Materials Sciences and Applications

Vol.4 No.12(2013), Article ID:41132,8 pages DOI:10.4236/msa.2013.412103

Schottkey Barrier Measurement of Nanocrystalline Lu3N@C80/Au Contact

![]()

1Department of Applied Science for Integrated System Engineering, Kyushu Institute of Technology, Fukuoka, Japan; 2Research Institute, Kyushu Kyoritsu University, Fukuoka, Japan; 3Department of Electrical and electronic Engineering, Kitakyushu National College of Technology, Fukuoka, Japan.

Email: *sun@ele.kyutech.ac.jp

Copyright © 2013 Yong Sun et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received October 21, 2013; revised November 28, 2013; accepted December 9, 2013

Keywords: Lu3N@C80; Nanocrystalline; Schottky Barrier; Mobility

ABSTRACT

Electrical and structural properties of nanocrystalline solids of C80 fullerene encapsulated with a Lu3N cluster, Lu3N@C80, have been studied by measuring x-ray photoemission spectra, x-ray diffraction, and current-voltage characteristics of the Lu3N@C80/Au Schottky contact in the temperature range of 300 - 500 K. The nanocrystalline solid sample of Lu3N@C80 fullerene consists of grains characterized with an fcc structure and those grains become larger in size after pressing the powder sample at 1.25 GPa. The current-voltage characteristics measured at various temperatures showed that there are no significant dependences on both the Schottky barrier and the carrier mobility on electric field. The Schottky barrier of the Lu3N@C80/Au contact is determined to be 0.71 ± 0.04 eV.

1. Introduction

Higher fullerenes of C80 are promising agent for organic photovoltaic devices particularly when they encapsulate a M3N cluster (M: Sc, Lu, Er, Dy, Y, Ho, La, Tm, Gd, etc.) inside the C80 cage. The recent isolation technique has succeeded in isolating those M3N endohedral C80 fullerenes, M3N@C80, with a production yield more than ten times higher than other endohedral metallofullerenes [1-4]. Electron transfer from a M3N cluster to the C80 cage as well as the specific charge states of both the cluster and cage is of special interest in photovoltaic solar cells. Bare C80 fullerenes that satisfy the isolated pentagon rule (IPR) [5] have seven isomers [6] with symmetries of Ih, D5d, D5h, D3, D2, C2v and C2v, among which only the D2 and D5d isomers are able to be isolated because of their structural stability. It is known that excessive electrons can stabilize the molecular structure of the C80 cage, so the M3N@C80 molecules with Ih and D5h symmetries can also be obtained [7]. Also, the molecules with the excessive electrons from the endohedral cluster can interact with metal electrodes so that contact resistance at the metal/M3N@C80 interface is reduced [8]. Furthermore, it is reported that the endohedral M3N cluster influences the carrier transport since the current through the Al/M3N@C80/Al system is obtained to be two times larger than that for the Al/C80/Al system [8].

With all the expectations for the promising abilities of M3N@C80 fullerenes for electronic, magnetic and optical devices, their solid state properties have not been well understood, yet. So far, all the theoretical and experimental studies have focused mainly on the chemical and physical properties of an isolated single M3N@C80 molecule, treating structure of the isomers [6,9], HOMOLUMO energy gap [1,6], bond energy [6], electronic structure of neutral as well as ionized molecules [10], molecular dynamics [11,12], superatom [13], size effects of the endohedral clusters[14], magnetic moment [15,16], and optical and electrochemical properties [11,17].

In this study, we have prepared nanocrystalline Lu3N @C80 solids, and revealed their properties about crystallographic structure, oxygen-induced chemical shifts of the core levels of constituting atoms, and effect of applied electric field on the Schottky barrier and the carrier mobility. Schottky barrier of the nanocrystalline Lu3N@ C80/Au contact is evaluated from the temperature-dependent current passing through the sample.

2. Experimental

Solid samples were prepared using Lu3N@C80 powder (purity > 97 wt%) purchased from LUNA Innovations. The Lu3N@C80 powder was pressed into a pellet with two gold electrodes at room temperature at a pressure of 1.25 GPa for 50 min. The so formed pellet was 5 mm in diameter and 0.525 mm thick. Prior to the measurements the powder and pellet samples were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JEOL JSM-7000), x-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS; AXIS-NOVA, SHIMATSU/KRATOS) and x-ray diffraction (XRD; JEOL JDX-3500K). In the XPS analysis the beam diameter of Al Ka line was 55 μm, and the binding energy resolution was 0.15 eV.

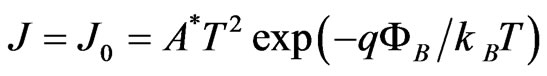

In the electrical measurements, the current passing through the pellet sample were measured using a digital electrometer (ADVANTEST R8252) with a current resolution of 1 f A at various d.c. bias voltages,  , changing from 10 to 200 V. The Au/Lu3N@C80/Au structure consists of two Schottky contacts, connected backto-back. When a d.c. bias is applied, one of the Schottky diodes is forward and the other is reverse biased. At sufficiently high biases, the Au/Lu3N@C80/Au structure can be considered as a reverse-biased diode. Its currentvoltage characteristics can be written as

, changing from 10 to 200 V. The Au/Lu3N@C80/Au structure consists of two Schottky contacts, connected backto-back. When a d.c. bias is applied, one of the Schottky diodes is forward and the other is reverse biased. At sufficiently high biases, the Au/Lu3N@C80/Au structure can be considered as a reverse-biased diode. Its currentvoltage characteristics can be written as  where

where  is the reverse saturation-current density,

is the reverse saturation-current density,  the effective Richardson constant,

the effective Richardson constant,  the Schottky barrier and

the Schottky barrier and  the Boltzmann constant. Hence, from measurements of the temperature dependent current passing through the sample,

the Boltzmann constant. Hence, from measurements of the temperature dependent current passing through the sample,  where A is the area of the electrodes on the sample, the Schottky barrier was obtained.

where A is the area of the electrodes on the sample, the Schottky barrier was obtained.

The pellet sample was set in a vacuum chamber of a cryostat during the electrical measurements. The base pressure of the vacuum chamber was less than 10−5 Pa. The current measurements were carried out in the course of heating up or cooling down process between the temperatures from 300 K to 500 K. The rate of heating or cooling was 0.14 Kmin−1 with a stepwise increment of 1.0 K.

3. Results

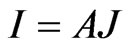

The SEM image of the surface of a Lu3N@C80 pellet sample is shown in Figure 1. The inset shows the structure formula of the Lu3N@C80 molecule. Figure 2 shows three x-ray photoemission spectra of the pellet sample at room temperature. They were obtained from the surface of the Lu3N@C80 sample before and after Ar+ ion sputtering for 10 and 30 s, respectively. Six peaks at biding energies of 12, 205, 287, 535 and 990 eV were observed in the spectra. The 12 eV peak is attributed to a photoemission from valence electrons of Lu atoms. The double peaks at 200 and 210 eV are the photoemissions from Lu

Figure 1. SEM image of the surface of a Lu3N@C80 pellet sample. The inset shows the structure formula of the Lu3N @C80 molecule.

Figure 2. X-ray photoemission spectra of the nanocrystalline Lu3N@C80 sample prepared at a pressure of 1.25 GPa. The spectra are detected on the surface of the sample before and after Ar+ ion sputtering for 10 and 30 s.

4 d 5/2 and 4 d 3/2 core levels. The peak around 287 and 535 eV comes from C 1s and O 1s core level, respectively. The peaks around 990 eV correspond to O KLL and C KVV Auger emissions. Also, the peaks around 240 eV observed after the Ar+ ion sputtering are from Ar 2 p 1/2 and 2 p 3/2 core levers. The measured XPS spectra showed up that the Ar+ ion sputtering causes both decrease in the O-related peaks and increase in the C and Lu-related peaks. This result indicates that the oxygen atoms adsorb only on the sample surface. From the spectrum after the 30 s Ar+ ion sputtering, atomic ratio of Lu/C is evaluated to be 3.24 at%, close to the stoichiometric ratio of 3.61 at% for Lu3N@C80. One should note that the photoemission from the N 1s level cannot be detected due to its smaller relative sensitivity factor (RSF) of 0.505 compared to the Lu 4 d RSF of 2.645. Although the RSF of C 1s is also small, 0.318, the XPS intensity by the C atom is somewhat strong because of the abundant concentration of C atoms in the Lu3N@C80 solid.

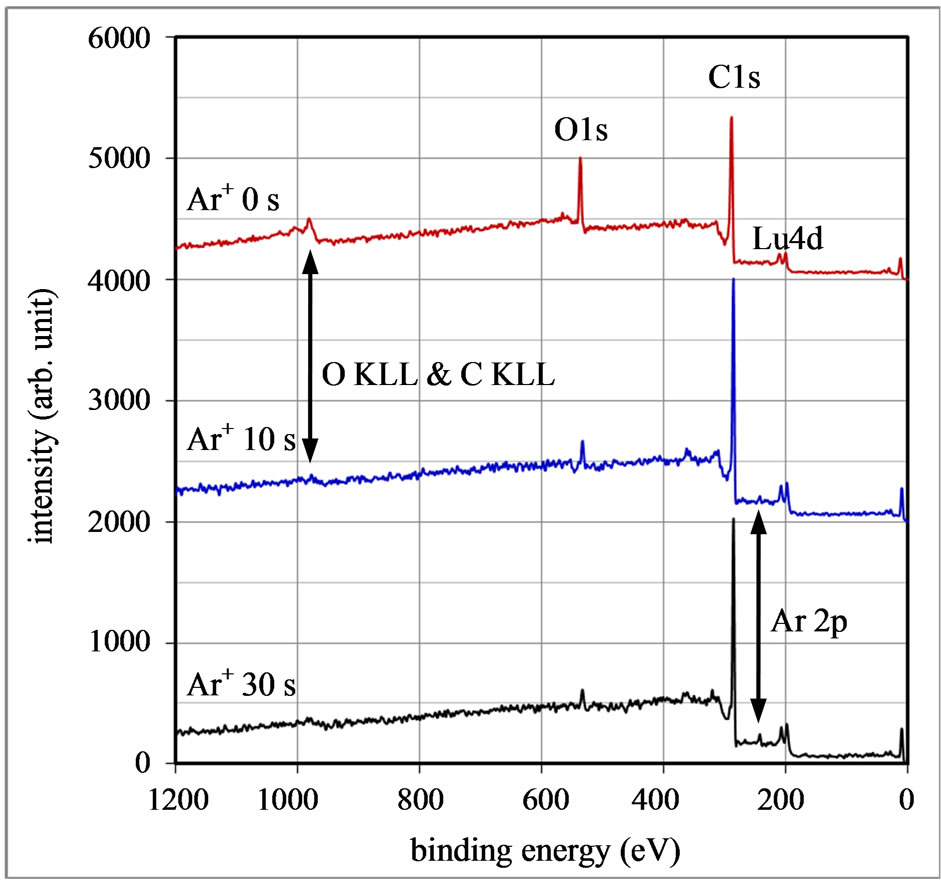

The photoemission spectra from the Lu 4 d 5/2 and 4 d 3/2 and C 1s core levels were enlarged in the energy scaling and they were respectively plotted in Figures 3(a) and (b). The peaks before the Ar+ ion sputtering appears at binding energies of 211 eV for Lu 4 d 3/2, 201 eV for Lu 4 d 5/2 and 289 eV for C 1s core level. On the other hand, the corresponding peaks measured after the sputtering shift to binding energies of 208 eV for Lu 4 d 3/2,

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 3. X-ray photoemission spectra of the nanocrystalline Lu3N@C80 sample before and after Ar+ ion sputtering for 10 and 30 s, (a) the spectra of Lu 4 d 3/2 and 4 d 5/2 core levels and (b) the spectra of C 1s core level.

198 eV for Lu 4 d 5/2 and 287 eV for C 1s core level. Namely, the binding energies of the core levels shift to the low-energy side after eliminating oxygen adatoms by the Ar+ ion sputtering. The XPS peak shift is 3.0 eV for the Lu 4 d 3/2, 3.0 eV for the Lu 4 d 5/2, and 2.0 eV for the C 1s, respectively. The peak of the Lu valence electrons at 12 eV shifts by 2.0 eV towards the low energy side.

The observed chemical shifts to the lower energy side after the oxygen removal suggest that the oxygen adatoms accept electrons from the valence orbitals of both the C80 cage and the endohedral Lu3N cluster.

Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of the Lu3N@C80 powder material as-received and the pellet sample prepared by pressing under the pressure of 1.25 GPa. Several diffraction peaks can be recognized for the two patterns, a strong peak at  degree and three broad peaks centered at

degree and three broad peaks centered at , 34.10 and 50.05 degree. The enlarged XRD pattern of the

, 34.10 and 50.05 degree. The enlarged XRD pattern of the  peaks is shown in the inset to Figure 4. As seen in the inset figure, three new peaks around the

peaks is shown in the inset to Figure 4. As seen in the inset figure, three new peaks around the  degree appear for the pellet sample after the 1.25 GPa pressing. The

degree appear for the pellet sample after the 1.25 GPa pressing. The  peak is ascribed to the diffraction from (111) planes of a fcc grain structure with a lattice constant of 1.61 nm. The grain size of the as-received powder and the pressed pellet sample can be estimated to be 60 and 240 nm from the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the (111) peaks. The XRD result suggests that the 1.25 GPa pressing causes not only the regrowth of the fcc grains involved in the powder material with a lattice constant of 1.61 nm but also growth of the new fcc grains characterized with different lattice constants of 1.82 and 1.50 nm.

peak is ascribed to the diffraction from (111) planes of a fcc grain structure with a lattice constant of 1.61 nm. The grain size of the as-received powder and the pressed pellet sample can be estimated to be 60 and 240 nm from the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the (111) peaks. The XRD result suggests that the 1.25 GPa pressing causes not only the regrowth of the fcc grains involved in the powder material with a lattice constant of 1.61 nm but also growth of the new fcc grains characterized with different lattice constants of 1.82 and 1.50 nm.

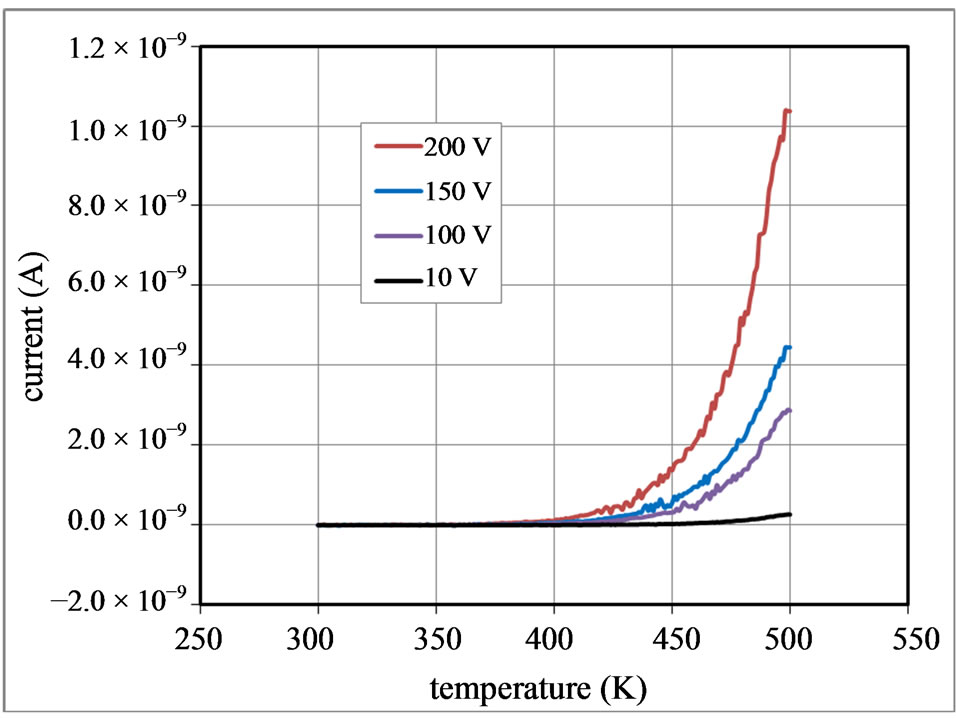

The current I passing through the pellet sample at  =10, 100, 150 and 200 V were measured as a function of temperature T, and the obtained results were plotted in Figures 5(a) and (b) during heating up and cooling down

=10, 100, 150 and 200 V were measured as a function of temperature T, and the obtained results were plotted in Figures 5(a) and (b) during heating up and cooling down

Figure 4. X-ray diffraction patterns of the as-received Lu3N@C80 powder and its pellet sample prepared at a pressure of 1.25 GPa. The inset shows the enlarged patterns of the (111) diffraction peaks.

process, respectively. One may notice that I exponentially increases with T above 400 K. No hysteresis was recognized in the I vs T curves obtained during the heating up and cooling down processes.

Arrhenius plots of  at various

at various  were shown in Figures 6(a) and (b) for the measurements during heating up and cooling down process, respectively. The good linear relationship found in the Arrhenius plots in Figure 6 suggests that carriers are generated by thermal activation over the Schottky barrier

were shown in Figures 6(a) and (b) for the measurements during heating up and cooling down process, respectively. The good linear relationship found in the Arrhenius plots in Figure 6 suggests that carriers are generated by thermal activation over the Schottky barrier  . The values of the Schottky barrier were determined as a function of the applied electric field E which were evaluated by a relation

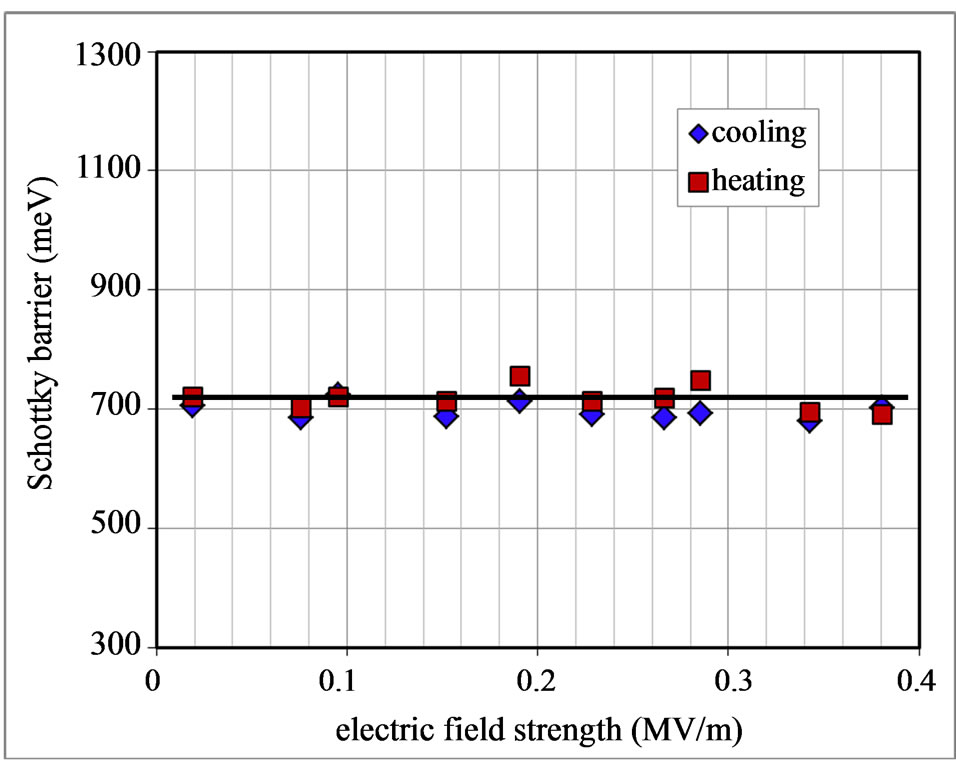

. The values of the Schottky barrier were determined as a function of the applied electric field E which were evaluated by a relation  for the sample thickness d. Results during heating up and cooling down were plotted in Figure 7. It is clear that the Schottky barrier is constant, not affected by E as well as either by the course of heating up or cooling down process. From Figure 7 it is determined that

for the sample thickness d. Results during heating up and cooling down were plotted in Figure 7. It is clear that the Schottky barrier is constant, not affected by E as well as either by the course of heating up or cooling down process. From Figure 7 it is determined that  = 0.71 ± 0.04 eV.

= 0.71 ± 0.04 eV.

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 5. Temperature-dependent current passing through the nanocrystalline Lu3N@C80 sample at various d.c. bias voltages, (a) during heating up and (b) during cooling down process.

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 6. Arrhenius plots of J0T−1 at various d.c. bias voltages, (a) during heating up and (b) during cooling down process.

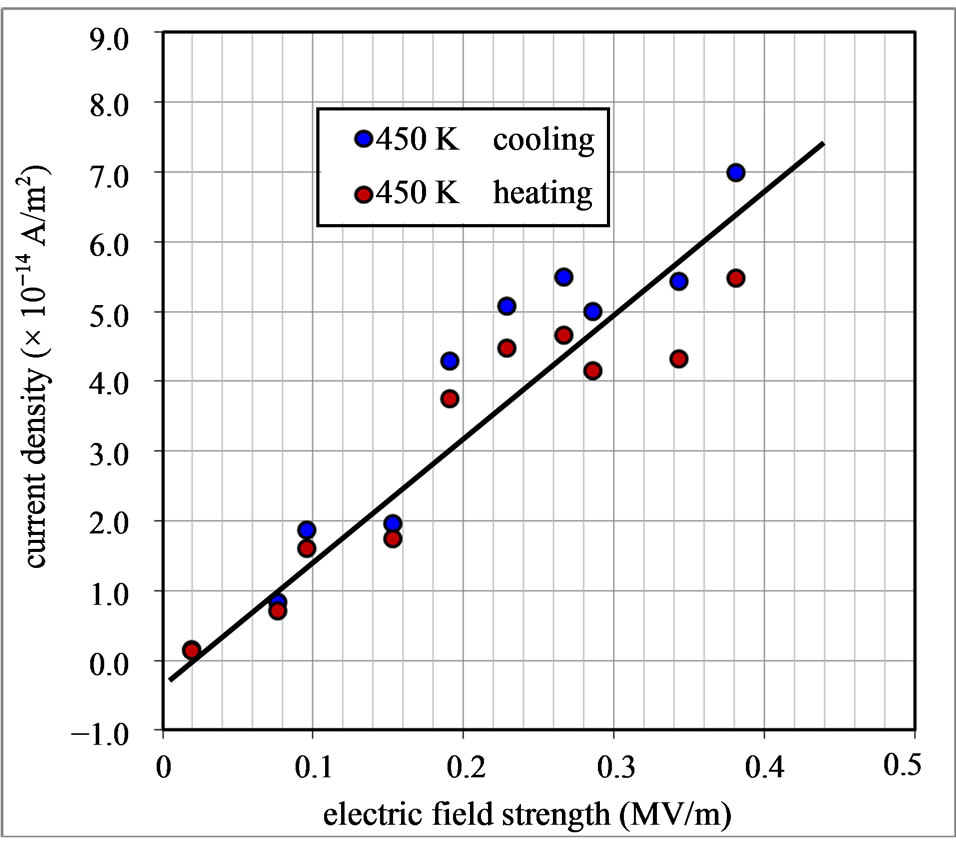

Density  of the current passing through the Lu3N @C80/Au structure at temperature of 450 K was plotted in Figure 8 as a function of E. The reverse current

of the current passing through the Lu3N @C80/Au structure at temperature of 450 K was plotted in Figure 8 as a function of E. The reverse current  does not saturate and increases slowly with increasing E from 0 to 0.4 MVm−1. As shown in Figure 7 there is not significant electric field dependence on the Schottky barrier. Therefore, the increase of

does not saturate and increases slowly with increasing E from 0 to 0.4 MVm−1. As shown in Figure 7 there is not significant electric field dependence on the Schottky barrier. Therefore, the increase of  with increasing electric field strength may be due to the tunneling effect of the carrier through the Schottky barrier and the carrier recombination in depletion layer. The bulk resistance decrease of the Lu3N@C80 solid phase can also result in the increase of

with increasing electric field strength may be due to the tunneling effect of the carrier through the Schottky barrier and the carrier recombination in depletion layer. The bulk resistance decrease of the Lu3N@C80 solid phase can also result in the increase of .

.

4. Discussion

4.1. Schottky Barrier and Energy Band Gap

Compared to the HOMO-LUMO energy gaps of C60 and

Figure 7. Schottky barrier of the Lu3N@C80/Au contact as a function of the electric field strength during heating up and cooling down process.

Figure 8. The density of the current passing through the Lu3N@C80/Au contact at temperature of 450 K as a function of the electric field strength during heating up and cooling down process.

C70 fullerenes, that of the C80 fullerene is small, 0.55 eV for D2, 0,12 eV for Ih, 0.25 eV for D5d, 0.12 eV for D5h, 0.11 eV for C2v’, 0.20 eV for D3, and 0.11 eV for C2v isomer. Except for the D2 and D5d isomers, the bare C80 isomers are unstable and still not be synthesized [6]. However, it is known that the encapsulation of the M3N cluster makes them stable, and then the M3N@C80 molecule with Ih and D5h symmetries can be stably extracted [7]. Electron transfer from the M3N cluster to the C80 cage plays the most crucial role to the stability of the fullerenes with highly symmetrical geometries. Photoemission and x-ray absorption studies have indeed revealed that the C80 cages with Ih and D5h symmetries are stabilized by the excessive electrons transferred from the M3N cluster [1].

HOMO-LUMO energy gaps of anions and cations of C80 fullerene with the Ih symmetry have been calculated using ab initio molecular-orbital method [6]. It is 0.12 eV for neutral isomer, 0.38 eV for +2 cation, 0 eV for −2 anion, and 2.19 eV for −6 anion of the C80 isomer. On the other hand, theoretical calculations for the [Lu3N]+6@ [C80]−6 molecule showed that its HOMO-LUMO energy gap is 1.54 - 2.55 eV [4,18]. Previous experimental studies also showed that the HOMO-LUMO gap of a [Lu3N]+6@[C80]−6 molecule is 1.31 - 1.65 eV [19,20] for optical absorption and 2.04 eV [4] for electrochemical measurement, respectively. In general, Schottky barrier of the semiconductor/metal is smaller than energy band gap of the semiconductor. In this study, the obtained Schottky barrier of the nanocrystalline [Lu3N]+6@[C80]−6 /Au contact is 0.71 ± 0.04 eV.

4.2. Electric Field Dependence of the Carrier Mobility

In general, the carrier mobility of fullerene crystals is very low due to impurity and poor crystallinity. For example, the electron drift mobility of C60 crystal is in the 1 cm2V−1s−1 range and the hole mobility is smaller than that of electron in three orders of magnitude [21-23]. Sato et al. [24] have reported a study for measuring mobility of the Sc3N@C80 film with large grain size of several micrometers. The electron mobility of Sc3N@C80 film under room temperature and atmospheric pressure is 5.7 × 10−3 cm2V−1s−1. The low mobility values indicate that the carrier propagation in the fullerene crystals is by hopping. The mobility in the order of 10−3 cm2V−1s−1 gives a mean free path smaller than the molecular size, indicating that the band conduction model is not correct. A more likely mechanism of carrier transport in the fullerene solid would be hopping between grains or neighboring molecules. It is also reported that the carrier mobility of C60 crystal at temperatures above 300 K is independent of temperature [22,25].

We have discussed the free time dependence of the mobility above. From the electron mobility of  where

where  is the mean free time and

is the mean free time and  the electron effective mass, the mobility is also dependent of the effective mass

the electron effective mass, the mobility is also dependent of the effective mass . If we assume that the mean free time

. If we assume that the mean free time  of electron in the Lu3N@C80 solid phase is constant during measurements of the electric field dependence, the

of electron in the Lu3N@C80 solid phase is constant during measurements of the electric field dependence, the  depends only on the effective Richardson constant,

depends only on the effective Richardson constant,  where

where  is the Planck’s constant. Therefore, the increase in the reverse saturation-current density

is the Planck’s constant. Therefore, the increase in the reverse saturation-current density  as shown in Figure 8 may be related to the increase in the electron effective mass

as shown in Figure 8 may be related to the increase in the electron effective mass  with increasing electric field.

with increasing electric field.

4.3. Effects of the Adsorbed Oxygen Atoms

The XPS spectra of the Lu3N@C80 solid convey information of the thin surface layer within the depth of only 5 nm. Therefore, effects of the adsorbed oxygen atoms on the binding energies of C 1s and Lu 4 d are sensitively detected as seen in Figure 3. Due to the adsorption of oxygen atoms, the binding energy increases by 2 eV for the C 1s level and by 3 eV for the Lu 4 d 5/2 and d 3/2 levels, respectively. Compared to the Schottky barrier of the Lu3N@C80 solid, the shifts of the C and Lu-related levels are large. However, in this study the effect of impurity oxygen atoms on the measurement of the Schottky barrier of the Lu3N@C80 solid phase can be ignored because of a small concentration or a just physical adsorption of oxygen atoms.

4.4. Interaction between the Applied Electric Field and the Dipoles in Lu3N@C80 Molecule

The M3N cluster can adopt ten equivalent orientations in the C80 cage by aligning its C3 axis to ten different C3 axes of the C80 cage. For each orientation, the cluster can occupy four equivalent positions with different azimuths corresponding to the rotation about its C3 axis. Popov et al. [26] reported a calculation of molecular orientational dynamics of the Lu3N cluster in the C80 cage. A thermal activation behavior of the cluster rotation appears, strongly depending on the cluster orientation with respect to the C80 cage. The barriers to the cluster rotation with respect to the C3 axes of the C80 cage are below 155 meV, and have a minimum closing to zero at room temperature. The barriers to the cluster rotation inside the C80 cage are also found to somewhat increase in the charged states [26]. It is well known that there are dipoles in the M3N cluster due to the electron transfer from metal atoms to nitrogen atoms [27]. However, no coupling between the applied electric field and the dipoles in the M3N cluster is observed in this study. This is due to a high symmetry of three dipoles in the Lu3N molecule as well as a screening effect of both the high-speed rotating C80 cage and the excessive electrons on it.

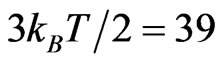

High-speed rotation of the Lu3N@C80 molecule at room temperature have a high relaxation rate due to the enlarged cage size, the excessive electrons as well as the additional dipole-dipole interaction between the endohedral cluster and the C80 cage, compared with the empty fullerenes such as C60 and C70 [12,28]. Furthermore, polarizations of the M3N@C80 molecule have been reported and its polarizability increases with increasing molecular diameter [27]. In order to estimate the influence of the M3N@C80 molecular polarization, we can calculate the potential energy of a dipole with elementary charge on the C80 cage by using  where q is the elementary charge, E the strength of applied electric field and

where q is the elementary charge, E the strength of applied electric field and  the diameter of the C80 cage. We have the potential energy of the Lu3N@C80 molecule having the dipole with elementary charge,

the diameter of the C80 cage. We have the potential energy of the Lu3N@C80 molecule having the dipole with elementary charge,  meV where diameter of the C80 cage is 1 nm and the maximum electric field strength used in this study is 0.4 MVm−1. It is clear that the potential energy is much smaller than the mean kinetic energy of a molecule,

meV where diameter of the C80 cage is 1 nm and the maximum electric field strength used in this study is 0.4 MVm−1. It is clear that the potential energy is much smaller than the mean kinetic energy of a molecule,  meV at room temperature. Therefore, even there is a dipole in the Lu3N@C80 molecule, its polarization effect cannot be observed due to strong thermal rotation and diffusion motions of the molecule.

meV at room temperature. Therefore, even there is a dipole in the Lu3N@C80 molecule, its polarization effect cannot be observed due to strong thermal rotation and diffusion motions of the molecule.

Similar to the results of polarization effects of the endohedral Lu3N cluster, we can also conclude that polarization effects of the Lu3N@C80 molecule can be ignored under the condition of the electric field strength used in this study, thus the capacitance or the Schottky barrier of the Lu3N@C80/Au contact is independent of applied electric field.

5. Conclusion

We have studied the structural properties of the nanocrystalline Lu3N@C80 fullerene solid with fcc structure by x-ray photoemission spectroscopy and x-ray diffraction measurement. The current-voltage characteristics of the Lu3N@C80/Au Schottky contact were measured at various electric fields and temperatures. The Schottky barrier of the Lu3N@C80/Au contact is estimated to be 0.71 ± 0.04 eV and the effect from the applied electric field can be ignored. The interaction between the applied electric field and the dipoles in the endohedral Lu3N cluster and the C80 cage cannot be observed.

6. Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Akira Namiki for fruitful discussions and valuable comments. This work was partially supported by project No. 15-B01, Program of Research for the Promotion of Technological Seeds, Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST). It was also partially supported by Grant-in-Aid for Exploratory Research No: 23651115, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

REFERENCES

- S. Stevenson, G. Rice, T. Glass, K. Harich, F. Cromer, M. Jordan, J. Craft, E. Hadju, R. Bible, M. Olmstead, K. Maitra, A. Fisher, A. Balch and H. Dorn, “Small-Bandgap Endohedral Metallofullerenes in High Yield and Purity,” Nature (London), Vol. 401, No. 6748, 1999, pp. 55-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/43415

- L. Dunsch, M. Krause, J. Noack and P. Georgi, “Endohedral Nitride Cluster Fullerenes: Formation and Spectroscopic Analysis of L3−xMxN@C2n (0≤x≤3; N=39,40),” Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, Vol. 65, No. 2-3, 2004, pp. 309-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2003.03.002

- S. F. Yang, M. Kalbac, A. Popov and L. Dunsch, “Gadolinium-Based Mixed-Metal Nitride Clusterfullerenes GdxSc3−xN@C80 (x=1, 2),” ChemPhysChem, Vol. 7, No. 9, 2006, pp. 1990-1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cphc.200600323

- T. Cai, L. Xu, M. R. Anderson, Z. Ge, T. Zuo, X. Wang, M. M. Olmstead, A. L. Baich, H. W. Gibson and H. C. Dom, “Structure and Enhanced Reactivity Rates of the D5h Sc3N@C80 and Lu3N@C80 Metallofullerene Isomers: The Importance of the Pyracylene Motif,” Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 128, No. 26, 2006, pp. 8581-8189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja0615573

- H. W. Kroto, “The Stability of the Fullerenes Cn, with n = 24, 28, 32, 36, 50, 60 and 70,” Nature, Vol. 329, No. 6139, 1987, pp. 529-531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/329529a0

- K. Nakao, N. Kurita and M. Fujita, “Ab initio MolecularOrbital Calculation for C70 and Seven Isomers of C80,” Physical Review B, Vol. 49, No. 16, 1994, pp. 11415- 11420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.49.11415

- M. Krause and L. Dunsch, “Isolation and Characterisation of Two Sc3N@C80 Isomers,” ChemPhysChem, Vol. 5, No. 9, 2004, pp. 1445-1449. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cphc.200400085

- B. Larade, J. Talor, Q. R. Zheng, H. Mehrez, P. Pomorski and H. Guo, “Renormalized Molecular Levels in a Sc3N @C80 Molecular Electronic Device,” Physical Review B, Vol. 64, No. 19, 2001, Article ID: 195402.

- T. R. Cummins, M. Burk, M. Schmidt, J. F. Armbruster, D. Fuchs, P. Adelmann, S. Schuppler, R. H. Michel and M. M. Kappes, “Electronic States and Molecular Symmetry of the Higher Fullerene C80,” Chemical Physics Letters, Vol. 261, No. 3, 1996, pp. 228-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(96)00973-6

- A. Muller, S. Schippers, R. A. Phaneuf, M. Habibi, D. Esteves, J. C. Wang, A. L. D. Kilcoyne, A. Aguilar, S. Yang and L. Dunsch, “Photoionization of the Endohedral Fullerene Ions Sc3N@C80+ and Ce@C82+ by Synchrotron Radiation,” Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol. 88, 2007, Article ID: 012038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/88/1/012038

- M. Krause, H. Kuzmany, P. Georgi, L. Dunsch, K. Vietze and G. Seifert, “Structure and Stability of Endohedral Fullerene Sc3N@C80: A Raman, Infrared, and Theoretical Analysis,” Journal of Chemical Physics, Vol. 115, 2001, pp. 6596-6605. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1399298

- S. Klod, L. Zhang and L. Dunsch, “The Role of the Cluster on the Relaxation of Endohedral Fullerene Cage Carbons: A NMR Spin-Lattice Relaxation Study of an Internal Relaxation Reagent,” Journal of Physical Chemistry C, Vol. 114, No. 18, 2010, pp. 8264-8267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp101218p

- T. Huang, J. Zhao, M. Feng, H. Petek, S. Yang and L. Dunsch, “Superatom Orbitals of Sc3N@C80 and Their Tntermolecular Hybridization on Cu(110)-(2×1)-O Surface,” Physical Review B, Vol. 81, No. 8, 2010, Article ID: 085434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.81.085434

- L. Xu, S. F. Li, L. H. Gan, C. Y. Shu and C. R. Wang, “The Structures of Trimetallic Nitride Fullerenes M3N@ C88: Theoretical Evidence of Corporation between Electron Transfer Interaction and Size Effect,” Chemical Physics Letters, Vol. 521, 2012, pp. 81-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2011.11.011

- L. Chen, E. E. Carpenter, C. S. Hellberg, H. C. Dorn, M. Shultz, W. Wernsdorfer and I. Chiorescu, “Spin Transition in Gd3N@C80, Detected by Low-Temperature onchip SQUID Technique,” Journal of Applied Physics, Vol. 109, 2011, Article ID: 07B101.

- M. Wolf, K. H. Muller, D. Eckert, Y. Skourski, P. Georgi, R. Marczak, M. Krause and L. Dunsch, “Magnetic Moments in Ho3N@C80 and Tb3N@C80,” Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, Vol. 290-291, 2005, pp. 290-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2004.11.211

- M. E. Plonska-Brzezinska, A. J. Athans, J. P. Phillips, S. Stevenson and L. Echegoyen, “. A Reinvestigation of the Electrochemical Behavior of Sc3N@C80,” Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, Vol. 614, No. 1-2, 2008, pp. 171-174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2007.11.013

- Y. Zhu, Y, Li and Z. Q. Yang, “First-Principles Investigation on the Electronic Structures of Intercalated Fullerenes M3N@C80 (M=Sc, Y, and lanthanides),” Chemical Physics Letters, Vol. 461, No. 4-6, 2008, pp. 285- 289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2008.07.045

- S. Stevenson, H. M. Lee, M. M. Olmstead, C. Kozikowski, P. Stevenson and A. L. Balch, “Preparation and Crystallographic Characterization of a New Endohedral, Lu3N@C8 5 (o-xylene), and Comparison with Sc3N@C80 5 (o-xylene),” Chemistry—A European Journal, Vol. 8, No. 19, 2002, pp. 4528-4535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1521-3765(20021004)8:19<4528::AID-CHEM4528>3.0.CO;2-8

- E. B. Iezzi, J. C. Duchamp, K. R. Fletcher, T. E. Glass and H. C. Dorn, “Lutetium-Based Trimetallic Nitride Endohedral Metallofullerenes: New Contrast Agents,” Nano Letters, Vol. 2, No. 11, 2002, pp. 1187-1190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/nl025643m

- R. Konenkamp, G. Priebe and B. Pietzak, “Carrier Mobilities and Influence of Oxygen in C60 Films,” Physical Review B, Vol. 60, No. 16, 1999, pp. 11804-11808. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.60.11804

- E. Frankevich, Y. Maruyama and H. Ogata, “Mobility of Charge Carriers in Vapor-Phase Grown C60 Single Crystal,” Chemical Physics Letters, Vol. 214, No. 1, 1993, pp. 39-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(93)85452-T

- G. Priebe, B. Pietzak and R. Konenkamp, “Determination of Transport Parameters in Fullerene Films,” Applied Physics Letters, Vol. 71, 1997, pp. 2160-2162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.119368

- S. Sato, S. Seki, G. Luo, M. Suzuki, J. Lu and S. Nagase, “Tunable Charge-Transport Properties of Ih-C80 Endohedral Metallofullerenes: Investigation of La2@C80, Sc3N @C80, and Sc3C2@C80,” Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 134, No. 28, 2012, pp. 11681-11686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja303660g

- E. Frankevich, Y. Maruyama and H. Ogata, “Mobilities of Charge Carriers in C60 Orthorhombic Single Crystal,” Solid State Communications, Vol. 88, 1993, pp. 177-181.

- A. A. Popov and L. Dunsch, “Hindered Cluster Rotation and 45Sc Hyperfine Splitting Constant in Distonoid Anion Radical Sc3N@C80−, and Spatial Spin-Charge Separation as a General Principle for Anions of Endohedral Fullerenes with Metal-Localized Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbitals,” Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 130, No. 52, 2008, pp. 17726-17742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja804226a

- J. He, K. Wu, R. Sa, Q. Li and Y. Wei, “Dipole Polarizabilities of Trimetallic Nitride Endohedral Fullerenes M3N @C2n (M=Sc and Y; 2n=68 – 98),” Chemical Physics Letters, Vol. 475, No. 1-3, 2009, pp. 73-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2009.05.010

- S. Klod and L. Dunsch, “Influence of the Cage Size on the Dynamic Behavior of Fullerenes: A Study of 13C NMR Spin-Lattice Relaxation,” ACS NANO, Vol. 4, No. 6, 2010, pp. 3236-3240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/nn1002024

NOTES

*Corresponding author.