Intelligent Information Management, 2015, 7, 303-312 Published Online November 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/iim http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/iim.2015.76024 How to cite this paper: Reis, M., Silva, R., Romão, A. and Saias, J. (2015) BigPicture: An Analytical Platform for Business War Gaming. Intelligent Information Management, 7, 303-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/iim.2015.760 24 BigPicture: An Analytical Platform for Business War Gaming Miguel Reis1, Ruben Silva1, Artur Romão1, José Saias2 1Cortex Intelligence, Évora, Portugal 2University of Évora, Évora, Portugal Received 26 September 2015; accepted 13 November 2015; published 16 November 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Business war games are strategic management exercises that bring the military scenario simula- tion to a commercial setting, helping business managers to better understand the environment in which they operate and anticipate scenarios, such as competition movements, new product launch- ing and production capacity planning, among others. These exercises normally take place with players organized in teams, gathered in a room, with a static package of information provided be- forehand. In this paper we present an alternative, dynamic way of playing a business war game, with players geographically dispersed, and information dynamically available as it is available from its sources. We introduce BigPicture, an analytical platform with unique features that allow it to be an ideal “playground” for conducting more realistic business war games. Keywords Business Intelligence, Analytical Platform, Simulation, War Game, Gamification 1. Introduction It is commonplace to say that business landscape changes faster every day, posing increasingly complex chal- lenges to decision makers. Obtaining relevant information has always been a concern. In the d istant 1958, Luhn referred to intelligence, in business context, as “the ability to apprehend the interrelationships of presented facts in such a way as to guide action towards a desired goal” [1]. Emerging technologies, social and economic changes, new regulations and compliance needs, competitors’ moves, changes in customer behaviour, are but a few factors to consider when trying to make informed decisions, be them about sales and marketing strategies, technology roadmaps, production capacity, partnerships, or mergers and acquisitions.  M. Reis et al. In all cases, a business manager facing a problem and trying to decide the best way to overcome it needs to have a good understanding about the current scenario, the level of uncertainty associated with it, the key players, and the possible outcomes. Only with this level of insight should she then move to a decision that minimizes the risk for the business. The military have for long been tackling the problem of anticipating future scenarios, and from there get their resources and strategies prepared, by playing “war games”, simulating moves and counter-moves in a belligerent setting [2]. In recent years, the business community has turned to this methodology and adapted it to the many “war” scenarios going on in global business [3]. In 2011, Deterding et al. defined gamification as “the use of game design elements in non-game contexts” [4], distinguishing it from related concepts, such as serious games. It provides enjoyment, or attains voluntarily user participation by offering challenging problem-solving tasks, or other fun facts, and can be utilized for informa- tion gathering [5] and other purposes. Business war gaming is an adaptation of the traditional military war games to a commercial setting, in the scope of a broader discipline called competitive intelligence (CI), practiced by business strategists looking to understand what is happening in the environment that surrounds a business [6]. They test beliefs and assump- tions about the business environment, identify emerging opportunities and threats, and build a better under- standing of industry issues. The objective is to improve corporate planning processes, and use the lessons learned from the game in business strategy. A key element to make business war gaming effective is the ability to collect and organize data from the ex- ternal environment, related to the problem being addressed, and then to transform those data into information that can help enable foresight into future scenarios and build proactive and/or better reactive strategies. Typically, business war games are conducted by strategic consultants who are responsible for collecting and organizing data, structuring and managing team interaction, assisting participants in understanding and acting upon the simulated moves and counter-moves, and finally providing insights and debriefing the results. While these activities require deep knowledge and expertise, they can all benefit from using appropriate technology that enhances data collection, organization, and analysis, freeing the players to focus on strategy. This paper presents B ig Picture, an analytical platform that automates the collection of targeted quantitative and qualitative data from virtually any source, and provides tools to blend and analyse those data in order to come up with knowledge that can be shared and acted upon by communities of business users. We describe a use-case of a business war game conducted entirely on this platform, wh ich he lp s f ast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) multinational to devise an expansion strategy in the face of a highly competitive mar- ket in Northern Europe. In the paper we focus on the technological issues that guide the development and con- figuration of the platform, as well as the challenges we face from an IT perspective. 2. Dynamics of a Business War Game War games typically involve a number of teams, each of them representing different players operating in the in- dustry environment. Generally, these teams represent different competitors. However, depending on the actual purpose and scope of the game, they can also include key customers and suppliers, or organizations like regula- tory bodies. Generally, the war game process involves a number of rounds. Each round represents a different time period, usually from several months to a few years. Shorter periods are less common, as the decisions taken would be- come tactical, rather than strategic in nature. Longer periods are also not common, as the uncertainty factors mean that war gaming would give less direction. 2.1. Coordi nator The teams are assisted by one or more elements (coordinators), generally with a strategic consulting background, that facilitate all the materials and information the players will need, manage the interaction between the teams and the workflow between the rounds, organize findings, and finally help participants with the conclusions. 2.2. Data Before the actual game starts, the coordinator (either an individual or a team) has to make sure players have enough,  M. Reis et al. relevant data within the framework of the game, i.e., companies, people, markets, economy, legislation, and so on. There will be financial and corporate data about competitors, collected from public web sources (or purchased from specialized providers, if the organization is willing to invest at this level); people’s profiles, taken from so- cial media like LinkedIn; market information, like shares, portfolios, and trends; social, economic and demo- graphic data, gathered from official statistics bodies; and relevant legislation, available from government web sites. In general, the coordinator gets these data each time he runs a business war game, meaning he will have to look for them, or at least update what he already has from previous games. After that, he must prepare the data so that players can understand and use it during the game. Usually, there are templates that make this task easier, although sometimes new sources or data formats mean extra work to adapt the templates. 2.3. Player Activities The exact activities players perform during a business war game depend, naturally, on the actual case being ad- dressed, its scope and goals. Players are organized in teams, each representing a company or organization in- volved in the “war” scenario (usually a competitor), and the game progresses through moves and counter-moves of each team. A move represents the decisions of the team in the face of the others’ own moves (i.e., decisions). The team members analyse what others have come up with, together with information available from the coordinator, dis- cuss the implications and alternatives for their own strategy, update any information structures they may be us- ing (see below), and generate the next move. During a move, the players use tools and frameworks that help them to organize information and systematize the outcome of decisions. Strategic models like Porter’s Five Forces and Four Corners, SWOT analysis, or benchmarking, are examples of such tools. They all provide information structures that help players organize what they know and from there make it easier for them to make informed decisions. The coordinator may assist each team in working with these data and tools, assuming a pedagogical role, but refrain from influencing the outcome in any way. 2.4. Game Conclusions Whether or not there will be a winner of the game is not a fundamental goal of playing it in the first place. Of course, having some kind of personal stimulus may be an additional factor for player engagement (that is the core of current gamification trends [7]), but the overall goal should be the exercise in itself, the learning each player gets from participating, and the value for the organization by having a group of talented people discussing and deciding about scenarios that they might actually be facing in the future. The coordinator finalizes the game by debriefing the participants about the path taken from the initial stage, the decision processes used by the players, the lessons learned, and how they can be used effectively in the or- ganization against similar situations in the future. He does this by delivering the conclusions in the form of a presentation and/or additional documentation, for future reference. 3. The BigPicture Platform We now present BigPicture, a cloud-based platform that aims to assist organizations that wish to rely on data and analytics to support their strategic decision processes. While it was not initially developed specifically to host business war games, it was enhanced with features that cover most of the steps and roles, greatly improving process effectiveness and user experience. Figure 1 depicts the fundamental components of BigPicture, from a functional point of view. As shown in the left side, BigPicture collects data from on-line sources, as well as from users, through forms. Data is then stored in specialized repositories, depending on their nature and purpose, and become available to be analysed. The platform includes a complete suite of tools for blending, analysing and visualizing data. The results are delivered to end users through configurable, interactive dashboards. The following sections describe each component in greater detail.  M. Reis et al. Figure 1. BigPicture overview. 3.1. Data Sources BigPicture collects data from external, on-line sources, both from those that are open to the public, as well as those that require a subscription to grant access (provided that the subscription is paid for). Data may be structured or unstructured, quantitative or qualitative. Users should only concern about what data they need, and where to get them, without regards to the format. Dealing with that is the job of the components presented below. For each data source there is a plug-in responsible for monitoring the source and automatically collecting all updates and new content made available. This way, the platform is permanently fed with relevant data from on-line and social media, blogs, stock quotes, commodity prices, statistics, and indexes, among many others. Data may also be input by users through web forms. BigPicture provides easy-to-use tools for structuring web forms. These will be used to capture user input, which will then be stored and analysed as any other content col- lected by the platform. The same technology is used to implement data structures that will contain textual data collected automati- cally, and then processed in order to extract meta-data (see below, on unstructured data repository). There is also the possibility to integrate internal data sources, like local databases, ERPs, and CRM systems, but that is not covered in this paper. 3.2. Data Repository Although this is completely hidden from end users, it is worth noting that data storage is of utmost importance in BigPicture. Naturally, there are performance and security issues to be addressed, and those are taken care of us- ing the best practices and technologies available. But the aspect to highlight here is that data are stored accord- ing to the purpose they will serve, and for that BigPicture provides a repository that can accommodate different types of data: • Unstructured, text-based content that can be indexed and enriched with meta-data, which, as mentioned pre- viously, are stored in forms. These forms can have several types of fields, from text to dates, numbers, lists of values, images, links, or videos. These operations provide the means to search the content, not only by traditional keyword searching, but also by contextual search based on semantic processing techniques, like named entity recognition, identifying terms as companies, people, or places, and allowing search and ana- lytics based on those entities. • Multi-dimensional databases that can be crossed in a number of dimensions and measures, and consolidated into structures called “analytical cubes”. For example, databases related to the market distribution (measure)  M. Reis et al. by month (time dimension) and by region, company or operating segments (business dimension). • Indexes, or time-series, i. e., one-dimensional variables that change over time, like exchange and stock rates, commodity prices, demographic and macro-economic indicators, among others. These are used to show us- ers the evolution of the indexes, and can be blended with multi-dimensional data. BigPicture incorporates technology that prepares data to be stored accordingly, as well as to make it available to be searched and analyzed by the following components. 3.3. Analytics BigPicture is, at its core, an analytical platform, that relies on data of different types and sources to perform complex analysis. Rather than following traditional big data-like approaches that focus on very large volumes of data, we have developed BigPicture with data diversity in mind, as a way to deliver valuable analytics, irrespec- tive of the volume of data. All data that needs to be analysed in BigPicture is modelled as multidimensional cubes. Even indexes (as a special case, with only one dimension) and forms (whose numeric fields become measures and non-numeric fields become dimensions) are abstracted as cubes. Then, analytics is performed as in a normal business intelligence system, with one particular differentiating factor: the analyst is completely free to blend different sources of data, by combining different cubes at the time of building the analysis. This is different from other approaches, where the blending of data has to start being planned at data modelling time, i.e., very early in the process, thereby limiting the flexibility the analyst may have when performing the analysis she wants. By allowing the analyst to make decisions at the latest moment possible, BigPicture provides complete freedom for trial and error, easy modification and adaptation to future needs. Figure 2 shows the tools provided for data analysts, providing a rich set of features to analyse data, including dimension filtering, dataset blending, definition of formulas to calculate new values, many visualization options, and so on. 3.4. Deliver y The final step in BigPicture’s value chain is the delivery of intelligence to users. This is done primarily through interactive dashboards, each of them starting as a “blank sheet,” where analysts include content units (document Figure 2. Analysis building tool.  M. Reis et al. lists, analysis, filters, images, static text, forms, tables, search tools, among others) using straightforward drag- and-drop features. Figure 3 illustrates the start of a new dashboard. With these tools, analysts can create dashboards with different layouts, depending on the needs of their end users, the organization of the information they want to make available, aesthetics and usability issues, and so on. Content units like document lists and analysis are dynamic, in the sense that as new content is fed into the plat- form they are updated accordingly. For example, if new articles are collected from on-line newspapers, they are automatically added to the lists, or if new stock quotes or statistics are gathered, every analysis that uses them is automatically updated. In Figure 4 we present some examples of dashboards that can be built in the platform. After creating the dashboards, the analyst organizes them hierarchically in a taxonomy of tabs, as shown in Figure 5, and thereby creating a structured web portal, where users can navigate and “consume” intelligence. There are additional methods for delivering information from the platform, like reports and alerts, but those will not be covered in this paper. Figure 3. Creating a new dashboard. Figure 4. Examples of dashboards in BigPicture.  M. Reis et al. Figure 5. Taxonomy of dashboards. 4. A Business War Game on BigPicture This section describes a real case of a business war game conducted entirely using the BigPicture platform, in early 2015, by a multinational company from the FMCG sector. For confidentiality reasons, the name of the company as well as other details will not be disclosed (hence the blurred words in some figures), as the main goal is to illustrate the execution of the game, and what was BigPicture’s contribution. 4.1. The Problem The company is a global player in the FMCG industry, and wanted to increase its market share in Europe, where it was facing fierce competition from other players, some of them being local companies and others being global players. The company was considering several alternative strategies to address this problem, and decided to run a business war game for that purpose. 4.2. Scope The scope included three countries, and there were seven teams per country (one representing the company, and the remaining six representing the competitors), with around fifty people involved, most of them being part of different teams, one for each country, as illustrated in Figure 6. This way, each participant had the opportunity to play for his company in one country, and for a competitor in another, making the experience even richer. The coordinator used BigPicture as a data purveyor, knowledge sharing and analytics platform, providing an “intelligence package” with data about: each market, the industry, and the players. This package included mar- ket, political, social, demographic, economic, and legal facts, drivers and assumptions, strategic profiles, and fi- nancial intelligence. These data was organized in the platform so that players would see general data shared with all participants, and specific data pertaining only to their own team. Some data were static and mainly quantitative, like financial and statistical figures about markets and compa- nies. Other would be more dynamic, both quantitative and qualitative, like news feeds about matters of interest to the scope of the game, stock quotes and other market figures, all of them being fed in (near) real time to the platform, to be made permanently available to the players. 4.3. Running the Game The platform was setup one month before the beginning of the game, in order to make sure enough data was loaded when the players started. Static data was manually uploaded to the platform, with connectors to external sources to feed dynamic data in. The intelligence package was prepared by setting up dashboards containing data feeds, analytics, and forms. The game run for several days, and during this time players would see these dashboards changing as a result of  M. Reis et al. the input of new data, updates to the analysis, and their own inputs via the forms. Players used forms to record their own notes and inputs in the platform, thereby structuring their moves in pre-defined, usable formats. This human-generated content was used as any other content in the platform to convey information on dashboards and be part of analysis. Some of these inputs were used to fill in well-known diagrams, like SWOT analysis, Porter’s five-force models, or BCG matrix (see Figure 7). Part of the game took place with the participants physically located in different regional offices of the com- pany, and the platform could be used as a “meeting point.” Part of the communication between the players and the teams derived from the inputs in the forms, adding yet another level of dynamism to the game. As in a social media environment, team mates could see each other’s comments and inputs, while acting on the insights they were getting both from their colleagues and the data flowing into the platform. The game happened in several phases (moves).At the end of each phase the teams would present actionable insights, which were made visible to other teams, thereby simulating competitive moves. As in any other business war game, the coordinator was responsible to supervise the game flow, using the knowledge sharing features of the platform as the privileged means to interact with the participants. He had ac- cess to the whole information in the platform, being able to view simultaneously every team’s progress (as op- posed to each team, who were only aware of their own information). This way, instead of walking back and forth between rooms, the coordinator actually had a “helicopter view,” and could get better insights in the over- all dynamics of the game, a valuable asset for delivering better conclusions in the end. 4.4. Game Conclusions In the end of all rounds, each team had their own conclusions, insights and foresights laid in dashboards like the one depicted in Figure 8. Figure 6. Markets, teams and players. Figure 7. A BCG matrix filled with inputs from players.  M. Reis et al. Figure 8. Dashboard with conclusions. These dashboards were the actual deliverables each team brought to the game conclusion. The coordinator used them to summarise the outcome of each teams activity, and they were also analysed in detail by the com- pany executives in order to draw actionable insights (actually, the company has subsequently taken decisions based on the outcome of the game). 5. Conclusions Adapting BigPicture to run a business war game was part of a project that intended to bring gamification fea- tures into a business analytics system. For this purpose, the project included the development of collaboration and knowledge sharing, integration with social networks, enhanced usability, blending fictitious data with real market data collected automatically from external sources, and scenario simulation, among others. Before running the war game described above, there were several pilots run on early prototypes of the plat- form, one of them by MBA students playing as beer makers competing in the Angolan market [8]. These ex- periments were important to validate the developments made in the platform, before the first real use-case, de- scribed in this paper. Further developments were made after this, in order to fill functional gaps identified by the players, and a new edition of the game was scheduled for late 2015. From an IT perspective, the resulting platform materialized an innovative product, combining analytics, si mula- tion and collaboration in a single system, with the need to adapt and optimize different architectures in order to come up with a coherent, functional and performant platform. Acknowledgements This research was partially supported by the QREN/PO Alentejo program, under project number ALENT-07- 0202-FEDER-022850. References [1] Luhn, H.P. (1958) A Business Intelligence System. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 2, 314-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1147/rd.24.0314 [2] Sabin, P. (2014) Simulating War: Studying Conflict through Simulation Games. Bloomsbury Publishing Group, Lon- don. [3] Herman, M.L. and Frost, M.D. (2008) Wargaming for Leaders: Strategic Decision Making from the Battlefield to the Boardroom. McGraw Hill, New York. [4] Deterding, S., Khaled, R., Nacke L.E. and Dixon, D. (2011) Gamification: Toward a Definition. CHI 2011 Gamifica-  M. Reis et al. tion Workshop Proceedings, Vancouver, 2011, 12-15. [5] Park, H.J. and Bae, J.H. (2014) Study and Research of Gamification Design. International Journal of Software Engi- neering and Its Applications, 8, 19-28. [6] Gilad, B. (2008) Business War Games: How Large, Small, and New Companies Can Vastly Improve Their Strategies and Outmaneuver the Competition. Career Press, Pompton Plains. [7] Herger, M. (2014) Enterprise Gamification—Engaging People by Letting Them Have Fun. Vol. 1, EGC Media. [8] The Lisbon MBA (2014) The Lisbon MBA Receives First Business WarGame. http://www.thelisbonmba.com/?post_type=press_corner&p=1507

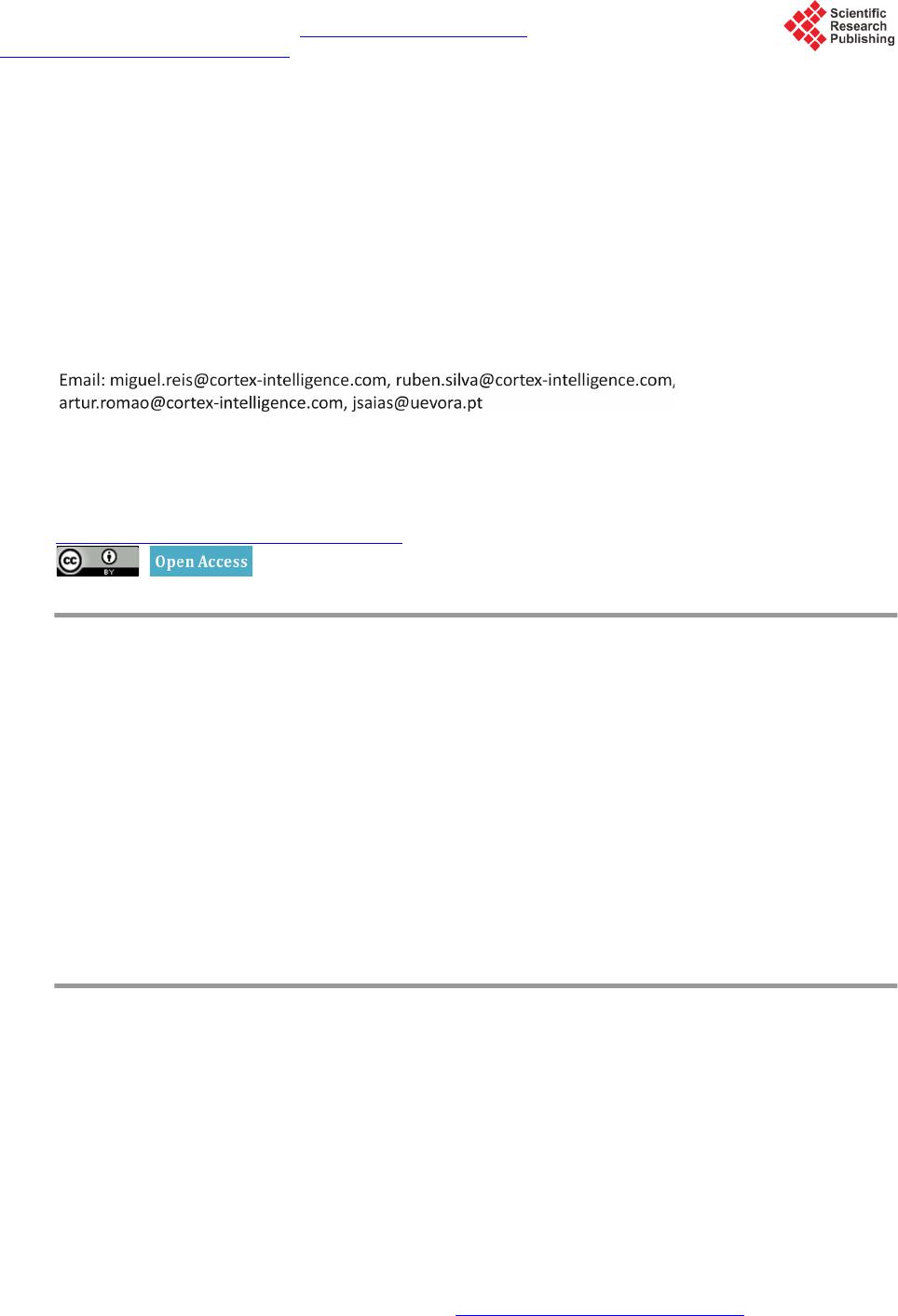

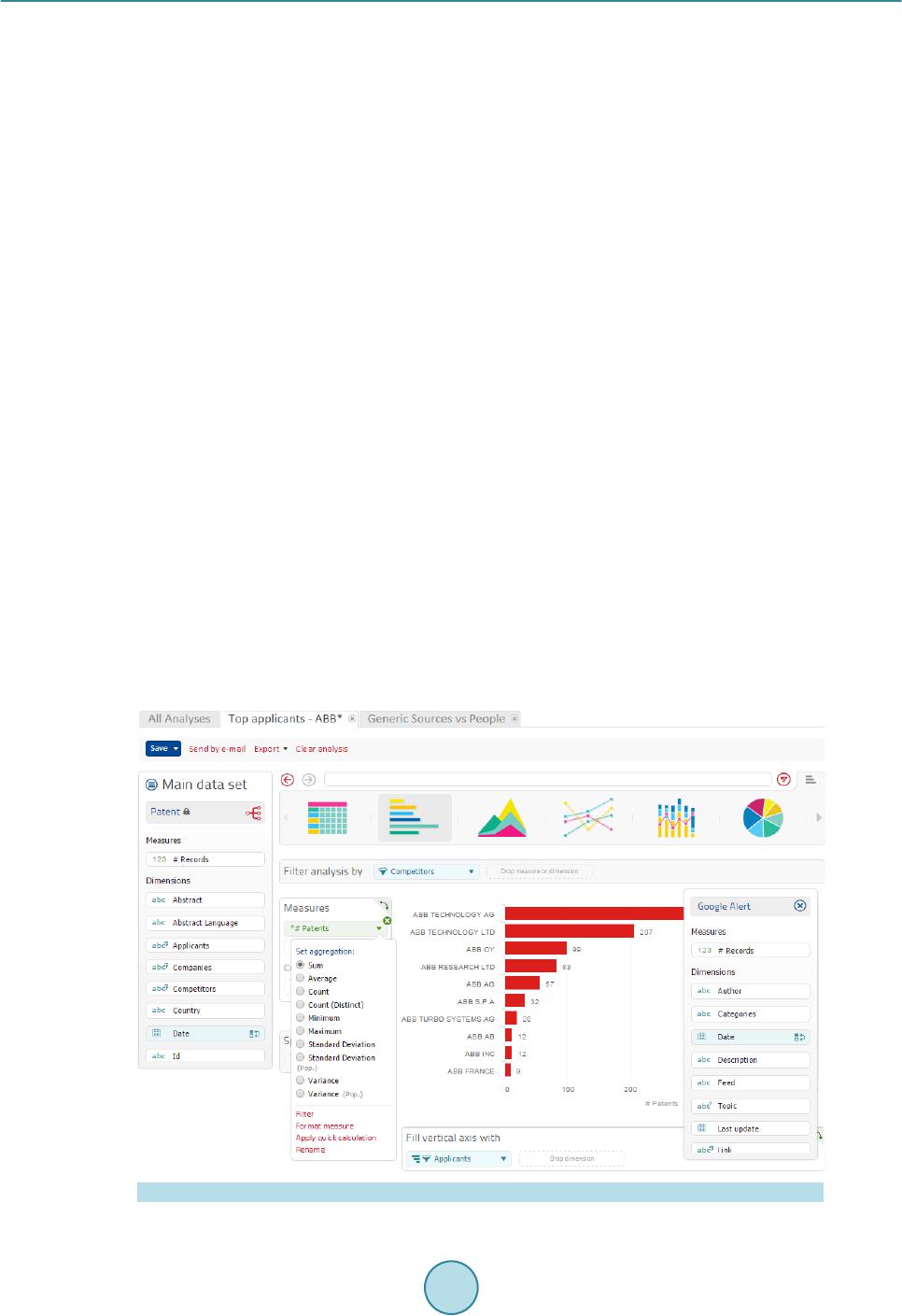

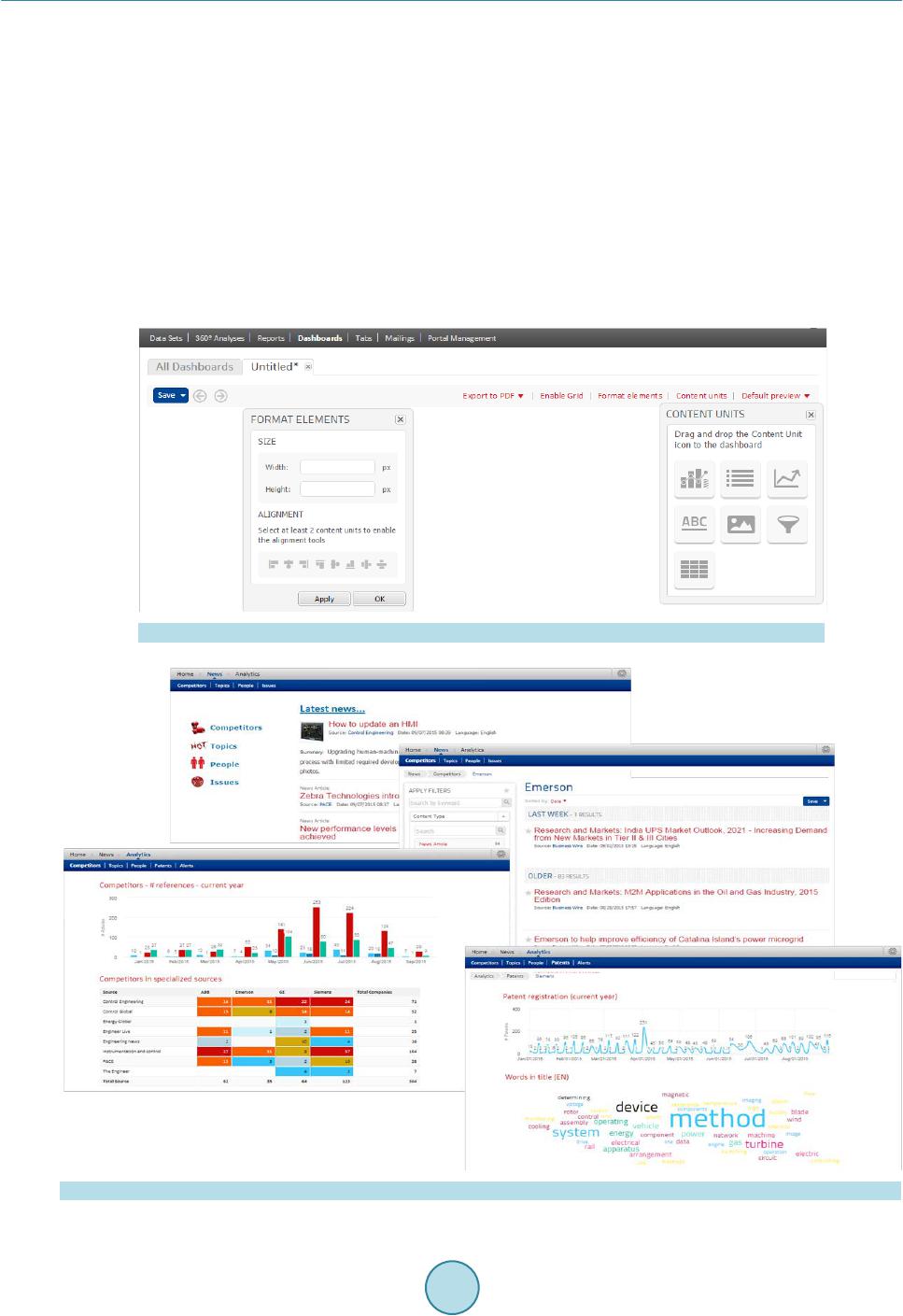

|