Open Access Library Journal

Vol.02 No.06(2015), Article ID:68477,11 pages

10.4236/oalib.1101634

The Art of Collaborative Autoethnography: Exploring the Evolution of a Self-Organizing, Non-Traditional Doctoral Cohort

Ashley Gleiman*, Davin Knolton, Kevin Mokhtarian

Department of Educational Leadership, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA

Email: *ashleygleiman@gmail.com

Copyright © 2015 by authors and OALib.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 23 June 2015; accepted 27 June 2015; published 30 June 2015

ABSTRACT

Using collaborative autoethnography methods, this article presents the exploration of three non- traditional doctoral student’s journey as they evolved into a self-organized cohort. Individual processes involving self-authorship, self-observation, personal reflections and analysis, combined with group dialogues and conversations about the experience lead to a formed sense of community amongst the researchers. Composite themes develop through a collaborative analysis of individual personal narratives highlighting significant learning experiences, adult development considerations, and the culturally adaptive nature of non-traditional doctoral students that often remain unexamined in other methodologies.

Keywords:

Collaborative Autoethnography, Self-Organizing Systems, Adult Development, Non-Traditional Doctoral Student

Subject Areas: Education

Today, doctoral students come from a variety of backgrounds and have distinct motivations for pursuing the objective of obtaining the elusive doctoral degree. Personal goals, as well as intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, remain complex entities and reasons for why some non-traditional doctoral students succeed over others. According to [1] , “The desire to learn, like every other human characteristic is not shared equally by everyone” (p. 3), which supports findings in our collaborative auto-ethnographic study of the doctoral cohort experience.

The traditional doctoral student attends graduate school for four years, acts as either a Graduate Research Assistant or Graduate Teaching Assistant, and often participates in ongoing faculty research and/or group projects leading to publication [2] . However, an increasing number of non-traditional students exist today that no longer meet the typical institutional standard of a doctoral student, yet continue to be expected to adhere to antiquated policies and procedures that no longer reflect the changing nature of adult students today. According to [2] non-traditional doctoral students are typically characterized by not being full-time students and are often “engaged in fulltime jobs, have family and social responsibilities, and participate in graduate study on a part-time basis or at a distance or both” (p. 1). Overall, we suggest that the one-size-fits-all doctoral program for the typical non-traditional student can be a hindrance for progress. Instead, the doctoral experience should be an individual and personalized endeavor.

An abundance of recent academic research surrounding the importance, strengths, and weaknesses of doctoral cohorts exists [2] - [11] . However, life circumstance and individual experiences can readily affect the outcome of a cohort experience. By general definition, cohorts are comprised of students pursuing the same field of education and take a majority of their class work together with a pre-determined schedule of classes. According to [8] , many higher education institutions now offer cohort models with the singular goal of increasing retention and graduation rates. This typical cohort model was not offered in our doctoral program experience, which initially met our individual needs in the beginning. Nevertheless, over two years ago we joined together as co-collabo- rators and students in an effort to form our own support system as non-traditional doctoral students. Personal changes as a result of the doctoral experience led to the discovery that we functioned better as a group than individual students. Along the way we discovered that our experiences were unique in comparison to other doctoral students in our program as we developed our own culture of challenge and support to motivate one another. Without intent, we became a self-organized cohort, which (due to group cohesion and reciprocity) functioned better and more successfully as opposed to our individual efforts.

Essentially, we were separate doctoral students that over time changed from unorganized to organized. While the “self-organized” term is most often used to describe biological systems such as bee hives, complex chemical reactions, and even brain functioning, the complexities of cohorts as social systems lends itself openly to interpretation and the examination of possibilities within a student’s development [12] . To say that our cohort is self- organized opens the door to interpretation and a contradiction on many levels. However, let us be clear in that we refer to ourselves as self-organizing with a simple and foundational definition where we as non-traditional doctoral students began as “individual systems” then through a series of “random events and positive feedback” we spontaneously connected as a group or “system” [13] (p. 125).

In recognizing the unique benefits of our self-organized cohort experiences we collectively decided to write an article recounting our experiences over time through autoethnographic practice. The original impetus for this project was an opportunity to explore our individual selves and the changes in our group development over time through the lived experience of completing a doctoral degree program. Thus, we begin with an overview of the literature and collaborative autoethnographic methodology used in this study, followed by individual narratives, which include our differing viewpoints, backgrounds, and perceptions. Next, we revisit the narratives via the lens of the literature to illustrate how the practice of autoethnography can build knowledge and provide new insight to existing theoretical frameworks used in this study. Finally, we provide implications for non-traditional doctoral students, educators of doctoral students, and a final overall reflection of the process.

1. Literature Review

In this study, systems theory and communities of practice provide the theoretical framework for our discussion. Systems theory is used frequently in academic literature to describe and explore the communicative behavior of dyads, specifically the behavior of individuals in face-to-face interaction [14] - [16] . Systems―whether they are physical systems such as tornados, or living systems with concepts of self, identity and consciousness―can emerge spontaneously and grow over time, as was the case with our particular cohort. We came together as distinct individual systems and formed yet another larger, more successful system over time. However, without an established sense of community our self-organized system would have otherwise failed. Therefore, the communities of practice concept, introduced by Lave and Wenger in the early 80’s, best describe the type of system we have become. According to [17] communities of practice are recognized as a type of system, fitting into the greater concept of systems theory. Wenger [18] offers this definition of a community of practice:

A community of practice can be viewed as a social learning system. Arising out of learning, it exhibits many characteristics of systems more generally; emergent structure, complex relationships… and self-or- ganization (p. 683).

Comparatively, [19] points out that communities of practice are not necessarily defined by characteristics like class of gender, nor simply by proximity, as in a work setting. Instead, “communities of practice… identifies a social grouping… [by] virtue of shared practice… one in which the course of regular joint activity develops ways of doing things, views, values, power relations, ways of talking” [19] (p. 1).

As individual learners we initially identified a common objective and together sought ways to accomplish our goals, which is indicative of a community of practice. If either our individual systems or ability to form as a group had failed, the possibility of a delay in meeting the objective or potential failure in the program would increase. Using this framework we asked ourselves, what occurred in our group formation that made it possible for us to successfully navigate our journeys as a non-traditional doctoral cohort?

2. Methodology

In this study we conducted a collaborative autoethnographic exploration of our experiences as non-traditional doctoral students self-organizing as a cohort between 2012 and 2014. Autoethnography is an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe personal experiences (auto) and systematically analyze (graphy) in order to understand cultural experiences (ethno) [20] - [22] . In the case of this study autoethnography is also a form of narrative inquiry further legitimatizing the personal stories and experiences we shared as we formed our own cohort within a community of doctoral learners. As a result, the concept of collaborative autoethnography ultimately defines this study as it is an intimate version of autoethnography where a group of researchers co-con- struct the culture and reality, which engenders “a sense of community amongst the researchers”… and where “…the process becomes as much of team-building activity as it is an approach to the production of knowledge” [23] (p. 58). The collaborative efforts we shared as researchers in this study became both the process and product of our own ensemble performance.

As collaborative researchers in this process the aim was to examine our differences and highlight a potentially productive experience as a cohort of non-traditional doctoral students. To generate data, we each maintained and constructed a detailed written account of our personal journey as non-traditional doctoral students from 2012- 2014. These accounts included personal narratives; self-generated recollections of critical discourse over the course of eight months carpooling back and forth to campus for classes; and regular meetings to discuss progress, successes, and personal failures as they related to the doctoral student experience. Throughout this process we maintained regular face-to-face meetings and email exchanges during which we brainstormed ideas about incidents that had been critical to us in terms of our dissertation progress. These meetings and exchanges also included discussion regarding our work and personal lives. Overall, this method enabled a process of critical discourse and “collaborative introspection” through our conversations as we told our own stories and responded to each other’s interpretation of the events [24] (p. 92).

Upon completion we individually reviewed and analyzed each narrative account separately. In our small group we discovered common themes throughout the narratives. Figure 1 illustrates a detailed overview of the collaborative process in this study.

3. Personal Narrative

3.1. Context

In order to fully understand the phenomenon of doctoral completion success, one must first begin by understanding the nature, the beliefs, and the actions of those who navigate the complex demands of adult life and doctoral studies. In the field of adult education, self-authorship enables both the individual and those around them the opportunity to examine such differences from a personal perspective. According to [25] , the concept of self-authorship captures many elements of maturity in adulthood, to include reflective and critical thinking, which can be key characteristics in successful doctoral students. Self-authorship, or the capacity to coordinate external influence to internally define one’s beliefs, identity, and social relations, enables us to navigate life’s challenges more effectively [25] . In fact, the very practice of self-authorship promotes personal autonomy, helps one make sense of the experience, and highlights shared experiences, which can further enhance the delicate balance found in doctoral cohort relationships. Thus, our stories highlight the challenges each of us experienced on our journey as a self-organized cohort.

Figure 1. Process of collaborative autoethnography. Adapted with permission from Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F.W., Hernandez, K.C. (2013). Collaborative autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc.

3.2. Ashley’s Narrative

As a girl from rural Alabama, the idea of a doctoral degree never crossed my mind until it was staring me in the face. Admittedly, I still sometimes wonder why I chose to do this (pursue a PhD). This question continued to plague my thoughts over the last few years as I moved through my studies. I knew a doctoral degree wouldn’t necessarily increase my salary or earnings potential as a 30-something career professional. I could enjoy doing many different occupations, but would I really need a PhD to enjoy what I do? Sure, the title would be cool, but then again was I in it for the cool factor? These are not new or groundbreaking thoughts, by any means. I knew that. Perhaps it was my competitive nature or the thought that I could accomplish something significant in my life that was just for me. After 10 years of being a military spouse and mother to two young children, I admit I lost part of my identity and saw a degree as a way of reclaiming myself. The idea that a doctoral degree would be for me and not necessarily for my kids or my husband was something new to get excited about in my life.

Over the years I came to love the idea of learning as it fulfilled natural curiosity and provided a way to better understand things and people in my world. Thankfully, being a military spouse and living a military lifestyle helped to foster that love of learning and consequently opened many doors for me, which is how I found a career in higher education and a research topic that allowed me to give back to my military community. When it came time to begin my doctoral program I knew for sure that it would be personalized and fit my way of learning, which is often self-directed. However, I did not realize or understand the significant impact the relationships I would make with my fellow doctoral students and how those connections would affect me over time.

The concept of a cohort at first was not appealing as I entered the doctoral program. However, completing the process and being part of a group during the final phase, I became incredibly dependent upon one. Over time I knew both Van and Kevin at different phases throughout the process, however it wasn’t until the last few classes that we came together and found a common bond for completion. With three different major professors, topics, and backgrounds the only thing we shared in common was our personal need and motivation for completing the degree. We shared stories, laughter, a difference in opinions, and a great deal of respect for one another over time, which fostered the development of our doctoral personal cohort. We call ourselves a system as a result of this process, because over time we realized that we functioned better as a group than we did individually.

As I write this I realize in hindsight that completing the coursework was not nearly as challenging as the actual process of writing the dissertation. Classes provide a timeline for which to complete the work, but writing the actual dissertation became one of the most difficult experiences of my life. Could I have completed this process on my own? Yes, I believe I could have. Would my experience as a doctoral student been nearly as rich and meaningful without our self-organized cohort? Absolutely not.

3.3. Van’s Narrative

In my early years of higher education the thought of a doctoral degree did not even play in my mind. I was a simple country boy who wanted to be a soldier. In fact, just before graduating high school I attended a field trip to the local state university. The guidance counselor chided me that the trip was only for those students who had an interest in actually attending a university. I knew that I needed a bachelor degree (any degree) to become an officer so I attended the trip to find my educational path of escape to the army. I completed my bachelor degree for a specific purpose and one of my main personality traits is that I am very outcome or task oriented.

As I matured in my career I continued my non-military education and completed my master’s degree to make myself more competitive for promotion. Although my father-in-law had a doctoral degree, the thought of me progressing to that level still did not enter my thought process; it just was not needed for progression or promotion within my chosen profession. However, one trait I acquired throughout my career is that of continual learning, in fact I had now been in “school” for over 20 years. I found that I enjoyed learning and that I enjoyed teaching others. After retirement from the military I wanted to challenge myself with a goal that is just for me… one that is not needed for career or “looks good on a resume”.

I entered the doctoral program as a non-traditional student and found myself constantly negotiating multiple identities of being a student, father, full-time worker, and a veteran army officer. I was experiencing my first disorienting dilemma; I was as old as or older than many of my professors, older than many of my fellow doctoral students, and significantly older than most students on main campus.

After the first block of required master’s level coursework, my “cohort” went multiple directions and I had to find another support system. During the coursework I found (and was found by) the other members of our self-organizing cohort. Our cohort was built upon our selection of each other and not random assignment from an admin office, entrance date, or common major professor. We began having regular meetings between classes and discussed material; each having a separate voice that was heard, considered, and expounded upon. I not only was able to experience reflective learning, but as we each voiced our understanding I was able to truly engage in a discourse I had not taken full advantage of in the normal classroom, providing me with a much richer and deeper understanding that helped me make meaning and reinforced my premise of “doing this for me”.

We all learn in different ways and at different speeds. Our system helped me to learn and apply new knowledge and new meaning in a safe atmosphere. My cohort did not judge me, I was not competing with them, and I was there to help them as much as they helped me. The system enabled a feedback loop that I was unable to achieve on my own. During the drive to and from class, at the library, the sandwich shop, or at the speed of an e-mail or text, the “system” responded with encouragement, support, and a shared experience that bonds people together. Our system is formed from different backgrounds, ages, and experience but forged in mutual trust and confidence we have grown over time to become a single system that responds to the needs of the other parts for the good of the system.

3.4. Kevin’s Narrative

I was the very definition of the non-traditional learner. I transitioned from a traditional college career into work life without earning a degree. Several years later I understood that I would not develop a career without a degree and I returned to college to complete a bachelor’s degree. Soon after I found myself on a career path and a master’s degree became an important mechanism for moving my career forward. I was involved in corporate training and development and a degree in adult and continuing education would make me more marketable and more effective in my work. At the same time, I was also gaining a new appreciation for learning.

The master’s program was a great experience and opened up new horizons in the field of adult education. In fact, it became, for me, the disorienting dilemma referred to in the work of Jack Mezirow and others. The courses and instructors were extraordinary; however, each class often involved new students and varied settings. While I was experiencing a re-orientation of my belief system, an important component was missing.

Through my research I realized I was not experiencing critical discourse and critical reflection. I deeply considered the coursework and the content―and the experience of others―but there was no mechanism to complete the transformation and move to a new level of development and achievement. Enter the doctoral program and my friends became a new set of “systems” that would soon organize to create something greater.

What the “system” did for me was to allow me to experience the discourse and reflection that had been missing previously. In concert with my peers, I was able to process what I had learned in my master’s program (and beyond) and to form conclusions about what I believed and how I was changed by the experience. As a result, the work in my doctoral program took on deeper meaning and my motivation moved from slightly career-fo- cused to something more intrinsic and self-fulfilling. The decision to earn a doctorate was, in fact, much less about career and more about learning and growing. It solidified my desire and the decision to make the transition into higher education.

We each will earn our degree in the specialty we have selected. Our topics are unrelated except for their focus on adult learning and development. However, the outcome of our program will be greater than a degree. Being part of a system contributed to deeper learning and meaning making for me, and I believe, for the others. We were able to look at motivation, design, and process in a way that can be shared with others to assist them through their educational journey without losing their individuality. As a result, we discovered process improvements and offered critical feedback to our advisors and program administrators. Ultimately, we will graduate with more knowledge than what we could have achieved through the coursework and research alone.

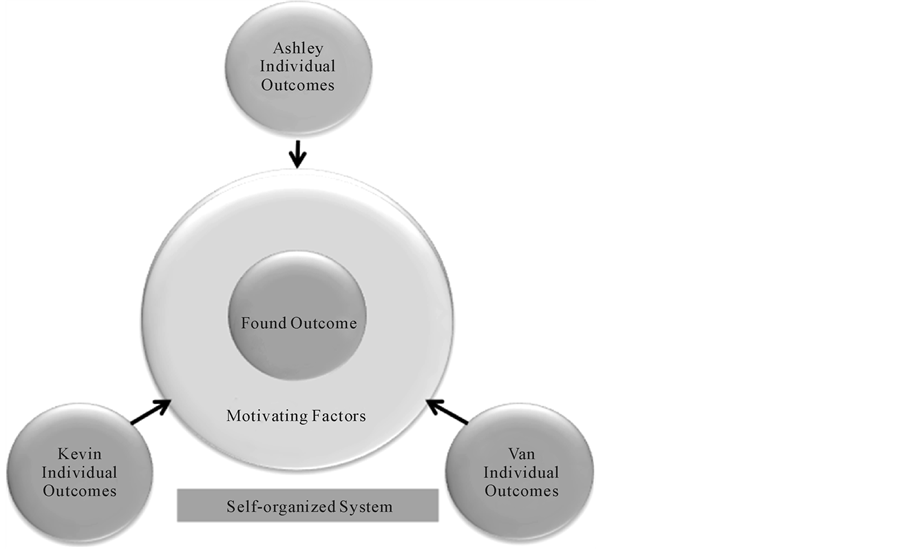

As non-traditional doctoral students our backgrounds, ages, and life experiences vary greatly. Additionally, we all have deeply personal reasons for why we chose to pursue a doctoral degree and consequently differing outcomes in what we want to do after obtaining the degree. Furthermore, we each maintained different major professors and committee members throughout this process. Therefore our collective experiences reflect a truly unique perspective of students coming together for a greater purpose. Figure 2 provides a found structure diagram highlighting how individual goals systemically organized into shared goals and outcomes despite our personal and professional differences.

4. Connecting Reflections to the Literature

The data for this study came through personal narratives and reflection, in combination with scholarly research on self-organizing systems. There was no coding per se, of the data. Instead, we discovered three common themes found throughout the narratives: background, motivation, and meaning making.

The first theme, or common factor, stems from our varied backgrounds. It’s clear from the narratives that we had different backgrounds and grew up in fairly distinct circumstances. To be fair, we are all white, middle-class

Figure 2. Found structure diagram of self-organized system.

individuals. When it came to higher education, we initially pursued college as a trajectory in our individual career aspirations and did not envision or anticipate seeking a doctoral degree. The commonalities in our backgrounds reveals an occurrence in perspective transformation as we each experienced a challenge to the status quo that pushed us to make the significant decision to pursue a doctorate. For example, as a military spouse Ashley never thought she would be in one location long enough, nor have enough time and energy to pursue her doctorate:

Over the years I’ve seen hardships and triumphs as a military spouse, but most of those moments were for my husband, my children, and/or soldiers in my husband’s military unit. For once I saw an opportunity to pursue something for myself, which is one of the reasons why I decided to continue my academic pursuit in the doctoral program.

Comparatively, Kevin and Van experienced something similar, which ultimately leads to motivational factors. For Van, it was a long-ago life’s lesson about pursuing an education. While application of this lesson may have been delayed, it became satisfying and motivating as he moved through his master’s degree and into the doctoral program.

The second common theme related to intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors found in all three narratives. According to [26] , intrinsic motivation moves an individual to act for satisfaction, enjoyment, or personal challenge, while extrinsic motivation propels action because it is externally prompted and valued by others to whom one is connected. Initially, all three of us began the doctoral program with specific goals and motivations, as the idea of life-long learning was inherently interesting and enjoyable. Over time, those motivations evolved into something deeper and richer because of the cohort experience. For example, Kevin stated,

I was surprised at the sustaining power of being intrinsically motivated. It is a much stronger form of motivation than external factors and in my mind hints at Kegan’s levels of development. Finding two others who shared this experience was exciting and only added to my desire to learn more and complete my degree.

In reviewing these motivations the completion of our master degree programs led to a reexamination of the need and ultimately reasons for participating in additional education. Thus, it was a catalyst that caused the action of seeking a doctoral degree. However, desiring something for our “selves” with no certainty that the degree would pay-off is a conclusion we each reached on our own. The fact that we shared that factor came to light only after the cohort became organized.

The third theme has two components: Meaning making as both individuals and as a group. In one respect, the adult learning concept of self-directedness is alive and well in our cohort. We each were looking for greater meaning from the course content when we discovered one-another and formed into a self-sustaining group. As we began to reflect on course content and our research topics, we “took the learning deeper” and the material took on new meaning. We pushed this concept further, however, as we became self-aware as a cohort. Half way through our experience as a new cohort, we began to recognize something special was happening to us, something we did not see happening to―or occurring within―other doctoral students in the same program. After a monthly doctoral student meeting within the program, Van noted how other students did not seem to be progressing as quickly or with as much success as our self-organized cohort:

As I sat around the room faced with doctoral students that finished coursework well before me, I realized how much further along we were in our progress than many of our peers. I realized how important this cohort of support of ours was in motivating me to get to this point. We did not exclude others, we tried to bring others into the mix, but for one reason or another it never happened for them.

This self-awareness opened the door to a new line of questioning and reflection as we sought to understand how and why our system had organized and what it meant to our overall doctoral program experience.

Ideally, we wrote our narratives to clarify and understand the transformation of three individuals into a single group identity. Our group pushed us to greater heights together than we believe we would have achieved individually had our group not formed. This is a good demonstration of our individual and group development over time. Kevin stated,

The system allowed me to experience the discourse and reflection that I had been missing. With Van and Ashley, the long commute in the car enabled me to process and to form conclusions about the curriculum and what I believed and how I was changed by the experience, resulting in something more intrinsic and self-fulfilling.

The regular critical discourse we experienced during carpool rides to and from campus pushed us to new heights of understanding and even more towards questioning and internal reflection of the material. During the carpool each week our group had the opportunity to engage in a much more meaningful critical discourse and reinforced the group relationship we had achieved. Over the weeks it became apparent that in the carpool you had to be at the top of your game [thought process] as we challenged each other with the week’s reading assignments. During the classroom discussion it was often noted (and once remarked by the instructor) that our understanding and practical application of the material was above that expected during classroom instruction. Essentially, it paid to be in the carpool. According to [27] , “environments that support perceptions of social relatedness improve motivation, thereby positively influencing learning behavior” (p. 853). Overall, our cohort functioned initially to support one another and soon formed concrete group goals. However, each person discovered that as we pushed the others, our own objectives were also realized. The objectives of cohort involvement described by [27] “…to improve students’ critical thinking skills, overall learning, and ability to work in teams; to facilitate better integration of content across the curriculum; and to enhance student retention” (p. 854) came to fruition. (We observed students dropping courses. These students did not express an interest in nor an affiliation with any sub-group or unique cohort.) In addition, through a series of random events our self-orga- nized system evolved over time. These events included two professional association presentations as well as an article describing our experience.

As we attempted to include other doctoral students in the cohort, we discovered there were distinct differences in motivation and how each person approached the need for support. Among the majority of the students, support was interpreted as something to be received (being “pushed”) but not as a responsibility to provide this same support to peers. In fact, the support was expected to come via a traditional learning format; the instructor provided feedback and guidance and the students applied the feedback to achieve the course objective. Several direct comments from classmates included the desire to “simply finish” and there was very little interest in connecting content from one course with ideas from other courses in the program. For these students, the program appeared to be much more a series of individual events and activities and much less a cumulative learning experience.

One might ask, what kind of system is our cohort? Are we even truly a system? It may be argued that we are not a system but perhaps a cooperative. After all, each of us operates as an independent system, accepting input, consuming resources, and creating output. In practical terms we do not need one another to accomplish the objective of earning a doctoral degree. To be considered a system, our coming together would imply that each of us brings a portion of the overall mechanism that combines with the others to form a new system. Our output must be either greater than or different from what we can achieve individually. For Van, this was a significant outcome of being part of a cohort towards the end of the doctoral program:

Individually, I found myself capable of achieving the program requirements and succeeding. As an individual, I was producing to my perceived capacity, however with the addition of my cohort the system pushed me to even higher self-achievement for the group’s expectations. The group helped me push and stretch myself farther to not hold the others back and achieve more out of the program than I would have individually.

In reflection of the process we believe we are a system. In our narratives we describe the sense of trust that helped spawn our cohort. In addition, we recognized the opportunity to examine topics more deeply and achieve a higher level of cognition through working together. According to Kevin, “transformative learning cannot occur in a vacuum. It is reliant on a safe environment and the shared experience with others. The new-found objectives are a distinctive of communities of practice.” These facets bind us together and support the communities of practice concept, which “is well aligned with the perspective of the systems tradition”… and can be viewed as a simple social system” [28] (p. 1). Additionally, [29] suggests “that cohorts of adult learners, grouped in the context of their companies and communities will provide more value to the individual student and their community” (p. 1). Our cohort does not share a company, but does share at least two communities and subsequent cultural identities. One is the field of Adult and Continuing Education, which we feel a part and through which we contribute to the learning of others within the community. The other is the new community formed by our cohort, one designed to facilitate movement toward the achievement of a doctoral degree.

5. Implications

The needs of non-traditional doctoral students (such as ourselves) continues to evolve as most are interested in finding programs that fit their academic, personal, and professional needs in a changing global environment. In response to this growing market of learners, many institutions of higher education attempt to parallel the increased needs of non-traditional students by offering doctoral programs that “combine academic rigor and applied knowledge, scholarship, convenience, and flexibility” [2] (p. 3). As progress continues and the development of new non-traditional specific doctoral programs emerge, more evidence surrounding the individual experience and needs of non-traditional doctoral students continues to exist. While our collaborative auto-ethno- graphic process initially served as an opportunity to explore our individual experiences and changes within our group development overtime, the end result promotes awareness and further understanding of group dynamics for institutions looking to change or develop new programs.

As a group we each identified a need for support as we progressed through our individual plans and thus self-organized as a cohort to address our learning needs and mitigate the outward effects of being non-traditional (distance) learners within a traditional institution. According to [27] , cohorts should provide students with a sense of academic relatedness and help foster students “ability to work with others in solving complex, job-re- lated problems” (p. 870). Given the complexities of doctoral work, full-time careers, and family obligations, cohorts can form considerably tight bonds and social support networks in order to cope with the demands of juggling expectations and workloads. Within these networks, the concept of social capital within a community of practice has significant utility for educators in describing the informal relationships and their complex dynamics. Managing and accumulating social capital within non-traditional doctoral communities helps to describe the challenge of people seeking influence and support within and from these networks. These challenges stem from the idea that the successful accumulation of social capital depends on a “the norm of reciprocity”, or quid pro quo, which is often found in support networks [30] (p. 815). Others, including [31] , fundamentally support Furstenberg’s perspective of social capital as they explain that some social support networks combine both “generalized reciprocity” and “communitarian character”, which reflects the balance of “give and take” in most relationships (p. 210). Therefore, the strength of such non-traditional doctoral student support networks may very well rely on the altruistic behavior of individuals who act on the understanding that they may someday receive support in return from someone with whom they are not personally acquainted [31] .

Overall, engagement within our cohort allowed us to collaborate with each other as adult learners and form a collaborative group that focused both on the construction of content knowledge and achieving our goals of earning a PhD. Essentially, our autoethnographic process illustrates how non-traditional doctoral students can socially construct their experiences through self-organization, persistence, and group success in a doctoral program. Thus, providing insight to program developers and institutions of higher education looking to meet the specific needs of a growing population of non-traditional doctoral students.

6. Final Reflections

In summary, we chose to employ a collaborative autoethnographic methodology to describe and systematically analyze our personal experience in order to critically reflect upon and to understand our experience. Our collaborative autoethnographic practice involved several layers of reflection and self-discovery. We started with our own individual narratives on the topic of our perceived experiences over the past two years through the completion of our doctoral programs. Through our research we discovered three common themes: each of us initially pursued a college education for career purposes and did not envision or anticipate seeking a doctoral degree, yet each of us had developed the common trait of being a life-long learner; a desire to achieve something just for ourselves; and the application of the concept of self-directedness that enhanced us individually and was magnified within our group identity.

[32] describe culture as any group of people who associate with one another on the basis of some common purpose. Furthermore the purpose and frequency the system meets the culture that develops is most often a critical factor to the educational environment and an important part of many members’ personal lives.

Ultimately, are we more successful because we worked together through this process? So far we believe that our successes are self-evident, but only once we reach 100% dissertation completion amongst the three of us can we say that we have been truly successful in our endeavors. The final objective may not be known here because it has the potential to develop into that next idea or project―a second article or collaborative project, if you will. While we contrived our own measures of success, this collaborative autoethnographic experience was not without its challenges. In this study all three authors contributed equally to the collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, and writing of the article. This truly collaborative effort presented challenges that took a great deal of time, patience, and consensus in order to complete. For example, when reviewing the narratives we attempted to do so individually and then again as a group. During this group process there was a greater potential for one member of the group to be unduly influenced by the voices or one or more assertive team members. Generally, in an effort to mitigate these challenges we continued our work together until arriving at consensus acceptable to each of us.

Overall, we realize our experiences are not unique. However, our goal was to explore our individual and collective experiences and share a combined perspective of the process with others. Negotiating through this collaborative autoethnographic experience has enabled each of us to grow beyond our original individual intent and create a much richer and deeper meaning leading us to the level of success we enjoy so far. As we continue to progress and grow, helping each other to the final graduation line where we assume the mantle of doctor, our system will continue providing us support to collectively assist others along their journey.

Cite this paper

Ashley Gleiman,Davin Knolton,Kevin Mokhtarian, (2015) The Art of Collaborative Autoethnography: Exploring the Evolution of a Self-Organizing, Non-Traditional Doctoral Cohort. Open Access Library Journal,02,1-11. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1101634

References

- 1. Houle, C.O. (1961, 1988, 1993) The Inquiring Mind. Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education, Norman.

- 2. Pappas, J.P. and Jerman, J. (2011) Topics for Current and Future Consideration. In: Pappas, J.P. and Jerman, J., Eds., Meeting Adult Learner Needs through the Nontraditional Doctoral Degree, New Directions for the Adult and Continuing Education, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 129.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ace.404 - 3. Barnett, B.G., Basom, M.R., Yerkes, D.M. and Norris, C.J. (2000) Cohorts in Educational Leadership Programs: Benefits, Difficulties, and the Potential for developing School Leaders. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36, 255-282.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0013161X00362005 - 4. Brown, C.J. (2011) Learning Communities or Support Groups: The Use of Student Cohorts in Doctoral Educational Leadership Programs. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database, Order No. 3453645.

- 5. Fitzpatrick, J.A. (2013) Doctoral Student Persistence in Non-Traditional Cohort Programs: Examining Educationally Related Peer Relationships, Students’ Understanding of Faculty Expectations, and Student Characteristics. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database, Order No. 3594664.

- 6. Hildebrandt, D.M. (2011) The Perceived Impact of Social Network Sites on Online Doctoral Students’ Sense of Belonging ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database, Order No. 3453112.

- 7. Lange, N.D., Pillay, G. and Chikoko, V. (2011) Doctoral Learning: A Case for a Cohort Model of Supervision and Support. South African Journal of Education, 31, 15-30.

- 8. Lei, S., Gorelick, D., Short, K., Smallwood, L. and Wright-Porter, K. (2011) Academic Cohorts: Benefits and Drawbacks of Being a Member of a Community of Learners. Education, 131, 497-504.

- 9. Mullen, C.A. and Tuten, E.M. (2010) Doctoral Cohort Mentoring Interdependence, Collaborative Learning, and Cultural Change. Scholar-Practitioner Quarterly, 4, 11-32.

- 10. Santicola, L.L. (2011) Characteristics and Motivations That Led to Persistence in Doctoral Cohort Study. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database, Order No. 3528370.

- 11. Zahl, S.B. (2013) The Role of Community for Part-Time Doctoral Students: Exploring How Relationships Support Student Persistence. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database, No. 3587513.

- 12. Sinnott, J.D. and Berlanstein, D. (2006) The Importance of Feeling Whole: Learning to “Feel Connected”, Community, and Adult Development. In: Hoare, C., Ed., Handbook of Adult Development and Learning, Oxford University Press, New York.

- 13. Ashby, W.R. (1947) Principles of the Self-Organizing Dynamic System. Journal of General Psychology, 37, 125-128.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1947.9918144 - 14. Fogel, A. (1992) Movement and Communication in Human Infancy: The Social Dynamics of Development. Human Movement Science, 11, 387-423.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-9457(92)90021-3 - 15. Fogel, A. (1992) Co-Regulation, Perception and Action. Human Movement Science, 11, 505-523.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-9457(92)90031-6 - 16. Magai, C. and Haviland-Jones, J. (2002) The Hidden Genius of Emotion: Lifespan Transformations of Personality. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511509575 - 17. Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355 - 18. Wenger, E. (2010) Communities if Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of a Concept. In: Blackmore, C. Ed., Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, Springer-Verlag, London.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_11 - 19. Eckert, P. (2006) Communities of Practice. In: Brown, K., Ed., Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, 2nd Edition, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 683-685.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/01276-1 - 20. Ellis, C. (2004) The Ethnography I: A Methodological Novel about Auto Ethnography. AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek.

- 21. Holman-Jones, S. (2005) Auto Ethnography: Making the Personal Political. In: Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S., Eds., Handbook of Qualitative Research, Sage, Thousand Oaks, 763-791.

- 22. Ellis, C. Adams, T.E. and Bochner, A.P. (2011) Auto Ethnography: An Overview. Historical Social Research, 36, 273-290.

- 23. Toyosaki, S., Pensoneau-Conway, S.L., Wendt, N.A. and Leathers, K. (2009) Community Autoethnography: Compiling the Personal and Resituating Whiteness. Cultural Studies, Critical Methologies, 9, 56-83.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1532708608321498 - 24. Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F.W. and Hernandez, K.C. (2013) Collaborative Autoethnography. Left Coast Press, Inc., Walnut Creek.

- 25. Baxter Magolda, M. (2007) Self-Authorship: The Foundation for Twenty-First Century Education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 109, 69-83.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.266 - 26. Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L. (2000) Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020 - 27. Beachboard, M.R., Beachboard, J.C., Wenling, L. and Adkison, S.R. (2011) Cohorts and Relatedness: Self-Determination Theory as an Explanation of How Learning Communities Affect Educational Outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 52, 853-874.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11162-011-9221-8 - 28. Smith, M.K. (2003, 2009) Jean Lave, Etienne Wenger and Communities if Practice. The Encyclopedia of Informal Education.

www.infed.org/biblio.communities_of_practice.htm - 29. Stocker, G. (2013, September) Using a Cohort Learning Model to Improve Learning in Companies and Communities. Proceedings of the 32nd Research-to-Practice (R2P) Conference in Adult and Higher Education, St. Charles, 20-21 September 2013, 20-21.

- 30. Furstenberg, F.F. (2005) Banking on Families: How Families Generate and Distribute Social Capital. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 809-821.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00177.x - 31. Moelker, R. and Van Der Kloet, I. (2003) Military Families and the Armed Forces: A Two-Sided Affair? In: Caforio, G., Ed., The Handbook of the Sociology of the Military (201-224), Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, 201-224.

- 32. McCarthy, J., Trenga, M.E. and Weiner, B. (2005) The Cohort Model with Graduate Student Learners Faculty-Student Perspectives. Adult Learning, 16, 22-25.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.