Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.2 No.2(2012), Article ID:20434,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.22013

Attitude survey of nursing students in Madagascar and Japan

![]()

1School of Health Sciences, Hirosaki University, Hirosaki, Japan

2Joseph Ravoahangy Andrianavalona University Hospital, Antananarivo, Madagascar

Email: yamabe@cc.hirosaki-u.ac.jp

Received 1 December 2011; revised 30 January 2012; accepted 20 February 2012

Keywords: Madagascar; Japan; nursing student; image to nurse

ABSTRACT

Background: Few investigations have focused on nursing students from a developing country in relation to a developed country like Japan. Objective: This study explored differences between the nursing students in Madagascar and Japan. Subjects and Methods: This is a prospective analytical study of 63 nursing students—32 Japanese and 31 Malagasy. Questionnaires were distributed to students in Madagascar and Japan in 2010 and collected for statistical analysis. Results: Malagasy students tended to think that nursing plays a psychological role, and they have positive view for this function. In contrast, Japanese students tended to think that nursing is physical work and they make a point of its outcome and the need for social and economic guarantees. Conclusion: The nursing students in Madagascar and Japan expressed different views and goals. While several factors may be involved in these differences, their distinct medical situations are most likely the major contributor.

1. INTRODUCTION

The essence of nursing is common even in different medical situations, while how nursing is viewed might vary in some ways. Understanding the differences in the ways of thinking about nursing may improve the cooperation on the medical scene between developing and developed countries. One of the authors met a Madagascar medical student in Japan, who visited Japan for study and training in 2008. The author was interested in Madagascar through having a friendship with the medical student. This study therefore explored possible differences in nursing between Madagascar and Japan through surveys of nursing students. The developing country of Madagascar is an island southeast of Africa in the Indian Ocean. Its life expectancy at birth is 65 years, and its total expenditure on healthcare as a percentage of private expenditures is 4.1. The infant mortality rate before the age of 1 year is 43 per 1000 live births, and the maternal mortality rate is 440 per 100,000 live births [1]. In Madagascar, deaths due to infectious diseases such as malaria [2] and tuberculosis still exist to this day [3].

On the other hand, the developed country of Japan is an island located west of the Eurasian continent in the Pacific Ocean. Its life expectancy at birth is 83 years (2009 data), and its total expenditure on healthcare as a percentage of private expenditures is 8.3. The infant mortality rate before the age of 1 year is 2 per 1000 live births, and the maternal mortality is 6 per 100,000 live births [4]. In Japan, deaths due to diseases related to lifestyle such as cancer, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and diabetes are rising [5], but deaths due to tuberculosis have declined as the food and the state of hygiene has improved since World War II [6].

A different medical situation affects the way of thinking on nursing. The aim of this study is to compare the nursing students in Madagascar and Japan in order to know any difference.

2. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This study included 63 nursing students: 32 Japanese and 31 Malagasy. In Madagascar, 1st to 3rd year students from a private institute and the Institute of Inter-Regional Training of Paramedics in Antananarivo (IFIRP) participated in this study. Questionnaires were given to these students in June 2010 and collected in November 2010. Nursing courses are taught in the 3rd year and students attend practical training in several hospitals and healthcare centers within the country (clinics, hospital bases, maternity or birthing clinics, private clinics, or university hospitals). Students must pass a test in order to enroll in nursing courses and to graduate, but no test is need for national qualifications.

In Japan, 4th year nursing students from the Nursing Department at Hirosaki University School of Health Sciences participated in this study. Questionnaires were distributed to participants in July 2010 and collected at the end of August, when students finished their training in hospitals. They mainly practice in hospitals affiliated with Hirosaki University starting in August of the 2nd year until July of the 4th year. The nursing program is for four years, and students obtain a national nursing diploma after passing the national examination. Hirosaki University Hospital is a specific function hospital that provides high medical care and performs research, education and training.

The questionnaires were made by ourselves and consisted of six questions, in addition to participant background parameters (i.e., age, sex, religion, marriage status, and children status). The questions are as follows: Q1. Why do you want to become a nurse? Q2. What kind of nurse do you want to be in the future? Q3. What roles do nurses in your country play? Q4. What actions make you feel that you are a nurse when you practice in the hospital? Q5. Are you going to work or continue to study after graduating school? and Q6. What field of nursing are you interested in?

Each question had closed-answers from which two or more items could be chosen, and an open-answer portion, allowing for free responses.

Subjects were ensured anonymity and provided informed consent to participate in this study. All data were analyzed by Student t-test, chi-square and Wilcoxon test using SPSS 12.0. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of Subjects

Japanese subjects consisted of five male and 27 female students with an average age of 21.78 (range: 21 - 30). Malagasy subjects consisted of 12 male and 15 female students (p < 0.05), with an average age of 24.11 (range: 18 - 39) (p < 0.001). No subject in Japan was married or had children, while of the 31 Malagasy students, six were married (p < 0.05) and seven had children (p < 0.01). Regarding religion, of the 24 Japanese students, 13 responded Buddhism, while 11 responded as having no religion. In comparison, 87.1% of Malagasy students responded as belonging to some sect of Christianity (i.e., Catholicism, Protestantism, or Adventist), while the remaining 12.9% did not say anything about religion

3.2. Why Do You Want to Become a Nurse? (Q1)

The subjects could choose two or more responses from 10 choices or respond freely. The choices were “Because I want to help sick people,” “Because I like nursing,” “Because I am interested in medical science,” “Because a nurse can earn much money,” “Because I have wanted to be a nurse since my youth,” “Because I want to contribute to society,” “Because I want to grow personally,” “Because it is a skilled profession,” “Because I want to help my family,” and “Because I want to obtain knowledge and skills related to medical science.” Three of these choices showed statistically significant response rates. More Japanese students than Malagasy students thought that nurses can earn much money and that nursing is a skilled profession (Figure 1).

3.3. What Kind of Nurse Do You Want to Be in the Future? (Q2)

The subjects could choose two or more responses from

Figure 1. Responses to Q1 “Why do you want to be a nurse?” More Japanese students chose “Because a nurse can earn much money” (p < 0.05) and “Because it is a skilled profession” (p < 0.05) than Malagasy students. More Malagasy students chose “Because I like nursing” (p < 0.05) than Japanese students.

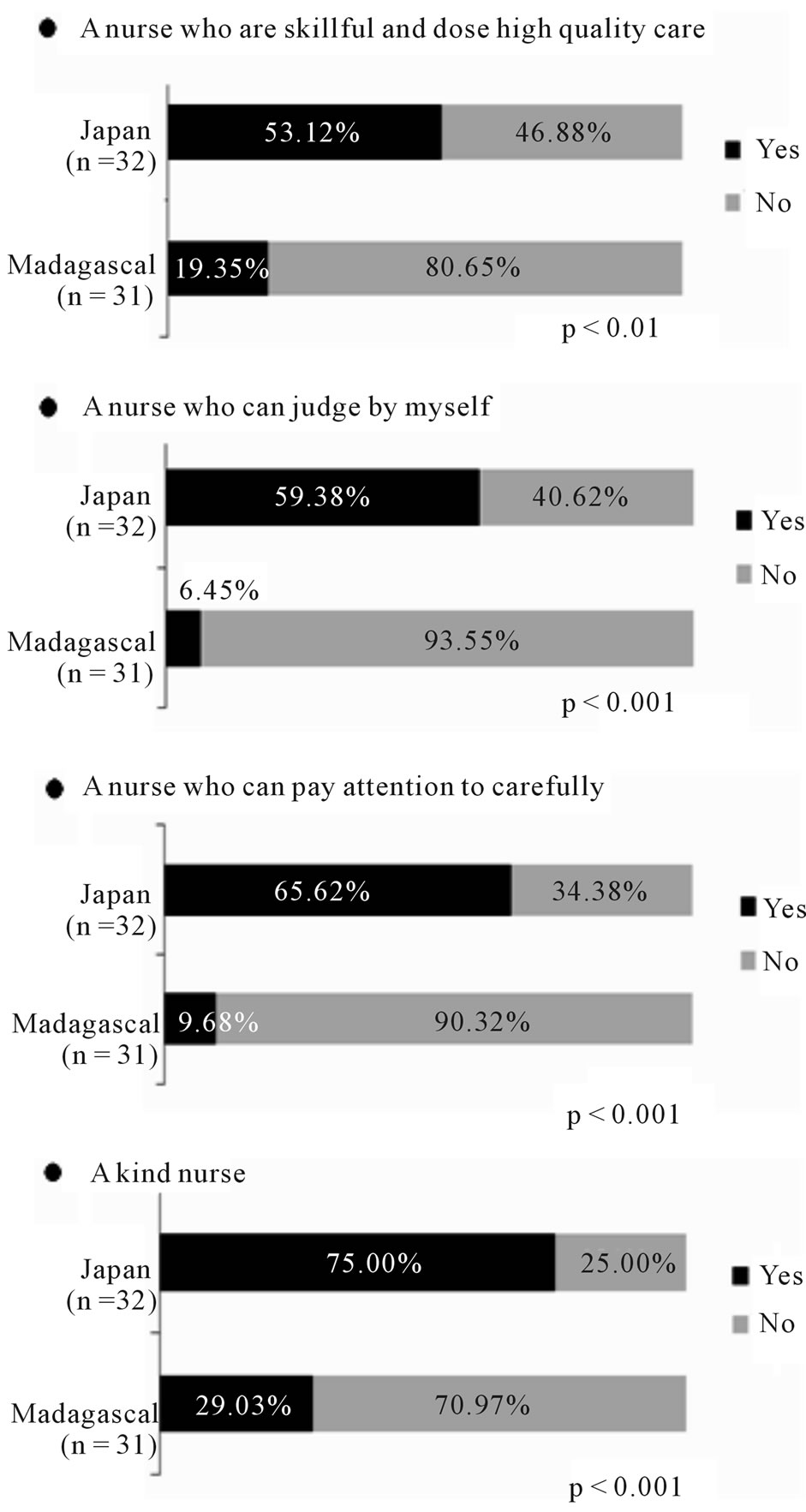

12 choices or respond freely. The choices were “An active nurse,” “A kind nurse,” “A talented nurse,” “A creative nurse,” “An intelligent nurse,” “A nurse who works in a medical scene,” “A nurse who works in an operating room,” “A nurse who is skillful and gives high quality care to the patient,” “A nurse who can make judgments by themselves,” “A nurse who works in surgery,” “A nurse who works in obstetrics and gynecology,” and “A nurse who can pay attention to detail.” Four of these choices showed statistically significant response rates. More Japanese students than Malagasy students wanted to be a skillful, kind, and self-reliant nurse (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Responses to Q2 “What kind of nurse do you want to be in the future?” More Japanese students chose “A nurse who is skillful and gives high quality care to the patient” (p < 0.01), “A nurse who can make judgments for themselves” (p < 0.001), “A nurse who can pay attention to detail” (p < 0.001), and “A kind nurse” (p < 0.001) than Malagasy students.

3.4. What Roles Do Nurses in Your Country Play? (Q3)

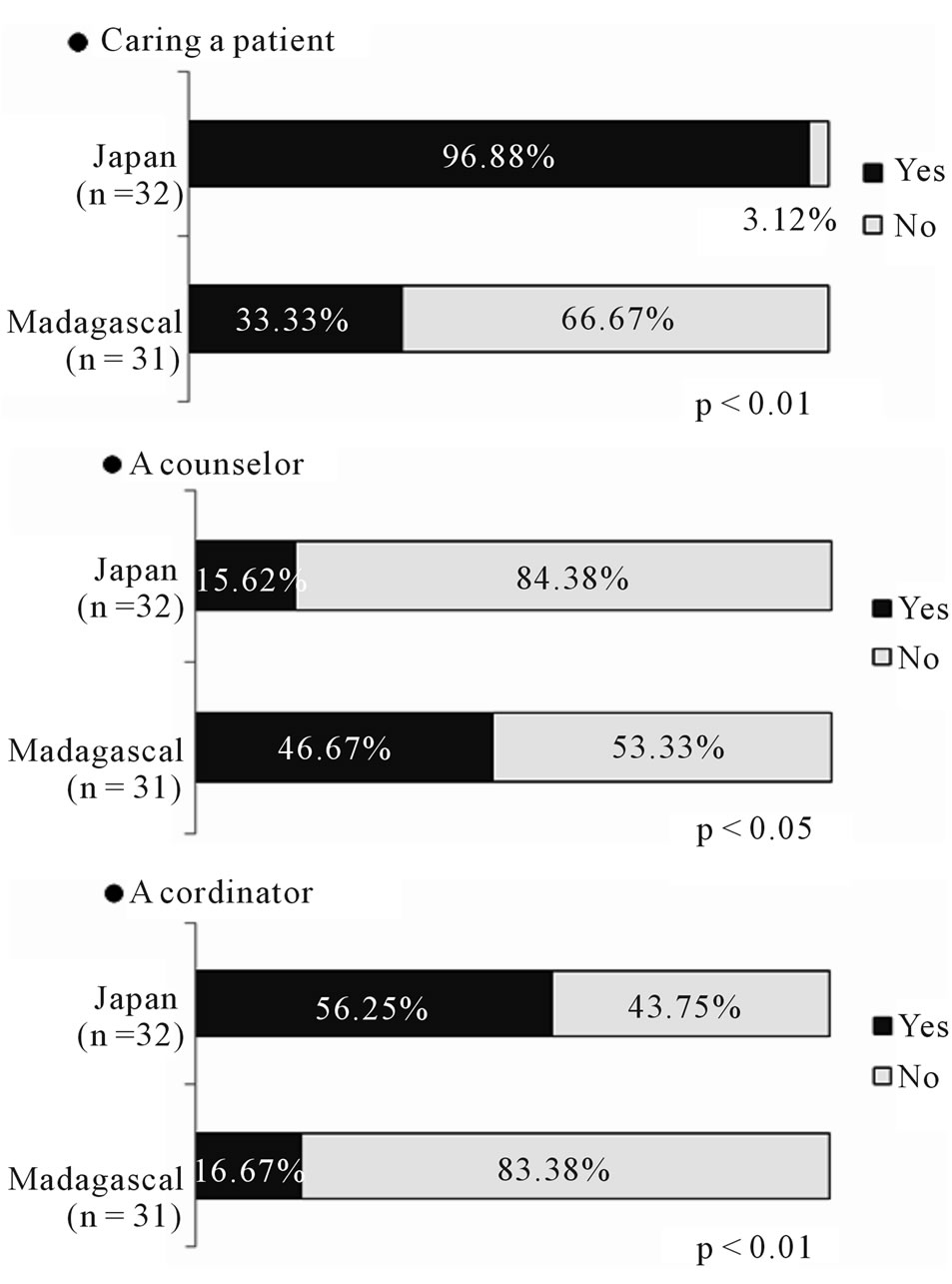

The subjects could choose two or more responses from 12 choices or respond freely. The choices were “a liaison between patients and doctors,” “An educator,” “Caring for a patient,” “Promoting people’s health,” “A counselor,” “Healing people,” “Assisting rehabilitation,” “Ensuring the right of health,” “A profession to be respected,” “A coordinator,” “A leader,” and “A person who makes decisions.” Three of these choices showed statistically significant response rates. More Japanese students than Malagasy students thought the nurse’s roles were to care for patients and to be a coordinator (Figure 3).

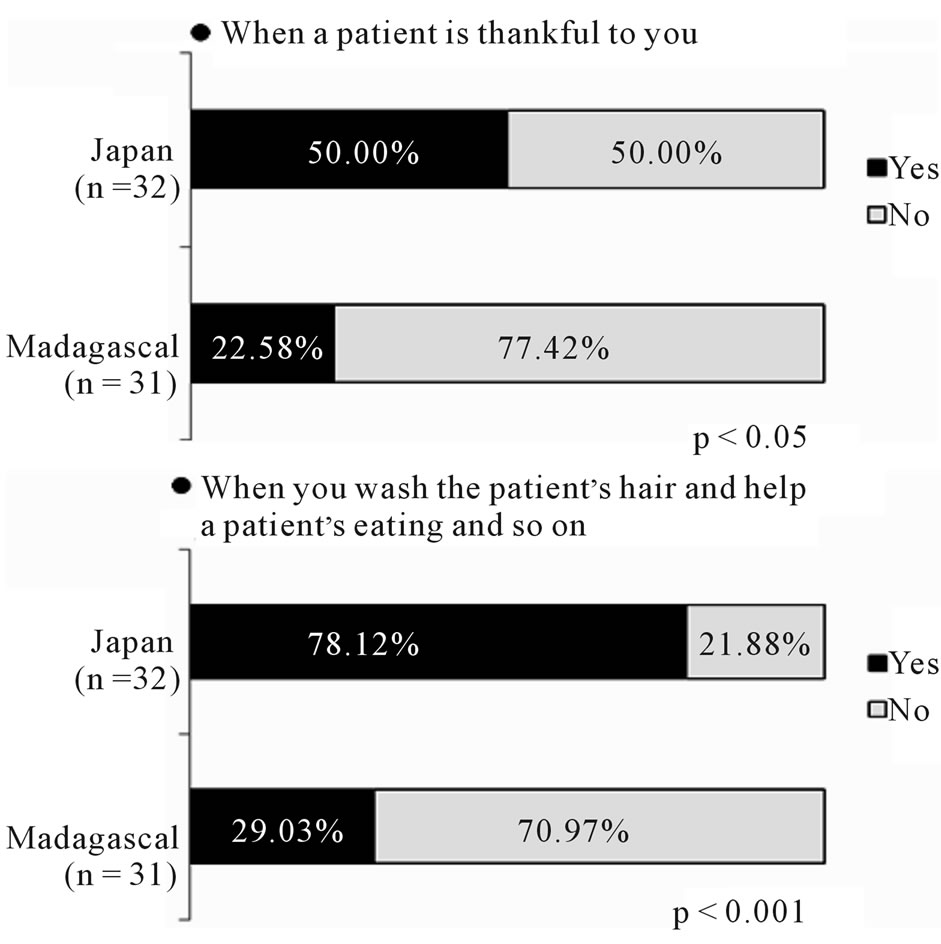

3.5. What Actions Make You Feel That You Are a Nurse When You Practice in the Hospital? (Q4)

The subjects could choose two or more responses from five choices or answer freely. The choices were “When a patient gets well,” “When I do medical treatment with a

Figure 3. Responses to Q3 “What roles do nurses in your country play?” More Japanese students chose “Caring for a patient” (p < 0.001) and “A coordinator” (p < 0.01) than Malagasy students. More Malagasy students chose “A counselor” (p < 0.05) than Japanese students.

nurse,” “When a patient is thankful to me,” “When I talk with a patient and can share the patient’s feelings,” and “When I wash the patients’ hair and body, help them eat, etc.” Two of these choices showed statistically significant response rates. More Japanese students than Malagasy students thought they were nurses when they were appreciated by patients and when they washed the patients’ hair and body, helped them eat, etc. (Figure 4).

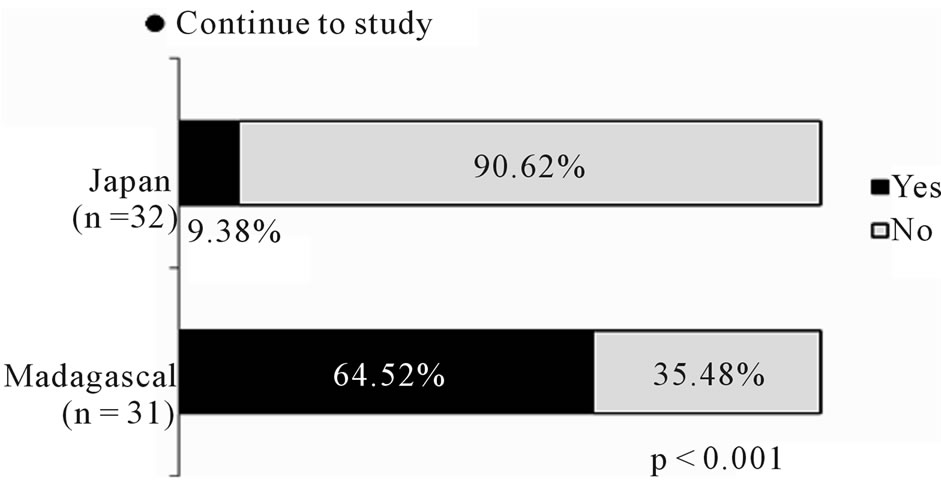

3.6. Are You Going to Work or Continue to Study after Graduating School? (Q5)

Subjects could choose either one or both of the following choices, “Work” and “Continue to study.” Twenty-nine of the Japanese students and 23 of the Malagasy students responded “work” (p < 0.05), while three Japanese students and 20 Malagasy students responded “Continue to study” (p < 0.001). No Japanese student chose both choices (Figure 5).

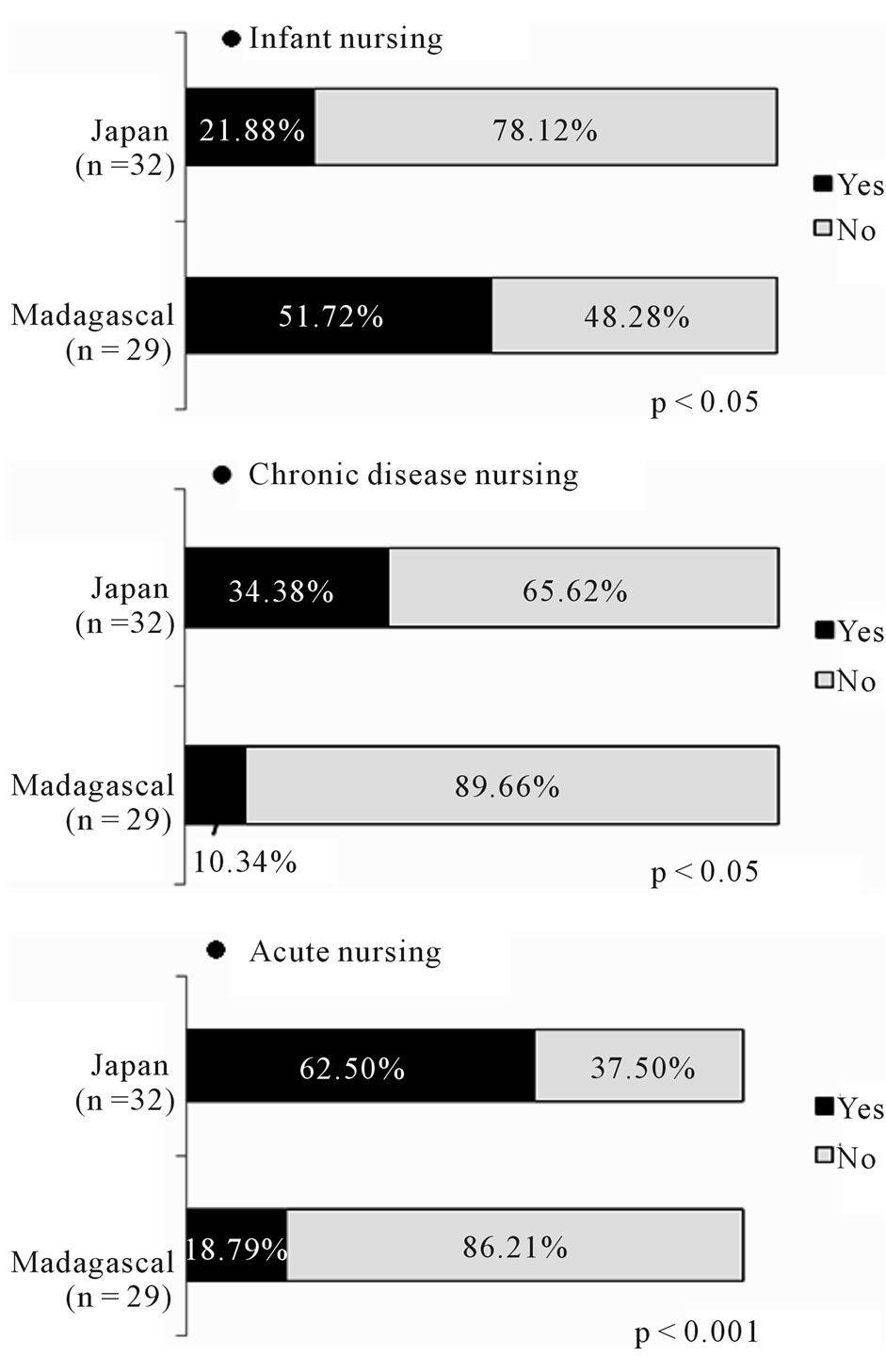

3.7. What Field of Nursing Are You Interested in? (Q6)

The subjects could choose two or more responses from seven choices or respond freely. The choices were “Infant nursing,” “Geriatric nursing,” “Maternity nursing,” “Nursing for chronic diseases,” “Nursing for acute diseases,” “Psychological nursing,” and “Community nursing.” Three of these choices showed statistically significant response rates. Malagasy students were interested in

Figure 4. Responses to Q4 “What actions make you feel that you are a nurse when you practice in a hospital?” More Japanese students chose “When a patient is thankful to me” (p < 0.05) and “When I wash the patients’ hair and body, help them eat, etc.” (p < 0.001) than Malagasy students.

infant nursing, while Japanese students were interested in nursing for chronic and acute diseases (Figure 6).

4. DISCUSSION

This study explored the differences between nursing

Figure 5. Responses to Q5 “Are you going to work or continue to study after graduating school?” More Malagasy students chose “Continue to study” (p < 0.001) than Japanese students.

Figure 6. Responses to Q6 “What field of nursing are you interested in?” More Japanese students chose “Nursing for chronic diseases” (p < 0.05) and “Nursing for acute diseases” (p < 0.001) than Malagasy students. More Malagasy students chose “Infant nursing” (p < 0.05) than Japanese students.

students in Madagascar and Japan through a questionnaire. The majority of Japanese nursing students who participated in this study were women. The number of Japanese male students was half that for Madagascar. Overall, the number of male students was less than that of females in both countries. This gender discrepancy may reflect the population of nursing students in these two countries. None of the Japanese students and some of the Malagasy students had children or were married. In Japan, few people marry as students. The mean age in Madagascar was higher than that in Japan, suggesting more Malagasy students begin to study nursing after marriage and having children. In Madagascar, there is an age limitation of 18 - 30 years for the public training institute, but not for private schools.

Buddhism is a major religion in Japan even though many students did not specify their religion in this survey. As many Japanese people do not actively pray or go to temples, Japan is considered to have a non-religious culture [7]. By contrast, religion has a strong place in Madagascar where Christianity is dominant [8]. Thus, it is not surprising that, unlike the Japanese students, the Malagasy students clearly responded to the question regarding their religion.

Malagasy students have a positive attitude toward nursing as opposed to Japanese students who think of nursing as security, social stability and economic development, as reflected in the higher number of Japanese students who think a nurse can earn much money and nursing is a skilled profession. In Madagascar, the social status of nurses is low and their job as medical staff does not provide enough money to feed their family [9]. The monthly income of an entry level Malagasy nurse in the public sector is about MGA 250,000 or about US$130 [10], compared to about $1987 per month in Japan [11]. This large gap in income may be reflected in the students’ attitudes toward nursing in their respective countries.

Most of the Japanese students want to become kind, independent nurses who are able to give high quality care and pay attention to detail. They also tend to have a desire to make the most of their specialty. These responses may reflect the opportunities of nursing specialties available in Japan.

Moreover, Malagasy students believe the nurse’s role is of a psychological nature. In Madagascar, the Institute of Inter-Regional Training Paramedics of Antananarivo specializes in mental health, which may influence how its students perceive nursing. The low income in nursing may also play a factor in the role of nursing in Madagascar. On the other hand, the Japanese students believe the nurse’s role is of a physical nature, focused on medical treatment: caring for the patient and coordination of care.

The actions that make many Japanese students feel they are nurses include being thanked by patients and doing actual physical care, such as washing hair or body or helping with eating. Such activities are not the responsibility of nurses in Madagascar. Rather, these are jobs for the patient’s family or caregiver. The responses by Japanese students suggest specific activities and feedback are required for Japanese nurses to achieve job satisfaction.

Many Malagasy students plan to continue their studies after graduating nursing school, compared to only a few Japanese students. In addition, some Malagasy students plan to both work and continue studying. Studying in school at the same time as working as a nurse could be more easily achieved in Madagascar than in Japan. Responses may also reflect the young Malagasy ambition to study. According to the summary report of the profile of nursing education in various francophone countries in 2008, specialized training is available in Madagascar for nursing graduates of state [12]. In addition, continued distance learning programs are available in sectors other than healthcare [13,14].

A popular specialty is infant nursing for Malagasy students, while acute and chronic diseases nursing are more popular among Japanese students. This result most likely reflects the actual medical situation in these countries, particularly in the areas where the students are located. In Madagascar, the infant and maternal mortality rates are high and many infants are in critical condition [15,16]. Thus, Malagasy students may feel the importance of nursing for infants. On the other hand, the quality of medicine in Japan is quite high and patients in critical condition can receive good healthcare. However, acute diseases often become chronic ones and thus proper control over the long term is needed. In addition, the number of deaths in Japan due to lifestyle-related diseases is increasing [17], and these diseases require long-term medical treatment. Therefore, the nursing field of acute and chronic diseases is becoming more familiar to Japanese students.

5. CONCLUSION

Malagasy students believe nursing involves psychological work which they have positive attitudes about. Japanese students, however, require concrete goals for nursing and tend to think that the role of a nurse is direct physical care through medical treatment. Japanese students emphasize outcome and the need for social and economic guarantees. These differences in the perception of nursing reflect the differences in the medical situations between Japan and Madagascar. However, this study was limited to less than a year and only pooled from a few nursing schools in Madagascar and Japan. Thus, our results may not accurately reflect the national situation of nursing students in each country. Increasing the number of students surveyed and the study period is needed to confirm these results.

REFERENCES

- WHO (2008-2010) Global Health Observatory Data Repository, Madagascar. http://apps.who.int/ghodata/?theme=country.html

- Madagascar-Health. Encyclopedia of the nations. http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Africa/Madagascar-HEALTH.html#b

- Randremanana, R.V. Sabatier P., Rakotomanana, F., Randriamanantena, A. and Vincent, R. (2009) Spatial clustering of pulmonary tuberculosis and impact of the care factors in Antananarivo City. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 14, 429-437. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02239.x

- WHO (2008-2010) Global Health Observatory Data Repository, Japan. http://apps.who.int/ghodata/?theme=country.html

- WHO (2007) Health situation and trend. http://www.wpro.who.int/countries/2007/jpn/health_situation.htm

- Shimano, T. (2009) Tuberculosis prevalence survey in Japan. Kekkaku, 84, 713-720.

- Religion in Japan from Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Region

- Madagascar Religion from Maps of World. http://www.mapsofworld.com/madagascar/society-and-culture/religion.html

- Rakotonirina, J. (2008) Staff’s health and quality of care in Madagascar. http://sites-test.uclouvain.be/stages-semspi/travaux/Rakoto1.html#1

- Mitsabo, M. (2011) Become a nurse in Madagascar. Nurse community. http://www.infirmiers.com/votre-carriere/exercice-international/devenir-infirmiere-a-madagascar.html

- Center for Migrant Advocacy-Philippines (2008) How much is the salary of nurses and caregivers in Japan? Pinoy Care in Japan. http://japan.pinoy-abroad.net/faq/how_much_salary.htm

- Seck, A. (2008) Profile of training in nursing in different francophone countries. International Secretariat of Nurses of the Francophone space. http://www.sidiief.org/Accueil/7_0_Publications/7_1_PublicationsSIDIIEF/~/media/09CA9E67470D4217B06D41D7E594F759.ashx

- Plager, K.A. and Razaonandrianina, J.O. (2009) Madagascar nursing needs assessment: education and development of the proferssion. International Nursing Review, 56, 58-64. doi:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00696.x

- Andrianarisoa, A.O. and Rampaniato, M. (1994) Primary health care centers in Madagascar. World Health Forum, 15, 248-250.

- Moursi, M.M., Treche, S., Martin-Prevel, Y., Maire, B. and Delpeuch, F. (2009) Association of a summary index of child feeding with diet quality and growth of 6-23 months children in urban Madagascar. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 63, 718-724. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2008.10

- Nagai, S., Yonemoto, N., Rabesandratana, N., Andrianarimanana, D., Nakayama, T. and Mori, R. (2011) Long-term effects of earlier initiated continuous Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) for low-birth-weight (LBW) infants in Madagascar. Acta Paediatrica, 100, e241-e247. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02372.x

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Specific health checkups and specific health guidance. Annual health, labor and welfare report 2008-2009. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw3/dl/2-007.pdf