Journal of Service Science and Management, 2011, 4, 243-252 doi:10.4236/jssm.2011.43029 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 243 Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction Jung-Wan Lee, Samuel Mendlinger Department of Administrative Sciences, Boston University, Boston, USA. Email: {jwlee119, mendling}@bu.edu Received July 1st, 2011; revised August 6th, 2011; accepted August 17th, 2011. ABSTRACT This paper investigates the effect of perceived self-efficacy on perceptions of ease of use and usefulness of online learn- ing systems, and its effects on behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and student satisfaction. Eight hundred and seventy-two samples collected from students in online classes in the United States and Korea were ana- lyzed using factor analysis and structural equation modeling techniques. The results show that: 1) perceived self-effi- cacy serves as an antecedent to online learning acceptance and its degree of importance is partially a function of cul- tural background; and 2) perceived usefulness of online learning systems influences positively on online learning ac- ceptance and student satisfaction. Significant differences were found between Korean and US students but how much of this was due to cultural differences or degree of experience could not be determined. Keywords: Information Technology, Online Education, Cultural Difference 1. Introduction The Internet and information technology (IT) has been incorporated into educational platforms to expand learn- ing activities without depending on traditional face-to- face classes. The flexibility of time and place for learning may be the most important feature of online education. Educational institutions, including many quality colleges and universities, are using online classes to deliver course content over the Internet. O’Donoghue, Singh, and Dor- ward reported the merits of IT in classes [1]. Basile and D’Aquila assessed student attitudes toward the use of the Internet in classes [2] and Lawson reported positive ex- periences from students with online classes [3]. However, this educational platform has been criticized as being based on the assumption that most students have the abil- ity to use IT in the online educational setting [4]. It has been argued that online education tools may be unfamil- iar or difficult for many students, and this may result in many students not being enthusiastic about taking online courses [5,6]. Hong, Ridzuan and Kuek stated that in- formation technology skills are found to be an important aspect for students’ improvement in web-based courses [5]. Therefore it is still arguable that students should have basic computer skills and knowledge about IT be- fore taking online classes. In designing and delivering online classes, the degree of student perceptions and satisfaction should be impor- tant as higher education institutions often consider stu- dent satisfaction as one of the key factors in online edu- cation quality [7,8]. However, without knowing what predicts student satisfaction in online classes, it is diffi- cult to meet their needs and improve their learning out- comes. Therefore there is a need to better understand predictors that affect student satisfaction in online classes, including self-efficacy, technical skills and attitudes to- ward online learning and cultural differences that may affect these predictors. New challenges in online education are characterized by the increased focus on users’ characteristics and reac- tions and their changing needs. The problem is that peo- ple differ across regional, linguistic, and country bounda- ries and users’ requirements are strongly influenced by their local cultural perspective. The increasing use and acceptance of online learning puts forth the issue that such use and acceptance of online learning is a function of culture. Catering for cultural diversity seems impera- tive for the diffusion of online courses for international use. It has been claimed that the Internet and electronic commerce (e-commerce) originated in Western culture as the majority of Internet websites and e-commerce appli- cations have been developed in Western countries [9]. The same can be said for the use and acceptance of online learning. Subsequently, Western vs non-Western  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction 244 culture constitutes a set of parameters that may signifi- cantly influence online learning acceptance and satisfac- tion. In this regard, in order to better understand the diverse user populations and their preferences toward online learning acceptance, this study examines how perceived self-efficacy affects online learning acceptance and how perceived self-efficacy influences student satisfaction in online classes in two culturally different group of stu- dents: 1) Koreans who learn in a culture that is defined as group orientated or collectivism and thus more likely to work in a group; and 2) US students who learn in a cul- ture defined as individualism who are more likely to work alone. This difference, collectivism vs. individual- ism may affect a student’s sense of self-efficacy with individualistic cultures having students with high self- efficacy versus cultures that are more collective having students with a wider range of self-efficacy. Path analysis is used to determine the extent to which key elements explain online learning acceptance and student satisfac- tion in online classes. This paper will examine to what extent does perceived self-efficacy influence online learning acceptance and student satisfaction in collective vs. individualistic cultures? 2. Literature Review and Hypothesis 2.1. Online Education and Student Satisfaction Online education is the most widely used term to describe information technology based learning in all its forms, although “e-learning”, “distance learning” or “distance education”, and “online learning” have also been used. Rosenberg defined online education as delivering course content to the end-user via computer using Internet tech- nology [10]. This definition is endorsed by others who describe learning through a networked computer system using web-based software [11]. Studies on online educa- tion demonstrated its positive impact and potential on stu- dents due to its flexibility and convenience offered by online classes [12]. In this paper, online education is de- fined as a form of education facilitated by information technology, and promoted by the form of social learning that creates connectivity and interaction between instruc- tors and students. This paper will use the terms online education, online learning, and online classes interchange- ably. Student satisfaction and appreciation of online educa- tion was found in much literature [13]. The literature sup- ports that a higher level of computer experience is linked to greater satisfaction in online learning [14]. Liu et al. reported that the Internet-enabled and tangible user inter- face helped build students’ positive perception toward on- line learning [15]. Changchit reported that WebCT, mes- sage boards, and chat rooms were the most useful tools that were linked to greater satisfaction in online learning [16]. Hammoud, Love, Baldwin, and Chen reported that students often have a positive attitude toward WebCT, and the use of WebCT has a positive influence on students’ achievements and their outcomes [17]. 2.2. Self-Efficacy and Online Learning Acceptance General self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief that one has the ability to perform a particular behavior. Bandura defined self-efficacy as an individual’s judg- ment of the individual’s capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances [18]. He further stated that peo- ple’s beliefs in their efficacy influenced their choices, their aspirations, and how much effort they mobilized in a given endeavor. Self-efficacy should not be considered as a measure of a specific skill because it concerns the extent to which individuals believe they can perform by using their skills [19]. Thus, self-efficacy could be un- derstood as a key mechanism that accounts for the inter- active relationship between internal forces and external stimuli that affect human behavior. Individuals who per- ceive themselves as highly self-efficacious tend to initi- ate a sufficient effort that may produce successful out- comes, whereas those who perceive low self-efficacy are likely to cease their efforts prematurely and fail in the task. To the same extent, self-efficacy toward online learn- ing, which is a situation-specific form of efficacy, refers to individuals’ judgment of their capabilities to use online learning systems (including computers, the Inter- net, and web-based instructional and learning tools). Marakas, Yi, and Johnson pointed out that there is a dif- ference between task-specific and general self-efficacy [20]. Marakas et al. suggested that individuals who have high technology self-efficacy were more likely to report higher perceptions of usefulness and ease of use [20]. Even for users with general self-efficacy, there may be a lack of task-specific self-efficacy. Agarwal, Samba- murthy, and Stair found that technology self-efficacy affected the perceived ease of use toward new systems [21]. Therefore, it seems that familiarity with the tech- nology is important when taking an online course. Tech- nology can provide a better online learning experience by enhancing interaction between students and instructors. Once students become familiar with the technology, they should be more in favor of online learning. Inadequate or incomplete skills and knowledge inevitably compromises to poor quality of learning experiences. Students’ online class readiness and motivation are keys for success of any online program. Hence, students who use informa- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction245 tion technology in their personal and professional lives should be more comfortable and familiar with online learning environments. 2.3. Technology Acceptance and Student Satisfaction of Online Learning Based on the theory of reasoned action, the technology acceptance model (TAM) suggests that user acceptance of technology is driven by users’ beliefs about the con- sequences of that usage [22,23]. According to Davis, perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are the two main factors affecting users’ acceptance behaviors. Davis defined perceived ease of use as the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular sys- tem would be free from physical and mental efforts and defined perceived usefulness as the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular system will enhance his or her job performance. In particular, TAM predicts that users embrace new technology when their perceptions of the ease of use and the usefulness of the technology are positive. Adapting TAM to examine student satisfaction and technology adoption in online classes, Lin found that student intention to use technology affected their learning outcome in the online class environment [24]. Previous studies recognized that students’ familiarity with tech- nology usage and perceptions of how they are supported by online learning systems influenced student satisfac- tion [15-17]. Therefore, the technology acceptance be- havior of students may influence satisfaction with online learning because technology and communication tools play deterministic roles. 2.4. Culture and Online Learning Acceptance Culture refers to values, traits, beliefs, and behavioral patterns that may characterize a group of people. Hof- stede suggests that culture reflects a composite of human nature and personality (i.e., values and traits inherited or learned by individuals) [25]. Cross-cultural research has identified an array of cultural values including individu- alism/collectivism, power distance, time orientation, and uncertainty avoidance [25], in which that may affect stu- dent satisfaction when taking online courses. Societies and their culture differ in their emphasis on individual rights and obligation to society. Individualism/collec- tivism refers to the extent to which individuals’ emphasis and identity is centered on the self or the group. Indi- vidualism describes societies in which the ties between individuals are loose, such as the US, the UK, and Can- ada, and people are expected to both take greater initia- tive and work on their own. In collectivism, people are integrated into strong and cohesive groups that work to- ward a common goal, and tend to focus on the needs of the group over their personal needs, such as Korea, China, and Japan. Researchers have started to employ cultural parame- ters in their studies of online education. Srite, Thatcher, and Galy suggested that cultural values influence tech- nology acceptance and use [26], and specifically indi- vidualism/collectivism directly influences use of com- puter-based learning. Zaharias reported that participants from Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey where found to be statistically different in their attitudes toward several online learning dimensions including accessibil- ity, instructional feedback and learner guidance and sup- port [27]. Studies have examined both technology accep- tance and national culture [28,29]. Most studies in this field have employed Hofstede’s framework and cultural dimensions. Graff, Davies, and McNorton found indi- vidual differences in terms of attitudes toward computer- based learning and differences between UK and Chinese students [30]. Downey, Wentling, Wentling, and Wads- worth measured the relationship between national culture and the usability of an online learning system and re- ported that individuals from cultures with low power distance indicators rated the system’s usability higher than individuals from high power distance cultures [31]. It may be necessary for recognizing cultural difference in accepting online courses and understanding student sat- isfaction. 2.5. Research Framework and Hypotheses Building on the above arguments, it would be useful to understand how perceived self-efficacy (PSE) and cultural differences influence acceptance of online classes and student satisfaction. In addition, individualism/collecti- vism may influence perceptions of self-efficacy, accep- tance of online learning and student satisfaction. Accep- tance of online learning and satisfaction may also differ in individuals’ experience and confidence of their abilities and capabilities. It is likely that groups who score high on individualism are more likely to accept online learning and achieve better outcomes in online class activities as compared to their more collectivist groups. The research framework is developed in Figure 1. Accordingly this study proposes five hypotheses: H1: PSE will have a positive effect on perception of ease of use (PEOU) toward online learning; H2: PSE will have a positive effect on perception of usefulness (PU) toward online learning; H3: PSE will have a positive effect on behavioral in- tention to accept online learning and student satisfaction; H4: PEOU will have a positive effect on behavioral intention to accept online learning; H5: PU will have a positive effect on behavioral inten- ion to accept online learning. t Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 246 Figure 1. Research Framework and Structural Model 3. Research Methodology Table 1. Survey and sample characteristics. 3.1. Survey and Sample Characteristics Country Korea The US Number of respondents N = 582 N = 290 Sample characteristics Frequency (percentage) Frequency (percentage) Male 340 (58.4) 152 (52.4) Gender Female 242 (41.6) 138 (47.6) 23 - 29 310 (53.3) 151 (52.1) Age 30 - 39 272 (46.7) 139 (47.9) Secondary (high school) 160 (27.5) - Junior college 206 (35.4) - University 178 (30.6) 215 (74.1) Education Graduate 38 (6.5) 75 (25.9) A questionnaire was developed for determining student perceptions toward PSE, PEOU, PU, behavioral intention to accept online class and degrees of student satisfaction. Two surveys were conducted. The first survey examined students from a Korean university through a web-based survey method during spring 2009 semester (March-June 2009). Of approximately one thousand participants in the survey, five hundred eighty-two useful responses that were between 23 to 39 years old were chosen for in- depth analysis (Table 1). The second survey examined students from a US university through a web-based sur- vey during summer 2009 semester (May-July 2009). Of approximately four hundred participants in the survey, two hundred ninety useful responses that were between 23 and 39 years old were chosen for in-depth analysis. Though this study has employed the samples of compa- rable ages, the authors realize the weakness of examining undergraduates from one culture versus graduates from the other culture. More than 84% of the respondents had been enrolled at their university for one year or more. tions were used to measure student perceptions toward ease of use and usefulness of online classes. Those ques- tions were borrowed from the TAM model and modified for online education research. 3.2. Summary of Descriptive Statistics and Survey Questions To measure behavioral intention to accept online learning and satisfaction variables, this study used four survey questions: “intent to register for online classes,” “likelihood of recommending online classes”, “intent to continue taking online classes,” with including response options ranging from “least likely = 1” to “most likely = 5”, and “overall satisfaction with online classes”. Per- ceived self-efficacy was measured by using four survey questions developed by the authors. Nine survey ques- There were significant differences found between the Korean and the US students in their answers to the sur- vey questions (Table 2). While in 16 of the 17 questions the US students scored higher than the Korean students in satisfaction (p < 0.01, G-test), the results differed among categories. For perceived ease of use (PEOU) the difference was significant in only one question, PEOU3, “It is easy for me to become skillful at using the online learning system”. For perceived usefulness (PU), only  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction247 one question, PU5 “I find online learning system useful in my study completion” was significant. For behavioral intention to accept online learning, no significant dif- ferences were found. However for perceived self-efficacy (PSE), all four questions were very significant between the Korean and the US students with the US students scoring significantly higher. These results support the argument that more US stu- dents believe that they have the skills and learning ex- perience needed and are ready for online learning than Korean students. In fact the US students score statisti- cally higher in the PSE questions than in the others (ANOVA, 0.05 < p < 0.01). Interestingly, when asked if they would recommend the online learning as an ideal learning platform, the US students gave this question the lowest score and the Korean students the second lowest. It appears that even though US students show more con- fidence and are more ready to accept online learning than Korean students, both groups have reservations about online education. 3.3. Factor Analysis and Reliability Test Factor analysis with a varimax rotation procedure was employed to identify underlying predictors of behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and student satisfaction with online classes. Afterwards, a statistical reliability test was used to test internal consistency for the survey items. Factor analysis yielded three factors based on an eigenvalue cut-off of one (Table 3). The sums of squared loadings from the three factors, “per- ceived ease of use (PEOU)”, “perceived usefulness (PU)” and “perceived self-efficacy (PSE),” have the cumulative value of 81% in explaining the total variance of the data. To test the appropriateness of factor analysis, two measures were used. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) overall measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) was 0.946, which falls within the acceptable level, significance at p < 0.001. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 10160.774 (degree of freedom = 78), significance at p < 0.001, which showed a highly significant correlation among the survey questions. Further scale refinement was done by examining item-to-total correlation. This led to the reten- tion of 13 items, which represented the three components: PEOU (4 items, α = 0.893), PU (5 items, α = 0.940), and PSE (4 items, α = 0.926) (Table 3). The analysis of moment structures was used for an empirical test of the structural model [32]. The maximum likelihood estimation was applied to estimate numerical values for the components in the model. Confirmatory factor analysis was applied to test the validity of the Table 2. Summary of descriptive statistics and survey questions. Survey Questions (5-point scale) Mean of Korea Mean of The US PEOU: 1. I find it easy to use the online learning system to do what I want it to do 3.921 4.005 2. I find the online learning system is clear and understandable for me 3.957 3.879 3. It is easy for me to become skillful at using the online learning system 3.921 4.177* 4. I find the online learning system easy to use 4.008 4.094 PU: Using online learning system 1. enables me to accomplish programs more quickly. 3.723 3.941 2. improves my ability to accomplish academic tasks. 3.743 3.863 3. increases my productivity in accomplishing academic tasks. 3.729 3.903 4. enhances my effectiveness in accomplishing academic tasks 3.804 3.831 5. I find online learning system useful in my study completion. 3.767 4.185** PSE: 1. I have skills necessary to use the online learning system 3.726 4.552*** 2. I have Internet connection fast enough to use the online learning system 3.982 4.464*** 3. I have the knowledge necessary to use the online learning system 3.862 4.324*** 4. Overall, I am ready to use the online learning system 3.973 4.445*** Behavioral Intention to Online Learning and Satisfaction: 1. If I need to study for advanced degrees (programs), I would expect to use the online learning system 3.643 3.761 2. If asked, I would likely recommend the online learning system as an ideal learning platform 3.672 3.692 3. For future advanced degrees (programs/certificates), I would probably use the online learning system 3.703 3.817 4. Overall, I am satisfied with the online learning system 3.851 3.901 *0.05 < p < 0.01; **0.01 < p < 0.001; ***p < 0.001. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction 248 Table 3. Results of factor analysis for survey questions. Items Factor loadings Eigenvalue Extracted varianceComponent name Corrected item-total correlationα PEOU1 0.558 2.674 20.569 Ease of Use (PEOU) 0.635 0.893 PEOU2 0.667 0.812 PEOU3 0.717 0.824 PEOU4 0.723 0.796 PU1 0.804 4.327 33.288 Usefulness (PU) 0.804 0.940 PU2 0.824 0.846 PU3 0.849 0.858 PU4 0.872 0.859 PU5 0.779 0.820 PSE1 0.760 3.481 26.774 Self-efficacy (PSE) 0.788 0.926 PSE2 0.840 0.822 PSE3 0.873 0.862 PSE4 0.776 0.844 Total 80.631 The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy = 0.946. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, Chi-square = 10160.774, Significance p = 0.000. Extraction: Principal Component Analysis, Rotation: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. scales in measuring specific constructs of the measure- ment model. The degree of freedom with large standard error variances was evaluated to diagnose possible iden- tification problems. The identification problem was re- medied in accordance with Hayduk’s guidelines [33]. The criteria of Bollen were applied to evaluate the over- all goodness-of-fit of the proposed model [34]. Good- ness-of-fit measures were selectively assessed as follows: Chi-square statistic (CMIN), degrees of freedom (DF), CMIN divided by DF (CMIN/DF), root mean square residual (RMR), root mean square of approximation (RMSEA), goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted good- ness of fit index (AGFI), normed fit index (NFI), and parsimony ratio (PRATIO). 4. Results of Hypothesis Test The results of the data analysis generally achieved ac- ceptable goodness-of-fit measures (Table 4). The index of GFI (0.884) indicates that the fit of the proposed model is about 88% of the saturated model (the perfectly fitting model). The index of NFI (0.932) indicates that the fit of the proposed model is about 93% over the null model. Many fit measures represent an attempt to bal- ance between parsimonious and well fitting model, that is, two conflicting objectives―simplicity and goodness of fit [35]. This study prefers a simple and parsimonious model over complex one. Null hypothesis 1, “There is no relationship between PSE and PEOU” and null hypothesis 2, “There is no re- lationship between PSE and PU” were empirically tested by the data. The results showed that there are positive relationships between PSE and PEOU, and between PSE and PU, which are statistically significant (p < 0.001) at a 95% confidence level, for Korean and US students (Ta- ble 4). This suggests that perceived self-efficacy has a positive and significant effect on both perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of online classes. Null hypothesis 3. This study empirically tested the hypothesis “There is no relationship between PSE and behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction.” Korean students had a statistically sig- nificantly positive relationship (p < 0.05) at a 95% con- fidence level (Table 4). However, US students had no statistically significant positive relationship (p > 0.05) at a 95% confidence level. This suggests that perceived self-efficacy has different effects on behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction. Null hypothesis 4. This study empirically tested the hypothesis “There is no relationship between PEOU and behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction.” Korean students had no statistical sig- nificant positive relationship (p > 0.05) at a 95% confi- dence level (Table 4). However, US students had a sta- tistically significant positive relationship (p < 0.001) at a 95% confidence level. This suggests that perceived ease of use has different influences on behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction. Null hypothesis 5. This study empirically tested the hypothesis “There is no relationship between PU and behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction249 Table 4. Outputs of structural equation model (SEM) estimate. Path diagram Korean students (N = 582) US students (N = 290) Independent variables Dependent variables Estimate (S.E) Estimate (S.E.) H1: Perceived Self-efficacy Perceived ease of use 0.889 (0.033)*** 0.943 (0.077)*** H2: Perceived Self-efficacy Perceived usefulness 0.666 (0.037)*** 0.620 (0.072)*** H3: Perceived Self-efficacy Online learning acceptance and satisfaction0.246 (0.072)** 0.000 (0.085) H4: Perceived Ease of use Online learning acceptance and satisfaction0.014 (0.068) 0.389 (0.056)*** H5: Perceived Usefulness Online learning acceptance and satisfaction0.613 (0.034)*** 0.500 (0.058)*** **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 statistically significant at a 95% confidence level. Korean students: CMIN = 885.988, DF = 114, Probability level = 0.000, CMIN/DF = 8.341, RMR = 0.040, RMSEA = 0.051, GFI = 0.884, Adjusted GFI = 0.844, NFI = 0.932, PRATIO = 0.838. US students: CMIN = 659.833, DF = 114, Prob- ability level = 0.000, CMIN/DF = 4.868, RMR = 0.046, RMSEA = 0.054, GFI = 0.862, Adjusted GFI = 0.815, NFI = 0.883, PRATIO = 0.838. and satisfaction”. The result was a significant statistical positive relationship between PU and behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction (p < 0.001) at a 95% confidence level, for both Korean and US students (Table 4). This suggests that perceived usefulness has a positive and direct effect on behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction. Overall, the results of the hypothesis test suggest that: 1) Perceived self-efficacy can serve as a predictor of be- havioral intention toward online learning acceptance; and 2) Perceived usefulness has a positive and direct influ- ence on behavioral intention toward online learning ac- ceptance. However, the effects of perceived self-efficacy and perceived ease of use on behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction are different in the two groups, though the reasons may be cultural, degree of experience, academic degree or a combination of the three. 5. Discussions and Managerial Implica tions This study investigated the effect of perceived self-effi- cacy on perceptions of ease of use and usefulness toward online classes and its effect on behavioral intention to- ward online learning acceptance in Korea and the US The results showed: 1) there was a significant difference between Korean and US students, i.e. US students scored significantly higher in perception of self-efficacy than Korean students; 2) perceived self-efficacy was a sig- nificant predictor of online learning acceptance for both Korean and US students; and 3) perceived usefulness of online learning was a significant predictor of positive behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance for both Korean and US students. It appears that most students in the two countries, regardless of their differ- ences, feel that the acceptance of online learning would be useful and beneficial to them. On the other hand, the results showed that: 1) percei- ved self-efficacy was a significant predictor of positive behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction for Korean but not US students; and 2) perceived ease of use toward online learning systems was a significant predictor of positive behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction for US but not Korean students. It appears that Korean stu- dents, compared to US students, feel that self-efficacy motivates and promotes positive behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction, and the ease of use of online learning systems has an insig- nificant relation to behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction. For US students most had a high perception of self- efficacy and so this was not a useful predictor but per- ceived ease of use, especially survey question PEOU#3, was a better predictor. A predictor is only useful if there are significant differences among the group of students being tested. As Korean students, who are from a more collectivistic society than US students, are more de- pendent on their social group, their individual confidence level and their self-efficacy may be more varied than US students. On the other hand, US students, who have a high level of self-efficacy, feel that the ease of use of online learning systems, which may differ from one stu- dent to another, motivates and promotes their positive behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction. That is, US students feel that the diffi- culty level of learning how to use online learning systems is a major factor that influences their behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction. The results of this study show online learning self-ef- ficacy positively influences online learning acceptance. This means that students with higher self-efficacy (both Korean and US) are more likely to perceive online learning systems as easier to use and more useful. When students believe in their capability of taking online classes successfully, they perceive online learning sys- tems easier to use and more useful. This finding supports Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction 250 that task-specific (online learning) self-efficacy plays a significant role when an individual has to make a choice and behaves under uncertainty. Perceived self-efficacy has a strong positive impact on behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction. It is desirable that students deem online learning systems easy to use, and have control over the system. Therefore, it is recommended that online learn- ing system suppliers, adopting institutions and online education marketers should provide adequate training and information about online learning systems to stu- dents to build skills and increase confidence in taking online classes. In this regard, institutions and educators should devote resources to students to develop the skills and knowledge of online learning management systems. The instructor should make sure that students have basic computer skills and IT knowledge before taking online classes, so that the student will not be frustrated and dis- couraged by using tools and environments of online learning. If necessary, at the beginning of an online pro- gram, students who have a low level of online learning proficiency should be provided with a training program or an informative orientation to assure the student gain- ing computer and web-communication skills and knowl- edge required for online classes. This study highlights the critical role of self-efficacy in perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of online learning systems. The findings clearly show that as long as students have the skills and knowledge to use online learning systems, they perceive online education is a use- ful learning format and an easy way of learning. Students will be more likely to enjoy online classes; if they believe in they have a reasonable level of competence to use online learning systems. While self-efficacy has been in- troduced and utilized in studies in information systems and social sciences, it is the first attempt to anchor perceived self-efficacy in the domain of online education. Due to the limitation of the data, i.e. comparing un- dergraduate Korean students with graduate US students, people must be careful in interpretation these results as differences could be due to cultural differences between the two groups; US students are more used to working and solving problems on their own than Korean students may be more attuned to the needs of the online platform than Korean students. The authors believe that much of these results support this conclusion (see PSE questions). However, the result cannot rule out that some of these differences may be due to the US students being graduate students and thus more experienced both in education (having had more courses and learned how to manage their educational needs) and possibly in the work force. This study tried to overcome this limitation by having both groups of students at about the same age. 6. Conclusions and Research Limitations The results showed: 1) the positive relationship between perceived self-efficacy and perceptions of ease of use and usefulness toward online learning systems; and 2) the positive relationship between perceived usefulness of online learning systems and behavioral intention toward online learning acceptance and satisfaction. Although limited, this study provides empirical evidence that cul- tural dimensions may influence online learning accep- tance and satisfaction due to its different approaches and characteristics. The finding suggests that many aspects of broadly defined culture influence situation-specific per- ceptions and behaviors. In light of the findings, the authors suggest that future research should examine additional cultural values and/or many cultures as potential sources of variation in online learning acceptance and satisfaction. This effort provides a series of hypotheses that integrate cultural dimensions into an extended online learning acceptance model. This integration is particularly relevant given the growing importance of global information communication tech- nologies (ICT), such as the Internet, Wi-Fi, and the fourth generation of cellular wireless communication networks, across several countries and cultures. There are still some personal variables (e.g., experi- ence using ICT and academic levels) and course vari- ables (course content, instructional designs, and instruc- tor experience) not addressed by this study. Addressing these limitations should increase the generalization of the findings to online learning formats. REFERENCES [1] J. O’Donoghue, G. Singh and L. Dorward, “Virtual Education in Universities: A Technological Imperative,” British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 32, No. 5, 2001, pp. 511-523. [2] A. Basile and J. M. D’Aquila, “An Experimental Analysis of Computer-Mediated Instruction and Student Attitudes in Principles of Financial Accounting Course,” Journal of Education for Business, Vol. 77, No. 3, 2002, pp. 137-143. doi:10.1080/08832320209599062 [3] T. J. Lawson, “Teaching a Social Psychology Course on the Web,” Teaching of Psychology, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2000, pp. 285-289. doi:10.1207/S15328023TOP2704_07 [4] P. Jones, G. Packham, C. Miller and A. Jones, “An Initial Evaluation of Student Withdrawals within an e-Learning Environment: The Case of e-College Wales,” Electronic Journal on e-Learning, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2004, pp. 113-120. [5] K. Hong, A. A. Ridzuan and M. Kuek, “Students’ Attitudes Toward the Use of the Internet for Learning: A Study at a University in Malaysia,” Educational Techno- logy & Society, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2003, pp. 45-49. [6] K. Xie, T. K. Debacker and C. Ferguson, “Extending the Traditional Classroom through Online Discussion: The Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction251 Role of Student Motivation,” Journal of Educational Computing Research, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2006, pp. 67-89. doi:10.2190/7BAK-EGAH-3MH1-K7C6 [7] M. G. Moore and G. Kearsley, “Distance Education: A Systems View,” 2nd Edition, Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont, 2005. [8] V. Roach and L. Lemasters, “Satisfaction with Online Learning: A Comparative Descriptive Study,” Journal of Interactive Online Learning, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2006, pp. 317-332. [9] S. J. Simon, “The Impact of Culture and Gender on Web Sites: An Empirical Study,” The Data Base for Advances in Information Systems, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2001, pp. 18-37. [10] M. J. Rosenberg, “E-Learning: Strategies for Delivering Knowledge in the Digital Age,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001. [11] E. McFadzean and J. McKenzie, “Facilitating Virtual Learning Groups: A Practical Approach,” Journal of Mana- gement Development, Vol. 20, No. 6, 2001, pp. 470-494. doi:10.1108/02621710110399774 [12] M. Allen, J. Bourhis, N. Burrell and E. Marbry, “Com- paring Student Satisfaction with Distance Education to Traditional Classrooms in Higher Education: A Meta- Analysis,” US Journal of Distance Education, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2002, pp. 83-97. doi:10.1207/S15389286AJDE1602_3 [13] K. Hong, K. Lai and D. Holton, “Students’ Satisfaction and Perceived Learning with a Web-Based Course,” Educational Technology and Society, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2003, pp. 116-124. [14] T. J. F. Mitchell, S. Y. Chen and R. D. Macredie, “The Relationship between Web Enjoyment and Student Perceptions and Learning Using a Web-Based Tutorial,” Learning, Media and Technology, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2005, pp. 27-40. doi:10.1080/13581650500075546 [15] W. Liu, K. S. Teh, R. Peiris, Y. S. Choi, A. D. Cheok, C. L. Mei-Ling, Y. L. Theng, T. H. D. Nguyen, T. C. T. Qui and A. V. Vasilakos, “Internet-Enabled User Interfaces for Distance Learning,” International Journal of Techno- logy and Human Interaction, Vol. 5, No.1, 2009, pp. 51-77. doi:10.4018/jthi.2009010105 [16] C. Changchit, “An Exploratory Study on Students’ Perceptions of Technology Used in Distance Learning Environment,” Review of Business Research, Vol. 7, No. 4, 2007, pp. 31-35. [17] L. Hammoud, S. Love, L. Baldwin and S. Y. Chen, “Evaluating WebCT Use in Relation to Students’ Attitude and Performance,” International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2008, pp. 26-43. doi:10.4018/jicte.2008040103 [18] A. Bandura, “Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control,” Freeman Press, New York, 1997. [19] M. Eastin and R. LaRose, “Internet Self-Efficacy and the Psychology of the Digital Divide,” Journal of Computer- Mediated Communication, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2000. http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol6/issue1/eastin.html [20] G. Marakas, M. Yi and R. Johnson, “The Multilevel and Multifaceted Character of Computer Self-Efficacy: To- ward Clarification of the Construct and an Integrative Framework for Reason,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1998, pp. 126-163. doi:10.1287/isre.9.2.126 [21] R. Agarwal, V. Sambamurthy and R. Stair, “The Evolving Relationship between General and Special Computer Self-Efficacy—An Empirical Assessment,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2000, pp. 418-430. doi:10.1287/isre.11.4.418.11876 [22] F. D. Davis, “Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 3, 1989, pp. 319-340. doi:10.2307/249008 [23] F. D. Davis, R. P. Bagozzi and P. R. Warshaw, “User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models,” Management Science, Vol. 35, No. 8, 1989, pp. 982-1003. doi:10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982 [24] Y. Lin, “Understanding Students’ Technology Appropria- tion and Learning Perceptions in Online Learning En- vironments,” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Univer- sity of Missouri, Columbia, 2005. [25] G. Hofstede, “Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 1991. [26] M. Srite, J. B. Thatcher and E. Galy, “Does within-Culture Variation Matter? An Empirical Study of Computer Usa- ge,” Journal of Global Information Management, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2008, pp. 1-25. doi:10.4018/jgim.2008010101 [27] P. Zaharias, “Cross Cultural Differences in Perceptions of e-Learning Usability: An Empirical Investigation,” Inter- national Journal of Technology and Human Interaction, Vol. 4, No.3, 2008, pp. 1-26. [28] M. Gallivan and M. Srite, “Information Technology and Culture: Identifying Fragmentary and Holistic Perspec- tives of Culture,” Information & Organization, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2005, pp. 295-338. [29] M. Srite and E. Karahanna, “The Role of Espoused National Cultural Values in Technology Acceptance,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2006, pp. 1-26. [30] M. Graff, J. Davies and M. McNorton, “Cross-Cultural Differences in Computer Use, Computer Attitudes, and Cognitive Style between UK and Chinese Students,” In: G. Richards, Ed., Proceedings of World Conference on E- Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education, Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), Chesapeake, 2003, pp. 1893- 1900. [31] S. Downey, R. M. Wentling, T. Wentling and A. Wads- worth, “The Relationship between National Culture and the usability of an e-Learning System,” Human Resour- ce Development International, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2005, pp. 47-64. doi:10.1080/1367886042000338245 [32] J. L. Arbuckle, “AMOS (version 6.0),” Small Waters, Chicago, 2006. [33] L. A. Hayduk, “Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL: Essentials and Advances,” Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1987. [34] K. A. Bollen, “Structural Equations with Latent Variables,” Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Effect on Online Learning Acceptance and Student Satisfaction Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 252 Wiley, New York, 1989. [35] J. H. Steiger, “Structural Model Evaluation and Modifica- tion: An Interval Estimation Approach,” Multivariate Behavioral Research, Vol. 25, No. 2, 1990, pp. 173-180. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4

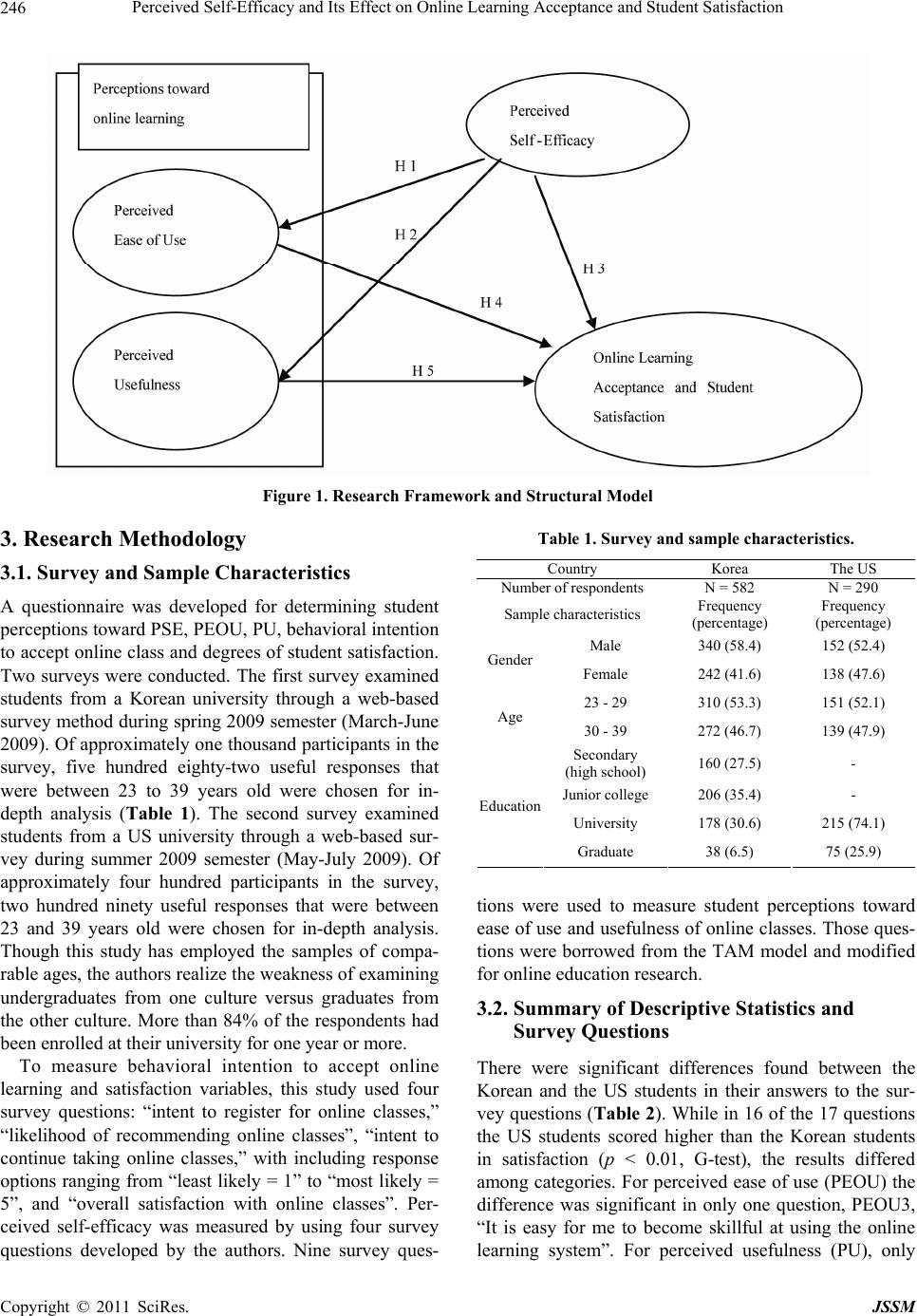

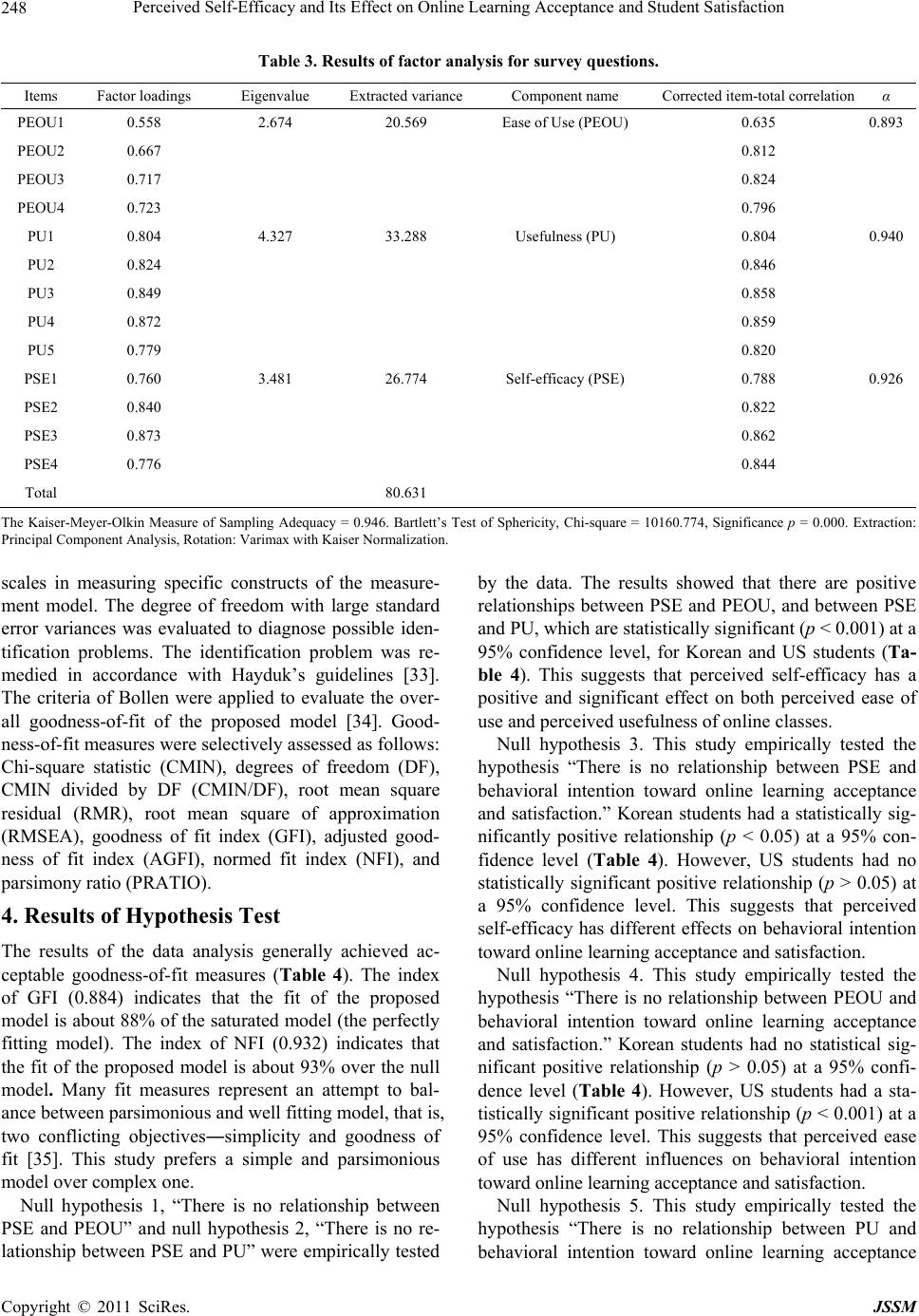

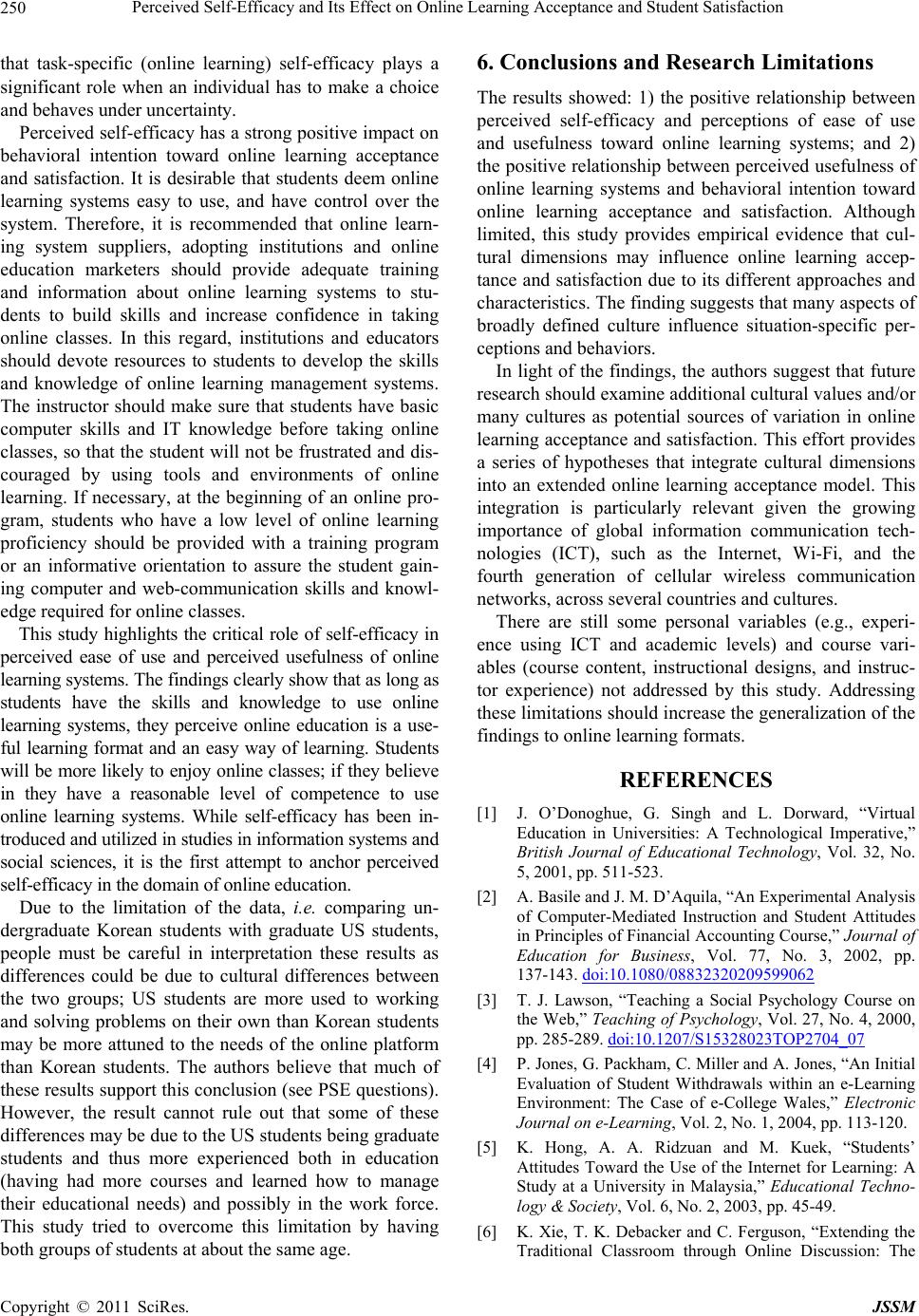

|