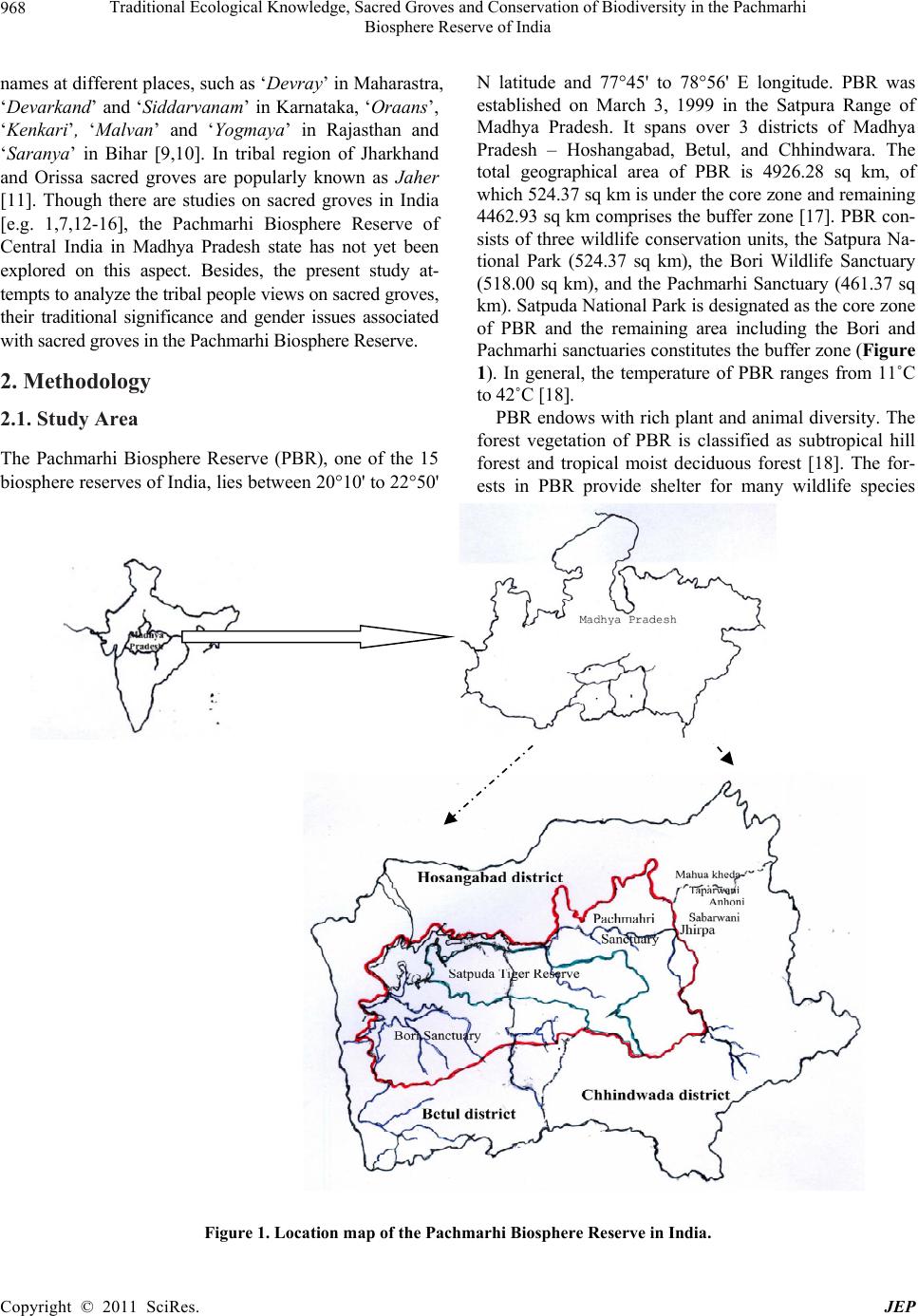

Journal of Environmental Protection, 2011, 2, 967-973 doi:10.4236/jep.2011.27111 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jep) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 967 Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Sacred Groves and Conservation of Biodiversity in the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve of India Chandra Prakash Kala Ecosystem & Environment Management, Indian Institute of Forest Management, Bhopal, India. Email: cpkala@yahoo.co.uk Received March 21th, 2011; revised July 19th, 2011; accepted August 23th, 2011. ABSTRACT The sacred groves in the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve (PBR) of India were studied to understand th e concep t of tradi- tional ecological and biodiversity conservation systems. A questionnaire survey was conducted in the selected villages of the PBR along with the survey of sacred groves. In 10 selected villages of the PBR 7 sacred groves were managed by Mawasi and 16 sacred groves b y Gond tribal communities. Differen t deities were worshipped in the sacred groves and each grove was named after the deity dwellin g in the respective sacred grove. A total of 19 such deities were recorded during the survey worshipped by the local people. In study area, various traditional customs associated with sacred groves were in practice. The sacred groves were rich in plant genetic diversity and were composed of many ethno- botanically useful species, including wild edible fruits, medicinal plants, fodder, fuelwood and timber yielding species. Given the importance of co nservation of biodiversity and ecos ystem attempts shou ld be made to maintain the sanctity o f sacred groves. Keywords: Sacred Grove, Biosphere Reserve , Biodiversity Conservation, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Gond & Mawasi Tribe 1. Introduction The indigenous communities still practice some cultural linkages between social and biophysical ecosystems. They have not only co-ev olved wi th the sur roundi ng envi ronm ental conditions but also they h ave mai ntai ned i t in a di vers e and productive state on the basis of traditional practices and beliefs [1,2]. The necessity of natural resources for hu man survival had made them to evolve a system having some customary laws and practices, which in long run might help to conserve the surrounding natural resources. Religion, being a powerful instrument for convincing people, has always been used for meeting the desired objectives of the society. The various relig ious philosophies have contributed significantly in the conserva tion of forests, biodiversity and landscapes by promulgating customary norms, practices and beliefs. However, wi th the advent of commercial interests in the forests and biodiversity, in most parts of the world, the indigenous philosophy and practices including religious approach adopted by the local comm unities for conservation of biodiversity have generally overlooked [3]. Weakening of traditionally inherited conservation practices and dominance of commercial interests over the period of time have invited several irregularities and concerns in the conservation and managem ent of natu ral res ourc es. Fortunately, some prominent live examples of traditional forms of biodiversity conservation still exit and in practice, which include the philosophy of sacred groves, sacred species and sacred landscape. The evidences suggest that sacred grove concept of biodiversity conservation had adopted by various indigenous communities worldwide, such as, aboriginals of Australia, Caucasus Mountains community, ancient Slavic people, German tribes [4], Greek and Romans, Kikuyu of Africa [5], and Mbeere tribe of East Africa [6]. Before the spread of Christianity and Islam the sacred groves covered much of the Middle East and Europe. The sacred grove concept is still relevant and exists today, especially in many parts of Asia, Africa and Mexico [7]. In India, over 13,720 sacred groves have been enlisted [8] that ex ist across diverse topography and climatic conditions from down south to north however, the actual number is thought to be much larger than that [2]. The sacred groves, in India, are known by different  Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Sacred Groves and Conservation of Biodiversity in the Pachmarhi 968 Biosphere Reserve of India names at different places, such as ‘Devray’ in Maharastra, ‘Devarkand’ and ‘Siddarvanam’ in Karnataka, ‘Oraans’, ‘Kenkari’, ‘Malvan’ and ‘Yogmaya’ in Rajasthan and ‘Saranya’ in Bihar [9,10]. In tribal region of Jharkhand and Orissa sacred groves are popularly known as Jaher [11]. Though there are studies on sacred groves in India [e.g. 1,7,12-16], the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve of Central India in Madhya Pradesh state has not yet been explored on this aspect. Besides, the present study at- tempts to an aly ze the trib a l people views on sacred groves, their traditional significance and gender issues associated with sacred groves in the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve. 2. Methodology 2.1. Study Area The Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve (PBR), one of the 15 biosphere reserves of India, lies between 20°10' to 22°50' N latitude and 77°45' to 78°56' E longitude. PBR was established on March 3, 1999 in the Satpura Range of Madhya Pradesh. It spans over 3 districts of Madhya Pradesh – Hoshangabad, Betul, and Chhindwara. The total geographical area of PBR is 4926.28 sq km, of which 524.37 sq km is under the core zone and remaining 4462.93 sq km comprises the buffer zone [17]. PBR con- sists of three wildlife conservation units, the Satpura Na- tional Park (524.37 sq km), the Bori Wildlife Sanctuary (518.00 sq km), and the Pachmarhi Sanctuary (461.37 sq km). Satpuda National Park is designated as the core zone of PBR and the remaining area including the Bori and Pachmarhi sanctuaries constitutes the buffer zone (Figure 1). In general, the temperature of PBR ranges from 11˚C to 42˚C [18]. PBR endows with rich plant and animal diversity. The forest vegetation of PBR is classified as subtropical hill forest and tropical moist deciduous forest [18]. The for- ests in PBR provide shelter for many wildlife species Figure 1. Location map of the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve in India. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Sacred Groves and Conservation of Biodiversity in the Pachmarhi 969 Biosphere Reserve of India including tiger, leopard, wild boar, barking deer, guars, cheetal, and Rhesus macaque. PBR is equally known for its cultural diversity, as it is inhabited by number of tribal and non-tribal communities. The major tribal group was Gond in the study area. Because of the numerical strength, the Gond tribe dom inates the central p arts of Indi a and the Central Province was known as Gondwana state, as the Gond ruled this part of India in the past [19]. The social or ga ni z at io n o f t h e G on d r ev ea ls th a t t h ey ar e d i vid e d i nt o clans, such as, Arpanche, Bariba, Dhurwe, Erpachi, Imne, Kakoria, Karskoley, Naure, Padram, Sarbeyan, Sarada, Sivarsaran, Vallabey, Barkare, Barkey, Batti, Eke, Kumre, Porta, Tekam and Wike. 2.2 Survey Methods For the study of sacred groves, the villages in buffer zone areas of PBR, close to the boundary of Satpuda Tiger Reserve, were surveyed. A total of 10 villages in buffer zone of PBR namely Sawarwani, Shahwan, Fatepur, Singhpur, Anhoni, Bandi, Deokoh Bodalkachhar, Khara and Taperwani were selected for intensive study of sa- cred groves and associated traditional biodiversity con- servation knowledge. The selected villages were domi- nated by tribal communities, mostly Gond and Mawasi with their offshoots (Table 1). The door to door ques- tionnaire survey was conducted in the selected villages of PBR. In most of the villages, generally the male mem- bers were available for interviews, however, female were also cooperated during the interview. Through questionnaire survey the information was collected on the name of sacred grove, its locality, size of grove, occurrence of plants in the sacred grove site, dei- ties worshipped, history or folklores and gender issues associated with such groves. Besides, the local people were encouraged to give their views and perceptions on the sacred grove with respect to the cultural, ecological, economical and conservation perspectives. During the field work, the sacred grove sites were also visited with the local knowledgeable people for preparing the list of species and associated knowledge with such sacred groves. Participant observations were also employed and information was collected by participating in various cultural activities of the local tribal peop le. 3. Results 3.1. Sacred Grove—Traditions and Values The study reveals the occurrence of 7 and 16 sacred groves in the study villages of the PBR managed by the Maw asi and Gond tribe, respectively (Table 2). The name of grove was given on the name of deity worshipped in the groves. A total of 19 such deities were recorded during the survey worshipped by the local people. The deities wor- shipped in the sacred groves may also differ across the different tribal groups and their sacred groves. There were some common deities of both Gond and Mawasi tribes, such as, Khedapati, Hardula and Budha Deo. Most of the groves were located outside the villages however some were very close to the village boundary. The average age of grove was between 150 to 200 years, as reported by the local people. The maximum size of sacred grove in the study villages was about 0.60 hectare. The Gond and Mawasi were so keen in the sacred grove concept that still today they used to establish and earmark some areas close to newly established human settlement in case of their rehabilitation from the core zone to the buffer zone areas of the PBR. The Khedapati grove of Khamda village in PBR was one such example in which the grove was reported to establish about 35 years ago with the establishment of the village due to construction of Tawa Reservoir and subsequent rehabili- tation of villagers in the buffer zone of the PBR. The villagers retained the village name – Khamda at the new site including the culture and traditions associated with biodiversity, ecosystem and environment. In view of this they selected a site and some plant species as the abode Table 1. Profile of the major study villages. Villages Total Household Total Population Communities Sawarwani 82 683 Gond, Yadav and Schedule Caste Shahwan 56 263 Gond, Ray and Vishwakarma Fatehpur 27 290 Gond Singhpur 210 1200 Gond, Mawasi, Yadav and Ray Anhoni 120 775 Gond and Yadav Bandi 35 500 Gond and Karar Patel Deokoh 30 352 Gond Bodalkachhar 40 289 Gond Khara 105 820 Gond Taperwani 48 362 Gond Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Sacred Groves and Conservation of Biodiversity in the Pachmarhi 970 Biosphere Reserve of India Table 2. Status of sacred groves in the studied villages of the PBR. Communities Name of the Groves Deities Wor- shipped Plants Symbolized as Abode of DeitiesAge of the Grove (Ap- proximate) Grove size (Approxi- mate) Khedapati Khedapati Madhuca indica, Zizyphus jujuba, Sho- rea robusta Dendrocalamus strictus, Ficus religiosa 200 0.60 hectare Sidhmaraj Hardula baba Tamarindus indica, Shorea robusta, Ficus benghalensis, Madhuca indica 150 Few trees Doval Deo Budhadeo Shorea robusta, Madhuca indica, Hard- wickia binata Dendrocalamus strictus, Ficus religeosa, Solanum nigrum, Tamarindus indica 150 0.40 hectare Dongardeo Dongarbuda Shorea robusta, Madhuca indica, Ter- minalia bellirica 200 0.20 hectare Maile Devi Meile Madhuca indica 150 - 200 Hardula/ Kunwar Deo Hardula Madhuca indica 200 Few trees Mawasi Bari Mata Bariyam Devi Madhuca indica, Shorea robusta 150 - 200 Few trees Khedapati Khedapati Shorea robusta, Madhuca indica, Ficus religiosa, Dendrocalamus strictus, Ter- minalia bellirica, Ficus benghalensis, Mucuna pruriens Phyllanthus sylves- tris, Phyllanthus officinalis, Buchanania lanzan 200 - 250 0.20 hectare Bagh Deo Bagh Deo Madhuca indica Not known Few trees Budha Deo Budha Deo Shorea robusta, Dendrocalamus strictus, Ficus religiosa, Butea monosperma, Madhuca indica, Ficus benghalensis , Aegle marmelos Not known 0.10 hectare Sayenebuda Sayenebuda Ficus benghalensis, Madhuca indica, Butea monosperma, Buchanania lanzan 150 Few trees Bari mata Bari mata Madhuca indica, Shorea robusta 150 Few trees Sidhbaba Sidhbaba Tamarindus indica Not known Few trees Bajranj Bajranj Madhuca indica, Tamarindus indica, Azadirachta indica, Anogeissus pendula, Hardwickia binata 200 - 300 Few trees Hardula Hardula Madhuca indica, Shorea robusta, Hard- wickia binata, Butea monosperma 150 0.10 hectare Gowal baba Gowal baba Phyllanthus officinalis 150 - 200 Few trees Kuripan Kuripan Shorea robusta, Madhuca indica 200 Few trees Dhobal Deo Dhobal Deo Madhuca indica 150 - 200 Few trees Balkhan Balkhan Shorea robusta 150 - 200 Siddha Baba (water god) Siddha Baba (water god) Ficus benghalensis , Shorea robusta, Terminalia bellirica, Hardwickia binata, Butea monosperma, Calotropis gigantea, Madhuca indica Not known 0.20 hectare Nagdeo Nagdeo Phyllantus officinalis, Madhuca indica Not known 0.20 hectare Gowalbaba Gowalbaba Madhuca indica, Terminalia chebula, Semecarpus anacardium Not known 0.10 hectare Gond Matabai Matabai Azadirachta indica, Ficus religiosa, Semecarpus anacardium Not known 0.10 hectare of some local deities to continue their tradition. The vil- lagers who were mainly Gond used to pay high respect to Mahuwa (Madhuca indica), as an important tree species not only for its multipurpose fruit giving nature but they used to worship the Goddess Khedapati in Madhuca in- dica in their former village. The sacred groves were rich in plant genetic diversity. These groves were composed of many ethnobotanically useful species, including wild edible fruits, medicinal plants, fodder, fuelwood and timber yielding species. Of Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Sacred Groves and Conservation of Biodiversity in the Pachmarhi 971 Biosphere Reserve of India the total plant species documented from the sacred groves, the fruits of many species were used as food and also for performing various religious functions. The most important fruit yielding plants was Madhuca indica, fol- lowed by Buchanania lanzan, Ficus benghalensis and Ficus religiosa. The local people used to collect these fruits mainly for their own consumption, and sometime depending upon the quantity of collection they used to sell the produces in the local market. The Gond and Mawasi used to prepare local liquor from the flowers of Madhuca indica. People also used to collect plants for curing dis- eases from the sacred grove site. In some cases before col- lection of such medicinal plant species, they offered a co- conut fruit and local liquor m ade of Madhuca indica. The villagers also disclosed the fact th at the soil in the sacred grove site remained more fertile than the adjacent sites of the village. This was possible due to high bio- mass and accumulation of high organic contents in such sites and further decomposition and nutrients release in such ecosystems. The farmers, who had agriculture land in the proximity of such sacred grove, had reported rela- tively higher productio n of grains in such lands. Besides, such farmers had noticed the higher moisture contents in their land. The local people also reported that sacred grove used to provide the shelter and food for many wildlife species including varieties of birds and butter- flies. Traditionally, some gender issues were associated with the sacred groves, especially with respect to the collec- tion and use of resources. There were some specific pe- riods in which the people were not allowed to enter the sacred groves. Before entering the sacred grove women were advised to take bath. During monthly menstruation women were strictly prohibited going inside the sacred groves, as there was a strong belief that it might defiled her or the deities living in the sacred grove. Similarly, the members from the deceased family were not allowed to enter the sacred grove sites until the completion of puri- fying rituals. The villagers generally performed the puri- fying ritual at 10th days of the death of the person. People strictly followed these customary norms in view of their own welfare as well as their deities and society. 3.2. Traditional Management of Groves The villagers themselves maintained the sacred groves with a great passion and sanctity. The traditional institu- tional mechanisms have been helping the local people in maintaining the sacred groves. The ‘padihar’ (saman) has given the responsibility to take care and worship the vil- lage deity in sacred groves (Figure 2). The local people were allowed to enter and worship the village deities in sacred grove. Mostly the head of the village or Padihar Figure 2. Worshipping deity in the sacred grove by Padiyar. collected the fruits from the sacred grove, particularly Madhuca indica and Tamarindus indica. There were some customs and cultural practices associated with col- lection and generally there was no restriction on the col- lection of fruits, however the local people were afraid of collection from the sacred groves. There was a general belief that since sacred groves were pure, the gatherers might be pun ished by spirits and deities for unauthorized collection of natural resources, though all deities were not considered unsafe. People always feared to go inside the sacred grove of Khedapati, as Khedapati was ac- knowledged the supreme deity of the tribal communities living in PBR. A belief was also associated with the old tree species that old trees in sacred grove generally the haunt of evil spirits, and as old as the tree, greater the chances of evil spirits to inh abit. The local people feared to go to such places, even in the noon and evening. Chil- dren and pregnant women were not allowed to visit such places. During present investigations, in 3 sacred groves, Bauhinia vahlii, an important ethnobotanical species was found. Leaf of Bauhinia vahlii was used for making cups Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Sacred Groves and Conservation of Biodiversity in the Pachmarhi 972 Biosphere Reserve of India and plates and the stem was used for making rope, none- theless the individuals of this species growing in the sa- cred grove were not exploited for such purposes by the villagers. Besides, there was no provision of cutting the plant species from the sacred grove. In case of not fol- lowing such customary norms, the lawbreaker was im- posed monetary penalty by the village council. 4. Discussion Gond being a dominant tribal community in the central India has enjoyed several benefits from the nature and thus has determined the uses of natural resources from historical past. Simultaneously, they have evolved strate- gies for the conservation of such useful and valuable biodiversity in view of their sustained av ailability. Gond s believe in many gods and goddess and some of the Gond deities are similar to the Hindus. Budha Deo is one of the most venerated deities of Gonds. They also worship oth er deities such as Bari Mata, Khedapati, Sidhbaba, Gowal baba, Bajrang, Bagh Deo, Nagdeo and Sayenebuda. The philosophy of worshipping deities in sacred groves, as practices by Gonds, is similar to many other tribal com- munities living in various parts of India [12,20]. Ay- yappa, Aiyanar and Sasta in Southern India are the dei- ties of woods, who used to guard the villagers and drive away their enemies [6,21]. The religious persons in Gond are Padiar (shaman) and Bhomka (priest), who enjoy a high respect in the community. Gond and Mawasi have their own calendar, which they use for different purposes including collection of forest resources, cultivation of crops and performing various relig ious activities. The fear of Gods and Goddess in the community might have been used as an instrument by the Padiar and Bhomka for smooth functioning of society and main- taining social cohesiveness. The concept of sacred groves that revolves around the religious beliefs has brought some special significance in the life of Gonds and their associated tribal groups such as Mawasi in the study area. The customary rules established by these tribal groups, especially with respect to the sacred groves, have paved the way for conservation of biodiversity from the his- torical past. The established customary rules may vary from place to place and grove to grove but the goal is same, which follows the similar philosophy. These traditional rules often prohibit the felling of trees and the killing of ani- mals, except when trees are required for the construction and repair of religious buildings or in special cases do allow collection of firewood, fodder, and medicinal plants by local people [22,23]. As a result of these re- strictions, the biodiversity in such sacred groves are pre- served over many generations, and still exist today. The sacred groves are the last home of some endangered spe- cies, as observed in Kodagu district of southern Indian state of Karnataka [24], and also are known to represent the only exiting climax vegetation communities in northeastern India [23]. Numbers of studies have sup- ported the role of sacred grove in conservation of biodi- versity across the different parts of India including West Bengal [25], Northeast India [26] and Eastern Ghats [12]. In PBR, besides conservation of biodiversity, the role of sacred groves is also important as a life support sys- tem. The sacred groves help tribal communities by pro- viding edible fruits, leaves, fibers and medicinal plants. The people viewed that the required species if not found elsewhere around their village surroundings, there are high probability of occurrence of such species in the sa- cred grove sites by the grace of their local deity. At pre- sent, wh en in most p ar ts of th e wor ld th e fore st cov er an d the biodiversity are dwindling; these sacred groves are increasingly being recognized as the stronghold for pre- cious biological species. More than 130 major ethnic communities live in eastern Himalayan region of India and it was not uncommon in the past to locate here one sacred grove maintained by each village community [20]. The motive behind the foundation and evolution of such sacred groves may vary. However, it has been shat- tered in many parts of the world, especially in Europe, Central Asia and Middle East, where sacred groves have perished often without leaving a trace [6]. In contempo- rary period there is a great concern of the people as well as scientists working in the biodiversity conservation on the management of such sacred groves. In few places within India the sacred sites and sacred landscapes are also reported threatened by various external factors [1,2]. It has led to the declining of plant species and other ma- terials from the sites. It is perceived that the sacred groves are not only important for religious values, which contribute significantly in maintaining the village eco- system and surrounding biodiversity [7], but they are also culturally rich and living place of deities and spirits, which has larger significance. Given the importance of sacred groves in the conser- vation of biodiversity and ecosystem, there is a need to take care of such sites, and attempts should be made to maintain the sanctity o f these sacred groves. People must be made aware of such traditional conservation practices and they should bear its sanctity and values in mind while looking into commercial interests. It is importan t to develop management approaches in order to encourage the conservation of sacred groves. It is a need of hour to recognize the values of traditional institutions of sacred groves, the existing evidence for their effectiveness in biodiversity conservation and create space for such con- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Sacred Groves and Conservation of Biodiversity in the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve of India Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 973 cepts while framing local, regional and national conser- vation policies and planning. 5. Acknowledgements I thank the Director, Indian Institute of Forest Management, for providing logistic support. Bhubaneswar Saber is ac- knowledge d for help in g in coll ect io n o f fi eld d ata . T he project was funded under the grant IIFM/RP-Int./CPK/2009- 11/04. REFERENCES [1] P. S. Ramakrishnan, “What is Traditional Ecological Knowledge?” In: P. S. Ramakrishnan, R. K. Rai, R. P. S. Katwal and S. Mehndiratta, Eds., Traditional Ecological Knowledge for Managing the Biosphere Reserve in South and Central Asia, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2002, pp. 3-12. [2] C. P. Kala, “Ethnobotanical and Ecological Approaches for Conservation of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants,” Acta Horticulturae, Vol. 860, 2010, pp. 19-26. [3] B. S. Sajwan and C. P. Kala, “Conservation of Medicinal Plants: Conve ntional and Contempor ary Strategies, Regula- tions and Executions”, Indian Forester, Vol. 133, No. 4, 2007, pp. 484-495. [4] S. Tokarev, “History of Religion,” Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1989. [5] J. D. Hughes, “Pan’s Travel: Environmental Problems of the Ancient Greek and Romans,” Johns Hopkins Univer- sity Press, Baltimore, 1990. [6] B. Gowda, “Sacred Plants,” Kalpataru Research Academy, Bangalore, 2006. [7] M. Gadgil, F. Berkes and C. Folke, “Indigenous Knowl- edge for Biodiversity Conservation,” A Journal of the Human Environment, Vol. 22, 1993, pp. 151-156. [8] K. C. Malhotra, Y. Ghokhale, S. Chatterjee and S. Srivastava, “Cultural and Ecological Dimensions of Sa- cred Groves in India,” INSA, New Delhi, 2001. [9] B. Ramachandran, “Significance of Kavu—A Note on the Sacred Grove of Kerala in Eco-Cultural Context,” Jour- nal of Human Ecology, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1999, pp. 285-288. [10] P. Joshi and Y. Shrivastava, “Drops of Nature Conserva- tion—Sacred Grove,” Journal of Human Ecology, Vol. 11, No. 5, 2000, pp. 327-330. [11] V. Xaxa, “Oraons: Religion, Custom and Environment,” In: G. Sen, Ed., Indigenous Vision, Saga Publication, New Delhi, 1991, pp. 101-109. [12] M. Gadgil and V. D. Vartak, “Sacred Groves of Western Ghats in India,” Economic Botany, Vol. 30, 1976, pp. 152-160. doi:10.1007/BF02862961 [13] V. D. Vartak and M. Gadgil, “Studies on Sacred Groves along the Western Ghats from Maharashtra and Goa: Role of Beliefs and Folklores,” In: S. K. Jain, Ed., Glimpses of Indian Ethnobotany, Oxford University Press, Bombay, India, 1981, pp. 272-278. [14] M. Gadgil and F. Berkes, “Traditional Resource Man- agement Systems,” Resource Management and Optimiza- tion, Vol. 18, 1991, pp. 127-141. [15] V. Bhasin, “Religious and Cultural Perspective of a Sa- cred Site – Sitabari in Rajasthan,” Journal of Human Ecology, Vol. 10, 1999, pp. 329-340. [16] S. A. Bhagwat and C. Rutte, “Sacred Groves: Potential for Biodiversity Management,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, Vol. 4, No. 10, 2006, pp. 519-524. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2006)4[519:SGPFBM]2.0.CO;2 [17] EPCO, “Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve,” Environmental Planning and Co-ordination Organization, Bhopal, 2001. [18] E. A. Jayson, “An Ecological Survey at Satpura National Park, Pachmarhi and Bori Sanctuaries, Madhya Pradesh,” Indian Journal of Forestry, Vol. 13, No. 4, 1990, pp. 288-294. [19] C. P. Kala, “Home Gardens and Management of Key Spe- cies in the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve of India,” Journal of Biodiversity, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2010, pp. 111-117. [20] C. P. Kala, “Ethnomedicinal Botany of the Apatani in the Eastern Himalayan Region of India,” Journal of Ethnobi- ology and Ethnomedicine, Vol. 1, 2005, pp. 1-12. http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/pdf/1746-4269-1-11. pdf [21] P. C. Alexander, “Buddhism in Kerala,” Annamalai Uni- versity Historical Series, No. 8, Madras, 1949. [22] D. Brandis, “Indigenous Indian Forestry: Sacred Groves,” Oriental Institute, England, 1897. [23] P. S. Ramakrishnan, “Conserving the Sacred for Biodi- versity: The Conceptual Framework,” In: P. S. Rama- krishnan, K. G. Saxena and U. M. Chandrashekara, Eds, Conserving the Sacred for Biodiversity Management, Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., New Delhi, 1998, pp. 3-16. [24] S. A. Bhagwat, C. G. Kushalappa, P. H. Williams and N. D. Brown, “A Landscape Approach to Biodiversity Con- servation of Sacred Groves in the Western Ghats of In- dia,” Conservation Biology, Vol. 19, No. 6, 2005, pp. 1853-1862. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00248.x [25] P. K. Pandit and R. K. Bhakat, “Conserving of Biodiver- sity and Ethnic Culture through Sacred Groves in Mid- napore District, West Bengal, India,” Indian Forester, Vol. 133, No. 3, 2007, pp. 323-344. [26] A. D. Khumbongmayum, M. L. Khan and R. S. Tripathi, “Sacred Groves of Manipur—Ideal Centres of Biodiver- sity Conservation,” Current Science, Vol. 87, 2004, pp. 430-433.

|