Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.4 No.2(2014), Article ID:42830,12 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2014.42015

Education is the key to protecting children against smoking: What parents think and do

School of Nursing, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada

Email: ssmall@mun.ca

Copyright © 2014 S. P. Small, A. L. Brennan-Hunter. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property S. P. Small, A. L. Brennan-Hunter. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received 16 November 2013; revised 6 January 2014; accepted 27 January 2014

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to examine parents’ communication with their children about the topic of smoking. A qualitative descriptive design was used. Twenty-nine parents who lived in rural communities and who had children in kindergarten to Grade 6 were interviewed. The data were analyzed for themes. A large majority of parents communicated with their children about smoking through verbal interaction, using any one of three approaches: discussing smoking with their children, telling their children about smoking, or acknowledging their children’s understanding of smoking. Those parents also had shown disapproval of smoking, which took different forms and varied from explicit messages in their verbal communication to implicit messages in their behaviours. Three parents had not verbally communicated at all with their children about smoking. Overall, the parents’ communication patterns with their children varied in terms of quality and coherence with recommendations in the literature.

KEYWORDS

Smoking Prevention; Tobacco Education; Health Promotion; Protection; Pre-Adolescent Children; Parental Education

1. INTRODUCTION

Smoking continues to be a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in many countries world-wide [1]. It affects people throughout the life span. Smoking in childhood impairs lung growth and pulmonary function, causes symptoms of asthma, and starts the damage that leads to cardiovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [2,3]. Nearly 90% of adult daily cigarette smokers begin smoking before 18 years of age [3]. Often tobacco dependence occurs rapidly and can develop after only very low exposure to nicotine. Indeed, tobacco dependence typically begins as a condition in youth [4,5]. Early dependence is associated with continuing and heavy smoking in adulthood [3,6]. Smoking in youth also is associated with alcohol and illicit drug use [7] and is considered a risk factor for those substances [8].

Although the prevalence of smoking among youths has declined in some economically-advantaged countries in recent years, smoking continues to be an important public health concern and has been described as a pediatric epidemic globally [3]. In Canada, the overall rate of cigarette smoking among 15 to 19 year olds is 12% [9]; among 11 to 14 year olds, about 15% have tried smoking a cigarette [7]. Many youths engage in forms of tobacco other than cigarettes, including pipe, cigar, and chewtobacco [7,9], and use more than one product concurrently [10]. Therefore, the actual use of tobacco among youths is higher than cigarette smoking rates alone reveal. Further, smoking rates tend to be higher in rural compared to metropolitan settings [11-13]; this also is the case for youths, more specifically [14,15]. Therefore, the rate of adolescent smoking in rural communities may be higher than national statistics suggest.

Smoking among youth is a complex behaviour, determined by any of a variety of factors including biological, psychosocial, and environmental factors. These factors can function as protection against smoking or as risk for it [3]. One factor identified in the literature as potentially protective is parental communication with children about the behaviour [16-19]. Yet, little is known about parental smoking-specific communication with young and preadolescent children. Most studies carried out have been (a) about parental communication with adolescents; (b) from the children’s, not parents’, perspectives; and (c) narrow in scope, such as frequency of parental communication about smoking, without a comprehensive examination of the nature of the communication.

In one study of parents of school-age and pre-adolescent children, however, it was noted that generally parents talked with their children about smoking, but varied in how they communicated, the extent of their communication, and the nature of the messages they gave [20]. Some parents discussed smoking with their children using an open, engaging style so that there was a two-way exchange of ideas. Those parents started talking about smoking when their children were young, took advantage of everyday opportunities to discuss the topic, addressed the topic regularly, and were comprehensive in their discussions, giving messages about health and influencing factors. Other parents used directive, one-way communication to convey to their children their thoughts about smoking or had little or nothing to say to their children about smoking. More research is required to further examine communication approaches that parents take with their children about smoking. That study was carried out in an urban centre. The purpose of this study therefore was to elaborate on the findings of that study by examining the smoking-specific communication of parents who reside in rural areas. A more complete understanding of parental communication could inform smoking prevention interventions for parents. Such interventions may be particularly important for parents in rural communities where smoking rates generally are higher. Because most children who smoke begin in the adolescent period, it would be prudent for parents to take preventive actions before then as adolescence may be a late point to start. Therefore, the following question was addressed in this study: What communication approaches do parents in rural communities take with their school-age preadolescent children about the topic of smoking?

2. METHOD

The study was approved by a university research ethics committee. It took place in a rural area in Eastern Canada. Of the 29 participants, 28 were from seven small town and rural communities with populations ranging from approximately 225 to 3200 people. Five of the communities had populations of less than 1000 people. Information about the residence of one participant is missing. Because the participants were located at a distance from the investigators and the study took place by telephone, informed consent was verbal. Given the dearth of research relevant to the research question, a qualitative descriptive design was used to gain an understanding of parental smoking-specific communication from the perspective of parents themselves.

2.1. Sample

The participants were recruited through (a) study brochures sent home to parents of elementary level students in rural schools and (b) nominated sampling whereby participants who were in the study identified other potential participants. The purposive sample consisted of 23 mothers and six fathers who had at least one child in kindergarten to Grade 6 and who contacted the first author to express an interest in the study. There were four mother-father pairs. The parents had from 1 to 3 children with the majority (62%) having two children. The referent children ranged from 5 to 12 years old and were about equally divided between boys and girls.

Twenty-three parents were non-smokers: nine mothers and four fathers had never smoked and 10 mothers formerly smoked. Four mothers and two fathers currently smoked. Twenty-five parents lived with a spouse or partner; four were single. Twenty-six parents had at least some university or college education; three had high school education or less. Twelve, 18, and 5 parents were classified as having high (>$89,000), middle ($30,000 - $89,000), and low (<$30,000) household income (Canadian), respectively. Occupations varied from professional to technical and clerical skills and unskilled sales, services, and labour. There were two stay-at-home and three unemployed mothers.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected through semi-structured telephone interviews. A detailed interview guide was used to encourage the parents to discuss their communication with their children about smoking and to ensure complete data. Broad open-ended questions were used, with more specific questions to probe as needed for details, for example; Is smoking a topic that has been approached in your family with (child)? How has the topic come up (by whom, when)? Can you think of a specific time when (child) talked about smoking or asked questions about it (describe the situation)? Have you ever seen (child) pretend to smoke (describe the situation)? How did you feel about that? Did you say or do anything? What is the best way to prevent children from smoking? Parents were interviewed privately. Those from the same family were interviewed separately. The interviews lasted approximately 30 to 45 minutes, were audio-recorded, and were transcribed verbatim to form the narrative for data analysis. One participant was interviewed a second time to add further detail to her story.

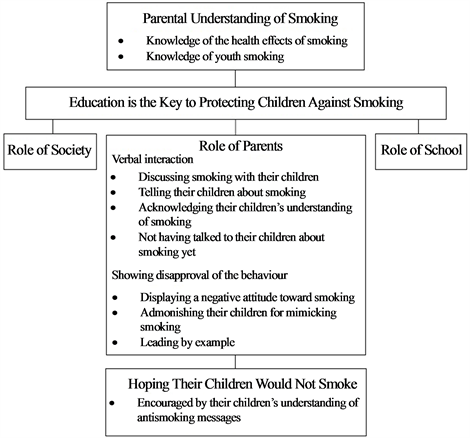

Data collection and beginning analysis occurred concurrently by the first author and thoughts on the data were used to inform subsequent interviews. Data collection occurred until there were 29 parents in the study, at which time there were variation and replication in the information provided and no new information was arising from the interviews. Data analysis was conducted separately by the two investigators, with meetings to discuss and finalize the results. The approach was conceptual ordering, as proposed by Strauss and Corbin [21], which refers to a method of generating themes and associated relationships from qualitative data. Consistent with that approach, the procedures used were coding, making comparisons, writing memos, and diagramming. Open, sentence-by-sentence coding was used to identify concepts and their characteristics. Incidents in the data and resulting concepts were compared, using the constant comparative method, for similarities and differences both within and across interviews. Concepts that were similar were combined to form the final themes. Memos were written to help think about and determine the concepts and themes and variation within and relationships among them. Diagrams were drawn to visualize the themes and relationships and resulted in the model depicted in Figure 1. Direct quotations from the participants were used to substantiate the themes (note: pseudonyms have been assigned to multi-word quotations).

3. FINDINGS

The parents in this study thought that “education is the key” (BF) to protecting children against smoking; this represents the main theme derived from the data (see Figure 1). Their ideas about education were influenced by their apt understanding of smoking. They thought that parents, society, and schools have roles to play, with antismoking information from “various sources” being important to reinforcing the message. To educate their children, therefore, a large majority of the parents communicated with them about smoking through verbal interaction. In contrast, despite the value they had placed on education as a preventive measure for youth smoking, some parents in this study had not verbally interacted at all with their children about smoking up to that point in the child’s development. Many parents also had sent antismoking messages to their children through some form of disapproval of the behaviour. All parents were hoping that their children would not smoke. Parents who interacted verbally with their children were encouraged by their children’s understanding of antismoking messages.

3.1. Parental Understanding of Smoking

The parents had knowledge of the health effects of smoking and knowledge of youth smoking that are consistent with what is known about smoking. The harmfulness of smoking coupled with the vulnerability of youth to the behaviour influenced the parents to think that “education is the key” (BF) to protecting children against smoking. “I see it as an educational thing.” (CE) “Educate them ... and hope that ... it’ll sink in and they won’t do it.” (MY).

Knowledge of the health effects of smoking. The

Figure 1. Model depicting what parents think and do in relation to smoking prevention. Parents had a good understanding of smoking which influenced their perception that education is the key to protecting children against smoking and involves parents, society, and schools. Parents communicated with their children through verbal interaction and showing disapproval and were hoping their children would not smoke.

parents knew that smoking causes addiction, general poor health, and serious illnesses. They did not want their children exposed to such health risks. As a parent who smoked commented, “I don’t want them to ... be addicted to smoking like I am. I know I’m putting my health at risk and stuff and I would never want that for my children.” (AG) Although some of the parents had not talked much or had not talked at all with their children about smoking, all thought that children should know about health effects in an effort to deter them from smoking.

Parents’ awareness of the health effects of smoking was the result of general widespread knowledge about smoking. For many parents, this awareness was increased by personal experience in being addicted or having other health effects as a smoker or former smoker or in having family members with such health consequences. That smoking is “a slow suicide” (SV) was reflected in the opinion of many of the parents. Smokers acknowledged the paradox in their situation, that is, smoking while knowing “all the downsides of it” (NW) and knowing that it is “a dangerous thing and ... very, very harmful to people” (FG). They attributed their continuing smoking to their addiction.

Once you try it you kind of get addicted to it and then, you know, it continues on from there, I guess, and keep smoking and keep smoking and then ... it’s a real bad addiction and it’s hard to give it up. Right. I know. I tried it and I just can’t do it. (FG)

A former smoker said, “It [quitting] was the hardest thing I ever had to do.” (OT) Another former smoker talked about how, despite being addicted, she quit smoking because of the health effects she was experiencing. “I got sick and tired [of] getting stuff up from my throat ... you cough it up. ... I hated that ... I used to be out of breath and ... not being able to do stuff.” (BV) A father who had never smoked talked about how both his grandfather and father had serious heart disease from smoking and his father also had lung disease. “My dad has had a quadruple by-pass. ... He’s not working anymore because of his lungs. ... not going to capacity anymore. He finds it difficult to breathe and stuff.” (PS)

Knowledge of youth smoking. Parents knew that children are at risk for smoking, especially adolescents but also younger children. Within their own communities, they had seen adolescents smoking and some had seen pre-adolescents smoking. Some parents personally knew adolescents who smoked: their own relatives, such as a nephew, or their children’s friends. “Our daughter who’s 13 would have had a few friends that ... smoked ... friends that were a bit older than her.” (LA) Parents who currently smoked or who had smoked had begun in adolescence, but some had tried smoking even in preadolescence. “I think I had my first cigarette at [age] 9. ... It was probably 12 or 13 [that] I decided I was a smoker.” (NW)

Parents thought that children are susceptible to smoking because of such factors as “curiosity”, the need to feel “cool” or “fit in” as adolescents, and exposure to the behavior, especially from parents and peers. Many parents thought that their own experimenting with or initiation of smoking was the direct result of having parents or friends who smoked, or a combination of both. As a former smoker said, “My parents did it. They were my role models, my first role models you could say, and then my peers smoked.” (JC) Having parents who smoked also made access to cigarettes easy. Some parents commented that they had surreptitiously obtained cigarettes at home when they were growing up. A parent who had begun smoking at age 13 reflected, “I don’t know if it would have turned out differently had I been able not to steal my mother’s cigarettes.” (AG) Parents who smoked acknowledged that they were a potentially negative influence for their children and were concerned about that.

I am petrified that my daughter is going to follow my footsteps ... I feel really bad. It makes me feel ashamed ... I don’t smoke where she is at ... I smoke outside. I cringe every time I do it and I always say, you know, I got to quit smoking because I don’t want her to see that, because her seeing me is potential for her to want to do it. Cause I don’t want her to think that it’s cool, cause it is not. (NW).

Interestingly, 4 of the 6 parents in this study who smoked hid their smoking from their children in an effort to avoid influencing them; they were “closet” smokers.

Parents thought that education is important to counteract parental, peer, and other influences. Consequently, although some parents had not yet talked with their school-age children about smoking, generally the parents thought that children should learn about the health effects of smoking when they are young and “impressionable” as opposed to waiting until the adolescent years, at which point they might already be smoking. In the words of one parent, “Talk to them ... instead of waiting to have to deal with it.” (RU)

3.2. Role of Parents

The parents in this study thought that parents have an important role to play in educating their children about smoking and many had engaged in measures to that effect. Twenty-six of the parents had verbally interacted with their children about smoking; although, the quality of the verbal interaction varied among the parents. In addition, those parents had shown disapproval of smoking, which took different forms and varied from explicit messages in their verbal communication to implicit messages in their behaviours. Three parents had not verbally interacted with their children about smoking and also had not shown explicit disapproval.

Parental verbal interaction with their children. The parents who verbally interacted with their children about smoking did so by using any one of three approaches: discussing smoking with their children, telling their children about smoking, or acknowledging their children’s understanding of smoking. The parents who had not verbally interacted with their children are represented by the category, not having talked to their children about smoking yet. There was no distinction among the four communication patterns with respect to smoking status. Each group had at least one parent who currently smoked, formerly smoked, and had never smoked. There also were no consistent separations among the groups on the basis of socio-demographic characteristics. However, a pattern was noted among the group of parents who were discussing smoking with their children; all were college or university graduates, all had professional occupations, and all had middle or high household incomes. The other groups tended to have more diversity within them in terms of socio-demographic characteristics.

Discussing smoking with their children. A small group of parents deliberately engaged their children in discussions in which they, individually or with the other parent, talked with their children about smoking. These parents consistently acted on opportunities as they arose to discuss some aspect of smoking; for example, the parent or child seeing a person in their community smoking, a question from the child about smoking, or a school activity about smoking were used as opportunities for parents to talk about smoking. As one parent stated, when his child sees someone smoking, “That’ll generally start a short discussion, even just a minute or two.” (CE) Most notable within this pattern of interaction, the child’s perspective was elicited and an important part of the discussion about smoking. “I’d probably ask him, ‘What do you think about that?’ ” (EH)

Discussions ranged from talking about health effects of smoking to talking about healthy lifestyle choices and decision making when confronted by peer pressure. Parents thought that children need to be “prepared ... before they’re in situations out on their own where they have to make some decision in front of their peers. I think that would be way too dangerous.” (EH) As another parent said, “If [we] could instill an antismoking or non-smoking behavior and lifestyle in our children I think ... they’d be more able to and have the better tools to resist peer pressure when they do hit [ages] 14, 15.” (FB) Parents began discussing smoking with their children when the children were pre-school age, “We started the dialogue very early, because they see it” (EH); raised thetopic often, “Every opportunity I get to educate them a little bit, I’ll do it” (CE); and added to the content and depth of the discussion as the children grew and were able to understand more about health.

We started the younger child ... to say it is really bad for your body and it hurts your body. ... But ... my oldest daughter’s age and my youngest daughter at this point [9 years old] ... it needs to be a little more specific about what smoking can actually do and, you know, the diseases that it can cause. ... At that age they almost need a little bit more information and they need a little bit more of a reason why they shouldn’t do it. (LA)

As another parent said, “Discuss it now in a way that is age appropriate for your child.” (EH)

Telling their children about smoking. About half of the parents had interactions with their children that reflected telling their children facts about smoking with a message indicating that they prohibited the behaviour. Parents sometimes raised the topic themselves but usually it came up as a result of the child making a comment or asking a question about smoking when prompted by something such as seeing someone smoke. The parents were didactic in their comments and responses and the child’s perspective was not elicited.

For some parents the topic of smoking had come up when the children were quite young, “as early as she [could] speak.” (HE). The facts the parents imparted to their children were mainly about health. However the strength and frequency of that messaging varied from “mentioning” it occasionally, such as when the child brought “something home [from school]” (HY) about smoking, to “hammering” it home often, “every chance I get” (JC). Similar to the group of parents who discussed smoking with their children, parents tended to provide different types and amounts of health information based on the child’s age and what they thought the child could understand. Parents were general in their messages when the children were young, telling them such things as smoking is “bad for health” (HE) or “dangerous to your health” (HY). They were more specific regarding illnesses and serious health effects when the children were older. A father illustrated his approach to age appropriate messagingFor the 4-four-year old, you have to just keep it simple and not give him too much information. If he asks a question I ... let him know it’s not good for you ... but the older kids they seem to always want more information. ‘How come it’s bad, not good for you? What does it do?’ Like that type. The 4-yearold seems to be satisfied with the simple answers. (ID)

Another parent noted, “The older she gets and the more she’s able to understand about it, I’m going to tell her. ... I tell her that people can get cancer because they smoke and they die.” (JC)

A few parents also told their children about peer pressure with added advice on how to deal with it. However, unlike the parents whose approach was to discuss smoking with their children and talked with their children about decision making concerning peer pressure, these parents were directive in their approach, simply telling the child what to do. Fostering decision-making was not part of their approach.

I told my son like if anybody ever tries to get you to smoke or tries to tell you that you’re not cool because you don’t smoke or calls you chicken or whatever, like don’t listen to them cause they’re the stupid ones. I often tell my son that. (AU)

Parents let their children know that they prohibited smoking by telling them they “expect them not to be smokers” (ID), telling them they “shouldn’t smoke”, or giving them a strong directive not to smoke such as “[don’t] even go there” (FG). Some parents added imperative, such as emphasizing the serious illnesses as a “scare tactic to try to keep him away from it” (SV) or using threats, “If I ever smell cigarette smoke on you, you wouldn’t want to ... have the consequences for that.” (EC) As one parent said, “If in any way I can convince her that it’s the wrong thing to do, I’m going to say it.” (JC)

Acknowledging their child’s understanding of smoking. A small group of parents acknowledged their children’s understanding of smoking by validating messages their children had received from sources such as school. These parents did not raise the topic on their own but responded when the child raised the topic by making a comment or asking a question about smoking. “Like, my kids have mentioned it when they’ve come home from school and stuff.” (AG) The parents’ responses tended to be brief. For example, a mother commented that when she told her son that his grandparents’ coughing was “because they’re smoking”. He replied, “ ‘I don’t want to cough like that’. So, I just tell him that’s good.” (BV)The parents did not elaborate on the message or pursue a discussion about smoking. “To actually sit down and talk about it, we’ve never done [that]. ... We don’t discuss it.” (GF) They simply went along with what the child knew. “[Child had] come home [from school] ... saying there’s chemicals in cigarettes. ... We basically [told] him he’s right.” (AG)

The younger school-age children had a simple understanding of smoking, such as smoking is “bad” for your health and “people get sick” (BV) from it. The children did not “mention” or “question” smoking often and the parents thought that what the children knew was enough for their age. As one parent said of her approach, she was “just touching base with [child] now because [child] is so young.” (MY) Another parent commentedWell I think with the younger age you ... have to make them understand smoking is bad for your health but ... I don’t think you should go so in depth that you’re scaring [them]. ... I know my son, it would freak him out and then he would have nightmares about it, that sort of thing. (GF)

The parents of older school-age children thought that smoking was covered well in school and therefore their children knew a lot about it. “She knows a lot of details about it. ... She’s basically repeating the things she’s ... heard at school about how bad it can be for your body.” (NW)

Not having talked to their children about smoking yet. Three parents had not talked to their children at all about smoking. Two of the parents were non-smokers and were the mother and father of a 7-year-old child. They had not given much thought to smoking yet because their child was young. One of them stated, “I have not raised the issue of smoking and it hasn’t even occurred to me yet at this time yet with her age.” (DD) Further, their child was never exposed to smoking in the family or through family friends, did not seem to “notice” smoking in the environment, and had never “mentioned” smoking to them. The third parent indicated that her child, who also was 7-years-old, had learned about smoking in school but had “never questioned it” or “asked [the parent] directly about it” (TX) and seemed to not pay much attention to smoking. Although she smoked, she had “never smoked around” her child and thought he did not know she smoked. In essence, the parents in this group had not perceived a need to address smoking with their children up to that point and were not prompted by their children to do so. Although they had not talked to their children yet about smoking, they indicated that they would in the future. “I’d definitely want to discuss it with her and any concerns that she had about it and I’d try to educate her on the negative implications and impacts from it.”(BF).

Parental disapproval of smoking. The parents’ disapproval of smoking took the form of displaying a negative attitude toward smoking, admonishing their children for mimicking smoking, and leading by example, which involved being a non-smoker and for some parents also having a non-smoking home. The first two behaviours may be considered active approaches as the parents verbally communicated their thoughts to their children. Leading by example may be considered a more passive approach as the disapproval was implied by the behavior, rather than by direct verbal communication of it to their children. The parents’ disapproval of smoking may be categorized by whether or not they had verbally interacted with their children about smoking.

Parents who had verbally interacted with their children about smoking. Many parents who had verbally interacted with their children, through either of discussing smoking with their children, telling their children about smoking, or acknowledging their children’s understanding of smoking, including parents who smoked, also had exhibited one or both of displaying a negative attitude toward smoking and admonishing their children for mimicking the behaviour. Non-smoking parents suggested they were leading by example. For a few parents leading by example appeared to be their only expression of disapproval.

Displaying a negative attitude toward smoking. Parents displayed a negative attitude by making negative comments in their children’s presence about smoking, such as smoking is “gross” or “stupid”, when the topic came up or when smoking caught their attention. One parent related how she responded to her child who smelled of cigarette smoke when he came home from playing at a friend’s house in which the parents were smokers. “ ‘I just really need you to go have a shower right now because I can smell this on you.’ ... just to let him know that I don’t like even the smell, kind of thing.” (CX) By displaying a negative attitude, the parents were letting their children know “how [they] feel about smoking.” (AU)

Admonishing their children for mimicking smoking. Interestingly, a large number of parents, both smoking and non-smoking parents, had seen their children mimic smoking. The children used objects such as a candy stick, pencil, or crayon to pretend to be smoking. A few non-smoking parents did not consider the mimicking to be of consequence or considered that it was “just play” and therefore did not pay attention to it. However, many parents were disturbed by the behaviour and admonished their children for doing it by letting them know that they did not like what the children were doing and they should not pretend to smoke because smoking for real is harmful and “it’s not good to even pretend”. (RU) “I scolded them for pretending to smoke and told them not to do that. Smoking is not fun. They shouldn’t joke around about it.” (ID) Although they did not want their children engaging in such behaviour, parents were not surprised by it as they thought it is only natural for children to mimic a behaviour to which they are commonly exposed, if not by family members then within the environment more generally. A mother who smoked was “horrified” when she saw her child pretending to smoke as she knew “it’s a learned behaviour. It’s what they see. Children do what they see.” (NW) Another mother conveyedI used to smoke in front of [daughter] and about three years ago she started trying to smoke crayons. ... [I said] ‘What are you doing (daughter)?’ She said, ‘I’m smoking this. I’m smoking like you smokes, Mommy.’ And, I said, ‘No, no, no, no, you can’t be smoking. It’s not good for you’. ... ‘But you do, Mommy.’ (HY)

After that the mother no longer smoked in the daughter’s presence.

Leading by example. The parents knew that children emulate their parents: “Monkey see, monkey do.” (SV) For that reason, parents who currently were non-smokers believed they were leading by example. For some parents having a non-smoking home was another reason for that belief. Parents thought that antismoking messages are more effective when they come from parents who “practice what [they] preach.... So, they see that we don’t smoke and there’s no smoking in our house and our friends don’t smoke.” (FB)

If you are a smoker yourself, and I do have friends who are smokers and family members ... who are smokers and then they are telling their children smoking is bad for you and kind of going out by the door to do it. ... They are leaving the room, but the kids still know mom’s gone for a smoke. ... I think if you are telling your kids not to smoke, it’s kind of hypocritical if you’re smoking yourself. ... The best way ... parents can be a good example, to raise non-smokers, is to be non-smokers themselves. (RU)

Parents who had not yet talked with their children about smoking. Similar to other non-smoking parents in this study, the two non-smoking parents in this group, although not having interacted with their children about smoking, indicated they were leading by example. “Well, hopefully with them having non-smokers for parents, like I’m hoping that’s going to be a good influence for them.” (BF)

3.3. Role of Society

Parents thought that generally there was an increased awareness in society of the ill effects of smoking compared to when they were growing up and as a consequence smoking had become less acceptable and less prevalent. “When my husband started to smoke, the knowledge wasn’t out there. ... But say now, I don’t think it’s nearly as acceptable to start because we know so much more.” (DZ) However, they recognized that smoking among youth still is a significant problem and thought more should be done at the societal level to further impact it. “I don’t think there is enough emphasis on the smoking piece. I really don’t. I don’t think there is enough emphasis publicly.” (HY) Their view was that in addition to sending a strong antismoking message through regulations and policies to prevent exposure of children to smoking and tobacco products, society has a role to play through providing public education. In particular, parents thought there was little in the way of educational resources directed to parents about youth smoking as they “hadn’t come across anything for parents.” (EH) “There’s not a lot out there that you can hold on to and run with.” (NW)

Several parents, irrespective of the approach they were taking with their children about smoking and regardless of their smoking status, were uncertain about the appropriateness of their approach. They thought they could benefit from resources about prevention measures and how to go about intervening with their children about smoking, such as what to say to their children at different ages.

I would want some more education I guess on how to talk to my child about it and like I do say what is on my mind about it and how dirty and ugly and gross it is, but ... should I talk about death and dying with her about smoking, you know, at age 7 ... What age should I begin. (KB)

Other parents were comfortable with their approach but thought that generally it would be helpful to parents to have educational resources to guide their approach with their children. Parents also thought there were few if any age-specific smoking prevention resources and messages for young and pre-adolescent children. Resources such as videos, booklets, and television commercials could be helpful to parents to “open up the topic for further discussion.” (DD)

3.4. Role of School

Although society has a role to play in smoking prevention education for children, parents placed even greater emphasis on the importance of schools. Many parents thought that smoking prevention education was being carried out in the elementary grades as their children had told them things they had learned in school about smoking or had brought educational materials about it home from school. Some of those parents thought that the smoking prevention education was delivered regularly in various elementary grades as a component of the school curricula. Others did not know whether smoking prevention education was part of the formal curricula for elementary grades but thought that it was offered more “randomly” and “periodically”. Some parents did not know at all whether smoking was addressed in their children’s school. Their children had not mentioned anything from school about smoking and had not brought anything home about smoking.

Whether or not education about smoking already was being carried out in schools at the elementary level, parents thought it ought to be. “School has a pivotal role to play in setting those [antismoking] attitudes.” [CE] In addition to preparing children before they are exposed to increased risk for smoking in the later grades, some parents thought that smoking prevention education at school could assist parents in their efforts to deter the behavior. As with other forms of public education for children about smoking, information presented in school and related material sent home could “open up ... the door to discuss” (HY) the behavior at home and “reinforce” the message. As one parent commented, “When it’s covered in school and they have like a little bit of background with it, [and] they kind a come home asking questions and with information and stuff, I find that always a good opportunity for discussion... . It ... kind of puts it in your mind.” (LA)

3.5. Hoping Their Children Would Not Smoke

Regardless of the extent of their own communication with their children about smoking, parents who had verbally interacted with their children on the topic thought their children understood the health message about smoking. Whether through the parents, school, society generally, or a combination of sources, the children had knowledge of the health effects of smoking and demonstrated an antismoking attitude. Most of the children had specifically declared that they “would never smoke”. (LA) Some children had confronted their parents or relatives about the health issues. A mother who smoked commentedShe’ll say, ‘Mom, do you know smoking is bad for you? Smoking ruins every part of your body. Smoking affects your lungs.’ ... So, she’s telling me things I already know deep down. ... She’s very persistent about it. ... She doesn’t say it every day but she does say it a lot.” (NW)

Although the parents knew it was possible for their children to begin smoking, they were “hoping” that they would not, and their children’s understanding of smoking gave them encouragement. “It is the last thing I ever want to see him do is smoke.” (FG) “I know she knows the downsides of it so I would hope that she would ... say ‘No, I’m not going to do it.’ ” (NW)

The parents who had not yet talked with their children about smoking also were hoping that their children would not smoke. They were hoping that when their children are old enough to be in a situation where they might contemplate smoking that they will be “educated” enough to make the decision to be “smoke-free”. As one parent said, “Like any parent you don’t want to see your kids do it and you just ... [hope] ... they get messages through school or through you or through someone else.” (TX)

4. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study are consistent with findings of other studies in which many parents reported addressing the topic of smoking with their school-age and pre-adolescent children [20] or pre-adolescent children [22] to at least some extent and other parents reported not addressing the topic at all with their children. Further, the various verbal interaction approaches the rural parents in this study had taken with their children concerning the topic of smoking are consistent with the approaches urban parents in another study had taken with their school-age pre-adolescent children [20].

Although parenting styles, the different approaches by which parents interact with and respond to their children generally in terms of limit-setting and nurturance [23,24], were not examined in this study, how the parents communicated with their children about smoking may be likened to the communication patterns inherent in parenting styles. Some of the parents had discussed smoking with their children using an open engaging style; others had told their children about smoking using a directive style; and still others had merely acknowledged to their children the children’s understanding of smoking and they were nondirective and unengaged in their style. These communication styles resemble the communication patterns of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting styles, respectively, as proposed by Baumrind [24,25]. Authoritative parenting is predicted to result in better psychosocial and behavioural outcomes than the other two styles [24].

No studies were found regarding the effectiveness for smoking prevention of smoking-specific communication with pre-adolescent children. However, previous research with adolescents has shown that good quality smoking-specific parental communication, demonstrated by a constructive and respectful manner, was a deterrent to smoking initiation among the adolescents [17,26]. Further, the overall approach of the parents in this study who discussed smoking with their children is consistent with recommendations and suggestions of authorities and experts in the field of youth smoking prevention [16,18, 27-29].

Parents who had verbally interacted with their children about smoking also had showed disapproval of smoking through one or more of displaying a negative attitude toward smoking, admonishing their children for mimicking smoking, and leading by example, which involved being non-smokers and for some parents also having non-smoking homes. No studies were found in which parental attitude toward smoking was examined in relation to antismoking measures with school-age and preadolescent children. However, there is some evidence that parental antismoking attitude is protective for initiation of smoking in adolescence, such that adolescents are less likely to begin to smoke when their parents hold strong antismoking attitudes [30,31].

Although many of the parents in this study admonished their children for mimicking smoking, a few non-smoking parents had not intervened to show their disapproval of it as they did not think the play behaviour was significant. That children engage in such behaviour during play has been demonstrated in other studies and has been found to be positively associated with parental smoking; but as was the case in this study, children of non-smokers also engaged in the behaviour [32,33]. Likewise, although parental smoking [34,35] and permitting smoking in their home [36-38] are associated with increased risk of youth smoking, some children may smoke despite having non-smoking parents [39,40] and smoke-free homes [39].

Even though some children may smoke regardless of parental antismoking behaviour, parental disapproval of smoking in forms such as used by parents in this study are considered important antismoking socialization practices [41,42]. Indeed, several socio-psychological theories such as the Theory of Planned Behavior [43], Social Cognitive Theory [44], and Problem Behavior Theory [45] provide support for parental antismoking socialization through premises regarding parental disapproval of the problem behaviour and parental role modeling of the desired behavior [46]. However, children might not know that their parents are against smoking if the parental disapproval is not brought to their awareness and as suggested in other research might assume that smoking is not an important issue for the parents if clear disapproval is not conveyed [47]. Further, as reported by some of the parents in this study, some children might not be attentive to smoking. Therefore, they might not recognize the fact that their parents are non-smokers or their homes are non-smoking if their parents do not explicitly draw their attention to and address with them the significance of the parent’s non-smoking status and their smoke-free home. This particularly may be the case in situations where parents do not talk about smoking with their children or do so only minimally. Indeed, there were parents in this study who thought they were leading by example because they did not smoke, but they had not discussed smoking with their child or had communicated only minimally through acknowledging their children’s understanding of smoking.

To ensure their children know their stand on smoking, then, parents need to take an active approach to antismoking socialization of their children. In addition to proactive, good quality discussions with their children that are inclusive of the topic, it is suggested by authorities in the field that parents talk with their children about their disapproval of the behaviour. Further, because of the potential for emulation of parental smoking, it is essential for parents who smoke to (a) talk with their children about why they started to smoke and about the power of their addiction; (b) let their children know that smoking is unacceptable and they do not want to smoke, are aware it is bad for their health, and would like to quit; and (c) avoid smoking in their children’s presence and tell their children why that is the case [16,18]. It is argued that parents who smoke still can have an influence against the behaviour [18,28]. In this study, regardless of the verbal interaction approach the smoking parents had taken with their children and regardless of whether they were hiding their smoking, most of them had explicitly expressed to their children their disapproval of smoking. Parents who hide their smoking from their children need to be prepared to address with their children their contradictory behaviour should their children discover their smoking.

Implications for Practice and Further Research

The parents in this study had knowledge of the health effects of smoking and youth smoking, thought that education is the key to protecting children against smoking, and thought that parents have an important role to play in that education. Many parents engaged in efforts to deter their children from the behaviour; although, some were uncertain as to whether their approaches were appropriate. In general, parents thought that there was a lack of educational resources for parents about youth smoking and a lack of age-appropriate smoking prevention resources or messages for young and pre-adolescent children but that such resources would be helpful to informing or guiding parents’ smoking prevention interventions with their children.

Public health and school nurses who interact with parents, therefore, are encouraged to (a) take advantage of parents’ understanding of smoking and of parents’ recognition of their own role in smoking prevention to emphasize the importance of early parental antismoking intervention with their children and the potential positive influence that parents can have on deterring their children from smoking, (b) support parents whose communication with their children about smoking is consistent with recommendations in the literature, (c) offer guidance and support to parents whose communication is inconsistent with recommendations, and (d) advocate for and make available educational resources to facilitate parents’ communication with their children about smoking. Although the parents in this study knew that it was possible for their children to begin smoking and that adolescents are especially at risk, they were hoping that their children would not smoke. Many were encouraged by their children’s understanding of smoking and antismoking attitude. Nurses are encouraged to discuss with parents the importance of continuing to talk with their children throughout childhood and adolescence about smoking as children may change their negative view of smoking to acceptance of it as they get older, especially as they transition into junior high or high school [18].

In addition to parents’ role in smoking prevention education, parents in this study thought that society and schools also have important roles to play. This is consistent with the perspective that a comprehensive, multichannel approach is required to achieve the greatest effect for smoking prevention [3,16]. Although parents thought that smoking prevention education needs to be carried out at the elementary level in school, some parents did not know whether smoking was addressed at their children’s schools. Nurses are encouraged to talk with parents about how to contribute to smoking prevention education in schools. Parents can become involved by talking with their children about what the children are learning in school about smoking and reinforcing and complementing the messages and by advocating for strong prevention curricula. Parents need to take a proactive role in communicating with their children about smoking regardless of whether education is provided at the school and societal levels.

Findings from this study are consistent with findings from previous studies and contribute to what was known about parental communication with children about smoking. However, the study consisted of a small sample of parents who were self-selected for participation in the study, the majority of whom were from middle and higher income brackets and had at least some post-secondary education. Further, there were few fathers and few smoking parents. Thus, other research should be conducted to confirm the communication patterns revealed in this study, determine whether other patterns exist, and determine whether and what sociodemographic factors influence parents’ smoking-specific communication with their children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded through a research grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals/Canadian Lung Association.

FUNDING

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to the study and manuscript.

REFERENCES

[1] World Health Organization (2011) WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2011: Warning about the Dangers of Tobacco. Geneva. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789240687813_eng.pdf

[2] US Department of Health and Human Services (2004) The health consequences of smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2004/complete_report/index.htm

[3] US Department of Health and Human Services (2012) Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2004/complete_report/index.htm

[4] Di Franza, J.R., Savageau, J.A., Rigotti, N.A., Fletcher, K., Octene, J.K., McNeill, A.D., Coleman, M. and Wood, C. (2002) Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tobacco Control, 11, 228-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.11.3.228

[5] Di Franza, J.R., Savageau, J.A., Fletcher, K., O’Loughlin J., Pbert, L., Ockene, J.K., McNeill, A.D., Hazelton, J., Freidman, K., Dussault, G., Wood, C. and Wellman, R.J. (2007) Symptoms of tobacco dependence after brief intermittent use: The development and assessment of nicotine dependence in youth-2 study. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 161, 704-710. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.7.704

[6] US Department of Health and Human Services (2010) How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/tobaccosmoke/full_report.pdf

[7] Health Canada (2012) Summary of results of the 2010- 2011 youth smoking survey. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/_survey-sondage_2010-2011/result-eng.php

[8] The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University (2007) Tobacco: The smoking gun. Prepared for the Citizen’s Commission to Protect the Truth. A CASA white paper. http://www.casacolumbia.org/articlefiles/380-Tobacco-The%20Smoking%20Gun.pdf

[9] Health Canada (2012) Canadian tobacco use monitoring survey (CTUMS): Summary of annual results for 2011. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/_ctums-esutc_2011/ann_summary-sommaire-eng.php

[10] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Current tobacco use among middle and high school studentsUnited States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61, 581-585.

[11] Canadian Institute for Health Information (2006) How healthy are rural Canadians? An assessment of their health status and health determinants. Author, Ottawa. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/rural06/pdf/rural_canadians_2006_report_e.pdf

[12] Des Meules, M., Pong, R.W., Guernsey, J.R., Wang, F., Lou, W. and Dressler, M.P. (2012) Rural health status and determinants in Canada. In: Kulig J.C. and Williams, A.M., Eds., Health in Rural Canada, UBC Press, Vancouver, 23-43.

[13] Health Canada (2009) Health concerns: Canadian tobacco use monitoring survey (CTUMS) 2008—Summary of annual results for 2008. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/ctums-esutc_2008-eng.php

[14] American Lung Association (2012) Cutting tobacco’s rural roots: Tobacco use in rural communities. American Lung Association, Washington DC. http://www.lung.org/assets/documents/publications/lung-disease-data/cutting-tobaccos-rural-roots.pdf

[15] Lutfiyya, M.N., Shah, K.K., Johnson, M., Bales, R.W., Cha, I., McGrath, C., Serpa, L. and Lipsky, M.S. (2008) Adolescent daily cigarette smoking: Is rural residency a risk factor? Rural and Remote Health, 8, 1-12.

[16] American Academy of Pediatrics (2009) Policy statementtobacco use: A pediatric disease. Pediatrics, 124, 1474- 1487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2114

[17] de Leeuw, R., Scholte, R., Vermulst, A. and Engels, R. (2010) The relation between smoking-specific parenting and smoking trajectories of adolescents: How are changes in parenting related to changes in smoking? Psychology and Health, 25, 999-1021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870440903477204

[18] Health Canada (2008) Help your child stay smoke-free: A guide to protecting your child against tobacco use. Minister of Health, Ottawa.

[19] Kulbok, P.A., Bovbjerg, V., Meszaros, P.S., Botchway, N., Hinton, I., Anderson, N.L.R., Rhee, H., Bond, D.C., Noonan, D. and Hartman, K. (2010) Mother-daughter communication: A protective factor for non-smoking among rural adolescents. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 21, 69-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10884601003777604

[20] Small, S.P., Eastlick Kushner, K. and Neufeld, A. (2012) Dealing with a latent danger: Parents communicating with their children about smoking. Nursing Research and Practice, 2012, Article ID 382075. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/382075

[21] Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1998) Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd Edition, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

[22] Beatty, S.E., Cross, D.S. and Shaw, T.M. (2008) The impact of a parent-directed intervention on parent-child communication about tobacco and alcohol. Drug and Alcohol Review, 27, 591-601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09595230801935698

[23] Baumrind, D. (1968) Authoritarian vs. authoritative parental control. Adolescence, 3, 255-272.

[24] Baumrind, D. (1991) The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence, 11, 56-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431691111004

[25] Baumrind, D. (1993) The average expectable environment is not good enough: A response to Scarr. Child Development, 64, 1299-1317. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1131536

[26] den ExterBlokland, E.A.W., Engels, R.C., Harakeh, Z., Halle III, W.W. and Meeus, W. (2009) If parents establish a no-smoking agreement with their offspring, does this prevent adolescents from smoking? Findings from three Dutch studies. Health Education & Behaviour, 36, 759-776. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1090198108330000

[27] Small, S.P., Eastlick Kushner, K. and Neufeld, A. (2013) Smoking prevention among youth: A multipronged approach involving parents, schools and society. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 45, 116-135.

[28] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Smoking and tobacco use: What parents should know—Parents help keep your kids tobacco-free. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/youth/information_sheet/

[29] US Department of Health and Human Services (2010) Smoking and how to quit: For parents—What parents can do. http://womenshealth.gov/smoking-how-to-quit/for-parents/

[30] Andersen, M.R., Leroux, B.G., Marek, P.M., Petersen, A.V., Kealwy, K.A., Bricker, J. and Sarason, I.G. (2002) Mothers’ attitudes and concerns about their children smoking: Do they influence kids? Preventive Medicine, 34, 198-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2001.0971

[31] Andrews, J.A., Hops, H., Ary, D., Tildesley, E. and Harris, J. (1993) Parental influence on early adolescent substance use: Specific and nonspecific effects. Journal of Early Adolescence, 13, 285-310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431693013003004

[32] de Leeuw, R.N., Engels, R.C. and Scholte, R.H. (2010) Parental smoking and pretend smoking in young children. Tobacco Control, 19, 201-205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2009.033407

[33] de Leeuw, R.N.D., Verhagen, M., de Wit, C., Scholte, R.H.J. and Engels, R.C.M.E. (2011) “One cigarette for you and one for me”: Children of smoking and nonsmoking parents during pretend play. Tobacco Control, 20, 344-348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2010.039909

[34] Leonardi-Bee, J., Jere, M.L. and Britton, J. (2011) Exposure to parental and sibling smoking and the risk of smoking uptake in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax, 66, 847-855. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.153379

[35] Vuolo, M. and Staff, J. (2013) Parent and child cigarette use: A longitudinal, multigenerational study. Pediatrics, 132, e568-e577. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0067

[36] Clark, P.I., Schooley, M.W., Pierce, B., Schulman, J., Hartman, A.M. and Schmitt, C.L. (2006) Impact of home smoking rules on smoking patterns among adolescents and young adults. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/apr/05_0028.htm

[37] Muilenburg, J.L. and Legge, J.S. (2009) Investigating adolescents’ sources of information concerning tobacco and the resulting impact on attitudes toward public policy. Journal of Cancer Education, 24, 148-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08858190902854798

[38] Rainio, S.U. and Rimpela, A.H. (2007) Home smoking bans in Finland and the association with child smoking. European Journal of Public Health, 18, 306-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckm098

[39] Berg, C., Choi, W.S., Kaur, H., Nollen, N. and Ahluwalia, J.S. (2009) The roles of parenting, church attendance, and depression in adolescent smoking. Journal of Community Health, 34, 56-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9118-4

[40] Peterson, A.V., Leroux, B.G., Bricker, J., Kealey, K.A., Marek, P.M., Sarason, I.G. and Anderson, M.R. (2006) Nine-year prediction of adolescent smoking by number of smoking parents. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 788-801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.06.003

[41] Jackson, C. and Dickinson, D. (2003) Can parents who smoke socialize their children against smoking? Results from the Smoke-Free Kids intervention trial. Tobacco Control, 12, 52-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.1.52

[42] Johnson, P.B. and Johnson, H.L. (2001) Reaffirming the power of parental influence on adolescent smoking and drinking decisions. Adolescent and Family Health, 2, 37- 43.

[43] Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

[44] Bandura, A. (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

[45] Jessor, R. (1987) Problem-behavior theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. British Journal of Addiction, 82, 331-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01490.x

[46] Petraitis, J., Flay, B.R. and Miller, T.Q. (1995) Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 67-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67

[47] Crawford, M.A. and The Tobacco Control Network Writing Group (2001) Cigarette smoking and adolescents: Messages they see and hear. Public Health Reports, 116, 203-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/phr/116.S1.203