American Journal of Plant Sciences

Vol.4 No.5(2013), Article ID:32132,9 pages DOI:10.4236/ajps.2013.45125

Effect of Different Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Maize Seed Germination and Seedling Development

![]()

1Laboratoire de Biologie et de Typage Moléculaire en Microbiologie, Département de Biochimie et de Biologie Cellulaire, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Bénin; 2Centre de Recherches Agri-coles Sud, Institut National des Recherches Agricoles du Bénin, Attogon, Bénin; 3Laboratoire de Défense des Cultures, Centre de Recherches Agricoles d’Agonkanmey, Institut National des Recherches Agricoles du Bénin, Cotonou, Bénin; 4Department of Biology, The State University of New Jersey, Camden, USA; 5Center for Computational and Integrative Biology, The State University of New Jersey, Camden, USA.

Email: *laminesaid@yahoo.fr

Copyright © 2013 Pacôme A. Noumavo et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received March 23rd, 2013; revised April 27th, 2013; accepted May 15th, 2013

Keywords: Azospirillum; Pseudomonas; PGPR, Biofertlization; Maize Seeds; Germination; Greenhouse

ABSTRACT

Our study aimed at assessing the effects of 3 Plants Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) either singly or in combination on maize growth under laboratory and greenhouse conditions. Seeds were inoculated with single and combined solution of 108 CFU/ml of Rhizobacteria. Seeds were not inoculated for the control variant. The highest germination percentage was obtained with the combination of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida. This combination also recorded the best vigor index, plants circumferences number of leaves and the leaf area. The maximal heights of plants were observed with seeds treated with Azospirillum lipoferum with an increase of 37.32%. The highest rates of underground dry matter were recorded with A. lipoferum, with an increase of more than 56% comparative to control, while the combination P. fluorescens and P. putida increased the aerial dry matter of 59.11%. Finally, the highest value of the aerial biomass was obtained with the plants treated with the combination of P. fluorescens and P. putida and the highest underground biomass was obtained with plants treated only with A. lipoferum. These results suggest that specific combinations of PGPR can be considered as efficient alternative biofertilizers to promote maize seed germination, biomass and crop yield.

1. Introduction

Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) is a group of bacteria that actively colonize plant roots and increase plant growth and yield [1]. The mechanisms they use to promote plants growth are not fully understood, but they can be classified in four groups: biofertilizers (solubilisation of mineral phosphates, asymbiotic N2 fixation) [2, 3], phytostimulators (abilityto produce phytohormones) [4], rhizoremediators (degrading organic pollutants) [5] and biopesticides (production of siderophores, the synthesis of antibiotics, enzymes and/or fungicidal compounds) [6-8].

Nowadays, the plants inoculation with rhizobacteria PGPR is a major asset for biological agriculture. This environmental biotechnology is also receiving attention as a way to reduce chemical fertilizer doses without affecting crop yield. It can then be evaluated as a component of integrated management strategies in agriculture [9-11]. The first observations of PGPR effects on the seeds have been realized with Pseudomonas spp. isolated from roots. In California and Idaho, [12] obtained a statistically significant increase of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) yield from 14% to 33% in 59 fields with seeds treated with Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida suspension. It has been also shown that Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas fluorescens strains can increase root and shoot elongation in canola [13], wheat and potato [14,15]. Azospirillum species are prominent Plant GrowthPromoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) used as inoculants for phytostimulation of several types of crops (mainly cereals) under different climatic conditions and they may lead to improved crop yields [16,17]. Then, with maize, Azospirillum lipoferum CRT1 is the most important PGPR used in Europe [10,18,19] whereas in Mexico (one of the leading countries in field inoculation) Azospirillum brasilense UAP-154 and CFN-535 inoculants are extensively used under agronomic conditions [11,17]. Several studies have been carried out to determine the effect of PGPR on plant but very few have invoved parameters of seed germination well as plant growth. The impact of those PGPR’s combinations has not yet been well studied. We hypothesize that by combining PGPR with different metabolic capacities (N2 fixation, P mobilization, production of phytohormones, and antimicrobials, etc.), we can expect additive or synergistic effects resulting from their combination and hence better improvement of the crop growth. In the same way, [20] asserted that the combination of Azospirillum, Pseudomonas and Azotobacter strains could affect seed germination.

In this context, we assessed the effects of three different PGPR either singly or in combination (Azospirillum lipoferum, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida) on maize seed germination and growth development under laboratory and greenhouse growth conditions.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

The bacteria species used were Azospirillum lipoferum, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida. The maize seeds used were a composite of 85 - 90 days cycle variety called EVDT 97 STR C1S [21]. The soil used in green house experiments was a deep reddish ferrous non damaged soil.

2.2. Preparation of PGPR Inoculum

The PGPR used were those isolated and identified by [22]. Unless in use, the bacteria stocks were kept at −20˚C in Muller Hinton broth with 10% of Glycerol throughout. The PGPR suspensions were prepared using a modified method of [23]. The bacteria were cultured onnutrient broth platesduring 48 h at 30˚C (Pseudomonas lipoferum and Pseudomonas putida) and at 37˚C (Azospirillum lipoferum). Two days old cultures were harvested and centrifuged at 10.000 rpm for 10 min. Pellets obtained were suspended in nutrient broth and the inoculums load was adjusted to 1 × 108 CFU/ml using the spectrophotometer. For treatments with a combination of two or three bacteria, inoculum of each PGPR was adjusted to the required concentration and then they were mixed in the ratio of 1:1 (v/v) prior to inoculation.

2.3. Seed Inoculation with PGPR

Maize seeds were surface sterilized with 0.024% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min and rinsed thoroughly in sterile distilled water under agitation [24]. The surface sterilized seeds were treated with different PGPR suspensions of about 1 × 108 CFU/ml for 30 min [25].

2.4. Experimental Design

Eight variants with three replications were considered for the experiment: CTL = Control (without rhizobacteria); Azo: treated only with Azospirillum lipoferum; P1: treated only with Pseudomonas fluorescens; P3: treated only with Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens in the same proportion; AzoP3: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas putida in the same proportion; P1P3: treated both with Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida in the same proportion; AzoP1P3: treated with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescensPseu-domonas putida in the same proportion (1:1:1).

2.5. In Vitro Seeds Germination

Twenty seeds of maize inoculated with PGPR were arranged in an equidistant manner in a sterile square Petri dish (11.8 cm of side) (Figure 1).

2.6. PGPR Effect on Maize Growth

2.6.1. Chemical Characteristics of the Soil

Ten grams of soil suspended in 25 ml distilled water were used to determine the pH of the soil [26]. The assimilable phosphorus was been determined by color method at 660 nm [27], while exchangeable cations (Ca, Mg and K) were determined by the ammonium acetate

Figure 1. Paper towel-aided seed germination device.

method as previously described by [28]. The organic carbon was evaluated by [29] method that included oxidation of the organic matter of soil with dichromate of potassium (K2Cr2O7 1N).

2.6.2. Sowing and Maintenance of the Plants

The used soil was sterilized twice at 120˚C for 20 min with 24 hours times’ interval [24]. Two kilograms of sterilized soil were weighed in each plastic pot of 15 cm of diameter. Pots were kept in the greenhouse. Each pot was dampened to 2/9 of the maximal retention capacity of the soil 24 hours before the seeding [30]. A 5cm deep hole was opened in the centre ofeach pot. Two maize seeds (EVDT 97 STR C1) were introduced into the hole and immediately inoculated with 10 ml of each PGPR suspension containing about 1 × 108 CFU/ml, and the hole was then covered with soil. The pots were watered daily at 1/9 of the maximal retention capacity of the substrate. On the 14th Day after Seeding (DAS), the least vigorous of the two plants was removed. Different parameters were measured from the 14th up to the 30th DAS. The average day and night temperatures were 29.44˚C and 21˚C respectively throughout this study.

2.6.3. Assessment of the Growth Parameters

Plant height and stem circumference were measured every 96 h from the 14th to the 30th DAS. These parameters allowed us to assess the plant vigor over growing period. The number of leaves was also measured at different post germination times. Leaf area determination was assess using the classical formula (k × length × width, where k = 0.75) according to [31]. The shoot biomass was also assessed at 30 days post germination. The root biomass of the plants was assessed after carefully recovering the root from the soil and immerging them into water. The plant fresh materials were incubated at 65˚C for 72 hours [25] in order to determine the biomass dry weights, which are expressed in (%) of the fresh biomass.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The collected data were subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) least Significant Difference (LSD) test at probability level 0.05 and to the test of Student Newman-Keuls with Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 8.1) software to evaluate the effects of the PGPR on maize germination and growth. In this model of analysis, the eight treatments were considered as a stationary factor whereas the repetitions were considered as an uncertain factor.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of the PGPR on Seeds Germination

Our data revealed that PGPR treatment promotes maize (Zea mays L.) seed germination (Table 1). We noticed a very significant differences (p < 0.01) in shoot length among the different treatments. The differences in the treatments for germination percentage, root length and vigor index, were highly significant (p < 0.001) compared to the control. The highest germination percentage (100%) was observed with the seeds inoculated with the combination of P. fluorescens-P. putida follow by those inoculated with A. lipoferum (98.33%).

These two treatments increased germination by 22.44%

Table 1. In vitro PGPR effect on maize seeds germination root and shoot length at 7 DAG.

m = Means, Cv = Coefficients of variation, * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001. In a column, the means with different letters are significantly different with probability level of 5 % according to Student Newman-Keuls test.

CTL: Control (without rhizobacteria); Azo: treated only with Azospirillum lipoferum; P1: treated only with Pseudomonas fluorescens; P3: treated only with Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens; AzoP3: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas putida; P1P3: treated both with Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1P3: treated with Azospirillum lipoferum, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas putida in the same proportion (1:1:1).

and 20.39% respectively compared to the control. The highest shoot length was obtained from treatment with the combination of P. fluorescens-P. putida. The highest root length was obtained from seeds inoculated with A. lipoferum with an increasingof 51.53% compared to the control. The best vigor index (Figure 2) was obtained from seeds inoculated with the combination P. fluorescens-P. putida followed by that inoculated with A. lipoferum.

3.2. Chemical Characteristics of Soil

The chemical characteristics of the used soil are presented in the Table 2. The sum of the bases was 5.48 cmol/100 g of soil. The soil was poor in phosphorus, organic carbon and calcium, but rich in potassium.

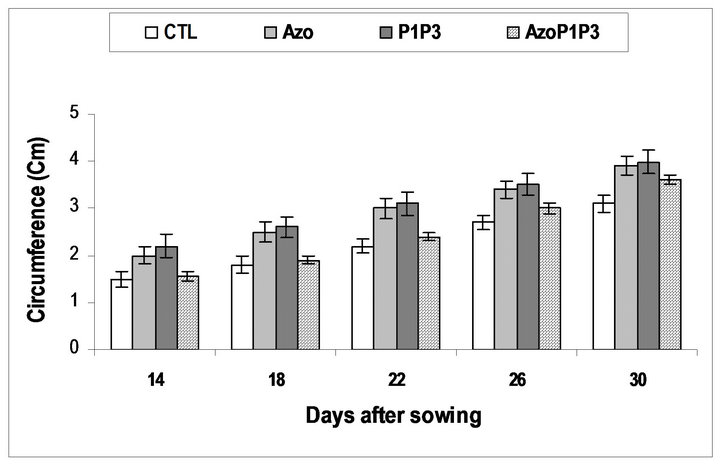

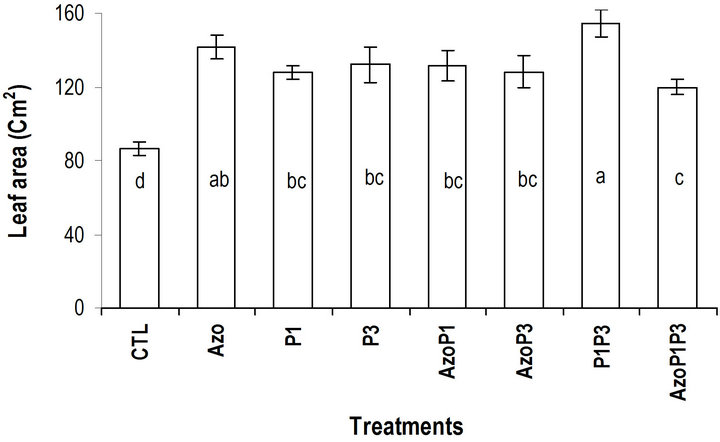

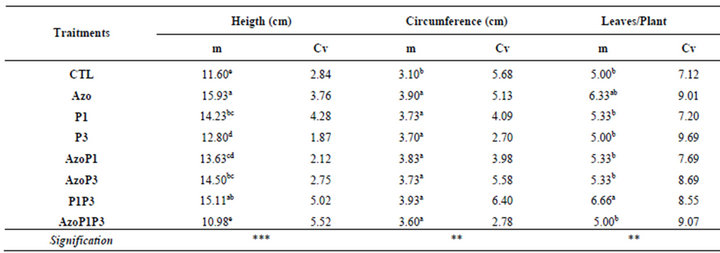

3.3. Effects of PGPR on Plant Growth

Inthe greenhouse, the inoculated seeds with a single strain or the mixed strains of the bacteria grew better and bigger than the non-inoculated seeds during the experiment (14DAS to 30DAS), while the inoculated seeds with the mixed of the 3 types of bacteria grew similarly to the non-inoculated seeds (Figure 3). At 30 DAS the height of the plants in all treatments was significantly different from the control except for treatment AzoP1P3 which was similar to the control. For the circumference of the leaves, significant difference was obtained between treatments (Table 3). The highest circumference of leaves was obtained for the P1P3 treatment.

Plants treated with A. lipoferum had the highest height followed by those treated with a combination of P. flurescens-P. putida. Thereis no significant difference be

CTL: Control (without rhizobacteria); Azo: seeds treated only with Azospirillum lipoferum; P1: seeds treated with Pseudomonas fluorescens; P3: seeds treated with Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1: seeds treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens; AzoP3: seeds treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas putida; P1P3: seeds treated both with Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1P3: seeds treated with Azospirillum lipoferum, Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida

Figure 2. In vitro PGPR Effect on maize vigor indexat 7 DAG.

tween treatments A. lipoferum and the treatment P. fluorescens-P. putida, for plant height, leaf circumference and leaf area (Figures 3-5 and Table 3).

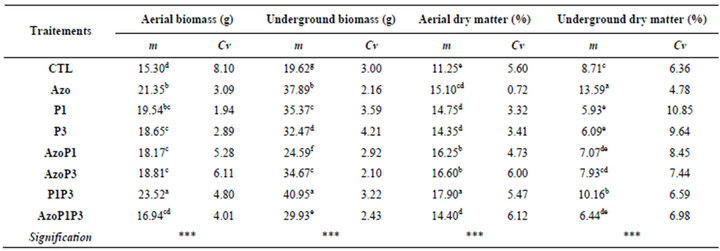

3.4. Effect of PGPR on the Biomass of Maize Plants

PGPR bacteria increased the fresh maize plant weight in all treatments compared to the control. Significant differences were obtained between treatments for aerial and underground biomass and dry matter (Table 4).

The highest biomass was obtained with plants treated with combination of P. fluorescens-P. putida. The biomass has increased by 53.72% and 108%, respectively compared to the control. Although the highest root fresh weight was obtained with the treatment of P. fluorescensP. putida and the highest root dry weight was obtained from pants treated with A. lipoferum (Table 4).

Figure 3. Height of maize plants grown from seeds inoculated by PGPR.

CTL: Control (without rhizobacteria); Azo: treated only with Azospirillum lipoferum; P1P3: treated both with Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1P3: treated with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida. in the same proportion (1:1:1).

Figure 4. Maize plants inoculated with PGPR circumference evolutionary tendency.

CTL: Control (without rhizobacteria); Azo) : treated only with Azospirillum lipoferum; P1: treated only with Pseudomonas fluorescens; P3: treated only with Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens; AzoP3: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas putida; P1P3: treated both with Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1P3: treated with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida in the same proportion (1:1:1)

Figure 5. Effects of PGPR on maize leaf area 30 DAS.

4. Discussion

The present study confirms the beneficial effects of the PGPR on crops. Treatment with the combination of P. fluorescens and P. Putida 22.44% compared to the control.

This improvement of the germination percentage observed in our study, may be due to an increase of the synthesis of the hormone gibberellin, which Trigg the activity of α-amylase and other germination specific enzymes like protease and nuclease involved in hydrolysis and assimilation of the starch [24]. It could also be as a result of better activity of mitochondrial enzymes accompanied by an increase of the oxygen consumption. [32] showed the advantage and efficiency of rhizobacteria combination on germination of wheat seeds. They obtained the best germination percentages when seeds were treated with Azotobacter WPR-51 and the combination Azospirillum WM-3-Azotobacter WPR-51-Azospirillum PR42, which led to an increase of 81.81% compared tothe control. [32] also noticed a reduction in germination time when seeds were inoculated with PGPR.

All treatments with PGPR in our study increased the vigor indexof maize seeds7 days after germination (Figure 2).

The seeds inoculated with the combination of P. fluorescens-P. putida showed the highest vigor index (Figure 2), which was 77.54% higher than the control. The findings by [24] and [23] on the maize and safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) respectively corroborate the results obtained in our study. [24] found that Azospirillumbrasilense DSM 1690, P. putida R-168 and P. fluo-

Table 2. Chemical characteristics of soil used for maize growth.

Table 3. PGPR effects on maize plants height, circumference and number of leaves at 30 DAG.

m = Means, Cv =Coefficients of variation, * = p < 0.05 ; ** = p < 0.01 ; *** = p < 0.001. In a column, the means with different letters are significantly different with probability level of 5% according to Student Newman-Keuls test.

CTL: Control (without rhizobacteria); Azo: Azospirillum lipoferum; P1: Pseudomonas fluorescens; P3: Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens; AzoP3: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas putida; P1P3: treated both with Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1P3: treated with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida. in the same proportion (1:1:1)

Table 4. PGPR effects on maize plants biomass and dry matter at 30 DAS.

m = Means, Cv = Coefficients of variation, * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001. In a column, the means with different letters are significantly different with probability level of 5% according to Student Newman-Keuls test.

CTL: Control (without rhizobacteria); Azo: treated only with Azospirillum lipoferum; P1: treated only with Pseudomonas fluorescens; P3: treated only with Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens; AzoP3: treated both with Azospirillum lipoferumPseudomonasputida; P1P3: treated both with Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida; AzoP1P3: treated with Azospirillum lipoferum-Pseudomonas fluorescens-Pseudomonas putida in the same proportion (1:1:1).

rescens R-93 significantly increased the vigor index of maize significanty compared to the control, and [23] obtained similar resuts with P. fluorescens. This high vigor index may be due to a better production and metabolism of auxin, hormones responsible of the cellular elongation [7] or cytokinin, hormones that stimulate the cellular division [33] triggered by PGPR treatment.

The soil pH is 6 and Magnesium (2.22 meq/100 g) were similar to those (5.8 and 2.07 mg-eq/100 g) obtained by [34]. However, the soil potassium content (2.01 mg-eq/100 g) was higher than the value (0.74 mg-eq/100 g) obtained by previously authors. The soil contents in phosphorus (20.54 ppm), organic carbon (1.16%) and calcium (1.25 meq/100 g) obtained in this study was lower than those (67.00 ppm 2.987% and 2.40 mg-eq/ 100 g) obtained by [34]. These recorded differences might be due to the soil quality difference used by these two studies.

The effects of PGPR on maize varied with the bacteria strains used to inoculate the plants. Maize inoculated with PGPR grew faster than the non-inoculated control. These observations were made from early in the development of the maize where by the inoculated seeds had a faster germination and a higher vigor index. At the end of the experiment plants inoculated with PGPR were taller than the non-inoculated control. The tallest plants were obtained from treatment with A. lipoferum where the plants were 37.32% taller than the control. Our results concur with those of [23], where inoculation with A. lipoferum DSM 1691 and P. fluorescens DSM 50090 produced the tallest maize plant, 21.75% and 19.93% taller than the control. In a study by [35], inoculation of mustard seeds with PGPR led to a 56.5% increase in plant height compared to the control. However the percent increase in maize circumference after inoculation of seeds with a combination of P. fluorescensand-P. putida was higher than that obtained in mustard pants using the same bacteria combination. This shows that the response to PGPR may vary with plant species.

In our research, the highest numbers of leaves were observed with seeds treated with the combination of P. fluorescens and-P. putida. This combination of bacteria also led to highest increase in leaf area [24] obtained with seeds inoculated with A. brasilense compared to the control. In different studies where pants were inoculated with Pseudomonas, Azospirillum and Azotobacter species the results were similar to those obtained in our study [36,20,37]. The positive effects of PGPR observed in our study are results of factors that have been documented in other investigations. The increase in growth triggered by seed inoculation with PGPR on crops such as maize [4], wheat [2], soy [3] and sugar beet [38] has been attributed to nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization and production of phytohormones. [39] reported that the increase of plants inoculated with PGPR was due to locally increasing of available nutrients, facilitating nutrient absorption and detoxifying heavy metals caused by PGPR. Increase in growth parameters and yield of several crops after seed inoculation with PGPR have been reported in other studies [40-42].

Maize inoculated with PGPR showed significant increase in biomass compared to the control. The highest increase of 53.72% and 108.71% for shoot and root biomass respectively was obtained in plants inoculated with a combination of P. fluorescens-P. putida [24]. The maize seeds inoculated with PGPR improved considerably the rate of plants aerial dry matter in our study. The highest aerial biomass and underground biomass were obtained with plants treated with the combination of P. fluorescens and-P. putida. By treating the maize seeds with PGPR, [24] got noticed considerable increases of the aerial fresh matter neighboring 167% and 77% respectively for A. lipoferum DSM 1691 and P. fluorescens DSM 50090. Our results demonstrated that the combinations of the PGPR P. fluorescens and P. putida gave the best aerial dry matter rates up to 59.11% of increase Also the highest underground dry matter rates have been recorded with plants treated with A. lipoferum. We can signal that several works [24] revealed light reductions of the aerial dry matter for most of the PGPR in the contrary of P. fluorescens R-93 that led an increase of 62.34 %. [17] The wheat plants inoculated with Azospirillum brasilense induced the increase of the dry weight of the root system and that of the dry weight. In greenhouse condition, it has been shown that the increase of the dry matter of radish yield was obtained after seed inoculation with Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Rhizobium leguminosarum pv. phaseoli, R. leguminosarum pv trifolii, R. leguminosarumpv. viciae and Sinorhizobium meliloti [43]. According to [45], the auxin produced by the rhizobacteria can positively influence the development of the root system, and then contributes to improve essential nutritive elements absorption for the plant growth.

5. Conclusion

This study confirms the promoter effect of PGPR on germination and the plants growth. The single inoculation of maize seeds (Zea mays L.) by the rhizobacteria A. lipoferum, P. fluorescens, P. putida and their different combinations improved considerably the maize plants in vitro germination and in the greenhouse. Among all tested PGPR treatments, the combination of P. fluorescens and P. putida gives the best efficient. The combination of rhizo-bacteria from the same species is therefore more efficient than the combination of different rhizobacteria from different species. These results suggest the possibility to use these PGPR as biologic fertilizer to increase the output of maize.

6. Acknowledgements

The authors thank the International Foundation of Science (IFS) which granted NOUMAVO Pacôme (Research grant No. C/5252-1).

REFERENCES

- S. C. Wu, Z. H. Cao, Z. G. Li, K. C. Cheung and M. H. Wong, “Effects of Biofertilizer Containing N-Fixer, P and K Solubilizers and AM Fungi on Maize Growth: A Greenhouse Trial,” Geoderma, Vol. 125, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 155-166. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.07.003

- A. Salantur, A. Ozturk and S. Akten, “Growth and Yield Response of Spring Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) to Inoculation with Rhizobacteria,” Plant, Soil and Environment, Vol. 52, No. 3, 2006, pp. 111-118.

- A. J. Cattelan, P. G. Hartel and J. J. Fuhrmann, “Screening for Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria to Promote early Soybean Growth,” Soil Science Society of America Journal, Vol. 63, No. 6, 1999, pp. 1670-1680. doi:10.2136/sssaj1999.6361670x

- D. Egamberdiyeva, “The Effect of Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria on Growth and Nutrient Uptake of Maize in Two Different Soils,” Applied Soil Ecology, Vol. 36, No. 2-3, 2007, pp. 184-189. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2007.02.005

- E. Somers, J. Vanderleyden and M. Srinivasan, “Rhizosphere Bacterial Signalling: Alove Parade beneath Our Feet,” Critical Reviews in Microbiology, Vol. No. 4, 30, 2004, pp. 205-240. doi:10.1080/10408410490468786

- F. Ahmad, I. Ahmad and M. S. Khan, “Screening of FreeLiving Rhizospheric Bacteria for Their Multiple Plant Growth Promoting Activities,” Microbiological Research, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2006, pp. 1-9.

- R. Bharathi, R. Vivekananthan, S. Harish, A. Ramanathan and R. Samiyappan, “Rhizobacteria-Based Bio-Formulations for the Management of Fruit Rot Infection in Chillies,” Crop Protection, Vol. 23, No. 6, 2004, pp. 835- 843. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2004.01.007

- Y. C. Jeun, K. S. Park, C. H. Kim, W. D. Fowler and J. W. Kloepper, “Cytological Observations of Cucumber Plants During Induced Resistance Elicited by Rhizobacteria,” Biological Control, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2004, pp. 34- 42. doi:10.1016/S1049-9644(03)00082-3

- A. Adesemoye, H. Torbert and J. Kloepper, “Plant GrowthPromoting Rhizobacteria Allow Reduced Application Rates of Chemical Fertilizers,” Microbial Ecology, Vol. 58, No. 4, 2009, pp. 921-929. doi:10.1007/s00248-009-9531-y

- H. El Zemrany, J. Cortet, M. Peter Lutz, A. Chabert, E. Baudoin, J. Haurat, N. Maughan, D. Felix, G. Défago, R. Bally and Y. Moënne-Loccoz, “Field Survival of the Phytostimulator Azospirillum lipoferum CRT1 and Functional Impact on Maize Crop, Biodegradation of Crop Residues, and Soil Faunal Indicators in a Context of Decreasing Nitrogen Fertilization,” Soil Biology and Biochemistry, Vol. 38, No. 7, 2006, pp. 1712-1726. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.11.025

- L. Fuentes-Ramirez and J. Caballero-Mellado, “Bacterial Biofertilizers,” In: Z. A Siddiqui, Ed., PGPR: Biocontrol and Biofertilization, Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Berlin, 2006, pp. 143-172. doi:10.1007/1-4020-4152-7_5

- T. J. Burr, M. N. Schroth and T. Suslow, “Increased Potato Yields by Treatment of Seed Pieces with Specific Strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens and P. putida,” Phytopathology, Vol. 68, 1978, pp. 1377-1383. doi:10.1094/Phyto-68-1377

- B. R. Glick, L. Changping, G. Sibdas and E. B. Dumbroff, “Early Development of Canola Seedlings in the Presence of the Plant GrowthPromoting Rhizobacterium Pseudomonas putida GR12-2,” Soil Biology and Biochemistry, Vol. 29, No. 8, 1997, pp. 1233-1239. doi:10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00026-6

- M. I. Frommel, J. Nowak and G. Lazarovits, “Treatment of Potato Tubers with a Growth Promoting Pseudomonas sp.: Plant Growth Responses and Bacterium Distribution in the Rhizosphere,” Plant and Soil, Vol. 150, No. 1, 1993, pp. 51-60. doi:10.1007/BF00779175

- J. R. de Freitas and J. J. Germida, “Growth Promotion of Winter Wheat by Pseudomonads fluorescentunder Growth Chamber Conditions,” Soil Biology and Biochemistry, Vol. 24, No. 11, 1992, pp. 1127-1135. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(92)90063-4

- R. O. Pedraza, C. H. Bellone, S. Carrizo de Bellone, P. M. F. Boa Sorte and KRdS Teixeira, “Azospirillum Inoculation and Nitrogen Fertilization Effect on Grain Yield and on the Diversity of Endophytic Bacteria in the Phyllosphere of Rice Rainfed Crop,” European Journal of Plant Pathology, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2009, pp. 36-43.

- S. Dobbelaere, A. Croonenborghs, A. Thys, D. Ptacek, J. Vanderleyden, P. Dutto, C. Labendera-Gonzalez, J. Caballero-Mellado, F. Aguirre, Y. Kapulnik, S. Brener, S. Burdman, D. Kadouri, S. Sarig and Y. Okon, “Response of Agronomically Important Crops to Inoculation with Azospirillum,” Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, Vol. 28, No. 9,2001, pp. 871-879. doi:10.1071/PP01074

- M. Lucy, E. Reed and B. R. Glick, “Applications of Free Living Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria,” Anton Leeuw International Journal G, Vol. 86, No. 1, 2004, pp. 1-25. doi:10.1023/B:ANTO.0000024903.10757.6e

- C. Jacoud, D. Faure, P. Wadoux and R. Bally, “Development of a Strainspecific Probe to Follow Inoculated Azospirillum lipoferum CRT1 under Field Conditions and Enhancement of Maize Root Development by Inoculation,” FEMS Microbiology Ecology, Vol. 27, No. 1, 1998, pp. 43-51. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.1998.tb00524.x

- K. Shaukat, S. Affrasayab and S. Hasnain, “Growth Responses of Helianthus annus to plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Used as a Biofertilizer,” International Journal of Agricultural Research, Vol. 1, No. 6, 2006, pp. 573-581. doi:10.3923/ijar.2006.573.581

- B. Badu-Apraku and C. G. Yallou, “Registration of StrigaResistant and Drought-Tolerant Tropical Early Maize Populations TZE-W Pop DT STR C4 and TZE-Y Pop DT STR C4,” Journal of Plant Research, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2009, pp. 86-90.

- A. Adjanohoun, L. Baba-Moussa, R. G. kakaï, M. Allagbé, B. Yèhouénou, H. Gotoechan-Hodonou, R. Sikirou, P. Sessou and D. Sohounhloué, “Caractérisation des Rhizobactéries Potentiellement Promotrices de la Croissance Végétative du Maïs dans Différents Agrosystèmes du Sud-Bénin,” International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2011, pp. 433-444. doi:10.4314/ijbcs.v5i2.72073

- M. Govindappa, V. Ravishankar, Rai and S. Lokesh, “Screening of Pseudomonas fluorescens Isolates for Biological Control of Macrophomina phaseolina Root-Rot of Safflower,” African Journal of Agricultural Research, Vol. 6, No. 29, 2011, pp. 6256-6266. doi:10.5897/AJAR10.1017

- A. Gholami, S. Shahsavani and S. Nezarat, “The Effect of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) on Germination, Seedling Growth and Yield of Maize,” World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, Vol. 49, 2009, pp. 19-24.

- J. Yadav, J. P. Verma and K. N. Tiwari, “Effect of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Seed Germination and Plant Growth Chickpea (CicerarietinumL.) under in Vitro Conditions,” Biological Forum-Annual of International Journal., Vol.2, No. 2, 2010, pp. 15-18.

- H. Boudoudou, R. Hassikou, A. OuazzaniTouhami, A. Bado and A. Douira, “Paramètres Physicochimiques et Flore Fongique des Sols de Rizières Marocaines,”Bulletin de la Société de Pharmacie de Bordeaux, Vol. 148, No. 1-4, 2009, pp. 17-44.

- R. H. Bray and L. T. Kurtz, “Determination of Total, Organic and Available Forms of Phosphorus in Soils,” Soil Science, Vol. 59, No. 2, 1945, pp. 39-45. doi:10.1097/00010694-194501000-00006

- G. W. Thomas, “Exchangeable Cations,” In: R. H. Miller and D. R. Keeney, Eds., Methods of Soil Analysis, Madison, 1982, pp. 154-157.

- A. Walkley and C. A. Black, “An Examination of the Degtjareff Method for Determining Soil Organic Matter and a Proposal Modification of the Chromic Acid Titration Method,” Soil Science, Vol. 37, No 1, 1934, pp. 29- 38. doi:10.1097/00010694-193401000-00003

- A. C. Etèka, “Comtribution des ‘Jachère’ Manioc dans l’Amelioration du Rendement des Cultures et du Prélèvement des Nutriments: Cas de la Succession Culturale Manioc-Maïs au Centre du Bénin,” Thèse de DEA, Université d’abomey-Calavi, Abomey-Calavi, 2005.

- F. Ruget, R. Bonhomme and M. Chartier, “Estimation Simple de la Surface Foliaire de Plantes de Maïs en Croissance,” Agronomie, Vol. 16, No. 9, 1996, pp. 553- 562. doi:10.1051/agro:19960903

- Z. Fatima, M. Saleemi, M. Zia, T. Sultan, M. Aslam, R. Rehman and M. FayyazChaudhary, “Antifungal Activity of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Isolates against rhizoctoniasolani in Wheat,” African Journal of Biotechnology, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2009, pp. 219-225.

- F. J. Anzala, “Contrôle de la Vitesse de Germination chez le Maïs (Zea mays) : Etude de la Voie de Biosynthèse des Acides Aminésissus de l’Aspartate et Recherche de QTLs,” Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Angers, Angers, 2006.

- A. Adjanohoun, M. Allagbé, H. Gotoechan-Hodonou, K. K. Dossa, R. Aguégué, J. Adeyemi, M. Bossou, S. Babio, L. Baba-Moussa and R. L. Glèlè-Kakaï, “Evaluation des Effets des Rhizobactéries Promotrices de la Croissance Végétative sur la Croissance du Maïs en Condition de Serre au Sud-Bénin,” Bulletin de la Recherche Agronomique du Bénin, Vol.70, 2012, pp. 60-66.

- H. Asghar, Z. Zahir, M. Arshad and A. Khaliq, “Relationship between in VitroProduction of Auxins by Rhizobacteria and Their Growth-Promoting Activities in Brassica juncea L.,” Biology Fertility of Soils, Vol. 35, No. 4, 2002, pp. 231-237. doi:10.1007/s00374-002-0462-8

- K. Shaukat, S. Affrasayab and S. Hasnain, “Growth Responses of Triticum aestivum to Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Used as a Biofertilizer,” Research Journal of Microbiology, Vol. 1, No. 4, 2006, pp. 330-338. doi:10.3923/jm.2006.330.338

- I. A. Siddiqui and S. S. Shaukat, “Mixtures of Plant Disease Suppressive Bacteria Enhance Biological Control of Multiple Tomato Pathogens,” Biology and Fertility of Soils, Vol. 36, No. 4, 2002, pp. 260-268. doi:10.1007/s00374-002-0509-x

- R. Cakmakci, F. Donmez, A. Aydin and F. Sahin, “Growth Promotion of Plants by plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria under Greenhouse and Two Different Field Soil Conditions,” Soil Biology and Biochemistry, Vol. 38, No. 6, 2006, pp. 1482-1487. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.09.019

- G. I. Burd, D. G. Dixon and B. R Glick, “Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria That Decrease Heavy Metal Toxicity in Plants,” Canadian Journal of Microbiology, Vol. 33, No. 3, 2000, pp. 237-245. doi:10.1139/w99-143

- V. Gravel, H. Antoun and R. J. Tweddell, “Growth Stimulation and Fruit Yield Improvement of Greenhouse Tomato Plants by Inoculation with Pseudomonas putida or Trichoderma atroviride: Possible Role of Indole Acetic Acid (IAA),” Soil Biology and Biochemistry, Vol. 39, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1968-1977. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.02.015

- A. A. Z. Shaharoona, Muhammad B. Arshazachir and A. Azeem Kalid, “Performance of Pseudomonas spp. Containing Accdeaminase for Improving Growth and Yield of Maize (Zea mays L.) in the Presence of Nitrogenous Fertilizer,” Soil Biology and Biochemistry, Vol. 38, No. 9, 2006, pp. 2971-2975. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.03.024

- J. Kozdroja, J. T. Trevorsb and J. D. van Elsasc, “Influence of Introduced Potential Biocontrol Agents on Maize Seedling Growth and Bacterial Community Structure in the Rhizosphere,” Soil Biology and Biochemistry, Vol. 36, No. 11, 2004, pp. 1775-1784. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.04.034

- H. Antoun and J. W. Kloepper, “Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR),” In: S. Brenner and J. H. Miller, Ed., Encyclopedia of Genetics, Academic Press, New York, 2001, pp. 1477-1480.

- H. Antoun, C. J. Beauchamp, N. Goussard, R. Chabot and R. Lalande, “Potential of Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium Species as Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Non-Legumes: Effect on Radishes (Raphanus sativus L.),” Plant and Soil, Vol. 204, No. 1, 1998, pp. 57-67. doi:10.1023/A:1004326910584

- A. Vikram, “Efficacy of Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria Isolated from Vertisols on Growth and Yield Parameters of Sorghum,” Research Journal of Microbiology, Vol. 2, No. 7, 2007, pp. 550-559. doi:10.3923/jm.2007.550.559

NOTES

*Corresponding author.