Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.4, 291-299 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.24046 Adolescents’ Subtypes of Attachment Security with Fathers and Mothers and Self-Perceptions of Socioemotional Adjustment Michal Al-Yagon School of Education Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel. Email: alyagon@post.tau.ac.il, alyagon@bezeqint.net Received February 22nd, 2011; revised April 3rd, 2011; accepted May 13th, 2011. The study examined adolescents’ secure attachment with both versus one parent, for deeper understanding of adolescents’ perceptions of their socioemotional adjustment. Specifically, the current study aimed to identify different attachment profiles with father and mother among 203 adolescents aged 15 - 17 years and to examine whether these profiles associated differently with their self-rated peer-network loneliness and peer-dyadic lone- liness, positive and negative affect, and internalizing behavior problems. Descriptive statistics demonstrated that more adolescents were classified as securely attached to mothers than to fathers. No significant associations emerged between adolescents’ sex and attachment classification distributions with mothers or fathers. Using k-means clustering methods, four distinct clusters emerged: secure attachment to both parents/to neither/to only father/to only mother. Tukey HSD and Scheffe procedures validated the attachment clusters, revealing signifi- cant inter-cluster differences on all of the adolescents’ socioemotional measures. The current results also high- lighted that the group of adolescents who felt securely attached to both parents was least vulnerable to experi- encing socioemotional difficulties. In addition, secure attachment only to one’s mother and not to one’s father did not seem to act as a protective factor for these adolescents, with the exception of protection from peer-dyadic loneliness. Discussion focused on understanding the possible contribution of parent-adolescent secure attach- ment among these subgroups of typically developing adolescents. Keywords: Attachment, Fathers, Socioemotional, Behavior Problems, Affect Research studies on the adolescent developmental period have indicated a sharp increase in vulnerability, morbidity, and mortality related to a wide range of emotional, social, and be- havioral problems (Dahl, 2004; Lee & Hankin, 2009; Muris, Meesters, & Van den Berg, 2003). Data from these studies revealed an inverted U-shape curve depicting adolescents’ ex- ternalizing problems (e.g., aggression and delinquency), with prevalence peaking during the middle adolescent years and then declining (Lee & Hankin, 2009; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Conversely, the prevalence rate for internalizing problems (e.g., depression, anxiety) showed an increase during adolescence that continued into adulthood (Lee & Hankin, 2009; Steinbeg & Morris, 2001). In exploring this marked increase in socioemo- tional difficulties, various theoretical approaches emphasized variables such as hormonal changes at puberty, the emergence of new cognitive abilities and coping mechanisms, the preva- lence and nature of stressful life events, and the quality of close relationships and patterns of attachment with significant others (Dahl, 2004; Jackson & Goossens, 2006; Larson, 2000; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Based on studies emphasizing attachment theory as a highly relevant and well-validated framework for explaining individ- ual variations in adjustment across the lifespan (Grossmann, Grossmann, & Waters, 2006; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007), adolescents’ attachment to mothers and fathers served as the focus of the current study to examine socioemotional adjust- ment during the adolescent period. Adolescent-father attach- ment relationships received equal emphasis in the present study in light of the recent upsurge of interest in fathers’ important role for their children’s development and later adjustment (Marsiglio, Amato, Day, & Lamb, 2000; Parke, 2004), as well as based on findings highlighting possible differences in younger children’s attachments to the mother and father (see Grossmann et al.’s 2002 review). Adolescents’ Attachment Relationships with Father and Mother Briefly, attachment theory pinpoints the role of social inter- actions in socioemotional and behavioral development (Bowlby, 1973, 1982/1969). In their first year, infants develop specific and enduring relationships with primary caretakers (Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969; Bowlby, 1973, 1982/1969). Their strong pur- suit of proximity to caregivers is the overt manifestation of the attachment behavioral system—an inborn system designed to restore or maintain proximity to supportive others in times of need. Bowlby (1973) assumed that infants internalize their interactions with significant others into “internal working mod- els”—mental representations of significant others and the self. These result in unique attachment styles, that is, stable patterns of cognitions and behaviors that become manifested in later interpersonal close relationships as well as in intrapersonal organization. Thus, many studies suggested the links between children’s attachment style and socioemotional adjustment, indicating that securely attached children show greater emo- tional regulation, sociability, and psychological well-being than children with an insecure avoidant or anxious style (see Grossmann et al.’s 2006 review). Attachment relationships continue to influence interpersonal and psychosocial functioning beyond early and middle child- hood (Engels, Finkenauer, Dkovic’, & Meeus, 2001; Mayseless  M. AL-YAGON 292 & Scharf, 2007). Adolescents’ attachment behaviors emerge in different ways compared to earlier ages, such as more explor- ative behaviors and less dependency on parents; however, re- search studies clearly show the substantial associations between adolescents’ attachment organization and various adjustment and maladjustment measures such as depression, anxiety, be- havior problems, and self-esteem (Irons & Gilbert, 2005; Lee & Hankin, 2009; Muris et al., 2003; Song, Thompson, & Ferrer, 2009). Furthermore, studies have also highlighted that adoles- cents’ developmental tasks such as autonomy and exploration are easily established in the context of close, enduring relation- ships with parents (Allen & Land, 1999; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Adolescents’ patterns of attachment with fathers have been less studied, but the existing research regarding the role of fa- ther-child attachment relationships for younger children’s func- tioning has yielded inconsistent findings. For example, mixed results emerged regarding the link between secure attachment with fathers and children’s positive interactions with peers in middle childhood (see Parke et al., 2004 for a review). Grossman et al. (2002) noted that children’s attachment rela- tions with father and mother derive from different sets of early social experiences. Mothers often act as a secure base in times of distress; fathers often act as a challenging but reassuring play partner. Several studies on middle childhood supported these assumptions and also pinpointed the unique role of children’s attachment to their fathers (Lamb, 2002; Lieberman, Doyle & Markiewicz, 1999; Verschueren & Marcoen, 2005). As re- ported by Verschueren and Marcoen (2005), secure attachment with the mother may best predict a child’s functioning in inti- mate small groups or dyadic interactions, whereas secure at- tachment with the father may best predict peer acceptance in the larger social network. Further, research on sex differences in attachment patterns also revealed inconsistent findings calling for further investiga- tion. On the one hand, attachment theory argued that attach- ment relations do not vary as a function of children’s sex (Bowlby, 1973, 1982/1969). Similarly, studies among adults revealed no consistent sex differences using either interviews (i.e., Adult Attachment Interview) or self-report questionnaires (see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007 for a review). On the other hand, research reported that father-daughter relations may change considerably in early adolescence, becoming emotion- ally distant and flat (see Lieberman et al., 1999 for a review). Together, these findings raise important questions calling for exploration. Do adolescents hold constructed separate repre- sentations of their attachment relationships with each parent or one overall generalized representation? Will sex differences emerge in these adolescents' relationship patterns? Will adoles- cents classified as securely attached to both parents manifest fewer socioemotional difficulties compared to adolescents clas- sified as securely attached to only one parent? How might these different profiles associate with adolescents’ socioemotional and behavioral measures? Who among these different profiles might be more vulnerable to socioemotional problems? Adolescents’ So c i oemoti onal Adjustment The present examination of adolescents’ socioemotional ad- justment included three socioemotional and behavioral aspects: positive/negative affect, peer-network or peer-dyadic loneliness, and the internalizing behavior syndrome. Affect. Affect is considered to hold unique importance for understanding individuals’ mental health and well-being (Clark & Watson, 1988; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). Research studies demonstrated that over the transition from childhood to adolescence, individuals experience an increase in negative emotions, a reduction in positive emotions, and greater emo- tional lability (Irons & Gilbert, 2005; Larson, 2000; Lee & Hankin, 2009). Empirical data have also pinpointed links be- tween adolescents’ frequency of negative emotions and their externalizing and internalizing behavior problems (Goossens, 2006; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003). Loneliness. Loneliness refers to unpleasant experiences oc- curring when individuals perceive a discrepancy between their desired and achieved patterns of social networks (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). This measure may be considered as a global indicator of one’s dissatisfaction from the quality and/or the quantity of one’s social interrelations (Asher, Parkhurst, Hymel, & Williams, 1990). Feelings of loneliness are perceived by the attachment framework as a form of separation distress that stems from a failure to meet basic attachment needs (Weiss, 1973). Previous research reported an association between chil- dren’s high levels of loneliness and a variety of unpleasant emotions and perceptions of unfulfilled relational needs such as a lack of support, companionship, and affection (Asher & Paquette, 2003; Asher et al., 1990). Similarly, large numbers of studies also indicated that feelings of loneliness in childhood are associated with later maladjustment problems such as de- pression, suicide, poor self-concept, and psychosomatic prob- lems (Chen et al., 2004; Hoza, Bukowski, & Beery, 2000; Richaud de Minzi, 2006). Of particular importance is the broad agreement that the loneliness experience is particularly prevalent in the adolescent developmental period (see Goossens, 2006 for a review). For example, Brennan (1982) found that high percentages of ado- lescents, ages 12 to 18 years, reported high levels of loneliness. Moreover, adolescents at 17 years of age reported higher levels of loneliness than college students at age 19 (Mahon, 1983; Schults & Moor, 1988). Data from previous studies also pin- pointed a decreasing age trend in adolescents’ loneliness, where early adolescents (13 years) showed higher loneliness levels than mid-to-late adolescents (age 15 and 20 years). Internalizing behavior problems. Research has suggested that maladaptive functioning in childhood and adolescence falls into two categories of disorders: internalizing and externalizing (Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach & Dumenci, 2001). The current study focused only on adolescents’ perceptions of their inter- nalizing behavior problems like depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal, which were shown to increase in prevalence during adolescence and continue to increase into adulthood (Lee & Hankin, 2009; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Externalizing mal- adjustment, which includes hyperactivity, aggression, and anti- social disorders, is beyond the scope of this study. The Current Study This study aimed to further explore the links between ado- lescents’ attachment relationships with both parents versus one parent and adolescents’ perceptions of three socioemotional adjustment measures: affect, loneliness, and internalizing be-  M. AL-YAGON 293 havior problems. Specifically, this study aimed to identify sub- groups of adolescents in the 10th and 11th grades with different individual profiles of attachment classifications with father and mother and both parents, and to examine the possible role of these patterns of close relationships for explaining adolescents' socioemotional characteristics, hypothesizing: 1) Four profiles of adolescents’ attachment classifications were expected: secure attachment to both parents, insecure attachment to both parents, secure attachment to father and insecure attachment to mother, and secure attachment to mother and insecure attachment to father. 2) The different profiles were also expected to associate differently with adolescents’ so- cioemotional measures as follows: a) adolescents classified as securely attached to both parents will report lower levels of socioemotional difficulties compared to adolescents classified as securely attached to only one parent and b) adolescents clas- sified as insecurely attached to both parents will report higher levels of socioemotional difficulties compared to adolescents classified as securely attached to one parents. Sex differences regarding adolescents’ attachment relationships with fathers and mothers were also explored, without predicting a specific direction of findings due to prior mixed findings regarding sex differences in attachment relations (Lieberman et al., 1999; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Method Participants Participants comprised 203 typically developing adolescents (119 girls, 84 boys) sampled from 10 different classrooms in two public high schools in an urban area of central Israel: 102 tenth graders and 101 eleventh graders. The two schools were recommended by the Ministry of Education as similar in struc- ture and orientation, and as serving a similar population in terms of SES (middle-class). Adolescents’ reports of paren- tal marital status yielded 181 married couples (89%) and 22 divorced (11%). Approximately 10% of the children in each classroom had been formally diagnosed with disabilities such as learning dis- abilities and/or attention deficit-hyperactive disorder and were therefore excluded from this sample. Initial analyses examining age effects revealed no significant differences between the two grade levels on the study variables; therefore, all further analy- ses related to the two grade levels as one group. Instruments Four self-report measures were completed by adolescents. This selection of self-reports rather than assessments by sig- nificant others (parents, teachers, peers) corresponds with prior studies emphasizing the higher reliability found for children's and adolescents’ self-reports when measuring internalizing characteristics and perceptions of close relationships (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1997; Ronen, 1997). Attachment Security Style (Kerns, Klepac, & Cole, 1996). Prior studies of adolescents’ attachment used various self-report measures like the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998), Attachment Interview for Childhood and Adolescence (Ammaniti, Van IJzendoorn, Sper- anza, & Tambelli, 2000), or the Attachment Questionnaire (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). However, these global measures did not assess adolescents’ specific relations with each parental attachment figure. In line with previous valid outcomes for the Attachment Security Style scale (Kerns et al., 1996) in early adolescents (Lieberman et al., 1999), its 15-item Hebrew adap- tation (Granot & Maysless, 2001) was utilized here to assess adolescents’ perceptions of attachment security with each par- ent. The scale was administered twice, once about mothers and once about fathers, using Harter’s (1982) 4-point “Some kids …other kids” format. After reading a dual statement like “Some adolescents find it easy to trust their mom/dad BUT other kids are not sure if they can trust their mom/dad,” ado- lesencts chose which statement was more characteristic of them, and then indicated if the statement was really true for them or sort of true for them. Scores for each parent ranged from 15 to 60, with a categorical cut-off point of 45 distinguishing secure from insecure child-parent attachment (Kerns et al., 1996). Higher scores reflected more secure relations. The current Cronbach alphas were .85 for child-mother scale and .90 for child-father scale. Peer-Network Loneliness and Peer-Dyadic Loneliness Scale (PNDLS; Hoza et al., 2000). This 16-item scale assessed two subscales of loneliness using Harter’s (1982) 4-point “Some kids …other kids” format. Peer-network loneliness comprised 8 items such as “Some kids hardly ever feel accepted by others their age—but—other kids feel accepted by others their age most of the time”. The peer-dyadic loneliness com- prised 8 items such as “Some kids don’t have a friend that they can talk to about important things—But—others kids do have a friend that they can talk to about important things”. In the cur- rent study, the Cronbach alphas were .85 for the Peer-network loneliness subscale and .86 for the peer-dyadic loneliness sub- scale. Affect Scale (Moos, Cronkite, Billings, & Finney, 1987). For this 28-item two-factor scale (Hebrew adaptation—Margalit & Ankonina, 1991), participants rated the extent to which each item described their affect in the last month, on a 5-point scale ranging from Not at all (1) to Very much (5). The 14-item posi- tive affect factor included a positive affect subscale and a self-confidence subscale (e.g., “energetic,” “happy;”). The 14- item negative affect factor included a negative affect subscale and a global depression subscale (“feel guilty,” “worried;”). In the current study, the Cronbach alphas were .84 for the positive affect subscale and .88 for the negative affect subscale. “Internalizing Syndrome” Scales from the Standardized YSR—Youth Self-Report Version for Age 11-18 (Achenbach, 1991). This standardized instrument comprised 112 items ad- dressing emotional and behavioral problems among youth (He- brew adaptation; Zilber, Auerbach, & Lerner, 1994) on a 3-point scale ranging from Not true (0) to Very/Often true (2). Achenbach’s (1991) principal components analyses yielded eight narrow-band syndrome scales and two broad-band syn- drome scales (i.e., “internalizing syndrome” and “externalizing syndrome”). The present study used the broad-band “internal- izing syndrome” scale, referring to 30 internalizing behaviors (e.g., “rather be alone” or “nervous”), with a Cronbach alpha of .89. Procedure After obtaining parental consent and approval from the Is-  M. AL-YAGON 294 raeli Ministry of Education, one member of the research team (comprising graduate students in education counseling) entered each classroom. At the start of the session, the team member distributed a set of four questionnaires (attachment, loneliness, affect, and internalizing syndrome behavioral subscale) to each adolescent present in class. Before asking adolescents to com- plete the questionnaire packet, the team member read sample items aloud from each scale to ensure adolescents’ understand- ing. During the session, as adolescents individually completed the scales, the team member provided additional help to ado- lescents per need. To maintain adolescents’ privacy, teachers were not present in class during data collection. Questionnaires completed by adolescents with disabilities (i.e., approximately 10% in each classroom) were excluded from the current sam- ple. Results Descriptive Statistics Two analyses were conducted before the cluster analysis. To investigate the prevalence of adolescents’ attachment classifi- cations with fathers and mothers, adolescents were assigned either a secure or insecure classification for their adoles- cent-mother attachment and their adolescent-father attachment, in line with the categorical cutoff score (of 45) on the self-reported attachment scale (Kerns et al., 1996). The current results showed that whereas 72% of these adolescents were classified as securely attached to their mothers, only 61% were classified as securely attached to their fathers. That is, 39% of these adolescents were classified as insecurely attached to their fathers, but only 28% were classified as insecurely attached to their mothers. Second, further chi-square tests were conducted to examine adolescents’ sex differences regarding the prevalence of ado- lescents’ attachment classifications with fathers and mothers. No significant associations emerged between sex and attach- ment classification distributions with mothers or fathers, indi- cating that girls and boys reported a similar prevalence of at- tachment classifications with each parent. Therefore, all further analyses related to the boys and girls as one group. Likewise, as mentioned above, all further analyses related to the two grade levels as one group. Cluster Analysis This section presents analyses that were designed to examine the nature of the interrelations among identified attachment profiles of adolescents and the possible associations of these profiles to adolescents’ socioemotional difficulties. Subgroups with different profile s. To identify subgroups of adolescents with different individual profiles, k-means cluster analysis was performed with two individual factors: adoles- cents’ attachment style classification (secure/insecure) with father and with mother. As suggested by prior studies, the k-means iterative method makes multiple passes through the data, assigning units to the cluster with the nearest vector or set of means for the two variables, which is called the cluster cen- ter or centroid (Hammett, Kleeck, & Huberty, 2003). The final cluster solution revealed four distinct profiles. Cluster A (n = 15; 7.4% of sample) comprised adolescents classified as se- curely attached to father and insecurely attached to mother. Cluster B (n = 108; 53.2% of sample) comprised adolescents classified as securely attached to both parents. Cluster C (n = 42; 20.7% of sample) comprised adolescents classified as inse- curely attached to both parents. Cluster D (n = 38; 18.7% of sample) comprised adolescents classified as securely attached to mother and insecurely attached to father. To examine the internal validity of the cluster identification, a MANOVA was performed with the adolescents’ scores for attachment with father and attachment with mother as the de- pendent variables and with the cluster classification as the in- dependent variable. The MANOVA (using Wilks Lambda) yielded a significant main effect for the clusters’ identification, F (6, 396) = 119.30, p < .001, partial Eta squared = .64. As seen in Table 1, significant intergroup differences emerged for the four clusters, both on attachment scores with father and with mother, indicating that the cluster analysis identified four dif- ferent clusters according to their defining variables. In addition, χ2 tests yielded non-significant associations be- tween adolescents’ sex and the four clusters as well as between adolescents’ grade and the four clusters. Profiles’ links to adolescents’ adjustment measures. To examine whether these four different attachment profiles would link differentially with adolescents’ socioemotional and behav- ioral adjustment, a MANOVA (using Wilks Lambda) was conducted with the five adjustment measures as the dependent variables (positive and negative affect, peer-network and peer-dyadic loneliness, and internalizing behavior problems), and with the cluster classification as the independent variable. The analysis yielded a significant main effect for the clusters’ identification, F (15, 538) = 3.66, p < .001, partial Eta squared = .09. Univariate ANOVAs revealed significant main effects for the clusters’ classification for all the adjustment measures (see Ms, SDs, and F scores in Table 2). The two types of post hoc Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and statistical comparison of the four adolescents’ profiles by the two defining variables. Cluster A—Secure with father only (N = 15) Cluster B—Secure with both parents (N = 108) Cluster C—Insecure with both parents (N = 42) Cluster D—Secure with mother only (N = 38) F (3, 199) η2 Post hoc Scores M SD M SD M SD M SD Attachment to father 50.06 3.73 52.30 4.03 36.70 5.80 36.90 6.91 148.25* .69 A > C, D B > C, D Attachment to mother 39.46 4.07 52.80 3.94 39.70 4.47 50.70 4.30 130.00* .66 A < B, D B > A, C, D C < B, D *p < .001.  M. AL-YAGON 295 Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and statistical comparison of the four adolescents’ profiles by adolescents’ interpersonal and intrapersonal measures. Variable Cluster A—Secure with father only (N = 15) Cluster B—Secure with both parents (N = 108) Cluster C—Insecure with both parents (N = 42) Cluster D—Secure with mother only (N = 38) F (3, 199) η2 Post hoc M SD M SD M SD M SD Negative affect 33.80 11.18 28.0 8.70 35.36 9.14 35.65 12.63 9.35** .12 B < C, D Positive affect 49.20 7.20 53.11 7.08 46.88 7.57 48.92 7.95 8.57** .11 B > C, D Peer-network loneliness 13.27 2.65 11.74 3.25 14.80 4.82 13.84 3.69 8.25** .11 B < C, D Peer-dyadic loneliness 11.33 3.84 10.40 3.25 13.05 4.92 12.21 3.97 5.61** .08 B < C Internalizing behavior problems 8.47 7.11 7.54 6.67 14.14 8.56 13.55 9.43 10.63** .14 B < C, D *p < .01. **p < .001. analyses examining intergroup differences, Tukey HSD and Scheffe procedures, both revealed significant differences among three of the four clusters (B, C and D), on all the ado- lescents’ measures. With regard to Cluster A, the findings were at odds with our hypotheses, indicating that adolescents from Cluster A did not significantly differ from the other groups. Adolescents’ positive and negative affect. Significant inter- group differences emerged between three of the four clusters for adolescents’ self-rated negative affect: Clusters B, C, and D. An examination of group means indicated that adolescents from Cluster B (secure attachment with both parents) reported lower feelings of negative affect than adolescents from Cluster C (insecure attachment with both parents) and from Cluster D (secure attachment only with mother) (see Table 2). Likewise, significant intergroup differences emerged among the same three clusters (Clusters B, C, and D) for adolescents’ self-rated positive affect. Group means indicated that adoles- cents from Cluster B (secure attachment with both parents) reported higher feelings of positive affect than adolescents from Cluster C (insecure attachment with both parents) and from Cluster D (secure attachment only with mother) (see Table 2). Adolescents’ peer-network and peer-dyadic loneliness. Sig- nificant intergroup differences emerged between Clusters B, C, and D for adolescents’ self-rated peer-network loneliness. Group means indicated that adolescents from Cluster B (secure attachment with both parents) reported lower feelings of peer-network loneliness than adolescents from Cluster C (inse- cure attachment with both parents) and from Cluster D (secure attachment only with mother) (see Table 2). In contrast, sig- nificant intergroup differences in peer-dyadic loneliness emerged only between Clusters B and C. Group means indi- cated that adolescents from Cluster B (secure attachment with both parents) reported lower feelings of peer-dyadic loneliness than adolescents from Cluster C (insecure attachment with both parents) (see Table 2). Adolescents’ internalizing behavior problems. Significant intergroup differences emerged between Clusters B, C, and D for adolescents’ self-rated internalizing behavior problems. Group means indicated that adolescents from Cluster B (secure attachment with both parents) reported a lower level of inter- nalizing behavior problems compared to adolescents from Cluster C (insecure attachment with both parents) and from Cluster D (secure attachment only with mother) (see Table 2). Discussion The current study aimed to further explore the links between adolescents’ attachment relationships with both parents versus one parent, to obtain a deeper understanding of socioemotional adjustment, in this developmental period, when attachment behaviors may manifest differently than at earlier ages (e.g., Allen & Land, 1999; Steinberg, 1990) and when the prevalence rate for internalizing problems shows an increase (Lee & Hankin, 2009; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Overall, the current findings supported the study hypotheses, emphasized that the four different profiles of adolescents’ secure attachment rela- tionships were differentially associated with all of the tested socioemotional measures. Two descriptive statistics analyses were conducted before the cluster analysis. First, these findings yielded a higher preva- lence of adolescents’ secure attachment with mothers than with fathers. These results were similar to prior reports on children of school age (Verschueren & Marcoen, 2005) as well as ado- lescents (Lieberman et al., 1999; Paterson, Field, & Pryor, 1994; Youniss & Smollar, 1985). Second, the current finding that male and female adolescents reported a similar prevalence of secure attachment with their parents supports the non-signifi- cant sex differences found recently for children in middle childhood (Booth-Laforce et al., 2006) and also coincides with the assumptions underlying attachment theory, suggesting that attachment security does not vary as a function of children's sex (Bowlby, 1973, 1982/1969). In contrast, these findings differed from other studies suggesting that mothers tend to remain emo- tionally involved with both their sons and daughters during adolescence, whereas a decrease with age occurs in girls’ per- ception of closeness and comfort in their relationships with their fathers (Lieberman et al., 1999; Youniss & Smollar, 1985). To explore these inconsistent findings more comprehensively, future studies should investigate the longevity of adolescents’ perceptions of attachment relations with fathers and mothers over time. Profiles of Adolescents’ Attachment Relations with Father and Mother As hypothesized, four distinct profiles of adolescents’ secure attachment relationships with parents emerged: secure attach-  M. AL-YAGON 296 ment with both parents, with neither parent, with mothers only, and with fathers only. The largest cluster, comprising 53% of the sample, comprised adolescents with a secure attachment classification with both their father and their mother. About 21% of adolescents formed the cluster with an insecure attach- ment classification with both parents. The remaining two pro- files exhibited secure attachment with either mothers only (19%) or fathers only (7%). Due to the aforementioned paucity of research on the preva- lence of typically developing adolescents' secure attachment to one versus both parents, the current sample's distribution into the four profiles appears to provide important initial informa- tion. The few existing studies on attachment to both parents mainly focused on the unique role of secure attachment to each parent separately (Booth-Laforce et al., 2006; Germeijs & Ver- schueren, 2009; Lieberman et al., 1999; Margolese, Markiewicz, & Doyle, 2005; Verschueren & Marcoen, 2005). Thus, the four specific profiles that emerged here merit further consideration in future research to help unravel adolescents’ relationships during this developmental period, when family relations remain crucial yet show increased parent-adolescent conflicts and squabbling, which, in turn, may affect feelings of closeness and the amount of time that adolescents and parents spend together (Allen, 2008; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Moreover, the current results raise an additional important question: Do the perceived attachment relationships with the father and the mother become more integrated or more differ- entiated over the course of adolescence? As suggested by Allen and Land (1999), during the adolescent period, along with an augmented ability to differentiate between the qualities of spe- cific relationships with each parent, adolescents may also de- velop an integrated strategy of approaching attachment rela- tionships. Within this context, future research on the integration and differentiation of adolescents’ perceptions of attachment with parental figures may do well to include complementary methods such as interview-based measures. Profiles’ Links with Adolescents’ Socioemotional Adjustment As hypothesized, the present findings indicated that the dif- ferent profiles of attachment with parents linked significantly with differences in adolescents’ socioemotional adjustment: positive/negative affect, peer-network/peer-dyadic loneliness, and internalizing behavior problems. Overall, the present study clearly revealed significant group differences between Clusters B, C, and D concerning all of the adolescents’ socioemotional measures. However, with regard to Cluster A, the findings were at odds with our hypotheses, indicating that adolescents who felt securely attached only with the fathers did not significantly differ from the other groups, possibly because of the small size of this group, which consisted of only 15 adolescents. Affect. As mentioned above, this two-part measure (com- prising negative and positive affect) is considered important for understanding individuals’ mental health (Clark & Watson, 1988; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). As hypothesized, the current results indicated that the different profiles held utility in understanding differences in adolescents’ affect for both sub- scales. Thus, adolescents who felt securely attached to both parents seemed less vulnerable to higher negative affect and lower positive affect, compared to adolescents who only felt securely attached with their mothers or who felt insecurely attached with both parents. Interestingly, adolescents who felt securely attached only with the father did not significantly dif- fer from adolescents from the other three profiles, regarding their affective levels. Other studies have likewise reported on the association be- tween adolescents’ attachment relationships and affects (e.g., Margolese et al., 2005; Wilkinson & Walford, 2001); however, the current investigation may expand knowledge regarding this link in two major ways. First, most studies on adolescents’ affect focused on negative affect such as depression and anxiety (Irons & Gilbert, 2005; Lee & Hankin, 2009; Margolese et al., 2005); therefore, the current study’s focus on both negative and positive affect may add a small but growing body of evidence linking patterns of attachment and emotional experiences in this developmental period. These results may be particularly im- portant in light of prior studies that reported an increase of negative emotions, a reduction of positive emotions, and greater emotional lability during this developmental phase (Irons & Gilbert, 2005; Larson, 2000; Lee & Hankin, 2009). Second, most research on adolescents’ attachment relations focused on their global representation of attachment patterns (e.g., Lee & Hankin, 2009; Wilkinson & Walford, 2001), whereas attachment relations with each specific parental figure were rarely examined (Margolese et al., 2005). Therefore, the present results may uniquely pinpoint that adolescents’ inter- personal relationships with fathers are equally protective as their relationships with mothers, in understanding adolescents’ negative and positive affect. Loneliness. The current investigation revealed slightly dif- ferent results for each of the two types of loneliness examined simultaneously: peer-network and peer-dyadic loneliness. Ado- lescents who felt securely attached to both parents reported lower peer-network loneliness than adolescents who only felt securely attached with the mother or who felt insecurely at- tached with both parents. In contrast, adolescents who felt se- curely attached to both parents only reported lower peer-dyadic loneliness compared to adolescents who felt insecurely attached with both parents. In other words, secure attachment with both parents seemed to play an equally protective role as secure attachment with only mothers in ameliorating lonely experi- ences in peer dyads, such as feelings of lacking peer support or closeness to a peer. Conversely, secure attachment with moth- ers did not act as a protective factor ameliorating lonely ex- periences in larger peer networks, such as feelings of being excluded or rejected by the peer group. Taken together, these results for loneliness coincide with prior studies across a wide range of samples that demonstrated the link between insecure attachment and high loneliness levels (Al-Yagon, 2007; Al-Yagon & Mikulincer, 2004; Qualter & Munn, 2002; Weimer, Kerns, & Oldenburg, 2004), although the constructs of peer-network and peer-dyadic loneliness were less investigated among adolescents. As argued by attachment the- ory, individuals’ “internal working models” provide a general expectation of what relationships are like and guide individuals' later affects and behaviors in close relationships with signifi- cant extrafamiliar others (Bowlby, 1973; Waters & Cummings, 2000). This theoretical framework thus sees loneliness as a form of separation distress that stems from failure to meet basic attachment needs (Weiss, 1973).  M. AL-YAGON 297 The current findings for loneliness may also uniquely high- light the possible role of adolescents’ close relationships with fathers in protecting adolescents from experiencing peer-net- work loneliness. These results may support previous findings that suggested that secure attachment relationships with the mother may best predict a child’s functioning in intimate small groups or dyadic interactions, whereas secure attachment with the father may best predict peer acceptance (Verschueren & Marcoen, 2005). Future research should examine the longevity of such associations over time and utilize qualitative interview methods to elaborate on these adolescent’s structured self-re- ports. Internalizing behavior problems. Consistent with the pre- sent study hypothesis, significant differences emerged between profiles for adolescents’ internalizing behavior problems. Thus, adolescents who did not feel securely attached with either par- ent evaluated themselves as manifesting significantly more internalizing maladjustment problems such as preferring to be alone, refusing to talk, shyness, or fearfulness, compared to adolescents who felt securely attached with both parents or with the mother. These outcomes resembled prior ones suggesting links between youngster’s insecure patterns of attachment and high levels of internalizing problems (e.g., Greenberg, 1999; Muris et al., 2003). However, most past research focused on attachment relations with the mother or global representations of attachment patterns; hence, the current study may offer some new knowledge on the possible role of each versus both at- tachment figures in explaining adolescents’ differences in so- cioemotional maladjustment problems. Conclusions, Limitations, and Directions for Future Study In sum, the present study addressed two core questions: (a) Do adolescents hold constructed separate representations of their attachment relationships with each parent, or one overall generalized representation of attachment relationships? and (b) How, if at all, do adolescents’ specific profiles of close rela- tions (i.e., secure/insecure attachment to one/both parents) as- sociate with their socioemotional and behavioral problems? These questions are of particular interest because their preva- lence rate shows an increase during adolescence that continues into adulthood (Lee & Hankin, 2009; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). As hypothesized, four different profiles of adolescents’ secure attachment relationships with parents emerged, and three of these clusters (B, C, and D) were differentially linked with all of the adolescents’ socioemotional measures. The findings for Cluster A (adolescents who felt securely attached only with the father) were at odds with our hypotheses, probably reflect- ing the small size of this group. Unsurprisingly, the group of adolescents who felt securely attached to both parents (Cluster B) was least vulnerable to experiencing socioemotional difficulties. Interestingly, secure attachment only to one's mother and not to one's father (Cluster D) did not seem to act as a protective factor, with the exception of protecting this group from peer-dyadic loneliness—a type of loneliness conjectured as related to early sets of social experi- ences specific to the mother (Verschueren & Marcoen, 2005). This pattern of findings highlights the need to further scrutinize the role of close relations with fathers in the adolescent devel- opmental period. Overall, these findings may have several implications, espe- cially when validated by further research, for designing effec- tive prevention and intervention concerning socioemotional difficulties in adolescence. Such designs may focus on enhanc- ing the quality of parent-adolescent attachment relations, in- cluding strategies for empowering parents to establish a secure base for their adolescent offspring such as encouraging col- laborative rather than coercive parenting strategies, under- standing the role of conflict in adolescence, and dealing with youngsters’ emerging need for autonomy (Diamond, Siqueland, & Diamond, 2003; Moretti & Obsuth, 2009). Further studies attempting to develop such programs should examine their effectiveness in buffering adolescents’ socioemotional and behavioral problems. Considering the important role found for adolescent-father close relations, such interventions may also do well to focus on enhancing fathers’ level of involvement, availability, and support, in order to provide more optimal care and secure base in this developmental period (Lamb & Billings, 1997; Saloviita, Itälinna, & Leinonen, 2003). Several limitations in the design and variable selections de- serve mention. First, conceptual matters merit a word of caution despite the interesting associations found between adolescents’ attachment classifications and socioemotional measures. Inas- much as parent-adolescent attachment is set within a broader context, additional aspects of these relationships should be considered, such as parenting styles and monitoring levels, various life stressors and changes, etc. Second, the current data were gathered at one point in time and did not indicate causality. Therefore, it is possible that high levels of socioemotional dif- ficulties underlie adolescents’ perceptions regarding parents as an insecure base rather than vice versa. Third, the current data focused exclusively on adolescents’ perceptions, in line with prior studies emphasizing the higher reliability found for chil- dren's and adolescents’ self-reports compared to others’ reports, when measuring internalizing characteristics and perceptions of close relationships (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1997; Ronen, 1997). However, it may be assumed that inclusion of additional infor- mation sources such as parental and peer evaluations, direct observations, and interviews may provide a more complete picture. Fourth, the present study categorized the adolescents into four groups according to the categorical cut-off point of 45 distinguishing secure from insecure child-parent attachment (Kerns et al., 1996). Within each of these groups, adolescents may have demonstrated a slight degree of variance regarding their attachment scores. Thus, future studies would do well to use additional non-categorical procedures to pinpoint possible individual differences. Fifth, the current study utilized Kerns et al.’s (1996) well-known and well-validated Attachment Security Style scale, as implemented in many studies on children as well as early adolescents. However, this scale focuses on a two-part classifi- cation of attachment, differentiating only secure vs. insecure styles. To further understand the interrelationships between the current study’s measures, future research may do well to ex- amine the possible unique contribution of two insecure attach- ment subclassifications—insecure avoidant style and insecure anxious style—in explaining adolescents’ socioemotional ad- justment and maladjustment functioning. Finally, the present sample showed a high prevalence of intact families. Therefore, the current outcomes should be interpreted with caution, to  M. AL-YAGON 298 avoid generalizing the findings to divorced or separated fami- lies. References Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist: 4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. Achenbach, T. M., & Dumenci, L. (2001). Advances in empirically based assessment: Revised cross-informant syndromes and new DSM-oriented scale for CBCL, YSR, and TRF: Comment of Lengua, Sadowski, Friedrich, and Fisher (2001). Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 69, 699-702. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.4.699 Ainsworth, M. D., & Wittig, B. A. (1969). Attachment and exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of infant behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 113-136). London: Methuen. Allen, J. P. (2008). The attachment system in adolescence. In J. Cassidy and P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 419-435). New York: Guilford Press. Allen, J. P., & Land, D. (1999). Attachment in adolescence. In J. Cassidy and P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 223-319). New York: Guil- ford Press. Ammaniti, M., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Speranza, A. M., & Tambelli, R. (2000). Internal working models of attachment during late childhood and early adolescence: An exploration of stability and change. At- tachment and Human Development, 2, 328-346. Al-Yagon, M. (2007). Socioemotional and behavioral adjustment among school-age children with learning disabilities: The moderating role of maternal personal resources. Journal of Special Education, 40, 205-217. Al-Yagon, M., & Mikulincer, M. (2004). Patterns of close relationships and socio-emotional and academic adjustment among school-age children with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 19, 12-19. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2004.00085.x Asher, S., & Paquette, J. A. (2003). Loneliness and peer relations in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 75-78. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01233 Asher, S. R., Parkhurst, J. T., Hymel, S., & Williams, G. A. (1990). Peer rejection and loneliness in childhood. In S. R. Asher and J. D. Coie (Eds.), Peer rejection in childhood (pp. 253-273). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Booth-Laforce, C., Oh, W., Kim, A. H., Rubin, K. H., Rose-Kransor, L., & Burgess, K. (2006). Attachment, self-worth, and peer-group func- tioning in middle childhood. Attachment and Human Development, 8, 309-325. doi:10.1080/14616730601048209 Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Anxiety, anger, and separation. New York: Basic Books. Bowlby, J. (1982/1969). Attachment and loss: Attachment. New York: Basic Books. Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report meas- urement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson and W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close rela- tionships (pp. 46-76). New York: Guilford Press. Brennan, T. (1982). Loneliness at adolescence. In L. A. Peplau and D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 269-290). New York: John Wiley & Sons. Chen, X., He, Y., De Oliveira, A. M., Coco, A. L., Zappulla., C., Kaspar, V., Schneider, B., Valdivia, I. A., Tse, H. C., & DeSouza, A. (2004). Loneliness and social adaptation in Brazilian, Canadian, Chinese and Italian children: A multi-national comparative study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1373-1384. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00329.x Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1988). Mood and the mundane: Relations between daily life events and self-report mood. Journal of Personal- ity and Social Psychology, 54, 296-308. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.2.296 Dahl, R. E. (2004). Adolescents’ brain development: A period of vul- nerabilities and opportunities. Annals New York Academy of Sciences, 1021, 1-22. doi:10.1196/annals.1308.001 Diamond, G., Siqueland, L., & Diamond, G. M. (2003). Attach- ment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents: Programmatic treatment development. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Re- view, 6, 107-127. doi:10.1023/A:1023782510786 Engels, R. C., Finkenauer, C., Dekovic’, M., & Meeus, W. (2001). Parental attachment and adolescents’ emotional adjustment: The as- sociation with social skills and relational competence. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48, 428-439. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.48.4.428 Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review in Psychology, 55, 745-774. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456 Germeijs, V., & Verschueren, K. (2009). Adolescents’ career decision making process: Related to quality of attachment to parents? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 459-483. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00603.x Granot, D., & Maysless, O. (2001). Attachment security and adjustment to school in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25, 530-541. doi:10.1080/01650250042000366 Greenberg, M. T. (1999). Attachment and psychopathology in child- hood. In J. Cassidy and P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 469-496). New York: Guilford Press. Goossens, L. (2006). Affect, emotion, and loneliness in adolescence. In S., Jackson and L. Goossens (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent devel- opment (pp. 51-70). Psychology Press: New York. Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Fremmer-Bombil, E., Kindler, H., Scheurer-Englisch, H., & Zimmermann, P. (2002). The uniqueness of the child-father attachment relationships: Fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16-year long study. Social Development, 11, 307-331. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00202 Grossmann, K. E., Grossmann, K., & Waters, E. (2006). Attachment from infancy to adulthood. New York: Guilford Press. Hammett, L. A., Kleeck, A. V., & Huberty, C. J. (2003). Patterns of parents’ extratextual interactions during book sharing with preschool children: A cluster analysis study. Reading Research Quarterly, 38, 442-450. doi:10.1598/RRQ.38.4.2 Harter, S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87-97. doi:10.2307/1129640 Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 Hoza, B., Bukowski, W. M., & Beery, S. (2000). Assessing peer net- work and dyadic loneliness. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 119-128. doi:10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_12 Irons, C., & Gilbert, P. (2005). Evolved mechanisms in adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms: The role of the attachment and social rank systems. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 325-341. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.07.004 Jackson, S., & Goossens, L. (2006). Handbook of adolescent develop- ment. Psychology Press: New York. Kerns, K. A., Klepac, L., & Cole, A. (1996). Peer relationships and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in the child-mother relation- ship. Developmental Psychology, 32, 457-466. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.3.457 Lamb, M. E. (2002). Infant-father attachments and their impact on child development. In C. Tamis-LeMonda and N. Cabrera (Eds.), Hand- book of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 93-117). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Lamb, M. E., & Billings, L. A. L. (1997). Fathers of children with special needs. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (3rd ed., pp. 179-190). New York: John Wiley & Sons. Larson, R. (2000). Towards psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55, 170-183. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170 Lee, A., & Hankin, B. L. (2009). Insecure attachment, dysfunctional  M. AL-YAGON 299 attitudes, and low self-esteem predicting prospective symptoms of depression and anxiety during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38, 219-231. doi:10.1080/15374410802698396 Lieberman, M., Doyle, A., & Markiewicz, D. (1999). Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late child- hood and early adolescence: Associations with peer relations. Child Development, 7, 202-213. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00015 Lynch, M., & Cicchetti, D. (1997). Children’s relationships with adult and peers: An examination of elementary and junior high school stu- dents. Journal of School Psychology, 35, 81-99. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(96)00031-3 Mahon, N. E. (1983). Developmental changes and loneliness during adolescence. Topics in Clinical Nursing, 5, 66-76. Margolese, S. K., Markiewicz, D., & Doyle, A. B. (2005). Attachment to parents, best friend, and romantic partner: predicting different pathways to depression in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Ado- lescence, 34, 637-650. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-8952-2 Margalit, M., & Ankonina, D. B. (1991). Positive and negative affect in parenting disabled children. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 4, 289-299. doi:10.1080/09515079108254437 Marsiglio, W., Amato, P., Day, R. D., & Lamb, M. E. (2000). Scholar- ship on fatherhood in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Marriage and the family, 62, 1173-1191. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01173.x Maysless, O., & Scharf, M. (2007). Adolescents’ attachment represen- tations and their capacity for intimacy in close relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27, 23-50. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00511.x Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press. Moos, R. H., Cronkite, R. L., Billings, A. G., & Finney, J. W. (1987). Revised health and daily living form manual. Palo Alto, CA: Veter- ans Administration and Stanford University Medical Centers. Moretti, M, & Obsuth, I. (2009). Effectiveness of an attachment-focused manualized intervention for parents of teens at risk for aggressive be- havior: The connect program. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 1347-137. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.013 Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Van den Berg, S. (2003). Internalizing and externalizing problems and correlates of self-reported attachment style and perceived parental rearing in normal adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 12, 171-183. doi:10.1023/A:1022858715598 Parke, D. R. (2004). Development in the family. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 365-399. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141528 Parke, D. R., Dennis, J., Flyr, M. L., Morris, K. L., Killian, C., Mcdow- ell, D. J., & Wild, M. (2004). Fathering and child peer relationships. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 307-340). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. Paterson, J. E., Field, J., & Pryor, J. (1994). Adolescents’ perceptions of their relathionships with their mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23, 579-592. doi:10.1007/BF01537737 Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In L. A. Peplau and D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of cur- rent theory, research and therapy (pp. 1-18). New York: John Wiley & Sons. Qualter, P., & Munn, P. (2002). The separateness of social and emo- tional loneliness in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 233-244. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00016 Richaud de Minzi, M. C. (2006). Loneliness and depression in middle and late childhood: The relationship to attachment and parental style. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 167, 189-210. doi:10.3200/GNTP.167.2.189-210 Ronen, T. (1997). Cognitive-developmental therapy with children. Chichester, England: Wiley. Saloviita, T., Itälinna, M., & Leinonen, E. (2003). Explaining the pa- rental stress of fathers and mothers caring for children with intellec- tual disability: A double ABCX model. Journal of Intellectual Dis- ability, 47, 300-312. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00492.x Schults, N. R., & Moor, D. (1988). Loneliness: Differences across three age levels. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 5, 275-284. doi:10.1177/0265407588053001 Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2003). Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development, 74, 1869-1880. doi:10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x Song, H., Thompson, R. A., & Ferrer, E. (2009). Attachment and self evaluation in Chinese adolescents: Age and gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 1267-1286. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.01.001 Steinberg, L. (1990). Interdependency in the family: Autonomy, con- flict, and harmony in the parent-adolescent relationship. In S. Feldman and G. Elliott (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing ado- lescent (pp. 255-276). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83-110. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83 Verschueren, K., & Marcoen, A. (2005). Perceived security of attach- ment to mother and father: Developmental differences and relation to self-worth and peer relation at school. In K. A. Kerns and R. A. Richardson (Eds.), Attachment in middle school (pp. 212-230). New York: Guilford Press. Waters, E., & Cummings. E. M. (2000). A secure base from which to explore close relationships. Child Development, 71, 164-172. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00130 Weimer, B. L., Kerns, K. A., & Oldenburg, C. M. (2004). Adolescents’ interactions with a best friend: Association with attachment style. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88, 102-120. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2004.01.003 Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and so- cial isolation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Wilkinson, R. B., & Walford, W. A. (2001). Attachment and personal- ity in the psychological health of adolescents. Personality and Indi- vidual Differences, 31, 473-484. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00151-3 Youniss, J., & Smollar, J. (1985). Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers, and friends. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Zilber, N., Auerbach, J., & Lerner, Y. (1994). Israeli norms for the Achenbach child behavior checklist: Comparison of clinically-referred and non-referred children. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Science, 31, 5-12.

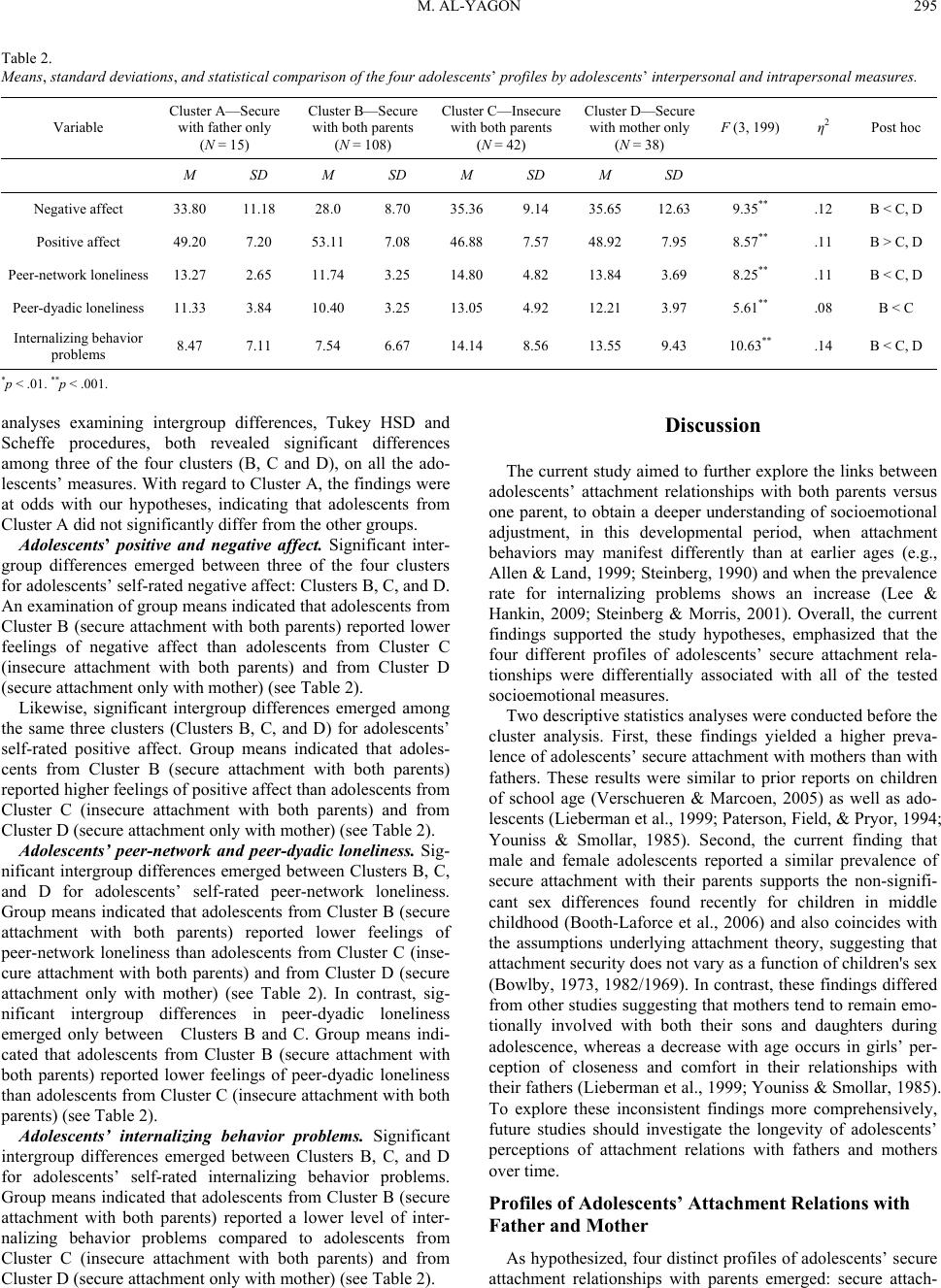

|