Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 680-690 doi:10.4236/me.2011.24076 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME International Modularity and Offshoring in Spanish Industry* Sandra Valle, Lucía Avella, Francisco García Department of Business Administration, Universidad d e Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain E-mail: svalle@uniovi.es, lavella@uniovi.es, fgarciap@uniovi.es Received May 10, 201 1; revised July 2, 2011; accepted July 14, 2011 Abstract This paper aims to analyze participation by Spanish industrial firms in the marked process of international production modularity or fragmentation that is taking place on a global scale. It studies whether firms use offshoring (that is, transfer activities abroad), what type of activities are offshored, the type of offshoring used, the main target countries, the reasons for offshoring and the benefits it brings. Qualitative research into four Spanish business groups shows that they all use offshoring, mostly outsourcing manufacturing to inter- national suppliers. When choosing offshore location, these groups aim to achieve not only cost savings but also advantages from the agglomeration of the agents with which they need to interact, as well as access to new markets and relevant resources (infrastructure, auxiliary industry, production capacity, technology and know-how). Keywords: International Modularity, Offshoring, Captive Offshoring, Offshore Outsourcing 1. Introduction Globalization, coupled with the current dynamic nature of markets, fast technological change-especially in com- munications- and increasing co mpetition from new inter- national players—particularly emerging countries with lower income and wage levels, is placing firms under great pressure, leading them to adopt changes in the or- ganization and l ocati on o f thei r val ue chains. On the one hand, globalization provides firms with opportunities to target a larger number of markets and suppliers of raw materials and components [1]. On the other hand, constant technological change is breaking down the barriers associated with physical, geographic and/or cultural distance, and even with time differences [2]. As a result, businesses can adopt a modular approach, breaking up their value chains, specializing in their core activities and transferring the rest to foreign countries which now have more open markets in addition to unique resources and/or capabilities. In this way, firms are able to take up opportunities fo r cultural, administrative, geo- graphic and economic arbitrage, making the most of dif- ferences between countries and searching for economies through intern ational specialization [3]. The combination of modularity and offshoring, that is, of fragmentation and the use of resources outside the firm’s home country, is creating a worldwide panorama of value chains that are broken up into separate, specia- lized activities -innovation, component design, industrial design, logistics, manufacturing, sales and after-sales service, amongst others- which are carried out by differ- ent firms in different parts of the world, giving rise to international pr od uct i o n net works. The purpose of this research is to analyze whether Spanish industrial firms are participating in this process of international production fragmentation by modifying the organization and location of some of the activities in their value chains. More specifically, the aim of the study is to identify which activities are being outsourced to other firms in foreign countries and which ones are being carried out internally but relocated to different countries. The study also focuses on the reasons why such deci- sions are reached, the benefits sought and the risks taken. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes what is understood by offshoring. Section 3 describes the methodology used for the em- pirical research. This is based on case study and can therefore be categorized as qualitative. Section 4 presents the analysis of four large Spanish business groups and discusses the main findings. Finally, section 5 concludes. *The authors would like to thank Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tec- nología (MICINN-09-ECO2009-08485) for its financial support.  S. VALLE ET AL.681 2. International Modularity and Its Consequences: Offshoring The option of combining fragmentation (modularity) of the production system with economic internation a lization leads many firms to take key decisions on the organiza- tion and location of the activities in their value chain. With regard to organization, firms have to decide which activities will continue to be carried out internally within the firm and which to outsource to other independent national or international companies. And with regard to location, they have to decide whether those activities carried out internally are to be located in the firm’s home country or offshore. Offshoring includes both internation al outsourcing and offshore location choices. That is, offshoring is the trans- fer of activities to foreign countries, eith er to subsidiaries so that the firm gives up neither ownership nor control (offshore location or captive offshoring), or to indepen- dent firms (international outsourcing or offshore out- sourcing) (see Table 1). This definition of offshoring is in line with that used by authors such as [4] and [5]. The choice of offshore outsourcing or captive offshor- ing1 will depend on the relative advantages firms consi- der they will obtain from carrying out activities inter- nally rather than having them done by outside suppliers, as well as on the advantages of transferring them in both cases to a foreign country. In offshore outsourcing, firms acknowledge the advantages of outsourcing activities, that is, to focus on their core competencies and to resort to the greater capabilities of specialized suppliers. The resulting benefits of cost, quality and organizational learning make up for the transaction costs involved. How- ever, in captive o ffshoring, the advantages of outsourcing seem limited. When the transaction costs (mainly oppor- tunism), the possibility of losing management control and the risks associated with knowledge spillovers to- wards outside suppliers are too high, then firms choose to internalize activities while reaping the benefits ob- tained from the superior resources to be found abroad. In such cases, the advantages of setting up subsidiaries in foreign locations make up for the location-specific risk factors [2]. In addition, there may be other reasons why firms de- cide to transfer activities to o ther countries and outsource them to independent suppliers. These may be, among others, volatile demand, fierce competition from new global agents or institutional pressure and increasing costs. By outsourcing firms are able to: transfer the bur- den of capital investment and the risks of overproduction to third parties; save on labor costs by freeing themselves Table 1. Organization and location of activities in the value chain. Where the activity takes place Who carries out the activity Within the firm’s home country Abroad The firm In-house development Captive offshoring (Offshore location) An outside supplierDomestic outsourcing Offshore outsourcing (International outsourcing) OFFSHORING of labor-intensive processes; utilize crucial resources on key tasks; use the superior, specialized capabilities of other firms; increase their organizational learning by sharing information and resources with other firms; they can make up for shortfalls in in-house resources; access unique resources, gain flexibility an d improve production efficiency. When resources are neither limited nor diffi- cult to imitate and/or substitute, firms can achieve great advantages in cost, time and quality by obtaining them externally [7]. As stated above, the final decision on whether to out- source or not will depend on whether the advantages are greater than the costs and risks involved in having to establish transactions with other firms. It should be noted that, in many of the countries to which firms are out- sourcing their activities, legal systems are beginning to fall into line with western standards and provide a con- siderable degree of protection. This means that costs to ensure confidentiality are becoming comparable to those of industrialized countries. Therefore, the costs of infor- mation and coordination are decreasing [8], making such countries much more attractive. So the reduction in trans- action costs can be said to be facilitating trade across borders. On the other hand, there may be a number of reasons for deciding to transfer activities abroad but establishing owned units (captive offshoring). Many firms transfer their production to other countries because labor both technical and services is cheaper. Since labor costs often represent a large proportion of a firm’s operating costs, this can be a significant way of achieving cost savings. Other firms may need the sort of skilled professionals that are not available in their home countries2 [9]. Even though cost reduction is an important incentive, it is not the only reason for captive offshoring. Another reason to choose an offshore location may well be the need to sell in the country of destination, either because it is a new market in which customers can now afford to buy or be- 2Moreover, in these cases, the relative advantages of human capital stem not only from their cost or their greater skills, but also from time. Having personnel in different locations in different time zones allows a continuous workflow, which substantially increases total productivity and speeds work up [2]. 1Some authors, such as [6], consider an intermediate hybrid possibility: going abroad through a joint venture. However, this study focuses only on the extrem e o p t i o n s -captive offshoring or offshore outsourcing. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. VALLE ET AL. 682 cause a large number of potential customers will start to consume once jobs are available, providing them with regular wages and opportunities [10]. Therefore, poten- tial offshore locations should not be seen only as inter- esting sources of suppliers, but also as sources of future customers. If a privileged market position can be achieved, this may turn into a competitive advantage for the firm [6]. In addition, if the firm operates in the coun- try in which it hopes to sell its produ cts, proximity to the market will facilitate awareness of customers’ needs, tastes, preferences and local trends, so the firm will be able to keep ahead of the market. The type of product to be sold may also be a reason for captive offshoring [10]. Localizing production close to markets is especially relevant in the following cases: products that have to be manufactured complying with national specification s, products th at have to be tendered, perishable or fragile products that might be damaged during transport to their final destination or market, and heavy or bulky products. Following market tren ds and imitating o thers may also be a reason for captive offshoring. A firm may decide to invest abroad because it has seen other firms do so [11]. But the usual reason is to gain access to resources that are not available in the firm’s home country. In fact, some studies have shown that internationalization may be based on the search for new assets (asset-seeking in- ternationalization) [12-14]. A shortage of land, capital, labor, capabilities, know-how or any other resource may make a transfer to another country inevitable. Captive offshoring may allow firms to enter countries by directly acquiring unique emerging resources, then retaining di- rect control over them. First-movers can develop this potential and may end up gaining a competitive advan- tage. 3. Research Methodology As stated above, the main purpose of this research is to analyze and draw some relevant conclusions on partici- pation by Spanish industrial firms in international pro- duction modularity or fragmentation through offshoring. The analysis focuses on the following questions: Of all the activities involved in the firm’s value chain, which ones have been outsourced to foreign suppliers and which ones have been transferred to subsidiaries abroad? What are the main reasons why firms make these decisions? What benefits has the firm achieved by transferring activities abroad? What risks have been taken? Given these objectives, case study was adopted as the research methodology as this allows a phenomenon to be studied within its context, using multiple sources of in- formation a nd analyzing a large number of vari abl e s 3. The research covered four Spanish business groups that are active internationally and are known to have transferred some of their activities to foreign countries. Field work was carried out between March and July 2009. Semi-structured interviews were held with owners, managers and employees at the facilities which each group has in its respective region of origin (two in Span- ish region A and two in Spanish region B), requesting information on the whole group. Since the use of a re- search protocol helps increase bo th the reliability and the validity of the data obtained from the study [17], a semi- structured questionnaire was drawn up as a guide, though the interviews were always open. The multiple-respon- dent formula was also adopted because in most cases a single person does not have all the knowledge necessary on the subject under study and cannot provide all the data required for the research. Moreover, this eliminates the potential problem that answers from a single respon- dent may be subjective or subject to personal biases. All the researchers participated in each of the interviews. When compiling data for a case study, triangu lation is important, that is, the use and combination of different sources of information to study a single phenomenon. Such sources may include interviews, questionnaires, di- rect observation, analysis of documents or research into archives. The use of many sources of data helps increase the reliability of results, because it allows the researcher to carry out more thorough analyses, covering a broader range of factors [16], and basing conclusions on many sources of evidence [18]. In this study, triangulation has been achieved by complementing the information ob- tained in interviews with information obtained from the press and from the corporate websites. Additionally, once the report about the experience of each firm had been written (with the participation of all the researchers), the document was sent to the interviewees so that they could evaluate to what extent it was accurate and tallied with the conversations held during visits and, where ap- propriate, make corrections. The final information ob- tained is presented below. 4. Results and Discussion This section presents the main results of the empirical research. Firstly, the four cases under analysis are showed. Thus, the organization of each firm’s value chain is described, stressing the activities transferred abroad -both by outsourcing to third parties or by setting 3This methodology is appropriate in the early stages of research [15], when the aim is to study unusual phenomena for which there is no consolidated theoretical basis or when causal explanations are sough [16]. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. VALLE ET AL.683 up a subsidiary- and the reasons, benefits and risks in- volved. Secondly, a comparative analysis of the four cases studied is presented. 4.1. Main Results of the Case Study 4.1.1. Alf a 4 Alfa is a family-run group that competes mainly in three sectors: open-air toys, sports products and food products. Alfa exports its products to more than 70 countries. The activities involved in the group’s value chain are: R&D + i/design, logistics (purch asing, tran sportatio n and stocks management), manufacturing, quality control, administrative processes (administration, HR, cash…), marketing and after-sales services. Many of these activities are carried out in-house, some in Alfa’s home region (region A) and some others in Hong Kong. More specifically, the purchasing of materi- als and coordination of some of its sales and transport logistics have been transferred to Hong Kong. For this purpose, Alfa has set up a commercial subsidiary from which it can sell its products in markets in Asia, America and Europe. In addition to these in-house activities, Alfa also out- sources some activities to independen t suppliers, namely, HR administration and most of its manufacturing. HR management and administration is outsourced to an in- dependent firm in region A (domestic outsourcing). Pro- duction, except for 16% carried out in-house, is out- sourced to a Taiwanese and several Chinese manufactur- ers (internatio na l outs o urci n g). Of all the outsourced production, 65% comes from a Chinese manufacturer which, though not owned by Alfa, was set up to operate in the same way as Alfa and to supply it exclusively. For the rest of the outsourced pro- duction, Alfa has a portfolio of about 30 suppliers that were selected because they had the equipment, know- how and other resources that the exclusive supplier or other potential suppliers did not have. For example, it works with a firm in Shanghai w hich is one of the world best suppliers of high technology in traction. All the suppliers, which have to comply with a strict protocol drawn up by Alfa, carry out only the physical manufacturing, because all design and development (R&D + i) is still carried ou t in-hou se by Alfa in i ts ho me region. In fact, this function is so important that it has recently become an independent firm within the group. In spite of this high level of outsourcing, Alfa still car- ries out approximately 16% of its production within its plant in region A. This is due to the fact that Alfa con- siders there are certain high-technology products that cannot be outsourced to other firms, either because such firms do not have the necessary capability to manufac- ture them or because of the high risk of dissipation and loss of know-how. So, essentially, Alfa takes labor to China but has left the firm’s “brain” (what really adds value to its products) in its home facilities. Alfa had various reasons for choosing China as its offshore dest i n a t i on : The country was not unknown to the firm, as its chairman had had contacts in China since 1985. China has the required skilled labor that, in addition, is productive and cheaper. China has the necessary infrastructure. The Chinese government guarantees protection for foreign investments. Many of the firm’s competitors were already in Chin a before Alfa established there5. Hong Kong is the business hub in the toy sector, and many of Alfa’s most important customers are there. Alfa considers that it made the right decision in choosing China6. In spite of the cultural differences and the difficulties they entail, Alfa has a close relationship with all its Chinese suppliers, and shares information, resources and values with them. In addition to the man- agement team and the Office Manager in Hong Kong, Alfa has four people acting as links with all suppliers. They all speak Chinese and have received specific train- ing for this jo b . The main advantages for Alfa of outsourcing product manufacturing to China are: a) cost savings, b) organiza- tional learning, c) larger sales volume and market share, and d) improved profitab ility. Alfa considers that the main risks of offshore out- sourcing to China are: lower quality, longer lead times, loss of intellectual property, lack of sk ills in maintaining good relations with suppliers, and the potential for sup- pliers to turn into future competitors. Alfa has been able to prevent such risks from turning into real problems, mainly because of its careful selec- tion of suppliers, which have to follow the Alfa philoso- phy, and also because of its strategy of patenting all its innovations. Perhaps the only real risk is that of longer lead times, but this is offset by all the other advantages. Alfa plans to continue offshoring activities in China. 5Today, most of these competitors are considering relocating their ac- tivities once again. The new destinations would be Vietnam and Africa, mainly because prod uction is now cheaper there than in China. But Alfa is not planning to relocate. It knows that China will not be feasible in the future but, meanwhile, it prefers to achieve cost savings through automation. 6When Alfa decided to outsource production to China, it also consid- ered the possibility of outsourcing to a Polish supplier. But the latter’s rices, because of labor costs, were very similar to those in Spain, so i would not have been profitable. There were also problems with raw materials, because in Poland the tariff regime would have complicated customs formalities. Portugal was also considered but it was neither rofitable nor did it h a ve su i ta bl e i n frastructure. 4For reasons of confidentiality and at the request of the firms studied, fictitious names are used. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. VALLE ET AL. 684 In fact, it is considering creating a buffer warehouse in Hong Kong, similar to the one it has in region A. The aim is to have two strategically-located buffer ware- houses in the world one for medium and large customers buying from Europe, America, the Middle East and Af- rica, and another for mediu m and large customers bu ying for the whole world but from Hong Kong. This new pro- ject will allow the firm to offer a good service to its cus- tomers, while improving the positioning of its products internationally. Moreover, with this investment, Alfa will be setting up a new logistics management business for all the firms that do not have the resources, capability or know-how to manage their own logistics. The firm is also considering the possibility of entering Africa by setting up a facility in Tunisia. The Alfa group is, therefore, a neat example of a firm that has resorted to offshoring, specifically in China. It uses the two types of transfer modes being analyzed, both offshore outsourcing (mainly manufacturing) and captive offshoring (the purchase of materials and coor- dination of some sales and transport logistics). 4.1.2. Beta The Beta group is a business holding that manufactures, provides advisory services and distributes products and services in the electricity and electronics sectors and controls industrial and domestic facilities. All the administrative processes required in its value chain tax management, accounting, HR, etc. are carried out in-house but in a decentralized fashion, that is, in each of the group’s facilities. The same happens for dis- tribution and sales, carried out internally at each of Beta’s distribution centers located in Spain, Portugal, Poland, Mexico and China. R&D + i is also carried out in-house, thou gh it is cen- tralized for the whole group. The firm has its own tech- nology center located in its home region (region A), which carries out basic research, industrial research and experimental and industrial development. Beta has main- tained this activity in its home region because it runs smoothly as a result of cooperation with the university, with various technology centers and with the local gov- ernment. Manufacturing is partly carried out by Beta in-house, in its Spanish and its Chinese plants, and partly out- sourced to manufacturers in China. More specifically, in Spain it produces the mechanical parts of the electrical equipment because in Spain it has the necessary know- how and technological and intellectual capital, so there would be no point in transferring it elsewhere. Beta ma- nufactures all the electronics components in China. This type of production was previously entirely outsourced to third parties, but it is now done in-house. For this pur- pose, Beta has a plant in Haian (Jiangsu) and another in Zhen-Zhen. The Haian plant carries out production em- ploying local labor. The Zhen-Zhen plant carries out the final technological development of products, prior to production and based on prototypes sent from Spain, taking into account the need to adapt these products to the conditions in the countries in which they are to be sold. This plant also carries out quality control on all products manufactured in China. Initially, Beta mainly outsourced because electronics manufacturing know-how was mostly in the hands of Chinese manufacturers but, over the years, the firm has gained greater know-how and experience and now con- siders that, by maintaining tighter control over costs, labor and overheads, it can be more competitive by ma- nufacturing its products itself rather than by outsourcing. In fact, the only production that Beta currently out- sources is the manufacture of highly innovative end pro- ducts. When Beta detects products with potential, for which it does not yet have the necessary know-how or technological resources, it starts out by outsourcing pro- duction to Chinese manufacturers in order to benefit from their higher capability and, meanwhile, learns with the aim of manufacturing the products itself. Beta chose China for the following reasons: Access to the electronics manufacturing know-how that is available in China, the location of the world’s best centers for this type of technology. The wish to sell in China, which is not only the world’s largest market but it also has very well-deve- loped infrastructure, facilitating distribution. The group considers that, in order to have a trade presence in China, it is necessary to manufactu re there. Cost saving. Production costs in China are much lower than in Spain. In electronics components, labor represents a very large proportion of the final cost (these are very labor-intensive processes) and labor is cheaper in China. But, in the case of Beta, it should be stressed that this was not the main reason because, as stated above, the firm has established in China to sell there, not to bring cheaper products to Spain. Beta sees China as a land of opportunity, not only for technology and industry, but also for sales. By transfer- ring activities to China, the firm can obtain the following benefits: access to new markets, greater knowledge of local customers, cost savings, and enhanced learning possibilities. For the future, the Beta group is also considering set- ting up activities in Mexico. The firm believes that this country would be optimal for replicating their Chinese business model, given that operations and costs would be similar. Mexico would also be a good platform for en- tering other markets. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. VALLE ET AL.685 The Beta group, therefore, is another example of a firm that offshores some of its value chain activities. The chosen destination country is China, and Beta uses the two types of transfer modes analyzed. On the one hand, Beta started out in China with its own subsidiaries and, on the other hand, the group outsources activities to a notable number of local suppliers there. 4.1.3. Gamma Gamma is a footwear and accessories firm in Spanish region B. In its facilities in Spain, it carries out all R&D, engineering and design, the production of prototypes (the first shoe), 10% of final manufacturing7, most of its lo- gistics, administrative processes and sales, and after- sales services. However, some of Gamma’s activities are not carried out in-house, namely those relating to manufacturing, which is almost totally outsourced (90%). Currently Gamma outsources the production of shoes to independ- ent firms in Spain, China and India. The firm is also car- rying out tests in Bangladesh and Morocco8. Offshore outsourcing originally was a strategy for the firm, but has now become a necessity. For reasons of cost, it would no longer be feasible to carry out all manufacturing in Spain but, though production cost is one of the basic reasons why the firm uses foreign sup- pliers, it is not the only one. Gamma now also interna- tionally outsources an increasing proportion of its pro- duction for reasons of production capacity which, in China for example, is enormous. In fact, shoe production can only be outsourced to China when it involves a huge sales volume, that is, large-scale production. If not, Chi- nese manufacturers are not interested. India is different, however, and there it is possible to achieve very good prices even for small batches. Auxiliary firms are extremely important in the foot- wear industry. In Spain, they have gradually disappeared as the industry has developed. Gamma has therefore sought countries where this necessary auxiliary industry is still available. The firm has also sought out technical capability of the sort that can meet Gamma’s quality and service requirements. Even though production is out- sourced, quality is strictly contro lled by Gamma in order to guarantee product uniformity. This control is carried out by the firm’s own specialists who check that suppli- ers meet the firm’s stipulations regarding materials, processes, etc. Other important consider ations in offshore outsourcing are transport costs and times, as well as production times. Seasonal products (those for which orders are placed months in advance) can be outsourced in distant coun- tries. However, fashion or “replacement” products (which need to be available in just a few days) require prox- imity. In all cases, Gamma’s relations with its suppliers are based on long-term collaboration agreements and on a protocol for action which has resulted from the firm’s learning process over the years. Communication is car- ried out by an international quality manager who deals with all foreign relations and acts as mediator. If prob- lems arise with a supplier, the firm can resort to a group of alternative suppliers that it has in each country. The main benefits obtained by Gamma from offshore outsourcing its manufacturing are: cost reduction, less capital investment, greater flexibility in line with fluctu- ating demand and organizational learning relating to management of the whole chain of suppliers. Offshore outsourcing has also led to increased profitability and productivity. However, the group does not obtain advan- tages in quality (it is the same to outsource internation- ally as to produce in-house in Spain), or in time (lead times are maintained if outsourcing is in Spain, but in- crease in offshore production). Nor does the firm achieve greater innovation or faster development. The risks per- ceived by Gamma from offshore outsourcing are basi- cally increased lead times and the loss of intellectual property. Gamma is, therefore, another example of a firm that resorts to offshoring though, in this case, only to offshore outsourcing, not captive offshoring. As stated above, it outsources internationally those activities in which eco- nomies of scale are possible and which are labor-inten- sive, such as manufacturing, but it has not transferred any plants from Spain to another country. The firm could afford to do so but obtains greater benefits from out- sourcing. 4.1.4. Del t a Delta is a toy manufacturer from the same region as Gamma. It has several product lines but two main ones- one for baby entertainment, safety and hygiene (highly- innovative electronics produ cts), and the other for educa- tion (toys and teaching materials). Delta carries out the following activities in its value chain in-house most of its design, purchasing, quality 7For this purpose, it has its own plant in Spain which does not make a rofit but nor does it incur losses. It is being retained because of the firm’s social commitment (to preserve jobs) and in order to preserve the firm’s history. This plant is used to do production tests, to produce very small batches or t o check design feasibility. 8Originally, everything was outsourced within Spain. Afterwards, out- sourcing to Portugal began, given that Portugal has a longstanding tradition in footwear production, it has auxiliary industry and its trans- ort and production costs are low. Su sequently, the firm also started outsourcing to Romania, where costs were also reasonable. But, in spite of cheap prices, Romania is not a great footwear producer and has no auxiliary industry, so materials had to be sent from Spain, which was not sustainable for large-scale production. Eventually, the firm decided to look for manufacturers in China. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. VALLE ET AL. 686 control, logistics, administrative tasks and part of its sales. Other activities such as marketing, assembly and manufacturing are ou tsourc ed marketin g an d assembly to local firms, and manufacturing to both Spanish and for- eign firms. Nevertheless, product line determines the choice of in-house d evelopment, national or internation al outsourcing. On the one hand, for the educational product line, 100% of engineering and design is carried out in-house, these being the firm’s core competencies. Manufacturing is almost completely outsourced (approximately 50% in Spain and 50% abroad), and only a very small proportion is carried out in-house, that involving a special, un- breakable material designed by Delta which they wish to prevent from being copied. 70% of the firm’s interna- tional outso urcing goes to China, 20% to Taiwan and the remaining 10% to Korea, Thailand and Malaysia. De- pending on each specific article, either full product manufacturing is outsourced, or just the manufacturing of some components, with assembly taking place in-house in Spain. On the other hand, for the electronics product line, th e physical design is also carried out in-house but the tech- nological design and engineering are fully outsourced. Many of Delta’s technological products have been de- veloped by other firms. Delta’s involvement in product design is then limited to product customization, adapta- tion to the firm’s product collection and affixation of its own brand. The firm usually looks for fairly exclusive products but, if it cannot find them, it also produces its own designs. In this case, it only carries out the external design, and has the technological development carried out by experts, mostly by firms in Hong Kong and Tai- wan. Delta contacts the engineering teams in these firms and explains the specific characteristics it wants the product to have. This method seems reasonable because Delta is not a technology firm, so this activity is not among its strengths. The firm does not have the neces- sary resources or capabilities to be able to develop this type of product internally. Moreover, considering the speed of technological change, in order to avoid reaching the market with obsolete technology, it is important to resort to manufacturers having the necessary experience and know-how. Rather than producing in-house, it is much faster and more efficient for Delta to outsource the technological development and use the global network of specialists. In general, this firm considers that one of the main advantages of outsourcing is that they can produce when necessary and determine costs ex-ante (in-house manu- facturing is more risky as costs only become clear ex-post). However, in addition to cost, there are many other re asons wh y off shore ou tsour cing may be p referr ed. Delta also takes into account where global manufacturers are located and where it can find the know-how needed for its products. Ch ina is a strong player in toy manufac- turing and has extensive know-how in technological production, so offshoring there is a guarantee. In other words, the reasons why Delta decided to out- source internationally are: to reduce costs, to focus only on the firm’s core competencies (that is, channel and product specialization) and to better meet its product requirements. In the case of technological products, by outsourcing to foreign firms Delta aims to shorten lead times and to use the higher capabilities of other firms. Delta’s relations with all its Chinese and Taiwanese suppliers are always based on long-term agreements, aiming to achieve continuity and trust and, essentially, looking for b usiness allies. Supplier selection criteria are price, supplier’s characteristics and trust. These firms should be experts and enjoy a degree of prestige which should stem not only from their low costs. It is, however, the manufacturer that has to guarantee quality. The greatest risk perceived by this firm in interna- tional outsourcing is loss of control over the product, which is inevitable. However, Delta is not afraid of los- ing data or know-how because it has observed that Asian suppliers tend to respect their customers. Delta can therefore be considered another example of a firm that uses offshoring but only offshore ou tsourcing . It has not relocated any of its production facilities. 4.2. Comparative Analysis of the Cases Studied Table 2 compares the situation of the firms studied with regard to: 1) the activities in the value chain that are off- shored internationally, 2) th ose that are carried out inter- nally but in a different country, 3) the destination coun- tries, and 4) the reasons for choosing them. The activities transferred abroad by the four groups analyzed are basically the same -primarily manufacturing, although the transfer mode differs. Alfa and Beta not only outsource production to foreign suppliers but have also set up their own facilities abroad. Gamma and Delta only use offshore outsourcing without relocating. None of the four groups studied have transferred their research and design abroad because of the strategic im- portance of this activity for all of th em. In Alfa and Beta, research and development and, above all, innovation, are a strategic priority and one of the main drivers of their success. For Delta, the educational nature of its toys makes design a priority, the main aim being to guarantee quality and the educational content. And for Gamma, design is one of its core competencies. As a result, none of these business groups seems prep ared to accep t either Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. VALLE ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 687 Table 2. Comparative analysis of offshoring decisions in the groups studied. Activities involved in the value chain Activities offshored (partially or fully) Method of transfer (outsourcing/subsidiary) Country chosen Reasons R&D + i/Design Purchasing Logistics Transport (partially) Owned facilities China Manufacturing Manufacturing (84%) Outsourcing China and Taiwan Quality control Administrative processes ALFA Sales and after-sales services Sales (partially) Owned facilities China It is not an unknown country. Has the necessary infrastructure. Possesses qualified, productive, cheap labor. Guarantees protection of fore i gn investments. Competitors and customers are in this country. R&D + i Electronics products : latest technology, manufacturing and quality control Owned facilities China Manufacturing Very new products Outsourcing China Administrative processes BETA Distribution and sales Possession of know-how on elec- tronics. Desire to sell in China. Lower manufacturing costs because of cheaper labor R&D Engineering Design Manufacturing Manufacturing (90%) Outsourcing China and India Logistics Logistics (partially) Outsourcing China Administrative processes GAMMA Sales and after-sales services Production cost Production capacity: -Existence of auxiliary firms -Technical capacity -Transport cost -Timing (production and transport) Design Electronic Outsourcing China Sourcing Engineering Electronic Outsourcing China Manufacturing Manufacturing (50%) Outsourcing China, Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia Quality control Logistics Administrative tasks Marketing DELTA Sales and after-sales services Production cost Concentration of worldwide production. Location of know-how and expert ise Source: Drawn up by the authors. the high risks involved in outsourcing R&D (potential undesired dissemination of knowledge amongst other firms and/or loss of control of such activities) nor the operating difficulties involved in locating R&D in other countries (managing the flow of information and coordi- nating with other related activities in the value chain). In respect to location, the four groups’ have out- sourced/relocated activities primarily to China, although some activities have also been outsou rced to other South- East Asian countries and to India. In China, costs, and especially labor costs, are low. For both Alfa and Gamma, China was the inevitable choice because the costs they  S. VALLE ET AL. 688 faced in Spain did not allow them to produce competi- tively. Offshoring has allowed them to survive. Beta and Delta also enjoy lower production costs in China, but for them this was not the main reason for their choice. So, in addition to cost, there have been other reasons driving location choice market size, industry trends, the existence of a powerful auxiliary industry, production capacity and the possibility of accessing better technolo- gies and/or products. For example, for Beta, in addition to collaborating with Chinese firms in technology deve- lopment, gaining know-how and more advanced tech- nologies had priority. For Alfa, both its main competitors and main customers are present in China so it was prac- tically inevitable for the firm to enter China in order to compete. Similarly, the suppliers of electronics technol- ogy for one of Delta’s product lines are concentrated in China, so the firm necessarily has to purchase goods there. And for Gamma, what was particularly relevant about the Chinese market was the concentration of aux- iliary firms which are essential for footwear production. 5. Conclusions Based on case study methodology, this paper analyzes whether and how Spanish industrial firms are interna- tionally reorganizing and relocating at least part of their value chains and, thus, are taking part in the current world scale process of international production disinte- gration. The study analyzes offshoring decisions (both offshore outsourcing and captive offshoring) by four Spanish groups. More specifically, it is focused on the type of activities transferred abroad, the transfer mode, the choice of destination countries, the reasons driving offshoring decisions, the advantages obtained and the risks faced in the process. The following conclusions may be drawn from the study. Firstly, of all the activities in the value chain of the Spanish firms analyzed, the ones that tend to be trans- ferred abroad are those relating to product manufacture (and to a lesser extent logistics and sales). Firms tend to leave their R&D + i activities in their country of origin. Most of the activities transferred are routine, standard- ized, labor-intensive activities, in which a high volume of production can be reached, with a limited technologi- cal component and not based on secret information (Figure 1). Secondly, although the business groups analyzed transfer activities to other countries either by outsourcing them to local, independent firms offshore outsourcing or by setting up subsidiaries captive offshoring, the former prevails over the latter (Figure 2). Thirdly, activities are primarily offshored to Asian countries, and particularly to China (Figure 3). A lthough Figure 1. Type of offshored activities. Figure 2. Transfer mode used. Figure 3. Chosen offshore location. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. VALLE ET AL.689 low costs especially labor costs is one powerful reason why the four analyzed firms chose China over other po- tential locations, it must be noted that this was not the only, nor the most important motive in this respect. Firms also emphasized the attractiveness of the Chinese market in terms of its large size, its infrastructure en- dowment, the existence of an important auxiliary indu- stry, its high production and technical capability, the positive attitude of its government towards foreign in- vestment and its better technologies and more advanced know-how in some industries. Also important for choos- ing China is the existence of other agen ts with which the firms studied need to interact (competitors, customers, suppliers and aux iliary firms). Thus, the concentration of the relevant agents in a single location is an important reason for select i ng a n offshorin g d est i nat ion. Fourthly, the list of advantages derived from the inter- national disintegration of the firms’ value chains is rela- tively long. Among these the analyzed firms mentioned large cost savings, the possibility of focusing on core competencies, taking advantage of favorable conditions offered by foreign locations or access to new markets. However, improved organizational learning is the most important benefit firms may reap from offshoring. By transferring part of their activities abroad, firms may gain access to greater technological and market knowledge, may improve awareness of state-of-the-art, more effi- cient processes and may acquire new or improve their existing skills, experience and know-how. Taken to- gether, these will lead to innova tive, fast, specialized and integrated operations. As a consequence, firm sales volume, market share, profitability and productivity may improve. Finally, although the firms studied perceived several potential risks of offshoring (reduced product quality, loss of incentives for R&D + i, increased lead times, loss of intellectual property, the loss of control or suppliers potentially turning in to future competitors), non e of these have turned into real problems for any of the firms ana- lyzed. Or if they have, the benefits achieved in the proc- ess of international disintegration have offset the prob- lems encountered. Although inferences from this stud y are limited by the small number of cases analyzed, it can be concluded that Spanish firms are involved in the process of international fragmentation that is taking place on a global scale. Off- shoring allows these firms to reap the benefits of specia- lization and to take advantage of specific locations worldwide. As a consequence, Spanish firms are im- proving their competitiveness and, above all, their sur- vival chances. Finally, it should be noted that th is qualitative study is only the starting-point for a more extensive future re- search line. Based on the general conclusions from this first study, the authors have the intention to develop and propose specific hypotheses to be tested in a broader sample of Spanish firms. The authors are particularly interested in analyzing to what extent offshoring is lead- ing firms to enter international networks. 6. References [1] Z. Fernández, “Desintegración e Integración Interna- cional de la Cadena de Valor,” Información Comercial Española ICE, No. 838, September-October 2007, pp. 147-156. [2] B. L. Kedia and D. Mukherjee, “Understanding Offshor- ing: A Research Framework Based on Disintegration, Location and Externalization Advantages,” Journal of World Business, Vol. 44, No. 3, 2008, pp. 250-261. doi:org/10.1016/j.jwb.2008.08.005 [3] P. Ghemawat, “Redefiniendo la Globalización la Import- ancia de las Diferencias en un Mundo Globalizado,” Deusto, Barcelona, 2008. [4] G. Grossman and E. Rossi-Hansberg, “The rise of off- shoring: It’s not wine for cloth anymore. In Federal Re- serve Bank of Kansas City, ” The New Economic Geog- raphy: Effects and Policy Implications, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August, 2426, 2006. [5] J. A. Alonso, “Fragmentación Productiva, Multilocali- zación y Proceso de Internacionalización de la Empresa,” Información Comercial Española ICE, No. 838, Septem- ber-October 2007, pp. 23-39. [6] C. Jahns, E. Hartmann and L. Bals, “Offshoring Dimen- sions and Diffusion of a New Business Concept,” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, No. 12, 2006, pp. 218-231. [7] W. Lankford and F. Parsa, “Outsourcing: A Primer,” Management Decision, No. 37, 1999, pp. 310-316. [8] M. Robinson and R. Kalakota, “Offshore Outsourcing- Business Models,” ROI and Best Practices, Mivar, 2004. [9] A. Y. Lewin, S. Massini and C. Peeters, “Why Are Com- panies Offshoring Innovation? The Emerging Global Race for Talent,” Journal of International Business Stud- ies, Vol. 40, No. 6, 2009, pp. 901-925. doi:org/10.1057/jibs.2008.92 [10] S. Berger, “Desde las Trincheras Cómo se Enfrentan Empresas de Todo el Mundo a las Fronteras de la Economía Global,” Empresa Activa, Barcelona, 2006. [11] W. J. Henisz and A. Delios, “Uncertainty, Imitation and Plant Location: Japanese Multinational Corporations 1990-1996,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Press Alpharetta, Vol. 46, 2001, pp. 443-475. doi:org/10.2307/3094871 [12] B. Kogut and S. J. Chan, “Technological Capabilities and Japanese Foreign Direct Investment in the United States,” Review of Economics and Statistics, No. 73, 1991, pp. 401-413. [13] W. Shan, and J. Song, “Foreign Direct Investment and the Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. VALLE ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 690 Sourcing of Technological Advantage: Evidence from the Biotechnology Industry,” Journal of International Busi- ness Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1997, pp. 267- 284. doi:org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490101 [14] T. Wesson, “A Model of Asset-Seeking Foreing Direct Investment Driven by Demand Conditions,” Revue Ca- nadienne des Sciences de l´Asministration, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1999, pp. 1-10. [15] K. M. Eisenhardt, “Building Theories from Case Study Research,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, No. 4, 1989, pp. 532-550. [16] R. K. Yin, “Case Study Research: Design and Methods,” Sage, London, 1989 . [17] C. Voss, N. Tsikriktsis and M. Frohlich, “Case Research in Operations Management,” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2002, pp. 195-219. doi:org/10.1108/01443570210414329 [18] S. K. Chetty, “The Case Study Method for Research in Small and Medium Sized Firms,” International Small Business Journal, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1996, pp. 73-85. doi:org/10.1177/0266242696151005

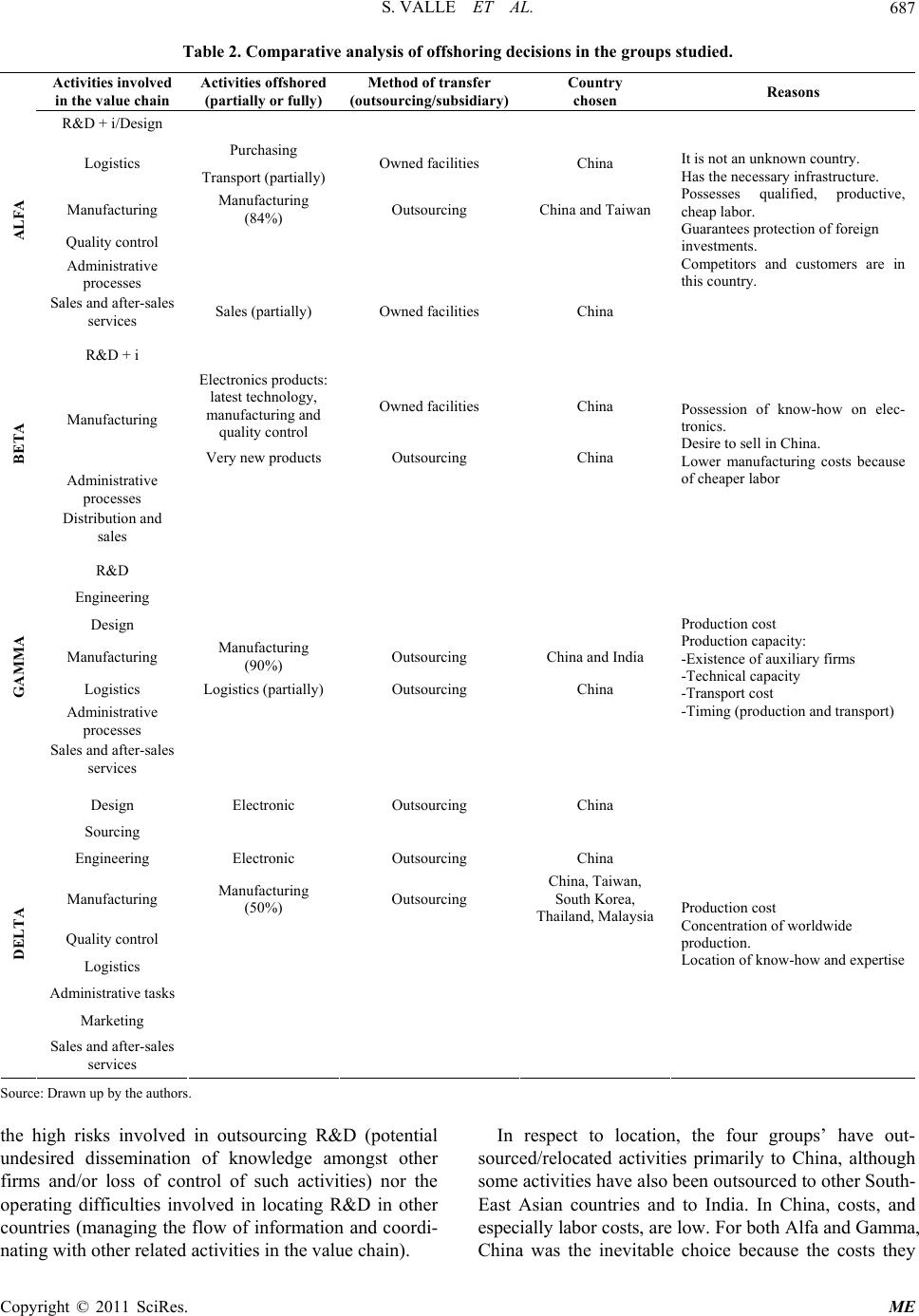

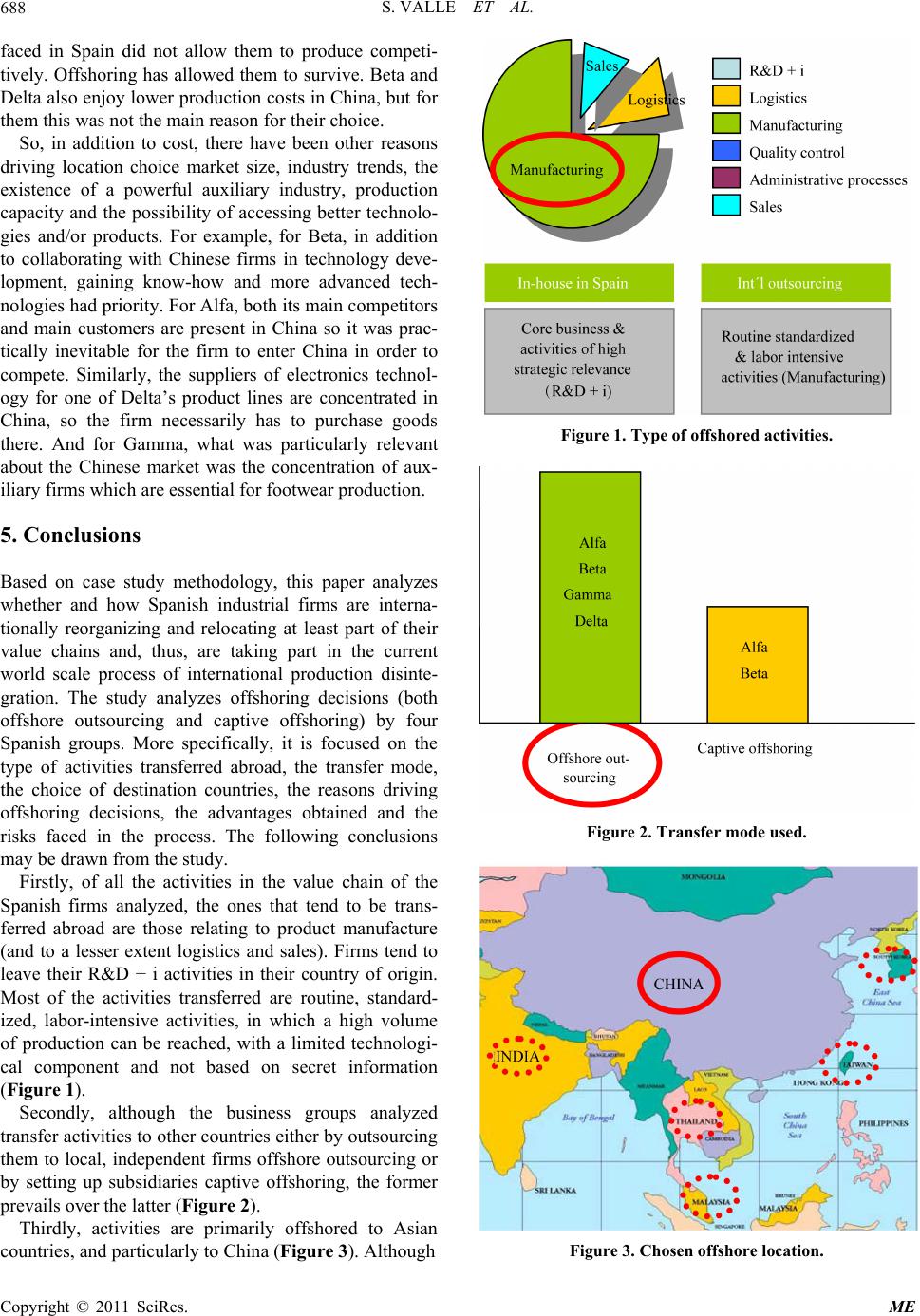

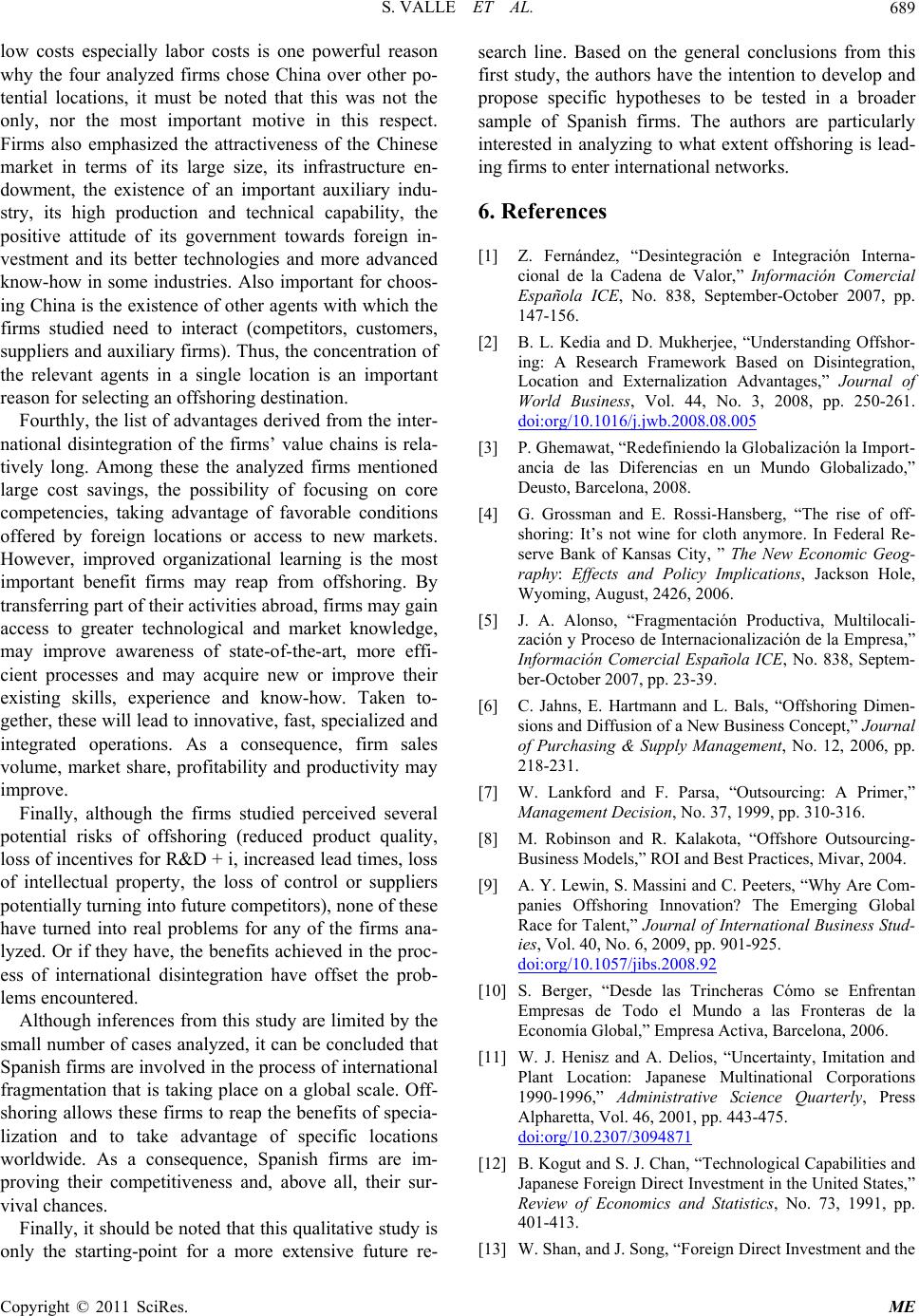

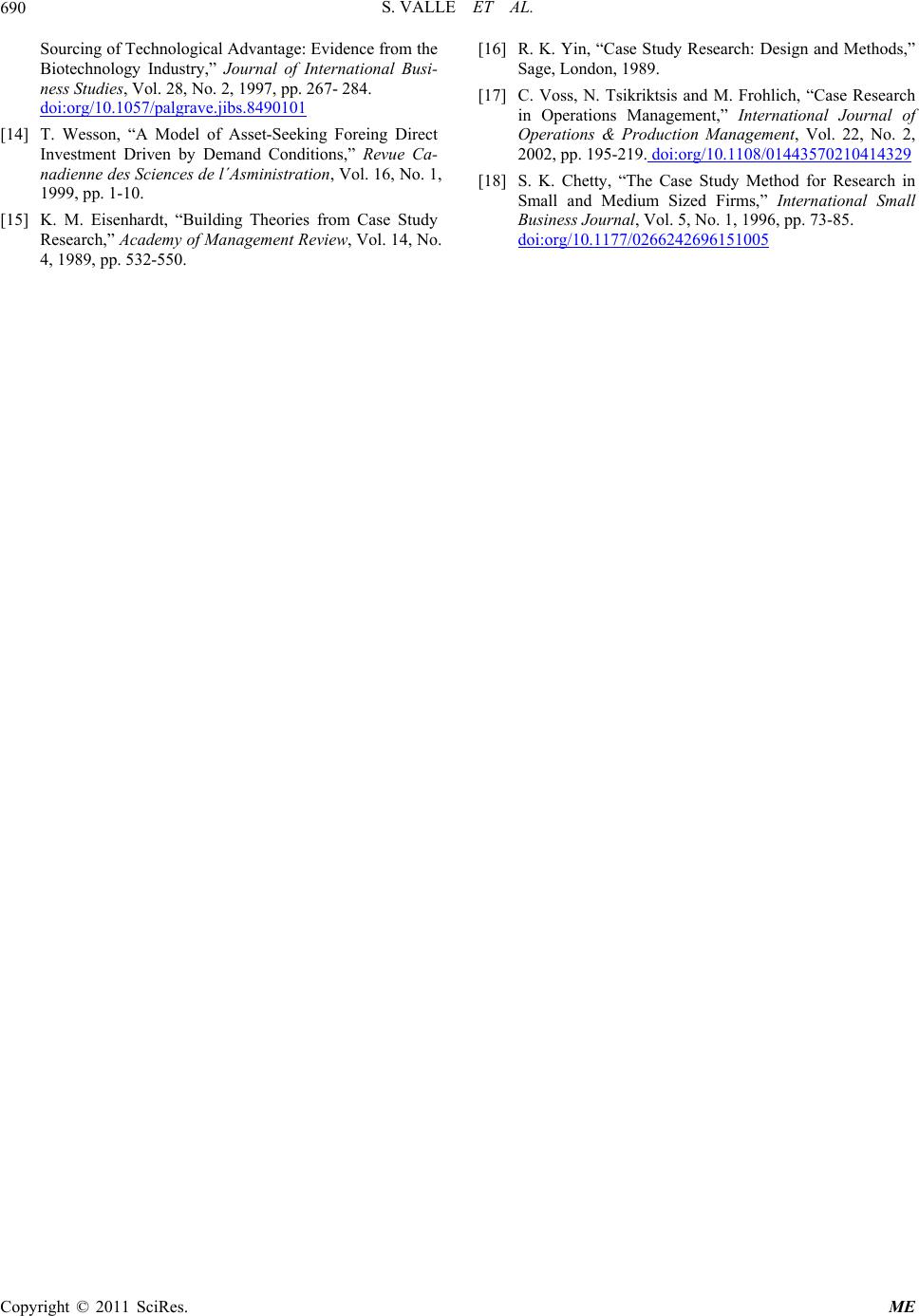

|