Modern Economy

Vol.08 No.01(2017), Article ID:73719,30 pages

10.4236/me.2017.81008

Analysis of Foreign Direct Investment, Agricultural Sector and Economic Growth in Tanzania

Manamba Epaphra, Ales H. Mwakalasya

Department of Accounting and Finance, Institute of Accountancy Arusha, Arusha, Tanzania

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: December 18, 2016; Accepted: January 20, 2017; Published: January 23, 2017

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes the effect of foreign direct investment (FDI) on agricultural sector in Tanzania. The paper also examines the declining contribution of agriculture to real GDP growth despite the fact that the sector employs more than 70 percent of the total labour force. Annual time series data spanning from 1990 to 2015 are used to test the significance of the relationship between FDI inflow and agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio on one hand and FDI inflows and economic growth on the other hand. Also, the relationship between agriculture value added and economic growth rate is empirically examined. Variables such as gross fixed capital formation, inflation rate, trade liberalization, real exchange rate and population are considered as control variables. For the purpose of inference, the paper employs classical linear regression model. Ordinary least squares methods are used for estimation. The diagnostic tests including RESET regression errors specification test, Breusch-Godfrey serial correlation LM test, Jacque-Bera-normality test and white heteroskedasticity test reveal that the models have no signs of misspecification and that, the residuals are serially uncorrelated, normally distributed and homoskedastic. Interestingly, empirical results suggest that there is no significant effect of FDI inflows on agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio in Tanzania despite the fact that FDI inflows in economy have been outstanding particularly in past two decades. Unsurprisingly, the results show that FDI inflows-to-GDP ratio and real GDP growth rate are positively correlated. Notwithstanding, agriculture sector, which constitutes the largest proportion of the total labour force, contributes, on average, less than 30 percent, to total GDP. This suggests that the sector is inefficient and therefore, effort towards attracting more FDI aiming at improving productivity in agriculture sector, which in turn may reduce poverty, is much needed.

Keywords:

Foreign Direct Investment, Agricultural Sector, Economic Growth

1. Introduction

FDI has been shown to play an important role in promoting economic growth, raising a country’s technological level, creating new employment opportunities and offering a source of external capital in developing countries (Loungani & Razin [1] ). Apart from that, there is a learning advantage, whereby FDI provides a room for local governments, local businesses and citizens to learn new business practices, management techniques and concepts that help them develop local businesses and industries (Kumar [2] ). In fact, FDI works as a means of integrating developing countries into the global market place and increasing the capital available for investment, thus, leading to increased economic growth needed to reduce poverty and raise living standards (Rutihinda [3] and Dollar & Kraay [4] ). Over the 2000-2010 periods, FDI has contributed in excess of 20 percent to GDP in developing countries such as Brazil, Cambodia, Ghana, Tanzania and Thailand (FAO [5] ). Surprisingly, the agricultural sector that is key to many African countries employment, food security and poverty reduction has long been neglected. The lack of private and public investment has led to lower productivity growth rates and stagnant production in many developing countries (Heumesser & Schmid [6] ).

During the past 20 years, there has been a marked increase in both the flow and stock of FDI in the world economy. For example, FDI flows to developing economies increased by 2 percent to a historically high level in 2014, reaching US $681 billion (UNCTAD [7] ). In Tanzania, with the initiation of economic reforms in 1986, investment interest in the country has grown considerably in mining and quarrying and manufacturing sectors. Under the Tanzania Investment Promotion Policy of 1990, the Investment Promotion Centre was established and by 1997, it had approved about 1025 projects worth US $3.1 billion (URT [8] ). According to the Bank of Tanzania Data, annual FDI inflows in Tanzania increased steadily from US $157.8 million in 1997 to US $202.7 million in 2001, averaging US $182 million a year. Understandably, between 2000 and 20014, Tanzania had one of the strongest growth rates of the non-oil-producing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. During that period, annual real GDP growth was, on average, 6.6 percent, with 7.2 percent in 2014 (WDI [9] ). However, per-capita GDP remains low. Agriculture, which accounts for the largest share of total labour force records low levels of investment expenditure. For example, the annual FDI inflows to agriculture are lower than that of mining and quarrying and manufacturing which account for 3.4 percent and 8.2 percent share in GDP respectively (Tanzania Investment Center [10] ).

Notably, Tanzanian agriculture is dominated by smallholders with low levels of productivity, but also limited education, skills and experience, and insufficient access to credit and input (FAO [5] ). Their low performance, small-scale and weak institutional arrangements therefore, do not make them a viable option for joint ventures with foreign investors (FAO [5] ). As a result, up until 2007, the poverty rate in Tanzania remained stagnant at around 34 percent of the whole population despite a robust growth at an annualized rate of approximately 7 percent. A huge percentage of population living below the standard poverty line is that of small scale farmers leaving in rural areas. Thus, growth in agriculture and its productivity are considered essential in achieving sustainable growth and significant reduction in poverty in low income countries such as Tanzania.

This paper aims at empirically examining the impact of FDI on agricultural value added. This is significant due to the fact that even with huge FDI inflows to the economy there is still lower impact on agriculture performance hence leading to extreme poverty among small holder farmers and all those involved in agricultural activities. The sector constitutes about 70 percent of the workforce in Tanzania. Indeed, the country is largely dependent on agriculture for employment. The agriculture sector grew by 4.2 percent in 2013, compared with 6.2 percent in 2001, despite the provision of subsidized inputs coupled with the ongoing construction and rehabilitation of infrastructure including roads, markets and irrigation schemes. The paper also examines the declining contribution of agriculture sector in real GDP growth even though the economy improves due to factors such as FDI.

2. Agricultural Sector and FDI Inflows

The flow of FDI into agriculture sector in Tanzania is important because growth in agriculture and its productivity are considered essential in achieving sustainable growth and significant reduction in poverty. Agriculture value added over the 1991-2013 period was on average more than 30 percent (Table 1). More than 70 percent of the people employed are engaged in agriculture. Unexpectedly, agriculture relative productivity level is only 0.4 whereas mining & utilities and manufacturing sectors relative productivity levels average at 7.7 and 3.3 respectively (Table 1). In fact, agriculture in Tanzania is smallholder based with almost 60 percent of households having farms of less than 2 hectares, and another 20 percent falling in the 2 - 3 hectares category (Amani & Mkumbo [11] ). The sector has performed less, averaging less than 4 percent during the last two decades, compared to the economy’s overall 6.4 percent annual average growth over the same period, while population growth was estimated at 2.7 percent (WDI [9] ). The rate of growth of agriculture indeed, was well below the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty’s target of 10 percent by 2010. As a result, the agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio has declined from 46.0 percent in 1990 to 31.2 percent in 2015 (WDI [9] ).

Given the large proportion of Tanzanian households that rely on farming for their livelihoods and the high rate of rural poverty, the overwhelmingly majority of poor Tanzanians are primarily dependent on agriculture. Indeed, 18.4 of the rural population live below the food poverty line compared to 12.9 percent in other urban areas (Amani & Mkumbo [11] ). The fact that over 70 of the population in Tanzania lives in rural areas and that agriculture is the mainstay of their living, any strategies to address poverty must involve actions to improve agricultural productivity and farm incomes (Msuya [13] ). More importantly, productivity growth in the agricultural sector is being viewed by both developmental

Table 1. GDP, Employment and Relative Productivity Levels, Tanzania, 1991-2013.

Notes: Derived by calculating labour productivity levels (gross value added at constant prices divided by number of persons employed per sector) and by expressing the result as a ratio of total economy labour productivity. Source: Supporting Economic Transformation (SET) [12] .

and agricultural economists as paramount if agricultural output is to increase at a sufficiently rate to tackle poverty (Rao, et al. [14] ). Productivity apart, agricultural investment at the farm level can increase the availability of food on the market and help keep consumer prices low, making food more accessible to rural and urban consumers (Alston, et al. [15] ).

The World Investment Report [16] shows that in 2014, the top five FDI recipients were Mozambique with US $4.9 billion, Zambia with US $2.5 billion, the United Republic of Tanzania with US $2.1 billion, the Democratic Republic of the Congo with $2.1 billion and Equatorial Guinea with US $1.9 billion. These five countries accounted for 58 percent of total FDI inflows to LDCs reinforced by the export specialization of these countries (World Investment Report [16] ). Remarkably, FDI inward stock in Tanzania in 2014 was as much as US $17 mainly due to gas discoveries and mineral exports. Likewise, improved macroeconomic performance, political stability and market liberalization since the second half of 1990s have led to a surge in investor interest and have encouraged the inflow of foreign capital.

During the 2008-2012 periods, the FDI inflows and stocks have increased steadily (Table 2). The share of FDI stock as a percent of GDP reflects the importance of FDI activity in the country’s productive process and shows the potential impact of FDI stock (Portelli [17] ). Nevertheless, the economy has experienced FDI inflows upsurge in the mining and manufacturing sectors with relatively low inflows in agriculture sector. Despite its importance, FDI flows to agricultural sector have never exceeded 2 percent of total FDI inflows, since the

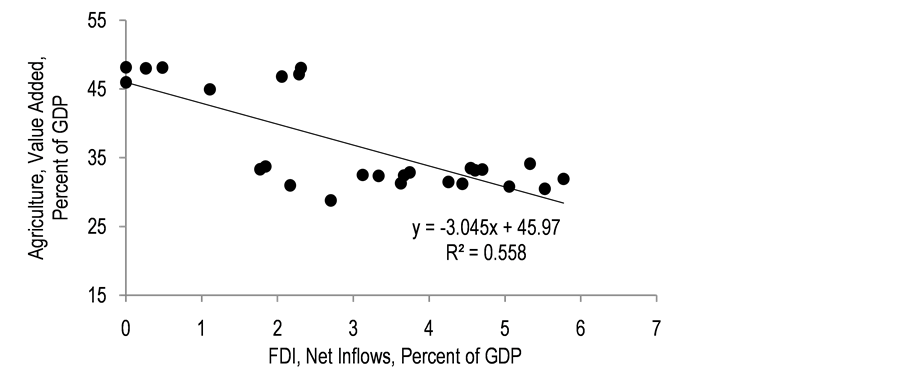

1990s. Over the period between 2008 and 2012, FDI inflows to agricultural sector was on average US $23.1 million, while in mining & quarrying and manufacturing sector were on average USD 652.1 million and USD 286.0 million respectively, during the same period (Table 2). As a result, agriculture remains unimproved. This is reflected in the negative correlation between FDI-to-GDP ratio

Table 2. Flows and Stocks of FDI by Activity (US $ Million), 2008-2012.

Source: Tanzania Investment Report [18] .

and agriculture value added-to-GDP (Figure 1) on one hand, and the inverse association between agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio and real GDP growth on the other hand (Figure 2), whereas the correlation between FDI-to-GDP ratio and real GDP growth is positive (Figure 3). During the last two decades the growth of agriculture sector has been disappointing. The share of agriculture sector in GDP was 49 percent in 1970, 46 percent in 2002 and 26.5 percent in 2007 (Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives [19] ). The fact that the GDP growth has been improving, decline in agriculture implies improvement in the growth in other sectors such as services, manufacturing and mining.

It also suggests that the economy moves away from a subsistence economy. Nonetheless, agriculture remains the mainstay of the economy because of the sizeable share of the labour force engaged in the sector and its important role in the economy, contributing, on average, about 25 percent of total GDP over the past 10 years. Although the mining and manufacturing sectors have registered important real growth rates in recent years, growth is forthcoming from a low

base and both sectors still have relatively small shares of overall GDP. Within the FDI inflows to agriculture, the largest share has higher-stage processing sectors including the food retail sector, while inflows to primary agriculture have remained below 15 percent (FAO [5] )1.

Figure 1. Correlation between FDI and Agriculture, 1990-2015. Source: Authors computations using WDI Data [9] .

Figure 2. Correlation between FDI and Real GDP, 1990-2015. Source: Authors computa- tions using WDI Data [9] .

Figure 3. Correlation between Real GDP and Agriculture, 1990-2015. Source: Authors computations using WDI Data [9] .

Intelligibly, FDI stimulates economic growth in many various ways such as employment creation, technology transfer and capital flow in a country. Tanzania as a host country to many FDIs has also experienced economic growth and development from the liberalization of economy in the mid 1980s. The contribution of FDI to GDP of the country was 0.3 percent in 1992, 4.5 percent in 2000, 6.7 percent in 2008 and 4.6 percent in 2011 (URT [8] ). Peculiarly, the key to achieving broad-based growth lies in the significant improvements in agricultural productivity by raising the levels of investment to agricultural sector which is plagued by infrastructure gaps, poor production technology, inefficiency, high production cost and rapid population growth. Nonetheless, sector accounts for about one fifth of the foreign earnings and supports the livelihoods of more than two thirds of the population (UNESCO [20] ).

Overall, the low average productivity of most small-scale farmers in Tanzania and other Sub-Saharan African countries reveals that small-scale farmers are often unable to overcome the above-mentioned constraints to farming more efficiently, despite the systematic promotion of the smallholder model in the past decades (Collier & Dercon [21] ). Increasing FDI is one important factor contributing to the ongoing transformation of the agricultural sector. FDI in the agricultural sector could contribute to increasing global food supply within a relatively short time and thus contribute to reducing the risks of future food shortages and price hikes (Schüpbach [22] ). FDI may reduce this yield gap by providing financial capital and introducing advanced agricultural technologies as well as the needed skills to employ them efficiently (UNCTAD [23] ). Local producers may gain access to modern technologies and management techniques, either through direct cooperation with foreign companies (e.g. as contract farmers) or indirectly through spillovers effects (UNCTAD [23] ). Also, as Schü- pbach [22] reveals, increased competition may lead local firms to increase their efficiency in order to remain competitive.

Unfavorably, planned expenditure in agricultural sector is biased toward inputs and, recently, rural finance; few resources go to rural infrastructure, value addition, research, and extension. Irrigation expenditure has recently increased but remains insufficient to fill the gap in demand. Rural roads, which are critical for increased agriculture production and productivity, remain significantly underfunded (FAO [24] ). The total actual public spending on agriculture sector has grown at a slower pace. It increased by 30 percent from 2006/07 to 2010/11 reaching TZS 728 billion (FAO [23] ). In relative terms, however, the agricultural budget allocations have declined from almost 13 percent of total government spending in 2006/07 to about 9 percent in 2010/11 (FAO [24] ). Actual spending in relative terms has also decreased significantly in the same period. The highest share of agriculture sector expenditures in the total budget expenditures falls in the 2007/2008 financial year, both in terms of budget allocations and actual spending, reaching 15 and 17 percent respectively. The importance of agriculture in the total government expenditures has been constantly decreasing (FAO [24] ). Moreover, the analysis shows that large share agricultural sector expenditures goes into current spending, not into capital expenditure, which is critical for creating preconditions for long-term growth. Nevertheless, Tanzania’s own capacity to fill financial gap is limited. Given the limitations of alternative sources of investment finance, FDI in developing country agriculture could make a significant contribution to bridging the investment gap.

In 2012 and 2013, the agricultural sector attracted few investors while manufacturing and tourism sectors attracted the largest number of local and foreign investors (Table 3). In 2013 for example, agricultural sector had only 12 approved foreign projects while manufacturing and tourism sectors, respectively, had 75 and 38 approved foreign projects. In 2012 and 2013, agricultural sector attracted 103 total projects worth TZS 1351 million with employment potentials

of 72,574 people while manufacturing sector attracted 550 approved projects worth TZS 5319.80 million with employment potentials of only 50,966 people.

Despite the fact that FDI is seen as potentially providing developmental benefits through for example technology transfer and employment creation, the financial benefits of FDI to the economy of Tanzania is a matter of empirical research. In fact, how far FDIs go towards filling the investment gap is uncertain.

Table 3. Approved Projects, 2012 and 2013.

A: Total number of approved projects; B: New projects C: Old projects (expansion and rehabilitation); D: Local projects; E: Foreign Projects; F: Joint projects; G: Total employment; H: Total investment (TZS Million). Source: Tanzania Investment Centre (TIC) and National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Statistical Abstract [25] .

The low levels of investment in agriculture have led to a decline in agriculture’s share in total economy. Also, the importance of agriculture employment slowly declines reflecting a process of economic diversification from agriculture to new economic sectors and more urbanization. In 2010, however, the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT), an agricultural partnership designed to improve agricultural productivity, food security and livelihoods in Tanzania, was initiated. In March 2016, the World Bank approved a US $ 70m SAGCOT Investment Project to support the agricultural sector of Tanzania and strengthen it by linking smallholder farmers to agribusiness for boosting incomes and job-led growth (World Bank [26] ).

3. Literature Review

Many previous studies on FDIs mainly focus on the impact of FDI on economic growth of a host country and on the determinants of FDI. According to Blom- ström and Kokko ( [27] ) and Borenzstein, et al. ( [28] ), the contributions of FDI to the development of a country are widely recognized as filling the gap between desired investments and domestically mobilized saving, increasing tax revenues, and improving management and technology, as well as labour skills in host countries. In the same line, Adewumi [29] states that in most African countries, inadequate resource to finance long-term investment is a major problem and this lack of investible funds is a big setback to economic growth and thus making it increasingly difficult to achieve the millennium development goals. In point of fact, FDI is seen as a major source of getting the required funds for investments and hence, most African countries offer incentives to encourage it. According to neoclassical theory, FDI influences income growth by increasing the amount of capital per person. It spurs long-run growth through such variables as research and development (R & D) and human capital.

The major determinants of FDI include domestic market size and its growth, domestic business environment, technological capability, trade policy, investment policy and commitment to international rules and agreements (Msuya [13] ). Also, factors such as rate of return, quality of infrastructure, human capital, and political stability may determine FDI in a host country (Msuya [13] ). However, the impact of FDI on economic growth is not automatic. It has been shown that for FDI to contribute to economic growth, the host country must have achieved a minimum threshold level of development in education, technology, infrastructure, financial markets and health (Borenzstein, et al. [28] ). Indeed, FDI contributes to economic growth only when the host country has reached a developmental level capable of absorbing the advanced technology that it brings. According to Klein ( [30] ), the pre-conditions for successful FDI and in order to achieve these positive outcomes for economic growth and poverty reduction, the environment in which foreign investors operate needs to be supportive. This also implies that for successful FDI, there must be an existence of an equal and competitive playing field without special protection for foreign or domestic investors.

Empirical studies suggest that FDI is very important because it provides a source of capital and complements domestic private investment. Many studies such as Blomström and Kokko [27] , Chen & Démurger [31] and FAO [32] conclude that FDI contributes to total factor productivity and income growth in host economies, over and above what domestic investment would trigger. Previous studies find, further, that policies that promote indigenous technological capability, such as education, technical training, and R & D, increase the aggregate rate of technology transfer from FDI and that export promoting trade regimes are also important prerequisites for positive FDI impact (Msuya [13] ).

Studies focusing on the impact of FDI on agriculture have shown that FDI can make a contribution to bridging the investment gap in developing countries’ agriculture. Most of these studies show that there is a positive impact of FDI to the development of agricultural productivity in a host or recipient country. For example Oleyede [33] finds that there exist a positive relationship between FDI and agricultural sector productivity both in the short run and long run. According to Oleyede [33] , FDI stimulates domestic income diversification which in turn boosts agricultural sector. However, political instability would adversely affect agricultural investments in the long run. Similarly, FAO ( [34] ) states that while FDI cannot be expected to become the main source of capital, it can potentially generate various types of benefits for the agricultural sector of the host country such as employment creation, technology transfer and better access to capital and markets. FDI in Agriculture can enhance the efficiency of a nation’s agricultural production by developing investment in heavy areas such as irrigation and infrastructure (FAO [34] ). However, the effectiveness of agricultural FDI in developing countries depends on factors such as agricultural technology, comparative advantage, technical and socio-economic feasibility of proposed FDI arrangements in a transparent and robust manner, institutional frameworks for land governance and small holder competiveness and market access (Oloyede [33] ).

According to Rakotoarisoa [35] , FDI in agriculture can affect different components of the production and marketing chain, from direct production of food and cash crops to entry of farm input providers and food distributors. Other studies show that FDI can help raise agricultural land and labour productivity through farmer training and education, better access to farm inputs, adoption of better farming techniques and improved agricultural technologies that raise crop yields (Almfraji & Almsafir [36] and Görgen, et al. [37] ). Specific FDI on irrigation infrastructure could help improve marginal arable land which in turn leads to its efficient use (Yiyong, et al. [38] ). Also, FDI influences the agricultural exports and enhance the farmer’s access to domestic and international markets through improved storage, transport and communication infrastructure (Yiy- ong, et al. [38] ). Furthermore, the host country of FDI can be expected to benefit more as a result of the spillovers of technology and knowledge from the foreign investing countries. However, the impact of FDI on different on agriculture sector is not straight forward, and in fact it is a matter of empirical research. According to Findlay [39] , Wang & Bloomstrom [40] , UNCTAD [41] and Alfaro [42] transfers of technology and management know-how, introduction of new processes, and employee training associated with FDI tend to relate to the manufacturing sector rather than the agriculture sector. In particular, Alfaro [42] suggests that FDI in the primary sector tends to have a negative effect.

The sectoral distribution of FDI in the economy of Tanzania may be similar to many other developing countries where FDI inflows to agriculture sector is low and hence its contribution to agricultural growth and employment may be relatively less than manufacturing and services sectors although it seems to have a positive effect on the economy in general. Despite the fact that agriculture has immense investment potential, employing more than 70 percent of the total labour force, contributing about 30 percent of GDP, directly producing about 40 percent of total exports, and a key sector in the fight against poverty, it attracts very small share of FDI to Tanzania. Under these circumstances Adewumi [29] shows that it is possible that FDI contributes to the GDP and yet no increase in the welfare of the people in the host country. This could be because investments in agriculture take a considerable time before yielding profits. Mineral sector attracts relatively high FDI because of its immediate profits. Foreign investors refrain from investing in agriculture sector in developing countries due to many factors. Khadaroo [43] argues that companies intending to invest in developing countries and take advantage of lower labour costs, have to deal with higher transport costs and disrupted service due to inadequate transportation means. These are factors that contribute to low FDI inflow to agriculture and hence its small contribution to economic growth and poverty reduction. Although this may be true, FDI in the agricultural sector can improve the welfare in the host country than FDI in mineral sector.

TIR [44] suggests that since agriculture has huge potentials of attracting substantial FDI, governments should endeavour to rigorously promote the activity, undertake land mapping and re-categorization, and enhance rural electrification and infrastructure upgrading.

In summary, it is noteworthy that the empirical literature on the linkage between FDI, agricultural sector and overall economy does not provide a consensus. Some studies document positive effect of FDI on productivity and growth of agricultural sector and overall real GDP while others either report negative relationship or report weak relationship. Besides, the country specific characteristics with respect to the economic, technological, infrastructural and institutional developments indeed matter a lot to gauze empirical relationship (Adhikary [45] ). The present paper thus is of very significant and therefore, it extends a country specific analysis to add knowledge in the empirical literature. To the best of our knowledge, very little research has been conducted on the impact of FDI on agriculture value added on one hand, and the relationship between agriculture value added and economic growth in Tanzania. As stated earlier, most of the previous research has been on the determinants of FDI. Notwithstanding that agriculture is the mainstay of many Tanzanians, and that the share of FDI in agriculture is very small, this paper is significant.

4. Methodology

4.1. Model Specification

A framework of analysis to determine the effects of FDI on agriculture on one hand, and the relationship between FDI and economic growth on the other hand, is formulated by considering all those factors that can potentially play a meaningful role in the determination of agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio and real GDP growth rate. Based on theory and empirical studies discussed under this section, FDI-to-GDP ratio apart, agriculture performance and economic growth are basically determined by factors such as gross fixed capital formation, trade liberalization or degree of openness, exchange rate, labour force and inflation rate. Specified model for agriculture performance and the expected signs of the coefficients of regressors is as follows:

(1)

Similarly the impact of agriculture performance in economic growth is expressed as:

(2)

The variables appearing in the equations are defined as follows:

From Equations (1) and (2), log-linear functional forms are adopted to reduce the possibility or severity of heterogeneity and directly obtain agriculture and growth elasticises with respect to regressors. The regression models are thus of the forms.

(3)

where

= parameters to be estimated,

= the period of time, years,

= white noise error term, i.e.

and

(4)

where

= parameters to be estimated,

= the period of time, years,

= white noise error term, i.e.

The data for the variables which are included in the estimation models (agriculture sector valued added, real per capita GDP, FDI, real exchange rate, trade as a percent of GDP, real exchange rate and inflation rate) are obtained from UN Statistics Division [46] , World Bank World Development Indicators [9] , UNC- TAD [7] , World Investment Report [16] , Bank of Tanzania [47] and Tanzania Investment Centre [10] .

As has been noted, the rationale for including the different variables in the models is based on theory and priory information. As shown above, the main augment is that if FDI inflow increases then it will increase the value added of agricultural sector and overall GDP growth through advancement of the technology and improvement of managerial skills. Feldstein [48] argues that FDI allows the transfer of technology especially in the form of new varieties of capital inputs, which cannot be achieved through financial investment or trade in goods and services. Similarly, Akulava [49] points out that FDI provides firms and economies not only with financial resources, but also with modern technologies, advanced production facilities, new markets and new methods of administration. However, the impact of FDI on agricultural sector and overall economy is not straight forward. To repeat, UNCTAD [41] , Alfaro [42] , Findlay [39] and Wang & Bloomstrom [40] show that transfers of technology and management know-how, introduction of new processes, and employee training associated with FDI tend to relate to the manufacturing sector rather than the agriculture sector. For this reason, FDI tends to have a negative effect on the performance of agriculture sector. Similarly, studies show that as the real GDP raises, the share of agricultural expenditure in total expenditure declines (Singariya & Sinha [50] ). This implies that there is negative correlation between per capita GDP and value added share of agriculture sector in GDP. To emphasize, Singariya & Sinha [50] ) find that the sign of the estimated coefficient in respect of the agricultural sectors is negative suggesting that the share of agricultural sector and real GDP growth moves in opposite direction. The most compelling evidence is that the relative decline of agriculture is clear from both cross-sectional and time-series data (see for example, Anderson [51] ).

Other determinants of agricultural sector performance and the overall growth of the economy include the degree of openness and macroeconomic uncertainty proxied by inflation and real exchange rate. By and large, it is widely accepted that among the driving factors of long-run growth, trade plays an important role in shaping economic performance (Krugman [52] ). Trade liberalization may allow domestic firms access to cheaper and better technology and better quality inputs and managerial skills from abroad (Miller & Upadhyay [53] and Baily & Gersbach [54] ). Other things being equal, opening up foreign trade promotes productivity of agriculture (De Silva, et al. [55] and Hassine, et al. [56] ). It promotes productivity by exploiting comparative advantages that can be gained through exposure to foreign competition, enhanced technical development and access to economies of scale (Jayanthakumaran [57] ). Equally, a liberalized trade regime allows low-cost producers to expand their output beyond that demanded in the domestic market (Krugman [52] ). Even though there are empirical evidence on the significant positive effects of the degree of opennes on economic growth (Dollar [58] , Frankel & Romer [59] , Dollar & Kaaray [60] , Bhagwati & Srinivasan [61] , Wacziarg & Welch [62] ), there are some researchers who dispute these findings on methodological ground (see for example Rodrik [63] and Rodriguez & Rodrik [64] ). Having considered openness of the economy, it is also reasonable to look at the real exchange rate. Chiefly, exchange rate of a country plays a key role in international economic transactions. For example, an increase in exchange rate may increase the demand of domestic products and the cost of imported capital and other imported inputs. If a firm is more dependent on imported inputs, there will be more variable costs and less marginal value of capital (Lotfalipour, et al. [65] ).

Undoubtedly, macroeconomic instability tends to adversely affect economic growth. For example, uncertainty related to higher volatility in inflation could discourage firms from investing in projects that have high returns, but also a higher inherent degree of risk. Generally speaking, investment and growth suffer in cases of high inflation. It is important however to note that, evidence on the relationship between inflation and growth is somewhat mixed (Bassanini & Scarpetta [65] ). In particular, the relationship between the two variables is less clear in cases of moderate or low inflation (Edey [67] and Bruno & Easterly [68] ). Also, in a country when there is demand-pull inflation, due to increasing demand for food, producers invest more in the agricultural sector, resulting in an increased production which in turn lead to an increase in the ratio of agriculture to GDP (De Sormeaux & Pemberton [69] ). Other studies, for example, Chaudhry, et al. [70] evidently, suggest that inflation and agriculture sector growth are positively and significantly related. A contrary explanation is that when there is cost-push inflation, mainly because of a decrease in aggregate agricultural supply, which may be caused by an increase in the prices of raw materials, the costs of agricultural production will increase, which in turn lead to a decline in the ratio of agriculture to GDP (De Sormeaux & Pemberton [69] ).

Also, theories and empirical studies show that factors such population growth rate or labour and gross fixed capital formation can affect the performance of a particular sector and the economy in general. Proponents of labour suggest that population growth allows the rural sector to play a role in fostering economic growth (Pemberton [71] ). On this positive side, a large population provides a large domestic market for the economy. Moreover, population growth encourages competition, which induces technological advancements and innovations (Tsen & Furuoka [72] ). Even though there are evidence on the positive relationship among these variables, other studies show that a large population may reduce productivity because of diminishing returns to more intensive use of land and other natural resources (Malthus [73] ). It also tends to depress savings per capita and retards growth of physical capital per worker (Tsen & Furuoka [72] ).

An equally significant variable is gross fixed capital formation. On this variable, studies show that a country that needs to meet her objective of economic development needs an increase in gross fixed capital formation. Capital is required to construct schools, hospitals, roads, railways, research and development and improve standards of living (Jhingan [74] and Ainabor, et al. [75] ). Nonetheless, like the preceding factors, the effect of gross fixed capital formation on growth or productivity is not conclusive and indeed, it is a matter of empirical research. Certainly, there is no shortage of disagreement within this area of study. For example, Kormendi & Meguire [76] , Barro [77] and Levine & Renelt [78] show that the rate of physical capital formation leads to growth whereas Kendrick [79] suggests that the capital formation alone does not lead to economic prosperity, rather the efficiency in allocating capital from less productive to more productive sectors influences growth.

4.2. Estimation Techniques

The ordinary least squares method (OLS) is used for estimation. OLS is simple and widely used in empirical work. If the model’s error term is normally, independently and identically distributed (n.i.i.d.), OLS yields the most efficient unbiased estimators for the model’s coefficients, i.e. no other technique can produce unbiased slope parameter estimators with lower standard errors (Ramírez, et al. [80] ). The co-integration methodology is also employed to determine the long run relationships among the variables.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 4 provides a descriptive statistics of the variables used in the paper. As reported in the table, the Jargue-Bera probability fails to rejects the null hypothesis of no normally distribution among the variables. Nonetheless, all the series are transformed into natural logarithm to reduce the severity of multicollinearity and serial correlation that might happen among the variables. Likewise, the estimates of correlation coefficient re reported in Table 5. The estimates suggest that the correlation between the ratio of agriculture value added-to-GDP and population growth rate, real exchange rate and trade liberalization or degree of openness is positive. Surprisingly, agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio seems to negatively correlate with FDI-to-GDP ratio, gross fixed capital formation, and per capita GDP. The negative association-ship between the ratio of FDI-to-GDP and the ratio of agriculture value added-to-GDP suggest that, despite a recent substantial amount of both flows and stocks of FDI in the economy of Tanzania, agriculture valued added has been falling. The negative correlations between the ratio of agriculture-to-GDP and real GDP growth on one hand, and real per capita GDP growth on the other hand are very interesting. In fact, these results suggest that the importance of agriculture in the economy has been de clining over time and that over 70 percent of the labour force is neglected. Also, it is surprising that the correlation coefficient suggests a positive association between inflation rate and agriculture-to-GDP ratio.

5.2. Unit Root Tests

A basic assumption of the Classical Linear Regression (CLRM) model requires

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics.

Source: Authors computations (2016).

Table 5. Estimates of Correlation Coefficient.

Source: Authors Computations (2016).

all variables to be stationary. The violation of this assumption leads to spurious regression. To avoid this shortfall, the unit root test with and without trend is conducted on all variables to find out whether they are stationary or non-sta- tionary. The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) method is applied to check for a unit root for all variables in both levels and first differences. The results of these tests are presented in Table 6. The results suggest that the hypothesis of a unit root cannot be rejected in all variables in levels. It is therefore concluded that Agr, FDI, Growth, GFCF, , pGDP, Labour, RER and Trade are non-stationary at their levels. However, the hypothesis of a unit root is rejected in first differences. Hence, all variables are integrated of degree one to make them stationary. This also suggests that, further estimations could be carried while in first difference in order to avoid spurious correlation.

5.3. Testing for Cointegration

Cointegration test examines if the variables have a long run or equilibrium relationship. Having established that the variables are of the same order of integration, the next procedure is to test the possibility of cointegration among the variables used in the model. Trace and Maximum Eigen value are used to determine the presence of co-integration between variables. The results of the cointe gration test are presented in Table 7.

On the basis of the maximum eigen value test, the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected at the 5 percent level of significance in favour of the specific alternative, namely that there is at most six cointegrating vector 2. The implication is that a linear combination of all the eight series is found to be stationary and that there is a stable long-run relationship between the series.

Table 6. Unit Root Testing in Levels and in First Difference.

Source: Authors Computations (2016).

Table 7. Johansen Tests for Cointegration.

Sample: 1992-2015, Lags = 2. Source: Authors computations (2016).

Thus it is concluded that there is a long-run relationship or co-integrated regression between the series.

5.4. Results

5.4.1. Agricultural Sector

Results for agriculture and growth functions are reported in Table 8 and Table 10 respectively. Estimation results presented in Table 8 indicates that the F-statistic is significant at 1 percent, rejecting the null hypothesis that all the regressors have coefficients not different from zero. The Durbin-Watson statistic (DW) of 2.0 fails to reject the null hypothesis of no serial correlation in the regression model. Moreover, adjusted R-squared, which measures the goodness of fit of the variables, is sufficiently large; suggesting that about 67 percent of the variations in agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio is jointly explained by the regressors during the 1990-2015 period. Also, the diagnostic tests show that the error correction model does not suffer from non-normality. Indeed, the histogram and Jarque-Bera normality test as reported in Figure 4 suggest that the residuals of the model are normally distributed. In the same line, the Breusch-Godfrey serial correlation Lagrange Multiplier (LM) and Correlogram Tests confirm that the residual terms in the model are not serially correlated.

Table 8. Estimation Results: Dependent Variable,

Source: Authors computations (2016).

Figure 4. Normality Test of the Residuals: Histogram, Dependent Variable:

Notes: The Normality test indicates that residuals are normally distributed as we unable to reject the null hypothesis of normality using Jacque-Bera at 5 percent. Source: Authors Computations (2016).

Furthermore, the ARCH LM test strongly suggests that there exists no heteroscedasticity in the residual terms of the model. In addition, Ramsey RESET test suggests that the model is specified correctly. Also, cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and CUSUM of squares are used to test the stability of the models. In the use of the CUSUM plots, if the statistics stay within the critical bonds of 5 percent level of significance, the null hypothesis of all coefficients in the given regression are stable and cannot be rejected (Figure 5 & Figure 6). In addition, autocorrelation and partial correlation are used to test for serial correlation (Table 9).

The empirical results show that the coefficient of FDI is statistically insignificant. In fact, agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio did not respond to an increase in FDI inflow-to-GDP ratio over the 1990-2015 periods. It has been evidenced that, despite a significant increase in FDI flows to the economy, a substantial proportion of the FDI activities concentrated in non-agricultural sectors such a mining and quarrying, services, construction and manufacturing. As a result, agriculture value added remains stagnant as both real GDP growth and FDI inflows increase.

Labour as proxied by population growth rate and trade liberalization as proxied by the ratio of import plus export-to-GDP seem to play a great role in agriculture sector in Tanzania. Over the 1990-2015 periods, these factors have positive and statistically significant coefficients. Specifically, holding other factors

Figure 5. Stability Test: CUSUM. Source: Authors Computations.

Figure 6. Stability Test: CUSUM of Squares. Source: Authors Computations.

Table 9. Autocorrelation and Partial Autocorrelation.

Notes: The test for serial correlation using Correlogram indicates that there is no serial correlation in the model. None of the lag is found to be significant at 5 percent level. Source: Authors Computations.

constant, if labour increases by 1 percent, agriculture valued added-to-GDP ratio will increase by 1.2. Similarly, the ratio of agriculture value added-to-GDP will increase by 0.3 percent if trade liberalization increases by 1 percent keeping other variables fixed. Surprisingly and contrary to expectations, gross fixed capital formation seems to have a negative effect on agriculture. The coefficient of gross fixed capital formation is negative and statistically significant at 1 percent level. This suggests that if gross fixed capital formation-to-GDP ratio increases by 1 percent, the ratio of agriculture valued added-to-GDP will decline by 0.6 ceteris paribus.

Moreover, the empirical results suggest that if real GDP growth increases by 1 percent, agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio will decrease by 0.06 percent. This negative effect of economic growth on agriculture may not be very surprising but it is interesting. The improvement in the economy does not significantly support agriculture sector. In fact, the importance of agriculture sector to the economy of Tanzania has declined especially over the last 25 years despite the fact that it forms the basis for food security and that over 70 percent of the population lives in rural areas where agriculture and related non-farm activities are their main occupation. In addition, agriculture produces materials for agro- processing industries which are the main types of industries under the current level of development in Tanzania.

5.4.2. Economic Growth

A priori, the results as reported in Table 10 suggest that the equation estimated is of good fit and powerful. The adjusted coefficient of determination, suggests that 40 percent of the variation in real GDP growth is jointly explained by the factors included in the estimation model. Besides, the estimated F-statistic is high and statistically significant at 1 percent level rejecting the null hypothesis

Table 10. Estimation Results: Dependent Variable, .

Source: Authors computations (2016).

that all the explanatory variables have coefficients equal to zero. This suggests that the model estimated has good overall explanatory power. In addition, the estimated p-value for RESET regression errors specification test fails to reject the null hypothesis of no model misspecification error. Also, the DW of 2 suggests that multicollinearity is not a problem in the estimated model. Furthermore, diagnostic tests show the residuals are normally distributed (Figure 7), the coefficients are stable (Figure 8 and Figure 9) and that, there is no serial correlation among residuals (Table 11).

The sign of the coefficient of agriculture value added-to-GDP ratio is negative and statistically significant at 1 percent level. These results are surprising but support the argument that agriculture is increasingly becoming less important to economic growth in Tanzania. These circumstances, however posse questions on the sustainability of agriculture employment and food security in the country. As expected however, the results obtained from the growth equation show that the coefficient of the FDI has the correct sign and is significantly different from zero at the 1 percent level, as is the coefficient for the degree of trade liberalization which is also statistically significant at the 1 percent level. A 1 percent increase in FDI-to-GDP ratio and trade-to-GDP ratio may lead a 0.17 percent and 2.56 percent increase in real GDP growth respectively, other factors being equal. The growth in the labour force seems to have a negative impact on the growth of the economy. The coefficient for the labour force is significant different from zero at the 1 percent level suggesting that a 1 percent increase in labour force may reduce real GDP growth by 1.9 percent ceteris paribus. Notwithstanding, this may have something to do with the fact that the study proxies the labour force with

Figure 7. Normality Test of the Residuals: Histogram, Dependent Variable:

Notes: The Normality test indicates that residuals are normally distri- buted as we unable to reject the null hypothesis of normality using Jacque-Bera at 5 per- cent. Source: Authors computations.

Figure 8. Stability Test: CUSUM. Source: Authors Computations.

Figure 9. Stability Test: CUSUM of Squares. Source: Authors Computations.

Table 11. Autocorrelation and Partial Autocorrelation.

Notes: The test for serial correlation using Correlogram indicates that there is no serial correlation in the model. None of the lag is found to be significant at 5 percent level. Source: Authors Computations.

the population level (see Reinhart and Khan [81] ). This is due to the fact that growth of labour force and population growth undoubtedly correlated. The negative effect of labour force as proxied by population is broadly consistent with previous studies such Malthus [73] and Tsen & Furuoka [72] .

Unsurprisingly, inflation has a negative effect on economic growth. These results are consistent with the view that uncertainty about price developments mainly influences growth via distortions in the allocation of resources and via discouraging the overall accumulation of physical capital, while high levels of inflation may discourage saving and investment leading to low real GDP growth. The increase in the real exchange rate apparently does not exert a significant effect on the real GDP growth in Tanzania during the sample period.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This paper is confined to FDI inflows, agricultural agriculture value added as a percent of GDP and economic growth in Tanzania during the 1990-2015 periods. During this period, the government of Tanzania attracted a substantial amount of FDI through various incentives such as the establishment of Tanzania Investment Policy. The paper aims at investing the effect of FDI inflows on agriculture sector on one hand, and the relationship between agriculture sector and FDI and real GDP growth on the other hand. FDI-to-GDP ratio, agriculture value added-to-GDP and real GDP growth apart, the control variables included in the models are gross fixed capita formation, population growth rate (labour), real exchange rate, inflation and the ratio of imports plus export-to-GDP (degree of trade liberalization or openness). Time series data spanning from 1990 to 2015 are used for estimation and analysis. Data are obtained from UN Statistics Division, World Bank World Development Indicators, UNCTAD, World Investment Report, Bank of Tanzania and Tanzania Investment Centre.

The empirical findings suggest that there is no effect of FDI on agriculture value added; however, the relationship between FDI and real GDP growth is positive. It is also revealed that the correlation between agriculture value added and real economic growth is negative and strong. The positive effect of FDI on overall economic growth and the negative association between agriculture sector and economic growth imply that a recent improvement in the economy of Tanzania is due to improvement in the growth of non-agricultural sectors. However, due to the fact that agricultural sector employs more than 70 percent of total labour force but contributes about 30 percent of total GDP, the sector is inefficient. The sector attracts very low proportion of FDI inflows to Tanzania. Understandably, FDI flows to agriculture may give different opportunities such as farm knowledge transfer, improved infrastructures and creation of new markets local and foreign.

The sector currently is dominated by smallholders such as horticulture, small-scale farming of cash and food crops but also animal keeping. Due to the fact that agriculture employs the largest percent of Tanzanian population, improvement in this area, by implications, may lead to immense reduction of poverty which is critical to most of the citizens at the moment. More efforts to promote incorporation and creation of strong bonds between smallholders and investors can ultimately increase FDI to the sector and thus increase productivity and food security.

Cite this paper

Epaphra, M. and Mwakalasya, A.H. (2017) Analysis of Foreign Direct Investment, Agricultural Sector and Economic Growth in Tanzania. Modern Economy, 8, 111-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/me.2017.81008

References

- 1. Loungani, P. and Razin, A. (2001) How Beneficial Is FDI for Developing Countries? Finance & Development: A Quarterly Magazine of IMF, 38. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2001/06/loungani.htm

- 2. Kumar, M.M. (2014) FDI and Indian Economic Growth Factors—An Empirical Analysis. International Journal of Management and Commerce Innovations, 2, 7-18.

- 3. Rutihinda, C. (2007) Impact of Globalization on Small and Medium Size Firms in Tanzania. ABR & TLC Conference Proceedings, Hawaii, USA.

- 4. Dollar, D. and Kraay, A. (2002) Growth Is Good for the Poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 7, 195-225. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020139631000

- 5. FAO (2012) Trends and Impacts of Foreign Investment in Developing Country Agriculture: Evidence from Case Studies. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

- 6. Heumesser, C. and Schmid, E. (2012) Trends in Foreign Direct Investment in the Agricultural Sector of Developing and Transition Countries. Universitat für Bodenkultur, Wien.

- 7. UNCTAD (2015) Economic Development in Africa: Rethinking the Role of Foreign Direct Investment. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Geneva, Switzerland, United Nations Publication.

- 8. United Republic of Tanzania (2015) The Economic Survey 2012. Ministry of Finance, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

- 9. The World Bank, World Development Indicators (2016) Gross Domestic Product. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD

- 10. Tanzania Investment Centre (2015) Tanzania Investment Report, Foreign Private Investment. Bank of Tanzania, Tanzania Investment Centre, Zanzibar Investment Promotion Authority and National Bureau of Statistics.

- 11. Amani, H. and Mkumbo, E. (2012) Strategic Research on the Extent to Which Tanzania Has Transformed Its Rural Sector for Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction. REPOA 17th Annual Research Workshop, the Whitesands Hotel, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 28-29 March 2012.

- 12. SET (2015) Tanzania: Data on Economic Transformation. Supporting Economic Transformation. set.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Tanzania2.docx

- 13. Msuya, E. (2007) The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Agricultural Productivity and Poverty Reduction in Tanzania. Kyoto University, Kyoto. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/3671/

- 14. Rao, D.S., Timothy, J.C. and Alauddin, M. (2004) Agricultural Productivity Growth, Employment and Poverty in Developing Countries, 1970-2000. International Labour Organization, Employment Strategy Papers.

- 15. Alston, M.J., Wyatt, T.J., Pardey, P.G., Marra, M.C. and Chan-Kang, C. (2000) A Meta-Analysis of Rates of Return to Agricultural R & D, Ex Pede Herculem? Research Report 113, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC.

- 16. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2015) World Investment Report 2015, Reforming International Investment Governance, United Nations, New York & Geneva. http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2015_en.pdf

- 17. Portelli, B. (2005) The Role of Foreign Direct Investment in the Context of Economic Reform. Evidence from Tanzania. Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, University of Oslo, Oslo.

- 18. Tanzania Investment Centre (2013) Tanzania Investment Report, Foreign Private Investment. Bank of Tanzania, Tanzania Investment Centre, Zanzibar Investment Promotion Authority and National Bureau of Statistics.

- 19. Ministry of Agriculture Food Security and Cooperatives (2008) Agriculture Sector Review and Public Expenditure Review 2008/09, United Republic of Tanzania.

- 20. UNESCO (2012) Agriculture: Green Revolution to Improve Productivity. [Online] http://www.natcomreport.com/Tanzania/pdf-new/agriculture.pdf

- 21. Collier, P. and Dercon, S. (2009) African Agriculture in 50 Years: Smallholders in a Rapidly Changing World. Paper Presented at the Expert Meeting on How to Feed the World in 2050, FAO, Rome, 24-26 June 2009.

- 22. Schüpbach, J.M. (2014) Foreign Direct Investment in Agriculture: The Impact of Out Grower Schemes on Large-Scale Farm Employment on Economic Well-Being in Zambia. PhD Thesis, No. 22287, University of Zurich, Zurich. e-collection.library.ethz.ch/eserv/eth:47518/eth-47518-02.pdf

- 23. UNCTAD (2009) World Investment Report 2009, Transnational Corporations, Agricultural Production and Development. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Geneva, 17 September 2009.

- 24. FAO (2013) Analysis of Public Expenditures on Support of Food and Agriculture Development in the United Republic of Tanzania, 2006/07-2010/11. Monitoring African Food and Agricultural Policies. https://agriknowledge.org/downloads/ng451h506

- 25. Tanzania Investment Centre and National Bureau of Statistics (2013) Statistical Abstract United Republic of Tanzania. http://www.nbs.go.tz/nbs/Stastical%20Abstract/

- 26. World Bank (2016) New Project to Link Farmers to Agribusiness in Tanzania. World Bank. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2016/03/10/new-project-to-link-farmers-to- agribusiness-in-tanzania

- 27. Blomstrom, M. and Kokko, A. (2003) The Economics of Foreign Direct Investment Incentives. NBER Working Papers 9489, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge. econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:hhs:eijswp:0168 https://doi.org/10.3386/w9489

- 28. Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J. and Lee, J. (1998) How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Economic Growth? Journal of International Economics, 45, 115-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(97)00033-0

- 29. Adewumi, S. (2006) The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Growth in Developing Countries: An African Experience. Jonkoping International Business School, Jonkoping University, Jonkoping.

- 30. Klein, M., Aaron, C. and Hadjimichael, B. (2001) Foreign Direct Investment and Poverty Reduction. Policy Research Working Paper, World Bank eLibrary. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-2613

- 31. Chen, Y. and Démurger, S. (2002) Foreign Direct Investment and Manufacturing Productivity in China. CEPII Research Project on the Competitiveness of China’s Economy.

- 32. FAO (2001) Agricultural Investment and Productivity in Developing Countries. Economic and Social Development Paper 148. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/003/x9447e/x9447e.pdf

- 33. Oleyede, B.B. (2014) Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Agricultural Development in Nigeria, (1981-2012). Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 3, 14-24. http://www.arabianjbmr.com/pdfs/KD_VOL_3_12/2.pdf

- 34. FAO (2014) Impact of Foreign Agricultural Investment on Developing Countries: Evidence from Case Studies. FAO Commodity and Trade Policy Research Working Paper No. 47. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3900e.pdf

- 35. Rakotoarisoa, M.A. (2011) A Contribution to the Analysis of the Effects of Foreign Agricultural Investment on the Food Sector and Trade in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/est/PUBLICATIONS/Comm_Working_Papers/ Working_paper_33.pdf

- 36. Almfraji, M.A. and Almsafir, M.K. (2014) Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth Literature Review from 1994 to 2012. Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 129, 206-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.668

- 37. Gorgen, M., Rudloff, B., Simons, J., Ullenberg, A., Vath, S. and Wimmer, L. (2009) Foreign Direct Investment in Land in Developing Countries. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Germany, Division 45 Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. https://www.giz.de/fachexpertise/.../giz2010-en-foreign-direct-investment-dc.pdf

- 38. Yiyong, C., Gunasekera, D. and Newth, D. (2015) Effects of Foreign Direct Investment in African Agriculture. China Agricultural Economic Review, 7, 167-184. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-08-2014-0080

- 39. Findlay, R. (1978) Relative Backwardness, Direct Foreign Investment and the Transfer of Technology: A Simple Dynamic Model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 92, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.2307/1885996

- 40. Wang, J.Y. and Blomstrom, M. (1992) Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer: A Simple Model. European Economic Review, 36, 137-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(92)90021-N

- 41. UNCTAD (2001) Trade and Investment Report. The United Nations, New York.

- 42. Alfaro, L. (2003) Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: Does the Sector Matter? Working Paper, Harvard Business School, Harvard. http://www.grips.ac.jp/teacher/oono/hp/docu01/paper14.pdf

- 43. Khadaroo, A.J. and Seetanah, B. (2010) Transport Infrastructure and Foreign Direct Investment. Journal of International Development, 22, 103-123. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1506

- 44. Tanzania Investment Centre (2014) Tanzania Investment Report, Foreign Private Investment. Bank of Tanzania, Tanzania Investment Centre, Zanzibar Investment Promotion Authority and National Bureau of Statistics.

- 45. Adhikary, B.K. (2011) FDI, Trade Openness, Capital Formation, and Economic Growth in Bangladesh: A Linkage Analysis. International Journal of Business and Management, 6, 16-28. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v6n1p16

- 46. United Nations Statistics Division (2016) UNSD Statistical Databases. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/databases.htm

- 47. Bank of Tanzania (2013) Annual Report (2012/13) Directorate of Economic Research and Policy, Bank of Tanzania, United Republic of Tanzania.

- 48. Feldstein, M. (2000) Aspects of Global Economic Integration: Outlook for the Future. NBER Working Paper No. 7899, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- 49. Akulava, M. and Vakhitova, G. (2010) The Impact of FDI on Firm’s Performance across Sectors: Evidence from Ukraine. Kyiv School of Economics, No. 26. econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:kse:dpaper:26

- 50. Singaariya, M.R. and Sinha, N. (2015) Relationships among Per Capita GDP, Agriculture and Manufacturing Sectors in India. Journal of Finance and Economics, 3, 36-43. pubs.sciepub.com/jfe/3/2/2/

- 51. Anderson, C.L. (1987) The Production Process: Inputs and Wastes. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 14, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0095-0696(87)90001-5

- 52. Krugman, P.R. (1990) Rethinking International Trade. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- 53. Miller, S.M. and Upadhyay, M.P. (2000) The Effects of Openness, Trade Orientation and Human Capital on Total Factor Productivity. Journal of Development Economics, 63, 399-423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(00)00112-7

- 54. Baily, M.N. and Gersbach, H. (1995) Efficiency in Manufacturing and the Need for Global Competition. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics, 1995, 307-358. https://doi.org/10.2307/2534776

- 55. De Silva, N., Malaga, J. and Johnson, J. (2013) Trade Liberalization Effects on Agricultural Production Growth: The Case of Sri Lanka. Southern Agricultural Economics Association Annual (SAEA) Meeting, Orlando, Florida, 2-5 February 2013.

- 56. Hassine, N.B., Robichaud, V. and Decaluwe, B. (2010) Agricultural Trade Liberalization, Productivity Gain, and Poverty Alleviation: A General Equilibrium Analysis. Economic Research Forum, Working Paper No. 519, Cairo, Egypt.

- 57. Jayanthakumaran, K. (2002) The Impact of Trade Liberalisation on Manufacturing Sector Performance in Developing Countries: A Survey of the Literature. Working Paper 02-07, Department of Economics, University of Wollongong, Wollongong.

- 58. Dollar, D. (1992) Outward-Oriented Developing Economies Really Do Grow More Rapidly: Evidence from 95 LDCs, 1976-1985. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 40, 523-544. https://doi.org/10.1086/451959

- 59. Frankel, J. and Romer, D. (1999) Does Trade Cause Growth? American Economic Review, 89, 379-399. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.3.379

- 60. Dollar, D. and Kraay, A. (2002) Trade, Growth, and Poverty. The Economic Journal, 114, F22-F49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0133.2004.00186.x

- 61. Bhagwati, J. and Srinivasan, T.N. (2001) Outward-Orientation and Development: Are the Revisionists Right? In: Lal, D. and Snape, R.H., Eds., Trade, Development, and Political Economy: Essays in Honour of Anne O. Krueger, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 3-26.

- 62. Wacziarg, R. and Welch, K.H. (2003) Trade Liberalization and Growth: New Evidence’ National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper No. 10152, Washington, DC.

- 63. Rodrik, D. (1996) Understanding Economic Policy Reform. Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 9-41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2729408

- 64. Rodríguez, F. and Rodrik, D. (2001) Trade Policy and Economic Growth: A Skeptic’s Guide to the Cross-National Evidence. In: Bernanke, B.S. and Rogoff, K., Eds., NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2000, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

- 65. Lotfalipour, R.M., Ashena, M. and Zabihi, M. (2013) Exchange Rate Impacts on Investment of Manufacturing Sectors in Iran. Business and Economic Research, 3, 12-22. https://doi.org/10.5296/ber.v3i2.3716

- 66. Bassanini, A. and Scarpetta, S. (2001) The Driving Forces of Economic Growth: Panel Data Evidence for the OECD Countries. OECD Economic Studies, 33, 9-56. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-v2001-art10-en

- 67. Edey, M. (1994) Costs and Benefits from Moving from Low Inflation to Price Stability. OECD Economic Studies, No. 23, 109-130. https://www.oecd.org/eco/monetary/33929490.pdf

- 68. Bruno, M. and Easterly, W. (1998) Inflation Crises and Long-Run Growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 41, 3-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(97)00063-9

- 69. De Sormeaux, A. and Pemberton, C. (2011) Factors Influencing Agriculture’s Contribution to GDP: Latin America and the Caribbean. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago.

- 70. Chaudhry, I.S., Ayyoub, M. and Imran, F. (2013) Does Inflation Matter for Sectoral Growth in Pakistan? Pakistan Economic and Social Review, 51, 71-92.

- 71. Pemberton, C. (2002) A Population Growth Theory of Rural Development. In Rural Development Challenges in the Next Century. Proceedings of the International Conference of ALACEA-The Latin American and Caribbean Association of Agricultural Economists, edited by Carlisle A. Pemberton, 214-227. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, UWI, St Augustine. Trinidad and Tobago.

- 72. Tsen, W.H. and Furuoka, F. (2005) The Relationship between Population and Economic Growth in Asian Economies. ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 22, 314-330. https://doi.org/10.1355/AE22-3E

- 73. Malthus, T.R. (1798) An Essay on the Principle of Population, As It Affects the Future Improvement of Society: with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorset, and Other Writers. London. http://www.esp.org/books/malthus/population/malthus.pdf

- 74. Jhingan, M.L. (2006) Economic Development. Vrinda Publications Ltd., New Delhi.

- 75. Ainabor, A.E., Shuaib, I.M. and Kadiri, A.K. (2014). Impact of Capital Formation on the Growth of Nigerian Economy 1960-2010: Vector Error Correction Model (VECM). School of Business Studies, Readings in Management and Social Studies, 1, 132-154.

- 76. Kormendi, R.C. and Meguire, P.G. (1985) Macroeconomic Determinants of Growth: Cross-Country Evidence. Journal of Monetary Economics, 16, 141-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(85)90027-3

- 77. Barro, R.J. (1991) Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 407-443. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937943

- 78. Levine, R. and Renelt, D. (1992) A Sensitivity Analysis of Cross-Country Growth Regressions. American Economic Review, 82, 942-963. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2117352

- 79. Kendrick, J.W. (1993) How Much Does Capital Explain? In: Szirmai, A., Van Ark, B. and Pilat, D., Eds., Explaining Economic Growth, Essays in Honour of Angus Maddison, North Holland, Amsterdam, 129-146.

- 80. Ramírez, O.A., Misra, S.K. and Nelson, J. (2003) Efficient Estimation of Agricultural Time Series Models with Nonnormal Dependent Variables. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 85, 1029-1040. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8276.00505

- 81. Khan, M.S. and Reinhart, C.M. (1989) Private Investment and Economic Growth in Developing Countries. International Monetary Fund, Research Department, WP/89/60.

NOTES

1The data from UNCTAD categorize FDI to agriculture as those related to crops, livestock, fishing, forestry and hunting.

210 This is because the first significant value, where trace statistic is less than critical value at 5 percent level, is found at maximum rank of six.