Health

Vol.6 No.5(2014), Article ID:43106,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2014.65048

Lay health educator role in improving cancer screening rates in underserved communities

![]()

1Public Affairs and Strategic Initiatives, Canadian Cancer Society, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

2Screening Saves Lives, Canadian Cancer Society, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

3Evaluation Consultant, Tazim Virani & Associates, Markham, Ontario, Canada; tvaconsulting@rogers.com

Copyright © 2014 Rowena Pinto et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Rowena Pinto et al. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received 21 December 2013; revised 27 January 2014; accepted 5 February 2014

KEYWORDS

Cancer Screening; Peer Support; Lay Health Educator

ABSTRACT

There are inequities in cancer screening among people living in one large province in Canada; these include breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening. The use of peer support or lay health educator models is often used in promoting health behaviours to communities. This paper outlines some of the conceptual understandings of peer support and lay health educator models and describes an application of a lay health educator program called Screening Saves Lives. The program structure and activities are discussed as well as lessons learned over a period of six years. Three key theoretical perspectives support the design of the model— Health Belief Model, Stages of Change model and PRECEDE model. The program has reached over 35,000 community members within one region using laypersons who are trained in providing tailored messages on cancer screening, supporting and follow-up. Additionally, the program has been a catalyst in identifying barriers to cancer screening and enables positive changes in the health care system. Screening Saves Lives is currently being scaled to other communities in the province.

1. INTRODUCTION

Although cancer screening tests have been in existence for many decades and have been promoted through national guidelines, there are various inequities in their access [1]. Large numbers of eligible men and women are not getting screened for cancer; thereby, they are at a disadvantage for early detection, treatment and survival. There are sub-groups of the population who are particularly disadvantaged such as those with low income, newcomer populations and women from particular ethnic groups [2] as well as communities living in rural and isolated communities who have challenges in accessing primary care [3].

Increasing attention is being paid to the barriers that are associated with the discrepancy between populations eligible for cancer screening and low screening rates [4], [5]. Interventions to increase cancer screening rates have included interventions directed at the public (e.g. mass media communication, patient education, reminder systems, decision aids, etc.); interventions directed at health care providers (e.g. practice guidelines, education, outreach, audit and feedback, local opinion leaders, etc.); and interventions directed at organizations (e.g. shared responsibility tactics and interventions, information technology, increasing clinical consultation time, etc.) [6]. It is clear that one intervention will not be adequate to make significant improvements in screening rates; hence requiring multipronged approaches [6,7].

The Canadian Cancer Society (CCS), a national, community based organization of volunteers whose mission is the eradication of cancer and the enhancement of the quality of life of people living with cancer” (www.cancer.ca), has placed a strategic priority in promoting cancer prevention and early detection by improving access to information resources; promoting access to cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment to community members; as well as providing supports to survivors and their families. In 2006, the CCS developed and implemented an innovative program to improve cancer screening rates in hard to reach communities in Northeastern Ontario using a lay health education (LHE) or peer support model. This program is referred to as the Screening Saves Lives (SSL) program. The program is based on the notion that health promotion and disease prevention can be optimized by leveraging communities’ greatest asset: the everyday relationships people have with each other (referred to as social capital). The term, “peer” has been used in the literature in various combinations with advisor, counselor, educator, facilitator, health advocate, helper, intervener, navigator, outreach staff worker; or interchangeably with “lay” combined with advisor, counselor, educator, health advisor, health worker; or with community or health (combined with advisor, educator, representative, worker); or with volunteer combined with peer educator, health worker; as well as with other titles, including outreach worker, patient advocate, buddy, health advocate (Simoni, Franks, Lehavot and Yard, 2011). With the SSL program, the peer is also referred as the Health Ambassador.

This paper provides a case study of the SSL program. The case study includes the program’s conceptual basis, its components and lessons identified through several program evaluation studies. The paper concludes the discussion of the CCS’s expansion of the SSL program as well as key considerations that shape its ongoing development.

2. DEFINING PEER SUPPORT/LAY HEALTH EDUCATOR

The notion of peer support has been in existence in many societies, over the history of humankind; it manifests in various different structures and practices. Today lay people or peers have been widely used in the health and social service sectors. Lay health educators (LHE) or peer supporters can be found in three main domains: transitional situations (e.g. breast feeding [8]); acute and chronic conditions (e.g. mental health [9], chronic disease management [10], diabetes [11]); and health promotion (e.g. HIV prevention [12], cancer screening [13] and smoking cessation [14]).

The lack of clear definitions of peer supporter or LHE has resulted in a fragmented literature and research foundation. Two key publications have attempted to bring about conceptual clarification and theoretical foundation [15,16]. Conceptual clarification is an important exercise in order to provide a transparent basis for developing, implementing and evaluating different types of peer or lay education support.

Simoni et al. (2011) identified four conceptual elements that define a peer. A peer shares some common characteristic with others in a group to whom they are a “peer”; benefits derived from the peer intervention are whole or partly a result of being a “peer”; peers do not have professional training in the area they are serving (i.e. they are lay people); and lastly, peers function through a set of intentional activities or interventions [16].

Denis (2003) conducted a concept analysis of “peer support” in the health care context. The author highlights that peer support is used in diverse settings and situations; peer support can use different modalities; there are different roles and involvement of peers with or without formal health providers; and peer support is situated within various formal or informal structures. In addition, peers can be part of embedded social networks (e.g. family members/friends or natural lay helpers such as church members, co-workers or neighbors) or created social networks (e.g. self-help groups, support groups or structured para-professional roles). As natural lay helpers, peer supporters are lay persons who are selected by community members and require minimal training. They give emotional, appraisal and informational support. In addition, through direct, buffering or mediating action, they can impact on a range of potential health outcomes (e.g. augment social network, prevent health concerns, reinforce health-seeking behaviours, decrease barriers to care, encourage effective coping, increase self-efficacy and aid in self-esteem) [15].

Peer supporters are often inter-changeably referred to as LHE. The key distinction, however, is that LHE may or may not have the direct experience of the target population; that is, they are members of the community but may not necessarily share a common health condition or concern. In either instance, such roles “are uniquely qualified as connectors because they live in the communities in which they work, understand what is meaningful to those communities, communicate in the language of the people, and recognize and incorporate social buffers (e.g., cultural identity, spiritual coping, traditional health practices) to help community members cope with stress and promote health outcomes [17]”.

3. LAY HEALTH EDUCATOR MODEL

There are three predominant versions of LHE-based interventions used in healthcare systems: didactic or oneon-one, group-based, and a combination of group-based and didactic [18]. In addition, technology based interactions are also being used such as emails, listservs, chat rooms, websites, etc. In a group-based model, LHE facilitates discussion for a group that shares similar health conditions, demographics or both. A didactic intervention model has a one-on-one format between a LHE and an individual; where the interactions could be face-toface, by telephone or internet based. A combined LHE model would consist of group-based and one-on-one methods. All three models share similar goals of encouraging individuals to adopt new behaviours that would result in positive health outcomes. Hoey, Ieropoli and White (2008) conducted a systematic review of peer support programs for people with cancer and found no difference in effectiveness between one-on-one face-to-face, oneon-one telephone, group face-to-face, group telephone and group Internet approaches [19].

In all three LHE models, the LHE provides information, emotional, and instrumental supports [20]. Information supports involve giving health promotion and practical advice on accessing programs and services. Emotional support requires having non-judgmental listening while providing gentle encouragement and empathetic response. Instrumental supports infer helping people remove barriers to health seeking behaviours. In contrast to professionally delivered services, LHE support is based upon the premise that, by virtue of having life experience and/or community affinity, they are able to provide a unique form of empathy and support to others [21].

There are many roles that LHE can have. The University of Arizona (1998) outlined seven core services of LHE from their extensive work with hundreds of community health workers [22]. These are:

1) Bridging cultural mediation between communities and the health care system;

2) Providing culturally appropriate and accessible health education and information;

3) Assuring that people get the services they need;

4) Providing informal counseling and social support;

5) Advocating for individuals and communities within the health and social service systems;

6) Providing direct services (such as basic first aid) and administering/encouraging health screening tests; and 7) Building individual and community capacity.

4. SCREENING SAVES LIVES— APPLICATION OF THE LAY HEALTH EDUCATOR MODEL

The SSL case study is described by first providing an overview of the program, outlining its theoretical foundation, historical development followed by description of its goals and objectives and how the program is structured and operated.

4.1. Overview of Program

The SSL program engages communities identified as under or never screened; that is, those communities where there is evidence of low cancer screening rates or communities that are not meeting cancer screening targets set by the Ministry of Health. Specifically, the SSL program has aligned its objectives with three cancer screening areas—breast, cervical and colorectal. These three cancer screening programs are aligned with the provincial government’s strategy on cancer prevention.

The communities are engaged at every step of the process from planning, implementation, monitoring and ongoing improvements of the SSL program. Although the SSL program has specific core components, the program is tailored based on the needs of the community and the advice provided by community members. Volunteers from target communities are recruited and trained as Health Ambassadors (a term used in the SSL program for LHE). The Health Ambassador’s primary role is to convey the importance of cancer screening, specifically, cervical, breast and colorectal cancer screening.

4.2. Theoretical Foundation

Three theoretical models were used to inform the development and implementation of the SSL program: the PRECEDE Model [23]; the Health Belief Model [24]; and the “Stages of Change” Transtheoretical Model [25].

1) Health Belief Model suggests that changes in health-related behaviour are based on the beliefs people have on how susceptible they are to a health threat, how severe they believe the threat to be, their perception of barriers to taking action to address the threat and their perceived benefits of taking such action.

The Health Ambassadors are provided specific training on what is already known about the target group’s beliefs, barriers and enablers in relation to cancer screening. They are also encouraged to use their own lived experience to provide a greater understanding of how community members might perceive cancer screening messages. It is this combined knowledge that helps the Health Ambassadors to tailor culturally sensitive messages for sub-groups within their community as well as be cognizant of the unique barriers, challenges and opportunities that community members may face. For example, knowing about a recent death in the community as a result of cancer will have different impacts on different people; some may be fearful and anxious while others may have high readiness to listen and take action. Assessing a person’s health beliefs becomes an essential part of communicating cancer screening messages.

2) Stages of Change Transtheoretical Model suggest that there are five stages people go through in behaviour change.

a) Pre-contemplation: stage in which people who have never thought about cancer or cancer screening, and or lack the experience to do so;

b) Contemplation: stage in which people who have thought about getting cancer screening, but have not;

c) Preparation: stage in which people are making an appointment or who have a clear plan in getting screened;

d) Action phase: stage in which people have gotten screened and may be encouraging others to get screened;

e) Maintenance: stage in which having the same healthseeking behaviour (cancer screening) continue on a regular basis.

The cancer screening messages are tailored by the Health Ambassador for an individual’s particular situation and starting point. For example, individuals who have never thought about cancer screening are given essential information and plan to conduct follow up; while a person who has already thought about screening is provided reinforcing messages and offers of support to arrange an appointment or practical supports to accessing screening programs and services.

3) PRECEDE Model identifies three sets of factors that promote or impede an individual’s action or behaviour:

a) Predisposing factors such as personal beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes about breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening; these factors are more specifically understood using the Health Belief Model;

b) Enabling factors related to the health care system such as type and number of providers and proximity to screening facilities;

c) Reinforcing factors my include reminder systems to keep an appointment for screening.

The PRECEDE Model provides the rationale for the need to pay attention to factors external to the individual that influence screening behaviours. For example, a key role of the Health Ambassadors is to assist in identifying barriers and facilitators that impact community member’s cancer screening behavior. Where Health Ambassadors are able, they support individuals and groups to access cancer screening such as organizing cancer screening appointments or advocating SSL program leaders and/or partners to address identified barriers.

4.3. Program Goal

The goal of the SSL program is to increase screening rates for breast, cervical and colorectal cancers by using Health Ambassadors, volunteers who are trained “natural helpers”. A “natural helper” was defined as a person who is likely to feel comfortable asking people in their lives (e.g. relatives, friends, neighbours, co-workers) what they know about the early detection of breast, cervical and colorectal cancers, listen to their concerns, tell them about available services, and talk to and encourage them to be screened.

The vision for the SSL program is grounded in the CCS mission and the targets set in the action plan, “Cancer 2020”. The action plan calls for 90% participation of eligible women to get breast screening; 95% of eligible women to get cervical screening; and 90% of eligible women and men to get colorectal screening.

4.4. Program Objectives

The SSL program’s objectives are to:

• Develop the knowledge base in the community regarding the value for cancer screening;

• Increase the number of men and women who are screened;

• Identify and reduce barriers to cancer screening.

The essence of the program is to conduct outreach activities, identify and recruit community members who can be trained as Health Ambassadors. These Health Ambassadors (volunteers) are supported by a paid program coordinator to reach other community members with health promotion messages related to cancer screening as well as supports to enable access to the health care services such as mammograms for breast screening, pap tests for cervical screening and fecal occult blood test for colorectal screening.

4.5. Program Components

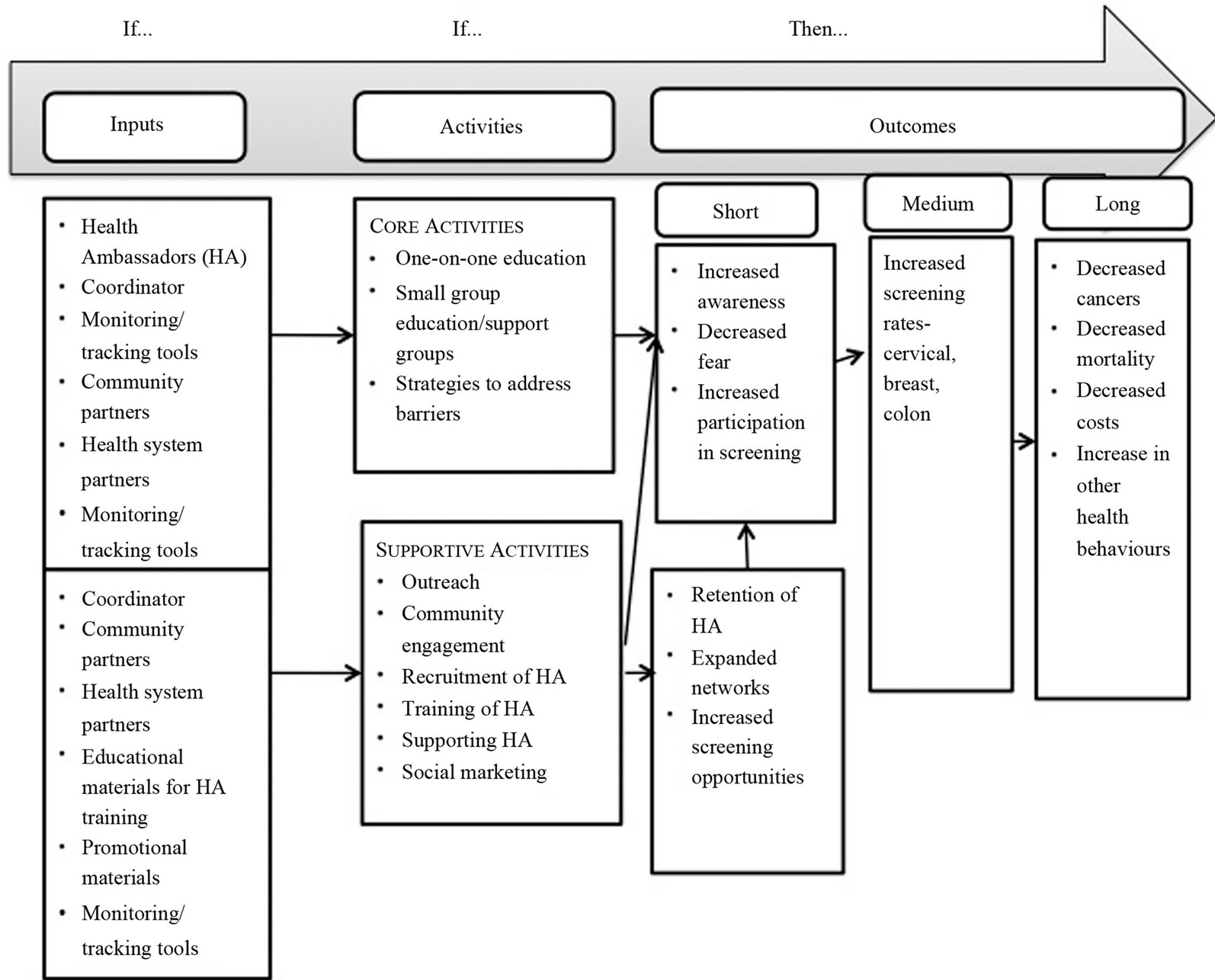

The core element of the SSL program revolves around the support that Health Ambassadors provide community members through one-on-one or small group discussions and education as well as identifying and addressing barriers to screening (See Figure 1). Some barriers to screening may be addressed directly by the Health Ambassadors while other barriers are addressed through advocacy work and by health system and community partners. These activities occur as part of the Health Ambassador’s daily interactions with those who are in their network and through more intentional forums such as being present at a health fair booth or other community organized activities. To increase the awareness of cancer screening in the community and to support the efforts of the Health Ambassadors, specific social marketing strategies are planned and implemented concurrently. Such strategies are specific to the communities in which the Health Ambassadors live and involve health system partners who leverage the presence of these volunteers to customize the messages for their peers. For example, Health Ambassadors will contact their peers to attend a cancer screening blitz that a health system partner is marketing.

To structure and support the key activities of the Health Ambassadors, the SSL program has the following:

• A full time SSL Coordinator (paid staff), who provides the structural, operational and monitoring functions to support the work of the Health Ambassadors.

• Recruitment, orientation, and ongoing training of Health Ambassadors.

• Development of partnerships with community groups, organizations and service providers.

• Collaboration with health system and community partners to spread key messages related to cancer screening.

Figure 1. Screening Saves Lives logic model.

• Monitoring systems to keep track of the program’s impact in terms of reach as well as barriers faced by community members in accessing cancer screening.

4.6. Program Implementation

The implementation of the SSL program involves three sets of activities. These are:

1) Community outreach and engagement: Using a community development approach, the program seeks to engage community members in defining relevant aspects of how the SSL program can be customized to address the needs of targeted communities. A local SSL Advisory Committee is established and with their support Health Ambassadors are recruited; and activities are planned to reach people in the community who are under or never screened for cancer.

2) Orientation and support of Health Ambassadors:

All Health Ambassadors are provided the common understanding of their roles and are supported to acquire the required knowledge and tools as well as how to address barriers to screening. Ongoing support is provided by the SSL Coordinator to all Health Ambassadors to ensure the Health Ambassador’s issues and concerns are addressed in a timely manner, barriers to screening that are identified are appropriately addressed, and to foster ongoing commitment of the volunteers.

3) Partnerships with health system and community partners: the SSL program is situated so that partners can leverage the Health Ambassadors. Specific activities will depend on the local needs and initiatives of the partners. Additionally, barriers identified by LHE may be addressed by these partners. For example, solutions may include providing screening services in locations that are more accessible for the community; provision of transportation; and language translation at the time of screening.

5. LESSONS LEARNED

Over the first six years of the SSL program, a number of key lessons were gathered that support the continuous improvement and evolution of the program. One of the most important findings is that the SSL program has a core component that has remained the same; that is the role of the Health Ambassador. Recruiting highly committed volunteers from the grassroots takes continuous effort at networking and using a “word of mouth” approach. Reaching and recruiting volunteers from specific target groups is an ongoing challenge and needs to be assessed and reassessed over time. Although the Health Ambassadors are recruited primarily for one-on-one and small group peer support, it is necessary to have a contingent of Health Ambassadors who are comfortable attending health fairs to present to larger groups, provide information to community members who visit the booths, as well as conduct outreach in the broader community. Providing opportunities for monthly contacts between the Coordinator and Health Ambassadors has been critical in ensuring their ongoing engagement. These contacts can occur through monthly meetings, continuing education sessions, telephone chats or informal get-togethers. Providing practical suggestions and supports to Health Ambassadors ensures that these volunteers themselves are not faced with barriers to spreading cancer screening messages. Health Ambassadors also value meeting other Health Ambassadors and exchange their experiences and share their lessons learned.

The implementation of the SSL program; however is highly dependent on the local context and needs of the target communities. The recruitment of a strong and connected Community Advisory Group in each community was critical to the success of the SSL program. Having a flexible approach, supportive and engaged community, and an implementation pace that is set by the community are all important lessons. The program cannot be “forced” onto a community.

The selection of the target communities was critical and required consideration of a number of factors including local cancer screening rates, access to screening, cultural views of cancer and screening, volunteer culture and the physical geography of the community. These factors drive the types of interventions employed to conduct community outreach and recruitment of Health Ambassadors as well as a mix of one-on-one, group and large community events that were planned. In some communities, the use of small to medium size group sessions where screening messages are shared in an interactive and fun manner has been particularly helpful to decrease fear and normalize the cancer screening messages.

The role of the SSL Coordinator was instrumental in advancing the objectives of the SSL program. The Coordinator has knowledge of and extensive connections or networks in the target communities including understanding of the unique needs of the community. The Coordinator needed to have excellent interpersonal skills, welldeveloped organization skills with the ability to balance priorities, and be flexible to the needs of the community. Having stability in this role has been essential for the continuity and expansion of the SSL program.

Allowing sufficient time for recruitment, screening and training of Health Ambassadors was essential as well as flexibility in the implementation of training. The training ensures that all volunteers have the knowledge and confidence to promote cancer screening and to represent the CCS’s mission and values. Ongoing volunteer support is also extremely valuable in order to maintain high activity levels of volunteers.

The SSL program, by virtue of its grassroots and community development principles, has allowed the engagement of numerous formal and informal partnerships. These partnerships have been a critical vehicle through which some of the identified barriers to cancer screening have been addressed. For example, in one community, community members who are obese had barriers in getting screened because clinic examination tables were not suitable. Through the advocacy by the Health Ambassadors and engagement with the local Public Health Unit, proper size examination tables were purchased.

As the SSL program progressed, it was important to evaluate the achievement of SSL objectives and targets and set new targets; this may need to be done every two to three years depending on the size of the target community. With new community targets, it is necessary to assess if there need to be the recruitment of new community representation on the Advisory Committee and recruitment of new Health Ambassadors that reflect the new target communities. A balanced approach is needed in tracking activities, outputs and outcomes from events, small group sessions and one-on-one approaches; over emphasis on one method over another could unintentionally lead the program to focus on the highly monitored activities only. When considering tracking activities, it was important to keep in mind that Health Ambassadors required simple and easy to use documentation tools that also had minimal impact on their time.

Assessing the impact of SSL program on cancer screening rates is difficult; however, the impact of the program on increasing participation numbers has been highly successful. For example, over a six year timeframe of the SSL program, over 35,000 individuals were reached. Using qualitative methods, as well as self-reporting strategies through the volunteers, can help to build a rich database of barriers, enablers and successful outcomes. Conducting and monitoring follow up actions including repeat contacts with community members and six-month follow up phone calls to those who have participated in a formal education session are some strategies to assess the impact of SSL program activities.

6. KEY CONSIDERATIONS IN THE EXPANSION OF THE SSL PROGRAM

The CCS has received significant support in Ontario from numerous communities and groups to expand the SSL program to other communities. At the time of the publication, the SSL program is expanding the program in Northern Ontario and has begun the implementation of the program with the South Asian communities in the Peel Region of Ontario and the lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, transgendered, queer (LGBTQ) communities in three major cities. The following have been key considerations in the expansion of the SSL program based on the lessons learned:

• Identification of key stakeholder groups and in-depth discussions with each group to identify the most appropriate partners and individuals to work with;

• Upfront identification and allocation of resources to support the required infrastructure and time needed for planning and implementation;

• Working with Community Advisory Groups to tailor the SSL program to the local context of the target communities. This includes having a clear understanding of the community profile, key sub-target groups, available data on screening rates, and existing activities in the area of cancer screening in these communities; as well as better understanding of the cultural, linguistic and other unique factors of the target communities. Leveraging existing activities, programs or initiatives has been valuable in building partners but also ensuring efficient use of scarce resources while reducing duplication of effort and potential confusion in the communities.

• Identification and engagement of an evaluation consultant to support the development of the evaluation of the expanded SSL programs and development of common tracking tools. The early involvement of the consultant has also allowed the program to develop a clear and concise logic model to describe the tailored SSL program for specific target groups.

7. CONCLUSION

The SSL program has received strong endorsement from a wide range of stakeholders, partners and community members. It has a robust theoretical foundation, a sound tested proof-of-concept, proven sustainability in several communities for over six years and an intuitive acceptance that makes the program very attractive to community members and ready to scale. There are continuing lessons that are being captured through program evaluation and formal research studies; this will continue to inform how the SSL program responds to different community contexts.

REFERENCES

- Cancer Quality Council of Ontario (2013) Screening. http://www.csqi.on.ca/cms/One.aspx?portalId=126935&pageId=127643

- Bierman, A.S., Angus, J. and Ahmad, F. (2009) Access to health care services. Project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidence-Based Report 2009, 10.

- Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (2013) Rural and northern healthcare framework/plan. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ruralnorthern/report.aspx

- Hanson, K., Montgomery, P. and Bakker, D. (2009) Factors influencing mammography participation in Canada: An integrative review of the literature. Current Oncology, 16, 65-75.

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (2010) Strategies to maximize participation in cervical screening in Canada. http://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/sites/default/files/Pan_Canadian_Cervical_Cancer_Screening_Collaboration_Catelogue_Final_English.pdf

- Brouwers, M.C., De Vito, C. and Bahirathan, L. (2011) Effective Interventions to facilitate the uptake of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening: An implementation guideline. Implementation Science, 6, 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-112

- Bailey, T.M., Delva, J. and Gretebeck, K. (2005) A systematic review of mammography educational interventions for low-income women. American Journal of Health Promotion, 20, 96-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-20.2.96

- Lewin, S., Dick, J., Pond, P. and Zwarenstein, M. (2005) Lay health workers in primary and community health care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1.

- Ireys, H.T., Chernoff, R. and DeVet, K.A. (2005) Maternal outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of a community-based support program for families of children with chronic illnesses. Archives Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 155, 771-777. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.155.7.771

- Griffiths, C., Foster, G. and Ramsay, J. (2007) How effective are expert patient (lay led) education programmes for chronic disease? BMJ, 334, 1254-1256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39227.698785.47

- Heisler, M. (2007) Overview of peer support models to improve diabetes self-management and clinical outcomes. Diabetes Spectrum, 20, 214-221. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.20.4.214

- Latkin, C.A., Sherman, S. and Knowlton, A. (2003) HIV prevention among drug users: Outcome of a networkoriented peer outreach intervention. Health Psychology, 22, 332-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.332

- Mock, J., McPhee, S.J. and Nguyen, T. (2007) Effective lay health worker outreach and media-based education for promoting cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1693-1700. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.086470

- English, K.C., Merzel, C. and Moon-Howard, J. (2010) Development of a lay health advisor perinatal tobacco cessation program. Journal of Public Health Management Practice, 16, E9-E19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181af6387

- Dennis, C.L. (2003) Peer support within a health care context: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 40, 321-332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00092-5

- Simoni, J.M., Franks, J.C., Lehavot, K. and Yard, S.S. (2011) Interventions to promote health: Conceptual considerations. American Orthopsychiatric Association, 81, 351-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01103.x

- Centre for Disease Control (2011) CDC’s Division of Diabetes Translation Community Health Workers. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/projects/pdfs/comm.pdf

- Webel, A.R., Okonsky, J. and Trompeta, J. (2010) A systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-based interventions on health-related behaviors in adults. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 247-253. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.149419

- Hoey, L.M., Ieropoli, S.C. and White, V.M. (2008) Systematic review of peer support programs for people with cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 70, 315-337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.016

- Skea, Z.C., MacLennan, S.J. and Entwistle, V.A. (2011) Enabling mutual helping? Examining variable needs for facilitated peer support. Patient Education and Counselling, 85, 120-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.032

- Legg, M., Occhipinti, S. and Ferguson, M. (2011) When peer support may be most beneficial: The relationship between upward comparison and perceived threat. Psycho-Oncology, 20, 1358-1362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1862

- University of Arizona & Annie E. Casey Foundation (1998) The National Community Health Advisor Study: Weaving the Future. http://www.aecf.org

- Crosby, R. and Noar, S.M. (2011) What is a planning model? An introduction to PRECEDE-PROCEED. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 71, S7-S15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00235.x

- Austin, L.T., Ahmad, F. and McNally, M.J. (2002) Breast and cervical cancer screening in Hispanic women: A literature review using the health belief model. Women’s Health Issues, 12, 122-128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1049-3867(02)00132-9

- Prochaska, J.O. and Velicer, W.F. (2008) The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12, 38-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38