Current Urban Studies

Vol.2 No.1(2014), Article ID:44415,12 pages DOI:10.4236/cus.2014.21007

Dispelling Stereotypes… Skate Parks as a Setting for Pro-Social Behavior among Young People

Lisa Wood1, May Carter2, Karen Martin1

1Centre for the Built Environment and Health, School of Population Health, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia

2PlayScape, Perth, Australia

Email: lisa.wood@uwa.edu.au

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 12 February 2014; revised 12 March 2014; accepted 20 March 2014

Abstract

Issue Addressed: Skate parks not only provide a venue for leisure and physical activity, but can also act as an important social space for young people (Jones, 2011). However, skate parks are often subjected to negative community stereotyping (Goldenberg & Shooter, 2009; Bradley, 2010; Weston, 2010, Taylor & Khan, 2011), and there has been a lack of empirical evidence to date to refute or support conjecture about the presence of antior pro-social behaviors. Methods: A community survey gathered data on use and perceptions of a skate park within an inner metropolitan suburb of Western Australia. Respondents (n = 387) were asked about the frequency at the skate park of a range of potentially occurring behaviors of both an anti-social (e.g. graffiti, conflict) and pro-social (e.g. socialising, teaching) nature. Observational data of skate park use were also collected. Results: Pro-social behaviours were much more likely to be reported as frequently occurring, with all six of the pro-social behaviors (cooperation, learning from others, socialising with friends, respecting others, taking turns, teaching and helping) noted as occurring often by more than 50% of the respondents. The anti-social behaviours asked about in the survey fall within three thematic categories relating to physical space (egcrowding, collisions and injuries); property damage (eglittering, graffiti and vandalism); and drug use (smoking, drinking alcohol and illicit drug taking). Of these, behaviors relating to shared use of the physical space were more likely to be reported as occurring often or sometimes, in part reflecting the popular use of the relatively small skate park area. Overall, anti-social behaviors were more likely to be reported as rarely or never occurring compared with pro-social behaviors. Conclusions: Concerns about undesirable social behavior often underlie opposition to skate parks or provision for skaters in cities and suburbs. However, actual evidence supporting these assertions is scant, and in this study, pro-social behaviors were far more commonly observed than anti-social behavior. Considered skate park location and planning, and engagement of young people in their design can minimise many perceived problems. More broadly, the visible presence of skate parks and other youth amenity in our neighbourhoods, towns and cities, powerfully signals to young people that they too are welcome and a part of local place identity.

Keywords:Skate Park; Urban Planning; Adolescents; Healthy Neighbourhoods; Social Inclusion

1. Introduction

The growing need for autonomy during adolescence and increasing socialisation encourage teenagers to spend more time away from home, but where can they go? As the typical playground caters to younger children, groups of adolescents using parks and public places are often stereotyped as being “up to no good”. While recognising that skate parks don’t meet the needs of all young people, there are usually few other community spaces where they can “hang out”, despite this being a vital part of adolescent social development {Chipuer, 2000 #362}(Chipuer & Pretty, 2000). Yet provision of these facilities is often under threat from community opposition, and some established skate parks have had to make way for retail and housing development (Save Claremont Skatepark, 2013).

While there is much focus on organised and team sports to encourage children to be physically active, a significant proportion of children and adolescents engage in non-structured physical and recreational activities. Australian data indicate that youth participation in activities such as skateboarding, in-line skating, rollerblading and scootering is now close to exceeding participation in organised sports (ABS, 2012).

Skateboarding is more than just a form of physical activity or way to pass time, as it also embodies a “culture” that participants identify with (Jones, 2011). Although commercialization has appropriated this culture to some extent through branded skate clothing and corporate sponsorship of competitions, other aspects of the skateboarding culture are evident in the way skaters interact with other, and are increasingly expressed through their use of digital media to share images, video clips and reports of mastered tricks with each other (Jones, 2011).

In a 2009 survey undertaken by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 54% of children had participated in skateboarding, rollerblading or scooter riding in the previous two weeks, with 60% having participated in at least one organised sport out of school (ABS, 2012). Although skateboarding is often stereotyped as a teenage male domain, recent WA data indicated that among primary school children aged 10 - 12 years, 33.8% of boys and 18.3% of girls had skateboarded in the week prior to the survey (Martin, Rosenberg et al., 2010). Skateboarding by adults, particularly among young adults is also not uncommon, with a recent US report classifying it as the third favored youth outdoor activity for ages 6 - 24, and the fifth favored for ages 25 and above (The Outdoor Foundation, 2012), whilst in Australia, the formation of professional bodies such as “Skate Australia” through the federally funded Australian Sports Commission (Skate Australia, 2009), has enhanced the legitimacy of skateboarding for people of all ages.

Despite its popularity, skateboarding often suffers negative stereotypical associations with youth counterculture, graffiti (Taylor & Khan, 2011) and anti-social behaviour (Goldenberg & Shooter, 2009; Weston, 2010). Perceptions of skaters and their behaviour have also been tarnished in some instances by damage incurred by skateboarding on public surfaces (Aperio Consulting, 2005; Bradley, 2010). Indeed one of the arguments for purpose designed skate parks is that it can deflect skateboarding from mixed-use public areas (Woolley, 2009) because of the sport’s perceived incompatibility with other pursuits undertaken in these public spaces (Németh, 2006). Restrictive signages or bans on skateboarding are now common sight in the public realm, and this can serve to subtly reinforce community perceptions about the “appropriateness” of such an activity.

One of the prevalent oppositions to skate parks does not relate to skating per se, but rather to the fact that they are venues where young people “hang out”, with skate parks often doubling an informal space where skating and non-skating youths congregate (Weller, 2006; Bradley, 2010; Taylor & Khan, 2011). “Hanging-out” is sometimes frowned upon by members of the broader community who believe it is an unproductive pursuit and encourages antisocial behaviour (Rogers & Coaffee, 2005; Woolley, 2009; Bradley, 2010). Despite this perception, “hanging-out” is an important part of adolescent social development (Passon, Levi et al., 2008; Bradley, 2010). It has also been argued that spaces for adolescent to gather need to be provided in the public arena (Owens, 2002) as it may actually be a lack of things to do which fuels delinquent behaviour (Caldwell & Smith, 2006).

Subsequently, the potential positive outcomes associated with skateboarding or skate parks are often overlooked, and the benefits of skateboarding settings for youth development have rarely been the subject of empirical research (Goldenberg & Shooter, 2009). Nonetheless, a trawl through the literature identifies a variety of positive outcomes potentially associated with skateboarding. For example, social development through peer-topeer skill acquisition and creativity are fostered through skateboarding, and the arts of cooperation, negotiation and compromise are learnt informally, in contrast to the structured rules of organised sports. Skateboarding is also reported to require physical exertion equivalent to between 5 and 12.5 times that of the resting metabolic rate (Ainsworth, Haskell et al., 2000); thus, these activities also contribute to important moderate and vigorous physical activity for participants. Potential mental health benefits of skateboarding such as building self-esteem, social competence and respect for others are cited in the literature (Owens, 2002; Bradley, 2010) and collaborative activities such as developing and maintaining community sites have also been reported (Moore & Carter, 2011; Jenson, Swords et al., 2012).

Although negative stereotypes of skateboards in the public realm often prevail, the presence of skateboarders can actually yield some benefits to the wider community. For example, Jensen emphasises that the creativity and entrepreneurial nature of the skating scene in England have been harnessed to reinvigorate fading areas of cities and councils, and its presence used to provide natural surveillance along otherwise threatening walkways and paths (Vivoni, 2009; Jenson, Swords et al., 2012).

Given the polarised community opinion that sometimes plagues skate parks, this paper examines. Pro-social and anti-social behaviors are observed within a skate park in an inner city suburb of Perth.

2. Methods

Ethics approval for this research was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University undertaking the research.

The study investigated patterns of usage at a suburban skate park in a central suburb of Perth using survey and observational data collection methods. The study skate park is relatively small, comprising only a double bowl, spine, box and rail, with the skateable area measuring approximately 400 square metres. Supporting facilities include shaded seating and a drinking fountain. It is used by skateboarders, BMX and scooter riders, and draws users from within the immediate suburb and more broadly, and is well located in terms of public transport access (See Figure 1). The skate park is co-located in 2.5 ha of parkland and is surrounded on one side by a major traffic route. Other parkland elements include open lawn, tennis courts, off-street parking and several community buildings.

Figure 1. The study skate park.

Development of the survey and observational tool were informed by a review of published studies undertaken in skate park settings (Bradley & Stinson, 2008); (Bradley, 2010); (Shannon & Werner, 2008), as well as the grey literature (Aperio Consulting, 2005). At the time of instrument development, published studies were more often of a qualitative or observational nature, hence the inclusion of grey literature for sourcing of potential survey items was useful.

2.1. Survey Data Collection

The survey was developed as on online survey, with an identically worded paper version available at the skate park when the research team was present to undertake observation. The online survey was promoted via the local council, key stakeholders and flyers in the local area. The majority of surveys (88%) were completed online. Of the 387 respondents, 275 (71.6%) identified themselves as skate park users.

The survey instrument (refer to http://www.sph.uwa.edu.au/research/cbeh/projects/childsplay for survey) was designed to capture data from both direct users of the skate park, as well as those who had visited as companions or spectators, and from local community members who may have observed usage of the park. The survey items included questions about frequency of visitation to the skate park, reasons for attending the skate park, and whether they themselves used a skateboard, bicycle or scooter at the skate park. Respondents were asked about the frequency of a range of behaviors that potentially occur at skate parks as identified from the literature. They were asked to rate frequency on likert scale (often, sometimes, rarely, never) for 19 potential behaviors, both of an anti-social (such as graffiti, conflict, crowding and collisions) and pro-social (such as socialising, teaching, learning) nature. The survey also asked respondents about what they might want to see added to the skate park should it be redeveloped—these items were identified from the literature and included features such as seating areas, water fountains, shade and lighting. Responses to these questions were rated on a 5 point Likert scale (very desirable through to very undesirable).

2.2. Observation Data Collection

The observation tool was designed to collect basic data on types and patterns of skate park usage, and drew particularly on the methodology and measures used by Bradley et al.’s study of an urban skate park in Queensland (Bradley & Stinson, 2008; Bradley, 2010). Each observation session incorporated a trained researcher sitting approximately 5 - 10 metres from the skate park observing and recording the demographics and behaviors of the skate park users. Each observation session lasted two hours (with the exception of one that was curtailed by heavy rain). For each observation session (n = 6), the observer recorded; 1) the total number of observed skate park users (including spectators and supervising parents/adults), 2) gender and estimated age category of each skate park user, 3) type of activity (skateboard, scooter, BMX bike, sitting watching); and 4) whether they were attending the skate park alone or in the company of others.

In total, 11 hours of observational data was collected. The observational data was collected by three members of the research team; with all three visiting on the first occasion to establish inter-rater consistency. The observation sessions were scheduled at different times of the week and day (before school, after school, weekend, daytime non-school day) over a two week period.

Data was analysed using SPSS version 20.0. Descriptive statistics were generated using SPSS.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Data

The vast majority of survey respondents were male (93%). Of those who reported themselves as skate park users, the majority were skateboarders (73%), followed by BMX riders (13%) and scooter riders (3%). The median age of respondents was 18 years. Approximately half (52%) of the responding skaters/riders had five or more years’ experience in skating or riding and the vast majority (95%) participated in their chosen activity at least once a week, with almost one quarter participating daily (23%) (Table 1).

Two thirds (63%) of respondents reported visiting the skate park at least once every few months. As well as using the skate park for skating or riding, users visited the skate park to watch other people skate (36%) or to socialise with friends (51%). One third (36%) of respondents lived within approximately five kilometres of the

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents*.

*Does not add to 100% due to missing data for some respondents.

skate park.

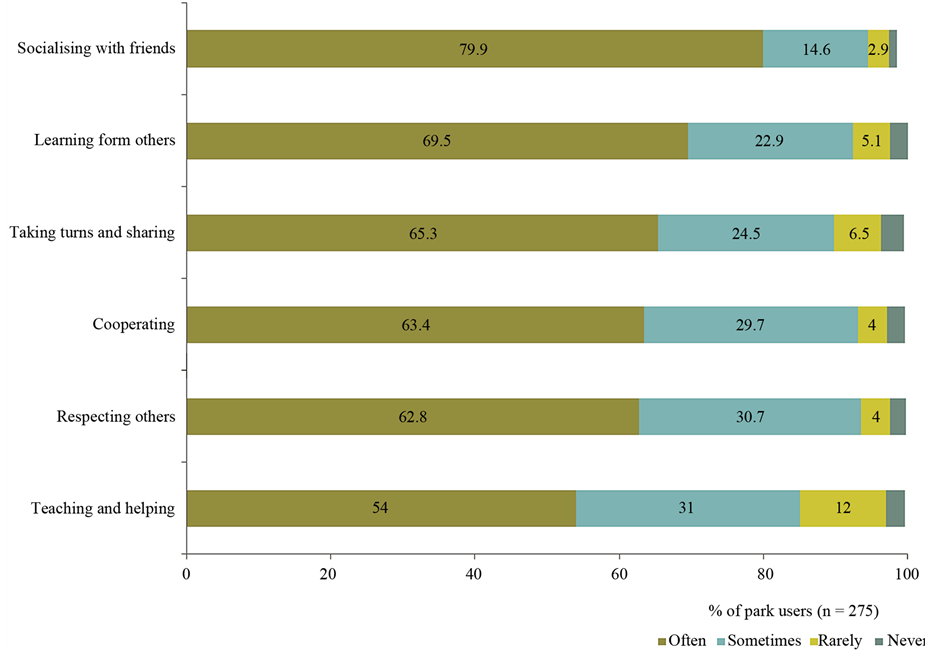

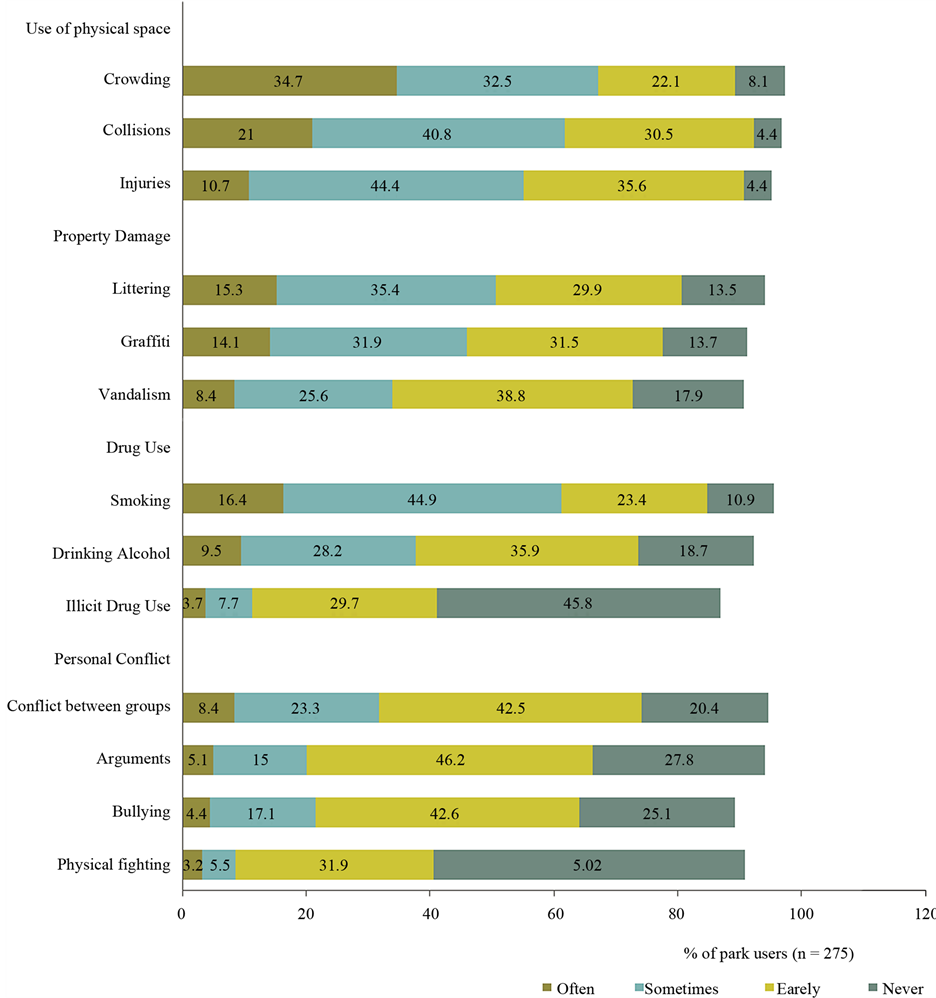

Pro-social behaviors were more frequently reported by respondents than anti-social behaviors (see Figures 2 and 3).

Not only were pro-social behaviors reported more frequently overall by survey respondents, but pro-social behaviors were much more likely to be rated as occurring often. Co-operative behaviors such as socialising with friends (80%), learning from others (70%) teaching and helping (54%), sharing and taking turns (65%), cooperating (63%), and respecting others (63%) were reported to occur often. Corresponding anti-social behaviors relating to personal conflict were reported much less frequently, with fewer than 10% of respondents indicating the often occurrence of conflict between groups, arguments, bullying or physical fighting.

The other anti-social behaviors asked about in the survey fall within three thematic categories; these relate to physical space (crowding, collisions and injuries); property damage (littering, graffiti and vandalism); and drug use (smoking, drinking alcohol and illicit drug taking). Behaviors relating to use of the physical space were more likely to be reported as occurring often or sometimes: crowding (77%), collisions (62%) and injuries (55%).

Behaviors relating to property damage were reported to occur often or sometimes by a relatively high proportion of respondents—littering (51%); graffiti (46%) and vandalism (34%).

Unfortunately the wording of questions relating to property damage did not elucidate whether respondents actually witnessed this occurring or noted its after-effects, which could inflate the incidence of occurrence as multiple respondents may be reporting a single act of property damage such as graffiti.

Of the behaviors relating to drug use, smoking was the most common, with around one in six respondents (16%) indicating that smoking occurred often at the skate park, and half responding with sometimes (45%). Ob-

Figure 2. Frequency of positive social behaviours reported by respondents.

serving people drinking alcohol was less frequently reported, although one in ten respondents (9.5%) reported observing it often, and observing it sometimes was reported by almost one-third of respondents (28%). Reported observation of illicit drugs was uncommon, with a relatively small number of respondents reporting they often (4%) or sometimes (8%) observed use. As the skate park is attended by some adult skaters and spectators, it is not known to what extent the preceding observations related to adult or adolescent smoking, alcohol or drug use.

The high proportion of respondents referring to observed socialising behavior (80% saw this often) was mirrored in the observational data, which noted that 65% of people observed attending the skate-park were in groups of two or more.

In addition, 69% of survey respondents indicated that they would like places to hang out with friends added to the skate-park area. Other desired features were places to sit and rest (90%).

3.2. Observation Data

In total, 113 visitors were observed at the Subiaco Skate park during the observation period and recorded observation data are collected on 97 skate park users. Most of the users were male (91%) and 35% of users were in the age group of 13 - 16 years, followed by 16 years (26% and 8 - 12 years (18%). The most common activity was skating (55%), followed by scooter and riding. The majority of the users (65%) visited in groups, with one third of user being classified as adults and the two other thirds were children adults.

Of the observed users of the skate park 26% of were classified as over 16 years, 35% as 13 - 16 yrs and 18% 9 - 12 yrs. The most commonly observed activities were skating (55%), scooter (18%), bike riding (11%) and sitting and watching others (11%). The gender profile of skate park users (n = 97) observed in the observational data collection periods was similar to the survey respondent mix, with 91% of the people using the skate-park male.

During the observation periods, crowding and a small amount of litter were the only anti-social behaviors observed. Pro-social behaviors were witnessed during each of the observational periods, with taking turns, social-

Figure 3. Frequency of negative social behaviours reported by respondents.

ising with others, and respecting others the most commonly noted behaviors. On two occasions younger children were observed to be watching older more experienced skateboarders as a way of learning skating techniques.

4. Discussion

While not nearly as prevalent as playgrounds and sporting ovals, skate parks are stereotypically regarded as an appropriate form of recreational facility for young people. Yet the availability and quality of this type of facility is sporadic in Australia (Kellett & Russell, 2009) and opposition to the establishment or existence of skate parks often prevails (Taylor & Marais, 2011). Skate parks are also often stereotyped as a beacon for problematic behaviour (Aperio Consulting, 2005; Woolley, 2009; Bradley, 2010; Taylor & Khan, 2011), but our findings suggest that there is a disjuncture between community perceptions and reality. Most frequently occurring behaviors reported by survey participants in this study were positive, with reports of pro-social behaviors occurring “often” and “sometimes” outnumbering anti-social behavior reports by 2.3 to 1 (91% pro-social vs. 39% antisocial). The findings add support to an emerging body of literature pertaining to relative absence of anti-social behavior in skate park settings (Bradley, 2010; Taylor & Khan, 2011), and the presence of informal norms which often regulate the behavior of skate park users (Beal, 1996).

The pro-social behaviors reported in this study took a number of forms, and included socialising with friends, learning from others, teaching and helping, sharing and taking turns, cooperating and respecting others. This is consistent with other studies purporting that skate parks can provide opportunities for meaningful identify development, camaraderie and social integration that can lead to positive youth development (Bradley, 2010). Furthermore, activities such as skateboarding and BMXing are challenging and require effort and concentration from those undertaking them (Trainor, Delfabbro et al., 2010)—this was evident also in observations undertaken by the research team at the skate park, where teenagers were seen persisting and concentrating as they sought to master a new “trick”, with “how to land a trick” often taught informally to each other. Somewhat unique to the skate park context is the extent to which they provide opportunities for “legitimate peripheral participation” (Jones, 2011) which not only facilitates learning through observation of skateboarding techniques, but just as importantly, learning and modelling of turn-taking, peer encouragement and persistence.

Similar to findings from Bradley, skate park users in this study reported going to the skate park to watch others and to socialise with friends as well as skate/ride (Bradley, 2010). The importance of skate parks as a social outlet has been highlighted by Taylor, who found the acceptance, assistance and social capital developed in these settings can sometimes fill voids in other areas of users’ lives, where their emotional or physical needs may not be met (Taylor & Khan, 2011).

In this study, the most commonly reported negative behaviors were not of an anti-social nature but related to collisions and crowding. This reflects the high usage of this relatively small skate park area, which comprises only a small double bowl and box. Collisions and crowding are both factors that can be addressed to some extent through good design, but are also dictated by the small size of the current skate park relative to the volume of users. Interestingly, Petrone suggests that skate park conflict between users is one of the ways in which young people learn about spatially appropriate behaviour (Petrone, 2010). This is borne out by the fact that 86% of skate park users surveyed did not live in the suburb where the skate park was located and, and reported travelling to the skate park specifically to use it.

While this study was limited to the perceptions of skate park users, there is also a need for research that objectively examines whether skate parks are in fact associated with higher levels of anti-social behavior, disorderly conduct or property damage as is sometimes presumed by skate park opponents. A Western Australian study (Taylor & Khan, 2011) found no relationship between the cost or incidence of graffiti at schools and their proximity to skate parks. In this study we were not able to obtain data from local government or police to support or refute this objectively, although anecdotal evidence indicated that there had only been small but vocal “squeaky wheel” negativity expressed to council about the existing skate parks in the study suburb.

Nonetheless, sometimes the negative views about vandalism, litter or evidence of drinking at a skate park are well founded, with a “bad name” more likely to arise when a skate park has been located in out of the way, deserted or poorly lit areas (Bradley & Stinson, 2008; Jenson, Swords et al., 2012), out of everyday community view. Conversely, locating skate parks to maximise the presence of natural surveillance can reduce the likelihood of anti-social behavior (Bradley, 2010).

In the case of the skate park in this study, it possesses a number of the features that are arguably protective against anti-social behavior. The park is prominently located on the corner of two well-trafficked streets which means there is significant passive surveillance of the area by motorists, pedestrians and cyclists. This is in stark contrast to the British “Exhibition Skate park” which Jenson (2012) uses as a case study to illustrate the necessity of accessibility and natural surveillance to successful skate park design: despite the Exhibition Skate park’s location 10 minutes from two metro stops, it is isolated by a large motorway which renders it accessible by underpass only, and surrounds it with embankments which block it from view. This is said to have resulted in negative perceptions of the park and reduced use by both skaters and the general public (Jenson, Swords et al., 2012).

In addition to the natural surveillance afforded by a more accessible and visible location, this also sends a more positive symbolic message to young people than if facilities for them are segregated or confined to isolated or less desirable locations. As Nemeth notes, such an approach denies young people of their right to representation in the public realm, rendering them invisible and stifling their engagement with the broader community (Németh, 2006).

The skate park also had a number of other good skate park design features identified in the literature. These include a central location with easy access to public transport and facilities (Woolley & Johns 2001; City of Norwood, 2006); regular maintenance (Buskens, 2005; City of Norwood, 2006; Thompson, 2010), lighting (City of Norwood, 2006); and integration or proximity to other recreational facilities (City of Norwood, 2006; Thompson, 2010). The skate park is not enclosed or fenced, and this is also an identified aspect of good design in the literature (Vivoni, 2009). In some countries however, there is a trend towards enclosed fencing of skate parks (see Figure 4) and other youth recreational amenity, and whilst this is often done in the name of vandalism prevention, it is visually unwelcoming and can paradoxically convey that a neighbourhood is not safe Martin and Wood (2013). Moreover, an enclosed fenced skate park precludes the opportunity for informal spectating for passers-by that is popular when they are more integrated into a broader public realm (such as the Geelong Youth Activity Area (Urban Design Protocol, 2013)) which has been designed as a public plaza and is located on the Geelong waterfront adjacent to the CBD.

Although the literature identifies some of the design elements conducive to a good skateboarding environment, as aptly noted by Jones and Graves (2000), skateboaders do not use skate parks in the same generic way that a tennis court or baseball field is used (Jones & Graves, 2000). Thus, skate park design needs to be responsive to the needs and preferences of those who will use it, with design also supporting important outcomes relating to social interaction and sense of place (Goldenberg & Shooter, 2009).

Lynch & Ogilvie (1999) emphasise that providing amenities alone is not conducive to a reducing youth antisocial behaviors, and that this is best achieved when facilities are appropriated by users and seen as "really theirs” (Lynch & Ogilvie, 1999). A study in the Isle of Wright which afforded skate park users the opportunity to liaise with the broader community in the planning and maintenance of their skate park, highlights the benefits of fostering civic engagement and a sense of ownership among users (Weller, 2006). Other authors also describe the attachment skaters invest in parks and skate spots, and the sense of community and responsibility which this can foster (Vivoni, 2009; Jenson, Swords et al., 2012; Vivoni, 2013).

Figure 4. Fenced skate park—New York.

5. Limitations

As this research was undertaken at only one skate park site, findings may not be generalizable to other skate park or community contexts, although the congruence with many themes in the literature suggests that the skate park in this study is not atypical. As the online survey was in part promoted through formal and informal skateboard organisations and their social network, the respondents most likely depict an over-representation of skateboarders who may be more likely to report pro social behavior. The male gender skew of respondents is fairly typical of skate parks users; another Australian study has reported similar ratio of males to females. (Bradley, 2010) This survey had more adult respondents compared with our observation of actual skate park users (only approx. 14% of users observed were adult compared with 51% of survey respondents), and this is supported by observational data from a study of Queensland skate parks (Bradley, 2010).

The reported observations of both pro and anti-social behavior are self-reported hence are subject to perception and reporting bias, and the small amount of researcher observational data that was able to be collected was not sufficient to provide reliable verification, although it is pertinent to note that the bulk of behaviors observed by researchers during the observation periods were of a pro-social nature. The reported observations of smoking, alcohol and drug use should be interpreted with caution as it was not possible to tell from the question wording whether it was young people or adults who were observed undertaking these behaviors. Future research could incorporate the use of interviews or focus groups to establish further details about pro and anti-social behaviors.

6. Conclusions

This survey sought to explore the frequencies of pro-social and antisocial behaviors within an inner city urban skate park observed by skate park users and the community. Overall, this study found that pro-social behaviors were much more frequently observed than anti-social behaviors, highlighting the value of this amenity in fostering the development of young peoples’ social skills, self-esteem, cooperation and respect for self and others.

Concerns about undesirable social behavior often underlie opposition to skate parks or provision for skaters in cities and suburbs. However, actual evidence supporting these assertions is scant, and in fact, “the lack of things for young people to do” is a greater risk for undesirable behavior. Good placement and planning of skate parks can minimise many of the perceived problems.

Young people need things to do and places where they are free to be themselves within our cities and suburbs —this needs to include not only facilities and public areas that cater to more traditional and formal sport, but also those that provide for skateboarding as a popular and healthy form of recreational and social activity.

Acknowledgements

Kate Ryan and Sarah French are gratefully acknowledged for their earlier involvement in undertaking this research, Estée Lambin for her assistance with the literature review, and Catherine Coletsis for her patience with referencing and formatting. Authors Wood and Martin are both supported by research fellowships from the Western Australian Health Promotion Foundation (Healthway).

References

- ABS (2012). 4901.0—Children’s Participation in Cultural and Leisure Activities, Australia. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4901.0Main%20Features6Apr%202012?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4901.0&issue=Apr%202012&num=&view

- Ainsworth, B., Haskell W., Whitt M., Irwin M., Swartz A., Strath S., et al. (2000). Compendium of Physical Activities: An Update of Activity Codes and MET Intensities. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise, 32, S498-S516.

- Aperio Consulting (2005). The Urban Grind: Skateparks: Neighborhood Perceptions And Planning Realities.

- Beal, B. (1996). Alternative Masculinity and Its Effects on Gender Relations in the Subculture of Skateboarding. Journal of Sport Behavior, 19, 204-220.

- Bradley, G. (2010). Skate Parks as a Context for Adolescent Development. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25, 288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0743558409357236

- Bradley, G., & Stinson, K. (2008). Skaters’ Paradise? A Study of Gold Coast City Skate Parks and Their Users. Gold Coast: Gold Coast City Council.

- Buskens, N., & Harbottle, R. (2005). Skate Park Operations Manual. Melbourne: YMCA Victoria.

- Caldwell, L., & Smith, E. (2006). Leisure as a Context for Youth Development and Delinquency Prevention. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 39, 398-418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1375/acri.39.3.398

- Chipuer, H. M., & Pretty, G. H. (2000). Facets of Adolescents’ Loneliness: A Study of Rural and Urban Australian Youth. Australian Psychologist, 35, 233-237. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00050060008257484

- City of Norwood, P. S. P. (2006). Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED): Guidelines for Local Government. Norwood.

- Goldenberg, M., & Shooter, W. (2009). Skateboard Park Participation: A Means-End Analysis. Journal of Youth Development, 4, 37-48.

- Jenson, A., Swords J., & Jeffries, M. (2012). The Accidental Youth Club: Skateboarding in Newcastle-Gateshead. Journal of Urban Design, 17, 371-388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2012.683400

- Jones, R. (2011). Sport and Re/Creation: What Skateboarders Can Teach Us about Learning. Sport, Education and Society, 16, 593-611. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.601139

- Jones, S., & Graves, A. (2000). Power Plays in Public Space: Skateboard Parks as Battlegrounds, Gifts, and Expressions of Self. Landscape Journal, 19, 136.

- Kellett, P., & Russell, R. (2009). A Comparison between Mainstream and Action Sport Industries in Australia: A Case Study of the Skateboarding Cluster. Sport Management Review, 12, 66-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2008.12.003

- Lynch, M., & Ogilvie, E. (1999). Access to Amenities: The Issue of Ownership. Youth Studies Australia, 18.

- Martin, K., Rosenberg, M., Miller, M., French, S., McCormack, G., Bull, F., Giles-Corti, B., & Pratt, S. (2010). Move and Munch Final Report. Trends in Physical Activity, Nutrition and Body Size in Western Australian Children and Adolescents: The Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (CAPANS) 2008.

- Martin, K., & Wood, L. (2013). “We Live Here Too”… What Makes a Child Friendly Neighbourhood? In R. D.-C. A. C. C., Elizabeth Burton (Ed.), Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, in press.

- Moore, T., & Carter, M. (2011). Focus on Fleming Reserve, High Wycombe. Australasian Parks and Leisure, 14, 10-14.

- Németh, J. (2006). Conflict, Exclusion, Relocation: Skateboarding and Public Space. Journal of Urban Design, 11, 297-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13574800600888343

- Owens, P. (2002). No Teens Allowed: The Exclusion of Adolescents from Public Spaces. Landscape Journal, 21, 156.

- Passon, C., Levi, D., & del Rio, V. (2008). Implications of Adolescents’ Perceptions and Values for Planning and Design. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 28, 73-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08319236

- Petrone, R. (2010). You Have to Get Hit a Couple of Times: The Role of Conflict in Learning How to Be a Skateboarder. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 119-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.05.005

- Rogers, P., & Coaffee, J. (2005). Moral Panics and Urban Renaissance. City, 9, 321-340.

- Save Claremont Skatepark (2013). Save Claremont Skatepark. https://www.facebook.com/pages/Save-claremont-Skatepark/148389431901114

- Shannon, C., & Werner, T. (2008). The Opening of a Municipal Skate Park: Exploring the Influence on Youth Skateboarders’ Experiences. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 26, 39-58.

- Skate Australia (2009). Skate Australia Independent Submission to the Panel for the Independent Review into Sport. http://www.skateaustralia.org.au/images/stories/skate_australia/documents/pdf/Skate_Australia_Independent_Sport_Panel_Submission.pdf

- Taylor, M., & Khan, U. (2011). Skate-Park Builds, Teenaphobia and the Adolescent Need for Hang-Out Spaces: The Social Utility and Functionality of Urban Skate Parks. Journal of Urban Design, 16, 489-510.

- Taylor, M., & Marais, I. (2011). Not in My Back Schoolyard: Schools and Skate-Park Builds in Western Australia. Australian Planner, 48, 84-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2011.586142

- Taylor, M. F., & Khan, U. (2011). Skate-Park Builds, Teenaphobia and the Adolescent Need for Hang-Out Spaces: The Social Utility and Functionality of Urban Skate Parks. Journal of Urban Design, 16, 489-510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2011.586142

- The Outdoor Foundation (2012). Outdoor Recreation Participation Topline Report 2012. Boulder, CO: The Outdoor Foundation.

- Thompson, F. (2010). Skateboard Jungle. Newcastle: The Newcastle Herald.

- Trainor, S., Delfabbro, P., Anderson, S., & Winefield, A. (2010). Leisure Activities and Adolescent Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 173-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.013

- Urban Design Protocol (2013). Geelong Youth Activity Area: Urban Design Protocol Case Study, Creating Places for People. http://www.urbandesign.gov.au/casestudies/geelong.aspx

- Vivoni, F. (2009). Spots of Spatial Desire Skateparks, Skateplazas, and Urban Politics. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 33, 130-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0193723509332580

- Vivoni, F. (2013). Waxing Ledges: Built Environments, Alternative Sustainability, and the Chicago Skateboarding Scene. Local Environment, 1-14.

- Weller, S. (2006). Skateboarding Alone? Making Social Capital Discourse Relevant to Teenagers’ Lives. Journal of Youth studies, 9, 557-574. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676260600805705

- Weston, P. (2010). Skate Parks a Haven for Drugs, Violence and Gangs in Southeast Queensland. Queensland: The Sunday Mail.

- Woolley, H. (2009). Every Child Matters in Public Open Spaces. Securing Respect: Behavioural Expectations and Anti-Social Behaviour in the UK (pp. 97-118). A. Millie. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Woolley, H., & Johns, R. (2001). Skateboarding: The City as a Playground. Journal of Urban Design, 6, 211-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13574800120057845