve done quite a lot of work around that, so I think that the Foundation status may have implications over sort of where PPI goes…

(FG2, P6, p4, 25-32)

Adopting more proactive, innovative general approaches, and running boards in different ways, as resulted from involvement of patients, were other positive examples. These included going out to the public rather than expecting them to come into the organisation, having formal board meetings, and then “stakeholder finding” (travelling to localities) or discussing themed topics with the public in other localities, i.e. hand washing for infection control, the role of the Community Matron, Choose and Book, procurement.

P1: Or out into [a locality], into [another locality] and we had themed topics. And we were very careful that we would do 10 minutes formal presentation on two topics but then it was about listening to members of the public and getting them to help us shape our priorities.

I: Could you give me an example of these topics?

P1: Yes, hand washing for infection control, the role of the Community Matron, Choose and Book, what does that mean to you? Some of the examples.

P4: I think procurement’s been massive as well…

(FG3, p6, 3-14)

A participant reported a negative experience of recruiting patient members to a healthcare association infection control committee. The terms of reference for two operational groups, under the infection control committee, included having a patient member, but for 15 months they were not able to attract patient members through PALS and LINKs.

3.5.4. Practice-Based Commissioning

Within the practice-based commissioning area, having frank conversations, strong partnerships and managing expectations in relation to budgets were considered the ways forward. It was recognised, however, that involvement was still tokenistic in occasions; a negative example was given, when the practice-based commissioning group was considering taking certain actions and involving the public following these actions. On the other hand, many positive initiatives were taken, i.e. accrediting GPs with a specialist interest, having lay assessors on a panel, inviting many stakeholders from the community/voluntary sector in GP stakeholder events.

…we try to engage the public in a lot of commissioning processes that we’re doing at the moment, for instance accrediting GPs with a specialist interest, we have lay assessors on a panel to give the patients an overview and we let the patients walk, they walk through the surgery to see what it’s like from the patient’s perspective. …on interview panels for GP appraisers.

(FG3, P1, p9, 25-30)

4. Discussion

The consultation exercise yielded valuable insights into the evolving process of implementing PPI in NHS Trusts in England from a senior nursing perspective. However, some limitations should be borne in mind. Recruitment of focus groups representing nine SHAs proved challenging due to potential participants’ workloads. The findings are based on three focus groups only, and fifteen self-selected participants representing four SHAs and eleven organizations, which cannot preclude bias and limits generalizability. Furthermore, participants were all in strategic senior management positions; thus their experiences are not necessarily representative of a wider nursing PPI experience. This consultation was conducted in late 2008. However, since then guidelines for PPI implementation have not yet been issued in England and no studies exploring senior nurses’ experiences of PPI have been published. Notwithstanding the limitations, the focus groups produced rich data and shed light on a variety of PPI experiences.

This consultation found that a variety and plethora of formal and informal PPI activities were reported by senior nurse managers, although not all were directly engaged in such activities or in applying them to the development of commissioning. However, as a consequence of their nursing roles and responsibilities, many participants involved patients and the public in their care and treatment, in some instances performing PPI in its pragmatic sense, but not recognizing such activities as formal PPI. So, although it could be argued that nursing activities are involving and empowering with regard to PPI, it raises the question as to how such activities are recognized and valued. Lack of clarity existed as to whether PPI was part of participants’ clinical responsibilities, and how they should demonstrate that they were engaged in the process. Nonetheless, an important finding of this consultation was that achievements were demonstrated in the implementation of PPI, which have not been recognized, shared and systemized within practice. Public consultations, event and talks; involvement of users in health panels, as non-executive members of boards; discovery interviews with patients, patient stories to support development of services, patient or carer forums, patient experience surveys, patient involvement in staff interviews and Essence of Care, working in partnership with carers were all achievements formally recognised. Many examples involving specific groups of patients, carers and service users, were also recognised and cited, i.e. maternity services, children and young people, diabetes, cancer, and end of life care.

At a commissioning level, some achievements were also demonstrated, i.e. the development of a world class commissioning PPI toolkit, PPI consultations being used for commissioning priorities, PPI involvement in shaping discharge services. Having lay assessors on GP panels, inviting lay stakeholders in GP stakeholders events were achievements in practice-based commissioning. Nonetheless, findings suggested that reinforcement could be needed in organizational and strategic structures, since in some instances PPI remained tokenistic, especially at the strategic, decision making level. Limited evidence was also given of developing “patient-focused” proposals; or in setting the priorities and plans that are the substance of commissioning strategies. In commissioning, openness and realism are needed as to what the NHS can and cannot do and why. To achieve world class commissioning competencies [9] a focus is needed “on the who, what, where and when”, a strategy, an action plan and perhaps extra resources to deliver the world class commissioning competencies.

The most recent PCT survey (2009) reported significant changes to the way that PCTs organised patient and public engagement in commissioning, marking the beginning of a cultural shift [26] . The Healthcare Commission study (2009) identified that health services’ staff are often the most important change drivers for PPI. Committed senior managers and clinicians play a vital role in creating “responsive” NHS healthcare organisations. A recommendation was strengthening the culture of being open and responsive to local people, asking people how their health services can serve them better, and acting on their responses through strong management and clinical leadership [23] . This consultation has identified many formal and informal PPI activities, involvement of specific groups and PPI in commissioning and strategy that may indicate a cultural shift towards patient and public involvement, with nurses playing a pivotal role.

An earlier paper arising from this consultation reported PPI challenges and facilitators. Professional cultures, communication, attitudes of health professionals together with provision of active support for patient engagement were identified as problematic [27] [28] [33] [34] . Important facilitators corresponded to some world class commissioning priorities [9] [27] [28] . Specifically, participants discussed services based on patient experience; work with community partners and engagement with public and patients; all of which were highlighted within the world class commissioning vision associated competencies in England. Similar issues have also been identified in national and international policies elsewhere [2] -[4] .

5. Conclusions

With regard to senior nurses’ PPI experiences, this consultation constitutes one of the first to explore their contribution to “an emerging productive partnership” [18] . Findings reinforced the value of nursing in a sustainable modern healthcare system, especially through effective collaboration with patients and the wider public. Notwithstanding its limitations, rich qualitative data shed light on the diversity and scope of PPI as experienced by senior nurses in management positions, an under-researched area. Of particular interest was the finding that nurses performed patient involvement in a pragmatic sense. Many activities were linked to involvement, but were not formally recognised as such. Also of interest is the plethora and diversity of activities formally recognised as PPI.

International and national policies elsewhere [2] -[4] , and NHS policies in England [5] -[10] [14] , place a great emphasis on patient involvement. However, these findings suggest that although positive progress has been made, recognition of involvement activities and PPI experiences of senior nurses are variable. Some activities are not recognised as PPI, and effective monitoring is needed for involvement activities at various levels, i.e. individual care, treatment and commissioning. Enhancing nurses’ awareness and understanding through education about the PPI nature and purpose, together with the development and introduction of appropriate PPI monitoring and feedback mechanisms, could support both organizational implementation and effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants—senior nurses, for giving up their time to take part in this consultation. We would also like to thank Professor David Sines for his support, the late Professor Bob Sang for his initial contribution and his comments on the project, and Dr Sophie Staniszewska for her comments on the final report. Ms Helen Caulfield, RCN Policy Department, negotiated access within NHS organisations to enable focus groups to be conducted.

References

- World Health Organisation (1986) Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. The Move towards a New Public Health. WHO, Ottawa.

- World Health Organisation (1997) The Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century. 4th International Conference on Health Promotion. WHO, Jakarta. www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/jakara_declaration_en.pdf.

- World Health Organisation (2009) The European Health Report 2009: Health and Health Systems. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen.

- Fallberg, L. and Mackenney, S. (2004) Conclusion. In: Mackenney, S. and Fallberg, L., Eds., Protecting Patients’ Rights? A Comparative Study of the Ombudsman in Healthcare, Radcliffe, Oxon.

- Department of Health (2003) Strengthening Accountability: Involving Patients and the Public. DH, London.

- Department of Health (Farrell, C.) (2004) Patient and Public Involvement in Health: The Evidence for Policy Implementation. DH, London.

- Department of Health (2004) “Getting over the Wall” How the NHS Is Improving the Patients’ Experience. DH, London.

- Department of Health (2010) Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. The Stationary Office, London.

- Department of Health (2007) World Class Commissioning: Vision Summary. DH, London.

- Department of Health (2008) High Quality Care for All: NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. DH, London.

- Kelson, M. (1997) User Involvement: A Guide for Developing Effective User Involvement Strategies in the NHS. College of Health, London.

- Involve (2005). People & Participation: How to Put Citizens at the Heart of Decision-Making. Involve, London. http://www.involve.org.uk/

- International Association for Public Participation (2007) The Spectrum of Public Participation. http://www.iap2.org/associations/4748/files/IAP2%20Spectrum_vertical.pdf.

- Department of Health (2008) Real Involvement: Working with People to Improve Services. DH, London.

- Coulter, A. and Ellins, J. (2006) Patient Focused Interventions: A Review of Evidence. Quest for Quality and Improved Performance (QQUIP). The Health Foundation, London.

- Coulter, A. and Ellins, J. (2007) Effectiveness of Strategies for Informing, Educating and Involving Patients. British Medical Journal, 335, 24-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80

- Nilsen, E.S., Johansen, M., Oliver, S. and Oxman, A.D. (2010) Methodological Considerations Involved in Developing Healthcare Policy and Research, Clinical Practice Guidelines and Patient Information Material. Cochrane Collaboration, John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey.

- Sang, B. (2009) Chapter 22. User Involvement: The Involved and Involving Community Health Care Nurse. In: Sines D., Saunders, M. and Forbes-Burford, J., Eds., Community Health Care Nursing, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, 352-362.

- National Centre for Involvement (2007) A Baseline Assessment of the Current State of Patient and Public Involvement in English NHS Trusts. NCI, Warwick.

- National Centre for Involvement (2008) The Current State of Patient and Public Involvement in NHS Trusts across England; Findings of the National Survey Full Report. NCI, Warwick.

- Picker Institute Europe (2007) Patient and Public Involvement in Primary Care Commissioning. Picker Institute Europe, Oxford.

- National Audit Office (2007) Improving Quality and Safety Progress in Implementing Clinical Governance in Primary Care: Lessons for the New Primary Care Trusts. The Stationery Office, London.

- Healthcare Commission (2009) Listening, Learning, Working Together? A National Study of How Well Healthcare Organisations Engage Local People in Planning and Improving their Services. Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, London.

- Chishold, A., Redding, D., Cross, P. and Coulter, A. (2007) Patient and Public Involvement in PCT Commissioning: A Survey of Primary Care Trusts. Picker Institute Europe, Oxford.

- Fudge, N., Wolfe, C.D.A. and McKevitt, C. (2008) Assessing the Promise of User Involvement in Health Service Development: Ethnographic Study. British Medical Journal, 336, 313-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39456.552257.BE

- Picker Institute Europe (2009) Patient and Public Engagement. The Early Impact of World Class Commissioning: A Survey of Primary Care Trusts. Picker Institute Europe, Oxford.

- Boudioni, M. and McLaren, S. (2009) Nurses and Patient and Public Involvement: A Consultation in Four Strategic Health Authorities in England. London South Bank University, London.

- Boudioni, M. and McLaren, S. (2013) Challenges and Facilitators for Patient and Public Involvement in England; Focus Groups with Senior Nurses. Open Journal of Nursing, 3, 472-480. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2013.37064

- Barbour, R.S. and Kitzinger, J. (1998) Developing Focus Group Research: Politics, Theory and Practice. Sage, London.

- Darlington, Y. and Scott, D. (2002) Qualitative Research in Practice: Stories from the Field. Open University Press, Buckingham.

- Boyatzis, R.E. (1998) Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Sage, London.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77- 101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Richards, N. and Coulter, A. (2007) Is the NHS Becoming More Patient-Centred? Trends from the National Surveys of NHS Patients in England 2002-2007. Picker Institute, Oxford.

- Coulter, A. and Magee, H. (2004) United Kingdom. The European Patient of the Future. Open University Press, Berkshire.