Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.2 No.3(2012), Article ID:23142,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.23029

The healthcare environment—The importance of aesthetic surroundings: Health professionals’ experiences from a surgical ward in Finland

![]()

1Department of Health, Nutrition and Management, Faculty of Health Sciences, Norway Karolinska Institute, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden

2Department of Photography, Novia University of Applied Sciences, Wasa, Finland

3Manager of Research and Development, Novia University of Applied Sciences, Wasa, Finland

Email: britt-maj@home.se, Emma.westerlund@novia.fi, Jaana.erkilla@novia.fi

Received 22 May 2012; revised 22 June 2012; accepted 5 July 2012

Keywords: Hospital Ward Environment; Enrichment; Health Professionals

ABSTRACT

There is a growing acceptance of the vital role patient centered design plays in shaping the environment. Art can be of use in every area of health care. It is within the power of each person to share and interpret experience by means of the arts, by viewing the work of others, and by using feelings and imagination. Health professionals [n = 24 of a total of n = 35], answered the Wheel Questionnaire test instrument. It measures structure, motivation/engagement, and degree of emotional investment in a situation. Participants were requested to describe, in their own words, their perception of the enrichment of the ward interiordesign and the double-sided photos with a short poetic text, and the photo-book placed at each patient room. The results demonstrate that participants are motivated, structured and emotionally engaged when describing the new enrichment. The domains and themes are: Social interaction domain; rising thoughts and conversations. Comfort domain; atmosphere. Aesthetic do main; enrichment of the working environment. It could be concluded that the surgical ward environmental enrichment stimulated conversations between health professionals and between health professionals and patients and should be regarded as an important aspect in hospital planning.

1. INTRODUCTION

Institutions are sometimes perceived as commanding. It is an indisputable fact that some of our older hospitals, and some built more recently are uninviting places. Important experiences in life take place in hospitals; nevertheless they can be most uninspiring and depressing environments. Very often, because of the need for clinical areas, the rest of the hospital suffers from institutional atmosphere. The environment has an impact on our lives and there is a growing acceptance of the vital role patient centered design plays in shaping the environment. The physical environment is always present and can affect the body both physiologically and psychologically by what we take in and interpret through our senses. A caring environment intends to promote acts of caring. It is the nurse’s responsibility to develop a nourishing healthcare environment and consider the aesthetic aspects of the healthcare environment [1]. Art should be incorporated into the environment. Art can be of use in every area of health care. It is within the power of each person to share and interpret experience by means of the arts, by viewing the work of others, and by using feelings and imagination and increasing the understanding of what the world has to offer. Today research shows that visual art could be used in order to stimulate conversations with patients, infuse new subjects to discuss, and reach contact with patients [2,3]. Cintra [4] has made possible the inclusion of public art in eight hospitals. She concluded that good art in health care settings engage the users in a dialogue.

The present study was conducted at a surgical ward at a hospital in Finland. The intention is to present and discuss the results from reshape and environmental enrichment of this surgical ward; the use of colors, textiles, new furniture and photos. The study aimed at describing health professionals’ evaluation and wishes of the enriched ward interior design; its value and its possibilities for the patients and relatives, and personnel working at the ward. An underlying assumption was that the field of aesthetics is a neglected area in many hospital environments. Supportive design promotes stress reduction, a documented problem for patients, families and visitors as well as healthcare employees [5-7]. However, there is still a belief that art is a luxury.

1.1. Research Question

What effects could a reshape and environmental enrichment of a surgical ward have for health professionals regarding positive and/or negative perception of their working environment?

1.2. Literature Review—The Implication of Art Health Care Environment

There is a growing awareness internationally of the need to create functionally efficient and human centered healthcare environments. We have to take a step towards aesthetic health care environments in order to meet the new requirements. Still, some hospitals in use in Scandinavia do not satisfy the needs for patients, their relatives and health professionals. The health care environment such as design, colors, art and sound are important to consider when planning for patients, healthcare providers and relatives. Patients are those who are most influenced of the healthcare environment. An aesthetic and supportive healthcare environment enhances people’s capability to better cope with stress. The perception of the healthcare environment is described from a patient-centered perspective. Patients express that the healthcare environment is important for interaction improvements between relatives and healthcare providers [8-10]. The effects and meaning of aesthetic surroundings for perceiveing energy and well-being should always be in focus [11]. Art in healthcare environments reduces anxiety and depression. The effects of ward design have a positive influence on the well-being of post-operative patients [12, 13]. Almost positive effect from the patients’ perspective regardingvisual and performing arts in healthcare has been reported [14].

Several studies reported that the architectural healthcare environment was important for positive effects on patient health outcomes. The studies reported better health outcomes by design focusing on understanding the healing environment [6,7,15,16]. Wellness factors in health care environment are a vital ground pillar in the therapeutic process. Patients react constructively if he or she has good experience of healthcare environments. They find enhanced ways to resolve problems. Inappropriately designed healthcare environments on the other hand, may be a source of stress and frustration [1]. Health care design is a vital part in the healing process in order to promote positive health outcomes [17,18].

1.3. The Meaning of Aesthetics

The meaning of aesthetics has been formulated by ancient philosophers who saw a natural link between art and life. Painting, drama, dance and music were obvious parts of everyday life, and they were regarded as a cure of body and mind. Physical and psychological health as it has been described by philosophers like Aristotle [19], is to be found in the research of today [20-27]. Aesthetic forms of expression for elderly individuals can mean discovering, preserving, or developing possibilities for a meaningful life. Controlled intervention studies report that paintings bring forth beneficial effects in elderly individuals [2,3]. Dialogues generated by reproductions of works of well-known artists had a positive impact on elderly individuals’ perceptions of their life situation and social interaction compared to a control group in which dialogues were about events of the day and the elderly individuals’ hobbies and interests [28]. In a survey of living conditions 12,675 people were interviewed and then conducted follow up with respect to survival. The results show that attendance at cultural events, which included visiting museums, art exhibitions, theaters or concerts, reading books, and singing in a choir, had a positive influence on survival rates [29].

2. METHOD

2.1. Descriptions of Measures and Data Analysis

The foundation for data collection is based on a modelthe Sequential Appraisal Model (SAM) [30-32]. This model can be viewed as an extension of a model of appraisal. The perception is based on a three level process (appraisal, mobilization, realization).

The Wheel Questionnaire (WQ) assesses the first stage of the perceptual process, i.e. cognitive appraisal or the quality of structure and lack of ambiguity in the perceived situation; the affective appraisal or the degree and valence of emotional involvement in the situation; the instrumental appraisal or the feeling of the ability to control and affect the situation.

The Wheel Questionnaire test instrument is an appraisal of an imagined, expected or experienced situation. The appraisal process was based on participants’ experiences and expectations. Different individuals will perceive a similar situation in different ways. For example, the same situation may be perceived as positive, negative or neutral.

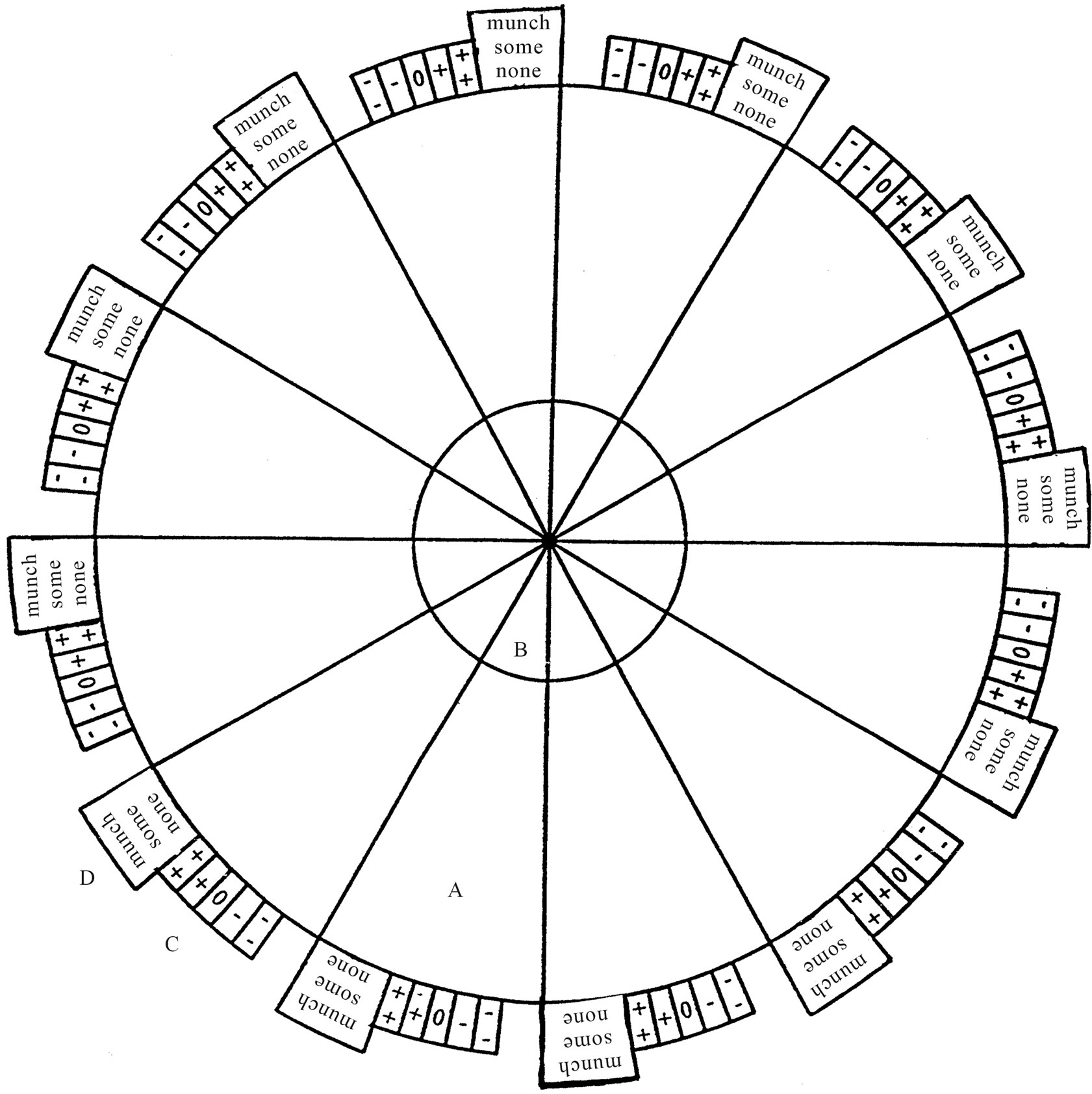

In the first step, participants were asked to write down, in their own words, opinions on the reshaped surgical ward they worked at in the wheel-shaped questionnaire [Figure 1(A)]. They could write one opinion or more (maximum of 12) in each of the wheel’s segments. Next they were asked to rank these opinions in order of importance, the most important as 1 the second most important as 2, and so forth. The same rank could be given to two or more factors [Figure 1(B)]. Then they had to

Figure 1. The wheel questionnaire test instrument.

evaluate which opinion they consider to be positive or negative. These assessments were marked on a 5-point scale [Figure 1(C)]. Lastly, participants were asked to assess how much control/influence they felt they have. This is entered on a 3-point scale (much, some, none) [Figure 1(D)]. If any participants had questions about the questionnaire, these were answered by the project leader.

The WQ-test instrument is designed to map structure, motivation/engagement, and degree of emotional investment, indicating engagement in a situation as shown in the following equations:

Structure: R

This index is based on the maximum number of ranks given over the total number of factors (thoughts and opinions).

Structure: R = r’ − 1/d The index ranks between: 0.00 - 0.92. Thus the higher the R value the less ambiguous and more differentiated is the appraisal of the situation mapped by the WQ.

Motivation: M

The index is based on the absolute sum of positive and negative responses (L).

Ranks between: 0 - 24 (high ranking points at high motivation and engagement, low ranking points at low motivation and engagement).

Emotional investment: E ≤ L/d

The direction of the emotional involvement, the sum of positive and the negative evaluations, i.e. is the final picture perceived as attractive, harmful or gentle. Thus the intensity of the direction of involvement is shown by the net to valence value associated with the extent of perception. This index is calculated by algebraically summing up the total number of positive and negative evaluations and standardizing them by dividing them by the number of factors given. The range of possible responses is from −2 to +2 (−24/12, 24/12).

With the WQ-test instrument, participants were requested to describe, in their own words, their perception of the enrichment of the ward interior design. They were also asked to reflect over the significance of the double-sided photos that had a short poetic text, and the photo-book placed at each patient room.

Health professionals at the ward [n = 24 of a total of n = 35], answered the WQ-test instrument [women n = 18, men n = 6]. Mean age women 40 [Range 25 - 58], mean age men 44 [Range 35 - 53].

2.2. Degree of Complexity in the Photos

Photos were chosen on the basis of reactions to and perceptions of pictures as described in the history of art [33-37]. It will be based on the premise that pattern are judged to be interesting if they contain information that could not be absorbed immediately, but seemed likely to be absorbed relatively quickly, both perceptually and intellectually. It will be important that the level of uncertainty, which includes complexity, ambiguity and variability are neither too high nor too low, i.e. in balance with the viewer’s ability to perceive it [34]. An important aspect reported complementary to Berlyne’s research [38-41]. The degree of realism, the lack of sharply outlined forms and the angular structure will vary. In addition the quality of the subject matter, active/passive color effects and the degree of dramatic action will vary as well. Photos are not always peaceful and tolerant in attitude. On the contrary, some photos are expressly designed to convey emotions of hatred and prejudice. Therefore the selection of photos must be made with care, in collaboration with the onlooker.

The balance between complexity and level of representativeness in the photos was considered important in the method, not too high or too low. This is earlier described by Berlyne [34] and in later research [42].

2.3. Data Analysis

The opinions were analysed according to qualitative research [43]. Reading the text carefully to gain an overview. Re-reading the text and searching the data for concepts relevant to experiences of the reshaped and environmental enrichment of the surgical ward of important to health professionals. The next step is to search the descriptive codes, and finally developing themes from the codes. Rigor was achieved when a clear decision trail was followed. This meant that any reader or another researcher could follow the progression of events in the study and understand the logic and justification for what was done and why [44].

Validity was assured by quoting directly from the text and the connection of the interpretation to previous research in the area. The literature was referenced in appropriate places [45].

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The researchers decided not to interview the patients out of consideration for their integrity due to their defenselessness. The project was approved by the Regional Committee. Data collection followed the Helsinki decalration [46]. Qualities that are judged are ethical perspectives, the research design and the need in society for such a project. The purpose and procedure of the study were explained carefully to the participants, and they were ensured of confidentiality.

3. RESULTS

3.1. WQ-Test Instrument—Motivation, Structure, Emotional Investment

With the WQ-test instrument, participants were requested to describe, in their own words, their perception of the enrichment of the ward interior design. They were also asked to reflect over the significance of the double-sided photos that had a short poetic text, and the photo-book placed at each patient room. This photo-book had, like the photos, a short reflection, a few lines, that mirror the representation of the photo. The aim of this text was to help the onlookers to start a conversation.

It was clear from the results of the analyses of the WQ-test instrument that the new art interior design was associated with a positive perception by the participants. They were motivated, structured and emotionally engaged when describing the new enrichment of the surgical ward. Emotional investment in their engagement was (1.34) on a scale range from (0 - 2). Participants were structured when they describe the meaning of aesthetic enrichment of the surgical ward; (0.5) on a scale range from (0 - 0.9). Finally the WQ-test instrument showed that the participants were motivated (9) on a scale range from (0 - 24).

3.2. Domains and Themes Generated from the WQ-Test Segments

The physical design of the healthcare environment generated three different domains: social interaction, comfort and aesthetics.

Social interaction domain

Theme: Arising thoughts and conversations

• Positive for patients ... and myself ... to talk about

• The text added to the photos … stimulating ... dialogue

• The book ... it helped to get close to ... the painting

• ... it helps to start a conversation ...

• ... the photos create curiosity ... representation of the photo ... conversation

Comfort domain

Theme: Atmosphere

• ... less sterile environment ...

• Calming ...less stress ...

• Relaxed ... comfortable ... environment

• It makes the environment ... caring ...

• ... you could touch the photo ... it’s ... a nice feeling ... you become happy... easier to work ...

• ... design has the capacity to reduce stress ...

Aesthetic domain

Theme: Enrichment of the working environment

• ... the décor ... great

• It is a boring environment ... without art

• ... colours contribute to well-coming ward

4. DISCUSSION

The present study could be said to originate from ancient Greece. The meaning of aesthetics has been formulated by ancient philosophers who saw a natural link between art and life, a part of everyday life, as a cure of body and mind [19]. In research of today this is to be found as well [22-25].

The present study supported the view that aesthetic environmental enrichment of a surgical ward, including colour, textile and photos, was perceived as positive by health professionals. Related to their experiences and expectations the environmental enrichment promoted a perceived positive atmosphere and an enrichment of their work circumstances. It was expressed in the comfort domain with the theme atmosphere in excerpts such as “... less sterile environment”, “calming ... less stress”, “relaxed ... comfortable ... environment design has the capacity to reduce stress”. Similar findings were found in research by Lassenius [1]. She reported that health care environment such as design, colors, art and sound are important to consider when planning for patients, healthcare providers and relatives. Color and lighting are important in hospital design [9]. The healthcare environment is described from a patient-centered perspective. Patients express that the healthcare environment is important for interaction improvements with healthcare providers [10]. Patient centered care [47] and the impact of art and design is described as vital parts in mental healthcare [48].

Health care providers in the present study perceived increased social interaction with colleagues by the use of photos through thoughts that come to mind in conversations. The social interaction domain with the themes; arising thoughts and conversations could be exemplified bythe excerpts; “positive for patients ... and myself ... to talk about ...; “a help to start a conversation”; “the photos create ... This is in line with previous research in which dialogues were used successfully with elderly persons [3,49]. When two people engage in a conversation, each person brings his or her own unique world and perception to the encounter. The dialogues are centred upon people’s knowledge and personal experiences, and offer a cognitive and emotional tool by which nurses and patients can communicate. The study shows that the use of art can be helpful in developing a dialectical relationship between people, and give health professionals different methods of communicating with patients. In controlled intervenetion studies dialogues inspired by paintings bring forth beneficial effects in elderly individuals such as decreasing blood pressure and physical well-being.The present study shows that the ward enrichments with photos provide a diversity of interesting topics to be discussed. This is in line with research that describes the perception of the healthcare environment from a patient-centered perspective. Patients express that the healthcare environment is important for interaction improvements with healthcare providers [10]. Still, there is a need to further develop art instruments for conversation to be used by health professional. Conversations related to photos could be one way to meet this need.

The average level of health professionals’ perception and expectation when describing the new aesthetic ward design was analysed according to health professionals’ motivation, emotional engagement and structure. It was clear from the results of the analyses that the new art interior design was associated with a positive perception by the participants. They were motivated, structured and emotionally engaged when describing the new enrichment of the surgical ward. Emotional investment in their engagement was (1.34) on a scale range from (0 - 2). Participants were structured when they describe the meaning of aesthetic enrichment of the surgical ward (0.5) on a scale range from (0 - 0.9) as well as motivated (9) on a scale range from (0 - 24). Adequate perception of the redesigned ward design process is a prerequisite for coping. To ensure coping all stages; emotional investment, structure and motivation, must be processed adequately. Poor structure could lead to the inability to relate to the situation. Poor control, when associated with negative emotions, could lead to poor coping and stress [31]. A factor that may help explain health professionals motivation, structure and emotional investment related to there shaped ward design is likely to be that health professionals look upon their work responsibilities in a more positive way. Another explanation could be that they compared their ward with non-redesigned wards at the hospital. In line with this reasoning is research about health care planning and the importance to take into consideration such as design, colors, art and sound for the patients, health care providers and relatives [1,9].

Health care design must not only support patient safety and quality in patient care, but also embrace patient, family, and caregivers in a psycho-socially supportive therapeutic environment in which a patient receives care that affects patient safety, patient satisfaction, staff efficiency, staff satisfaction, and organizational outcomes. Patients in a healthcare facility are often fearful and uncertain about their health, their safety, and isolated from normal social relationships. The health care environments further contribute to the stressful situation. Previous research points out that stress can cause a person’s immune system to be suppressed, reduce a person’s emotional resource, and affect recovery [5,50,51].

When photos were implemented at the surgical ward they provided a diversity of interesting topics to discuss. It would be hazardous though to make extensive generalisations from our findings. Especially to separate the effects of the photos from the effects of the interior design enrichment is hazardous. The enriched environment though, including photos, seems to nurture the communication between health professionals. These findings are in line withresearch that gives a description of a mode to get close to a painting [52,53].

It could not be ruled out that the present study has limitations. First and foremost, a bias could be the participant who did not answer the survey. They might be less positive to the reshaped ward design compared to those who participated. However, the cause of the issue was not difficulties gaining cooperation but with not being at work. Still, this bias cannot be ruled out. It is not clear how the non-participating group would affect the positive perception of the participating group of the reshaped ward design.

A study about aesthetic in hospitals in Norway reports that aesthetic and design are almost absent in Norwegian general hospitals and that the shaping of the environment is very important for the health and well-being of the patients [54]. The result from this study demonstrates the significance of the present study conducted in Finland with similar lack of aesthetic environmental enrichment in many hospitals.

Positive effects of aesthetic environmental enrichment have proven fruitful from the perspective of the patient regarding wellness and health. It might though be too early to state that aesthetic environmental enrichment is important for health professionals. Some research in the area points in positive direction. Investigations that focus on clients, their relatives and the staff in the area of interior design, show that being aware of the interior design influences the quality of life in terms of stress reduction [5-7]. The value of environmental aesthetic enrichment cannot be ignored. More research though; qualitative respectively quantitative controlled intervention studies are needed.

5. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The present study supported the view that an aesthetic environment, related to a person’s experiences and expectations, is of importance for health professionals. It is to be hoped that this study will contribute to the development of aesthetic hospital environments. We have to take into consideration the importance an aesthetic environment could have for patients, relatives and health professionals. There is a need to further develop instruments for shaping environmental enrichment to be used by health professionals working with patients in surgical wards. Similar opinion is reported about developing guidelines for good practice in the use of art in health care contexts [55].

Conversations between health professionals and between health professionals and patients are stimulated in an aesthetic environment, and should be regarded as important in hospital planning. We must though be cautious about making causal statements. However, the surgical ward environmental enrichment with photos, colors is an example to be used in ward design planning.

REFERENCES

- Lassenius, S.E. (2005) Rummet i vårdandets värld (The space in the world of caring). Åbo Akademi Company, Åbo.

- Wikström, B.M. (2002) Social interaction associated with visual art dialogs: a controlled intervention study. Aging & Mental Health, 6, 80-85.

- Wikström, B.M. (2003) Health professionals and paintings as a conversation tool. Applied Nursing, 16, 184- 188.

- Cintra, M. (2001) Art in health care buildings: Is any art good art. In: Dilani, A., Ed., Design and Health. the Therapeutic Benefits of Design, Elanders Swedish Press AB, Stockholm, pp. 303-311.

- Theorell, T. (2001) Physiological reactions to creative environments. In: Dilani, A., Ed., Design and Health. the Therapeutic Benefits of Design, Elanders Swedish Press AB, Stockholm, pp. 11-17.

- Wells-Thorpe, J. (2001) Design for enhanced recovery. In: Dilani, A., Ed., Design and Health. the Therapeutic Benefits of Design, Elanders Swedish Press AB, Stockholm, pp. 311-317.

- Wells-Thorpe, J. (2002) Better by design, understanding the healing environment. Helix, 23-27.

- Caspari, S., Erikssom, K. and Nåden, D. (2006) The aesthetic dimension in hospitals—An investigation into strategic plans. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43, 851-859. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.011

- Dalke, H., Little, J., Niemann, E., Camgoz, N., Sreadman, G., Hill, S. and Stott, L. (2006) Colourand lighting in hospital design. Optics & Laser Technology, 38, 343-365. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2005.06.040

- Douglas, C.H. and Douglas, M.R. (2005) Patient-centered improvements in health-care built environments: Perspectives and design indicators. Health Expectations, 8, 264-276. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2005.00336.x

- Maslow, A.H. and Mintz, N.L. (1956) Effects of esthetic surroundings: Initial effects of three esthetic conditions upon perceiving energy and well-being in faces. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 41, 247-254. doi:10.1080/00223980.1956.9713000

- Strickley, T. (2010) A report from an arts and health consultation and evaluation. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 1, 321-331. doi:10.1386/jaah.1.3.321_7

- Pattison, H.M. and Robertson, C.E. (1996) The effects of ward design on the well-being of post-operative patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23, 820-826. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb00056.x

- Staricoff, R.L., Wright, M., Loppert, S. and Scott, J. (2001) A study of the effects of the visual and performing arts in healthcare. Hospital Development, 32, 25-28.

- Lawson, B. and Wells-Thorpe, J. (2003) The architectural healthcare environment and its effects on patient health outcomes. HMSO, Norwich.

- Eisen, S. (2005) Artfully designed pediatric environments. Doctoral dissertation, A &M University, Texas.

- Edvardsson, D., Sandman, P.O. and Rasmusson, B. (2005) Sensing an atmosphere: a tentative theory of care settings. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 19, 344- 353. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00356.x

- Antonowsky, A. (1991) Hälsans mysterium (The mystery of health). Natur och Kultur, Köping.

- Aristoteles, (1988) Den nikomachiska etiken (The Nicomachic Ethic). Daidalos Company, Göteborg.

- Martin, A. (1998) Beauty is the mystery of life. In: Beckley, B. and Shapiro, D., Eds., Uncontrollable Beauty, toward a New Aesthetics, Allworth Press, New York, 339- 402.

- Morgan, R.C. (1998) A sign of beauty. In: Beckley, B. and Shapiro, D., Eds., Uncontrollable Beauty, toward a New Aesthetics, Allworth Press, New York, 75-82.

- Bullough, E. (1957) Aesthetics, lectures and essays. Bowes & Bowes, London.

- Gardner, H. (1973) The arts and human development: A psychological study of the artistic process. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Crose, B. (1912) Estetisktbrevarium (Breviary of Aesthetics). Stockholm/Roma, Italica.

- Bell, C. (1914) Art. Chatto & Windows, London.

- Hirn, Y. (1902) Konstens ursprung: En studie öfver den estetiska värksamhetens psykologiska och sociologiska orsaker (A study of aesthetical experiences; psychologycal and sociological causes). Söderström Company, Helsingfors.

- Nightingale, F. (1992) Notes on nursing. Harrison and Sons, London.

- Wikström, B.M., Ekvall, G. and Sandström, S (1994) Stimulating the creativity of elderly institutionalized women through works of art. Creativity Research Journal, 7, 171-182. doi:10.1080/10400419409534522

- Bygren, L.O., Konlaan, B.B. and Johansson, S.E. (1996) Attendance at cultural events, reading books or periodicals, and making music or singing in choir as determinants for survival: Swedish interview survey of living conditions. British Medical Journal, 313, 1577-1580. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1577

- Shalit, B. (1978) Perceptual organisation and reduction questionnaire-administration and scoring. FOA-Report C 55021-H6, National Defense Research Institute, Stockholm.

- Shalit, B. (1979) Perceptual organisation and reduction questionnaire-validity. FOA-Report C 55036-H6, National Defense Research Institute, Stockholm.

- Shalit, B. and Carlstedt, L. (2001) The perception of enemy threat. a method for assessing the coping potential. FOA-report C 55063-H4, National Defense Research Institute, Stockholm.

- Manguel, A. (2000) Reading pictures: a history of love and hate. Random House, New York.

- Child, I.L. (1965) Personality correlation of aesthetic judgment in college students. Journal of Personality, 33, 476-511. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1965.tb01399.x

- Berlyne, D.E. (1971) Aesthetics and psychobiology. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York.

- Sandström, S. (1977) A common taste in art, an experimental attempt. Swedish Humanistic Research Council, Aris, Lund.

- Wikström, B.M., Theorell, T. and Sandström, S. (1993) Medical health and emotional effects of art stimulation in old age. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 60, 195-206. doi:10.1159/000288693

- Wikström, B.-M. Theorell, T. and Sandström, S. (1992) Psychophysiological effects of stimulation with pictures of works of art in old age. International Journal of Psychosomatics, 39, 68-75.

- Sandström, S. (1983) Se och uppleva (Seeing and perceiving). Kalejdoskop, Åhus.

- Wikström, B.M. (2001) Works of art dialogues: An educational technique by which students discover personal knowledge of empathy. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 7, 24-29. doi:10.1046/j.1440-172x.2001.00248.x

- Wikström, B.M. (2004) Older adults and the arts, the importance of aesthetic forms of expression in later life. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 30, 30-36.

- Sandström, S. (1997) Intuition och åskådlighet (Intuition and clearity).Carlssons Förlag, Stockholm.

- Morse, J.M. and Field, P. (1996) Nursing research. The application of qualitative approaches. Chapman & Hill, London.

- Manen, V.J. (1983) Reclaiming qualitative methods for organizational research: A preface. In: Manen, V.J., Ed., Qualitative Methodology, Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, 9-18.

- Kvale, S. (1989) Issues of validity in qualitative research. Studentlitteratur, Lund.

- Williams, R.J. (2008) The declaration of Helsinki and public health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86, 650-651. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.050955

- Daykin, N., Byrne, E., O’Conner, S. and Soteriou, T. (2008) The impact of art, design and environment in mental healthcare: A systematic review of the literature. Perspectives in Public Health, 128, 85-94. doi:10.1177/1466424007087806

- Frampton, S.B., Gilpin, L., Charmel, P.A. (2003) Putting patients first: Designing and practicing patient-centered care. Johan Wiley & Sons, San Francisco.

- Wikström, B.-M. (2000) Visual art dialogues with elderly persons: effect on perceived life Situation. Journal of Nursing Management, 8, 31-37. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2834.2000.00154.x

- Theorell, T. and Hasselhorn, H.M. (2002) Endocrinological and immunological variables sensitive to psychosocial factors of possible relevance to work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Work & Stress: An International Journal of Work, Health & Organisations, 16, 154- 165. doi:10.1080/02678370210150837

- Theorell, T. (1995) Om den psykosociala miljön och hur den samvarierar med Hälsoparametrar (The psychosocial environment and the connection to health parameters), In: Sivik, L. and Theorell, T., Eds., Psykosomatisk Medicin, Studentlitteratur, Lund.

- Weitz, M. (1976) Art: Who needs it? Journal of Aesthetic Education, 10, 19-27. doi:10.2307/3332006

- Weir, H. (2010) You don’t have to like them: Art, tate modern and learning. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 1, 93-110. doi:10.1386/jaah.1.1.93/1

- Caspari, S., Eriksson, K. and Nåden, D. (2011) The importance of aesthetic surroundings: a study interviewing experts within different aesthetic fields. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 25, 134-142. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00803.x

- White, M. (2010) Developing guidelines for good practice in participatory arts-inhealth-care contexts. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 1, 139-155.