Sociology Mind 2011. Vol.1, No.4, 177-182 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/sm.2011.14023 Urban Violence in Northern Border of Mexico: A Study from Nuevo León State* Arun Kumar Acharya Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico. Email: acharya_77@yahoo.com Received July 29th, 2011; revised September 2nd, 2011; accepted October 3rd, 2011. Urban violence has reached record level in many nations, and having devastating impact on people’s health and livelihood as well as economic prospects. Today, for millions of people around the world, violence, or the fear of violence, is a daily reality. In Mexico since the year 2006 the northern border states are become more violent due to fight against the drug trafficking. In this study, we have taken Nuevo León state as area of study, and we have seen from the result; that urban violence in Nuevo León has increased in an unprecedented manner during last few years. Much of this urban violence is a consequence of rural-to-urban migration and exponential ur- banization. We have also seen in the study that urban violence is a multi-factorial phenomena and main reason behind this is inequality among city dwellers. This is a potential source of frustration which increasing risk of urban violence, especially if ce rtain groups are underprivileged and suffers from s oc ia l exc lusion. Keywords: Urban Violence, Drug trafficking, Nuevo Leon, Mexico Introduction Over the last 50 years, the world has witnessed a dramatic growth of its urban population. The speed and the scale of this growth, especially concentrated in the less developed regions, continue to pose formidable challenges to individual countries as well as to the world community. According to United Na- tions in the year 2009, the number of people living in urban areas 3.42 billion had surpassed the number living in rural areas 3.41 billion, and after that world has become more urban than rural (United Nations, 2009). In 1900 only 15 percent of the world’s population lived in cities. The 20th century transformed this picture, as the pace of urban population growth accelerated very rapidly in about 1950. Sixty years later, it is estimated that more than half of the world’s people lives in cities. The world is undergoing the largest wave of urban growth in history. For the first time in history in 2009, more than half of the world’s population will be living in towns and cities. By 2030 this number will swell to almost 5 billion, with urban growth concentrated in Africa and Asia. While mega-cities have captured much public attention, most of the new growth will occur in smaller towns and cities, which have fewer resources to respond to the magnitude of the change. In principle, cities offer a more favorable setting for the resolution of social and environmental problems than rural areas. Cities generate jobs and income. With g ood go verna nce, they can deliver education, health care and other services more efficiently than less densely settled areas simply because of their advantages of scale and proximity (United Nations, 2009). However, the fact that such large percentage of people in many developing countries are young means that urban popula- tion growth will continue rapidly for years to come. Moreover, impoverished urban women are significantly less likely than their more affluent counterparts to have access to reproductive health or contraception. Not surprisingly, they have higher fer- tility rates. Migration is a significant contributor to urbanization, as people move in search of social and economic opportunity. Environmental degradation and conflict may drive people off the land. Often people who leave the countryside to find better lives in the city have no choice but to settle in shantytowns and slums, where they lack access to decent housing and sanitation, health care and education in effect, trading in rural for urban poverty. On the other hand, this rapid urbanization has also brought with it immense social and economic disruption, and with it, increased crime and violence in many cities. For mil- lions of people around the world violence, or the fear of vio- lence, is a constant reality. Urban violence is a serious impede- ment to development and to poverty reduction (United Nations, 2009). In Latin America, for example, recent work at the World Bank has suggested that rapid rates of urbanization are associ- ated with higher levels of homicide (Fajnzylber, et al., 1998, cited by Rodgers, 2010), while Inter-American Development Bank researchers Alejandro Gaviria and Carmen Pagés (2002, cited by Rodgers, 2010) find that a household in a city of more than one million inhabitants was 71 per cent more likely to be vic- timized than a household in a city of between 50,000 and 100,000 inhabitants (Rodgers, 2010). The classic article of Louis Wirth entitled ‘Urbanism as a Way of Life’ Chicago School of Sociology, argues that cities are large, dense settle- ments of socially heterogeneous individuals and that, as a result, they promote high levels of violence, insecurity, and disorder, insofar as large numbers lead to impersonal social contact, high density produces increased competition, and heterogeneity induces differentiation and stratification. Wirth’s theoretical statement has come “to occupy by itself most of the central ground in its sort of thinking about urban life” (Hannerz, 1980, cited by Rodgers, 2010); yet, the fact that not all cities are af- fected by high levels of violence and disorder—even when equivalent in size, density, and heterogeneity—raises questions concerning its universal applicability. Considering the above discussion, in this paper I have tried to explore how the urban violence has increased in the last few years, also in this paper I have explained the possible factors for this growing phenomena. *This study was supported by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACYT), Mé xico CB-2007/83716.  A. K. AC HARYA 178 Growth and Forms of Urban Violence Insecurity has become a fact of life across cities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. As a result of urban in-migration, urban areas can be socially, culturally, ethnically, and relig- iously diverse and some see this as an important contributory factor in making them at risk of conflict and violence (Beall, Gua-Khasnobis, and Kanbur, 2010). The broad literature on social movements and collective action offers a number of in- sights into how increasing urban population pressure might transform into political violence. Possible theoretical ap- proaches range from almost deterministic assumptions about ethnic hatreds and associated security dilemmas (Horowitz, 1985; Kaufmann, 1996; Posen, 1993, cited by Østby, 2010) via modernization-based arguments of radicalization of aggrieved, unemployed youths (Huntington, 1996, cited by Østby, 2010) to classic theories of structural inequalities and relative depri- vation (Gurr, 1970, cited by Østby, 2010). Common to all of these contributions is their attention to the distribution of op- portunities and privileges among the urban population. Simi- larly, the mixing of ethnicities and shifting demographic com- position of urban centers is often cited as a major destabilizing factor. On the other hand, the link between urbanization and socio- economic development is rarely disputed. However, in many developing countries around the world, economic growth has not resulted in prosperity for all. Poverty has long been recog- nized as an important risk factor associated with crime and violence in urban areas (UN Habitat, 2008). In the coming decades, increasing numbers of cities in de- veloping countries will have a high proportion of their popula- tion living in poverty, and will also suffer from severe envi- ronmental degradation. Poor environmental conditions are most likely to affect the poor residents in megacities. Although city- wide violence will have worldwide consequences, raising con- cerns for regional stability and financial markets, it will more frequently consist of “the poor preying upon the poor” (Bren- nan, 1999, cited by Østby, 2010). Assuming that urban socio- economic deprivation will lead to both grievances and less opportunity costs for the poor associated with engaging in vio- lent activities. While urban violence may be associated with poverty and other forms of absolute deprivation, it is important to note that there are many poor communities in cities around the world where crime levels are low. A more important factor than pov- erty in affecting urban violence may be inequality. Intra-city inequalities have risen as the gap between rich and poor has widened, e.g. as a result of key exclusionary factors relating to unequal access to employment, education, health and basic infrastructure. In many developing countries, particularly in Africa and Asia, the formal employment sector has been unable to provide adequate jobs for rapidly growing urban populations (Thomas, 2008, cited by Østby, 2010). Perceptions of declining living conditions in big cities have been buttressed by literature that documents substantial and growing inequality within cities (Brockerhoff & Brennan, 1998, cited by Østby, 2010). The problem, hence, does not seem to be urbanization per se, but rather the fact that it has not resulted in more equal resource distribution. Such patterns of urban inequality have provoked ominous vi- sions of future cities. For example, Massey (1996) argues that urban inequality entails escalating crime and violence punctu- ated by sporadic riots and increased terrorism as class tensions rise. This perspective derives from a rich body of social conflict theory (often associated with Marx), and from a common idea that the disadvantaged of large cities will challenge the estab- lished urban social order violently. It is in relation to basic ur- ban services that urban inequalities are often most evident, with poor slum-dwellers paying water vendor up to fifty times more for clean water than a resident living a stone’s throw away in a neighborhood which is fully serviced (Beall, Gua-Khasnobis, & Kanbur, 2010). The “ecological” model explains violence as the product of a combination of factors at different levels—individual, interper- sonal or relational, institutional or communitarian, structural or societal (Rosenberg, et al., 2002; Agostini, et al. , 2010). 1. Economic violence Most of the authors concerned with economic violence agree that urban inequality and poverty produce unequal access to economic opportunity and are the significant determinants of crime and violence (Bourguignon, 1999; Fajnzylber, Loayza, & Lederman, 2002; Muller, 1985; Agostini, et al., 2010): “due to frustration and insecurity and the presence of absolute and rela- tive poverty, the urban poor are forced to resort to crime and violence…rising expectations and a sense of moral outrage that some members of society are getting rich while others are de- nied even the most basic levels of existence has been a well known source of…discontent in the poorest as well as richest countries” (Zaidi, 1999; Agostini, et al., 2010). A further condition for economic violence to occur is the ex- istence of the informal sector and the discriminatory treatment of the state and the elite towards it. As De Soto (1989, Agostini, et al., 2010) outlines, the presence of the informal sector ex- presses the incapacity of the legal economy and the judicial system to guarantee to the majority of the population economic rights and participation. When this is the case, the poor find a means of gaining livelihood in the illegal economy. 2. Political violence Political violence contains a wide range of violent outcomes, one of these is the normalization of violence which requires a system of norms, values or attitudes which allow, or even stimulate, the use of violence (Agostini, et al., 2010), and mainly culminates in a form of state violence. Another form of political violence perpetrated by the state is the lack of reform within the police and judiciary or the inability to provide le- gitimate institutional control over violence. This de-legitimisation is described in the literature, as it relates to drugs, as what Dowdney calls ‘narcocracy’ (Winton, 2004; Agostini, et al., 2010). Drug trafficker left as rulers of poor communities and low-income neighborhoods, impose their own norms “con- structing a simulacrum of governmental control” (Pengalese, 2005; Agostini, et al., 2010). The state’s failure in providing security for the citizenship opens the path to a wide range of arrangements that are conducive to viol e nce. 3. Social violence The label “social violence” is used for describing a wide range of acts, which depending on the perspective taken can exemplify economic or political violence, as well as social vio- lence (Winton, 2004; Agostini, et al., 2010). In this vein, forms of social violence can coexist with, or be motivated by, eco- nomic violence. This is clear in the case of gangs. Considering the gang phenomenon from an economic perspective, its eco- nomic nature is clear, but here it is important to also consider the social aspect of the phenomenon. Gangs are formed as a response to social and economic exclusion of youth and repre- sent an alternative societal membership in communities where social capital is lacking (Winton, 2004; Rodgers, 2005a, 2006a;  A. K. ACHARYA 179 Trend of Urbanization in Monterrey Metropolitan Region Moser & Winton, 2002; Agostini, et al., 2010). Urbanization in Nuevo León State The Monterrey Metropolitan Region (MMR) is the third largest city in Mexico after the Mexico DF and Guadalajara. As we have seen in earlier discussion; it comprises major part of the state’s population. In the Table 2 and Figure 2, I have ana- lyzes the total population of MMR and its share in overall state’s population. In the year 2005, the Monterrey Metropoli- tan region had 3.6 million population out of 4.1 million state’s population (86 percent) and 90 percent of the total state urban population. This higher concentration of population in one cen- ter dominates MMR as a Monocentric urban zone in the state. The larger concentration of urban population in MMR is ac- companied by an increasing primacy in state as well as in coun- try because of economic importance. Nuevo León is one of the most urbanized state in Mexico. In the year 1930, 41 percent of the state population was living in urban areas and it reaches to 95 percent in 2005. The state ob- served its higher urbanization rate during 1950-1970, afte rwar ds the growth rate has declined due to greater staturation as well as higher international migration from Mexico to United states of America as well as in particular from Nuevo León, thus in 2005 the growth rate was only 2.09 percent. In Nuevo León major part (85 percent) of the state population and 90 percent of the total state urban population concentrated in Monterrey Metro- politan Region. Monterrey Metropolitan Region is conform with 9 out of 51 districts of the state (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Table 1. Urbanization process in Nu ev o Le ón s ta te . Year Total Population Total urban Population Percentage of urban population Growth rate in percentage 1930 417,491 172,175 41.24 - 1950 740,191 416,605 56.28 7.0 1970 1,694,689 1,296,843 76.52 10.56 1990 3,098,736 2,872,967 92.71 6.07 2000 3,834,141 3,605,616 94.03 2.55 2005 4,199,292 3,982,994 94.84 2.09 Source: INEGI, 2010. Table 2. Trend of urbanization in Monterrey Metropolit an Region. Year Total Population Total urban Population Total population of MMR Share of population of MMR in state population Share of population MMR in state urban population 1930 417,491 172,175 164,210 39.0 95.3 1950 740,191 416,605 389,629 52.6 93.5 1970 1,694,689 1,296,843 1,254,691 74.0 96.7 1990 3,098,736 2,872,967 2,573,527 83.0 89.6 2000 3,834,141 3,605,616 3,243,466 84.6 90.0 2005 4,199,292 3,982,994 3,598,597 86.0 90.1 Source: INEGI, 2010. Figure 2. Figure 1. Trend of urbanization in Monterrey Metropolit an Region. Urbanization process in Nuevo Leó n s ta te.  A. K. AC HARYA 180 The trend of urbanization in MMR cannot be understood properly without analy zing the spatial dimension of urbanization and urban growth of the region. As it is describes earlier, the metropolitan region is conform with nine municipalities of 51, such as: Monterrey, San Pedro Garza Garcia, San Nicolas de los Garza, Guadalupe, Santa Catarina, Juarez, General Escobedo, Apodaca and Garcia. In Table 3, I have presented the trends of population growth in metropolitan region according to munici- palities. We can see that in 1930 the total population of the region was 164,210 and after the 75 years (in 2005) the popula- tion increases 22 times and reaches to 3,598,597. Whilst on regional distribution of population, we can see that during 1930 only municipality of Monterrey had more than 100 thousands population and it was the mostly populated compa- rable to municipalities of city center and peri-urban region. After the year 1930, the population in all municipalities started growing due to economic miracle in the region and today all municipalities have more than 150 thousands population. For example municipality of Monterrey has more than 1 million population. Growth of Urban Violence in Nuevo León State The urban violence in Nuevo León has steadily increased since the President Calderon imposed his plan to combat the drug trafficking in México. As Nuevo León is border state be- tween Mexico and United States, it acts as a transit point for drugs to United States. On the hand, Monterrey is the capital city of Nuevo León also known as economic capital of Mexico, received migrants from all over the country. Many migrate to city in search of an employment and better life style, thus city has higher socio-especial segregation. Due to higher internal migration as well as for drug trafficking the cities has become more violent since last five years. In the following table we can see that the total number of urban violence registered in the state was 70,431, whereas in 2009 and 2010 it decline to 62,482 and 66,367 (see Table 4). Table 3. Types of urban violence in Nuevo L eó n s ta t e. Urban violence 2008 2009 2010 Property Robbery 12,425 4677 4373 Theft 3637 3689 5014 Vehicle Robbery 10,936 12,797 15,493 Murder 732 705 1269 Gang violence 1942 1545 1657 Source: Government of Nuevo León, 2011. Table 4. Growth of urban violence in Nuev o L e ón s ta t e. Year Total number of urban violence 2008 70,431 2009 62,482 2010 66,367 2011 23,347 Source: Government of Nuevo León, 2011. Causes of Urban Violence There is no single cause that leads the urban violence. The accumulation of risk factors is associated with an increased tendency of being a victim or a perpetrator of violence. Con- versely, protective factors can be understood as characteristics of an individual and his/her environment that strengthen the capacity to confront stre sses without the use of violence. In the field of violence prevention, these factors are generally under- stood within an “ecological model.” Employed predominantly within the public health approach (WHO, 2002), this model outlines factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and society levels. Most individuals are able to cope with low levels of risk in positive ways, even while growing up in high-risk environments (World Bank, 2008; O’Toole, 2002), then the question arises, why are some individuals able to survive even in high-risk environments, while others are not? It is mainly because of accumulation of different risk and protective factors. Studies in the United States (Sameroff, et al., 1987; Dunst, 1993, in World Bank 2011) suggest that the accumulation of risk is more influential than the impact of any one risk factor. Conversely, protective factors accumulate to facilitate healing and decrease the propensity for violence. Generally speaking, “risk accumulates; opportunity ameliorates” (Garbarino, 2001, in World Bank 2011). Much of the evidence on violent behav- ior points to the importance of a sense of social connection as an important protective factor against violent behavior. In this matter, some research indicates that, a child exposed to violence in her home will look first for refuge in her com- munity. Indeed, these family experiences can often be mitigated by positive support at school, community groups, and other bodies. Studies of the United States (Blum, et al., 2002, in World Bank 2011) and various countries across Latin America and the Caribbean (World Bank, 2008) found that the impacts of exposure to violence in the home can be mitigated by a sense of social connection to school and/or community. Other studies in the U.S. have found that a sense of social connection, in- cluding opportunities for participation in social and economic life, help protect against violent behavior (Garbarino, 1995; Benard, 1996, in World Bank 2011). Studies on protective factors in North America identified 40 different factors, of which half were individual characteristics, and half were associated with the community and home envi- ronment (Search Institute, 1998). These findings suggest that community-level factors are at least as important as individual level factors in protecting against violent behavior. Access to employment opportunities often is set forth as a protective fac- tor against violent behavior. However, in the literature, the relationship between employment, especially youth employ- ment, and violence outcomes is inconclusive. One recent study of unemployment and crime in France over 1990-2000 found a positive, causal effect of unemployment on property crimes and drug offenses, yet no effect on rapes, homicides, or other vio- lent crimes (Fougere, et al., 2009, in World Bank 2011). Other studies of crime and unemployment generally have found a positive relationship, but the effect is not always sig- nificant; and some have found a negative relationship (Chirico, 1987, in World Bank 2011). This distinction is important, as many programs promote youth employment as a means to combat both crime and violence. Lamas and Hoffman (2010, in World Bank 2011) note that unemployment can lead to bore- dom and depression, which, in turn, are connected to substance abuse and perpetration of violence. These dynamics have been documented in qualitative studies (Moser & McIlwaine, 2004,  A. K. ACHARYA 181 in World Bank 2011), and particularly in refugee camps in various contexts (Benjamin, 1996, in World Bank 2011). It could be that the type of employment is equally, or even more, important than the fact of employment itself. In particular, the type of social connection created by access to employment could be an important factor. Taking into consideration, in the follow- ing figures we have identified t he possible key factors as sociated with the urban violence in Nuevo León (see Table 5). Conclusion Urban populations, particularly in developing countries, will continue to grow over the next decades, and the total urban population in the world is expected to nearly double over the next 40 years. Hence, enhancing our knowledge on the deter- minants of urban disturbances should be given top priority, not least because citywide violence may have serious global effects, such as destabilizing worldwide financial markets and destroy- ing infrastructure, thereby affecting already fragile national economies, or igniting violence in entire regions. It is estimates that in the next two decades the urban violence will rise 3 to 5 percent (Rosan, Ruble, & Tulchin, 2000). In the third world countries and Eastern Europe, the urban violence has increases and the figures of past few years showing an alarming scenario. The development of drug related organized crime playing a major contributor to the level of urban violence especially as we have observed in the case of Mexico basically in Nuevo Table 5. Key factors of urban violence in Nu e vo L e o n s t at e . Level Key Factors Gender Age Race Ethnicity Engagement in Risky behaviors (Alcohol, Drugs, sexual behaviors) Individual Employment status Family violence Family break down Family Negligence of parent Low access of education High levels of neighborhood crime and violence Communal Easy availabil i t y of drugs, a l cohol Rapid urbanization Migration Demographic factors Structural Institutional fragility (weak governance, weak control of arms and drug trade) León state. In Nuevo León, the urban violence is dominated by the crimes against property, which is also account at least half of all offences in cities all over the world. It also seen that theft, vehi- cle robbery and murder are the fastest growing crimes in urban centers of the states. As it is discussed early in the ecological model, the urban violence in Nuevo León is mainly associated with the intra-individual inequality as well as inter-group in- equality, or relative deprivation of rural-to urban migrants com- pared to the rest of the city population. Studies indicate that both inter-individual and inter-group inequalities seem to mat- ter for lethal forms of urban violence. Thus, considering this it is important that policymakers should aim to facilitate more equitable access to basic social services among city dwellers. References Benard, B. (1996). Resilience research: A foundation for youth devel- opment. New Designs for Youth Development, 12, 14-18. Jamaica: Community Youth Development. Benjamin, J. A. (1996). AIDS prevention for refugees: The case of rwandans in Tanzania. Ai dscaptions, 3, 4-9. Blum, R. W., McNeely, C. A., & Reinhart, P. M. (2002). Improving the odds: The untapped power of schools to improve the health of teens. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Adolescent Health and Development. Brennan, E. (1999). Population, urbanization, environment, and secu- rity: A summary of the issues. Comparative Urban Studies Occa- sional Papers series, N umber 22. Brockerhoff, M., & Brennan, E. (1998). The poverty of cities in devel- oping regions. Population and development Review, 24, 75-114. doi:10.2307/2808123 Bourguignon, F. (1999). Crime, violence and inequitable development. The Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics, Washington D.C., 28-30 April 1999. Chiricos, T. (1987). Rates of crime and unemployment: An analysis of aggregate research evidence. Social Problems, 34, 187-211. doi:10.1525/sp.1987.34.2.03a00060 Dunst, C. (1993). Implications of risk and opportunity factors for as- sessment and intervention practices. Topics in Early Childhood Spe- cial Education, 13, 143-153. doi:10.1177/027112149301300204 Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, D., & Loayza, N. (1998). Determinants of crime rates in Latin America and the world: An empirical assessment. Washington, DC: World Bank. Fajnzylber P., Lederman D., & Loayza N. (2002). What causes crime and violence. European Econo mic Review, 46, 1323-1357. Garbarino, J. (2001). An ecological perspective on violence. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 361-378. doi:10.1002/jcop.1022 Garbarino, J (1995). Raising children in a socially toxic environment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Gurr, T. R. (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Hannerz, U. (1980), Exploring the city: Inquiries toward an urban anthropology. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. Horowitz, D. L. (1985). Ethnic groups in conflict. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. Huntington, S. P. (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. Kaufmann, C. (1996). Possible and impossible solutions to ethnic civil wars. International Security, 20, 136-175. Moser, C., & McIlwaine, C. (2004b). Drugs, alcohol and community tolerance: An urban ethnography from Colombia and Guatemala. Environment and Urbanization, 16, 49-62. Muller, E. N. (1988). Inequality, Repression, and violence: issues of theory and research design. American Sociological Review, 53, 799- 806. Penglase, R. B. (2005). The shutdown of Rio de Janeiro: The poetics of drug trafficker violence. Anthropology Today, 21, 3-6.  A. K. AC HARYA 182 doi:10.1111/j.0268-540X.2005.00379.x Posen, B. (1993). The security dilemma and ethnic conflict. Survival, 35, 27-47. Rodgers, D. (2006-a). Living in the shadow of death: Gangs, violence and social order in urban Nicaragua, 1996-2002. Journal of Latin American Studies, 38, 267-292. Rodgers, D. (2005-a). Youth gangs and the perverse livelihoods strate- gies in Nicaragua: Challenging certain preconceptions and shifting the focus of the analysis. The Arusha Conference on New Frontiers of Social Policy, Tanzania, 12-15 December. Rosenberg, M. L., Butchart, A., Mercy, J., Narasimhan, V., Waters, H., & Marshall, M. S. (2002). Clear turn off turn on interpersonal vio- lence - Disease control priorities in developing countries. Washing- ton DC: World Bank. Sameroff, A., Seifer, R., Barocas, R., Zax, M., & Greenspan, S. (1987). Intelligence quotient scores of 4-year-old children: Socio-envi- ronmental risk factors. Pediatrics, 79, 343-350. Search Institute (1998). Healthy communities healthy youth tool kit. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Search Institute Publisher. Thomas, S. (2008). Urbanization as a driver of change. The Arup Jour- nal, 1, 58-67. Winton, A. (2004). Urban violence: A guide to the literature. Environ- ment and Urbanization, 16, 165-184. Zaidi, S. A. (1999). Urban safety and crime prevention. UMP-Asia Occasional Paper No. 42.

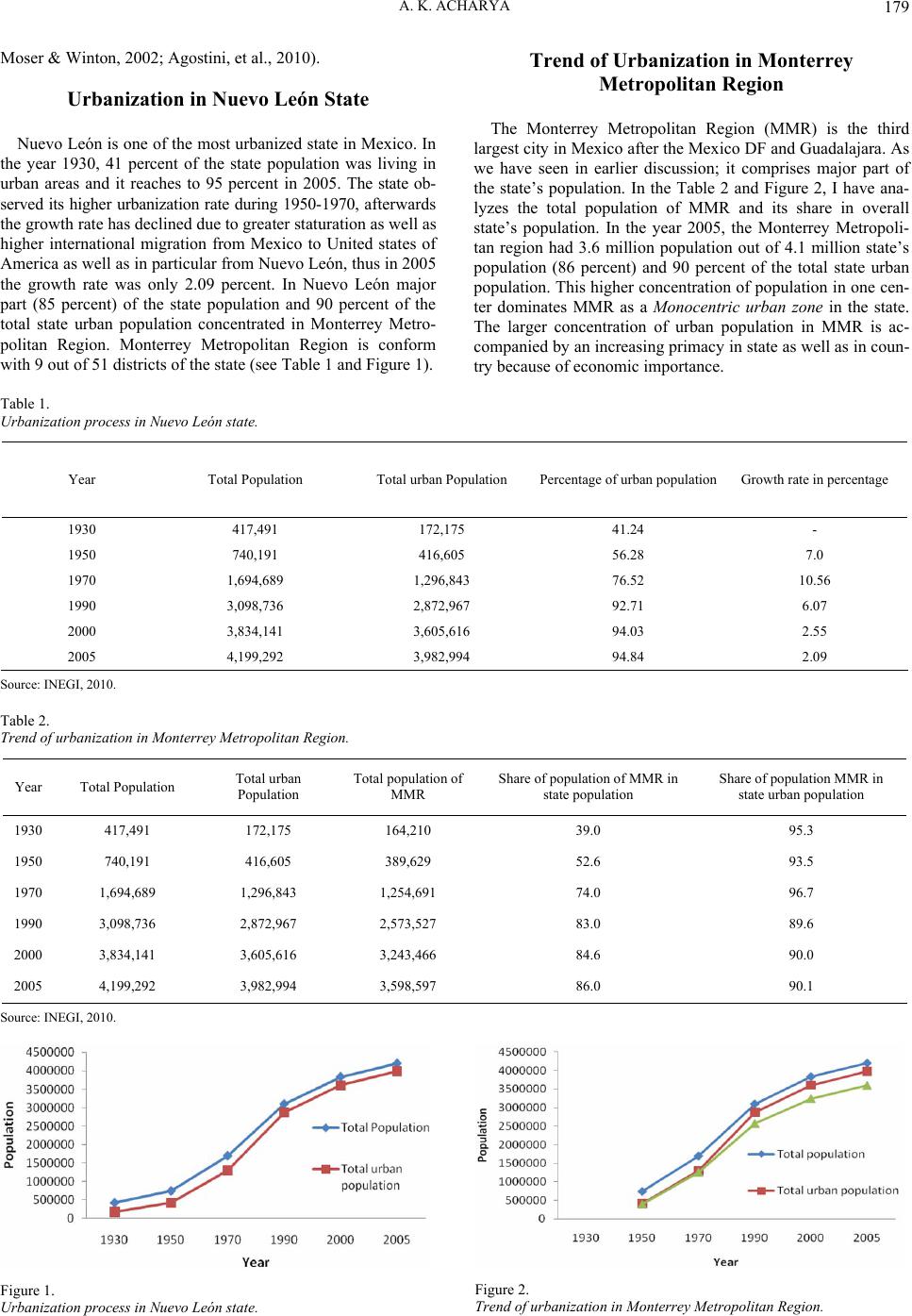

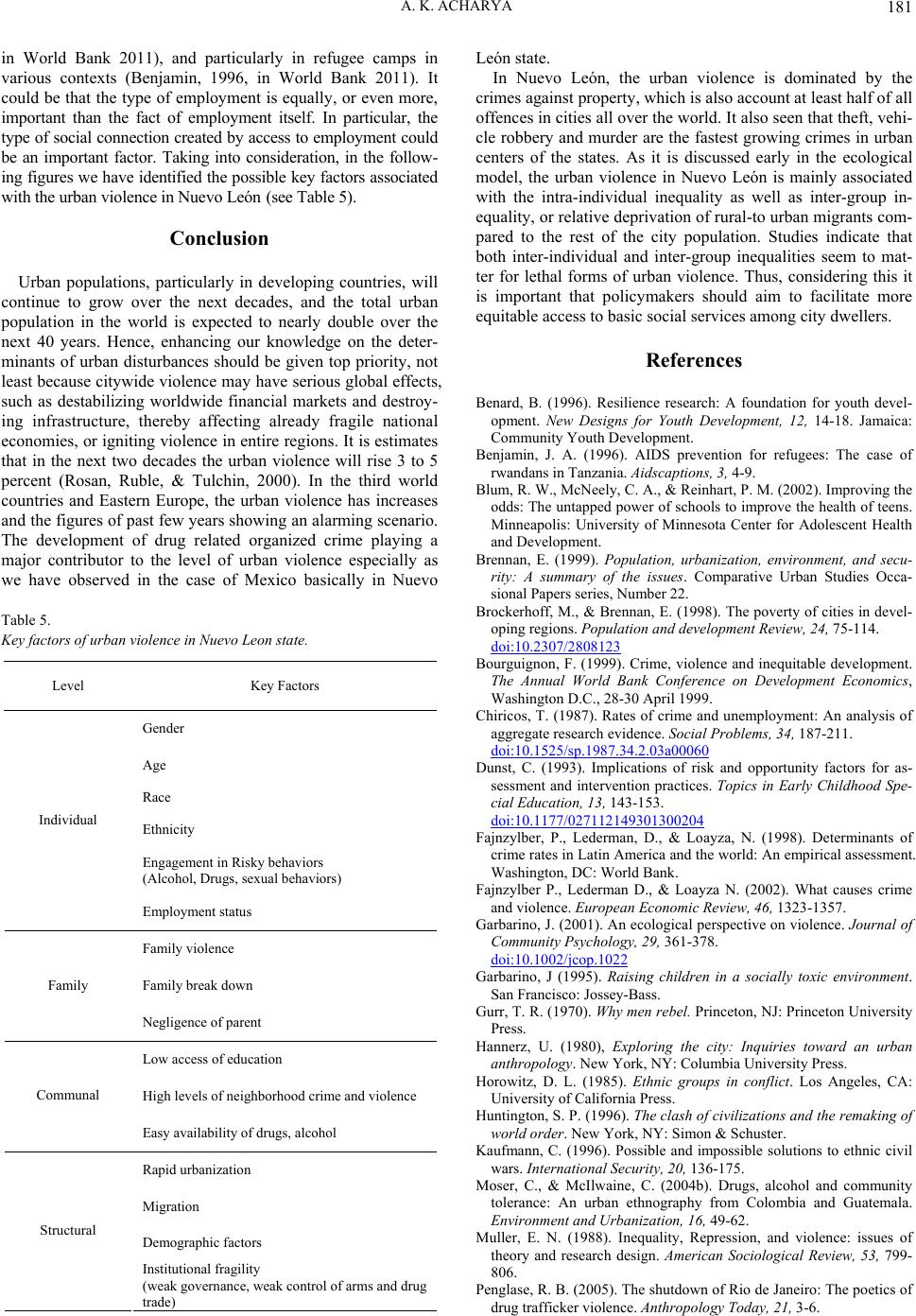

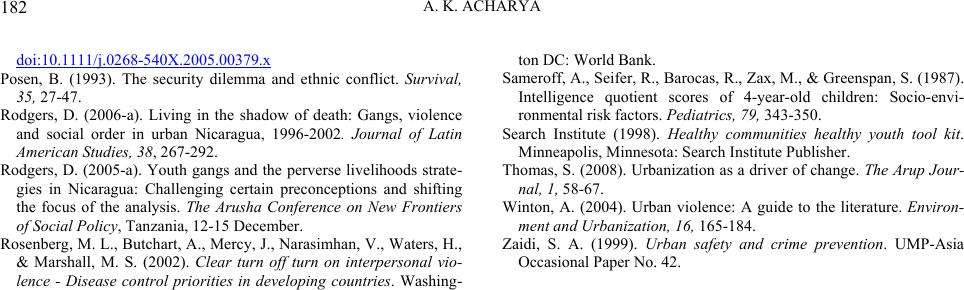

|