Open Journal of Psychiatry

Vol.3 No.2(2013), Article ID:30036,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojpsych.2013.32024

Coping strategies used by suicide attempters and comparison groups

![]()

1Department of Care Science Malmö, Faculty for Health and Society, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

2Department of Clinical Sciences, Psychiatry, Lund University Hospital, Lund, Sweden

Email: charlotta.sunnqvist@mah.se

Copyright © 2013 Charlotta Sunnqvist et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 15 February 2013; revised 17 March 2013; accepted 26 March 2013

Keywords: Suicide-Attempt; Stressful Situations; COPE; Adaptive and Maladaptive Coping Strategies

ABSTRACT

A variety of factors have been identified as being risk factors for suicidal behaviour. One of them is the handling of stressful events. The aim of the present study was to investigate the coping-strategies used by suicide attempters and comparison groups. 37 patients who had recently made a suicide attempt, 38 suicide attempters at follow up, 20 psychiatric follow up controls, and 19 healthy controls filled in the COPE. We found that suicide attempters at long term follow up and healthy controls used more adaptive problem solving strategies than patients who had recently made a suicide attempt, or psychiatric controls at follow up, who used more maladaptive coping strategies. Our findings suggest that suicide attempters in a twelve year follow up are able to use coping strategies similarly to healthy controls by e.g. approaching the stressor actively. Further examinations of the impact of long term professional care and treatment of suicide attempters on their coping strategies are necessary.

1. INTRODUCTION

A variety of factors have been identified as being risk factors for suicidal behaviour. One of them is the way a person dealing with stressful situations. It is not the stressful situation alone that leads to a serious outcome, but rather the way in which the person copes with it.

Coping is defined as the “cognitive and behavioural efforts used to master, tolerate, and reduce demands that tax or exceed a person’s resources” [1]. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of different coping styles in managing various kinds of stressors [2-4]. A multidimensional coping inventory, called COPE, was constructed by Carver et al. [5] to assess adaptive or maladaptive coping strategies [5,6].

Dieserud et al. [4] presented results which support a theory of two paths to a suicide attempt. Both paths include vulnerability factors such as low self-esteem, low self-efficacy, loneliness and separation/divorce. One path is suggested to comprise factors related to depression and hopelessness, while the other one includes a negative appraisal of one’s own problem solving capacity. Sunnqvist et al. [7] elucidated the pathways to suicidal behaviour using a time-geographic life charting combined with a survey of a person’s coping capacities. They found three different pathways’. The first pathway where predominantly adaptive coping capacity was used, the second where both adaptive and maladaptive coping were used, and the third where mainly maladaptive coping capacities were used. Apart from capacities to cope with stressful life events, the potential pathways illustrate a suicidal person’s social capability, predisposing life events, precipitating life events, and illness course, which all offer an extensive picture and knowledge about the suicidal individual.

Suicidal behaviour has been associated with the use of maladaptive coping strategies [8-11] and adaptive coping strategies may serve as protected factors [12-13].

Few studies have investigated whether coping strategies are persistent, or if and how they develop over the time. This is a first step to better understand the coping strategies reported by suicide attempters in an acute or a long term follow up situation, in relation to strategies reported by comparison groups. Our hypothesis was that suicide attempters in general would use weaker coping strategies than others.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

Recruitment procedures

Suicide attempters at long term follow up

The suicide attempters at follow up were originally inpatients recruited shortly after a suicide attempt (i.e. index, 1986-1992). About 12 years later, they were followed up. Before the research appointment, 84 recruitment letters were sent out, asking for participation. Later, a research nurse made a phone call, asked for consent, and offered an appointment for a research investigation. The follow up study started in 1999 and lasted until 2002. Forty-two persons participated, and 38 of them filled in the COPE (19 males and 19 females). Forty-two refrained from participating in the follow up.

Psychiatric controls who had not attempted suicide

The psychiatric controls at follow up were recruited among those who were inpatients during the same time period (index) as the suicide attempters. They had no history of suicide attempt prior to that time. These controls were matched to the followed up suicide attempters according to their principal DSM III-R diagnosis [14] at the time of index hospitalisation, as well as to their gender and age (±5 years, with one exception of ±8 years). Twenty psychiatric follow up controls filled in the COPE (7 males and 13 females) and their mean ± SD age was 49.9 ± 8.9. The charts of 270 cases were reviewed, 71 were contacted and 23 participated. One of these 23 was excluded because of a suicide attempt that was detected before hospitalization.

Recent suicide attempters

From the emergency room, the medical intensive care unit, or from a general psychiatric ward at the University Hospital of Lund, Sweden, 37 patients (16 males and 21 females) were recruited shortly after a suicide attempt during 2006-2007. Their mean ± SD age was 36.2 ± 14.4.

Healthy controls

Forty persons from the National Registration were randomly selected and invited to participate in the study. Nine of them were excluded because of disease, and one changed his mind. Twenty-two healthy controls agreed, but 19 actually participated (9 males and 10 females) and their mean ± SD age was 34.7 ± 10.8.

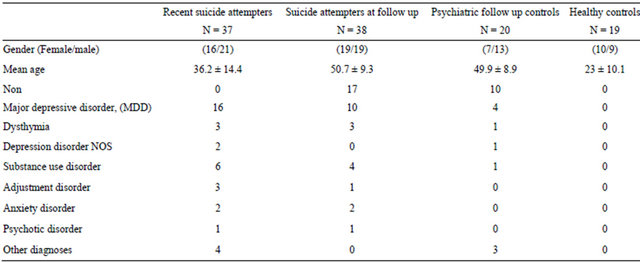

Diagnostic procedures

The suicide attempters at long term follow up were originally (at index) diagnosed by two independent psychiatrists according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 3rd edition, revised [14]. After the diagnostic procedure, they reached consensus on the main diagnosis. At the follow up setting these persons went through a semi-structured interview SCID I and II [15] by a specialist in psychiatry together with a resident in psychiatry, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition [16] was used. The psychiatric controls at follow up were evaluated from the same semi-structured interview as the suicide attempters at long term follow up. The recent suicide attempters went through a structured interview by a specialist in psychiatry and were diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition [16] and from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV (SCID) I and II [15]. The healthy controls were medically examined by a resident in psychiatry and evaluated from the same semi-structured interview as the psychiatric controls at follow up, concerning current or prior psychiatric or somatic diseases. All included healthy controls had an average lifestyle and denied earlier or current psychiatric disease, alcohol or other substance abuse of their own, or of their first degree relatives (Table 1).

2.2. COPE-Assessments

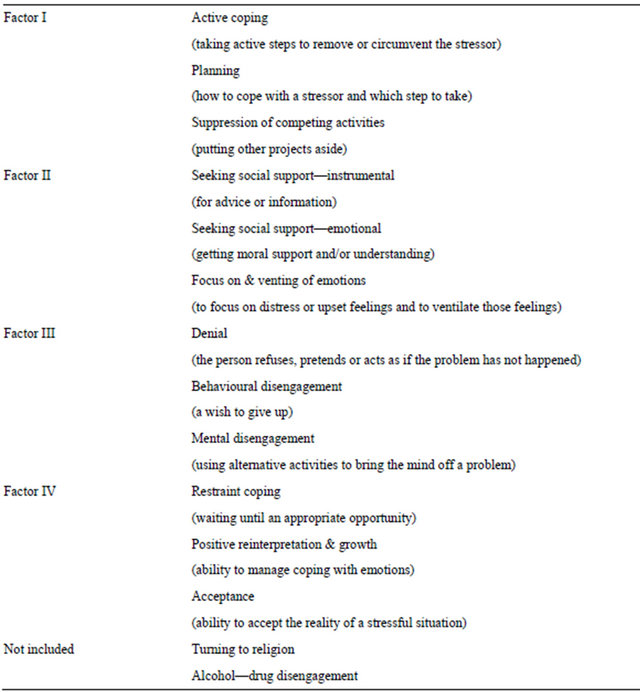

We used the original edition of COPE [5] which was translated from English into Swedish by support from the Lund University Department of Languages. The inventory interprets 14 types of coping-styles. A five-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (a lot) was used. The 56 item version applied in this study was classified into 12 conceptually distinct coping subscales or indexes, where each index was composed of four items. Carver et al. [5] conducted a factor analysis based on the 14 subscales, which resulted in four factors (Table 2). The fourth factor did not include the item “turning to religion and humour” because of low predictive validity.

Problem focused coping contains: active coping, planning, suppression of competing activities, restraint coping and seeking social support—instrumental. Emotional coping contains: seeking social support—emotional, positive reinterpretation & growth, acceptance, and denial. Avoidance coping contains: focus on & venting of emotions, behavioural disengagement, and mental disengagement.

2.3. Statistics

As the data were not normally distributed, non-parametric statistical methods were used. Mann Whitney U-test was used to compare two groups of coping strategies and Kruskal Wallis H was used to compare coping strategies between all groups. We used the Pearson Chi-square to compare gender differences in the different study groups. All statistical calculations were made by use of the Statistical package for the Social Sciences, SPSS, version 15.

2.4. Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Sweden and all participants gave written informed consent.

Table 1. Principal axis I diagnosis of subjects.

Table 2. COPE-factors based on the subscales of Carver et al. (1989).\

2.5. Definition of a Suicide Attempt

In this study, we regard a suicide attempt as a life threatening behaviour with the intent of jeopardizing one’s own life, or to give an appearance of such intent, but which has not resulted in death [17].

3. RESULTS

There were no significant gender differences between the different study groups, i.e. the recent suicide attempters, suicide attempters at follow up, psychiatric controls at follow up and healthy controls. As expected, healthy controls and the recent suicide attempters were significantly younger than the followed up study groups (p ≤ 0.000).

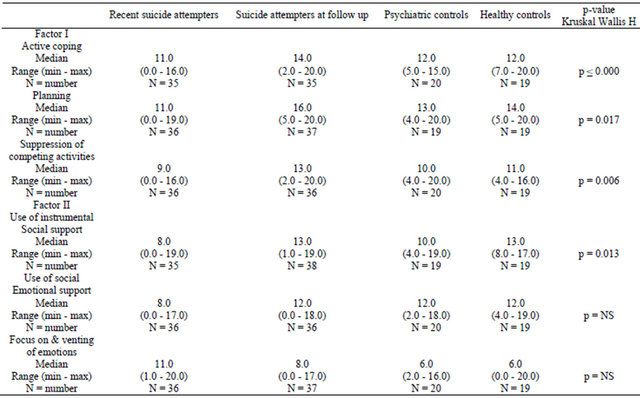

3.1. Factor I. Active Coping, Planning and Suppression of Competing Activities

There were significant differences between the study groups. Suicide attempters at follow up had the highest value in factor I (median 42.0; total score 60; range 11.0 - 58.0), followed by healthy controls (median 38.0; range 21.0 - 56.0), psychiatric controls at follow up (median 34.0; range 17.0 - 53.0), and the recent suicide attempters (median 31.0; range 0.0 - 48.0), respectively (Kruskal Wallis H p = 0.001) (Table 3(a)).

3.2. Factor II. Seeking Social Support Instrumental and Emotions, and Focus on & Venting of Emotions

There were no significant differences in factor II between the study groups (Table 3(a)).

3.3. Factor III. Denial, Behavioural Disengagement and Mental Disengagement

The recent suicide attempters had the highest scores in factor III (median 25.0; total score 60; range 4.0 - 52.0), followed by psychiatric controls at follow up (median 18.0; range 6.0 - 25.0), suicide attempters at follow up (median 10.0; range 1.0 - 37.0) and healthy controls (median 10.0; range 0.0 - 17.0) Kruskal Wallis H (p ≤ 0.000). The data of subscales of this factor are shown in Table 3(b) and every subscale has a total score 20.

3.4. Factor IV. Restraint Coping, Positive Reinterpretation & Growth and Acceptance

Suicide attempters at follow up had the highest scores in factor IV (median 40.0 total score 60; range 8.0 - 52.0), followed by healthy controls (median 40.0; range 25.0 - 48.0), psychiatric controls at follow up (median 34.0; range 14.0 - 57.0), and the recent suicide attempters (median 30.0; range 3.0 - 48.0) Kruskal Wallis H (p ≤ 0.000, Table 3(b)). The subscales differences in factor IV are reported in Table 3(b) and every subscale has a total score 20 (Table 3(b)).

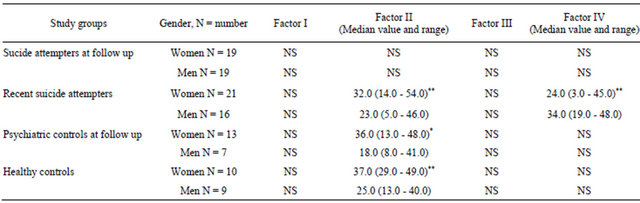

3.5. Gender Differences and COPE Factors

There were no significant differences between men and women in the COPE factors I - IV of suicide attempters at follow up. In the other study groups (the recent suicide attempters, psychiatric controls and healthy controls), there were significant gender differences in COPE factor II (seeking social support instrumental and emotions, and focus on & venting of emotions). In the recent suicide attempters, men had significantly lower scores in factor II (median 23.0; range 5.0 - 46.0) than women (median 32.0; range 14.0 - 54.0); Mann Whitney U-test (p = 0.003). In psychiatric controls at follow up, men had significantly lower scores in factor II (median 18.0; range 8.0 - 41.0) than women (median 36.0; range 13.0 - 48.0); Mann Whitney U-test (p = 0.04), and in healthy controls, men had significantly lower scores in factor II (median 25.0; range 13.0 - 40.0) than women (median 37.0; range 29.0 - 49.0); Mann Whitney U-test (p = 0.002) (Table 4).

In the other factors, i.e. I, III and IV, there were no significant gender differences in suicide attempters at follow up, psychiatric controls, or in healthy persons. However, women in the study group of the recent suicide attempters had significantly lower scores in factor IV (restraint coping, positive reinterpretation & growth and acceptance) (median 24.0; range 3.0 - 45.0) than men (median 34.0; range 19.0 - 48.0); Mann Whitney U-test (p = 0.004) (Table 4).

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present investigation was to explore whether suicide attempters more often than comparison groups used deviant coping strategies at stressful situations, regardless of when they were studied. We showed that recent suicide attempters and followed up psychiatric controls without a history of suicidal behaviour had more maladaptive coping strategies than suicide attempters at follow up and healthy controls, respectively.

A weakness of the present study is that suicide attempters were not studied prospectively, which means that we were unable to follow coping capacities over time in the same individual, and in relation to treatment and further experiences of life. Another weakness is that the younger controls and the recent suicide attempters were significantly younger than the followed up study groups. We know that coping changes partly with age, depression and attempt status [18].

The suicide attempters at follow up had already participated in our study at index, which means that they

Table 3. Cope subscales of recent suicide attempters, suicide attempters at follow up, psychiatric and healthy controls: (a) Factors I and II; (b) Factors III and IV.

(a)

(b)

Table 4. Gender differences in different COPE factors.

Statistics: Women vs. men, Mann Whitney U-test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

were familiar with our study, and were therefore probably curious to participate in a follow up investigation. However, the psychiatric controls at follow up had never before participated in a research study, which could explain our difficulties to recruit them.

4.1. Maladaptive Coping Capacity

We found that the recent suicide attempters and followed up psychiatric controls without a history of suicidal behaviour, more often than others used maladaptive coping strategies, such as denial, behavioural and mental disengagement. This means that individuals belonging to these groups, often refused to accept the problem or pretended or acted as if the problem had not appeared, had urges to give up and/or used alternative activities to bring the mind away from the problem. Our findings are similar as the results by Pollock et al. [19], who found that suicide attempters were less effective in problem solving than nonsuicidal individuals or healthy controls. In disagreement with our long term follow up findings, they observed that problem solving persisted over a 6 weeks’ time. Previous researchers [3,20,21] have found that suicide attempters preferred to use avoidance coping, which is consistent with our findings concerning suicide attempters in the emergency situation. Our results are also similar to those by Brown et al. [22] who examined emotions and coping strategies among college students with recent, past, and no history of deliberate self-harm behaviour. Among recent and past self-harmers, they found two significant maladaptive coping strategies, i.e. behavioural disengagement strategies and denial. These two study groups also had more negative emotions, such as fear, hostility, guilt and sadness, than had students without a history of self-harm. This means that selfharmers, regardless when studied, were likely to quit, give up or use less effort, when confronted with a challenge situation. Our findings and the ones by Brown et al. [22] are consistent with results reported in the Horesh et al. [23] study. They compared 30 psychiatric in-patients, admitted because of suicidal behaviour, with 30 nonsuicidal psychiatric in-patients and 32 healthy controls, and found that the suicidal group used more maladaptive coping strategies than the others, such as minimizing the importance of the problem. Their suicidal group also tried to avoid the problem through tension-reduction activities. Such strategies are similar to the ones described in the COPE inventory scales of mental disengagement, where our recent suicide attempters scored high. One reason why our recent suicide attempters often used maladaptive coping strategies could be that they suffered from MDD [24].

4.2. Adaptive Coping Capacity

In our study, suicide attempters at follow up and healthy controls more often than the others used adaptive coping styles, such as active coping, planning, suppression of competing activities, positive reinterpretation & growth, and acceptance. Similarly to our healthy controls, Brown et al. [22] found that persons without a history of deliberate self-harm used more adaptive strategies, such as positive reinterpretation, acceptance and planning, than did recent and past self-harmers. However in their study, the group of past self-harmers (more than 12 months ago) had not improved their coping style. In our study, suicide attempters at long term follow up had a coping style, comparable to that of healthy controls. The reason for this is probably that in many cases their psychiatric state and social function had improved due to adequate treatment interventions. Our study somewhat supports findings by Brauns et al. [25]. They performed a follow up study, in which patients with a previous suicide-attempt were re-examined 3 - 8 years later, and compared to inpatients who recently had made a suicide attempt. They evaluated the patients by using semi-structured interviews combined with the self-rating scale Stress-CopingQuestionnaire. They found that cognitive strategies in the sense of positive self-instruction were used more often among those who were followed up, and this leads to a direct and constructive control of the patient’s own behaviour and an active stress-coping. Brauns et al. [25] concluded that an important focus of therapy should be the support of active strategies for coping with interpersonal problems.

In our study, another adaptive coping strategy, i.e. seeking social support—instrumental, was scored lower by the recent suicide attempters than suicide attempters at follow up, or healthy controls. This means that the recent suicide attempters were less prone to seek advice and information than the others. This is an important finding, since social support can exert a protective influence against stressors and buffer against the outcome of a stressful event [26]. Maybe suicide attempters at follow up had learned the importance of social support. McAuliffe et al. [27], who investigated parasuicide (deliberate self-harmers and suicide attempters), had a similar result concerning repeaters of parasuicidal acts in their follow up study 15 months later. They suggested that the phenomenon of parasuicide could be gender related, as males are less likely seek social support than females. This is in line with findings in our study. Men had significantly lower scores on factor II, seeking social support instrumental, seeking social support emotional and focus on & venting of emotions in every study group except in suicide attempters at follow up. After a suicide attempt, one part of the treatment is to help the suicidal individual to seek social support whenever feeling suicidal [28].

In the study group of the recent suicide attempters, women had lower scores than men in the coping strategies; restraint coping, positive reinterpretation & growth and acceptance. This might be explained by an influence of a DSM IV, axis II diagnosis, and especially a borderline personality disorder, as factor IV deals with coping strategies, which ask for emotional control, acceptance of the situation, and to wait for an appropriate opportunity.

4.3. Coping Strategies in Relation to Illness

Many previous reports have suggested that coping strategies have a relation to the state of illness, e.g. symptoms of depression, anxiety and mood, such as anger and hopelessness [19,29,30]. Elliott et al. [30] used the COPE to find out the kind of coping strategies that were related to hopelessness among self-poisoners, and noticed that these patients often used problem focused strategies when they felt less hopeless. Twelve years after a suicide attempt and due to professional care and treatment, most of our patients probably felt more hopeful about the future and therefore used more adaptive coping strategies. It is therefore important to determine the influence of psychiatric state on measures of coping. In our study, there were no significant differences in coping strategies used by recovered subjects and those who were still ill during follow up. In the group of suicide attempters at follow up, the improved ones had significantly higher scores on the coping strategy called positive reinterpretation and growth than had the still ill. This reflects a change of adaptive coping which means an improvement in coping with emotions.

4.4. Conclusion

Our findings make us tempt to suggest that suicide attempters have improved their coping capacity twelve years later, so that they use more adaptive problem solving strategies than before. The healthy people deal with stressful life events by active approaching to the stressor. Both followed up psychiatric controls, which were once treated because of similar diagnoses as the index suicide attempters, and recent suicide attempters are more often used maladaptive strategies such as avoidance. It is interesting in our study, suicide attempters at follow up and matched psychiatric controls had different coping approaches. This might be an effect of discrepant outpatient treatment strategies. Further examinations of the possible influence of long term professional care and treatment of suicide attempters after hospitalization will be necessary in a future comprehensive and prospective follow up study.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participating subjects in the study. The Swedish Research Council no. 14548-04-3, the Scania ALF foundation and Sjöbring Foundation gave financial support. Professor Arnstein Finset, Oslo, introduced us to the problem of coping and to the COPE-instrument and offered a valuable contribution to the intellectual development of the article, professor of the English language at Lund University, Sven Bäckman.

REFERENCES

- Folkman, S., Lazarus, R.S., Gruen, R.J. and Delongis, A. (1986) Appraisal, coping, health status and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 571-579. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.571

- Evans, J., Williams, J.M., O’Loughlin, S. and Howells, K. (1992) Autobiographical memory and problem-solving strategies of parasuicide patients. Psychological Medicine, 22, 399-405. doi:10.1017/S0033291700030348

- Edwards, M.J. and Holden, R.R. (2001) Coping, meaning in life, and suicidal manifestations: Examining gender differences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57, 1517- 1534.

- Dieserud, G., Roysamb, E., Ekeberg, O. and Kraft, P. (2001) Toward an integrative model of suicide attempt: A cognitive psychological approach. Suicide Life Threat Behave Summer, 31, 153-168.

- Carver, S., Scheier, M. and Weintraub, J. (1989) Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267- 283. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

- Taylor, S.E. and Stanton, A.L. (2007) Coping resources, coping process, and mental health. Clinical Psychology, 3, 377-401. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520

- Sunnqvist, C., Persson, U., Westrin., A., TräskmanBendz, L. and Lenntorp, B. (2012) Grasping the dynamoics of suicidal behaviour: Combining time-geographic life charting and COPE ratings. Journal of Psychiatric Mental Health and Nursing, 20, 336-344. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01928.x

- Becker-Weidman, E.G., Jacobs, R.H., Reinecke, M.A., Silva, S.G. and March, J.S. (2010) Social problem-solving among adolescents treated for depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1, 11-18. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.08.006

- Schotte, D.E. and Clum, G.A. (1982) Suicide ideation in a college population. A test of a model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 690-696. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.50.5.690

- Linehan, M.M., Camper, P., Chiles, J.A., Strohsahl, K. and Shearin, E. (1987) Interpersonal problem solving and parasuicide. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11, 1-12. doi:10.1007/BF01183128

- Orbach, I., Bar-Joseph, H. and Dror, N. (1990) Styles of problem solving in suicidal individuals. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviour, 20, 56-64.

- Williams, F. and Hasking, P. (2010) Emotion regulation, coping and alcohol use as moderators in the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and psychological distress. Prevention Sciences, 11, 33-41. doi:10.1007/s11121-009-0147-8

- Marty, M.A., Segal, D.L. and Coolidge, F.L. (2010) Relationships among dispositional coping strategies, suicidal ideation, and protective factors against suicide in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 8, 1015-1023. doi:10.1080/13607863.2010.501068

- American Psychiatric Association (1987) Diagnostic and statistic manual of mental disorders. 3rd Edition, APA, Washington.

- First, M.B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B.W. and Benjamin, L.S. (1997) Structured clinical interview for DSM IV axis I and II disorders. APA, Washington.

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistic manual of mental disorders. 4th Edition, APA, Washington.

- Beck, A.T., Davis, J.H., Frederick, C.J., Perlin, S., Pokorny, A.D., Schulman, R.E., Seiden, R.H. and Wittlin, B.J. (1972) Classification and nomenclature. In: Resnik, H.L.P. and Hathorne, B.C., Eds., Suicide Prevention in the Seventies, Government Printing Office, Washington, 7-12.

- Nrugham, L., Holen, A. and Sund, A.M. (2012) Suicide attempters and repeaters: Depression and coping: A prospective study of early adolescents followed up as young adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 200, 197-203. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318247c914

- Pollock, L.R. and Williams, J.M. (2004) Problem-solving in suicide attempters. A brief communication. Psychological Medicine, 34, 163-167. doi:10.1017/S0033291703008092

- Josepho, S.A. and Plutchik, R. (1994) Stress, coping, and suicide risk in psychiatric in patients. Suicide and LifeThreatening Behaviour, 24, 48-57.

- Marusic, A. and Goodwin, R.D. (2006) Suicidal and deliberate self-harm ideation among patients with physical illness: The role of coping style. Suicide and LifeThreatening Behaviour, 36, 323-328. doi:10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.323

- Brown, S.A. and Williams, K. (2007) Past and recent deliberate self-harm: Emotion and coping strategy differences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 791-803. doi:10.1002/jclp.20380

- Horesh, N., Rolnick, T., Iancu, P., Dannon, E., Lepkifker, E., Apter, A. and Kotler, M. (1996) Coping styles and suicide risk. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 93, 489-493. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10682.x

- Kelly, M.A., Sereika, S.M., Battista, D.R. and Brown, C. (2007) The relationship between beliefs about depression and coping strategies: Gender differences. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46, 315-332. doi:10.1348/014466506X173070

- Brauns, M.L. and Berzewski, H. (1988) Follow up study of patients with attempted suicide. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 34, 285-291. doi:10.1177/002076408803400406

- Milne, D. and Nertherwood, P. (1997) Seeking social support: An observational, illustrative and instrumental analysis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25, 173-185. doi:10.1017/S1352465800018373

- McAuliffe, C., Keeley, H.S. and Corcoran, P. (2002) Problem solving and repetition of Parasuicide. Behvioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 30, 385-397. doi:10.1017/S1352465802004010

- Hawton, K. and Van Heeringen, K. (2002) The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

- Cannon, B., Mulroy, R., Otto, M.W., Rosenbaum, J.F., Fava, M. and Nierenberg, A.A. (1999) Dysfunctional attitudes and poor problem solving skills predict hopelessness in major depression. A brief report. Journal of Affective Disorders, 55, 45-49. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00123-2

- Elliot, J.L. and Frude, N. (2001) Stress, coping styles, and hopelessness in self-poisoners. Crisis, 22, 20-26. doi:10.1027//0227-5910.22.1.20