Open Journal of Medical Psychology

Vol.2 No.4(2013), Article ID:38538,10 pages DOI:10.4236/ojmp.2013.24028

Web Based Supportive Intervention for Families Living with Schizophrenia—An Open Trial

Department of Health Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Email: sigrid.stjernsward@med.lu.se

Copyright © 2013 Sigrid Stjernswärd, Lars Hansson. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received August 28, 2013; revised September 28, 2013; accepted October 5, 2013

Keywords: Families; Online Communities; Social Support; Schizophrenia

Abstract

Background: Web based modalities should be explored to support families living with mental illness. A web based tool including a psychoeducative module, a diary and a password protected forum was developed aimed at relatives’ of a person with schizophrenia to alleviate daily life. Aim: The aim of the present study was to explore participants’ use of the web based tool with focus on the forum and its potential health and psychosocial benefits. Methods: Nineteen persons participated in this explorative open trial. The forum posts were analyzed using content analysis. Self-rating instruments assessing caregiver burden, stigma and the tool’s usability were analyzed with descriptive statistics. Results: The qualitative analysis resulted in four main categories and subcategories describing relatives’ situation and interaction in the forum: Caring for a Person with Schizophrenia, Crisis and Care, Secrecy vs Openness, and Interaction and Social Support. Experiences of caregiver burden, but also fulfillment with caregiving tasks were reported. Concealing or hiding the family’s mental illness was common, but also the ability to use inner strength to cope with stigma and discrimination. The mean usability score was 59 (70 = good). Conclusion: Web based support can help address some of the families’ needs of support, although it encompasses certain limitations. Patient rights and the availability of resources, especially in cases of emergency, need to be made easily visible and accessible to alleviate families’ burden.

1. Introduction

The deinstitutionalization of psychiatric services has led to a reduction of beds and to shorter and more frequent hospital admissions. This places more responsibility on families for whom support is detrimental [1], possibly leading to added burden [2]. Caregivers’ Quality of Life (QoL) is strongly affected by physical, emotional and economic distress due to unfulfilled needs related to being a caregiver of patients with schizophrenia [3]. Restoration of patient functioning in family and social roles, lack of spare time, and economic burden are some of the factors causing the distress, which can be subjects for future interventions [3]. Boyer et al. [4] suggest interventions focusing on coping strategies, the improvement of the social network, stigma reduction and the development of personal strength to improve caregivers’ QoL.

Research shows that 40% of families living with mental illness experience such psychological distress that they require therapeutic interventions [5]. Family interventions can improve the emotional climate of the family

[6]. They can contribute to lower relapse rates and better outcomes, including reduced expressed emotion and better problem-solving capacities in families with a child with mental ill health [7,8]. Family interventions are highly prioritized in Swedish and international guidelines covering psychosocial interventions for people with schizophrenia. Several studies show that implementation in practice has been scattered and slow. New modalities, e.g. web based services, to optimize support for patients and families should be explored, in accordance with international and national e-health guidelines.

Access of transport and driving concerns [9] can be barriers to participate in psychoeducative programmes and may be overcome through web based support. Family interventions online have shown increased knowledge amongst participants, both in patients with schizophrenia and relatives [10,11]. Convenience of access [12] and 24/7 availability contribute to the growth of online communities (OC). Users value sharing experiences with similar others [13,14] and expressions of empathy [13, 15]. High levels of support have been observed in support groups for illnesses that are embarrassing, socially stigmatizing or disfiguring and for illnesses with interpersonal consequences [16]. Online systems that offer a sense of anonymity and privacy can have a disinhibitory effect on information seeking online [17]. The social contact and supporting network can reduce isolation and give new perspectives [9]. It can be a source of instrumental and emotional support, affecting mental health positively [18]. Previous studies on health forums show an exchange of informational, emotional, esteem and network support [e.g. 19], based on Cutrona and Suhr’s definitions of support [20]. Social support has a buffering and mediating role influencing physical and mental health [21,22]. Involving users in the development of information and format of sharing experiences can promote hope [13]. Such involvment shows that the experienced problems are common, reducing feelings of alienation and isolation [13,23,24]. Through online communities users can gather information, help and interact with others in a similar situation [25].

Sharing experiences online may have further beneficial effects. Exploring how living with a chronic disease affects daily life and storytelling can be empowering methods [26] that create a sense of mastery over one’s life [27]. Making sense of traumatic events can reduce ruminative thoughts related to an illness [28]. The literature shows that expressive writing has beneficial physical and mental health effects and studies have been replicated across different groups and cultures [29,30]. In the course of an earlier project a digitally based tool aimed at supporting relatives living with depression was developed using an iterative design process and close cooperation with users, showing promising results [31]. The tool was based on a theoretical framework involving the potential health benefits of expressive writing and social support in connection with stressful events. The developed tool promoted communication with the self and others, gave a sense of perspective and empowerment, and contributed to reflection and less ruminative thoughts. It offered a space to ventilate feelings, share experiences, advice and support with similar others, and contributed to reduce feelings of social isolation and alienation [24].

Within the framework of a new study the aim is to investigate the effectiveness of web based ways of supporting families living close to a person with schizophrenia. The aim of the present open trial was to investigate participants’ use of a web based tool and its potential beneficial health and psychosocial effects. Focus in the present study is on the forum, seeking to answer the following research questions: which phenomena relating to the relatives’ situation perspire in the forum? What kind of social support is exchanged in the forum and with which potential effects?

2. Ethical Considerations

The present study is part of a larger project, which was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee in Lund, Sweden (Dnr 2012/565).

3. Methods@NolistTemp#3.1. Design

An explorative design was chosen for the present open trial, including a qualitative approach to assess the forum’s value and a quantitative approach encompassing the use of self-rating questionnaires to assess participants’ experiences of burden, stigma and discrimination, and the tool’s usability.

3.2. Intervention

The intervention consists of a web based tool with three modules aimed at relatives/significant others of a person with schizophrenia: a psychoeducative module with information on mental illness, treatment and the role of the family; a private diary, facilitating expressive writing; and a moderated and members only forum, facilitating social support. A user peer group including patients and relatives reviewed the psychoeducative module’s contents, a novelty compared to the initial project. Access to the full website required registration, the use of an alias and password to protect anonymity and users’ integrity. The moderator occasionally posted questions in the forum to spur discussions, e.g. exploring participants’ experiences and needs of support. The test period’s length was (16) weeks, between (February and May 2013). Participants were asked to use the diary and forum weekly to ensure a certain level of activity.

3.3. Sample

Participants were recruited through advertisement in two regional newspapers, on support organizations’ websites, bulletin boards in public places (e.g. libraries and hospital wards in 3 cities in southern Sweden) and through social media. Inclusion criteria were being a relative or significant other of a person with schizophrenia, aged 18 - 80, having access to a computer and Internet connection, understanding and writing Swedish. Participants enrolled by sending an informed consent to the research team. Information about the study was made available online and through e-mail on request. Nineteen persons enrolled by sending an informed consent and registering onto the website. The sample included 6 men and 13 women, aged 26 to 74 (mean age = 53).

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

In connection to their registration to the website, participants were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire (see Table 1) and a number of self-rating instruments online: CarerQoL7-D [32] measures 7 dimensions (fulfillment, relational dimension, mental health dimension, social dimension, financial dimension, perceived support, and physical dimension) of caregiver burden. It consists of CarerQoL-7D and CarerQol-VAS. The latter indicates the level of happiness with caregiver’s experiences, encompassing both negative and positive aspects, ranging from 0 = “completely unhappy” to 10 = “completely happy”. Nine items from DISC-12 [33] of relevance for caregivers were included. DISC-12 [34] measures different aspects of stigma and discrimination related to mental illness. Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot) and 4 (not applicable). The 9 items were chosen from three of the four original subscales: 1) Unfair treatment (6 items); 2) Stopping self (2 items); 3) Overcoming stigma (1 item). After the test period, participants answered a Swedish version [35] of the system usability scale (SUS) [36], but only 10 (52.5%) participants answered the scale. It consists of 10 questions (possible values 0 - 4) and the total value can be 0 - 100. Values over 70 can be estimated as good and >85 as excellent, although acceptability in the field cannot be guaranteed [37]. Quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive statistics in IBM-SPSS21.

Qualitative data was analyzed using content analysis [38]. Data consisted of forum posts (n = 34) amounting to ap-

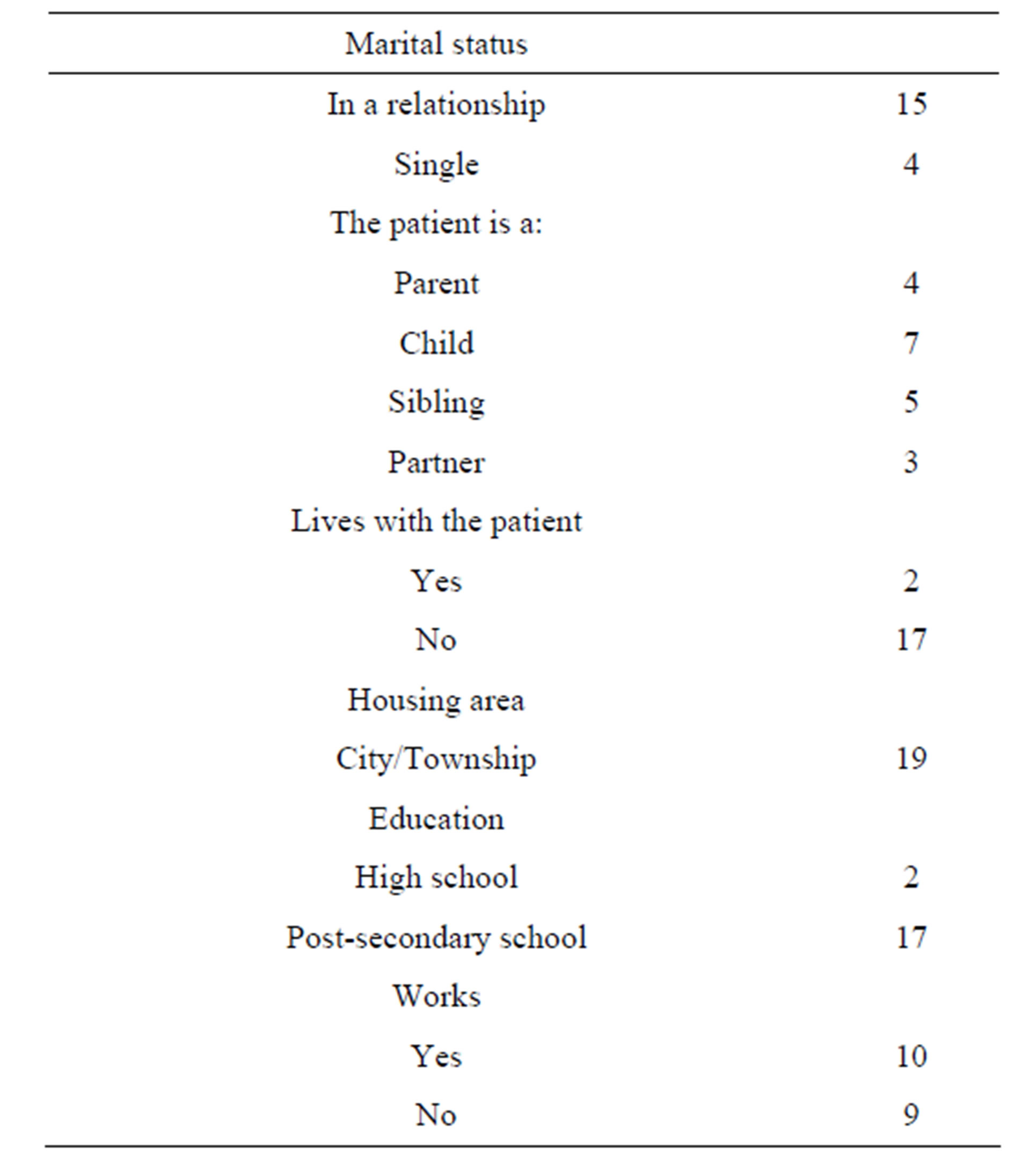

Table 1. Background information.

proximately 14 printed pages. Seven participants wrote in the forum, with a range of 2 - 8 posts/comments per participant. The printouts were read several times to reach an understanding of the whole. Contents relating to the research questions were marked and coded, then grouped and abstracted into categories and subcategories. Comparisons across categories were made to identify similarities and differences. The transcripts were reread to assess the emerging coding scheme’s fit with the material. Frequencies of diverse types of social support based on Cutrona and Suhr’s [20] definition were also noted. An independent researcher (second author) analyzed data to assess the coding scheme’s and the results’ reliability.

4. Schizophrenia Results

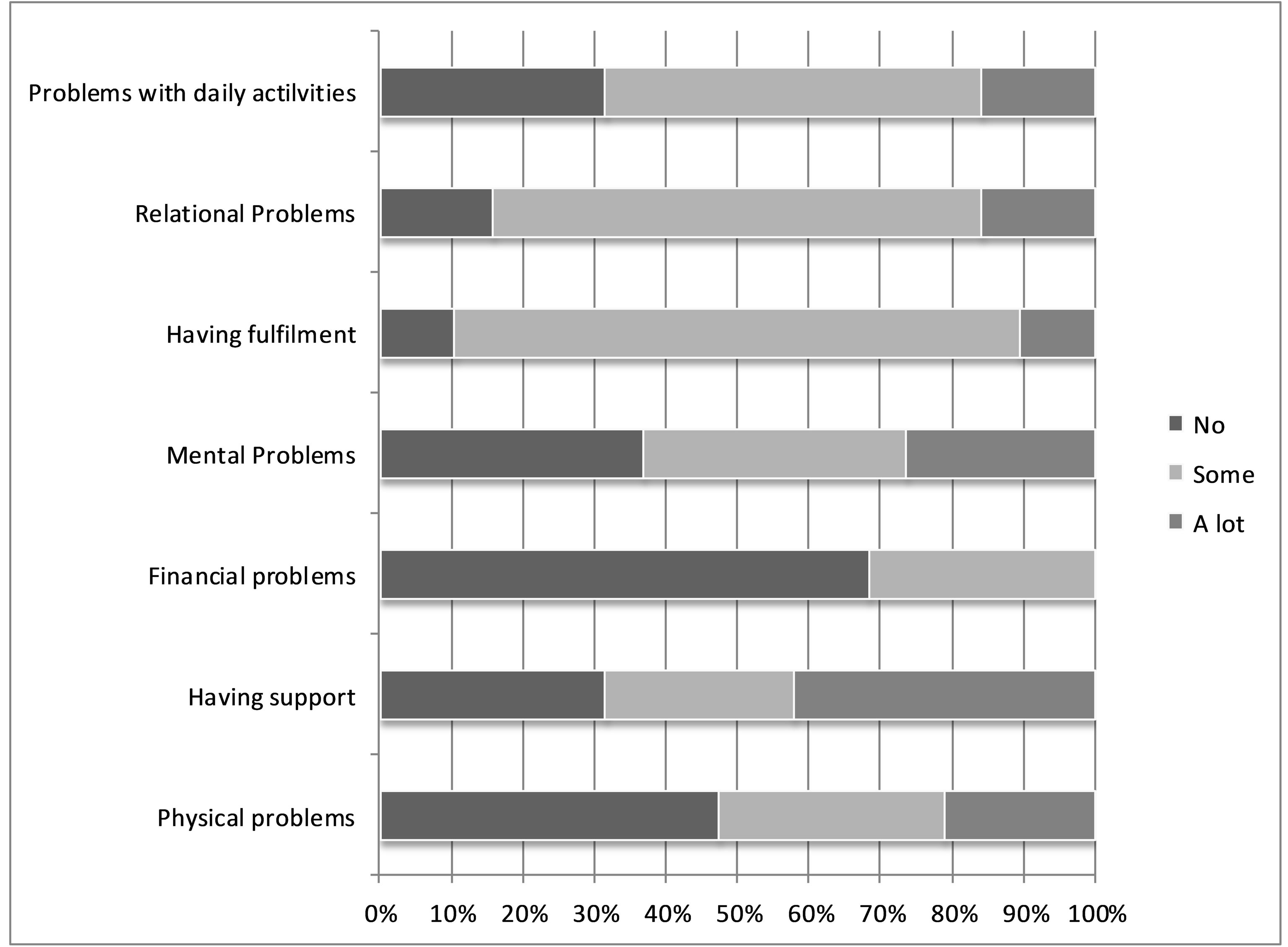

Experiences of caregiver burden and of stigma and discrimination were reported through Carer QoL7-D (see Figure 1) and DISC-12 items (see Table 2). CarerQoLVAS, a summary measure of the subjective burden, had a mean score of 6.78 (range = 2 - 10).

Most participants (89.5%) felt some to a lot of fulfillment from their care tasks and over two third (68.5%) reported some to a lot of problems in combining care tasks with daily activities. Approximately a third reported that they did not receive support in their caregiver role. Sixty three percent reported some to a lot of problems with their own mental health and over half reported having some to a lot of physical problems. Most participants (84%) reported relational problems with the care recipient.

Through DISC-12, 79% of all participants reported having concealed or hidden the patient’s condition from others, but most (84%) also reported that they had been able to use their inner strength to cope with stigma and discrimination to varying extents. A third of all participants reported different levels of unfair treatment from their partner and family, and a fifth reported that they had stopped themselves from having a close personal relationship. Approximately a fifth had experienced unfair treatment by mental health staff; however most had not experienced unfair treatment by the police or in keeping a job.

The analysis of the forum posts resulted in a number of categories and subcategories describing areas of concern for the participants’ and their interaction in the forum: Caring for a Person with Schizophrenia, Crisis and Care, Secrecy vs Openness, and Interaction and Social Support.

4.1. Caring for a Person with Schizophrenia@NolistTemp#4.1.1. The Patients’ Situation

The reason for participating in the forum is being a relative or significant other of a person with schizophrenia.

Figure 1. Problems/circumstances linked to the care giving situation as reported in CarerQoL-7D.

Table 2. Experienced and anticipated discrimination.

The starting point is thus the patient and his/her situation, which participants describe in more or less detail, including the type of relationship to the patient, the patient’s living situation, pharmacological and other treatment, and problems in daily life. The latter also include participants’ interaction with the patient and other family members, their handling of patients’ needs for care and support, and worries about the future.

4.1.2. Relating to the Patient

Relating to and caring for a person with schizophrenia appears challenging in different ways. It triggers numerous questions about the patient’s care. A strong wish and need for more knowledge is expressed through multiple queries in the forum. Subjects range from altered relationships to treatment alternatives, the health care system, the handling of emergencies and day to day problems in the patient’s life. Some relatives describe a grieveing change of personality in the patient and struggles in coming to terms with it. Participants describe challenges related to their relationship with and behavior towards the patient, not the least with regards to the patient’s limited energy and capacity to handle daily life and his/her own care. Participants express feelings of frustration towards this and the experienced lack of support from the social services. The relatives’ subsequent need to support the patient, e.g. through cleaning and establishing or upholding contact with health professionals, can eventually affect their own health and well-being and prompt feelings of despair. Several participants express worries about the patient’s future life situation and his/her ability to cope without the relatives’ help.

4.1.3. Own Support

When prompted by the moderator about own needs and proposals of support, many participants describe that they were not offered specific support, either as children or grown-ups. Many felt lonely and sometimes confused about the situation. Some participants eventually sought own professional help. Interestingly, more than own support many participants describe the support offered or not to the patient, which appears partly insufficient.

4.2. Crisis and Care@NolistTemp#4.2.1. Health and Emergency Care

Who to contact for support and care, especially in cases of emergency, and how relatives are received and treated by health professionals seem like significant sources of worry and frustration. Relatives often become an intermediary between the patient and diverse organizations, whether in emergency situations or regarding daily needs of care and support. Participants describe both positive and negative experiences of care and how they were treated as relatives.

Many participants describe great frustration with the health care system. Not being believed, heard or taken seriously and being referred to other instances in cases of emergency are described as taxing experiences. Difficulties emerge when patients don’t ask for help themselves and lack insight. Not knowing whom to ask for help appears most stressful. Several participants describe that it takes a crisis to get help. This entails an extreme state and sometimes dramatic interventions including police involvement. It leads to a worsening of the patient’s health, takes a toll on relatives’ strength and creates worries about future care. Participants would like to see contact persons/teams that can be reached for help around the clock to prevent such deterioration. Positive experiences are also described such as contact with attentive health professionals. The latter are sought for, especially in emergency situations when many participants appear to feel lonesome and desperate for help. Knowing that the patient has support, e.g. within supported housing, can alleviate relatives’ burden and apprehensions about handling approaching psychoses. Nevertheless, experienced lacks of support within the patients’ housing facilities come out as a source of frustration and concerns in several participants’ accounts.

4.2.2. Social Care

From the participants’ accounts it appears that a number of patients live with supported housing. Participants describe a frustration with the patients’ living situation and unaddressed needs of e.g. cleaning. They experience that the staff’s in supported housing facilities by regulations limited role in supporting patients doesn’t cover patients’ true needs. The relatives feel a responsibility to help and compensate for this situation, either by practically supporting the patient and/or and by advocating for the patient’s needs to obtain more adequate help through the responsible organizations. It requires substantial knowledge and efforts, which in the long run seems to affect relatives’ own health and well-being. Knowing that there are dedicated personnel is thus a relief, as described by a few participants, although some describe a disconcerting and saddening institutionalization process that alters the patient’s personality.

4.2.3. Secrecy vs Openness

Lack of knowledge, stigma and self-stigma emerge as important issues for relatives to deal with. The public lack of knowledge regarding schizophrenia and subsequent attitudes are described as distressing. Thoughtless and unenlightened comments hurt and spur a wish to spread accurate knowledge in society. Worries about people’s reactions lead the relatives to conceal the patient’s illness. Secrecy around the patient’s diagnosis can sometimes be experienced as tricky and isolating. Participants describe both supportive and thoughtless reactions from their social network. When offered they appreciate their network’s support, but also realize that others’ understanding and potential support can only be limited. Participants don’t expect others to fully understand their circumstances, nor blame them for it.

4.3. Interaction and Social Support

The analysis of participants’ interaction in the forum shows that they through their descriptive accounts, enquiries and responses exchange diverse types of social support, including informational, emotional and esteem support. Participants express a desire and need for knowledge, both in the public and themselves. Subjects of enquiry are for instance related to the patients’ treatment and sources of care and support. Nevertheless, some posts did not receive any response, leaving their sender without further clues or support.

4.3.1. Informational, Emotional and Esteem Support

The most frequently exchanged support is informational, followed by emotional and ultimately esteem support. Participants exchange informational support in form of advice or referrals relating to the patients’ pharmacological and psychological treatment, the handling of crises and of patients’ unmet needs of support (e.g. cleaning), and regarding relatives’ own needs of support (e.g. tips about support organizations). Emotional and esteem support are also exchanged. Participants express sympathy and understanding towards each other’s situation. They sometimes express recognition of and validate each other’s experiences. Participants attempt to convey hope through encouragements. Single participants wish for face-to-face contact with other participants, suggesting that they meet in real life, possibly enlarging their social network and thereby providing network support.

4.3.2. Empowerment and Limitations

It seems that the exchange of social support can engender feelings of empowerment. For instance it conveys help to deal with contacts with health professionals and support organizations. Knowing who to ask and what to ask for helps to handle patients’ and own needs of support. Limitations with the online format are also illuminated. Wishes to meet face-to-face with other relatives, rather than write in the forum are expressed. Some posts and questions are left unaddressed, leaving their senders without response or feedback. The number of participants was limited, which can partly explain the relatively low activity level in the forum.

4.4. Usability

Participants’ subjective assessment of the tool’s usability was calculated using the system usability scale, resulting in a mean of 59 (range 30 - 90). Most posts were written during week days (85%) as compared to weekends (15%), and between 8 am - 4 pm (56%) and 4 pm - 12 am (44%).

5. Discussion

Although 68.5% reported problems in combining care tasks with daily activities, the majority of all participants experienced fulfillment from caregiving, which is comparable to previous research [39]. However, approximately a third reported that they did not receive support in their caregiver role, corroborating Flyckt et al.’s [39] findings and previous research showing that support for families is detrimental (1). Over two third reported problems with their own mental health and over half reported physical problems, pointing to own needs of support. As reported by Coyne et al. [5], up to 40% of families living with mental illness experience mental health problems of their own that require therapeutic interventions. Most participants reported relational problems with the care recipient as compared to Flyckt et al.’s [39] 50%. Interpersonal consequences were also seen in the present stigma and discrimination reports, where a third reported experiences of unfair treatment from their partner and family, and a fifth had stopped themselves from having a close personal relationship. As previously mentioned, restoration of patient functioning in family and social roles are known factors causing distress, which can be subjects for further interventions [3].

Not all participants wrote in the forum and nothing can be said about potential lurkers. Observations of online communities indicate that lurkers represent 80% - 90% of an OC’s population [40,41]. Nonnecke and Preece [41] identify and summarize why lurkers lurk, e.g. because they first want to learn about the group, feel uncomfortable in public, worry about communication overload or don’t find it necessary to post. Poor message quality and lack of time can be further reasons [41]. As in many forums, some participants are more active than others, possibly indicating that participation in online forums works better for some individuals than others. The mean usability score (59) shows that enhancements are necessary to improve usability. Nevertheless, those participating actively seem to draw potential benefits from their involvement in diverse ways. Different areas of concern as caregivers could also be distinguished throughout the posts.

Participants’ wish for enhanced knowledge of the patient’s condition, treatment alternatives and sources of support is evident. Many participants express overwhelming feelings of frustration and loneliness in dealing with sometimes dramatic emergency situations. A wish for around the clock availability of contact persons and emergency teams is expressed to avoid deterioration of the patient’s health and subsequent negative effects on relatives’ own wellbeing. Negative symptoms appear troublesome for caregivers, concurring with previous research showing that negative symptoms are associated with objective burden, especially when responsibility attribution for negative symptoms in patients is low [42]. The ensuing lack of initiative and energy diminishes the patient’s capacity to cater for daily needs and affects the relationship to relatives. The latter feel responsible to help the patient, which in the long run may affect their health negatively unless additional support and relief can be offered. So does worrying about relapse and potential psychotic episodes. This is concurrent with previous research showing that caregivers suffer from fear, distress and confusion related to the patient’s erratic and sometimes aggressive behavior and the emotional and physical burden of care [43,44].

Participants worry about the patient’s future situation, corroborating previous research [44] and further confirming the need for caregivers’ to be unburdened. Dealing with daily support problems and recurring negotiations with the health system is burdensome, confirming that the health care system can be a source of stress [45]. Patient rights and the administrative landscape can be difficult to navigate. Reflecting upon what more can be done to alleviate families’ burden is thus a legitimate question. As of this day in Swedish mental health care, the county councils and the local municipalities have a shared responsibility to cater for patients’ and families’ needs of care and support. While some resources must be made available by law, others are optional for the municipalities to supply, possibly creating unequal distribution of care and a fragmented range of services for patients and their families. Obviously information about patient rights and available resources must be made more visible and easily accessible to facilitate support. Web based resources may be a valuable and complementary venue.

Participants’ forum interaction reveals an exchange of informational, emotional, esteem and network support [20], with informational support being the most frequently exchanged, which is concurrent with other studies [e.g. 46], possibly addressing certain needs, thereby empowering participants and conveying hope. Benzein and Berg [47], for instance, highlight the value of hopefostering strategies in meeting families. Stigma and secrecy can be isolating. Most participants in the present study reported having concealed or hidden the patient’s condition from others, but most also reported that they had been able to use their inner strength to cope with stigma and discrimination to varying extents. Guilt associated with heredity and with not having recognized symptoms earlier [44,48] can enhance caregivers’ burden. As seen in previous research [9] meeting similar others may help decrease feelings of alienation and isolation, not the least in connection with stigmatizing conditions and illnesses with interpersonal consequences [16]. Temporary sources of social support through support groups, which health professionals can recommend, may compensate for lacks of social support [49]. Sharing experiences, knowledge and support are known coping mechanisms [25] that may be empowering. The social contact can also give new perspectives on the situation [9], opening up for new solutions to old and new problems. Patients frequently perceive discrimination from mental health care staff as shown by a study on discrimination in people with mental illness [50]. In the present study, approximately a fifth had experienced unfair treatment by mental health staff.

The present study also sheds light onto limitations with the online format. Some participants express a wish and preference for face-to-face contact, entailing physical cues. The online communication can be viewed as an initiator for contact in real life, potentially filling a previous gap in the social network and experienced support. The low activity in the forum is a limitation that can be partly explained by the limited number of participants. Some posts were left unanswered, leaving their senders without feedback. It would be of interest to explore whether this has negative consequences, e.g. feelings of exposure or alienation. A wish for feedback from health professionals was found in a parallel study of a forum for families living with depression (unpublished). Although such wishes weren’t expressed directly in the present study, such feedback may enhance the forum’s value for caregivers of persons with schizophrenia too. Feedback on the present web based tool can be processed and integrated into future versions to better address participants’ needs, enhancing the tool’s usability and possibly preventing further ill health and additional costs to society. It goes in line with the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs’ statement of interest in the needs and requirements of involved parties to ensure the usefulness of health information for its users [51].

6. Limitations

The number of participants was limited, not the least the number of persons actively writing in the forum, narrowing the forum’s activity level. The moderator introduced questions to spur discussions, which may have affected subjects of discussion. Nevertheless some of the introduced threads were left unrequited, which may indicate that the answered posts nonetheless were of central interest to the participants. The use of a facilitator to encourage discussion is not uncommon as seen in other studies [52]. A facilitator that is also an expert can respond participants if no one else does or remove incorrect or potentially harmful medical information as seen in Shaw et al.’s study [53]. Although scarce in patient support groups (17), flaming can occur and should be handled, supporting the presence of a moderator. Griffiths et al. [54] suggest further studies to explore factors influencing acceptability of and satisfaction with Internet support groups (ISG), including group size, moderation, board rules, accessibility and naturalistic comparative studies of groups differing in these regards [54]. The present study shows that further studies are needed to explore the moderator’s role, optimal levels of activity and the value of professional feedback in online communities to optimize online support for families living with mental illness.

7. Conclusion

The subjects of discussion and the exchange of social support in the present forum illuminate participants’ wish for more knowledge and needs of support in caring for patients, not the least in emergency situations. This knowledge should be fed back to health professionals and politicians to optimize support to patients and families. The web based format appears to contribute to an exchange of social support, whether informational, emotional, esteem or network support, partially addressing relatives’ needs. Reduced feelings of isolation and alienation may contribute to reduce stigma and empower participants. Nevertheless limitations, such as usability and the limited forum activity, as well as preferences for face-to-face contact, were seen. Furthermore, some posts were left unanswered, raising questions about their sender’s experiences of and reactions to this. Moderated forums including occasional input with professional feedback may compensate for this lack and contribute to further support families living with mental illness, alleviating their burden and preventing further stress related ill health. Further studies are needed to explore optimal ways of supporting patients and their families.

[1] References

[2] D. D. Leo and K. Spathonis, “Do Psychosocial and Pharmacological Interventions Reduce Suicide in Schizophrenia and Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders?” Archives of Suicide Research, Vol. 7, No. 4, 2003, pp. 353- 374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713848945

[3] M. Östman and K. Andersson, “Family Burden, Participation in Care and Mental Health—An 11-Year Comparison of the Situation of Relatives to Compulsorily and Voluntarily Admitted Patients,” The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2000, pp. 191- 200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002076400004600305

[4] A. Caqueo-Urízar, J. Gutiérrez-Maldonado and C. Miranda-Castillo, “Quality of Life in Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Literature Review,” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, Vol. 7, 2009, p. 84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-84 PMid:19747384 PMCid:PMC2749816

[5] L. Boyer, A. Caqueo-Urízar, R. Richieri, C. Lancon, J. Gutiérrez-Maldonado and P. Auquier, “Quality of Life among Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Chilean and French Families,” BMC Family Practice, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2012, p. 42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-13-42 PMid:22640267 PMCid:PMC3464874

[6] J. C. Coyne, R. C. Kessler, M. Tal, J. Turnbull, C. B. Wortman and J. F. Greden, “Living with a Depressed Person,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 55, No. 3, 1987, pp. 347-352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.55.3.347

[7] F. Pharoah, J. Mari, J. Rathbone and W. Wong, “Family Intervention for Schizophrenia,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Vol. 12, 2010.

[8] L. Dixon, W. R. McFarlane, H. Lefley, A. Lucksted, M. Cohen and I. Falloon, et al., “Evidence-Based Practices for Services to Families of People with Psychiatric Disabilities,” Psychiatric Services, Vol. 52, No. 7, 2001, pp. 903-910. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903

[9] G. Thornicroft and E. Susser, “Evidence-Based PsychoTherapeutic Interventions in the Community Care of Schizophrenia,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 178, No. 1, 2001, pp. 2-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.178.1.2 PMid:11136201

[10] J. Reid, C. Lloyd and L. De Groot, “The Psychoeducation Needs of Parents Who Have an Adult Son or Daughter with a Mental Illness,” Advances in Mental Health, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2005, pp. 65-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.5172/jamh.4.2.65

[11] A. Rotondi, C. Anderson, G. Haas, S. Eack, M. Spring, R. Ganguli, et al., “Web-Based Psychoeducational Intervention for Persons with Schizophrenia and Their Supporters: One-Year Outcomes,” Psychiatric Services, Vol. 61, No. 11, 2010, pp. 1099-1105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.61.11.1099

[12] S. M. Glynn, E. T. Randolph, T. Garrick and A. Lui, “A Proof of Concept Trial of an Online Psychoeducational Program for Relatives of both Veterans and Civilians Living with Schizophrenia,” Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2010, pp. 278-287. http://dx.doi.org/10.2975/33.4.2010.278.287

[13] S. R. Cotten and S. S. Gupta, “Characteristics of Online and Offline Health Information Seekers and Factors That Discriminate between Them,” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 59, No. 9, 2004, pp. 1795-1806. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.020

[14] J. Powell and A. Clarke, “Information in Mental Health: Qualitative Study of Mental Health Service Users,” Health Expectations, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2006, pp. 359-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00403.x

[15] L. J. Barney, K. M. Griffiths and M. A. Banfield, “Explicit and Implicit Information Needs of People with Depression: A Qualitative Investigation of Problems Reported on an Online Depression Support Forum, “ BMC Psychiatry, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2011, p. 88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-88

[16] J. Preece, “Empathic Communities: Balancing Emotional and Factual Communication,” Interacting with Computers, Vol. 12, No. 1, 1999, pp. 63-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0953-5438(98)00056-3

[17] K. P. Davison, J. W. Pennebaker and S. S. Dickerson, “Who Talks? The Social Psychology of Illness Support Groups,” American Psychologist, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2000, pp. 205-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.2.205

[18] A. N. Joinson, “Understanding the Psychology of Internet Behaviour. Virtual Worlds, Real Lives,” Palgrave MacMillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, New York, 2003.

[19] R. Fuhrer, S. A. Stansfeld, J. Chemali and M. J. Shipley, “Gender, Social Relations and Mental Health: Prospective Findings from an Occupational Cohort (Whitehall II study),” Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 48, No. 1, 1999, pp. 77-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00290-1

[20] K. Y. Chuang and C. C. Yang, “Interaction Patterns of Nurturant Support Exchanged in Online Health Social Networking,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2012, p. e54.

[21] C. E. Cutrona and J. A. Suhr, “Controllability of Stressful Events and Satisfaction with Spouse Support Behaviors,” Communication Research, Vol. 19, No. 2, 1992, pp. 154- 174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/009365092019002002

[22] I. Skärsäter, “The Importance of Social Support for Men and Women, Suffering from Major Depression. A Comparative and Explorative Study,” Sahlgrenska Academy, Division of Health and Caring Sciences, Institute of Nursing, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, 2002.

[23] T. Takizawa, T. Kondo, S. Sakihara, M. Ariizumi, N. Watanabe and H. Oyama, “Stress Buffering Effects of Social Support on Depressive Symptoms in Middle Age: Reciprocity and Community Mental Health,” Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, Vol. 60, No. 6, 2006, pp. 652-661.

[24] G. J. Meissen, D. F. Gleason and M. G. Embree, “An Assessment of the Needs of Mutual-Help Groups,” American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 19, No. 3, 1991, pp. 427-442.

[25] S. Stjernswärd and M. Östman, “Illuminating User Experience of a Website for the Relatives of Persons with Depression,” International Journal of Social Psychiatry, Vol. 57, No. 4, 2011, p. 375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0020764009358388

[26] U. Josefsson, “Coping with Illness Online: The Case of Patients’ Online Communities,” The Information Society, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2005, pp. 143-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01972240590925357

[27] C. Feste and R. M. Anderson, “Empowerment: From Philosophy to Practice,” Patient Education and Counseling, Vol. 26, No. 1-3, 1995, pp. 139-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0738-3991(95)00730-N

[28] J. Rappaport, “Terms of Empowerment/Exemplars of Prevention: Toward a Theory for Community Psychology,” American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1987, pp. 121-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00919275

[29] B. R. Shaw, R. Hawkins, F. McTavish, S. Pingree and D. H. Gustafson, “Effects of Insightful Disclosure within Computer Mediated Support Groups on Women with Breast Cancer,” Health Communication, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2006, pp. 133-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1902_5

[30] J. Smyth, “Written Emotional Expression: Effect Sizes, Outcome Types, and Moderating Variables,” Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, Vol. 66, No. 1, 1998, pp. 174-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.174

[31] J. W. Pennebaker and J. D. Seagal, “Forming a Story: The Health Benefits of Narrative,” Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 55, No. 10, 1999, pp. 1243-1254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1243::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-N

[32] S. Stjernswärd, M. Östman and J. Löwgren, “Online Self—Help Tools for the Relatives of Persons with Depression—A Feasibility Study,” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2012, pp. 70-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00905.x

[33] W. B. F. Brouwer, N. J. A. V. Exel, B. V. Gorp and W. K. Redekop, “The CarerQol Instrument: A New Instrument to Measure Care-Related Quality of Life of Informal Caregivers for Use in Economic Evaluations,” Quality of Life Research, Vol. 15, No. 6, 2006, pp. 1005-1021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-005-5994-6

[34] The INDIGO Study Group, “Discrimination and Stigma Scale DISC 12©,” 2008.

[35] E. Brohan, D. Rose, S. Clement, E. Corker, T. Van Bortel, N. Sartorius, et al., “Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC), Version 12. Manual Version 3,” HSPRD Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, 2012.

[36] A. Piatidis, “Användbarhetsstämpel på Konsument-Produkter. Ett sätt att Underlätta Kundernas köp och Påverka Företagets Arbetssätt,” TRITA-NA-E02001, CID-187, 2002.

[37] J. Brooke, “SUS—A Quick and Dirty Usability Scale,” In P. W. Jordan, B. Thomas, B. A. Weerdmeester, A. L. McClelland, Eds., Usability Evaluation in Industry, Taylor and Francis, London, 1996.

[38] A. Bangor, P. Kortum and J. Miller, “An Empirical Evaluation of the System Usability Scale,” International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, Vol. 24, No. 6, 2008, pp. 574-594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10447310802205776

[39] U. H. Graneheim and B. Lundman, “Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness,” Nurse Education Today, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2004, pp. 105-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

[40] L. Flyckt, A. Löthman, L. Jörgensen, A. Rylander and T. Koernig, “Burden of Informal Care Giving to Patients with Psychoses: A Descriptive and Methodological Study,” International Journal of Social Psychiatry, Vol. 59, No. 2, 2013, pp. 137-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0020764011427239

[41] T. Connolly and B. K. Thorn, “Discretionary Databases: Theory, Data, and Implications,” Organizations and Communication Technology, 1990, pp. 219-233.

[42] B. Nonnecke and J. Preece, “Why lurkers lurk,” Americas Conference on Information Systems, 2001.

[43] H. L. Provencher, K. T. Mueser, “Positive and Negative Symptom Behaviors and Caregiver Burden in the Relatives of Persons with Schizophrenia,” Schizophrenia Research, Vol. 26, No. 1, 1997, pp. 71-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(97)00043-1

[44] J. Addington, E. Coldham, B. Jones, T. Ko and D. Addington, “The First Episode of Psychosis: The Experience of Relatives,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, Vol. 108, No. 4, 2003, pp. 285-289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00153.x

[45] S. Barker, T. Lavender and N. Morant, “Client and Family Narratives on Schizophrenia,” Journal of Mental Health, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2001, pp. 199-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638230123705

[46] L. E. Rose, “Families of Psychiatric Patients: A Critical Review and Future Research Directions,” Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, Vol. 10, No. 2, 1996, pp. 67-76.

[47] C. K. Coursaris and M. Liu, “An Analysis of Social Support Exchanges in Online HIV/AIDS Self-Help Groups,” Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 25, No. 4, 2009, pp. 911-918. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.03.006

[48] E. G. Benzein and A. C. Berg, “The Level of and Relation between Hope, Hopelessness and Fatigue in Patients and Family Members in Palliative Care,” Palliative Medicine, Vol. 19, 2005, pp. 234-240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0269216305pm1003oa

[49] M. Sanbrook and A. Harris, “Origins of Early Intervention in First-Episode Psychosis,” Australasian Psychiatry, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2003, pp. 215-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1039-8562.2003.00556.x

[50] R. H. Moos, “Depressed Outpatients’ Life Contexts, Amount of Treatment, and Treatment Outcome,” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol. 178, No. 2, 1990, pp. 105-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199002000-00005

[51] L. Hansson, S. Stjernswärd and B. Svensson, “Perceived and Anticipated Discrimination in People with Mental Illness—An Interview Study,” Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 2013, pp. 1-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2013.775339

[52] Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, “Nationell IT-Strategi för vård och omsorg. Var stårviidag?” Lägesrapport, 2007.

[53] H. Bragadottir, “Computer-Mediated Support Group Intervention for Parents,” Journal of Nursing Scholarship, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2008, pp. 32-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00203.x

[54] B. R. Shaw, F. McTavish, R. Hawkins, D. H. Gustafson and S. Pingree, “Experiences of Women with Breast Cancer: Exchanging Social Support over the CHESS Computer Network,” Journal of Health Communication, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2000, pp. 135-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/108107300406866

[55] K. M. Griffiths, A. L. Calear and M. Banfield, “Systematic Review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and Depression (1): Do ISGs Reduce Depressive Symptoms?” Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2009.