Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.9, 969-977 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.29146 How Dialysis Patients Live: A Study on Their Depression and Associated Factors in Southern Italy Maria Sinatra1, Antonietta Curci1, Valeria de Palo1, Lucia Monacis2, Giancarlo Tanucci1 1Department of Psychology, University of Bari, Bari, Italy; 2Department of Human Sciences, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy. Email: m.sinatra@psico.uniba.it Received August 12th, 2011; revised September 20th, 2011; accepted October 29th, 2011. Depression is an independent risk factor of poor outcomes for Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) patients. Per- ceived social support and alexithymia are psychosocial variables identified by previous studies as predictive of depression in normal controls and CKD patients. Repetitively thinking and socially sharing emotional experi- ences have been investigated in association with depression in normal populations. Our cross-sectional study aimed to assess the effects of perceived social support, alexithymia, mental rumination, and social sharing on depression in CKD patients and controls. 103 CKD patients (age = 61.9 ± 7.2, 54 men) and 101 controls (age = 64.51 ± 6.56; 47 men) completed a questionnaire of 5 sections: Pluridimensional Inventory for Haemodialysis Patients (IPPE), Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Toronto Alexihymia Scale (TAS-20), Social Sharing and Mental Rumination. Multiple regression analy- sis models with dummy variables assessed the effects of IPPE, MSPSS, TAS-20, Social Sharing, and Mental Rumination on GDS across the subgroups of participants. SPSS software was used. Depression levels resulted higher for patients than controls, especially in patients dialyzed for less than 4 years. The effects of perceived social support and alexithymia differed with respect to the subsamples. Rumination was positively associated with depression in normal controls, but negatively related with depression in patients dialyzed for 4+ years. The study confirmed high levels of depression in CKD patients. Depression was influenced by perceived social sup- port, alexithymia, and the cognitive elaboration of emotional troubles associated with the disease. Rumination appeared as a dysfunctional consequence of emotions for normal controls, but had an adaptive function for pa- tients dialyzed for 4+ years . Keywords: Depression, Perceived Social Support, Alexithy mia, Mental R umination, Social Sharing, CKD Introduction Depression has been shown to be a common psychiatric dis- order in patients affected by chronic kidney disease (Hedayati et al., 2009). It has been found to be prevalent in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on long-term haemodialysis or following kidney transplantation, with an estimated prevalence rate between 15% and 40% (Ricardo et al., 2010). Previous studies have demonstrated that depression is an independent risk factor for poor outcomes in CKD patients (Hedayati et al., 2008; Hedayati et al., 2010). Social support has been defined as the availability of signifi- cant interpersonal relationships which make individuals feel cared for, esteemed, and valued (Sarason et al., 2009). The concept involves two broad aspects: 1) social support as actu- ally received (functional and structural support); 2) the indi- vidual’s subjective perception of availability of social support (perceived social support). It has been demonstrated that the availability of social support is an important protective factor against depression in chronic illnesses (Hoth et al., 1997). Fur- ther, the perception of social support has been found to be asso- ciated with reduction of depression, increased perception of quality of life, increased access to health care, compliance with prescribed therapies, and direct physiological effects on the immune system for patients with ESRD (Cohen et al., 2007). Individuals with available social support have more opportu- nities to talk about their state of health, diagnosed disease and symptoms, share their worries and concerns, and manage the emotional burden of their illness with significant others, such as spouses, family members, close friends. Among the behavioral consequences of the availability of social support there is a phenomenon called social sharing, which entails the description, in a socially shared language, of emotional events to an ad- dressee by the person who experienced them (Zech & Rimé, 2005). Social sharing has been demonstrated to be a highly pervasive phenomenon, since it occurs after an emotional ex- perience in 80% to 95% of cases in all countries and cultures (Rimé, 2009). In samples drawn from normal populations so- cial sharing has been found to be associated with increased health benefits as assessed by physician visits, reported symp- toms, immunological functions, and indices of subjective well-being (Frattaroli, 2006). Social sharing is generally associated with another process called mental rumination, i.e. the intra-individual persistence of thoughts, images, and physiological symptoms related to an emotional experience. Rumination has been originally regarded as a strategy for coping with emotional experiences. According to this view, rumination arises when individuals experience interruptions while pursuing their goals, and emotions originate as a consequence of these interruptions. The more relevant the interrupted goal, the higher the need for the individual to re- store it. Rumination is the strategy adopted by individuals to deal with the interruption of progress towards their goals, and it terminates when the objective is reached or is deemed imprac- ticable and then abandoned (Martin & Tesser, 1989). On the other hand, numerous studies have suggested a close relation-  M. SINATRA ET AL. 970 ship between rumination and depression since, through mental rumination, depressed individuals keep focusing on their symptoms and the possible consequences. This has in turn the effect of increasing the state of depression in a self-perpetuating cycle of self-focused thoughts (Roberts, Gilboa, & Gotlib, 1998). The constructs of social sharing and mental rumination have been broadly investigated in the field of psychology of emo- tions. Another important line of research focuses on the asso- ciation between rumination and a personality trait called alexithymia, which has been conceptualized as an individual deficit in identifying, communicating, and regulating emotions. Alexithymia is a multifaceted construct including three salient features: 1) difficulty identifying feelings and discriminating them from bodily sensations of emotional arousal; 2) difficulty expressing emotions and describing them to others; 3) limited capacity to engage in fantasy and other imaginative activities (Taylor, 1994). The construct of alexithymia has relevant im- plications for individuals’ health, since it has been found to be associated with a broad range of psychiatric symptoms, psy- chosomatic problems, and chronic illnesses (Taylor, 1994; Kauhanen et al., 1996). Alexithymia has also been demon- strated to be a stable risk factor for the development of depres- sive disorders in cross-sectional and cohort studies on general and clinical samples (Grabe, Spitzer, & Freyberger, 2004). Studies have examined the independent contribution of social support and alexithymia on depression (Kojima et al., 2007) and on long-term mortality (Kojima et al., 2010) of CKD pa- tients. However, to our knowledge, no studies have compared the conditional effects of social support, alexithymia, sharing and rumination processes upon depression of ESRD patients and controls. The present study has two main goals: 1) to con- firm the findings concerning the higher prevalence of depres- sion in ESRD patients; 2) to evaluate the relationship between depression, social support, alexithymia, mental rumination, and social sharing of emotionally relevant experiences. Indeed, we expected that ESRD patients would suffer from depressive disorders to a higher extent than controls, and that social sup- port and sharing would be valuable protective factors against patients’ depressive disorders, while alexithymia and mental rumination would have the opposite effect. Subjects and Methods Subjects The data for this cross-sectional study were collected by means of a computerized database containing demographical and clinical information regarding all consecutive ESRD pa- tients, older than 18 years, entering maintenance dialysis treat- ment programs at three dialysis units in Southern Italy from 1 January 1995. This group was made up of 103 subjects who have been undergoing dialysis treatment programs for at least 1 year. Table 1 contains their demographical characteristics. Matched for age, gender and race with the patients’ subsample, a group of 101 elderly participants were also involved in the study (age = 64.51 ± 6.56; 47 men). Data Collection On the basis of previous reports, the covariates identified a priori as possible risk factors for depression were age, gender and, for the clinical subsample, time elapsed since the begin- ning of haemodialysis programs. Indeed both the clinical his- tory and examination of the patients were taken into considera- tion in order to assess the comorbidities according to the ICED score (Miskulin et al., 2003). The ICED score aggregates the presence and severity of 19 medical conditions and 11 physical impairments within two scales: the Index of Disease Severity (IDS) and the Index of Physical Impairment (IPI). The final ICED score (ranged from 0 to 3 reflecting increasing severity) is determined by an algorithm combining the peak scores for the IDS and IPI. All the patients underwent a 4 h dialysis ses- sion thrice weekly, on high and low-flux membranes, on stan- dard bicarbonate dialysate, using 15-gauge fistula needles. The patients were anticoagulated by using systemic heparin. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of patients involved in the study. Design and Procedure The present study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration for studies on humans and it was approved by the local ethics committee. All participants were involved in the study on a voluntary basis. Before answering the question- naire they were required to give informed consent. The whole session lasted 30 minutes on average. Patients were recruited while waiting to undergo routine medical treat- ments in hospital; controls were recruited from among the re- searchers’ acquaintances. Participants were asked to fill in a questionnaire made up of different sections. The first section contained the IPPE (Pluridimensional In- ventory for Haemodialysis Patients) (Biasioli & Ballaben, Table 1. Patients demographical and cl inica l char acteri stics . N 103 Age (years) 61.9 ± 7.2 Gender (M/F) 59/44 Race 100% Caucasian Renal Disease s (% of the patients) Glomerular 20.9 Hypertensive 52.9 Vascular 10.0 Tubulo-Interstitial 16.2 Comorbidities (n/% of patients) Diabetes 24/22.9 Hypertension 44/41.9 Chronic Heart failure 29/27.6 Arrhythmia 7/6.7 Stroke 28/26.6 Peripheral Vasculopathy 20/19.3 Chronic lung di seases 8/7.6 Neoplasms 10/9.5 Biasioli, S., & Ballaben, P. Liver disea s es 6/5.7 ICED Score (%) 0 16.2 1 17.1 2 33.3 3 33.4  M. SINATRA ET AL. 971 2003), an instrument specifically intended to assess the quality of the psychological life of haemodialysis patients through 24 sentences to be rated on 4-point scales. The IPPE comprised 6 dimensions (family relationships, body, need to drink, daily life, medical support, perception of CKD state). This section was omitted for control participants. The second section contained the MSPSS (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support) (Zimet et al., 1988), a 12- item inventory of 7-point scales, assessing 3 dimensions of perceived social support concerning family, friends, and sig- nificant others. The third section contained the GDS (Geriatric Depression Scale) (Yesavage et al., 1983), an inventory consisting of 30 dichotomies (yes/no) designed to evaluate depressive symp- toms in elderly people. The fourth section contained the TAS-20 (Toronto Alexithy- mia Scale) (Parker, Taylor, & Bagby, 2003), a 20-item inven- tory of 5-point scales, assessing 3 dimensions of alexithymia, concerning difficulty in identifying feelings, difficulty in de- scribing feelings, and externally oriented thinking. Finally, the fifth section enclosed measures of intensity of emotion (11-point scale, ranging from 0 = no emotion to 10 = the highest degree of emotion in life), and the consequent social sharing and mental rumination processes (5-point scales rang- ing from 1 = never to 5 = very often, concerning need for shar- ing, actual social sharing, frequency of thinking, frequency of spontaneous images) (Rimé, Mesquita, Philippot, & Boca, 1991). For the patients’ groups, the measures in Section 5 re- lated to the experience of first hearing of the CKD diagnosis; for the control group, the questions related to the highest degree of emotional event experienced in recent years. Statistical Analyses Analyses were run on the aggregated indices obtained for each scale in the questionnaire. More specifically, for the IPPE, six indices were computed by averaging the items of the scales (Biasioli & Ballaben, 2003), i.e. Family relationships, Body, Need to drink, Daily Life, Medical Support, Perception of CKD state (Cronbach’s alphas = .80 on average). For the MSPSS, the three dimensions of Family, Friends, and Significant Others were obtained by averaging four items for each dimension (av- erage Cronbach’s alpha = .96) (Zimet et al., 1988). GDS items were dichotomies summed to obtain a general score for De- pression. This score ranges from 0 (=not depressed) to 30 (= max depression), with a cut-off of 11 corresponding to the presence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms, and a cut-off of 18 corresponding to the presence of severe depressive symptoms (Yesavage et al., 1983). For the TAS-20, items were selectively summed to obtain three aggregated scores corre- sponding to Difficulty in Identifying Feelings (DIF), Difficulty in Describing Feelings (DDF), and Externally-Oriented Think- ing (EOT) (average Cronbach’s alpha = .70) (Parker, Taylor, & Bagby, 2003). Finally, for the fifth section of the questionnaire, scores for need for sharing and actual social sharing were aver- aged into a composite index of Social Sharing; scores for fre- quency of thinking and frequency of spontaneous images were averaged into a composite index of Mental Rumination (aver- age Cronbach’s alpha = .87). Preliminarily, patients were classified in two groups: Those who have been undergoing haemodialysis treatment programs for less than 4 years (2.05 ± .87 years; 56.3%), and those who have been treated with haemodialysis programs for more than 4 years (10.00 ± 5.01 years; 43.7%). This choice was made for two reasons. The first was that after an average of four years undergoing haemodialysis treatment, CKD patients are eligible for kidney transplantation (Leichtman et al., 2008). It follows that 4 years represent an important cut-off point in the life of dialyzed patients. The second reason is statistical: in the subse- quent analyses the cut-off of 4 years was found to maximize the effect size for all comparisons. In a second step, GDS levels (absence of depressive symp- toms vs. mild depressive symptoms vs. severe depressive symptoms) were compared across the three groups of partici- pants (dialyzed patients for less than 4 years vs. dialyzed pa- tients for 4+ years vs. controls). Further, responses to Section 5 of the questionnaire were analyzed to verify whether patients’ experience of hearing of the CKD diagnosis was comparable with the occurrence of a high-level emotional experience for controls. In a third step, average IPPE scores were compared across the two groups of patients through a Multivariate model of Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). A second MANOVA was then run to compare the average MSPSS, GDS, TAS-20, Soc ial Sharing, and Mental Rumination scores across the two sub- groups of patients and the control group. Post-hoc analyses were carried by applying Tukey’s HSD test on the average scores for the three subgroups. Finally, multiple regression analysis models with dummy variables were employed to assess the effects of IPPE, MSPSS, TAS-20, Social Sharing, and Mental Rumination on GDS scores across the subgroups of participants. First, a multiple regression model was run on the total sample data, with the GDS scores as dependent measures. Two dummy variables— Condition (control = 0, patients = 1), and Gender (female = 0, male = 1)—and a set of continuous predictor variables (Age, the three MSPSS scores, the three TAS-20 scores, Social Shar- ing, Mental Rumination) were entered in the model, as well as their 2-way, 3-way, and 4-way interaction terms. However, only the test of the simple slopes (i.e., the 4 conditions in Table 2) was analyzed, and the conditional effects for all predictors in the model (dummy and continuous variables) were retained. The main advantage of the procedure consists in the opportu- nity to examine the conditional effects of each predictor in the model, i.e. the effect of a given variable when other interacting variables are included in the model. To make easier the inter- pretation of the effects, all continuous predictor variables were centred before running the analysis. The reference categories for the dummy variables in the model were control = 0 and female = 0. Second, a multiple regression model was run on the subsample of patients to assess the effects of the Duration of their haemodialysis program (dummy variable with 0 = less than 4 years vs. 1 = 4+ years), IPPE, MSPSS, TAS-20, Social Sharing, and Mental Rumination scores on their GDS scores. In this model, Gender and Age were not considered as covariates since introducing their interaction terms with the other predic- tors would have dramatically affected the degrees of freedom of the model. It follows that only the 2-way interactions of the dummy variable with the other continuous predictors were analyzed, and the conditional estimates of the simple slopes for the two subgroups of patients were reported in Table 3. All data were processed using SPSS software . Results As shown in Table 1, most patients were chara cterized by an ICED score higher than 2, reflecting the usual features found  M. SINATRA ET AL. 972 Table 2. Multiple regression an alysis with dummy and continuous predictor variables o n the GDS scores—total sample. Predictors R-squared = .81 F(69, 129) = 8. 12**** Beta (SE) Gender Female Male Condition 0 = control 1 = dialysis 9.71 (3.05)*** 1.86 (1.68) Condition Control Dialysis Gender 0 = female 1 = male 2.48 (2.13) -5.37 (2.39)* Female control Male control Female dialysis Male dialysis Age .57 (1.18) **** .02 (.24) .74 (.29) * .18 (.12) MSPSS – Family –.79 (.46) –1.02 (.42)** .48 (.70) .25 (.35) MSPSS – Friends .38 (.38) .49 (.29) –1.05 (.82) –.56 (.18)*** MSPSS – Others .57 (.37) .19 (.30) .06 (. 96) –.47 (.30) TAS-20 – DIF .22 (.19) .26 (.30) .10 (. 51) 1.02 (.19)**** TAS-20 – DDF .58 (.37) 1.08 (.39)** .98 (.85) –1.46 (.43)**** TAS-20 – EOT .19 (.28) –.29 (.49) –.42 (.45) 1.02 (.25)**** Social sharing .48 (.99) –1.03 (1.36) 2.23 (3.95) –1.76 (.93) Mental rumination 3.69 (1.15)*** 3.91 (1.58)* –1.55 (3.46) –.68 (1.25) Notes: All regressions have as reference categories controls = 0 and female = 0; Beta coefficients are shown with their SE in paren- thesis, and the significance level of the associated t-test with 1 df; The sign of the beta coefficient is positive for the cell corre- sponding to di alyzed and female participants, acco unting for a positi ve association between these two conditions, an d negative for the cell of dialyzed and male patients accounting for a negativ e asso ciat ion be tween these t wo condit ions; *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .005, ****p < .001. worldwide in the dialysis units during everyday clinical practice. Thus our cohort of patients is to be considered as representative of the typical uremic population, making the results found in this paper easily applicable to all real situations. The preliminary analysis of the GDS levels across the three subgroups of participants (dialyzed patients for less than 4 years vs. dialyzed patients for 4+ years vs. controls) yielded significant results (chi-square (4, N = 204) = 21.21, p < .001). Figure 1 showed that the absence of depressive symptoms was more frequent for controls than for patients, while dialyzed patients for less than 4 years appeared generally more de- pressed than patients undergoing haemodialysis programs for 4+ years (respectively 79.3% and 64.4% mild to severe depres- sive symptoms). With respect to the data from Section 5 of the questionnaire, for the patients, the experience of first hearing of the CKD di- agnosis dated back 9.73 ± 7.87 years, while for the control group, the recalled emotional event was significantly more recent, dating back 2.52 ± 2.32 years on average (t(167) = 7.62, p < .001). Among the control participants, 30.7% recalled a personal or family health problem due to illness or accident, 23.8% reported the death of a close relative or friend, 12.9% relational troubles (i.e. relationship breakdown, divorce, etc.), 11.9% problems at the workplace, 6.9% family problems, 4.0% victimization experiences (i.e. being robbed, assaulted, etc.), while 9.9% of controls failed to recall a specific emotional experience. Only 8 of the CKD patients were not able to recall the moment they first knew of their diagnosis. No significant difference was found between the emotional impact of the first hearing of the CKD diagnosis for the pa- tients’ subgroup and the emotional experience of the controls (respectively, 9.05 ± 1.85, and 8.77 ± 2.10, t(195) = 1.01, n.s.). Similarly, no significant differences were found between the patients and the control subgroups in the measures of Social Sharing (respectively, 3.38 ± 1.10, and 3.48 ± 1.08, t(198) = .70, n.s.), and Mental Rumination (respectively, 4.42 ± .63, and 4.20 ± .94, t(197) = 1.92, n.s.). In a subsequent step, average measures of IPPE were com- pared across the two subgroups of patients (less than 4 years vs. 4+ years dialyzed). The multivariate Fisher’s F for the MANOVA was found to be significant (F(6, 96) = 7.28, p < .001). As shown in Figure 2, this effect was due to the sig- nificant differences in three of the IPPE dimensions, corre- sponding to Body (F(1, 101 = 6.30, p < .05), Medical Treat- ments (F(1, 101) = 7.72, p < .01), and Perception of the CKD State (F(1, 101) = 22.58, p < .001) in those patients undergoing haemodialysis treatment programs for 4+ years reporting higher scores on these subdimensions than patients undergoing haemodialysis for less than 4 years. The overall result of the MANOVA on the MSPSS, GDS, TAS-20, Social Sharing, and  M. SINATRA ET AL. 973 Table 3. Multiple regression analysis with dummy and continuous predictor vari- ables on the GDS scores—patients’ subsample. Predictors R-squared = .89 F(29, 71) = 19.35**** Beta (SE) Dialysis duration 0 = Up to 4 years 1 = 4+ yea r s 1.92 (1.49) Less than 4 years 4+ years Ippe—familia r relationships –.61 (1.43) –4.84 (1.80) ** Ippe—body –1.09 (.63) 1.05 (.95) Ippe—need to drink .98 (.77) –.42 (1.3 1) Ippe—daily life –1.47 (.99) –2.33 (1.73) Ippe—medical support 3.71 (1.1 8)*** 1.90 (1.57) Ippe—Perce pt ion of C KD state –.15 (.67) 1.01 (1.31) MSPSS—Family .66 (.27)* –1.05 (.45)* MSPSS—Frie nds –.22 (.15) –.39 (.16)* MSPSS—Others –.45 (.23) .41 (.39) TAS-20—DIF .68 (.13)**** .34 (1.44) TAS-20—DDF .70 (.24) *** –.17 (.47) TAS-20—EOT –.36 (.19) .75 (.29)* Social sharing –1.38 (.85) 1.49 (.75) Mental rumination .52 (.99) –2.97 (1.25)* Notes: All regressions have as a reference category less than 4 years haemodi- alysis = 0; Beta coefficients are shown with their SE in parenthesis, and the sig- nificance level of the associated t-test with 1 df; *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .005, ****p < .001. 0 10 20 30 40 50 controlsdialyzed up to 4 yearsdialyzed 4+ years Pct . 60 absent mild severe Figur e 1. Distribution of GDS levels ac ross the three subgroups of participants. Mental Rumination scores by condition (patients dialyzed for less than 4 years vs. patients dialyzed for 4+ years vs. controls) were also found to be significant (F(18, 376) = 7,26, p < .001). As shown in Figure 2, this was due to the significant differ- ences across groups in the GDS (F(2, 196) = 4.33, p < .05) and TAS-20-DIF scores (F(2, 196) = 15.83, p < .001), with the highest scores reported by patients who had been undergoing haemodialysis programs for less than 4 years, and the lowest reported by controls (Tukey’s HSD ps < .05). The results of the first multiple regression analysis run on the total sample GDS scores are reported in Table 2. The model generally has a good fit. Women dialyzed appeared as the most depressed subgroup, and age affected depression for both dia- lyzed and control females. Social support had a negative impact on depression for male participants: More specifically, social support from Family negatively affected GDS scores for male controls, while social support from Friends negatively affected GDS scores for male patients. All three dimensions of TAS-20 impacted upon GDS scores for male patients, with DFI and EOT being positively associated, and DDF negatively associ- ated. By contrast, DDF was associated with a positive beta coefficient for male controls. Finally, Social Sharing was never associated with GDS scores, while Mental Rumination was found to have a significant positive impact upon GDS for con- trol participants. The results of the multiple regression analysis run on pa- tients’ GDS scores are reported in Table 3. This model has a good general fit. For patients undergoing haemodialysis pro- grams for less than 4 years, significant predictors of GDS ap- peared to be the IPPE-Medical Support, DIF, and DDF dimen- sions. For patients undergoing haemodialysis treatment pro- grams for 4+ years, significant predictors proved to be IPPE- Familiar Relationship, MSPSS-Family, MSPSS-Friends, EOT, and Mental Rumination. All these predictors exhibited negative associations with GDS scores except the EOT dimension, whose beta coefficient was found to be positive. Discussion Results of the present study confirmed the higher prevalence of depression among CKD patients as compared with normal controls. In addition, patients undergoing haemodialysis treat- ments for less than 4 years appeared comparatively more de- pressed than patients dialyzed for 4+ years. This finding is con- sistent with the assumptions of the Kübler-Ross (2009) five- stage model of attitudes toward death. According to this model, terminally ill patients undergo five stages of elaboration of their grief: Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance. Depression precedes the final stage of Acceptance. In the stage of Depression, terminally ill patients are aware of the losses they have suffered because of their state of health (reactive depression), and became progressively more aware of the fact that these losses are going to increase (preparatory depression). Subjective pain and practical implications of the disease and necessary medical treatments are amplified. Patients experience a sense of defeat. In the subsequent stage, called Acceptance, patients have had the chance to elaborate their experience, so that they become aware of its inevitable ending. Feelings of anger and depression may still be experienced, nonetheless they have moderate intensity. At this stage patients may experience a sense of profound intimacy with their close relatives. It should be noted that Acceptance does not necessarily overlap with the very final phase of the illness, when patients may still experi- ence denial, anger or depression. Besides the drawbacks mainly due to the limited empirical support for the model (Maciejewski, Zhang, Block, & Prigerson, 2007), the Kübler-Ross conceptu- alization represents a useful outline of the psychological proc- esses involved in the individual’s coping with a terminal dis- ease. As such, it could be applied to ERSD patients. In the pre- sent study we adopted a cut-off of 4 years to divide patients into two groups. We reasoned that after 4 years of haemodialysis treatments, patients are sufficiently aware of the serious impli- cations of their chronic diseas. After 4 years on average e  M. SINATRA ET AL. 974 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 Ippe familiar relationships Ippe body*Ippe need to drink I ppe da i l y l ifeIppe medical support** Ippe perception of CKD*** MSPSS FamilyMSPSS F riends M SPSS Others GDS *TAS-20 DIF** *TAS-20 DDFTAS-20 EO TSocia l sh arin gMental rumination Means M control M less than 4 years M 4+ years Figure 2. Ms and SDs IPPE, MSPSS, GDS, TAS-20, social sharing, and rumination . Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, **p < .001. from the beginning of their programs, patients generally have a chance of getting kidney transplantation (Leichtman et al., 2008). Whether or not they accept a transplant, in 4 years pa- tients have had the opportunity to elaborate their experience and accept the disease and its consequences. It follows that the cut-off of 4 years roughly parallels the distinction of the 5-stage model between the Depression and Acceptance phases. This intuition was confirmed by the statistical analyses run in the present study that showed that the cut-off of 4 years maxi- mized the effects for all comparisons. Dialyzed women appeared significantly more depressed than dialyzed men. Age also played a significant effect for women in both the dialyzed and control groups, since their depression increased with age. These findings are consistent with the lit- erature on gender differences in depression. It is well estab- lished that women are about twice as likely as men to develop depression across different cultures, and ethnicities (Nolen- Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999; Weissman et al., 1996). Even in presence of the same stressors, women are more likely to react with depressive disorders than men. Many ex- planations have been proposed for this fact, such as interper- sonal stress (Conger et al. 1993), self esteem (Cambron, Acitelli, & Pettit, 2009), cognitive and affective processes (Mezulis & Fanasaki, 2009; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993), biological and hormonal factors (Grigoriadis & Robinson, 2007), coping style (Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999; Broderick & Korteland, 2002), social and cultural constraints (Leach et al., 2008), although evidence is rather inconclusive on this regard. Additionally, in previous studies the effect of gender was also found to be more pronounced as age increases (Umberson, Wortman, & Kessler, 1992). Perceived family support had a significant effect upon de- pression of male controls, while friends’ support and alexithy- mia had a significant impact on depression in dialyzed men. These findings are of interest for the understanding of the pro- tective factors against depression and the treatment of depres- sive disorders. Elderly men suffer more from social isolation than women (Kendler, Myers, & Prescott, 2005). Further, alexithymia and related emotional difficulties have typically been found to be associated with male gender (Parker, Taylor, & Bagby, 2003; Lane, Sechrest, & Riedel, 1998). The percep- tion of low availability of social support and alexithymia make men susceptible to developing depression. By contrast, women generally have larger networks of significant others, and are affected by alexithymia to a lesser extent than men. This im- plies that treatment for depression focusing on reducing the sense of isolation and difficulty in expressing emotions would be more successful for men than for women. Finally, no sig- nificant effects were found for social sharing, while mental rumination increased depression in both male and female con- trols. This probably happens because individuals have failed to conclude the psychological elaboration of their emotional ex- periences. Repetitive thinking leads to the maintenance of a disturbing cycle of perseverating thoughts which in turn increase the nega- tive emotional state following the original experiences and the concurrent depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Nolen-Hoek- sema & Morrow, 1993). With respect to ESRD patients, al- though their level of depression was generally higher than for controls, ruminating about the first hearing of CKD diagnosis was not found to have effects on increasing their level of de- pression. Focusing on CKD patients, no significant differences were found in their level of perceived social support, social sharing, and mental rumination. Patients who had been undergoing haemodialysis treatment programs for 4+ years appeared less satisfied with their physical condition, required more medical treatments, were more concerned by their CKD state, and ex- perienced more difficulties in identifying feelings than patients who had been undergoing such treatments for less than 4 years. With respect to the effects of the perceived quality of life and social support variables in the regression model, it should be  M. SINATRA ET AL. 975 noted that the signs of the coefficients are different for the two subgroups of patients: while perceived quality of life and per- ceived social support diminished the level of depression in patients dialyzed for 4+ years, these variables had either the opposite or no effects at all on depression in patients dialyzed for less than 4 years. This accounts for the fact that, although the patients’ perception of quality of life and the level of per- ceived support do not change during the course of the treatment program, these perceptions have the beneficial effect of reduc- ing patients’ depression only in the very last stages of the dis- ease. This is consistent with what was reported above concern- ing the stages of psychological elaboration of the disease by terminally ill CKD patients (Kübler-Ross, 2009). In the stage called Acceptance, patients might rely upon their individual and social resources to cope with their disease. Depression could be alleviated by the perception of significant ot hers being ava ilable to provide support, and by an ultimate adjustment with the ESRD difficulties. Alexithymia also had a significant effect on CKD patients’ depression, but this effect involved different dimensions with respect to the duration of patients’ haemodialysis program: while DIF and DDF increased depression in patients dialyzed for less than 4 years, the EOT dimension intensified depression in patients who had been undergoing haemodialysis program for 4+ years. The first two dimensions of TAS-20 have fre- quently been found associated with depression in a number of studies run on both normal and psychiatric samples (Marchesi, Brusamonti, & Maggini, 2000; Hendryx, Haviland, & Shaw, 1991). With respect to the EOT dimension, it could be possible that 4+ years dialyzed patients prefer to employ introspective strategies of thinking to regulate their depressive symptoms. Focusing on their internal psychological states might be useful for long-term dialyzed patients to reduce the psychological burden of living with their disease. On the other hand, it has been variously shown that the subscale EOT has a lower inter- nal consistency and more problematic psychometric properties than the other two TAS-20 dimensions (Gignac, Palmer, & Stough, 2007; Kooiman, Spinhoven, & Trijsburg, 2002). Also in this study, the EOT Cronbach’s alpha (.52) is lower than the alphas of the DIF and DDF dimensions (respectively, .90 and .70). Therefore, these measurement issues may have inter- fered with our results (Gignac, Palmer, & Stough, 2007). Finally, social sharing processes did not exhibit significant associations with CKD patients’ depression, but mental rumi- nation had the effect of reducing depression in patients dialyzed for 4+ years. Unlike controls, CKD patients dialyzed for 4+ years employed rumination strategies in an adaptive way. Far from being the effect of a dysfunctional persistence of un- wanted thoughts, rumination appeared to be a useful way of reducing the symptoms of depressive disorder and appease the individual in the terminal phases of CKD. One possible theo- retical explanation for these findings is that mental rumination serves as a strategy for coping with interruptions in pursuing significant goals. Through rumination, individuals attempt to reduce disruption, and reinstate the unaccomplished goals (Martin & Tesser, 1989). The unpredictability of CKD and the imminence of death certainly represent for ESRD patients the ultimate interruption of their life goals (Schipper & Abma, 2011). Ruminating may help patients to restore this interruption and create a sense of prolongation of their life beyond illness and death. A definitive empirical evaluation of this interpreta- tion would be possible by analyzing the contents of CKD pa- tients’ ruminative thoughts, and comparing them with the self- evaluated coping strategies adopted by patients to deal with health issues. This would be an interesting avenue for future research on the factors associated with depression in CKD pa- tients in order to prevent poor outcomes in their treatment. Some comment is required on the absence of significant rela- tionships between social sharing processes and depression in both CKD patients and controls. These findings contradict the expectations of the present study, and leave unsolved the prob- lem of defining the behavioural processes through which the perception of social support reduces depressive symptoms. It might be that individuals do not need to share the content of their emotional experiences to reduce depression, and that sim- ply figuring out that significant others are available to provide support when needed is sufficient to alleviate the state of de- pression. Alternatively, it is possible that social sharing is not the only way people exchange and receive support, and that the mere presence of significant others, their availability to provide material goods or practical assistance are important instances of social support. Again, future research work could help to clarify the issue concerning social and psychological factors contrib- uting to the alleviation of depression in CKD patients. The present study has some limitations. First, the relation- ships between patients’ depression, perceived social support, alexithymia, social sharing, and mental rumination of emotions need to be investigated through a cohort design in order to evaluate the temporal evolution of these relationships and the different impact of the psychosocial factors with respect to the progression of CKD. Employing a cohort design would also help to clarify the issue of the causal relationship between de- pression and adverse outcomes in CKD patients. Second, as- sessing CKD patients’ depression has often been recommended as a clinical means of ensuring accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up (Watnick, 2007). However, no spe- cific instruments are available to evaluate depression in CKD patients. The most frequently used inventories for this purpose are the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Craven, Rodin, & Littlefield, 1988) the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depres- sion Scale (CESD) (Andresen et al., 1994), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Watnick, Wang, Demadura, & Ganzini, 2005). These instruments are brief self-report scales for the screening of depression that have also been validated on samples of CKD patients. The sample for the present study consisted of individuals—dialyzed and controls—aged over 60. As a consequence, we employed the GDS as a specific instru- ment to assess depression in elderly individuals (Yesavage et al., 1983). Using GDS is not a common practice in research on CKD patients, thus the psychometric properties of the scale applied to CKD populations require careful consideration. Third, the sample of the present study needs to be enlarged in order to allow for an accurate analysis of the interactions be- tween the variables associated with depression and the covari- ates of the design (gender and age in the present study). Fourth, the sample for the present study consisted of elderly people, therefore results cannot be generalized to the entire population of patients undergoing haemodialysis programs. Fifth, in the present study the indices of quality of life for haemodialysis patients were included in the set of potential predictors of de- pression in ESRD patients. However, the perception of quality of life could also be considered a mediator variable in the rela- tionship between social support, alexithymia, social sharing, mental rumination, and patients’ depression. To test this hy- pothesis, mediation analysis or structural models of direct and indirect relationships should be employed and this in turn re- quires a considerable enlargement of the sample size. Finally, a deeper analysis of the content and characteristics of mental  M. SINATRA ET AL. 976 rumination is required. The pattern of results concerning the effects of rumination on depression found in the present study could be due to the fact that, when ruminating about past emo- tional events, individuals focus on different aspects of their experience and adopt different styles of thinking, which can in turn impact upon their level of depression (Watkins & Teasdale, 2001). To sum up, the present study offers interesting indications for the understanding of the relationship between psychosocial factors and depression in patients with CKD. As long as the state of disease progresses and patients’ need for medical treatments increases, psychological adjustment evolves towards an acceptance of the disease and a significant reduction in the psychological symptoms of distress. This process is influenced by the way people perceive others supporting them, individual personality traits, and the cognitive elaboration of emotional troubles associated with the disease. A purposeful analysis of the way these psychosocial factors impact during the progress- sion of CKD could bring important benefits for the therapy of ESRD patients. References Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., Patrick, D. L., & Radloff, L. S. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10, 77-84. Biasioli, S., & Ballaben, P. (2003). IPPE, inventario pluridimensionale per il paziente in Emodialisi. In Ospedale e Territorio. Roma: CIC Edizioni Internazionali. Broderick, P. C., & Korteland, C. (2002). Coping style and depression in early adolescence: Relationships to gender, gender role, and im- plicit beliefs. Sex Roles, 46, 201-213. doi:10.1023/A:1019946714220 Cambron, M. J., Acitelli, L. K., & Pettit, J. W. (2009). Explaining gen- der differences in depression: An interpersonal contingent self-es- teem perspective. Sex Roles, 61, 651-661. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9616-6 Cohen, S. D., Sharma, T., Acquaviva, K., Peterson, R. et al. (2007). Social support and chronic kidney disease: An update. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, 14, 335-344. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2007.04.007 Conger, R. D., Lorenz, F. O., Elder, G. H. Jr. et al. (1993). Husband and wife differences in resp on se to undesirable life events. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34, 71-88. doi:10.2307/2137305 Craven, J. L., Rodin, G. M., & Littlefield, C. (1988). The Beck Depres- sion Inventory as a screening device for major depression in renal di- alysis patients. International Journal of Psychiatry, 18, 365-374. doi:10.2190/M1TX-V1EJ-E43L-RKLF Frattaroli, J. (2006). Experimental disclosure and its moderators: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 1 3 2, 823-865. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823 Gignac, G. E., Palmer, B. R., & Stough, C. (2007). A confirmatory factor analytic investigation of the tas-20: Corroboration of a five-factor model and suggestions for improvement. Journal of Per- sonality Assessment, 89, 247-257. doi:10.1080/00223890701629730 Grabe, H. J., Spitzer, C., & Freyberger, H. J. (2004). Alexithymia and personality in relation to dimensions of psychopathology. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1299-1301. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1299 Grigoriadis, S., & Robinson, G. E. (2007). Gender issues in depression. Annals of Clinical Psychia tr y , 19, 247-255. doi:10.1080/10401230701653294 Hedayati, S. S., Bosworth, H., Briley, L. et al. (2008). Death or hospi- talization of patients on chronic haemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney International, 74, 930-936. doi:10.1038/ki.2008.311 Hedayati, S. S., Minhajuddin, A. T., Toto, R. D. et al. (2009). Preva- lence of major depressive disorder in CKD. American Journal of Kidney Disease, 54, 424-432. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.017 Hedayati, S. S., Minhajuddin, A. T., Afshar, M., Toto, R. D. et al. (2010). Association between major depressive episodes in patients with chronic kidney disease and initiation of dialysis, hospitalization, or death. JAMA, 303, 1946-1953. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.619 Hendryx, M. S., Haviland, M. G., & Shaw, D. G. (1991). Dimensions of alexithymia and their relationships to anxiety and depression. Journal of Personality Assessment, 56, 227-237. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5602_4 Hoth, K. F., Christensen, A. J., Ehlers, S. L., Raichle, K. A., & Laweton, W. J. (2007). A longitudinal examination of social support, agree- ableness and depressive symptoms in chronic kidney disease. Jour- nal of Behavioral Medicin e, 30, 69-76. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9083-2 Kauhanen, J., Kaplan, G. A., Cohen, R. D., Julkunen, J., & Salonen, J. T. (1996). Alexithymia and risk of death in middle-aged men. Jour- nal of Psychosomatic Re s ea rc h , 41, 541-549. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00226-7 Kendler, K. S., Myers, J., & Prescott, C. A. (2005). Sex differences in the relationship between soci a l s u p p ort and risk for major depression: A longitudinal study of opposite-sex twin pairs. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 250- 2 56. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.250 Kojima, M., Hayano, J. et al. (2010). Depression, alexithymia and long-term mortality in chronic haemodialysis patients. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 79, 303-11. doi:10.1159/000319311 Kojima, M., Hayano, J., Tokudome, S. et al. (2007). Independent asso- ciations of alexithymia and social support with depression in haemo- dialysis patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63, 349-356. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.002 Kooiman, C. G., Spinhoven. P., & Trijsburg, R. W. (2002). The as- sessment of alexithymia—A critical review of the literature and a psychometric study of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 1083-1090. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00348-3 Kübler-Ross, E. (2009). On Death and Dying, 40th anniversary edition. Abingdon: Routledge. Lane, R. D., Sechrest, L., & Riedel, R. (1998). Sociodemographic cor- relates of alexithymia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 39, 377-385. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90051-7 Leach, L. S., Christensen, H., Mackinnon, A. J., Windsor, T. D., & Butterworth, P. (2008). Gender differences in depression and anxiety across the adult lifespan: The role of psychosocial mediators. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43, 983-998. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0388-z Leichtman A. B., Cohen, D., Keith, D., O’Connor et al. (2008). Kidney and pancreas transplantation in the United States, 1997-2006: The HRSA breakthrough collaborative and the 58 DSA challenge. American Journal of Transplantation, 8, 946-957. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02173.x Maciejewski, P. K., Zhang, B., Block, S. D., & Prigerson, H. G. (2007). An empirical examination of the stage theory of death. JAMA, 297, 716-723. doi:10.1001/jama.297.7.716 Marchesi, C., Brusamonti, E., & Maggini, C. (2000). Are alexithymia, depression, and anxiety distinct constructs in affective disorders? Journal of Psychosomatic Re sea rch , 49, 43-49. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00084-2 Martin, L. L., & Tesser, A. (1989). Toward a motivational and struc- tural theory of ruminative thought. In J. S. Uleman, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thoughts (pp. 306-325). New York: Guilford. Mezulis, A. H., & Fanasaki, K. (2009). Modeling the gender difference in depression: A commentary on Cambron, Acitelli, and Pettit. Sex Roles, 61, 672-678. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9663-z Miskulin, D. C., Meyer, K. B. et al. (2003). Choices for Healthy Out- comes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) study. Comorbidity and its change predict survival in incident dialysis pa- tients. American J ou r na l of K idney Disease, 41, 149-161. doi:10.1053/ajkd.2003.50034 Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psy- chology, 100, 569-582. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569 Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1993). Effects of rumination and  M. SINATRA ET AL. 977 distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cognition & Emotion, 7, 561-570. doi:10.1080/02699939308409206 Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Larson, J., & Grayson, C. (1999). Explaining the gender difference in depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychiatry, 77, 1061-1072. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1061 Parker, J. D., Taylor, G. J., & Bagby, R. M. (2003). The 20-Item To- ronto Alexithymia Scale III. Reliability and factorial validity in a community population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 269-275. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00578-0 Ricardo, A. C., Fischer, M. J., Peck, A. et al. (2010). Depressive symp- toms and chronic kidney disease: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005-2006. Interna- tional Urology and Nephrology, 42, 1063-1068. doi:10.1007/s11255-010-9833-5 Rimé, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empiri cal review. Emotion Review, 1, 60-85. doi:10.1177/1754073908097189 Rimé, B., Mesquita, B., Philippot, P., & Boca, S. (1991). Beyond the emotional event: Six studies on the social sharing of emotion. Cogni- tion & Emotion, 5, 435-465. doi:10.1080/02699939108411052 Roberts, J. E., Gilboa, E., & Gotlib, I. H. (1998). Ruminative response style and vulnerability to episodes of dysphoria. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 401-423. doi:10.1023/A:1018713313894 Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2009). Social support: Mapping the construct. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26, 113- 120. doi:10.1177/0265407509105526 Schipper, K., & Abma, T. A. (2011). Coping, family and mastery: Top priorities for social science research by patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrololgy Dialysis Transplantation, 26, 3189-3195. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq833 Taylor, G. J. (1994). The alexithymia construct: Conceptualization, validation, and relationship with basic dimensions of personality. New Trends in Experimental a nd Clinical Psychiatry, 10, 61-74. Umberson, D., Wortman, C., & Kessler, R. (1992). Widowhood and depression: Explaining long term gender differences in vulnerability. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 10-24. doi:10.2307/2136854 Watkins, E., & Teasdale, J. D. (2001). Rumination and overgeneral memory in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 353- 357. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.2.333 Watnick, S. (2007). Depression in the end-state renal disease popula- tion on dialysis. US Nephrolo gy, 1, 89-91. Watnick, S., Wang, P., Demadura, T., & Ganzini, L. (2005). Validation of two depression screening tools in dialysis. American Journal of Kidney Disease, 46, 919-924. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.006 Weissman, M. M., Bland, R. C., Canino, G. J. et al. (1996). Cross- national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA, 276, 293-299. doi:10.1001/jama.276.4.293 Yesavage, J. A., Brink, T. L., Rose, T. L. et al. (1983). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preli- minary repor t. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 37-49. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4 Zech, E., & Rimé, B. (2005). Is talking about an emotional experience helpful? Effects on emotional recovery and perceived benefits. Clinical Psychology and P sy ch o th er apy, 12, 270-287. doi:10.1002/cpp.460 Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Z imet, S. G. , & Farley, G. K. (1988). T h e multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Per- sonality Assessment, 52, 30-41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

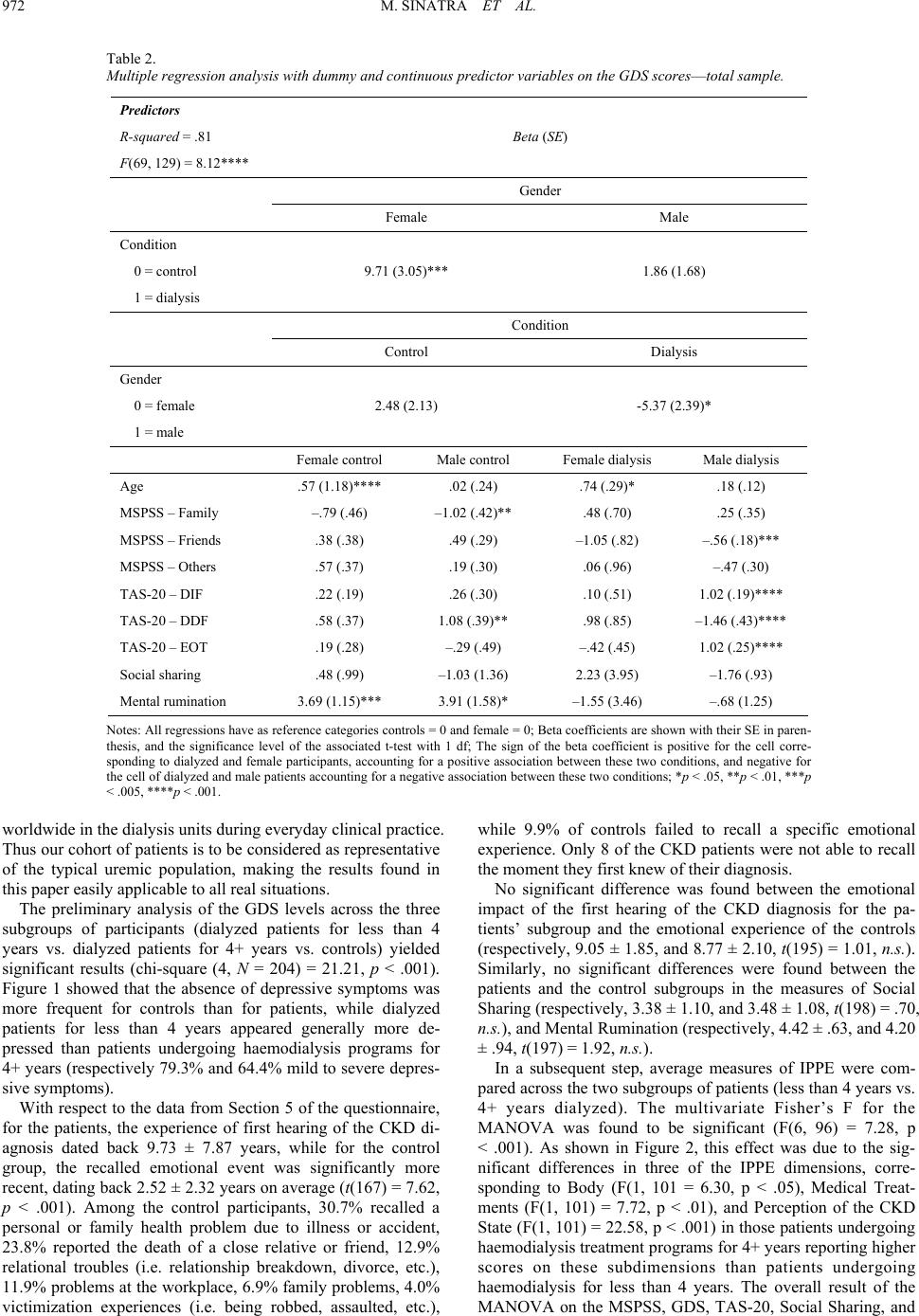

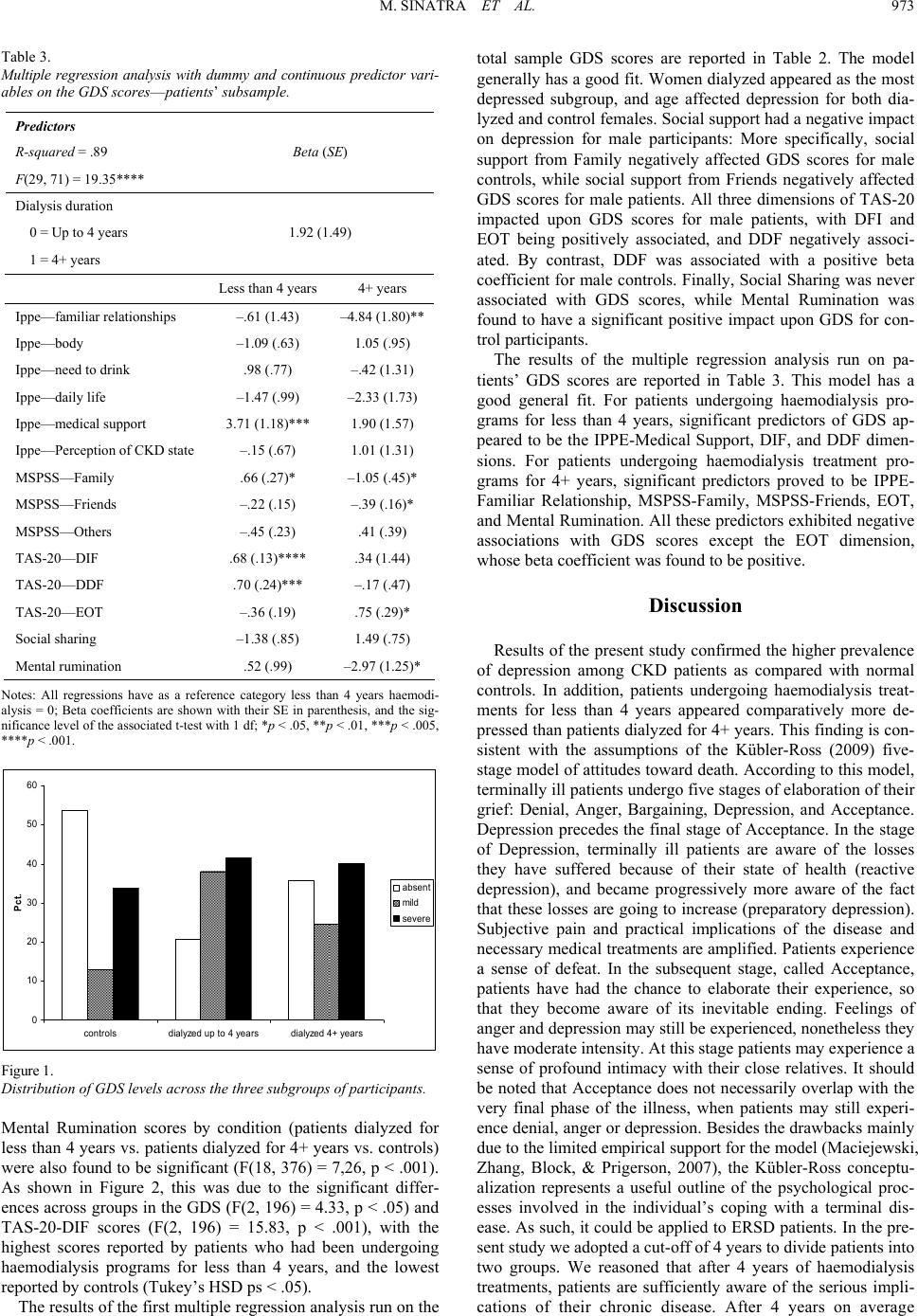

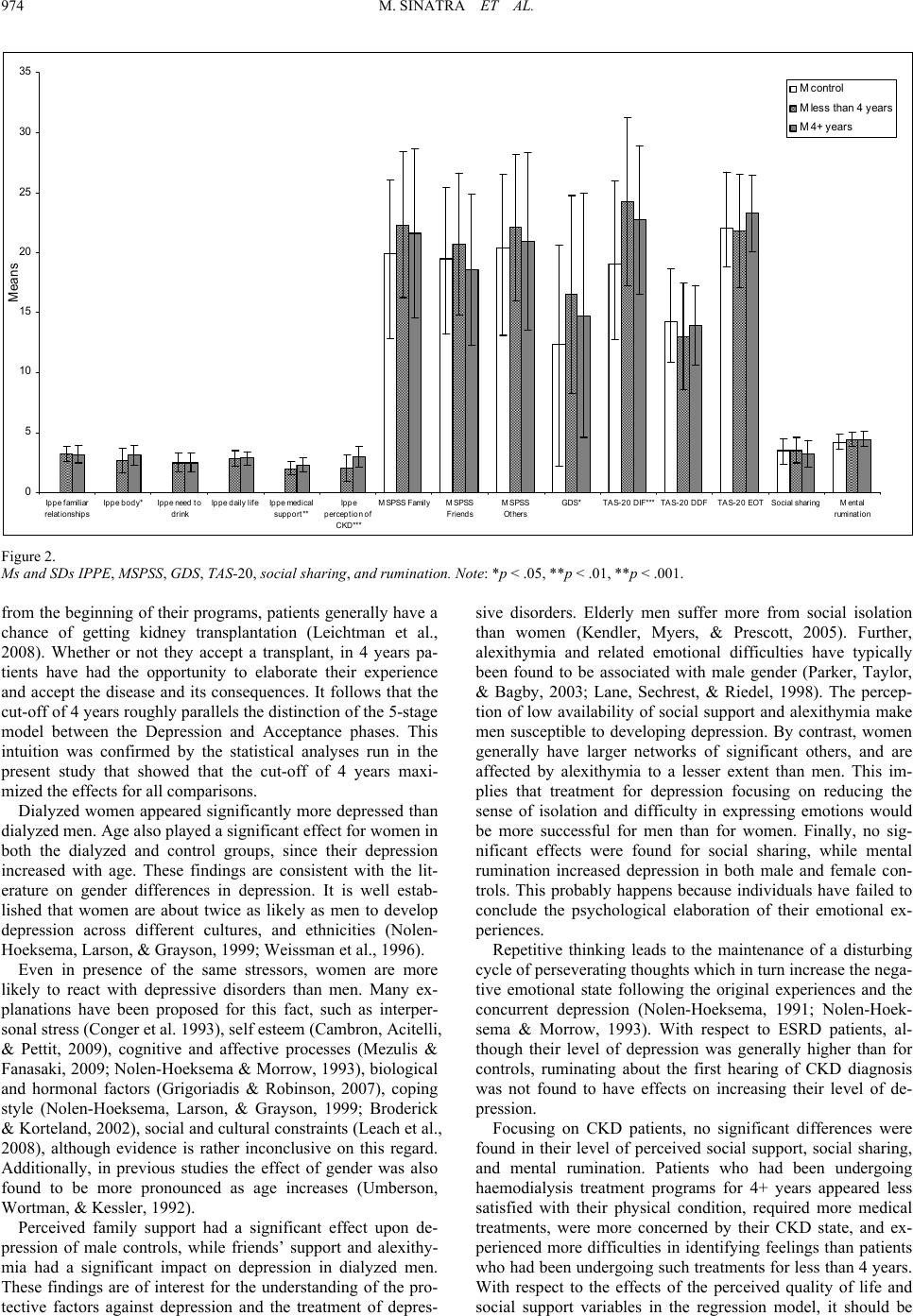

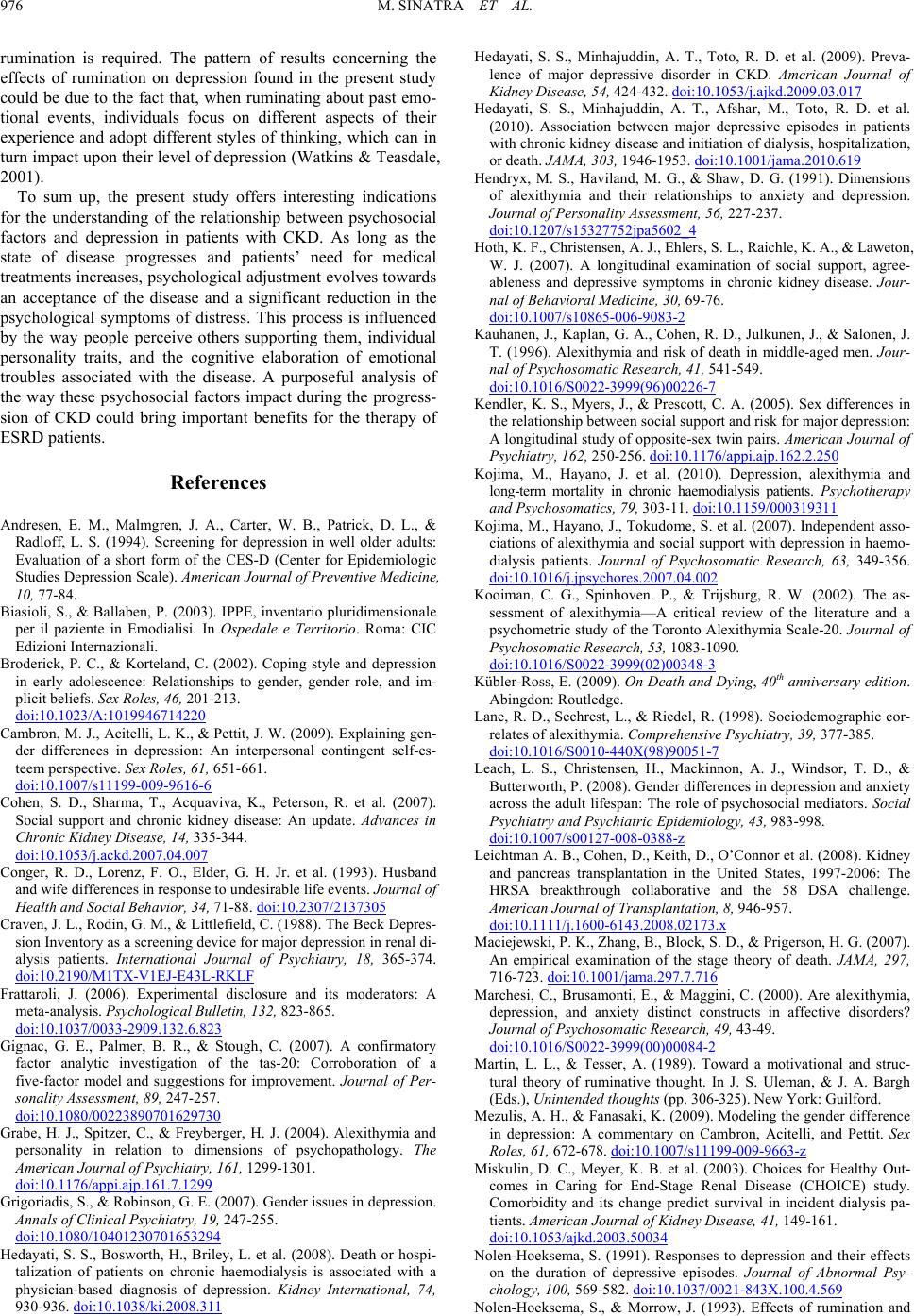

|