Open Journal of Modern Linguistics

Vol.06 No.03(2016), Article ID:67180,12 pages

10.4236/ojml.2016.63022

The Effect of Task Based Language Teaching on Writing Skills of EFL Learners in Malaysia

Rai Zahoor Ahmed, Siti Jamilah Bt Bidin

School of Education and Modern Languages, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, Malaysia

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 6 May 2016; accepted 5 June 2016; published 8 June 2016

ABSTRACT

This quasi experimental study has validated the effectiveness of Task Based Language Teaching (TBLT) in promoting writing skills of EFL learners enrolled in undergraduate programs at public sector Malaysian universities. TBLT is emerging as an essential part of curricula in language pedagogies in several countries around the globe and advocated by prominent SLA researchers along with ELT practitioners. In current study research participants were divided into an experimental and a control group. The data were collected following a Mixed Method Research paradigm during pretest and posttest. A Paired Samples T-test was used to determine the statistical significance of the learners’ scores in pretest as compared to the posttest. The vast majority of the learners opined in their reflective journal that TBLT was the most interesting and a learner centered approach enabling learners to use their existing linguistic resources. The use of existing linguistic resources is a fundamental principle of TBLT as it leads the EFL learners to be fluent and confident users of English language both inside and outside the classroom in real life situations.

Keywords:

Task Based Language Teaching, Productive Skills, Second Language Acquisition English as Foreign Language, Mixed Method Research

1. Introduction

English language is the key to success in every walk of life as it is the lingua franca of our age and the most learned as well as taught language around the globe (Rahman, 2006, 2015) . It is a fact that English language has emerged as the most important and widely used language all over the world, so it is required to learn English everywhere in all continents. Due to its efficacy and being a guarantee of secure future, the number of English learners is increasing day by day in every part of the world. English language teaching has emerged as an independent discipline and we have ever increasing English language teaching methodologies (Pishghadam, 2011) . The current study focused on validating the effectiveness of Task Based Language Teaching (TBLT) to improve the writing skills of English language learners belonging from various nationalities at the language center established in all tertiary level institutions in Malaysia.

2. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the current study was to confirm the effectiveness of Task Based Language Teaching (TBLT) in promoting writing skills of the university undergraduates learning English language at the language centers in the public sector institutions of tertiary level in Malaysia. A quasi experimental research was designed in April, 2015 to determine the usefulness of TBLT in promoting writing skills of the language learners as compared to the traditional language teaching methodology based on Present-Practice-Production paradigm (Harmer, 2009) . All new international entrants in any public sector Malaysian university are required to prove their English language proficiency either through IELTS or they must belong from the countries having English language as a medium of instruction. Otherwise every international student in any Malaysian university is required to improve his/her English language skills from the established Language Centers in the Universities. The English language learners go through English Language Proficiency Test (ELPT) to prove their language skills. In other words, learners belonging from countries situated in the expanding circle of Kachru’s (1990) three concentric circles are required to prove their English language abilities in order to be a successful student of any Malaysian university.

3. Research Questions

The prime objective of the study was to determine the effect of TBLT on the writing skills of the English language learners of university undergraduates. The study constituted and focused on validating any improvement on the learners’ writing skills, in the first phase, by TBLT treatment at undergraduate level registrants. Secondly learners from the experimental group also presented their views about the TBLT treatment with respect to their previous schooling experience following Presentation-Practice-Production paradigm in ELT classrooms (Zainuddin, 2011) . Student feedback and perceptions about TBLT exposure was sought in order to determine their vision about TBLT treatment as compared to the traditional teaching methodology. To be more specific, current empirical study was designed to find out the answers of following research questions.

1) How does TBLT affect the learners’ second language writing skills?

2) What are the EFL learners’ perceptions about TBLT in improving L2 writing skills?

4. Significance of the Study

In a holistic view English is enjoying a status of the most prestigious language as compared to any other language in this world. It is due to the importance of communication in English as no nation can survive without sufficient knowledge of English in order to promote trade, commerce and imports/exports. Irrespective of nation, religion or any geographical location everyone is struggling to be dexterous in English language skills. Same is the case with the emergence of several language teaching methodologies (Zainuddin et al., 2011) . Being an ELT practitioner the researcher aspires to enable English language learners to get rid of erroneous English and to be confident users of English especially in higher education at any international university such as Universiti Utara Malaysia and many more in Malaysia providing quality education to the international students in several fields. Researcher believes that by validating the effectiveness of TBLT in improving writing skills by this study, language pedagogy would be one of the amazing aspirations both for the teacher and the taught. TBLT is a learner centered language teaching methodology and the teacher plays the role of a facilitator and not as the master of the show in the traditional language teaching methodologies (Ellis, 2009; Robinson, 2011; Willis & Willis, 2007; Carless, 2009 ; Samuda & Bygate, 2008 ).

5. Literature Review

Language is one of the basic characteristics of human beings; language categorizes Homo sapiens uniquely from all other animals. According to Crystal (2010) , “It is language, more than anything else, which makes us feel human”. Each society in this world has a particular language, and this unified language usage determines that speech community marking identity of the speakers. Language is an important tool and it has various functions but the most vital function of language is to communicate with fellow human beings (Pozzi, 2004) . There are four basic language skills such as listening, speaking, reading and writing. A child in any linguistic environment learns his/her mother tongue in this natural order and it is a fact that writing is the most complex skill to master (Ellis, 2003) .

Another division of language skills is the productive skills (speaking and writing) and receptive skills (listening and reading). Willis and Willis (2007) categorized speaking as an interpersonal skill and writing as the transactional skill. We all acquire mother tongue almost without any effort. When there is a case of learning a language other than one’s mother tongue, situation is different as compared to any individual mother tongue. Learning style refers to an individual’s favorite way to learn and utilize one’s natural abilities to focus on particular ways to learn in an idiosyncratic manner. Basically learning styles are two faceted subjects such as systematic versus unsystematic, reflective versus impulsive and inductive versus deductive. Every individual has certain style specific priorities marking their merits and demerits (Dörnyei, 2005) . Learning styles, can maneuver at any time, are not static or fixed for a long time as they are dependent on relative situations and tasks undertaken by the learners (Griffiths, 2008) . Almost same is the case with language teaching methods as Kumaravadivelu (2008) has differentiated language teaching methods in three main categories:

1) Language centered methods

2) Learner centered methods

3) Learning centered methods

Each language teaching method is based on specific syllabus depending upon the focus on the underlying assumptions as highlighted in the syllabus. In fact syllabus is at the center of any teaching-learning process and it plays a paramount role in ELT. For effective and result oriented ELT scenario a number of syllabuses have been devised based on certain assumptions and requirements of the target needs of the learners (Thakur, 2013) .

There are two major kinds of syllabuses such as product-oriented syllabuses and process-oriented syllabuses. Nunan (1988) describes that product oriented syllabuses are those where focus is on the end product i.e. knowledge which learners gain after classroom teaching. Process oriented syllabuses are those where emphasis is on the learning experience using analytic approach. Task based syllabus is an upgraded modification of communicative language teaching and it differs from other syllabi as it commences after needs analysis (Nunan, 2001) . Task based syllabus considers many perspectives of language learning before its execution. Task based syllabus is emerging as the most utilized syllabus in all the continents of the world due to its effectiveness and outcome in English language pedagogy (Pishghadam & Zabihi, 2012; Carless, 2009 ; Park, 2010; Rahimpour, 2008) .

6. Background of TBLT

Basically TBLT follows on the principles and effectiveness of experiential learning introduced by John Dewey (1859-1952) and real life situations are rehearsed in the language teaching classrooms (Ellis, 2009; Hu, 2013) . More recently in modern theories of learning TBLT is based on the constructive theory of learning. History of TBLT goes back to 1980s as it emerged out of the Communicational Language Teaching project in India by Prabhu (1987) . The rationale behind its origination is the lack of performance in the target language production and other limitations of the traditional language teaching methodologies based on the structural approach following PPP (Presentation-Practice-Production) paradigm. The PPP approach is based on the behaviorist school of learning and learners are presented with chunks of language focusing on the abstract grammatical principles and rote learning of the target language structures (Ellis, 2003; Long & Crookes, 1993) . Previously it was assumed that learners could only master a language if they memorized and practiced the grammar of the target language. It proved wrong in the long run as learners knowing only theoretical grammatical rules were not able to communicate fluently in the target language in real life situations (Krashen, 1985; Prabhu, 1987; Willis & Willis, 2007; Ellis, 2003) .

The role of the learner’s motivation, cognitive abilities and autonomy enjoy the central place in constructivism, which are also fundamental assumptions in TBLT (Robinson, 2011; Willis, 1996; Ellis, 2009; Bygate et al., 2001) . Wang (2011) asserts that constructivism emphasizes learners’ autonomy, reflectivity, personal involvement and active engagement of the learners in the process of learning; practically same is the case with TBLT principles. When a learner undertakes a communicative task, he is inclined to make use of his existing linguistic resources in order to achieve an outcome (Willis & Willis, 2007) . There is a concurrence both in TBLT and in the learning principles of constructivism (Ellis, 2003; Hu, 2013) . TBLT asserts that language is best learned when focus is on meaning and it is contrary to the concentration on form i.e. grammatical structures of the target language based on the traditional linguistic or structural syllabus (Ellis, 2003; Willis & Willis, 2007) . Dörnyei (2005) has illustrated that “language learning is ultimately a highly interpersonal enterprise, involving relationships between learners and teachers, therefore, understanding the psychology of these relationships and of the agents involved in them is half the battle.”

Skehan (1996) and Carless (2009) differentiated strong from weak forms of task based language teaching. The strong TBLT form focuses more on meaning making in real life scenarios along with authentic and accurate performance of the tasks. The weak form of TBLT accommodates more flexible tasks for communicative teaching and language pedagogy (Hu, 2013) . The roles performed by the language learners in TBLT are labeled as: participants, risk takers, listeners/speakers, storytellers, innovators and sequencers. They participate in group works or in pair/dyads during task cycle for successful L2 development.

The basic unit of a lesson in TBLT classroom is the task and various tasks are designed to facilitate the learners with real life communicative situations enabling them real communicators of the target language. It is a learner-centered approach, based on the constructivist school of learning and teacher plays the role of a facilitator of the communicative interaction among the learners (Ellis, 2009) . During TBLT a language learner plays a dynamic role in the whole process of language learning as he takes active part in interactive and communicative activities throughout the task performance cycle to achieve an outcome (Prabhu, 1987; Bygate et al., 2001; Skehan, 1998; Robinson, 2011; Ellis, 2003) . Samuda and Bygate (2008) defined task as “A task is a holistic activity which engages language use in order to achieve some nonlinguistic outcome while meeting a linguistic challenge, with the overall aim of promoting language learning, through process or product or both” (Samuda & Bygate, 2008: p. 69) .

Nunan (2004) has differentiated task classification as the pedagogical tasks and real life tasks. The pedagogical tasks mean the communicative activity performed in the classroom to achieve an outcome, basic purpose of pedagogical task is the rehearsal of real world all around. The real-world task means the real life interactive communication outside the classroom for example reserving an air ticket, job interviews and making new friends. The basic purpose of a task is not only to communicate but to achieve a purpose and an outcome while focusing primarily on pragmatic meaning (Ellis, 2009) . Figure 1 describes TBLT framework designed by Nunan (2004) .

Figure 1. Framework for TBLT by Nunan (2004: p. 25) .

Willis and Willis (2007) have distinguished tasks in a broader sense as the rehearsal tasks and the activation tasks. Rehearsal tasks assist the learners to perform anything which requires the learners to attempt outside classroom. These tasks are not exactly the same as the real-world situations but there is some kind of adaptation to fit in the classroom environment. Examples of rehearsal tasks are to search an advertisement in newspaper for a suitable employment or a job interview by a pair or group in the classroom. The activation tasks have nothing to do with real world situation and they are designed to stimulate and to improve integrated language skills. Here textbook adaptation by a skillful teacher facilitates the second language learners to improve target language learning (Ellis, 2003; Robinson, 2011) .

7. Research Methodology

Current study followed mixed method research paradigm as the research is categorized by the way it is designed to collect data and to analyze the data to reach the findings of that study. The research is called a mixed method research (MMR) if it collects data both quantitatively as well as qualitatively i.e. the data consisting on words, views, opinions, responses and numbers or numerical data. It is obvious that data produced by mixed method research (MMR) is more authenticated, replicable, valid and verifiable as compared to any other approach producing data singly. Creswell and Clark (2007: p. 5) define MMR as “it involves philosophical assumptions that guide the direction of the collection and analysis of data and the mixture of qualitative and quantitative data in a single study. Its central assertion is that the use of quantitative and qualitative approaches in combination provides a better understanding of research problems than either approach can do alone”.

MMR is supported by both type of data collection along with data analysis following qualitative as well as quantitative paradigms. Both inductive and deductive approaches are employed in MMR for data collection (Riazi & Candlin, 2014) . It is a kind of research, where the researchers focus on qualitative paradigm during one phase and follow quantitative paradigm at the other phase of the research. According to Zohrabi (2013) an MMR has more reliable and valid research instruments for data collection as compared to any other single paradigm. Current study was an example of a small scale MMR as the researcher started with the Pretest of the research participants of control and experimental group, followed by treatment of TBLT to the experimental group. Pretest and posttest were also administered for the control group being taught by traditional methodology. Reflective journals were utilized by the English language learners of the experimental group at University Utara Malaysia to find out their perceptions and feedback about the TBLT treatment. It can by concluded the MMR is just like conducting two mini-studies simultaneously within one main research for corroboration of the research findings (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003) .

8. Research Participants

The research participants were international students from different countries having different ethnographic backgrounds. One thing was common they all belonged from countries situated in the expanding circle of the Kachru’s (1990) three concentric circles. All the participants were enrolled in different undergraduate programs at a tertiary level institution and registered in Intensive English Language program to appear in the English Language Proficiency Test (ELPT) to be successful students by proving their proficiency in English language. The age group of the experimental group was from 19 to 22 years with a mean age of the group as 20.5 years. Almost same was the age group of the control group i.e. from 19 to 22 years with a mean age of the group as 21 years. In this way all the research participants from the experimental group and control group were homogenous in terms of their EFL background, admitted in university undergraduate program (BS programs) and in their age group. All students were in their first semester and new to university education. The experimental group comprised on a total of 14 participants (n = 14) including male and female students Research participants of control group were 16 (n = 16) during pretest and the posttest comprising on male as well as female students. The experimental group consisted on nine female and five male students. The control group consisted on ten female and six male students. Every student was willing and motivated to be the part of research process to improve his/her writing skills as they signed the consent form voluntarily to be part of the experimental research process.

9. Research Design

The study was designed to conduct the pretest at the onset of the research in the experimental group in April, 2015 followed by the TBLT treatment in class. The topic of the lesson was “Kinds of Essays” and the main focus of the experimental teaching was on improving learners’ descriptive writing skills. The posttest was conducted after treatment of TBLT to the research participants of the experimental group. Similarly the pretest and the posttest were administered in the control group without any treatment of TBLT. Data of learners’ writing skill during pretest and posttest of the experimental and control group were collected to determine any improvement in writing skill by introducing TBLT treatment. English language learners were given an essay for a writing task “Benefits of woman education” in order to collect their writing samples.

10. Data Analysis

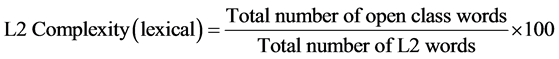

Learners’ second language complexity was measured with regard to L2 lexical diversity usage (Rahimpour, 2008; Salimi & Dadashpour, 2012; Ishikawa, 2006) , described in the formula below:

Table 1 shows improvement in Lexical Complexity between the pretest and posttest in learners’ L2 performance of the experimental group.

Table 1 provides evidence of improvement in L2 lexical complexity in writing skill with TBLT treatment as the difference in L2 complexity of posttest is +63.02 more than that in pretest. Table 1 is an evidence and answer to the research question one about the effect of TBLT on learners’ writing skills; same is the case in L2 fluency and L2 accuracy in following sections.

10.1. L2 Fluency Measure

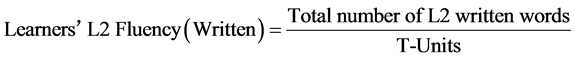

Skehan (1998) defined fluency as the learners’ capability to use language emphasizing meanings and using a variety of lexical items for a successful communication in second language. Ishikawa (2006) measured fluency of L2 written production as the number of words divided by T-Units. The main clauses were added to the subordinate clauses (attached or embedded in the main clause) to count as T-Units (Long, 1991; Salimi & Dadashpour, 2012) .

Table 1. Difference of L2 complexity during pretest and posttest in experimental group.

T-Units in this case mean total sum of main and subordinate clauses in learners’ L2 written sample (Ishikawa, 2006; Salimi & Dadashpour, 2012; Long, 1991) .

Table 2 presents difference of written L2 Fluency between Pretest and Posttest of the experimental group.

Table 2 illustrates improvement in L2 fluency measure (+27.79) of the experimental group in the posttest as compared to the pretest. The sum total of L2 fluency of the experimental group during pretest was 138.92 and it was improved to become 166.71 after TBLT treatment in posttest. Following subsection describes the difference and improvement in accuracy measure in writing skills of the experimental group.

10.2. L2 Accuracy

Accuracy in writing skill means the degree of correctness i.e. to what extent students write correct English. Skehan and Foster (1999: p. 77) defined accuracy as “ability to avoid error in performance, reflecting higher levels of control in the language as well as avoidance of such challenging structures that might provoke error”. Ellis (2003: p. 340) defined second language accuracy measure as, “the learner’s ability to produce error free target language”. It means how language written during L2 performance was accurate. In current study learners’ L2 accuracy was measured as error-free T-units divided by T-units. It means, only that T-unit was counted as error free T-units which was free from grammatical, syntactical and spelling error (Rahimpour, 2008; Ishikawa, 2006; Salimi & Dadashpour, 2012) . In simple words accuracy was measured by counting total number of error free clauses divided by the total number of clauses in the speech or written sample of the target language. The formula for calculating learners’ L2 accuracy is as below:

Table 3 describes difference and improvement in EFL learners’ accuracy measure during pretest and posttest from the experimental group.

Table 2. Difference in L2 Fluency of the Experimental group in pretest and posttest.

Table 3. Learners’ L2 accuracy during pretest and posttest of the experimental group.

Table 3 describes that the treatment of TBLT to the experimental group has increased L2 accuracy measure in writing skill from 8.42 to 10.66 i.e. an improvement in accuracy measure equal to +2.24.

In order to find out statistical significances in the scores of learners’ L2 performance in terms of complexity, accuracy and fluency, a Paired Samples T-test was utilized through SPSS version 20.0. Table 4 illustrates that there are significant differences in the complexity of experimental group scores from pretest scores (M = 59.65, SD = 6.82) to posttest (M = 64.15, SD = 5.26), t (13) = −5.55, p = 0.000 (two-tailed). The mean difference in two scores was −4.50 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −6.25 to −2.75. The Eta squared statistic (0.70) indicates a large effect size in the scores. It is a proof of the effectiveness of TBLT in improving writing skills. The results in Table 4 demonstrate that there are significant differences in the L2 fluency of experimental group scores from pretest scores (M = 9.92, SD = 1.10) as compared to that in posttest (M = 11.92, SD = 1.74), t (13) = −6.12, p = 0.000 (two-tailed). The mean difference in two scores is −1.99 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −2.70 to −1.29. The Eta squared statistic (0.74) indicates a large effect size. Similarly, there was significant difference in the accuracy of experimental group as compared to that in the pretest (M = 0.60, SD = 0.075) to that in posttest scores (M = 0.76, SD = 0.05), t (13) = −9.41, p =0.000 (two-tailed). The mean difference in two scores was −0.16 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −0.19 to −0.12. The Eta squared statistics (0.87) indicated a large effect size i.e. the effect of TBLT on learners’ writing skills as shown in Table 4. A Paired Samples T-test was also carried out to determine the significant differences among English language Complexity, Fluency and Accuracy measures of the control group during pretest and posttest. Table 4 illustrates L2 performance of experimental and control groups comprehensively.

It is evident that by comparing the Eta squared statistics i.e. effect sizes of measures of L2 complexity, fluency and accuracy of the experimental and the control group, the experimental group performed holistically better than the control group in their L2 writing skill as illustrated in Table 4. There were no significant differences to mark any improvement in the scores of control group as compared during pretest and posttest in their writing skills. The results in Table 4 indicate that there are no significant differences in the pretest scores and posttest scores of L2 performance triad within the control group but in case of the experimental group there are statistical significances in the scores of L2 performance indicators, complexity, fluency and accuracy.

Table 4. Paired samples t-test.

11. Student Feedback of TBLT Treatment

Students of the experimental group provided feedback to express their views about TBLT treatment and to determine answer of second research question in present study. Student feedback was based on Likert scale continuum from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” ranging from 1 to 5. The feedback was obtained in order to find out research participants’ opinion about three subcategories:

(a) Student (b) Materials (c) Teacher

Respondents were also provided with facility to write down their suggestions and comments about the experimental teaching based on TBLT. Few students opined TBLT as an interesting way of learning and teaching. While some wrote teacher was very punctual and others wrote TBLT, a new method of teaching. Table 5 presents students’ response in reflective journal.

It is clear that most of the students’ feedback was in the favor of the effectiveness of TBLT and their perceptions inclined towards agree and strongly agree with the statements as compared to strongly disagree and disagree in Table 5. This marked their liking about TBLT treatment and a proof that TBLT is a learner centered language teaching approach.

12. Conclusion

The main purpose of current study was to determine the effect of TBLT on writing skills of the university undergraduates belonging for EFL contexts and aspiring for higher studies in Malaysian Universities (Kachru, 1990) . The experimental teaching was conducted in April, 2015 and there was an improvement in L2 performance indicators in terms of L2 complexity, fluency and accuracy measures of the research participants from the experimental group as compared to the language learners from the control group as depicted in the tables illustrated above. The researcher learned and observed a lot during experimental teaching to the international students. It was anticipated optimistically that researcher would improve during the conduct of further research in TBLT for a comprehensive study to validate the effectiveness of TBLT in improving productive skills. The study provided hands on experience of the TBLT treatment and motivation for the researcher to corroborate effectiveness of TBLT in any other context (Skehan, 1996; Carless, 2009; Ellis, 2009; Willis & Willis, 2007;

Table 5. Students’ feedback from the Experimental group about TBLT (n = 14).

F*= Frequencies. P**= Percentage.

Rahimpour, 2008) . It benefitted the researcher to validate the research instruments to be utilized for further replication in any other location and ELT settings as the research exposure was pragmatic and interesting as well.

Cite this paper

Rai Zahoor Ahmed,Siti Jamilah Bt Bidin, (2016) The Effect of Task Based Language Teaching on Writing Skills of EFL Learners in Malaysia. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics,06,207-218. doi: 10.4236/ojml.2016.63022

References

- 1. Bygate, M. et al. (Eds.) (2001). Researching Pedagogic Tasks: Second Language Learning, Teaching and Testing. Harlow: Longman.

- 2. Carless, D. (2009). Revisiting the TBLT versus PPP Debate: Voices from Hong Kong. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 19, 49-66.

- 3. Creswell, J.W., & Clark, P. L. (2007) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- 4. Crystal, D. (2010). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge, UK: Amazon Publishers.

- 5. Dornyei, Z. (2005). The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- 6. Ellis, R. (2003). Task-Based Language Learning and Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 7. Ellis, R. (2009). Task-Based Language Teaching: Sorting out the Misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 19, 221-246.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00231.x - 8. Griffiths, C. (Ed.). (2008). Lessons from Good Language Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511497667 - 9. Harmer, J. (2009). The Practice of English Language Teaching (4th ed.). Harlow: Longman.

- 10. Hu, R. (2013). Task Based Language Teaching: Responses from Chinese Teachers of English. TESL-EJ, 16, 1-21.

- 11. Ishikawa, T. (2006). The Effect of Task Complexity and Language Proficiency on Task Based Language Performance. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 3, 193-225.

- 12. Kachru, B. B. (1990). The Alchemy of English: The Spread, Functions and Models of Non-Native Englishes. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- 13. Krashen, S. D. (1985). The Input Hypothesis: Issues and implications. Beverly Hills, CA: Laredo Publishing Company.

- 14. Kumaravadivelu, B. (2008). Understanding Language Teaching: From Method to Post method. London: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- 15. Long, M. (1991). Focus on Form: A Design Feature in Language Teaching Methodology. In K. de Bot, R. Ginsberg, & C. Kramsch (Eds.), Foreign Language Research in Cross-Cultural Perspective (pp. 39-52). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1075/sibil.2.07lon - 16. Long, M., & G. Crookes (1993). Units of Analysis in Syllabus Design: The Case for Task. In G. Crookes, & S. Gass (Eds.), Tasks in Language Learning (pp. 9-54). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- 17. Nunan, D. (1988). Syllabus Design. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 18. Nunan, D. (2001). Second Language Acquisition. In R. Carter, & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge Guide to Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (pp. 87-92). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511667206.013 - 19. Nunan, D. (2004). Task-Based Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667336 - 20. Park, S. (2010). The Influence of Pretask Instructions and Pretask Planning on Focus on Form during Korean EFL Task-Based Interaction. Language Teaching Research, 14, 9-26.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1362168809346491 - 21. Pishghadam, R, & Zabihi, R. (2012). Life Syllabus: A New Research Agenda in English Language Teaching. Perspectives (TESOL Arabia), 19, 23-27.

- 22. Pishghadam, R. (2011). Introducing Applied ELT as a New Approach in Second/Foreign Language Studies. Iranian EFL Journal, 7, 8-14.

- 23. Pozzi, D. C. (2004). Forms and Functions in Language: Morphology, Syntax. Houston, TX: College of Education, University of Houston.

- 24. Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second Language Pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 25. Rahimpour, M. (2008). Implementation of Task-Based Approaches to Language Teaching. Pazhuhesh-e Zabanhaye Khareji, No. 41, 45-61.

- 26. Rahman, T. (2006). Language Policy, Multilingualism and Language Vitality in Pakistan. Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs, 175, 73.

- 27. Rahman, T. (2015). A History of Pakistani Literature in English (1947-1988). Islamabad, Pakistan: Oxford University Press.

- 28. Riazi, A. M., & Candlin, N. C. (2014). Mixed-Methods Research in Language Teaching and Learning: Opportunities, Issues and Challenges. Language Teaching, 47, 135-173.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444813000505 - 29. Robinson, P. (2011). Task-Based Language Learning. Ann Arbor, MI: Language Learning Research Club, University of Michigan.

- 30. Salimi, A., & Dadashpour, S. (2012). Task Complexity and Language Production Dilemmas. Procedia, 46, 643-652.

- 31. Samuda, V., & Bygate, M. (2008). Tasks in Second Language Learning. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9780230596429 - 32. Skehan, P. (1996). Second Language Acquisition Research and Task Based Instruction. In J. Willis, & D. Willis (Eds.), Challenge and Change in Language Teaching (pp. 17-30). Oxford: Heinemann.

- 33. Skehan, P. (1998). A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 34. Skehan, P., & Foster, P. (1999). The Influence of Task Structure and Processing Conditions on Narrative Retellings. Language Learning, 49, 93-120.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00071 - 35. Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.) (2003). The Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- 36. Thakur, K. R. (2013). Delineation of English Language Teaching Syllabi and Its Implications. The Criterion: An International Journal in English, 4, 205-214.

- 37. Wang, P. (2011). Constructivism and Learner Autonomy in Foreign Language Teaching and Learning: To What Extent Does Theory Inform Practice? Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 1, 273-277.

- 38. Willis, D., & Willis, J. (2007). Doing Task-Based Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 39. Willis, J. (1996). A Framework for Task-Based Learning. Harlow: Longman.

- 40. Zainuddin, H., Yahya, N., & Morales-Jones, C. A. (2011). Methods/Approaches of Teaching ESOL: A Historical Overview. In G. Botsford, & D. M. LaBudda (Eds.), Fundamentals of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages in K-12 Mainstream Classrooms (pp. 63-64). Dubuque: Kendall Hunt.

- 41. Zohrabi, M. (2013). Mixed Method Research: Instruments, Validity, Reliability and Reporting Findings. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3, 254-262.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.2.254-262