International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol.06 No.03(2015), Article ID:54846,6 pages

10.4236/ijcm.2015.63022

Body Image and Meta-Worry as Mediators of Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Vahid Donyavi1, Mehdi Rabiei2, Masoud Nikfarjam3*, Behjat Mohmmad Nezhady4

1Department of Psychiatry, AJA University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Clinical Psychology, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Department of Psychiatry, Shahrekord University of Medical Science, Shahrekord, Iran

4Department of Psychology, Urmia Branch, Islamic Azad University, Urmia, Iran

Email: *nikmas140@gmail.com

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 28 February 2015; accepted 16 March 2015; published 19 March 2015

ABSTRACT

Objectives: Meta-worry and attitudes towards the body have been largely overlooked as potential risk factors for body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) despite theorizing that a negative body image may play a critical role in the development of this disorder. Participants: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the fit of a theoretical model specifying body image and meta-worry as mediators between cognitive, metacognitive beliefs and body dysmorphic disorder(BDD) in a nonclinical sample of 635 participants (304 male and 331 female). Results: The data supported the model, and meta-worry and body image significantly mediated the relationship between cognitive, metacognitive beliefs and BDD. These findings provide essential preliminary evidence that body image may represent a necessary but not sufficient risk factor for BDD and that treatment for BDD should consider targeting body-related pathology in addition to meta-worry. Conclusion: The model may prompt future research into body dysmorphic disorder.

Keywords:

Body Dysmorphic Disorder, Cognition, Metacognition, Body Image, Meta-Worry

1. Introduction

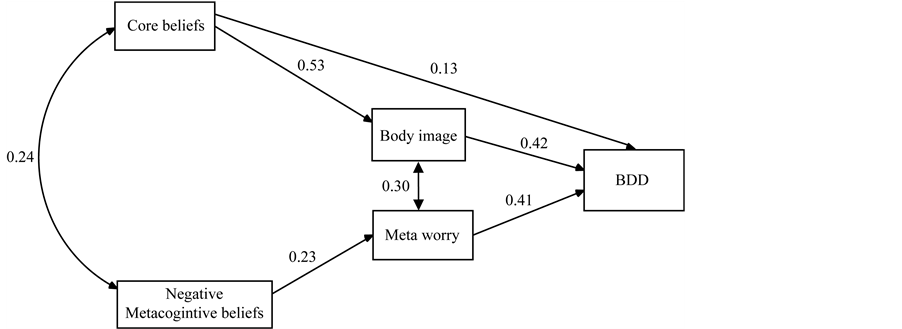

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is characterized by a preoccupation with one or more perceived defects or flaws in physical appearance that are not observable or appear slight to others, and by repetitive behaviors (e.g., mirror checking, excessive grooming, skin picking, or reassurance seeking) or mental acts (e.g., comparing one’s appearance with that of other people) in response to the appearance concerns. The preoccupation causes clinically significant distress and impairment in important areas of functioning [1] . A recent Dutch study demonstrates that 3% - 8% of the patients in dermatology and plastic surgery clinics of an academic hospital are to suffer from BDD [2] . Psychological and pharmacological treatments for BDD have received increasing attention in the past 10 years. Although psychological and pharmacological treatment approaches for BDD have been evaluated, the relative effectiveness of these two types of interventions has not been examined. Wiliams et al. [3] conducted a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and case series studies involving psychological (i.e., behavioral, cognitive-behavioral, cognitive) or medication therapies. Their findings support the effectiveness of both types of therapy, but suggest that cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) may be the most useful in the long term. Also, Rabiei et al. [4] reported that MCT was an effective treatment for BDD, with effected bing somewhat more pronounced on Thought-Fusion symptoms than on BDD symptoms. MCT deals with the way patients with BDD think and it assumes that the problem rests with inflexible and recurrent styles of thinking in response to negative thoughts, feelings and beliefs. In the Rabiei et al. [4] study, patients were taught that metacognitive beliefs, such as the belief that worry or rumination was an effective desirable coping strategy, were important factors contributing to the maintenance of BDD. However, metacognitive beliefs do not provide information that disconfirms negative beliefs or appraisals. Metacognitive regulation refers to a broad spectrum of executive functions, such as monitoring, planning, checking, attention and detection of errors in performance [5] . Metacognitive knowledge refers to the information individuals hold about their internal states and about coping strategies that impact on them [6] . Examples of metacognitive knowledge may include beliefs concerning the significance of particular types of thoughts (e.g. “Having thought X means I am weak”) and emotions (e.g. “I need to control my anxiety at all times”), and beliefs about cognitive competence (e.g. “I do not trust my problem-solving capabilities”). Examples of the information individuals hold about their own coping strategies that impact on internal states may include both positive (“Ruminating will help me find a solution”) and negative (“My checking behavior is making me lose my mind”) beliefs. In the metacognitive conceptualization of psychological dysfunction [7] , all the above constructs interact in maintaining maladaptive behavior. The Self- Regulatory Executive function (S-REF: [7] ) theory was the first to conceptualize the role of metacognition in the etiology and maintenance of psychological disturbances. In this theory, Wells and Matthews [7] argue that a common style of thinking across psychological disorders leads to dysfunction. They propose that psychological disturbance is maintained by a combination of perseverative thinking styles, maladaptive attentional routines, and dysfunctional behaviors. The S-REF theory has led to the development of disorder-specific models of depression [8] , generalized anxiety disorder [7] , obsessive-compulsive disorder [7] , and body dysmorphic disorder [4] . Cooper [9] suggested that patients with BDD do indeed engage in metacognitive processing in relation to their concerns with appearance. They report attempts to control, correct, appraise, and regulate their thinking in relation to images and also in relation to thoughts associated with their illness-related concerns. Thus, as suggested by Veale [10] , metacognition may be an important feature of information processing in BDD and may be one way in which the symptoms of the disorder are maintained. Theoretically, therefore, it may be an important dimension to be incorporated into a cognitive model of BDD. Further research is needed into the phenomena of metacognition, including its characteristics, functions, and role in the maintenance of the distressing symptoms of BDD. Imagery has been accorded a particularly important role in the maintenance of BDD, where mental images of the self are thought to be a particularly central feature of a cognitive conceptualization [10] . Body image is a complex concept that affects how people feel about themselves and how they behave. It has been defined as “the picture of our own body which we form in our mind, that is to say, the way in which the body appears to our-selves” [11] . A poor body image is a risk factor for developing body dysmorphic disorder. BDD is a body-image disorder characterized by persistent and intrusive preoccupations with an imagined or slight defect in one’s appearance. People with BDD can dislike any part of their body, although they often find fault with their hair, skin, nose, chest, or stomach. In reality, a perceived defect may be only a slight imperfection or nonexistent. But for someone with BDD, the flaw is significant and prominent, often causing severe emotional distress and difficulties in daily functioning. Although these studies have provided some basis about cognition, metacognition, and behavior in body dysmorphic disorder and shown that there is a relationship between them, there is need for a comprehensive model to link cognition, metacognition, body image and body dysmorphic disorder. In the current model we propose that the personal goals, values, and thoughts that increase an individual’s awareness of their appearance as well as the context of their daily experience play an important role in triggering worry about body dysmorphia. The first is activation of the cluster of schemas relevant to BDD. Types of schemas that characterize BDD: General threat (beliefs about probability and consequences of threats relevant to BDD), Personal vulnerability (beliefs about helplessness, inadequacy, lack of personal resources to cope), Intolerance of uncertainty (beliefs about the frequency, consequence, avoidance, and unacceptability of uncertain or ambiguous negative events). Beliefs about the uncontrollability and negative consequences of worry lead to Type II worry, or meta-worry, in which the individual becomes focused on trying to suppress or control worry and or the individual becomes focused on trying to mirror check, groom, or camouflage because of the associated rise in anxiety. Expanding theoretical conceptualizations of BDD to include the potential contribution of body image may also enhance understanding as to why this disorder manifests. It is clear from the literature that there exists a strong link between negative cognition and metacognition and BDD. While regulating negative cognition and metacognition explains one function of BDD, it does not seem to fully explain this disorder. Negative body image and metaworry has been proposed as potential mechanisms for understanding why BDD may occur in the context of negative cognition and metacognition, but research has yet to empirically evaluate the potential mediating effects of body image and meta-worry. The purpose of the current study was to test the theoretical notion that body image and meta-worry are mediators between negative cognition and metacognition and BDD (see Figure 1).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

The data for the Iranian sample were collected in 2014. The Iranian sample consisted of 635 participants (304 male and 331 female) attending medical and psychology clinics in Isfahan, Iran. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 59 years (M = 29.91; S.D. = 6.57). Multi-stage cluster sampling method was used to select the sample. Participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

2.2. Measures

The assessment tools in this study were the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for BDD, Body Dysmorphic Metacognitive Scale, Dysfunctional Attitude Scale form A, Cognitive Distortion Scale, Meta- Worry Questionnaire (MWQ) and ATQ and Compulsive behaviors spectrum scale.

2.2.1. Body Dysmorphic Metacognitive Scale, BDMCS; [12]

This measure consists of 25 items used to assess metacognitive errors or distortions related to body dysmorphic disorder. In order to obtain adequate face validity, a pool of items were used to construct BDMS from the data obtained in an earlier study (Rabiei et al., 2012) and transcripts of therapy sessions. The five factors identified (accounting for 83.8% of variance) reflected the following domains: 1) metacognitive control strategies, 2) thought-fusion, 3) positive metacognitive beliefs about emotional self-regulation, 4) positive metacognitive beliefs about cognitive self-regulation and 5) negative metacognitive beliefs about cognitive harm and uncontrollability. The convergent validity was supported by testing correlations between the BDMCS and the Yale-Brown

Figure 1. The model of body dysmorphic disorder.

Table 1. Participants characteristics (N = 635).

Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for BDD and TFI. The internal consistencies of the subscales were moderate to high, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.83 to 0.93. Responses to each item were required on a 4-point rating scale as follows: 1 (do not agree), 2 (agree slightly), 3 (agree moderately) and 4 (agree very much) [12] .

2.2.2. Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder BDD-YBOCS; [13]

This is a reliable and valid 12-item semi-structured clinician administered instrument that evaluates current BDD severity. It assesses BDD-related preoccupations, repetitive behaviors, insight, and avoidance [13] . The reliability and validity of the BDD-YBOCS Farsi version was demonstrated by Rabiei et al. [14] in both healthy and clinical samples. The alpha coefficients ranged from .78 to .93 for the BDD-YBOCS total score and for its subscales (preoccupations, repetitive behaviors) [14] .

2.2.3. The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale Form A [15]

This is a self-report scale designed to measure the presence and intensity of dysfunctional attitudes. The DAS-A consists of 40 items and each item consists of a statement and a 7-point Likert scale (7 = fully agree; 1 = fully disagree). Ten items are reversely coded (2, 6, 12, 17, 24, 29, 30, 35, 37 and 40). The total score is the sum of the 40-items with a range of 40 - 280. The higher the score, the more dysfunctional attitudes an individual possesses (Weissman and Beck, 1978). Internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and average item-total correlations of the DAS-A were satisfactory in different samples [16] .

2.2.4. Body Investment Scale (BIS; [17] )

The BIS is a 24-item scale assessing emotional investment in the body and consists of four unique subscales: feelings and attitudes towards the body (e.g., “I am satisfied with my appearance), comfort with physical touch (e.g., “I enjoy physical contact with other people”), body care (e.g., “I like to pamper by body”), and body protection (e.g., “I’m not afraid to engage in dangerous activities”). Research with the BIS has provided evidence of adequate reliability and validity with clinical and non-clinical adolescent samples [17] . Each of the four subscales consists of six items, responded to with a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Scores for each subscale are obtained by averaging item responses within each subscale and higher scores indicate more positive feelings about and investment in the body. The BIS subscales were used as indicators of the latent construct, body image, in the current study. Internal consistency estimates for each of the subscales within the current sample were: total scale a = 0.86; attitude/feeling a = 0.84; comfort with touch a = 0.74; body care a = 0.78; body protection a = 0.77 [17] .

2.2.5. Meta-Worry Questionnaire (MWQ)

Seven items reflecting the common danger themes in patients’ meta-worry were devised. Two response scales were constructed for each item, one designed to assess the frequency of each meta-worry and the other designed to assess the belief in each meta-worry at its time of occurrence. The frequency scale was a four-point scale ranging from (1 - 4) with each point labeled as follows: Never; sometimes; often; almost always. The belief scale ranged from 0 - 100 with anchor points labeled at each extreme as follows: I do not believe this thought at all, and I am completely convinced this thought is true. Subscale scores are obtained by summating responses to their respective items. Meta-worry was measured with a Spanish adaptation of one subscale of 7 items (between 1, “almost never”, and 4, “almost always”) from the Anxious Thoughts Inventory [18] . This Persian version has shown good reliability, construct validity and discriminative ability for BDD [4] .

2.3. Data Analysis

In order to examine the factor structure of the metacognitive-cognitive-behavioral model we conducted Structural Equation Modeling. For these analyses the Structural Equation Modeling program AMOS 5 was used [19] . Values of the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and the Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) close to 1 represent a good fit. Values of the Root Mean Square Residual (RMR) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) below .05 represent a good fit, and values less than .08 represent an acceptable fit.

3. Results

3.1. The Factor Structure of the Model

The factor structure of the model was examined by means of CFAs. Findings, reported in Figure 1 and Table 2, demonstrated that the model had overall fit to the data, and is closely related to the theoretical assumptions of the model.

We conduct an SEM analysis on the correlation between independent variables and to understand the indirect effects. These allow us to account for correlation and distinguish direct and indirect effects of our exogenous

Table 2. Model fit indices for the model of the metacognitive-cognitive for body dysmorphic disorder.

Note: N: number of participants; GFI: Goodness of Fit Index; AGFI: Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index; RMR: Root Mean Square Residual; SRMR: Standardized Root Mean Square Residual, AIC: The Akaike Information Criterion.

and endogenous variables on sense of community. We have investigated several model structures and find that the model presented in Figure 1 provides the best model fit. The model fit can be considered “good” in terms of goodness of fit (CMIN/DF = 1.27, GFI = 0.93, AGFI = 0.91 and RMSE 0.03).

Figure 1 showed the model structure which we finally obtained. Through this analysis, we find out the structure among BDD variables that could be explained to define the model. There are significant paths to cognition, significant paths to sense of meta-worry and significant paths to BDD. BDD is treated as observed, endogenous variable since we assume that it might be influenced by cognition, metacognition. All hypothesized paths were supported, all p < 0.05, there was a direct and significant effect of core beliefs on body image, standardized estimate = 0.53 (p < 0.01), there was a direct and significant effect of negative metacognitive beliefs on meta- worry, standardized estimate = 0.23 (p < 0.05), the standardized indirect effect of negative metacognitive beliefs on BDD through meta-worry was = 0.1 (p < 0.05), the standardized indirect effect of Core beliefs on BDD through body image was = 0.22 (p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

The intent of this study was to develop and validate the model for body dysmorphic disorder.

Findings of this study revealed that the metacognitive-cognitive model for body dysmorphic disorder had a clear factor structure, congruent with its theoretical conceptualization (see Figure 1 and Table 2).

The higher positive correlation and significance of this model and its factors with BDD reflect the acceptable validity of this model. This finding may be helpful to derive and illustrate the role of metacognitive beliefs about BDD together with other relevant cognitive constructs in a given episode. The distorted and faulty appraisal evident in pathological worry shares more similarities than differences with how individuals appraise other types of unwanted repetitive thoughts such as obsessions or depressive rumination. However, there is emerging evidence that certain metacognitive processes may be especially critical to the persistence of worry. A tendency to catastrophize, to believe that negative outcomes are likely to occur and will lead to significant negative effects in one’s life, and to perceive worry itself as a highly uncontrollable, disturbing, and dangerous process are metacognitive appraisals that are likely to contribute to an escalation of the worry process. Although empirical research relevant to this model is still preliminary, these early findings are encouraging for further exploration of the role of body image and metacognitive processing in BDD.

Given that individuals with BDD tend to appraise their worrisome thoughts as disturbing and associated with a greater likelihood of negative outcomes, this model is a natural extension of the previous hypothesis. According to the cognitive model illustrated in the previous hypothesis, we predict unsuccessful and futile efforts to control or suppress worry will paradoxically contribute to its persistence, in accord with Wegner’s ironic process theory of suppression [7] [18] . As predicted by model of the study, researchers have consistently found that BDD is characterized by a heightened subjective experience of worry as an uncontrollable process and any efforts at control prove futile and unproductive [3] [4] [20] . Despite their acknowledged inability to control worry, it is interesting that individuals with BDD are highly invested in continuing with their efforts toward gaining control over worry and unwanted repetitive thoughts [4] [12] [20] .

The present results are preliminary in nature. Clearly future studies are required to further establish the psychometric properties of the model. In particular, it would be necessary to determine the structure and reliability over time and with other samples. In addition, studies are required to examine the sensitivity of the model to treatment effects and recovery. The role of high levels of positive metacognitive beliefs in predisposing individuals to engage in BDD behaviors, and of negative metacognitive beliefs in maintaining problematic BDD behaviors, can also be investigated through longitudinal designs.

There are also limitations in this study, meaning that the results need to be interpreted with some caution. The use of a non-clinical sample may limit the generalizability of these findings to clinical populations as well as to populations that are diverse in age, socioeconomic status, and other demographic variables. The use of a non- clinical sample might also result in inflation of the associations among latent variables due to floor effects that can result from low levels of symptomology in most participants. Ultimately, only self-report measures are included for each construct. Future studies using multiple measures of each construct and with different response formats (e.g., clinician-rated, self-report, interview) may help improve these findings.

Despite these limitations, we believe that this model may be useful in providing a step towards the development of the metacognitive-cognitive conceptualization of BDD.

References

- Van Ameringen, M., Patterson, B. and Simpson, W. (2014) DSM-5 Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders: Cli- nical Implications of New Criteria. Depress Anxiety, 31, 487-493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.22259

- Vulink, N.C., Sigurdsson, V., Kon, M., Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.A., Westenberg, H.G. and Denys, D. (2006) Body Dysmorphic Disorder in 3% - 8% of Patients in Outpatient Dermatology and Plastic Surgery Clinics (Stoornis in de lichaamsbeleving bij 3-8% van de patienten op de poliklinieken Dermatologie en Plastische Chirurgie). Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde, 150, 97-100.

- Williams, J., Hadjistavropoulos, T. and Sharpe, D. (2006) A Meta-Analysis of Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 99-111.

- Rabiei, M., Mulkens, S., Kalantari, M., Molavi, H. and Bahrami, F. (2012) Metacognitive Therapy for Body Dysmor- phic Disorder Patients in Iran: Acceptability and Proof of Concept. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43, 724-729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.013

- Sheppard, L.C. (2002) Emotional Disorders and Metacognition: Innovative Cognitive Therapy. Psychological Medi- cine, 32, 750-752.

- Cooper, M. (2003) Emotional Disorders and Metacognition: Innovative Cognitive Therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42, 105-106.

- Wells, A. and Matthews, G. (1996) Modelling Cognition in Emotional Disorder: The S-REF Model. Behaviour Re- search and Therapy, 34, 881-888.

- Papageorgiou, C. and Wells, A. (2003) An Empirical Test of a Clinical Metacognitive Model of Rumination and De- pression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 261-273.

- Cooper, M. (2007) Metacognition in Body Dysmorphic Disorder―A Preliminary Exploration. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 21, 148-155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/088983907780851568

- Veale, D. (2004) Advances in a Cognitive Behavioural Model of Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Body Image, 1, 113-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00009-3

- Kostanski, M., Fisher, A. and Gullone, E. (2004) Current Conceptualisation of Body Image Dissatisfaction: Have We Got It Wrong? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 45, 1317-1325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00315.x

- Rabiei, M., Salahian, A., Bahrami, F. and Palahang, H. (2011) Construction and Standardization of the Body Dysmor- phic Metacognition Questionnaire. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, 21, 43-52.

- Phillips, K.A., Hollander, E., Rasmussen, S.A., Aronowitz, B.R., DeCaria, C. and Goodman, W.K. (1997) A Severity Rating Scale for Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Development, Reliability, and Validity of a Modified Version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 33, 17-22.

- Rabiei, M., Khormdel, K., Kalantari, K. and Molavi, H. (2010) Validity of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) in Students of the University of Isfahan. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 15, 343-350.

- Weissman, A. and Beck, A. (1978) Development and Validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A Preliminary In- vestigation. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Toronto, 27-31 March 1978, 1-13.

- Moore, M.T., Fresco, D.M., Segal, Z.V. and Brown, T.A. (2014) An Exploratory Analysis of the Factor Structure of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale-Form A (DAS). Assessment, 21, 570-579. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1073191114524272

- Osman, A., Gutierrez, P.M., Schweers, R., Fang, Q., Holguin-Mills, R.L. and Cashin, M. (2010) Psychometric Evaluation of the Body Investment Scale for Use with Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66, 259-276.

- Wells, A. (2000) Emotional Disorders and Metacognition: Innovative Cognitive Therapy. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 236 p.

- Gignac, G.E., Palmer, B., Bates, T. and Stough, C. (2006) Differences in Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Close- Fit Index Estimates Obtained from AMOS 4.0 and AMOS 5.0 via Full Information Maximum Likelihood No Imputa- tion: Corrections and Extension to Palmer et al. (2003). Australian Journal of Psychology, 58, 144-150.

- Cooper, M.J., Grocutt, E., Deepak, K. and Bailey, E. (2007) Metacognition in Anorexia Nervosa, Dieting and Non- Dieting Controls: A Preliminary Investigation. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46, 113-117.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.