Journal of Service Science and Management

Vol.7 No.2(2014), Article ID:45192,21 pages DOI:10.4236/jssm.2014.72010

Portraying the Social Dimensions of Consulting with Structuration Theory

Christian Mauerer, Volker Nissen

Business Information Systems Engineering in Services, University of Technology Ilmenau, Ilmenau, Germany

Email: volker.nissen@tu-ilmenau.de

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 19 January 2014; revised 26 February 2014; accepted 15 March 2014

ABSTRACT

In this paper, we argue that the consultant-client relationship is of central importance for consulting engagements. The paper therefore outlines the social dimensions that are inherent in the consulting system due to its characteristics that create social complexity. To gain further insights into the social interaction scheme and dynamics of consulting projects, a conceptualization based on an appropriate theoretical model is required. We propose to utilize the Structuration Theory for the compilation of the social context of consulting, as this provides a framework for incorporating the social determinants, focuses on actions of human-beings, and additionally allows the identification of interrelated dependencies of structure and actions.

Keywords:Consulting, Consultant-Client-Relationship, Structuration Theory, Consulting Research

1. Introduction

Consulting as a phenomenon of interaction between people in terms of counseling or giving advice has been existing since people live together, why consulting is sometimes called the “oldest profession” [1] . However, for this paper, an orientation on a generic but more purposeful definition of consulting in a business context is required. Consulting in the sense of this contribution is, in accordance to Nissen [2] , defined as a professional service that is provided by one or more persons, who typically have the required expertise to solve the problem at hand and are hierarchically independent of the client organization. The consulting engagement is limited in time, financially compensated and has the objective to define, structure and analyze business issues of the client organization interactively with the client’s employees and to develop corresponding solutions as well as to implement them in close cooperation with the client if requested.

The consulting industry has seen a considerable growth over the last two decades. In Germany, for instance, the total turnover has risen from 12.2 billion Euros in 2003 to 22.3 billion Euros in 2012 [3] . This is likely to continue, as companies are continuously forced to find appropriate organizational and process-oriented answers in an environment of dynamic and ever-changing markets and regulations. To handle those challenges that lead to high management complexity, companies feel urged to use consultants and involve external business-related and methodical expertise [4] . This enabled the consulting industry to institutionalize its business segment of creating, sharing and verifying knowledge [5] . Sociologists consider the increasing weight of the consulting profession as an example of the general shift to service sectors in industrialized economies. Today the consulting industry is recognized as an influential emerging profession to which certain business tasks of an organization are given [6] . Based on its impressive growth the consulting sector gains increasing influence not only on virtually all other branches of industry but also on social and cultural areas [7] [8] .

Though the intensity of interaction between consultant and client differs in the variety of consulting engagements, it is beyond controversy that any consulting engagement requires a certain level of cooperation between consultant and client to solve the problem. Along that point of view Reineke and Hennecke add that the consulting process is basically a meshwork of interactions between the involved human beings that will result in a variety of personal relationships [9] . Consequently, Timel highlights that ability and willingness to cooperate is a critical indicator for professional work for both the client and the consultant [10] [11] .

Thus, consulting should be seen as a complex social activity. The success of consulting strongly depends on the relationship and interactions between consultants and clients within the consulting project [12] . This interaction, however, is not well understood so far. A better understanding of this relationship would offer opportunities to increase the chances of consulting success. On a more general level, we believe that a sound theoretical basis for consulting in the sense of consulting research [2] can help to improve the often rather shirt-sleeved way consulting is conducted today. This would have a positive impact on the client as well as on the consultant side and potentially improve the professions rather damaged reputation.

This motivates our research that aims to provide a social framework for consulting interaction and illustrate the determinants that create social complexity and uncertainty of consulting services. It is intended to enhance the business economic view of consulting services by a sociological perspective. Based on a literature review we first explain the modalities of consulting services in order to outline the theoretical perception of the research object in question. For that purpose the typical activities of consultants are briefly outlined in Section 2, whereby consulting services are characterized as complex social phenomena. In Section 3, the significance of the consultant-client-relationship and the imperative for trust are highlighted in order to grasp understanding about the given inter-dependencies.

It will be argued that for further investigation of the consulting context, an analytical and explanatory theoretical framework is required for making valid statements about the social interaction schemes in consulting. For that purpose, the requirements on the theoretical conception of consultant-client interactions are outlined in Section 4 and the essential theories that have been applied already to the consulting context are briefly recapitulated and evaluated with regard to their explanatory potential. Consequently, the Structuration Theory is proposed to provide substantial insight. After having introduced to the basic principles of Structuration Theory in Section 5, it is illustrated in Section 6 how the consulting system is perceived in the structural modes of signification, domination and legitimation. Finally, in Section 7, some conclusions and reflections on the use of Structuration Theory in this context are given.

2. Consulting Services as Complex Phenomena

The various functions that have been assigned to consultants in the academic literature in context of their engagement have been summarized by Kolbeck as neutrality, knowledge-sharing, efficiency and a legitimization function [13] . With that list however, the functions are illustrated from a self-evident and superficial perspective. The view on the more specific intentions of an organization for engaging a consulting firm reveals a wider set of purposes that do mainly reflect the consultant as an instrument for the organizational game. Beyond the sole use of consultants for solving business issues and gaining creativity, they are frequently engaged from the buyer to demonstrate capacity to act, finding arguments that support a decision that is already taken as well as to displace the responsibility for decisions and failures to the consultancy instance. Therefore, consultants are often used to strengthen the own hierarchical power of the buyer [14] . This indicates already a tough micro-politic terrain in which the consultant needs to act.

Regardless of the different functions behind the consulting engagement, there is a typical set of tasks which consultants carry out during consulting projects. Appelbaum and Steed have consolidated the consultant’s classical activities to the following list, which gives an overview about consultant’s missions and client’s expectations as well indicates the variety of social profiles the consultant must obtain [15] :

1) Providing information to a client 2) Solving a client’s problem 3) Making a diagnosis 4) Making recommendations based on the diagnosis 5) Assisting with implementation of recommended actions 6) Building a consensus and commitment around a corrective action 7) Facilitating client learning 8) Permanently improving organizational effectiveness Despite the various fields of engagement possibilities, there are certain characteristics of consulting services. The nature of consulting is that of a weakly pre-determined and complex domain. Complex systems are basically associated with the attributes of unclear and volatile path developments, various sources of irritations, multiple dimensions of pressure, inherent risk and distributed areas of action [16] .

Consulting services show general convergence with these attributes: the actual consulting service as the product is to be concretised while the consulting processes are carried out based on interactions with the client. The directions on the way to the final consulting result are thereby significantly irritated by several bases of expectations from both the client and consulting organization [17] . Moreover, most of the consulting projects are faced with considerable time pressure that creates additional tenseness [16] . A certain portion of risk is always inherent to consulting projects, too. This originates from the structural input-output uncertainty that is typical for services in general, as those are provided by incorporating external factors of production [18] .

The consulting context is discussed in the academic literature by highlighting four major characteristics [19] . Inseparability means that buyer and seller of a consulting service must interact to refine the consulting process and thus the actual delivery. A high level of interaction intensity is required in combination with relational exchanges whereby the client’s needs are established by the consultant and the consultant’s professional ability and quality are assessed by the client. In the information-exchange process, personal relationships are important to enable creation of implicit interpretations and obligations as well as to develop trust [19] [20] . Intense interaction can also be viewed as the need for overcoming information asymmetries on both sides: the consultant’s uncertainty about the specific form of the client’s demands; and the client’s uncertainty about his choice of the right advisor and the consultant’s approach to solve the client’s issue [19] .

The consulting service is also attributed with intangibility, even at a higher degree compared to most other services. Intangibility means that services do not take the form of a material product. The consulting service cannot be sampled before the purchase and there is no possibility to reproduce any service that has been already delivered in other situations [19] . This comes along with significant difficulty for the client to assess the capabilities of the consultant ex ante and to evaluate the service quality even ex post [21] .

Heterogeneity of consulting services refers to their generally very low level of standardization. Consulting Services usually require the re-tailoring to each client in a process of uniqueness. This again leads to problems of quality control as well as the need for the client to be closely involved in the service creation process to check appropriateness. In that context Clark argues that a large part of the client assessment of appropriateness may depend on client’s impressions of the services delivered by the consultant. In turn, the consultant strives to manage those impressions with trying to sell the consulting work most positively to the client [19] [20] .

A further characteristic is seen in the perishability of the consulting service. This occurs since the creation process for consulting outcomes is dissolved after the consumption and needs to be started by new at another consulting engagement. The consulting result, including some of the intellectual property rights, is transferred from the seller to the buyer and can be utilized by the buyer internally. Although repeat business often occurs, the new consulting engagement will again require new tailoring and will therefore produce new contingencies [19] .

The perception on the role of consultants is currently going through a paradigm shift, as significant cutbacks through consolidated consulting projects, changing client expectations as well as increased demands and pressures on consultants have been recognized. Consultants find themselves challenged to provide a wider range of services than they did in the past, including implementation, and the need to match goals with results. It becomes obvious that the rather perishable facets of consulting services must be made much more tangible, long lasting and highly apparent to the client [22] .

The consulting market is characterized by a high level of intransparency, which causes a high amount of transactions costs to gain a market overview and to identify the best consulting offer for certain demand [23] . The main determinants for consulting competition are experienced-based trust and reputation [24] . As a result consulting is to a big extent driven by repeat business. It is not primarily about winning one single consulting project at a certain client, but steadily doing business with this client. Consequently, consultancies aim for creating a long-lasting and trustworthy network of client relations, which will be the major fundament for their growth, competitiveness and market success [24] .

3. Significance of the Consultant-Client Relationship and Imperative of Trust

Irrespective to the actual role of the consultant, whether he acts more as a coach or a supervisor or as an expert, the consulting situation is always determined by the clash of two parties with different interests. The client has the demand to find efficient support for solving his specific problems, whereas the consultancy acts as supplier for a profit-driven service. The relationship between client and consultant is therefore attributed with the respective expectations, restrictions, negotiations and agreements [25] . Generally, consulting can be considered as a socially and culturally contextualized business.

From a system-theoretic perspective, the actual consulting event, determined by the single steps of actual consulting processes, is embedded in a framework of certain social patterns [26] . In the way the client and consulting organizations develop patterned ways of behaving in their respective proprietary systems, the same applies for the consulting system: both consultants and clients develop certain patterns of dealing with each other. While the consultant and client interact, the consultant-client nexus becomes its own system that is subject to the same system realities as any other. The emerging logic of the consulting system infuses the consultant-client relationship reciprocally. With modeling a system-theoretic intervention by the consultant in the client organization, this basically reveals a fundamental dilemma in the mode of conduct: the client system attains to the outside of their boundary to seek for consulting support. Reversely, the engagement of consultants constitutes the creation of a new consulting system, which could restrain the consultant’s access to the client organization as well as his external objectivity [27] .

The building of the consulting system reflects further general social system characteristics with typical rituals and themes. In the early phases of the consulting system, Gemmill and Wynkoop describe that both consultant and client have a mask, meaning that there is a portion of themselves which they consciously try to keep secrete. A psychodynamic observation shows the frequent existence of a high level of resistance and hostility on both sides toward the other group, with sometimes even casting the others into the group of enemy. A given high degree of resistance and hostility on the client side leads to identification problems of the consultant and discourages him to proactively diminish these social barriers. Defensive response by the consultant could be a result, which will in turn have a destructive effect on the continuing of the consulting processes [28] . Moreover, in the way of forming the consulting system the consultant and client need to deal with the allocation process for power and trust relations. The group of consulting participants, therefore, experiences several stages of crisis and different emotional states. So, a further important step is to learn when to take on social conflicts and how to solve them [29] .

The consulting interactions can be further-on perceived as processes of negotiation and exchange. Exemplarily, the consultant in the role as initiator expresses recommendations, which the client can then decide about whether and how they should be implemented. In this regard, power is considered as the platform that determines what flows into the interactions and how it is adopted [30] . At first the buyer has the power to select an appropriate consultant and to assign him a respective role [31] . During the consulting project there is high risk of power conflicts that arise as power is associated with expertise and experience. Consequently, status claims start to exist as soon as multiple parties interact in the consulting system. Hereby, power can be expressed with setting directives or demonstrating resistance [32] .

The inherent complexity in the consulting system is seen to be significantly reduced when social capital is created [33] . Social capital is defined by Leana and van Buren as “…collective goal orientation and shared trust, which create value by facilitating successful collective action” [34] . The social capital of a consulting project consists of obligations and expectations concerning the accomplishments of the project mission and reflects the capability of the project members to learn and innovate. Consequently, the social framework with causal ambiguities, adverse interests, conflicts and legitimacy issues needs to be in focus for forming a functioning consulting system (compare to approach of Sydow and Staber [35] in a different context).

Consequently, the interactions between consultants and clients and, hence, the focus on individuals are the crucial drivers for consulting success. Constant communication is required ensuring that the specific context of the client organization can be incorporated into the development and implementation of solutions [4] . Consulting is thus, to a large extent, about forming relationships. The consulting processes are considered to be effective when the consultant was able to build a productive and sustainable relationship with the individuals of the client’s company [12] .

As immateriality, impossibility of preceding performance assurance, unspecified services and high interactivity are constitutive features of supplying business services in general, trust is highly meaningful, especially in this economic segment [36] . Consulting is often characterized as a trust object, since the client needs to rely on the expertise promised by the consultants in advance of the project and the consultant’s performance is also difficult to be evaluated even after finishing the project [11] [37] [38] . The client generally has a twofold attitude towards the consultant: enabling the consultant to act as an advisor and having impact on the client organization. Therefore, a respective level of personal proximity is to be admitted by the client if the consulting engagement is to provide meaningful, purpose-oriented results. In contrast, the consultant’s own economic interest to maximize profit through the engagement and the hazard of opportunistic behavior indicate the need for caution and control. The client is therefore faced with critical attribution problems of what level of freedom can be granted to the consultant [39] . These problems are not controlled by a superior instance; as the consulting industry is not a traditionally regulated profession.

4. Requirements on the Theoretical Conception of Consultant-Client Interactions

As outlined in the previous sections, various social challenges must be overcome to achieve the desired consulting result. While the consultants and clients produce the consulting result via their interactions, they need to deal with emerging social dynamics.

As the characteristics and facets of the consulting system vary in occurrence and intensity from project to project and observations from single projects are unlikely to have equal meaning for another project, an abstraction via a theoretical model gains relevancy. A theoretical model in that context should deliver explanations why both the client and the consultant show the respective behavior in the consulting project. It should allow to conceptually reconstruct the interaction processes, should provide a comprehension of interaction patterns and deliver implications for a subsequent state of the relationship between consultant and client.

For the theoretical reconstruction, however, a sole descriptive portray does not appear to be sufficient, but an explanatory model is required which needs to incorporate the fundamental influencing factors that have effect on the social scheme of the consultant-client relationship. One should focus on motives why the participants of the consulting processes carry out their respective actions and what the intended and non-intended social consequences are. The perspective on the consultant’s and client’s intentions will allow reconstructing their behavior in a mode of ex post interpretation of rationality.

The action scheme of the consultant and the client shows a process of change and progress. Consequently, the social pattern of the consulting system cannot be grasped by constant parameters. A static orientation of the theoretical approach ignores the dynamic action scheme within the consulting system (compare to approach of Iding [40] ). There is also the need to put attention to the irrational processes and unconscious dynamics that influence the behavior of those engaged in the consulting project [27] .

Moreover, the basic constitution of consulting projects is to be understood as a temporary system. Its characteristics need to be interpreted in a system-related perspective, whereby the perception of the embeddedness of that consulting system into the superordinated systems is of great importance [41] . A multi-level orientation is required for the theoretical conception, since the layers of affiliations, environments, interactions and identities need to receive attention for a comprehensive perception of the social scheme of the consulting system (compare to approach of Lamb [42] ).

Having outlined the requirements resulting from the social complexity and dynamics of the consulting system, it needs to be briefly evaluated to what extent the major existing theoretic streams are appropriate for portraying those social dimensions. For that purpose a segmentation of theoretic streams will be used with the following grouping (similar approach of Hasenzagl [43] ):

1) basis theory, 2) subject theory and 3) practice models.

On the level of base theories it has been mainly referred to the systems theory of Luhmann [44] (see exemplarily [11] [45] [46] ) and the theory of neo-institutional economics of Williamson [47] (see exemplarily [48] -[50] ). The systems theory models abstract findings on the behavior and development of systems [51] . In the context of consulting research it gained particular relevancy in the systemic consulting approach [2] . This approach considers the client organization as a system that cannot be influenced externally in a direct way; therefore the consultant is reduced to the role of an observer [52] . The social sphere of individuals has a subordinated role [53] . Consequently the systems theory does not appear to provide a theoretical platform for analyzing the social interactions between the consultant and client.

The theory of neo-institutional economics is based on the assumption that individuals strive to maximize their economic benefits in incomplete real market situations, which are determined by cognitive limits, incomplete information and difficulties in monitoring and enforcing agreements. Concepts developed in this context focus on information asymmetries and opportunistic behavior between economic transactions partners [51] [54] . In this theoretical framework, the model of transaction costs appears to have relevancy for providing explanation about the social interaction scheme of the consulting system, as this model is action-oriented and has been applied in several studies focusing on the consultant-client relationship (e.g. [6] [55] ). In verifying its appropriateness, however, it becomes evident that the transaction cost model does not provide an adequate perspective on the specific sociological layers and elements that are required for explaining the social patterns of interactions. It bases on a sole opportunistic orientation of the actors and has a reduced view on the integration of various socio-analytical levels, specifically the interrelation of systems, actions and individuals [56] .

Also the Structuration Theory is to be grouped into the section of base theories. This theory has not yet been applied to the context of interactions between client and consultant. The only noteworthy link of the Structuration Theory to consulting research in general has been provided by Schwarz [57] when using that theory to provide an understanding about the social terrain of the client organization for enhancing the effectiveness of consulting interventions. The Structuration Theory proclaims the duality of structure and action and, therefore, combines functionalistic and individualistic theoretical approaches. This theory is directly based on the social processes and emphasizes the significance of humans [58] . Consequently, the relevance of the Structuration Theory for the consulting system will be highlighted in the subsequent chapters.

The theoretical models in the segment of subject theories aim at creating a subject-specific comprehension of the research artifact. Subject models are not directly driven by any superordinated theoretical direction. In the context of the consultant-client interactions two specific models have evolved in the academic literature: the client-expert model [59] -[61] and the model of symbolic interaction [20] [62] .

In the expert model, the consultant acts as an expert, identifies a client’s problem and transfers knowledge “…while remaining an objective and neutral advocate of best practice” [63] . This model considers consulting as a unidirectional gathering process of information rather than as a real interaction [64] .

The model of symbolic interactions, also known as the critical model, regards the consultant as the provider of institutionalized myths and rhetorician [62] . It mainly examines the process of knowledge creation within the consulting processes. Hereby, it states that consulting knowledge is developed in interaction with the client and is ambiguous as well as symbolic. Images, stories and symbols serve as “rationality-surrogates” and constitute consultant’s real expertise [64] . It is argued that both models stress single features of the client-consultant interaction, but they do not recognize its multidimensional and complex character [65] . They are thus not assumed to provide a comprehensive and analytical perspective on the consultant-client interactions.

Finally, practice models mainly originate from observations of various situations in the consultant-client interactions, partly supported by empirical methods. Examples in the literature are Maister et al. [66] and Cope [67] . They mainly have a descriptive approach with capturing the specific context of the focused situations. However, they do not allow deriving valid statements or providing proper explanation on a generalized level about the interrelations and intentions that initiate and shape social actions within the consulting system.

5. Applicability and Basic Principles of Structuration Theory

As was highlighted above, a high level of social complexity is a characteristic feature of consulting. Issues of social legitimacy, tacit knowledge, micro-political interaction schemes, sense-making processes as well as the resource and path dependencies along with general interest conflicts have to be considered when examining the consultant-client interactions.

In this research work, the application of the explanatory framework of the Structuration Theory for the analysis of the social dimensions of the consulting system is proposed, as it integrates the required multi-level, processual and dynamic perspectives of the consulting system and focuses on both the interactions of the individual and collective actors. As the actions of human-beings cannot be described with fixed rules, the Structuration Theory provides interpretations schemes for social practices.

Referring not only to the economic context but also to the social dependencies within consulting projects can help to better overcome inefficiencies in consulting projects. Structuration Theory is expected to allow for the integration of essential success factors from a social context. As the focus on human actions is emphasized, this theory looks behind the conscious and unconscious intentions of consultant’s and client’s actions and abstracts how the consultant and client build their joint structures. Consequently, Structuration Theory can act as an analytical platform for doing a focused analysis on social facets, such as the investigation of trust between consultant and client.

The theory of structuration has been proposed by Anthony Giddens (1984) in The Constitution of Society [68] . Giddens basically argues that actors (described as human agents) and social structure (rules and resources) are interrelated. Structure is thereby reproduced by repeated actions of individual agents taking place within a structured framework [69] .

This constrasts with the deterministic perspective on structure of others in the literature which assumes that structure is impervious to human agency [70] . It informs and constrains the activities of actors instead of being recursively created and recreated by the actions of human agents. Determinists believe that only past and present determine the level to which humans have an influence over their future. Giddens rejects the determinist view with arguing that human beings should be able to identify laws that will predict how societies will develop [69] . Consequently, Structuration Theory aims to avoid the extremes of a strict determinism through structure or agent. Instead Giddens aims to balance both structure and agent.

Social structures are created and shaped as a result of the recursive interactions between institutional structures and individual actions. Giddens states that structures are “both the medium and the outcome of the practices which constitute social systems.” [71] . Giddens’ defines structure as a set of rules and resources, recursively implicated in the reproduction of social systems. Structure exists only as memory traces, the organic basis of human knowledgeability, and as instantiated in action [68] . In Gidden’s view, structure is constituted by rules and resources, which are both governing and available to individuals.

Giddens has identified three types of structures in social systems: signification, legitimation and domination. Signification creates structure with producing meaning through organized webs of language, which could be semantic codes, interpretive schemes or discursive practices. Legitimation produces a moral order via immersion in societal norms, values and standards and therefore serves as code of conduct. Domination produces power and is at the same time an exercise of power, which originates from the control of resources. These structures are interrelated and create and reinforce our complex social reality [69] .

From the Structuration Theory perspective, rules are techniques or generalizable procedures applied in the production or reproduction of social practices. This definition refers to communication codes and linguistic rules, valid organizational norms, technical directives and other rules drawn upon in social interactions. With regard to their appearance, rules can be codified and articulated as a policy and bureaucratic rules, but can also exist as unarticulated background knowledge such as rules of interpretations. Resources signify capacities to create command over material and social objects with generating power. Resources refer to the capacity to affect material objects and means (allocative resources), as well as nonmaterial capacities to harness the activities of other individuals (authoritative resources) [69] .

As Structuration Theory has its focus on the doing and being of the individuals that carry out social interaction, the concept and role of the actor (as agent) needs to be illustrated in more detail. Giddens states that individuals are knowledgeable. This implies that people know what they are doing and how to do it. It also means that people are capable of using their knowledge to act in creative and innovative ways, and consequently transform the structures (rules and resources) within they work [69] . The knowledge of rules refers to the ability to apply them in unfamiliar circumstances, as opposed to simply have relevancy in routine circumstances. As a consequence, agents have control over their social relations and can influence those in some extent. The agent then has the ability to rearrange, apply and extend rules to new environments [70] .

Therefore, agency refers to the volitional character of human actions, meaning the capability of individuals to act with conscious intention [68] . Consciousness implies that human beings can and do monitor the domains of social actions within which they operate. They particularly monitor their own actions and their consequences, the actions of others and also other environmental aspects. This ability for monitoring the domain of action bases on two levels of consciousness: practical and discursive. Practical consciousness is the capability to maintain a continuing theoretical understanding of the grounds of their social activity. Human agency thus exhibits what Giddens calls the rationalization of action. Usually, people know more as what they can say [69] . Discursive consciousness, on the other hand, is reflexive, focusing on the “monitoring of that monitoring of action”. Discursive consciousness is the capability to explicitly describe intentions that determine actions as well as the reasons and motivation for action. These two levels of consciousness are steered by motivations located in the unconscious of agents that aims to find psychological security. This need can explain by a big extent why agents routinely reproduce social structures that they even interpret as excessive bondage [69] .

To determine how agents interact, Giddens uses the analytical distinction between the three types of social structure: signification, domination and legitimation. These structures are built up by the structural properties of norms, sanctions, communication, and interpretative schemes. However, Giddens points out that in any concrete situation of interaction [e.g., such as in an organization], actors make use of these structures and structural properties as an integrated set and not as separate structural units [69] .

The signification structure is linked to organizational interaction by different kinds of interpretative schemes. These schemes are the cognitive means by which actors makes sense of what others say and do and are one of the modalities of structuration [69] . Therefore the signification structure could be used by agents for communication and understanding and, in the long run, to provide some sort of meaning for different types of activity [72] . The modalities work as a catalyst between the overarching social structure and the day-to-day activities of an organization. As Giddens puts it: “What I call the modalities of structuration serve to clarify the main dimension of the duality of structure in interaction, relating the knowledgeable capacities of agents to structural features.” [68] .

The domination structure deals with various ways of exercising power using different types of resources. Power is divided into two classes. In the broad sense it refers to the transformative capacity of human action. In the narrow sense it refers to the medium for domination. In its broader sense power can be related to the ability to get things done, i.e. create activity. In the narrower sense, power is simply domination through, for example, an organisational hierarchy. According to Giddens, all social relations involve power in both the broad and narrow sense [68] . In specific time-space locations the capacity to exercise power can be related to asymmetries in the distribution of resources [73] . Both allocative and authoritative types of resources facilitate the transformative capacity of human action while at the same time providing the medium for domination [69] .

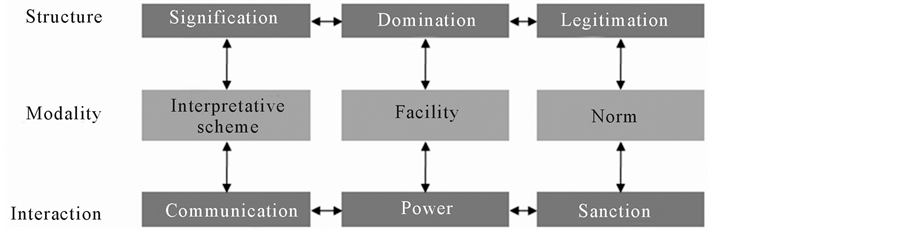

Giddens further states that the legitimation structure involves the moral constitution of interaction and is mediated through norms and moral codes which sanction particular behaviours. It comprises the shared sets of values and ideals about what is regarded as important and what is to be regarded as trivial. Figure 1 depicts the interconnected dimensions of Gidden’s duality of structure.

The interaction between the three modalities occurs simultaneously and is only separated at an analytical level. Through the interplay of these modalities (the process of structuration) human actors reproduce or (less frequently) change existing norms of behavior [74] . The key principle in Structuration Theory is the duality of structure

Figure 1. Dimensions of structural duality ([69], p. 29).

structure: human action is enabled and constrained by structure, but structure results from human action. Structure is thus both the medium and outcome of action that it recursively organized. The duality of structure in interaction can be understood as follows: Agents exercise power, communicate and sanction their own behavior and those of others by referring on modalities (stocks of knowledge, rules and resources), and in doing so produce and reproduce structures of signification, domination and legitimation [69] .

The connection between social structure and human action refers to the process of structuration, the process by which the duality of structure evolves and is reproduced over time space [69] . This process is executed by three modalities: interpretive schemes, resources, and norms. Interpretive schemes are standardized and shared stocks of knowledge which humans reflect with interpreting behavior and events, and hence achieve meaningful interaction. Actors draw upon interpretive schemes that are mediated by communication. This does not only enable or limit communication, but with perceiving it in interpretive schemes, actors reproduce structures of signification. Resources are the medium by which intentions are realized, goals are achieved and power is exercised. Finally, norms are described as rules governing sanctioned or appropriate conduct, and they define the legitimacy of interaction within an order of moral setting. Norms thus enable and constrain action. With their invocation in interaction, actors create structures of legitimation [69] . These three modalities define how the institutional settings of social systems influence deliberate human action by affecting the manner how people communicate, enact power, and determine what behaviors to sanction and reward. They also determine how human action form social structures when the structured social practices are institutionalized [69] .

Within society and within organizations there are discrete social systems of interaction. Examples of these within the general community might include religious groups and political parties. At the workplace discrete groups might include work units, for example the research and development unit or the marketing unit, and other groups such as the staff social club. Each of these systems works in its own individual way. Giddens described such systems as “The patterning of social relations across time-space, understood as reproduced practices. Social systems should be regarded as widely variable in terms of the degree of “systemness” they display and rarely have the sort of internal unity which may be found in physical and biological systems” [68] .

6. Perceiving Consulting Services with the Modes of Structuration Theory

6.1. Overview

As the consulting project is embedded in multiple contexts there are structural conditions that influence how the consulting project is organized. Since each consulting project is a unique system, however, projects are to some extent independent from their environments and developed in idiosyncratic ways as a temporary social system. At the same time the consulting project as an own system relies on routines, norms and practices that are established in various systemic contexts and that both facilitate and constrain system organizing activities (compare to Manning [41] ). Social systems, such as temporary consulting projects and their social contexts, are brought about by social practices of the consultant and the client through regularized activities based on which the actors apply (and reproduce) sets of symbolic and normative rules as well as allocative and authoritative resources. Consulting systems have “systemic boundaries” since structural properties can be identified that guide the actions in terms of specific (systemic) sets of rules and resources of the consulting project. With entering the consulting project both the consultants and the clients take up roles. The process of entering the project also comes along with uncertainty and risk. Both create anxiety for the parties. This anxiety results from the situation that both parties enter into new personal relationships, receive new tasks and deal with new routines [27] . The Structuration Theory hereby focuses on the recursive interplay of actions and structure and therefore provides insight how the relationship between the consultant and the client is constituted and embedded in a temporary social system.

A consulting project can usually not be considered as a closed circle of isolated activities, but is integrated in a system of social relationships towards the client organization and the consulting organization. Those have significant impact on the constitution of the consulting system, even though the project organization for the consulting processes has a distinct social identity and organizational culture. The consulting project, therefore, creates social capital that encompasses obligations and expectations with regard to the goals and activities, as well as reflects the capability of the project members to generate knowledge and innovation. On the other side, strained social relations can also create negative outcome in terms of stagnation and frustration. Consequently, the consultant and the client are not only faced with challenges of delivering expected project outcomes based on applying methods of technical nature (like focusing of working results, budget and plans), they also have to cope with causal ambiguities, interests, conflicts and legitimacy issues that are typical for social relationships. The consultant and the client are also exposed to the usual social group building process and have to create the structures of the consulting system with engaging in power and trust. The consulting project passes through several phases of crises in order to become a matured group. In that context the consulting system also learns how to cope with conflicts and uncertainties to become more and more an independent unity that can increasingly act on their own authority [29] .

The [re-]produced structures of domination, signification and legitimation of the consulting system provide the context for developing the respective portion of trust, commitment and reciprocity norms, which enable the coordination of the consulting project. Based on both the temporary character of the consulting project as well as the strong binding towards the client organization due to the mission of solving its problem, it is expected that a consulting project is only able to produce a limited scope and intensity of structural institutions on itself. There is a strong relation to the organizational scheme of the client organization, which enables inter-organizational actions, pronounces normative expectations and, consequently, provides the social context that constitutes signification in terms of meaning for the consulting project (compare to Sydow and Staber [35] ).

6.2. Signification by Communication: Meaning and Sense-Making in Consulting

Signification describes the rules how meaning is constructed for the interactions between the consultant and the client. As signification refers to the cognitive order of a social system, it also includes the interpretation and perception by the consultant and client of how the consulting system works. As in other social systems, the agents of the consulting project interact with each other on the basis of their conscious or unconscious interpretative scheme, which can be individual perceptions of rules of order, missions or experienced sense-making logic. For the consultant and the client, it is vitally important to refer to those interpretative schemes in order to enable interactions during the consulting process and, as a result, produce enabling structures for the consulting system on its own.

On the client side the interpretative scheme is to be portrayed with contrasting it to the expectations that the client has with regard to the consulting engagement and the consulting project. Ojasalo has classified the expectations of the client into fuzzy expectations, implicit expectations as well as those that are unrealistic. Fuzzy expectations refer to the indefinite idea about the outcome of the consulting project. Ojasalo argued that clients do usually not have a precise idea of how the solution to be proposed by the consulting project should look and what the change in the client organization should be [75] . Also, what the client really wants is not necessarily what they actually say. Despite the fact that the client usually does not exactly know what he wants, he is regularly assumed to know what he does not want [76] [77] . Implicit expectations of the client as the second form are elements of the consulting service that are so self-evident that the client does not actively think about them, also not with regard to the potential that they do not materialize. Next to this, the client also bears a certain portion of unrealistic expectations, which describe those expectations that the consultant can hardly resolve due to the circumstances of the consulting situation and for which the consultant cannot be held responsible if they cannot be met [76] [77] .

Abstracting these expectations towards the consultancy engagement to the higher level of the overall client organization, meanings and, therefore, signification structure is created with assuming the consultant to act as a trigger for thoughts that are present in the organization’s life, but have not been expressed before. These are described as “un-thought known”, which are inchoate and pre-conscious in everyone’s thinking, but not acknowledged publicly in the client organization. The consultant is then expected to deal with these unexplored matters that are inherently present within the organizational system [27] [78] . Next to this, several aspects of consulting engagement motives can be summarized to the general intention of strengthening control of individuals within the client organization. This has particular meaning for the management level of the client company. Consulting projects are seen as mechanism to stabilize or enhance the individual control capacities with providing (new) information about external best practices or about the client organization itself to the client managers, which has not been available so far in structured form or no assessment has been done on them. This is why already information from the analysis phase of the consulting project is often perceived as valuable within the client organization, as this can provide new insights and strengthens the control capacity [79] .

With considering signification structure as interpretative scheme from the consultant side, meaning for the consultants interactions during the consulting projects are constituted by the portion of acceptance and credibility he receives from the client during his engagement. The consultant is viewed as operating in a different arena in relation to his clients. Consequently his role and value is intimately tied-up with his ability to translate his knowledge and understanding of this outer context to his client [80] . Acceptance and credibility are crucial to enable effective intervention by the consultant in the client organization, which is essential for providing meaning to the consultant’s role [81] . The social dimensions of acceptance or rejection as well as credibility in the consultant-client relationship, therefore, have great significance. Acceptance enables the consultant entering the power structures of the client’s company and gaining the legitimization to influence the processes of the client with the consulting project. Acceptance helps the consultant to achieve the appropriate level of authority. His role then changes from solely being a supplier to being an autonomous actor. An accepted social position increases the possibility that clients adopt the findings and analysis results of the consultant [39]. The matter of credibility is best understood in conjunction with the functions and roles the consultant is supposed to assume, since credibility pertains to specific sets of behaviors, interactions and circumstances. Consultants have different degrees of credibility in their various roles, relationships and situations. The manner of how the client attributes credibility to the consultant, and consequently how signification structure is created within the consulting system in that regard, is, therefore, dependent to the conscious or unconscious expectations towards the consultant, whether primarily providing information, diagnosing problems, applying specialized expertise, facilitating, solving problems or implementing solutions is in focus of the client’s expectation [82] .

As indicated above, signification structure of the consulting system is produced with creating meaning based on the client’s expectations and the attribution of acceptance and credibility to the consultant. This production of significance is done by human action of communication. Giddens argued that communication involves the utilization of shared interpretative schemes, which are stocks of knowledge that human actors use to make sense of their communicative actions. This type of knowledge mediates the production and reproduction of signification [69] [83] . Clegg noted that “consulting is first and foremost a linguistic activity—a discursive practice through which realities are enacted” [84] . In the framework of the Structuration Theory communication can be regarded as cooperative practice referring to specific rule or resource sets that are produced jointly and reproduced through shared, recurrent social and economic interactions among individuals [69] .

Cooperative practices are formed by shared purposive activities between the consultant and the client. This also requires the presence of consultation willingness of the client. The actual consulting service as the product is to be concretized while the consulting processes are carried out based on cooperation between consultant and client [17] . The social atmosphere between client and consultant forms the basis for effective communication. Communication plays an important role during the consulting process in the sense of integration, information gathering, transparency, debating and decision-making functions [85] . As there are many activities the consultant cannot carry out properly on his own if the client’s employee is reluctant to collaborate, it is vital that a high level of client’s involvement is given, possibly via allocated responsibility for certain tasks. This will promote client’s identification with the results and his readiness for collaboration. To enable cooperative work, relationships among the client and the consultant are formed by signaling readiness to act and deliberate discursive action. The characteristic of agency included in the Structuration Theory also has implications for the analysis of cooperative work. An important implication is that cooperative work practices of the consultant can have significant effect to meet the client’s unconscious needs for ontological security expressed on the unconscious level, which is inherent in the consulting processes due to the transactional and institutional uncertainty of consulting services. Collaborative work practices can help to maintain social identity of the client’s employees, promote meaningful social interactions and develop self-esteem and psychological security. On the level of practical consciousness cooperative work provides rationalizations to the client and facilitates information sharing between client and consultant. At the discursive level, the cooperative practices promote both consultant’s and client’s capabilities to refine, discuss, and evaluate cooperative practices in order to involve them into the project outcome (compare to approach of Lyytinen and Ngwenyama [83] ).

Communication as an interaction scheme of the Structuration Theory also focuses on knowledge creation and learning, both as two elementary components of most consulting projects. Even though projects have the character of a temporary system they have to be perceived as being embedded in a more durable set of contexts that survive the project and serve as knowledge and learning repositories. It needs to be emphasized that the clients and the consultants are knowledgeable and purposeful in their actions. They are capable to provide a rationale for their actions through their reflexive monitoring of the project based interactions. It is assumed that consultant and client may influence the learning contexts of their project-based interactions without fully controlling these contexts. Thus, each learning context is a contested terrain in which reciprocal influence between consultant and client exists (compare to approach of DeFillippi and Arthur [86] ).

6.3. Domination Exercised by Power: Actionability in Consulting

The Structuration Theory argues that the capability of an agent to draw on power resources is related to domination at the level of structure [69] . Giddens identified two types of resources of power: command over allocative resources (objects, goods and other material phenomena) and authoritative resources (the capability to organize and coordinate the activities of social actors).

Giddens highlighted the transformative capacity of human action, which may be a positive outcome, relational power or domination, involving reproduced relations of autonomy and dependence in social interaction that have negative connotations [69] [87] . Macintosh argued that power in the broader perception is the ability to get things done, while power in the narrow perception is simply domination. All social relations involve power in both perceptions, but the exercise of power does not occur in one direction only. Power can be exercised by both superiors and subordinates. He highlighted with discussing the “dialectic of control” that all social relations involve both autonomy and dependence. Normally, power flows smoothly and its effects remain widely unnoticed. However, conflicts are supposed to expose power. In that conjunction it is important to summarize the view on power with highlighting that power on the one hand works to control individual actions and to gain cooperation, but it also works on the other hand to free action [69] [87] .

As a result of that, the domination structure for the consultant in the consulting project describes his capacity to act during the consulting process and, therefore, what influence he has in guiding the consulting project, identifying and determining the solution and outcome of the project, and, consequently, to what extent the consultant can impact the client organization. This playing field of the consultant is foremost determined by the consultant’s role, which outlines his potential for giving directives towards the client within the bounds of the consulting project, and, thus, the intensity of domination he obtains. This can also be described with consulting intensity. Within the boundaries of the consultant’s role, his domination potential is driven by his expertise of knowledge and methodical skills, his personality characterized by charisma and appearance, his assertiveness and convincibility. According to von Rosenstiel, the actual domination structure is concretized by the level of sanctioning potential the agent has. This can be the reward potential on the one hand, with honoring a desired behavior of loyalty. On the other hand, this also refers to the escalation potential of threatening somebody with punishment [88] .

Based on that, the domination structure of the consultant during the consulting process is to be described as relatively weak on an initial view. The consultant does normally not obtain a formalized decision power, but acts as a “supporter” for a certain time-frame. Despite the fact that the domination of the consultant is relatively higher the higher the management level of “the buyer” in the client organization is, the domination of the consultant however remains in strong dependency to the domination of this buyer. Consequently, the domination structure is an important social facet that is to be developed during the consulting process based on the recursive practices of the consultant in interactions with the client. The consultant has to engage his expertise in knowledge and methodical skills in an appropriate way to build capacity to act. He steadily has to bring adequate personal skills to achieve a status on which he is able to convince and on which he can assert the matters of the consulting project within the terrain of the consulting project.

The domination structure of consulting projects is also characterized by the given authoritative and allocative resources of the client organization. Here, the client’s hierarchical structure and power bases play an important role. The consulting system is impacted by client’s political landscape. Here, the main players are the sponsor (who normally acts as supporter for the consulting project), the receiving managers as acceptors for the consulting outcome as well as other interested parties or constituencies with different agendas and with the potential of opposition. The political climate can change over time as the domination structure of the client organization matures through the created dynamics from the consulting project. The strengths of potential coalitions and ways to develop relationships to negotiate or arrange trade-offs to gain support or decrease opposition are essential for the domination structure [89] .

Next to this, domination structure for the client-consultant relationship also has significance with regard to the change impact to the allocative resources of the client organization. This concerns e.g. shifts of processual or institutional ownerships as an outcome of the consulting project. Hereby, power positions within the client organization can change as outcome of the consulting project and power relations are to be renegotiated, which comes along with production and transformation of discursive practices under conditions of novelty and ambiguity. Moreover, agents marginalized in their own organization may have the potential to exercise power discursively even when they do not have the apparent domination on the initial view. In the concrete consulting situation they can produce resistance with dispensing their expertise or personal engagement and, thus, limiting the effective implementation of the consulting outcome.

According to the Structuration Theory, power is inherent in structures and is applied on the interaction level between the agents. However, power is considered not to be simply oppressive or in the hands of elites and leaders [69] . Therefore, substantial power positions can also be held by client’s employees on a lower level. As a result, power always needs to be incorporated in any analysis of social interactions between the client and the consultant. Power is not to be conceptualized as an unwanted effect or as an obstacle to change, but as a normal characteristic of the consulting system. Power-relationships are part and parcel of organizational life. It is particularly important to pay attention to power in situations of organizational change projects, when the re-allocation of resources is on the agenda [60] [90] . In Giddens Structuration Theory, power has, therefore, two different perspectives: the perspective of an action of the actor and the perspective of the structural aspect. Power is, then, the ability to make changes to behavior and control, or to create domination from an institutional perspective [69] [91] .

But power positions have also relevancy in the context of consulting projects when the consulting system is concerned with micro-politic games, as production and transformation of discursive practices may shift power positions within the client organization. Moreover, client agents marginalized in their own organizations may have opportunities to try to exercise power discursively even when they do not have the apparent capacity in term of hierarchical authority, expert credentials, or economic resources to do so. To the extent that others accept their attempts, power relations may be shifted [32] .

The consulting interactions can further-on be perceived as processes of negotiation and exchange. Exemplarily, the consultant in the role as initiator expresses recommendations about which the client can then decide whether and how they should be implemented. In this regard power is considered as the platform that determines what flows into the interactions and how it is adopted [30] . At first the buyer has the power to select an appropriate consultant and to assign him a respective role [92] . During the consulting project there is a high risk of power conflicts that arise on the fact that power is frequently associated with expertise and experience. Consequently, status claims exist as soon as multiple parties interact in the consulting system. Hereby, power can be expressed with setting directives or demonstrating resistance [32] . Apart from that, the consultant is generally assigned with a certain portion of personal power based on his engagement by the client for the consulting project. The power position of the consultant in dealing with the clients can base on referent and expert power. Referent power relies on personal characteristics of the consultant and is closely related to his professionalism and his role as archetype. Referent power by the consultant is frequently observed when there is already a very close relationship between consultant and certain parties of the client organization. Expert power is conferred when the client believes the consultant is knowledgeable and the client regards this knowledge to be valuable [93] .

6.4. Legitimation and Sanctioning Consequences: Uncertainty in Consulting and the Urge of Control

Legitimation in the framework of the Structuration Theory can be practically interpreted as the level of norms, standards of morality, proper conduct and traditions that constitute organizational and social structures [94] . Bringing this dimension into the analysis of the consulting context, the fundamental portion of legitimation for consulting engagements is ascribed to the ultimate role of consultants as neutral instance within the organizational game. Due to the fact that consulting is a non-regulated business and is characterized as unbounded profession, consulting associations recommend their members to practice based on ethical guidelines and codes of conduct. These guidelines however have no legal binding for the consulting firms and cannot be enforced. Consequently, client firms have no guarantee that consulting firms comply with them. Monitoring a consulting firm’s compliance with these principles is hardly possible. Codes of conduct at best encourage appropriate behavior, but there is no institutional guarantee against the possibility of misuse [24] . As a consequence, client firms face a significant degree of uncertainty as there are no institutional orientations to distinguish qualified from non-qualified consulting providers [6] [62] [95] . Moreover, in practice it is shown that large consultancies prefer to use their own, widely recognized brand for differentiation purposes. Consultancies are concerned that any kind of standard qualification in the consulting industry (e.g. industry-wide academic certification programs) would make individual consultants more mobile, why they would require higher effort to retain qualified personnel. This uncertainty problem is not controlled by a superior instance: as the consulting industry is not a traditional regulated profession, it has no widely accepted or obligatory ethical standards the consultants have to comply with [96] .

Since questions on the legitimation of the consulting function lead to uncertainty towards the reliability of the consultant, the client may have a control demand about the consultant during the engagement. This has a sanctioning effect on the role of the consultant. The client as the holder of the relevant economic resources affected by the consulting project feels forced to gain transparency about consulting processes and sets short reporting intervals, since, at the end of the consulting engagement, the client organization faces its economic consequences [32] . The client is furthermore suggested to establish institutions to reduce uncertainty in that regard [97] . Those deficits are sometimes tried to be solved via detailed screening or with establishing a formal consulting governance by the client [98] .

Therefore, uncertainty is seen as a critical barrier for creating consulting readiness on the client side, which is of vital importance for the success of the consulting engagement. Consulting readiness comprises readiness for cooperation and receiving criticism during the joint development of strategies and solutions in the analysis phase as well as respective readiness for adopting transformation results in the implementation phase [85] . Consequently, building an effective relationship with the client organization is the predominant driver for the success of the consulting project [39] .

A further reason for the high level of uncertainty when engaging consultants originates also from the power position that the consultant usually gains within the client organization [79] . In particular, the consultant is assigned with legitimate power when he receives the mandate to reorganize departments or divisions with an amount of independence [50] . The power of the consultant is expressed by the possibilities for steering changes, as he can decide the way in which the analysis and the design of methodologies are applied, the manner in which the project is routed by setting priorities and the level of impact on decisions when preparing and communicating the analysis outcome [99] . This has increased relevancy when the consultant has been deeply integrated into the client organization and obtains a high level of acceptance. The consultant is then often awarded with an authority function within the client organization [39] . Moreover, the very nature of consulting often allows consultants to access confidential information of the client organizations. Hereby, they can sketch out and assess the client’s competitive advantages, specific knowledge, sociopolitical constellations and financial data. All this implies sensitive information for the client organization. This information access makes the client vulnerable to opportunistic behavior of the consultant [24] . Therefore, the existing mistrust can substantially obstruct an efficient working relation [100] .

As a consequence, the consultant’s possibilities for opportunistic behavior create mistrust in the client’s employees. There is substantial risk during the consultant engagement that the consultant’s actions and decisions are detrimental to the client organization. The client is faced with the hazard of hidden intentions by the consultant, which could be revealed after the contracting phase when the consulting project is in progress [98] . This is in line with other typical agency problems, such as hidden actions [opportunistic behavior of the consultant] or hidden characteristics [inadequate expertise and capabilities of the consultant] [97] . Even more, studies have shown that clients regularly assume that consultants also pursue their own strategic goals during the engagement [101] .

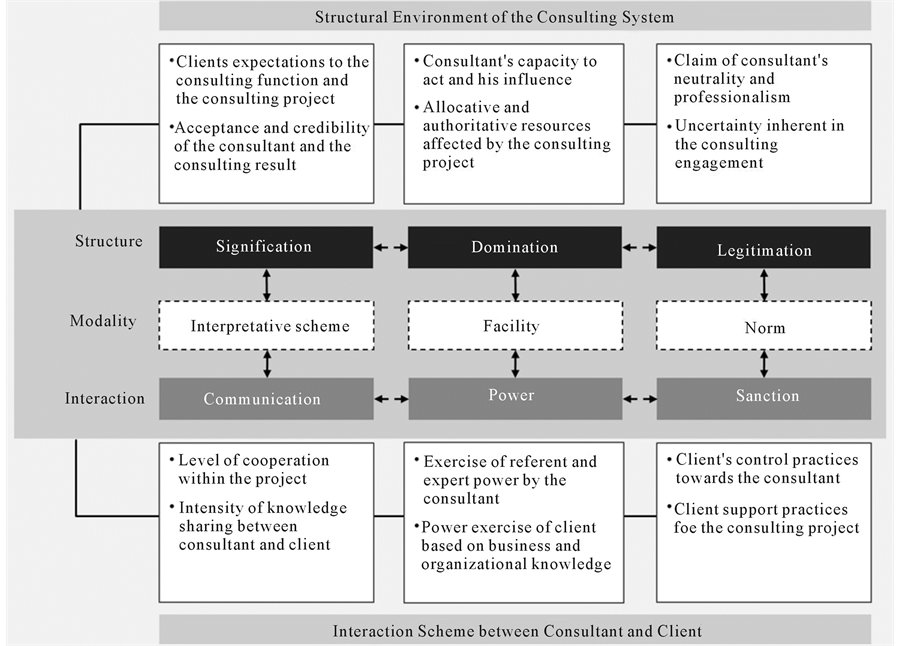

6.5. Summary: Consulting in the Dimensions of Structural Duality

Figure 2 outlines the capture of essential influencing factors for the quality of the consultant-client relationship based on the framework of the Structuration Theory. The structural elements of the consulting process as a social scheme cannot be perceived as isolated entities. They need to be analyzed in interrelated manner together with the types of interactions, as the execution of communication, power and sanction steadily reproduce these structures in the course of the consulting process. Furthermore, all structural properties of the consulting system

Figure 2. Consulting in the dimensions of structural duality.

are the medium and outcome of the contingently accomplished activities of actors involved in the consulting process. The structures like the client’s expectations and acceptance, the consultant’s capacity to act or inherent uncertainty are important features of any consulting situation. These can have both enabling and restricting effect on the interactions between the consultant and the client. Therefore, the interrelation of interactions between the consultant and the client [communication, power and sanction] and the structures determines how the quality of the consultant-client relationship can develop.

7. Conclusions and Reflections

With looking on the real long-term holdovers of consulting projects that rest in the client organizations, it is estimated that 80% of the consulting interventions from consultants do fail [102] . The high number of failed consulting projects, the evolved dissatisfaction of clients with consultants and the deficit of legitimization require the investigation of the effectiveness of the consulting service [103] . For that purpose, the reasons for failures in consulting engagements need to be determined. Scientists and practitioners particularly suggest the analysis of the consultant-client relationship for identifying advancements of effectiveness in consulting [104] [105] . With investigating the consultant-client relationship, it is risky to regard it as a sole input-output relation in the picture of a trivial machine, as a clear determination and prediction of the output in terms of the reaction and the response is not possible. It is also important to note that failures of consulting engagements cannot be fully attributed to the consultant. Instead, the consulting situation needs to be investigated on a holistic level.

Here, the Structuration Theory provides the potential to capture the consulting situation in a context of integrating the surrounding sphere. It infers the logic of interactions between the consultant and the client from the attendant organization and institutions with referring to the structural forces given in the consulting system that determine the actions of the consultant and the client. In the perspective of the Structuration Theory, the patterns of the relationship between the actors of consulting build the structural framework of the consulting system. The consultant-client relationship is constituted as a social system that develops in time and space through the interactions between consultant and client during the consulting engagement. The Structuration Theory regards the consultant and the client as role-taking and norm-fulfilling agents that act and communicate according to their images of what reality is. In doing so, they produce and reproduce structures of signification, domination and legitimation in a process of structuration.

The application of the Structuration Theory underlines the actual challenge of most consulting situations: the actual objective of many consulting projects is not to solely solve a distinct and isolated problem, but to initiate change and transition with all affected actors of the client organization in conjunction with that problem. This implies that structures have to be targeted that are reproduced by social practices of the client organization. The initiation of those social practices does however not follow any regularity or rationality and, therefore, does not enable generalizable predictability. Instead, social practices mainly base on individual interests. They also need to be analyzed in conjunction with power about resources (compare to approach of Hellmann in [52] ).

Furthermore, the Structuration Theory balances the conception of the consultant and the client as the agents of consulting with the inherent structures. On the one hand, both the consultant and client are perceived as individual and social agents that have reflexive capabilities. This is important to capture the subjectivistic components of their behavior. On the other hand, the Structuration Theory also emphasizes the importance of determinism from the existing structures of the consulting system, which enables or restricts the behavior of the consultant and client. This comprehension enables incorporating different categories and dimensions that influence the consulting process with highlighting its social impact on both the behavior of the consultant and the client. A lot of existing research on the consultant-client relationship tends to concentrate either on the perspective of the consultant (e.g. [52] [57] [106] -[108] ) or the client (e.g. [11] [48] [49] ). In contrast to that, it is important to create a view on both with focusing on the interactions between them, as this can be regarded as the outcome of the prevalent structural set that is inherent in the consulting system. With applying the Structuration Theory in this research work it is argued that the client organization is not uniform. Contrary to that, the client organization represents a heterogeneous cluster of actors, interests and inclinations involved in multiple and varied ways in the consulting project [109] .

Consequently, it is crucial to investigate how consultants and clients act and interact, and more specifically, why they act and interact in that way [30] . The actual output of the consulting system in terms of performance in achieving the goals of the project is determined by the structural set and by the way the agents of the consulting system adopting it as well as dealing with it.

The approach of the Structuration Theory provides an ontological framework for the study of the social actions of the consultant and the client and considers these actions as recurrent social practices with transformational capabilities. Moreover, it outlines the recursive interplay of social interactions within and across the involved client and consulting organizations. Structures of the consulting system, both in the broader sense and in the narrower sense, are viewed as “internal” to the action of the agents of the consulting project. Interactions between the consultant and the client are not conceptualized as isolated happenings or dyadic interrelations, but are considered as streams of interactions that are bound to their context. Furthermore, the consulting participants are seen as embedded in the social context of the consulting system, including the history of their previous interactions.

References

- Weiss, A. (2011) The Consulting Bible: Everything You Need to Know to Create and Expand a Seven-Figure Consulting Practice. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Nissen, V. (2007) Consulting Research—Eine Einführung. In: Nissen, V., Ed., Consulting Research: Unternehmensberatung aus wissenschaftlicher Perspektive, DUV, Wiesbaden, 3-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8350-9236-5_1

- Bund Deutscher Unternehmensberater e.V. (2013) Facts & Figures zum Beratermarkt, 2012/2013. Bonn.

- Sommerlatte, S. (2000) Lernorientierte Unternehmensberatung. Modellbildung und kritische Untersuchung der Beratungspraxis aus Berater-Und Klientenperspektive. DUV, Wiesbaden.

- Moldaschl, M. (2005) Reflexive Beratung—Ein Geschäftsmodell? In: Mohe, M., Ed., Innovative Beratungskonzepte: Ansätze, Fallbeispiele, Reflexionen, Rosenberger, Leonberg, 43-68.

- Armbrüster, T. (2006) The Economics and Sociology of Management Consulting. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511488467

- Faust, M. (2006) Soziologie und Beratung—Analysen und Angebote. Soziologische Revue, 29, 277-290.

- Mohe, M. (2004) Zur Programmatik einer kulturwissenschaftlichen Beratungsforschung. In: FUGO (Forschergruppe Unternehmen und gesellschaftliche Organisation), Ed., Perspektiven einer kulturwissenschaftlichen Theorie der Unternehmung, Metropolis, Marburg, 573-600.

- Reineke, W. and Hennecke, J.H. (1982) Die Unternehmensberatung: Profil-Nutzen-Prozeß. Sauer, Heidelberg.

- Timel, R. (1998) Systemische Organisationsberatung: Eine Mode oder eine zeitgemäße Antwort auf die Zunahme von Komplexität und Unsicherheit? In: Howaldt, J. and Kopp, R., Eds., Sozialwissenschaftliche Organisationsberatung— Auf der Suche nach einem spezifischen Selbstverständnis, LIT, Münster, 201-203.

- Mohe, M. (2003) Klientenprofessionalisierung. Strategien und Perspektiven eines professionellen Umgangs mit Unternehmensberatung. Metropolis, Marburg.