Surgical Science

Vol.3 No.11(2012), Article ID:24610,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ss.2012.311107

Doppler-Guided Transanal Haemorrhoidal Dearterialisation Is a Safe and Effective Daycase Procedure for All Grades of Symptomatic Haemorrhoids

1Cambridge Colorectal Unit and Department of Anaesthesia, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK 2Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK

Email: justin.davies@addenbrookes.nhs.uk

Received August 7, 2012, revised September 8, 2012; accepted September 17, 2012

Keywords: Transanal; Haemorrhoidal; Dearterialisation; Doppler; Guided; Haemorrhoid

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Doppler-guided transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation (THD), with the addition of rectal mucopexy, has been gaining popularity as a minimally invasive haemorrhoidal treatment. The aim of this study was to assess the outcomes of THD in patients with symptomatic haemorrhoids. Methods: All consecutive patients undergoing THD by a single surgeon over a 2 year period from 1st January 2010 were included. Results: THD was performed on 58 consecutive patients, with 46 (79.3%) having had previous haemorrhoidal treatment(s). Haemorrhoid grades were: 1 (n = 6); 2 (n = 12); 3 (n = 32); 4 (n = 8). The median number of THD ligations was 7 (range 4 to 9) and rectal mucopexies 3 (range 1 to 3). All procedures (100%) were carried out as daycase, with 1 readmission within 30 days (anal fissure). No patients required return to theatre. After median follow-up of 10.5 weeks (range 1 to 48 weeks, 2 lost to follow-up), 53 (91%) patients reported symptomatic resolution or significant improvement. Two (3.4%) patients had post-operative complications (anal fissure). Two (3.4%) patients had further haemorrhoidal surgery following THD. Conclusions: THD is a safe daycase procedure for symptomatic haemorrhoids of all grades. It is an effective treatment in the short term, but longer-term follow-up is required to assess its symptomatic benefit more formally.

1. Introduction

Symptomatic haemorrhoids arise due to pathological swelling, engorgement and/or traumatisation of the dense vascular network supplying otherwise normal anal cushions [1]. This typically leads to symptoms of prolapse and bleeding, with a number of other associated problems including pruritis ani and mucus discharge. They exist as one of the commonest anal pathologies yet despite this, treatment options are often sub-optimal.

Traditional outpatient therapeutic strategies include rubber-band ligation and injection sclerotherapy; surgical interventions include stapled haemorrhoidopexy and excisional haemorrhoidectomy, the latter of which is generally considered to represent the gold-standard [2]. More recently, doppler-guided transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation (THD) with rectal mucopexy has been gaining popularity as a minimally invasive alternative to more radical surgical options. This is purported to bring with it the advantages of reduced post-operative pain and a swifter return to normal daily living than excisional haemorrhoidectomy [3-5] and better success rates than rubberband ligation [6]. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy also results in less post-operative pain than excisional haemorrhoidectomy [7], but carries the small risk of potentially lifethreatening pelvic sepsis [8].

Doppler-guided THD utilises a purpose-designed doppler probe to identify the branches of the superior rectal artery that feed the haemorrhoidal plexus and subsequently ligate them [9]. When combined with mucopexy, the haemorrhoidal tissue can be dearterialised and restored to a more natural position within a single operation and without the need for excising any tissue.

Given the relative recency of the introduction of THD into mainstream practice, few studies report on outcomes following THD [10]. The aim of this retrospective study of consecutive patients undergoing THD by a single surgeon over a two-year period is to expand the evidence base by evaluating outcomes in terms of efficacy and safety of THD for all grades of symptomatic haemorrhoids.

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

All patients having THD performed by a single surgeon over a two-year period were included in this retrospective analysis. All grades of symptomatic haemorrhoids were included along with any number or type of previous haemorrhoidal treatments.

2.2. Surgical Procedure

A pre-operative enema was used for all patients. All procedures were performed under general anaesthesia in the lithotomy position, with intravenous metronidazole given. A pre-packaged single-use THD set (THD Ltd., Worcester, UK) was used containing a sliding proctoscope with doppler-probe for artery identification. Arterial ligation was performed via a figure-of-eight suture. The number of ligations performed was adjusted according to the number of doppler signals encountered. Mucopexies were performed as required.

2.3. Follow-Up

Patients were followed-up clinically by the surgical team in the outpatient clinic. They were questioned regarding any symptomatic improvement or any changes in symptom profile. Any post-operative complications were recorded and arrangements made for further follow-up if it was clinically indicated.

2.4. Data Collection

Data were obtained with the consent of the Audit Department at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Information was obtained from patients’ written notes and digital records. Data parameters were patient demographics, presenting symptoms, previous treatment, the number of THD ligations and mucopexies performed, length of follow-up, documented symptomatic benefit, post-operative complications, readmission within 30 days and whether any further haemorrhoidal therapy was required. The primary outcomes were identified as complication rate and symptomatic benefit.

3. Results

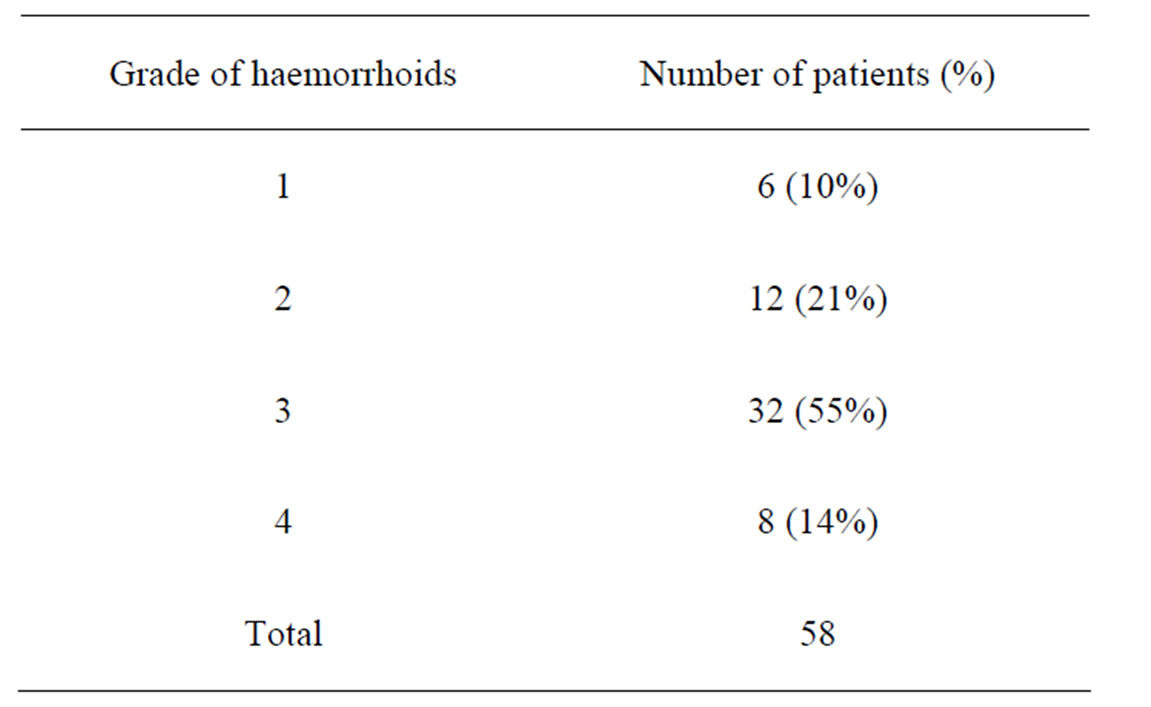

Fifty-eight consecutive patients (43 male, 15 female) were identified for inclusion in this study. Follow-up data post-operatively was available in 56/58 (96.6%) patients. Patients with all standard grades of haemorrhoid were included, with 55% having Grade 3 haemorrhoids (Table 1).

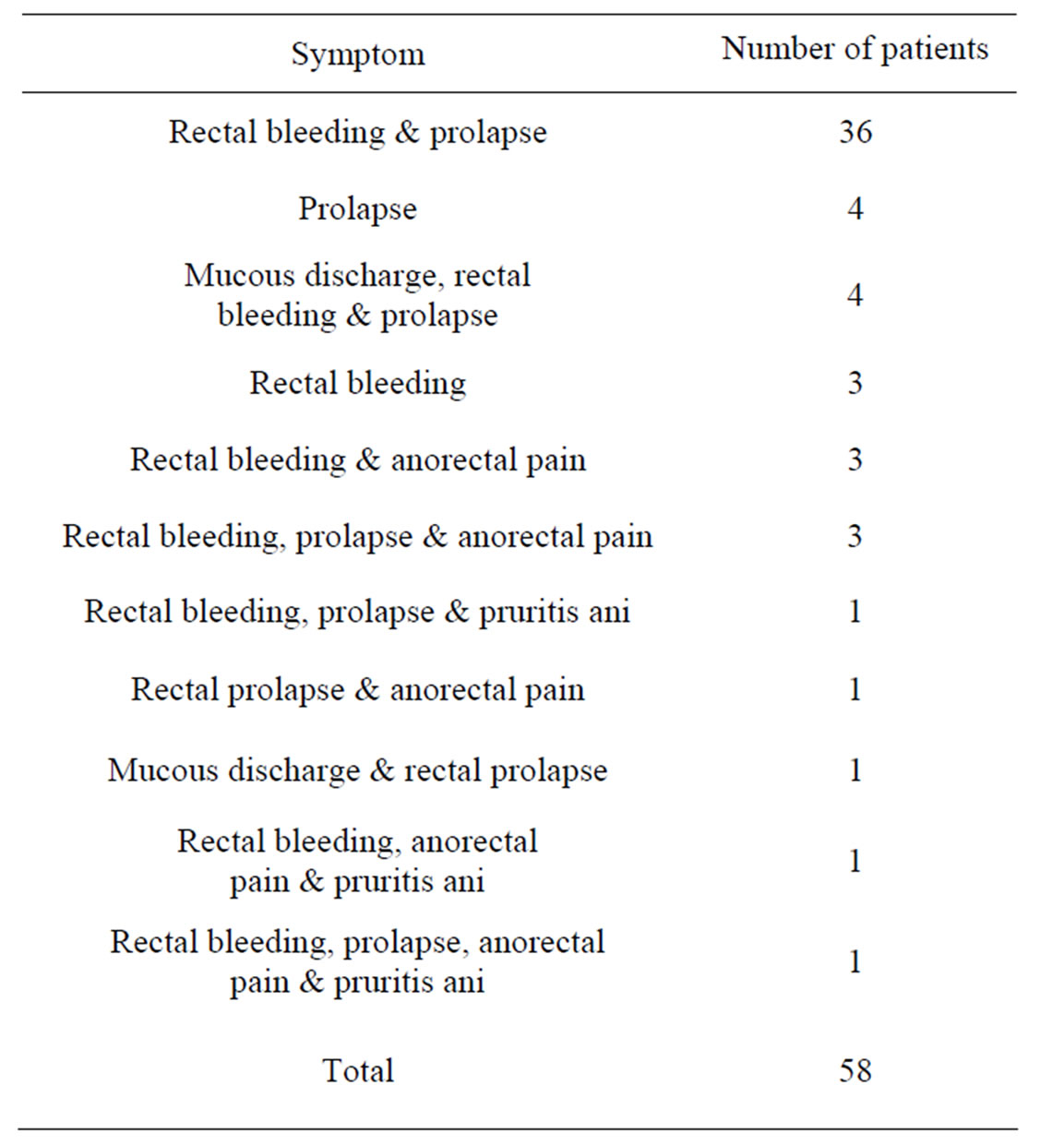

The majority of patients (79%) had undergone previous therapy, often in combination. The most common was rubber-band ligation (n = 39) but also injection sclerotherapy (n = 14), infrared coagulation (n = 1) and excisional haemorrhoidectomy at another institution (n = 3). The median number of previous haemorrhoidal treatments was 1 (range 0 to 4). Symptoms at presentation were variable and often multiple (Table 2); rectal bleeding and prolapse (n = 36) was the most common combination. Fifty-two (90%) patients presented with rectal bleeding.

The median number of THD ligations required was 7 (range 4 to 9). The median number of mucopexies performed was 3 (range 1 to 3). All operations (100%) were carried out as a day-case. No patients required return to theatre. Two patients developed an anal fissure (3.4%), with one of these requiring subsequent readmission overnight for analgesia.

Median follow-up was 10.5 weeks (range 1 to 48 weeks). Ninety-one percent of patients reported either resolution of symptoms or symptomatic improvement. Two patients (3.4%) requested further therapy, of which one had rubber band ligation performed in the outpatient clinic and the other a successful redo THD procedure.

Table 1. Frequency of grades of haemorrhoid.

Table 2. Frequency of symptom profiles.

4. Discussion

Although first described in 1995 [11], THD is a relatively novel therapy for haemorrhoids. This study sought to demonstrate that, in line with common hospital policies for the evaluation of a new service provision, THD is above all a safe practice. Additional data on efficacy for all grades of haemorrhoids and useful intraoperative data have also been identified.

The majority of studies relating to THD consider efficacy over safety, however some other authors do provide useful data on the risk of complications when using THD. In common with our data, Ratto et al. found none of their 170 patients complaining of chronic anal pain or incontinence in the follow-up period post-THD [12]. The same study reports the only complications to be postoperative bleeding requiring surgical haemostasis in 1.2% of cases. In the study by Sohn et al., the complications were thrombosed external haemorrhoid in 6% and anal fissure in 1.5% [13]. This compares to our overall complication rate of 3.4%, accounted for by 2 cases of anal fissure.

The overall complication rates of THD appear similar to those of stapled haemorrhoidopexy. However, stapled haemorrhoidopexy is associated with potential for faecal urgency, acute rectal obstruction, pelvic sepsis and even death [14-17]. When separated for early and late complications, equal rates of early complications exist between stapled haemorrhoidopexy and THD, but a greater incidence of late complications occurs with stapled haemorrhoidopexy [18]. The potential of clinically significant pelvic sepsis is a frequently raised criticism of stapled haemorrhoidopexy. The largest published review on the topic has identified 40 cases in the past 12 years which is acknowledged as an underestimate; of these cases, thirty-five required laparotomy with faecal diversion and there were four deaths [8]. This does not occur in conventional haemorrhoidectomy, where complications may include bleeding, anal seepage, delayed wound healing and anal stricture [19], with overall complication rates for conventional haemorrhoidectomy and stapled haemorrhoidopexy broadly comparable [20].

This study suggests a success rate of THD of 91%, when success is defined as a symptomatic improvement or resolution. This correlates with other work; Giordano et al. report 89% patient satisfaction rate at medium term follow-up in a small study [2], and rates of 91% and 92% for prevention of recurrence of prolapse and bleeding respectively at one year [11]. THD is frequently drawn into comparison with stapled haemorrhoidopexy as the only other surgical alternative to excisional haemorrhoidectomy, and data repeatedly suggest that there is no statistically significant difference in efficacy between the two [2-21], although data so far suggest that lifethreatening complications of THD have not yet been reported.

Patients with all grades of haemorrhoids were considered as candidates for THD in this study, although guidelines recommend excisional haemorrhoidectomy for Grade IV haemorrhoids [22]. Our results suggest that THD should be considered for patients with Grade IV haemorrhoids [23]. A further patient-dependent variable, the number of previous haemorrhoidal therapies, was also considered. No patients undergoing THD had previous stapled haemorrhoidopexy; however, 3 patients had a recurrence of their haemorrhoid symptoms following excisional haemorrhoidectomy at other institutions. These patients were treated successfully with THD and all achieved good symptomatic benefit with no complications or recurrence. To our knowledge, the use of THD following excisional haemorrhoidectomy has not previously been reported.

Despite the limitations of small sample size, limited length of follow-up and potential for observer bias, this study suggests that THD is safe and also efficacious in the short to medium term. The difficulty remains that THD is not as widely practiced as excisional haemorrhoidectomy and stapled haemorrhoidopexy, and absolute patient numbers are relatively low. Outcomes for 5-year follow-up after THD are beginning to emerge, and suggest an increased rate of recurrence when compared to 1 year outcomes [24]. It is hoped that the proposed United Kingdom multicentre, randomized trial of THD versus rubber band ligation in the treatment of symptomatic haemorrhoids (the HubBLe Trial [25]) will help to provide further valuable data.

5. Conclusion

THD is a safe daycase procedure, for which no life-threatening adverse outcomes have been reported to date. The results from this study support these observations and also suggest acceptable efficacy of THD over the short to medium term. It is a useful tool in the arsenal of haemorrhoidal therapies and with its acceptable safety and efficacy profile and minimal post-operative discomfort, it is an appropriate intervention to offer to patients with any grade of haemorrhoid and after previous attempted therapies (including previous excisional haemorrhoidectomy). Patients with haemorrhoids require a bespoke treatment approach, and THD appears to have a role within this setting.

REFERENCES

- J. A. Marx, R. S. Hockberger, R. M. Walls, et al., Eds, “Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice,” 6th Edition, Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2006, pp. 1509-1512.

- P. Giordano, P. Nastro, A. Davies and G. Gravante, “Prospective Evaluation of Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy versus Transanal Haemorrhoidal Dearterialisation for Stage II and III Haemorrhoids: Three-Year Outcomes,” Techniques in Coloproctology, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2011, pp. 67-73. doi:10.1007/s10151-010-0667-z

- H. Ortiz, J. Marzo and P. Armendariz, “Randomized Clinical Trial of Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy versus Conventional Diathermy Haemorrhoidectomy,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 89, No. 11, 2002, pp. 1376-1381. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02237.x

- N. Sohn, J. S. Aronoff, F. S. Cohen and M. A. Weinstein, “Transanal Hemorrhoidal Dearterialization Is an Alternative to Operative Hemorrhoidectomy,” The American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 182, No. 5, 2001, pp. 515-519. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(01)00759-0

- G. Felice, A. Privitera A, E. Ellul and M. Klaumann, “Doppler-Guided Hemorrhoidal Artery Ligation: An Alternative to Hemorrhoidectomy,” Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, Vol. 48, No. 11, 2005, pp. 2090-2093. doi:10.1007/s10350-005-0166-x

- V. Shanmugam, M. A. Thaha, K. S. Rabindranath, K. L. Campbell, R. J. Steele and M. A. Loudon, “Rubber Band Ligation versus Excisional Haemorrhoidectomy for Haemorrhoids,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2005, Article ID: CD005034.

- J. Burch, D. Epstein, A. B. Sari, H. Weatherly, D. Jayne, D. Fox and N. Woolacott, “Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy for the Treatment of Haemorrhoids: A Systematic Reviewk,” Colorectal Disease, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2009, pp. 233-243. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01638.x

- J. L. Faucheron, D. Voirin and J. Abba, “Rectal Perforation with Life-Threatening Peritonitis Following Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 99, No. 10, 2012, pp. 746-753. doi:10.1002/bjs.7833

- C. Ratto, A. Parello, L. Donisi, F. Litta, G. Zaccone and G. B. Doglietto, “Assessment of Haemorrhoidal Artery Network Using Colour Duplex Imaging and Clinical Implications,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 99, No. 1, 2012, pp. 112-118. doi:10.1002/bjs.7700

- P. Giordano, J. Overton, F. Madeddu, S. Zaman and G. Gravante, “Transanal Hemorrhoidal Dearterialization: A Systematic Review,” Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, Vol. 52, No. 9, 2009, pp. 1665-1671. doi:10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181af50f4

- K. Morinaga, K. Hasuda and T. Ikeda, “A Novel Therapy for Internal Hemorrhoids: Ligation of the Hemorrhoidal Artery with a Newly Devised Instrument (Moricorn) in Conjunction with a Doppler Flowmeter,” The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol. 90, No. 4, 1995, pp. 610-613.

- C. Ratto, L. Donisi, A. Parello, F. Litta and G. B. Doglietto, “Evaluation of Transanal Hemorrhoidal Dearterialization as a Minimally Invasive Therapeutic Approach to Hemorrhoids,” Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, Vol. 53, No. 5, 2010, pp. 803-811. doi:10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181cdafa7

- SPSS, SPSS version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, 2007.

- P. Grigoropoulos, V. Kalles, I. Papapanagiotou, A. Mekras, A. Argyrou, K. Papgeorgiou and A. Derian, “Early and Late Complications of Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy: A 6-Year Experience from a Single Surgical Clinic,” Techniques in Coloproctology, Vol. 15, No. S1, 2011, pp. S79-S81. doi:10.1007/s10151-011-0739-8

- M. J. Cheetham, N. J. Mortensen, P. O. Nystrom, M. A. Kamm and R. K. Phillips, “Persistent Pain and Faecal Urgency after Stapled Haemorrhoidectomy,” Lancet, Vol. 356, No. 9231, 2000, pp. 730-733. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02632-5

- S. Cipriani and M. Pescatori, “Acute Rectal Obstruction after PPH Stapled Haemorrhoidectomy,” Colorectal Disease, Vol. 4, No. 5, 2002, pp. 367-370. doi:10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00409.x

- J. E. Dowden, J. D. Stanley and R. A. Moore, “Obstructed Defecation after Stapled Hemorrhoidopexy: A Report of Four Cases,” The American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 76, No. 6, 2010, pp. 622-625.

- A. Infantino, D. F. Altomare, C. Bottini, M. Bonanno, S. Mancini, T. Yalti, P. Giamundo, J. Hoch, A. El Gaddal and C. Pagano, “Prospective Randomized Multicentre Study Comparing Stapler Haemorrhoidopexy with Doppler-Guided Transanal Haemorrhoid Dearterialization for Third-Degree Haemorrhoids,” Colorectal Disease, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2012, pp. 205-211. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02628.x

- A. Arezzo, V. Podzemny and M. Pescatori, “Surgical Management of Hemorrhoids. State of the Art,” Annali Italiani di Chirurgia, Vol. 82, No. 2, 2011, pp. 163-172.

- I. Goulimaris, I. Kanellos, E. Christoforidis, I. Mantzoros, C. Odisseos and D. Betsis, “Stapled Haemorrhoidectomy Compared with Milligan-Morgan Excision for the Treatment of Prolapsing Haemorrhoids: A Prospective Study,” European Journal of Surgery, Vol. 168, No. 11, 2002, pp. 621-625. doi:10.1080/11024150201680009

- M. S. Sajid, U. Parampalli, P. Whitehouse, P. Sains, M. R. McFall and M. K. Baig, “A Systematic Review Comparing Transanal Haemorrhoidal De-Arterialisation to Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy in the Management of Haemorrhoidal Disease,” Techniques in Coloproctology, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-8. doi:10.1007/s10151-011-0796-z

- A. G. Acheson and J. H. Scholefield, “Management of Haemorrhoids,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 336, No. 7640, 2008, pp. 380-383. doi:10.1136/bmj.39465.674745.80

- J. L. Faucheron, G. Poncet, D. Voirin, B. Badic and Y. Gangner, “Doppler-Guided Hemorrhoidal Artery Ligation and Rectoanal Repair (HAL-RAR) for the Treatment of Grade IV Hemorrhoids: Long-Term Results in 100 Consecutive Patients,” Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, Vol. 54, No. 2, 2011, pp. 226-231. doi:10.1007/DCR.0b013e318201d31c

- S. Avital, R. Inbar, E. Karin and R. Greenberg, “FiveYear Follow-Up of Doppler-Guided Hemorrhoidal Artery Ligation,” Techniques in Coloproctology, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2012, pp. 61-65. doi:10.1007/s10151-011-0801-6

- The HubBLe Trial: Haemorrhoidal Artery Ligation (HAL) versus Rubber Band Ligation (RBL) for haemorrhoids. http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN41394716/