Health

Vol.5 No.4(2013), Article ID:29883,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.54094

Priority setting in health care: Attitudes of physicians and patients

![]()

School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Jacobs University, Bremen, Germany; *Corresponding Author: m.schreier@jacobs-university.de

Copyright © 2013 Jeannette Winkelhage et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 2 March 2013; revised 1 April 2013; accepted 10 April 2013

Keywords: Prioritization; Patients; Physicians; Qualitative Research; Interviews; Semi-Structured; Content Analysis

ABSTRACT

Background: The opinion of physicians clearly counts in prioritizing health care, but there is little information on the rationales underlying treatment decisions and whether these rationales are accepted by patients. Objective: To compare physicians and patients regarding their understanding and use of therapeutic benefit and treatment costs as criteria for prioritizing health care. Methods: Seven physicians and twelve patients were purposefully selected to yield a heterogeneous sample. Participants were interviewed face-to-face, following a semi-structured topic guide comprising three scenarios that focused on interventions with low or unproven therapeutic benefit and high costs, respectively. For data analysis we used qualitative content analysis. Results: We found that patients and physicians differed in their understanding of therapeutic benefit, their expectations of what medicine can do and their use of costs as criteria for prioritizing health care. Physicians were less likely to assess a certain intervention as effective, and they less often accepted upper funding limits in health care. Unlike the physicians, patients raised non-medical aspects in decision making such as the patient’s consent and social inequalities. Conclusions: The revealed differences point toward the necessity to strengthen the doctor-patient communication, to improve information for patients about the possibilities and limits of health care and to gain a deeper understanding of their attitudes, wishes and concerns to reach an agreement by physicians and patients on the treatment to be implemented.

1. INTRODUCTION

As a consequence of budget constraints in all western health care systems, priority setting seems inevitable. In several countries, such as Great Britain, New Zealand and Israel, prioritization guidelines for the allocation of health care resources have been developed; in this, criteria such as therapeutic benefit and costs played an important role [1]. However, in practice at the doctor- patient level, physicians decide whether a certain treatment is effective and cost-worthy or not. But do patients share physicians’ opinions about health care priorities? Do both have similar attitudes regarding treatment effectiveness and costs in patient care? This question is crucial: If physicians base their decisions on criteria and rationales that are not shared by patients, patients might perceive these decisions to not be in their best interest. This perception in turn can undermine patients’ trust in the doctor-patient relationship which is important for patient satisfaction and adherence [2,3].

Several studies show that laypersons as well as physicians strongly support the therapeutic benefit as a criterion for prioritizing medical services [4-6], whereas priority setting on the basis of costs is less accepted by both groups [4,7]. However, studies comparing the attitudes of physicians and the general public regarding costs and therapeutic benefit for prioritizing health services show some differences between these two groups [8-10]. For instance, Ryynänen et al. [9] found that physicians were more willing to accept the restriction of expensive health care than the general public; Oddsson [10] reported that physicians were more likely to prioritize an effective outcome than the general public.

One drawback of all these studies is their focus on the comparison between physicians and laypersons in general. But medical decision making mostly occurs between the physician and the patient. Patients differ from the general public because the scarcity of medical services affects them directly. They differ from the physicians insofar as they are assigned a passive role whereas physicians act as gatekeepers who are held responsible for containing health care costs [6]. Moreover, patients are personally affected by their disease but do not normally have the expertise to cope with it. They are vulnerable and depend on the goodwill and the competence of the physician who, in contrast to the patients, performs a professional role and has expert knowledge [2]. These different positions and asymmetries might well result in additional differences concerning the role of treatment effectiveness and costs in health care, over and above differences between physicians and the general public that were revealed by previous studies.

Moreover, all the above studies have used quantitative methods such as closed-ended questionnaire items in the survey-type studies. These methods typically allow for the breadth and generalizability, providing information on attitudes of large samples of a variety of items. But the restructured format makes it difficult to consider the various rationales underlying these decisions. Also, closedended items are based on the assumption that all participants share the same understanding of pertinent concepts. But there is some evidence that laypersons and physicians differ in their understanding of criteria such as therapeutic benefit and costs [7,11]. The findings of the above quantitative studies might therefore obscure additional differences between physicians and laypersons concerning priority setting in health care. To reveal these, more in-depth qualitative methods are required.

In this article we present an exploratory interview study where we juxtapose the attitudes of a sample of German physicians and patients concerning therapeutic benefit and costs as criteria for prioritizing health care. The study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the attitudes of physicians toward therapeutic benefit and cost as criteria for prioritizing health care?

RQ2: What are the attitudes of patients toward therapeutic benefit and cost as criteria for prioritizing health care?

RQ3: What are the similarities and differences between physicians’ and patients’ attitudes toward therapeutic benefit and cost as criteria for prioritizing health care?

2. METHODS

The present study is part of an exploratory interview study on prioritizing health care with members of six different interest groups [12]. Here, we report only parts of the results comparing physicians and patients.

2.1. Design

We implemented a qualitative survey design [13]. Unlike the quantitative survey, which aims at inferences about the distribution of characteristics in a population, the qualitative survey is concerned with representing the diversity of a given phenomenon.

2.2. Case Selection

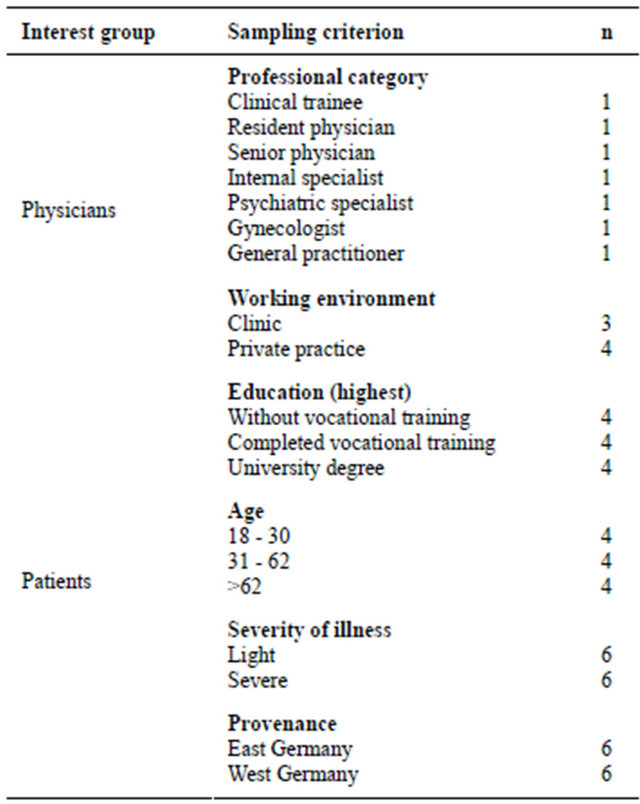

The qualitative survey requires a purposive diversity sample [13]. In line with this requirement, we purposefully selected the participants according to predefined criteria [14] that were chosen so as to yield a maximally heterogeneous sample. To this end, we implemented a strategy of stratified purposive sampling [15]. We included physicians from different professional categories to encompass different stages in a physicians’ career as well as a wide range of professional specializations. Moreover, we selected physicians from different working environments (clinic or private practice). In the patient group we included individuals who suffered from an illness that requires medical treatment. We used the term severity of illness to encompass a variety of physical and mental as well as acute and chronic medical conditions at different stages. Moreover, we selected individuals that were as diverse as possible based on their educational level [16], age, provenance (former East or West Germany) and severity of illness. We identified physicians who met the above criteria through the internet and contacted them by telephone; patients were recruited via their physicians. In addition, we incorporated an element of snowball sampling by asking (potential) interviewees to propose other potential participants. A total of seven physicians (2 women, 5 men) and twelve patients (5 women, 7 men) from different cities in Germany participated in the study. The physicians were between 25 and 68 and the patients between 21 and 69 years old (mean = 44, and 47 years, respectively) (for more details on the sample see Table 1).

2.3. Data Collection

For data collection we used semi-structured interviews. Here we focus on that part of the interview guide that is concerned with priority setting of interventions, taking into account costs and health care effectiveness. This part comprised three sections.

In the first section we addressed interventions with low therapeutic benefit by confronting the participants with an actual case: Terri Schiavo, a patient from Florida, USA, suffered from massive brain damage; she was in a coma for 15 years and died after her feeding tube was disconnected [17]. We asked the participants about their opinion concerning the termination of Terri Schiavo’s life support. We chose the Schiavo case to confront the

Table 1. Sample composition of the interview study.

participants with a realistic decision-making situation in a medical context that is concerned with both therapeutic benefit and ethical issues. The second section focused on evidence-based medicine. We asked the participants whether public health care should stop covering treatments that are effective from the perspective of medical experts but do not meet the criteria of evidence-based medicine [18]. Here our concern was with the role of therapeutic benefit and with participants’ concepts of effectiveness and evidence. The third section focused on the acceptance of upper funding limits. We confronted the participants with a rule adopted in the United Kingdom according to which the costs of cancer therapy must not exceed 30.000 Euro per life year gained by administering the therapy. Participants were asked for their opinion about implementing this type of rule in Germany. The rule was adapted from the English QALY (see www. nice.org.uk) and simplified to make it easier to understand, with a focus on costs, not on different aspects of therapeutic benefit (which are already covered by the second subsection).1 We conducted the interviews in locations of the participants’ choice. All of the physicians and two patients were interviewed in the work place. The majority of the patients were interviewed at home. Prior to each interview, participants signed a consent form. Interviews lasted between 32 and 128 minutes (mean = 66 minutes). We recorded and fully transcribed the interviews. At this point we removed all identifying information.

2.4. Data Analysis

We used qualitative content analysis to summarize and to systematize the interview material [19], identifying relevant themes and categorizing them into main categories and subcategories. Main categories were mostly concept-driven and derived from the interview questions. Subcategories were data-driven and were based on a thorough reading of the material: Whenever we identified a pertinent theme that was mentioned by two or more participants, we added it as a new subcategory. For this first version of the coding frame, we conducted a pilot coding with two independent researchers categorizing the same four transcripts. Coding consistency was 87.1% across main and 73.9% across subcategories for the pilot version of the frame and 96.6% across main and 83.7% across subcategories for the revised, final version of the frame. During the main coding, one third of the transcripts were again categorized by two independent researchers. Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion, and one researcher categorized the remaining material. To support data analysis, we used the computer software MAXQDA (VERBI GmbH, Berlin/Marburg).

3. RESULTS

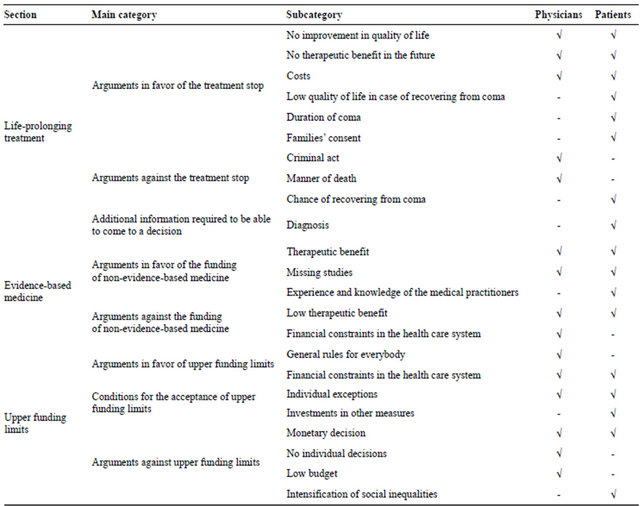

In presenting our findings, we are concerned with the categories and subcategories identified in the material, both within and across stakeholder groups (for a summary of main categories and subcategories by question and stakeholder group see Table 2). Category names are given throughout in italics. Coding frequencies are not relevant considering the small sample size and will not be reported.

3.1. Section 1: Life-Prolonging Treatment

A majority of the physicians supported the termination of the life-prolonging treatment based on two different aspects of therapeutic benefit: First, most of them believed that the treatment did not so much provide a benefit in terms of improving quality of life as extend Schiavo’s suffering (no improvement in quality of life). Second, some physicians claimed that Schiavo’s health status was unlikely to change (no therapeutic benefit in the future). Most of the physicians also broached the issue of costs as an argument in favor of the feeding stop; they considered the costs to be too high in view of budget constraints in the health care system. Nevertheless, those who argued along these lines also underlined that costs were secondary to other criteria, especially

Table 2. Main arguments of physicians and patients in the interview study.

Ö = mentioned; - = not mentioned.

therapeutic benefit, and therefore not crucial:

“If, at high expense, someone’s life can be saved permanently, the costs are of minor interest. However, if based on prior medical experience the patient’s survival is unlikely, the initial costs of treatment are already too high.”2 Those physicians who argued against the removal of the feeding tube did so primarily on moral grounds, stressing that humans do not have the right to end the life of others (criminal act):

“I think humans do not have the right to end someone else’s life, which one would be doing by removing the feeding tube. She is still alive, her vital functions are stable.”

Medical or economic criteria played no role in the physicians’ reasoning against the removal of the feeding tube.

Like the physicians, most patients of our sample supported the treatment stop, with low therapeutic benefit being the main argument (no improvement in quality of life, no therapeutic benefit in the future), followed by the issue of costs. Like the physicians, patients considered this as subordinate to other criteria; therapeutic benefit, the duration of coma and Schiavo’s consent were considered to be more important. However, in contrast to the physicians, the patients did not place this issue in the broader context of budget constraints in the health care system. Instead, they argued from a micro perspective, suggesting that the money would be better spent on patients with more promising diagnoses:

“One has to calculate how much all this is going to cost, and perhaps the money could be spent on those people who would actually benefit from treatment.”

Patients also provided some additional reasons in support of the treatment stop that were not mentioned by the physicians. A first set of reasons referred to the effects of the coma on Terri Schiavo: Patients argued that after 15 years of coma no improvement was to be expected (duration of the coma), or else that quality of life in case of a recovery from coma would be too low to warrant further treatment (low quality of life in case of recovering from coma):

“Even if it was possible to recover from coma after 15 years, she will never be of sound mind again. I think one should show mercy and terminate the treatment.”

A second type of reason introduced the family’s consent as another important criterion in favor of the feeding tube removal, bringing Schiavo’s preferences and the issue of shared decision-making into focus. Those patients who argued against the treatment stop did so primarily on medical grounds, saying that Schiavo might have recovered from coma (chance of recovering from coma). That is, unlike the physicians, they expressed some trust in the therapeutic benefit of the treatment:

“There have been cases where someone has recovered from coma.”

3.2. Section 2: Evidence-Based Medicine

The majority of physicians expressed the opinion that non-evidence-based measures should no longer be included in public health care. Most of them predominantly did so because of low therapeutic benefit, arguing that non-evidence-based measures are unlikely to result in improvement and therefore problematic:

“In general I agree that the efficacy of a treatment should be confirmed by scientific studies because there have been cases where certain treatments, preventive measures or diagnostics that looked promising were not shown to be effective after all.”

Those physicians who supported the funding of nonevidence-based medicine believed that these measures often do have an effect which current methods fail to detect (therapeutic benefit), or else that potential effects are not investigated in the first place for economic reasons (missing studies).

Unlike the physicians, the majority of patients opted in favor of public health insurance covering treatments that are not evidence-based. Three reasons predominated in their decision: First, patients considered non evidencebased measures to be effective nonetheless (therapeutic benefit):

“For some therapies, for example homoeopathy, efficacy has not yet been proven scientifically, nevertheless they are effective.”

Second, patients argued that the sheer multitude of diseases and treatment options prevents collecting scientific evidence in every single case (missing studies):

“I don’t know for what percentage of all diseases evidence-based therapies exist and for what percentage there are none. A multitude of patients would be left behind somewhere on the way.”

Third, some patients expressed full confidence in the opinion of medical practitioners, considering their experience and knowledge sufficient evidence (experience and knowledge of the medical practitioners). Those patients who decided against the funding of treatments which are not evidence-based did so because, like the physicians, they had some doubts regarding their efficiency (low therapeutic benefit):

“For example traditional healing…some people believe that it is effective, some people say it is effective, others say it is not effective. For me it is OK that it is not funded by the community.”

3.3. Section 3: Upper Funding Limits

The majority of the physicians were opposed to adopting the English rule which introduces an upper limit to the funding of cancer treatments. In the context of the life-prolonging treatment scenario, physicians had mentioned costs as an important reason for implementing a treatment stop. Where cancer treatment is concerned, however, most physicians were highly critical of making a medical decision depend on financial reasons alone (monetary decision). In this they argued from a moral perspective; one physician explicitly called the rule “inhumane”: Two physicians additionally criticized equal treatment of patients by implementing general rules like the English one, stressing the individual nature of each patient’s situation (no individual decisions). Those physicians who finally decided in favor of the English rule based their decision on a variety of reasons. One physician decided in favour of the rule precisely because of financial reasons, arguing that priorities are necessary in the health care system (financial constraints in the health care system):

“If this money could be spent more reasonably elsewhere, other than extending someone’s life by one year, then I would say that this is worth more.”

Other physicians agreed to the rule, provided that it was modified, for example by allowing for exceptions (individual exceptions) or by raising the financial limit (low budget). The latter physician also argued that general rules could support physicians in making treatment decisions and that such rules could prevent physicians from making decisions based on implicit criteria or sympathy (general rules for everybody):

“Maybe physicians have to be protected somewhat and supported in decision making by fixing an amount. So that no one will be able to say: ‘Well she is a mother, I like her, she should have this treatment’.”

In contrast to the physicians, the majority of the patients endorsed the rule, some of them mentioning the necessity to save money in the health care system. However, in most cases the determining factor for accepting the rule was not the cost pressure but two conditions to be met: First, patients endorsed the rule provided that the funds that are saved be invested in measures that would benefit more people (investments in other measures). Second, individual exceptions should be possible; i.e. some patients argued in line with the physician who also supported the rule on this condition. Those who argued against the rule primarily did so on the grounds that a patient’s fate must not depend on financial considerations alone (monetary decision). Like the physicians, they took a moral stance, but they expressed this in far more emotional terms: Several patients described the rule as “terrifying”, “macabre” or “intolerable”:

“I would say such regulations are perverse… to measure one year of a human life in terms of money…I find this unthinkable. I think society should go to any lengths to help everyone…at any cost.”

Apart from this moral concern, patients worried that with upper funding limits, only the rich would be able to afford costly treatments (intensification of social inequalities).

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In the study reported here we used a qualitative approach to investigate in detail decisions and rationales used by patients and physicians regarding the limitation of treatments with problematic or unproven therapeutic benefit and high costs, respectively.

Our first research question concerned the attitudes of physicians toward therapeutic benefit and cost as criteria for prioritizing health care. The physicians in our sample clearly considered therapeutic benefit an important criterion for prioritizing health care. They supported the termination of the life-prolonging treatment because of its low therapeutic benefit and most of them found nonevidence-based measures not effective enough to be included in health care. Treatment costs were seen to be secondary to other criteria and therefore, not crucial for prioritizing health care. In the life-prolonging treatment section costs gained in importance when participants assessed therapeutic benefit as low. Concerning upper funding limits the physicians typically emphasized that medical interventions must not depend on costs alone; that is why most of them did not accept upper funding limits.

In our second research question, we were concerned with the attitudes of patients toward these same criteria. The patients in our sample also considered therapeutic benefit an important criterion for health care priority setting. Most of them stated that the life-prolonging treatment does not provide enough therapeutic benefit to be maintained, and in the evidence-based medicine section the majority of the patients supported the funding of nonevidence-based measures, typically arguing that these measures are effective. Costs were considered as subordinate to other criteria, such as therapeutic benefit. Upper funding limits for a certain treatment were only accepted if the saved money would be invested in treatments that would benefit more people.

Our third research question relates to the comparison between physicians and patients concerning their attitudes regarding the importance of therapeutic benefit and costs as criteria for prioritizing health care. The results show many similarities between the attitudes of the two groups. Both considered therapeutic benefit as an important criterion for priority setting decisions, whereas treatment costs were seen as secondary to other criteria. However, some differences emerged concerning the understanding and use of therapeutic benefit and treatment costs for prioritizing health care services. The physicians in our sample were more critical of the notion of therapeutic benefit than the patients. For instance, in the lifeprolonging treatment scenario physicians ruled out the possibility that the patient might recover from coma, whereas some patients expressed trust in the potential therapeutic benefit of the treatment, even after a time period of 15 years. Moreover, physicians were more likely to decide against covering non-evidence-based medicine by public health care funds because of its low or unconfirmed therapeutic benefit, whereas patients were more convinced that these measures are sufficiently effective. These results correspond to the finding by Ginsburg [7] who reported that most of the physicians in her sample complained about patients who insist on having treatments that the physicians believe are cost-ineffective or unnecessary. The different understanding of therapeutic benefit and the different expectations of what medicine can do, respectively, might be due to the fact that patients are not sufficiently informed about the benefits of different interventions, which might create unreasonable expectations. Here, a differentiated reporting on medical achievements could generate more moderate expectations. Whatever the causes of these differences might be, the building of trust between doctor and patients and increased communication might help to overcome these differences. In their interview study Skirbekk and Norvedt [20] revealed that in poor trust relations patients more often negotiate with their physician and finally obtain treatments that are not necessary. A more trusting relationship can overcome differences between patients and physicians by giving the physician the opportunity to confront the patients with perspectives that they might not have considered otherwise [2]. Sharing information and treatment preferences is a precondition to reaching a consensus on the treatment to be implemented [21].

Physicians and patients furthermore differed regarding their reasoning why costs should be considered. Whereas physicians pointed to the financial constraints in the health care system and the necessity to save money, patients mostly emphasized that money should be saved and reinvested into treating patients with a more promising diagnosis. This might reflect the pressure on physicians to contain health care costs [22]. Moreover, selfinterest might play a role here, i.e., patients might want to save money that can be reinvested in their own health care. Stronks et al. [23] also found that patients based their reasoning concerning priority setting in health care on self-interest.

Physicians and patients also differed in their final decision regarding the acceptance of upper funding limits. Although the former had pointed to the necessity to save money, they finally rejected general funding limits, whereas the latter endorsed them. The position of the physicians might originate from their responsibility toward the individual patient. In their interview study with physicians Skirbekk and Norvedt [20] revealed a type of “patient-centered partiality”: The authors found that physicians base their care on the medical and health related needs of their particular patients, not considering directions from the hospital management. However, the physicians’ reasoning in favor and against the acceptance of upper funding limits in our interview study reflects some degree of conflict between their role as patients’ advocates and as gatekeepers [20]. The physicians criticized that a general funding limit does not meet the needs of individual patients, but they also argued that priorities are necessary in the health care system. The patients’ endorsement of upper funding limits might indicate willingness to accept health care limitations and to set priorities. This again corresponds to the above mentioned study by Ginsburg [7] who reported that a majority of the participating physicians stated that patients would accept financial explanations for a decision against a certain treatment as soon as they understand that it would be a waste of resources.

Not surprisingly, patients were more likely than physicians to raise non-medical aspects when making decisions about treatments. When asked whether they agree to the termination of the life-prolonging treatment of the coma patient, some of them broached the issue of shared decision making; they emphasized that such a decision has to be discussed with the family. This finding again emphasizes the importance of the doctor-patient communication. Concerning evidence-based medicine, some patients expressed that medical practitioners should decide whether a medical treatment should be funded or not, showing full confidence in their expertise and decisions. This is in line with other studies which have found that the public want doctors to decide on prioritizing medical interventions [20]. This might seem contradictory to patients’ demand for shared decision making. However, there is evidence that treatment decisions made by physicians alone disrupt the trust in the doctor-patient relationship [3]. The claim for patient involvement in medical decision making therefore remains essential. In the context of upper funding limits, patients furthermore raised concerns about social inequalities. Such concerns must be taken into account when setting health care priorities, because a discrimination of persons with lower social status could increase health inequalities in a society [20].

The heterogeneous sample of this study spanned a wide range of patients and physicians. However, it is not statistically representative and merely served as a basis for exploring different perspectives on prioritization. Studies with large representative samples as reported, for instance, by Diederich and Schreier [4] are necessary to confirm our findings. Note, however, that those studies cannot provide information on the rationales underlying decisions. Moreover, it is possible that physicians’ and patients’ attitudes and reasoning about prioritizing in health care are shaped by factors other than the ones represented in our sampling criteria. Physicians’ specialist fields, for example, are barely represented here; with patients, prior experience with health care might play an important role. Additional in-depth qualitative studies are needed to explore the role of these and other additional factors in shaping attitudes toward decision making in health care.

To sum up: Previous studies investigating the preferences of physicians and healthy laypersons regarding medical supply have shown that both groups strongly support therapeutic benefit as priority setting criterion whereas priority setting on the basis of costs is less accepted [4,7]. In the study presented here with physicians and patients we confirmed these results. However, we also revealed differences that quantitative studies until now have failed to detect and we provided an insight into the rationales underlying different attitudes. Our findings point toward the necessity to strengthen doctor-patient communication, to improve information for patients about the possibilities and limitations of health care, and to gain a deeper understanding of their attitudes, wishes and concerns to reach an agreement by physicians and patients on the treatment to be implemented.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank those who participated in the interview study. This work has been realized within the research project “Prioritizing in Medicine” supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) grant number Di506/10-1.

REFERENCES

- Sabik, L.M. and Lie, R.K. (2008) Priority setting in health care: Lessons from the experiences of eight countries. International Journal for Equity in Health, 7, 1-13. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-7-4

- Skirbekk, H., Middelthon, A.-L., Hjortdahl, P. and Finset, A. (2011) Mandates of trust in the doctor-patient relationship. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 1182-1190. doi:10.1177/1049732311405685

- Strech, D., Danis, M., Löb, M. and Marckmann, G. (2009) Ausmaß und Auswirkungen von Rationierung in deutschen Krankenhäusern—Ärztliche Einschätzungen aus einer repräsentativen Umfrage. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift, 134, 1261-1266. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1225273

- Diederich, A. and Schreier, M. (2010) Einstellungen zu Priorisierungen in der medizinischen Versorgung: Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsbefragung. FOR 655, 27. http://www.priorisierung-in-der-medizin.de/documents/FOR655_Nr27_Diederich_Schreier.pdf

- Gallego, G., Taylor, S.J., McNeill, P. and Brien, J.A.E. (2007) Public views on priority setting for high cost medications in public hospitals in Australia. Health Expectations, 10, 224-235. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00439.x

- Hurst, S.A., Slowther, A.-M., Forde, R., Pegoraro, R., Reiter-Theil, S., Perrier, A., Garrett-Mayer, E. and Danis, M. (2006) Prevalence and determinants of physician bedside rationing: Data from Europe. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 1138-1143. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00551.x

- Ginsburg, M.E. (2000) A survey of physician attitudes and practices concerning cost-effectiveness in patient care. The Western Journal of Medicine, 173, 390-394.

- Rosén, P. and Karlberg, I. (2002) Opinions of Swedish citizens, health-care politicians, administrators and doctors on rationing and health-care financing. Health Expectations, 5, 148-155. doi:10.1046/j.1369-6513.2002.00169.x

- Ryynänen, O.P., Myllykangas, M., Kinnunen, J. and Takala, J. (1999) Attitudes to health care prioritisation methods and criteria among nurses, doctors, politicians and the general public. Social Science and Medicine, 49, 1529- 1539. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00222-1

- Oddsson, K. (2003) Assessing attitude towards prioritizing in healthcare in Iceland. Health Policy, 66, 135-146. doi:10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00211-7

- Berney, L., Kelly, M., Doyal, L., Feder, G., Griffiths, C. and Jones, R.I. (2005) Ethical principles and the rationing of health care: A qualitative study in general practice. British Journal of General Practice, 55, 620-625.

- Heil, S., Schreier, M., Winkelhage, J. and Diederich, A. (2010) Explorationsstudien zur Priorisierung medizinischer Leistungen: Kriterien und Präferenzen verschiedener Stakeholdergruppen. FOR655, 26. http://www.priorisierung-in-der-medizin.de/documents/ FOR655_Nr26_Heil.pdf

- Jansen, H. (2010) The logic of qualitative survey research and its position in the field of social research methods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 11. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1450/2946

- Schreier, M., Schmitz-Justen, F., Diederich, A., Lietz, P., Winkelhage, J. and Heil, S. (2008) Sampling in qualitativen Untersuchungen: Entwicklung eines Stichprobenplanes zur Erfassung von Präferenzen unterschiedlicher Stakeholdergruppen zu Fragen der Priorisierung medizinischer Leistungen. FOR655, 12. http://www.priorisierung-in-der-medizin.de/documents/FOR655_Nr12_Schreier_et_al.pdf

- Patton, M.Q. (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd Edition, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- UNESCO (2006) International standard classification of education—ISCED 1997. http://www.uis.unesco.org/Library/Documents/isced97-en.pdf

- Frey, J. (2005) Terri Schiavo’s unstudied life. Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A64459-2005Mar24.html

- Bhandari, M. and Giannoudis, P.V. (2006) Evidencebased medicine: What it is and what it is not. Injury, International Journal of the Care of the Injured, 37, 302- 306. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2006.01.034

- Hsieh, H.F. and Shannon, S.E. (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Skirbekk, H. and Nortvedt, P. (2011) Making a difference: A qualitative study on care and priority setting in health care. Health Care Analysis, 19, 77-88. doi:10.1007/s10728-010-0160-x

- Charles, C., Gafni, A. and Whelan, T. (1997) Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and Medicine, 44, 681-692. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3

- Hurst, S.A., Forde, R., Reiter-Theil, S., Slowther, A.M., Perrier, A., Pegoraro, R. and Danis, M. (2007) Physicians’ views on resource availability and equity in four European health care systems. BMC Health Service Research, 7, 137-148. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-137

- Stronks, K., Strijbis, A.-M., Wendte, J.F. and GunningSchepers, L.J. (1997) Who should decide? Qualitative analysis of panel data from public, patients, healthcare professionals, and insurers on priorities in health care. British Medical Journal, 315, 92-96. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7100.92

NOTES

1The real QALY takes into consideration not only life prolongation but also quality of life; the NICE limit is £30.000 not 30.000 Euro and it is not as clear-cut as it is implied here (www.nice.org.uk).

2All quotations were translated into English by the authors.