Current Urban Studies

Vol.04 No.02(2016), Article ID:67772,30 pages

10.4236/cus.2016.42014

Insurgent Urbanism, Citizenship and Surveillance in Kampala City: Implications for Urban Policy in Uganda

Paul Isolo Mukwaya

Department of Geography, Geo-Informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 20 March 2016; accepted 25 June 2016; published 29 June 2016

ABSTRACT

A great deal of work has been done on the nature of rights and the definitions of citizenship. However, little work has been done that explores how people perceive their citizenship rights and how they act on these perceptions especially in growing cities. High and low intensity protests have inscribed their presence and voice in Kampala city’s streets, thereby becoming integral components of the city landscape. The paper uses critical urban theory, insurgent urbanism and citizenship as its conceptual framework to: 1) examine the terrain of struggle and militancy and, how Kampala residents engage with the state beyond formal processes; and, 2) assess government surveillance actions aimed at (de) constructing of citizenship in the city. The paper illuminates these questions and elaborates the notion of insurgent urbanism using Mabira forest demonstrations, September 2009 Buganda riots, and Walk-to-Work’ (W2W) protests in Kampala City. The paper argues that the currents of militancy are very active across the city and the institutionalization and planning for insurgent claims and associated government responses in the broader urban policy terrain across the country.

Keywords:

Citizenship, Insurgency, Surveillance, Space, Policy, Kampala

1. Introduction

The city has become a defining life space for most of the world’s population with over 50% classified as urban and a further 61% becoming urban by 2025. In the early 21st century, three types of urban realities were emerging. The first was labeled a “flirtual (real-and-imagined) mobile city”; simultaneously t/here and re/present (Soja 1996) . The second urban reality is labeled a “blored (bloody-boring-luring) walled city”; the famous city of quartz (Davis 1992) and the walled and framed edge city (Dear and Flusty 1998) . The third urban reality is the “DISPER (ATE) city”; a glocal date/hate network metropolis (Sassen 2001) . In each of these cities, urban conflicts are not a new phenomenon (Isin, 2000) . These days it is not hard to enumerate all manner of urban discontents and anxieties, as well as excitements, in the midst of even more rapid urban transformations (Harvey, 2012) .

Modern cities had already become the sites of revolutionary politics, where the deeper currents of social and political change rise to the surface (Harvey, 2012) and these have brought back the status of citizenship and rights to the city in the spotlight (Ansley, 2010) . The likelihood of urban insurgency (i.e. guerrilla or terrorist) warfare in cities is increasing as the dual demographic trends of rapid population growth and urbanization continue to challenge the face of the developing world (Taw and Hoffman, 2005). Cities have become the frontline for struggles; the milieu for a whole range of new types of conflicts, such as asymmetric war and urban violence (Sassen, 2010) . They are sites where alternative practices, resistance and battles for control of urban space are waged (Blomley, 1997). The uprisings in the Arab world, the neighborhood protests in China’s major cities, Latin America’s piqueteros and poor people demonstrating with pots and pans-are all vehicles where people make social and political claims (Sassen, 2011; Harvey, 2012) to reassert their collective right to the city (Harvey, 2012) . The anti-gentrification struggles and demonstrations against police brutality in US cities, the 200,000 people marching in Tel Aviv―not to bring down the government, but to ask for access to housing and jobs; the indignados in Spain demonstrating peacefully for jobs and social services and the 1300-kilometer march to Brussels; are movements that seek to engage the powerful, not just protest against them (Sassen, 2011; Harvey, 2012) .

As this will be developed later, this paper considers an array of civil, political, social, and economic rights, including the rights to shelter, clean water, sewage discharge, education, and basic health―in what Lefebvre (1991) referred to as “the right to the city.” The right to the city is, therefore, far more than a right of individuals or group access to the resources that the city embodies: it is a right to change and reinvent the city. It is, moreover, a collective rather than an individual right, since reinventing the city inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power over the processes of urbanization (Harvey, 2012) . The struggles are performed not only in the high courts of justice and ministerial corridors of government institutions but also in the streets of cities, the squatter camps, and the everyday life spaces of those excluded from state’s citizenship. The protagonists of this contest use non-formalized channels, create new spaces of citizenship, and improvise and invent innovative practices, all of which attract a captive constituency (Miraftab & Wills, 2005) .

Urban groups are emerging as contenders for power in East Africa as their capacity is extended by the acquisition of information: information about alternative conceptions of politics and justice; information which can challenge a government’s version of events and indeed its very legitimacy; and information about other individuals’ aspirations and critiques. As these groups mobilize, scenes of conflict between riot police and demonstrators are a familiar feature (Baker, 2015) . This paper explores the urban insurgency debate by: 1) examining the terrain of struggle and how Kampala residents engage with the state; 2) reviewing surveillance actions aimed at (de) constructing citizenship and rights to the city. The rest of the paper unfolds as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical framework against which the whole paper is anchored. Section 3 delves into the city setting in which the paper is situated and outlines the general trends within which urban policy operates. Although the whole intensions of the paper feed into the broader urban environment in Uganda, the focus of the paper is on Kampala City, the largest commercial and administrative capital of Uganda. The city is not only a testing ground for Uganda urban policy ideals but also for urban management on a broader scale. Section 4 discusses the data collection methods that were employed. Section 5 presents the results and finally Section 6 draws together the main findings into their wider urban policy implications for Uganda.

2. Critical Urban Theory, Insurgent Urbanism and Citizenship

The paper is anchored in critical urban theory and applies insurgent urbanism, a concept first introduced by Holston (1998) to explore the terrain of struggle and how Kampala residents engage with the state. The notions of critical urban theory have determinate social―theoretical content that is derived from various strands of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment social philosophy, not least within the work of Hegel, Marx and the Western Marxian tradition (Calhoun, 1995) . Brenner (2009) as concerned with: 1) analysis of the systemic, yet historically specific, intersections between capitalism and urbanization processes; 2) the changing balance of social forces, power relations, socio-spatial inequalities and political-institutional arrangements that shape, and are in turn shaped by, the evolution of capitalist urbanization; 3) exposing the marginalization, exclusions and injustices (whether of class, ethnicity, “race”, gender, sexuality, nationality or otherwise) that are inscribed and naturalized within existing urban configurations; 4) deciphering the contradictions, crisis tendencies and lines of potential or actual conflict within contemporary cities, and on this basis, 5) demarcating and politicizing the strategically essential possibilities for more progressive, socially just, emancipatory and sustainable formations of urban life. Critical urban theory emphasizes the politically and ideologically mediated, socially contested and therefore malleable character of urban space-that is, its continual (re) construction as a site, medium and outcome of historically specific relations of social power. Critical urban theory is thus grounded on an antagonistic relationship not only to inherited urban knowledge, but more generally, to existing urban formations. It insists that another, more democratic, socially just and sustainable form of urbanization is possible, even if such possibilities are currently being suppressed through dominant institutional arrangements, practices and ideologies (Brenner, 2009) .

Citizenship means different things to different people but it has become a crucial weapon, not only in the struggle against social and economic exclusion and inequality but―most importantly―in the widening of dominant conceptions of politics itself and social organization (Alvarez, Dagnino, & Escobar 1998) . These struggles constitute what is referred to as citizenship; the foundational debates about political association or the purposes for which people agree to deal with collective affairs. The status of citizen denotes a basic role for people as self-directed actors in a political context, and is often distinguished from “subject,” which implies a more passive and subordinate status (Clancy, 2014) . Thus, the redefinition of citizenship undertaken by social movements, to confront the existing boundaries of what is to be defined as the political arena: its participants, institutions, processes, agenda and scope (Alvarez et al., 1998) . Re-conceptualizing the notion of citizenship, and shifting its center from the state to the people, and stressing a pluralist model (Young, 1990) has led to a plethora of new definitions of citizenship, including participatory citizenship, inclusive citizenship (Kabeer, 2002) , active citizenship (Lister, 1997) , and citizenship from below or insurgent citizenship (Holston, 1998) . These definitions signify an alternative conceptualization of citizenship, in which new meanings, agencies, and practices of citizenship are articulated. In this alternative model, practices of citizenship extend beyond taking up invitations to participate in what Cornwall (2002) calls invited spaces of citizenship that extend to forms of action that citizens innovate to create their own opportunities and terms of engagement. Miraftab (2005) , referring to these alternative spaces of participation as invented spaces of citizenship, has underlined the significance of expanding the arenas of practicing citizenship to include both invited and invented spaces of citizenship.

The use of the term insurgent practice is a derivative of Holston’s (1995) insurgent citizenship, representing a reaction to the modernist spaces that physically dominate cities today. Insurgent citizenship in this vein directly challenges the heart of the belief of the modernist, utopian political project that the state is the only legitimate source of citizenship rights and practices by claiming new and other sources rooted in the present, and asserting their legitimacy (Lamarca, 2010) . The city is not a neutral container but a political space in which meaning of citizenship is daily contested and as Holston argues, everyone should take seriously the insurgent practice because they reflect the reality of contemporary urban life (Knudsen, 2007) . For Kampala City’s case, insurgent practice is sued here as laying claims to urban spaces, to assert new forms of identity and ways of being in the city; which ultimately resonates with the lived spaces and realities of urban living. Insurgent urbanism is an interesting way of looking at how everyday spatial practices and manipulations can lead to new discourses of citizenship (Knudsen, 2007) . Holston (1998) states that such insurgent forms are found in both grassroots mobilization and in everyday practices that in a variety of ways empower, parody, derail or subvert state agendas, and thus are fundamentally found in struggles over what it means to be a member of the modern state, or a citizen.

Insurgent practice is specifically defined here as the process of making claims towards inclusive and substantive citizenship rights and towards achieving the right to the city (Lamarca, 2010) . Furthermore it finds resonance with one of Castells’s (1983) notions of urban social change as a process where new urban meaning is produced as social movements or mobilizations impose a new urban meaning contrary to the institutionalized one and against the interests of the dominant powers. Insurgent practice is connected to claims emerging from marginalized and oppressed groups, fundamentally seeking to transform power dynamics and relations in the city (Lamarca, 2010) . Foucault (1998) insists that where there is power, there is resistance. Since planning relies on power to mould and dominate urban spaces, it can be argued that where there is planning there is resistance.

The phrase “Right to the City” is attributed to Lefebvre in the late sixties, when social movements were springing up all over the place, very visibly in Paris, claiming rights to use the city, live in the city, work in the city, and agitate in the city, in peace. It was a radical, indeed revolutionary, phrase: people had the right to determine their own environment and living conditions, and neither government nor any other powers had the right to tell them what they could or could not do (Marcuse, 2005) . Scholars that believe in this approach consider that the production of urban space is achieved by daily struggles and mobilization from below. The other interpretation of the right to the city led by scholars such as Parnel and Pieterse (2010) define it as a collection of rights in the city. However, according to Zerah, Lama-Rewal, Dupont and Chaudhuri (2011) , the right to the city is equivocal on at least three points. First, it refers, at the same time, to entitlements and to claims, that is, to the domain of the legal and to that of the moral. It is concerned with existing rights (such as the right to vote in elections) but also with claimed rights (such as the right to public transport). The second is the right to live in the city, to work in the city, to move in the city etc. This remains formal as long as the city is not made affordable (focus on housing), practicable and accessible (focus on transport) safe (focus on street lights, police, etc.) and livable (focus on urban services). The third one is the right to public policies and political participation (in a broad sense) to enable better access to, and use of, the city (Zerah et al. 2011) .

Nemeth (2010) finds that three interrelated entitlements comprise the “right to the city”: the right to access physical urban space; the right to be social, to express oneself and interact with others; and the right to representation, belonging and citizenship. The first right simply denotes the right to be in public space, to occupy and inhabit it (Marcuse, 2005) . The second right is the ability to live a cosmopolitan lifestyle, one that provides the option to engage in unmediated interaction or to retreat into introspective anonymity (Lofland, 2000) . This right implies the change to lead an urbane, full, diverse life (Marcuse, 2005) that finds renewed centrality in places of encounter and exchange (Lefebvre, cited in Mitchell, 2003 ). The third right involves the ability to actively produce space and determine one’s own vision of the good life (Young, 1990) . This right entails opportunities for representation, participation and appropriation, and involves meaningful access to decision making channels (Lefebvre, 1968).

3. Selected Studies on Urban Insurgency in Kampala City

Post-2006 Uganda has created “bastions of protest movements” and the sites of urban insurgency in Kampala City have proliferated. Unprecedented levels of popular protests from several social groupings (Golooba-Mutebi & Hickey, 2013) have characterized this period including the micro-politics of work (markets, taxi parks, shops, etc), schools/universities, civil society organizations, communities and neighborhoods, political parties, women activists, youth groups, lawyers, monarchists, civil servants, and human rights activists. These groups have united not only in their opposition to government policies, but also, in contesting the established parties’ monopoly to articulate socio-economic and political interests and demand political reform.

Academic scholarship on urban protest movements in Uganda is however limited except for media coverage and political statements. Available scholarly evidence on protests in urban areas in Uganda is dated (e.g. Thompson, 1992 ), and protests were seen in the context of electioneering and political contestations (e.g. Conroy-Krutz & Logan, 2012; Helle, Makara, & Skage, 2011; Helle & Rakner, 2014; Mulumba, 2011; Tabachnik, 2011; Titeca & Onyango 2012 ); and, structural transformation challenges across the country (e.g. Golooba- Mutebi & Hickey, 2013; Kjaer & Katusiimeh, 2012 ). Izama & Wilkerson (2011) and Mbazira (2013) describe the events surrounding the W2W protests across the country and the government responses to them. He observed that protests arose from the loss of confidence in the government because of its failure to meet the needs of the people, in spite of promises to do so.

Baker (2015) offers an explanation of the continuation of forceful tactics against political protest in a context of changing methods of information gathering, organization and mobilization by urban activists resulting from their access to internet and communication technology. The paper observes that the regime is caught between legally allowing protest and yet, conscious of their fragility, determined to crush opposition and the military leadership in Uganda relies heavily on continued police violence. The paper concludes that: 1) failure of the police to adapt their public order policing to the new protest environment leaves them increasingly ineffective and unpopular; 2) it is likely to provoke an escalation of violence and may both undermine the legitimacy of the regime and reverse their attempts to open political space that justified their rebellions against former autocracies; and, 3) the regime in Uganda is facing rising contestation and diminishing support as urban groups, equipped with new resources, particularly easily received and transmitted information, seek access to the polity.

Goodfellow (2011) on the other hand alludes to the fact that forms of popular participation in urban affairs in Uganda are institutionalized through informal political processes. He argues that the regular mobilization of urban social and economic groups into protests and violent riots has institutionalized a politics of “noise”. As a response, legal maneuvers linked to the rise in urban based protests and riots have often become violent and resulted in aggressive crackdowns, violence and institutional repression in order to maintain systemic power (Goodfellow, 2014; Vasher, 2011; Warigia & Camp, 2013) . On political violence in Uganda, Kakuba (2015) recommends that a conducive and just socio-economic and political environment for promoting political trust and tolerance is important.

4. The Setting: Kampala City

The paper uses Kampala City to illustrate the terrain of struggle for city residents. The city is the major administrative and commercial centre of Uganda. Kampala City dominates the urban landscape accounting for one third of Uganda’s urban population. Greater Kampala boasts of population of 3.5 million and is growing fast, both on account of redevelopment within the city and expansion on the periphery (World Bank, 2015) . The city has recorded the highest rates of population growth and if current patterns of growth continue, Kampala will become a megacity with a population of more than 10 million in the next 20 years (World Bank, 2015) . This growth is not influenced by natural rate of increase, but rather rural urban migration where most people migrate to the city for employment opportunities, spouses, better standard of living and services, and security while others have migrated due to the loss of their “bread winners”, peer influence, and loss of land in rural areas (Avuni, 2011) . While accurate data on the distribution of economic activity in the city are not available, it is estimated that about 80% of the country’s industrial and services sectors are located in the city. The economic future of Uganda is thus intrinsically tied to the performance of the city as a locus of productive activity and investment. Protests have increasingly taken on an urban character across the country but I chose to explore activities in Kampala City because:

For the last five years the Kampala City has developed as the hotspot for protest movements in the country. The city evolved into a hive of political activity and popular mobilization; and this presented the nation’s capital as the perfect setting for examining the roots of all the political contestations that were visible across the country. A global annual survey showed a heightened sense of socio-economic insecurity in most parts of the world and the Civil Unrest Index given by Bender (2014) placed Uganda in the high risk category. Kalyegira (2011a, 2011b) reports that 2011 was one of the most difficult years ever for the average Ugandan. The only tougher years were 1979 and 1980, following the Tanzania-Uganda war, and 1976-1977, when a western led economic boycott and a financial sabotage by anti-Amin guerrillas crippled the economy (Kalyegira, 2011a; 2011b) . Two other traditions of political action in recent history included the popular struggles involving the “Bana ba Kintu” strikes and boycotts of 1945 and 1949, the “Twagala Lule” demonstrations of 1980, in Buganda, as well as taking of power by armed guerrillas (Mamdani, 2012) .

Several groups find Kampala City an appropriate place to brings government institutions to account in what Goodfellow (2011) describes as the formal and informal but highly public and disruptive processes that characterize the city’s political life. As it became evident legal demonstrations have been less effective while rioting was more effective to win further attention and concessions from government (Goodfellow, 2011) . The longest protests and riots took place at a time when the government renewed its policy attention to urban areas across the country including Kampala City. The central government had just taken over the administration of Kampala City to create the Kampala City Capital Authority that was aimed at bringing an “urban renaissance” to the city and give it a fresh start after government reconstituting the city into the Kampala Capital City Authority. In a sense, rioting has been institutionalized; as it forms part of the “rules of the game” of state-society interaction in Kampala City. In any case, the fact remains that Kampala’s streets are becoming the battleground where an economically marginalized and politically frustrated opposition flexes its muscles against a government keen on deploying instruments of state violence to quell popular protests (Kock, 2011) . I believed that Kampala City’s serves as a useful platform to explore insurgent urbanisms and other urban authorities across the country could draw from Kampala’s past experiences, as well as those of other cities around the globe to chart a new future for their citizens.

Concentration is given to particular actions in Kampala City to illuminate the processes and reasons whyh such campaigns are created. Lehman-Wilzig and Ungar (1985) indicate that the use of newspaper reports constitutes the generally accepted mode of gathering data on protest and socially disruptive events. Access to newspaper reports over the 2006-2016 period was crucial for identifying the major protests movements as well as the strategies and decisions of the individuals and groups involved. I worked back and forth document archives to flesh out the stories behind official correspondence and reports, and files to check and corroborate information. I analyzed this case largely by document analysis and this constituted the following elements:

1) Reviews of Kampala City urban policy framework and procedures and how they influence urban protests by studying important moments in the Kampala City Capital Authority decision making process, i.e., council meetings and other forums in which the different stakeholders interacted.

2) Collation, scrutiny and analysis of other policy documents, bills/acts and press statements, manuals, newspaper articles and blog posts. Some of the events and protest movements were reported online and captured live by electronic media especially television stations. It was therefore necessary to follow these events and reports on the newspaper, event organizers websites and blog postings. For example, information at Activists for Change (A4C) at http://activists4change.blogspot.com, www.williamkituuka.blogspot.com, http://theafricanist.blogspot.ug/2011/05/walk-to-work-campaign.html, www.observer.ug, www.monitor.co.ug, www.ugandaspeaks.wordpress.com, www.fdcuganda.org, www.ugandacorrespondent.com, www.independent.co.ug and www.kashambuzi.com provided background materials to illuminate the issues of interest in this paper.

5. Waves of Protest and Construction of Citizenship

It is possible to identify distinct phases of urban protest that have swept the country and more specifically Kampala City. For a long time, urban Uganda didn’t have a well-established culture of expression of public political discontent (see for example, Bratton & van de Walle, 1992 ) but events following the 2011 elections left behind a new political actor in Uganda: a self-confident and politically active urban protest and militant culture. Most Ugandans have now started to understand that their collective power if harnessed properly is capable of causing change. Although, reactions to the protest movements in Kampala City were generally predictable, with the NRM’s or “law and order” interpretations predominating, the protest movements have essentially been an outburst of anger and resentment of Ugandans against the government and this can be pointed to a number of events and crises, which according to Benyon & Solomos (1988) result in frustrated expectations, cumulative disappointment and increasing resentment.

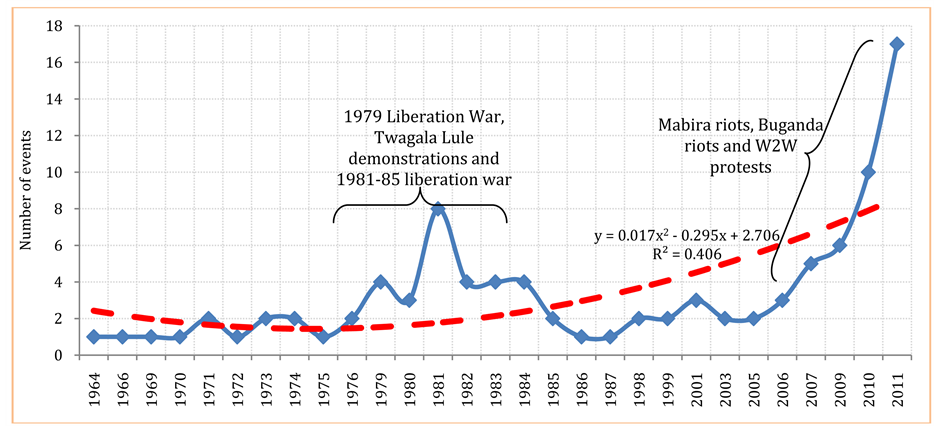

Figure 1 shows the number of urban social disorder movements in Kampala City since 1964. The figure

Figure 1. Number of urban social disorder movements in Kampala City (1960-2011). Source: 1964-2005 and 2006-2011 data were derived from http://www.prio.no/CSCW/Datasets/Economic-and-Socio-Demographic/Urban-Social-Disturbance-in-Africa-and-Asia/ [29th January 2016] and newspaper archives respectively.

shows that three periods stood strongly; i.e. 1979-1984, 2006-2009 and 2011. Between 2006 and 2011, the number of protest events in Kampala City rose by 1600%. Ostby (2010) reports ten1 urban social disorder events as having occurred in Kampala between 1986 and 2006. These have dramatically increased since 2006 and reviews of newspaper reports suggest that between 2006 and 2011, at least 27 protests were recorded in various areas in the city. These estimates may be higher in Uganda Police records and since the beginning of 2012; it appears that the protests are increasing.

While the government increasingly sought to de-legitimate protest, its policies exacerbated the citizens’ discontent and led to highly politicized anti-government orientations. The paper uses three examples to frame urban insurgency in Kampala City. Protests in Kampala City have been interpreted in contrasting ways but the examples given in the paper give illustrations that demonstrations and riots have become the “normal” mode of exchange through which urban-dwellers engage with the state. The paper argues that spaces of urban citizenship and expression of protest since 2005 can largely be discerned to fall under three distinct but related movements and these include:

1) The Mabira Forest protest (2006-2007);

2) The September (Buganda) 2009 riots;

3) Walk to Work (W2W) and related protests (2010-To date).

5.1. Mabira Forest Protest Movement (2006-2007)

Ugandans took to the streets in 2007 to demonstrate against President Museveni’s government’s move to give away parts of Mabira Forest to Sugar Corporation of Ugandan Limited (SCOUL). The secrecy surrounding the giveaway, the timing of the announcement (shortly after the 2006 elections), and the enormous economic value of the public asset involved led to rumors of collusion between Uganda’s most politically powerful man and one of its most wealthy. Led by two Members of Parliament, Beatrice Anywar and John Ken Lukyamuzi, local environmental civil society organizations, a loose coalition of national and international institutions and actors, including trade and ethnic associations, Buganda kingdom, church groups, prominent academics, political opposition, media figures, multilateral governance institutions, transnational environmental networks and donor countries a spirited fight dubbed “Save Mabira Activism”, was organized to fight the giveaway. Even when the forest is located over 60 kilometers away from Kampala City, several thousands of Ugandans poured to the streets of Kampala City and the confrontations with the security forces degenerated into violent street riots that claimed the lives of several people.

President Yoweri Museveni’s insistence on giving away part of the forest to SCOUL (Nampewo, 2013; Honig, 2014) was a decision that continues to surprise and irk his enemies and allies alike. There was a lot of talk that Museveni’s strong stand in wanting to give away Mabira forest was not connected to sugar production per se. An extended litany of reasons for the giveaway is given by Museveni (2007) and also captured by Akaki (2011) . However, a senior Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) official added a fresh twist, also captured by Kjaer & Katusiimeh (2012) to the brewing battle for Mabira by suggesting that President Museveni’s ruling NRM party received unspecified amounts of money from the sugar company to fund its 2006 election campaigns for which it now felt indebted. Otim (2011) ably captured the FDC message;

They were trying to fulfill their part of the deal by sacrificing a very important resource. In fact, one gentleman claiming to be a security operative told UGPulse that it was suspected Museveni promised to give Mehta part of Mabira forest for the support Mehta provided to Museveni and NRM since the start of the guerilla way back in 1981. The businessman had been patient, waiting for the Promised Land to be given to him and it had reached that time when the president felt he should deliver on that promise.

What the government may not have anticipated was how fast public opposition to the SCOUL giveaway would congeal into an effective counterforce (Child, 2009) . Without clear leadership or strategic engagement, the spontaneity of discrete discourses coming from an array of significant segments of actors to save the forest, was striking. This compelled the Museveni government to backtrack on a forest giveaway that it had fought hard to push through (Child, 2009; Honig, 2014) . In what has been called an astonishing groundswell of public reaction and an iconic symbol of civil society action, the normally parochial politics of the environment emerged on an expanded political terrain.

The widespread use of internet and other electronic information technologies was an important tool during the early stages of the protest for disseminating information and organizing resistance, and ultimately led to what has been called “one of Africa’s first grassroots modern ecological protest campaigns” (Child, 2009) . The campaign to save the forest was indicative of African environmental struggles in terms of its heterogeneous civil society composition and ambiguous commitment to conservation, yet it also stood out as a powerful demonstration of how civil society movements that ostensibly championed the environment would also nurture more radical demands for democratic accountability (Child, 2009) . Environmental NGOs sent out news alerts to their supporters and published informational web pages, while individual activists published ample literature on their personal blog spaces, emails and SMS text messages. The largest cyber expression of public opposition appeared on the Save Mabira Forest Petition which was launched in September 2006 and within a month had recorded several thousands of signatures per day.

Less sophisticated forms of communication were also employed by activists, including the organization of public meetings, and the distribution of flyers and other “Save Mabira” paraphernalia, including T-shirts, calendars and bumper stickers. Outside of environmental NGOs, students were among the vanguard of the protest movement. Only a month after the giveaway became public knowledge, 300 students from Makerere University marched through the city with a brass band leading the way to the Parliament buildings where they stopped to deliver their own petition. Because of the early public support for the campaign, media coverage intensified over time. By April 2007, it was virtually impossible for an urban Ugandan to pass through a single day without hearing, seeing or reading a radio, TV or newspaper account of Mabira related events (Child, 2009) .

5.2. Buganda Riots (2008-2009)

The Kingdom of Buganda2 and its monarch, the Kabaka, vis-à-vis the rest of the country, is a fault line that shapes Uganda’s politics (Barkan, 2011) . The Ganda reside in south central Uganda along the shores of Lake Victoria, an area that includes the capital city of Kampala. In a country where 87 percent of the population resides in the rural areas, they distinguish themselves as the most urbanized and educated ethnic group (Barkan, 2011) . Although their dominance today is less pronounced, a continued political issue and the basis of political mobilization throughout the country’s history has been the debate about the relative autonomy granted to the Kingdom of Buganda and other traditional kingdoms within the larger Ugandan state (Barkan, 2011) .

Competing explanations of the underlying drivers of the Buganda riots are ably captured by MRT (2009) , Suransky, Kooster, & Seela (2009) and the International Crisis Group (2012) . Previous attempts by the Kabaka to visit other parts of Buganda kingdom Nakasongola in 2008 were stopped by government claiming that it could not protect him. Kingdom ministers then announced he would visit Kayunga in September 2009. Mengo (the seat of Buganda kingdom government) opposes Museveni on the balkanization of Buganda Kingdom through the creation of sub-ethnic districts. Mengo was infuriated by what it perceived as Museveni’s determination to undermine Buganda’s political influence, to demolish the glory of Buganda kingdom and to deny it Federo while openly supporting non-Baganda groups and individual interests against Buganda (Guweddeko, 2013) . Frictions simmered between the Kabaka of Buganda Ronald Mutebi, the central government and the leader of the Banyala exploded into bloody violence when on an advance trip, Buganda’s Katikiro (Prime Minister) Walusimbi and other ministers were blocked by armed police and the army from traveling to Kayunga (Suransky et al., 2009; Izama & Wilkerson, 2011; Vasher, 2011) in preparation of the Kabaka’s visit for the National Youth Day celebrations two days later.

Leaders of the Banyala ethnic group in Kayunga3 had opposed the visit (HRW, 2009; Vasher, 2011 ) and government authorities for fearing violence denied the King Ronald Muwenda Mutebi II to visit his subjects in the district (Kibanja, Kajumba, & Johnson, 2012) and reassert authority over his territory. The Ssabanyala insisted the Kabaka should inform him officially first: short of which was bloodshed, but Museveni insisted on two conditions for the visit: that both cultural groups meet with government to negotiate the trip, and Buganda Kingdom radio station; Central Broadcasting Service (CBS) stop criticizing the NRM. Since these terms were tantamount to capitulation, Buganda officials refused to budge (Vasher, 2011; International Crisis Group, 2012) . When the Kabaka declined to meet Captain Kimeze, the government stepped in apparently to protect the interests of the Banyala minority group (Asiimwe, 2009) .

When it appeared that the Kabaka was determined to visit Kayunga no matter the odds, the army further surrounded his palace in Kireka (a suburb of Kampala City) on the night of September 12, 2009 (Independent, 2010) . The government’s actions and perceived insult to the Kabaka united the Buganda youth against the central government (Conroy-Krutz & Logan, 2012; Vasher, 2011) . The Kabaka’s supporters took to the streets in protest ( Conroy-Krutz & Logan, 2012 ; HRW, 2014), provoking a backlash from security forces. The riots; christened the Buganda riots and other acts of resistance were epic in length and intensity as hundreds of the king’s supporters rampaged through the streets of Kampala, setting up barricades, looting shops and fighting running battles with police. The MRT (2009) captured moments of the riots as;

In the early stages of the demonstrations on September 10, some protesters resorted to violence in some areas of Kampala, burning at least five cars, one passenger bus, and one delivery truck, blocking some main roads with burning tires and debris, looting shops, and throwing rocks at police and members of the armed forces. In Nateete, protesters burned a police station. In Bwaise, a factory was set on fire. No one was reported injured in either fire, and local hospitals did not report any burn victims.

A number of disturbing urban policy realities emerged during the Buganda riots. First, the geographical spread, breadth and diffusion of the riots was like a wildfire and this came as a complete surprise to government, the security forces and the general public. Unrest in previous years had centered on Kampala’s Central Business District and had not extended into the populous residential neighborhoods (MRT, 2009) of Bwaise, Natete, Ntinda, Kisenyi, Kasubi, etc. However, three days of total city paralysis and effective closure of economic activity in the city were followed by the spread of riots to other towns across the country including Mukono, Mpigi, Kayunga and Masaka (Kibanja et al., 2012) . Museveni’s presidency, for all its successes, has performed poorly in promoting the pre-eminence of state institutions in the face of rival institutional frameworks anchored in regionally and ethnically based communities (Lindemann, 2010). The riots were a sign that the state’s exclusionary practices towards Baganda elites may be alienating the wider population (Goodfellow, 2010) .

The riots revealed that Baganda youths had become radicalized and militant over the years, and could easily be mobilized to challenge the state. The profile of the stone throwing, tyre burning youth on the streets of Kampala and the suburbs was easy to sketch. A larger majority of the rioters was under 25 years of age, not very educated and most likely not gainfully employed and the riots provided them a chance to be heard and perhaps to be taken “seriously”, for the first time in their lives (Suransky et al., 2009; Kalinge-Nyago, 2011a; 2011b) . The growing group of unemployed young men is an urban underclass that is prone to manipulation for political ends (Suransky et al., 2009) . The impoverished young Baganda strongly believed that their misery under Museveni and National Resistance Movement (NRM) government would only be cured through Mengo, Kabaka Mutebi and the physical resources of the kingdom including areas like Kayunga supposedly being sliced off by the NRM (Guweddeko, 2013) .

Rioting youths and syndicates questioned and established rules of belonging and contested those territories that belonged to “no-one”; while city residents had to make continuous assessments of zones of safety and danger, and act accordingly. Rioters drew on available resources and ideologies to define urban spaces as “ours,” making territorial claims to places, seeking to exclude others, as well as trying to impose conformity. Thus, the city was re-structured spatially and the rhetoric of belonging and behavior became heated. Available evidence suggests that the hotspots in the city were divided into two zones: that for the Baganda loyalists and their associates; and the zone for the outsiders. Reports of hatred of the non-baganda (“abagwira”) increased and television footage during the riots indicated that Baganda youths meted attacks upon “abagwira” resident in the city; a concern that demonstrates the complex dynamics of urban struggles, identity and who has the legitimate right to Kampala City. The rioters attacked any presumed beneficiary of the NRM regime including the rich, regardless of whether they were fellow Baganda, assumed Banyankore or the foreigners enjoying the privileges of “investors” and “ghost investors” (Guweddeko, 2013) . Indeed in the confrontations with the abagwira, one was required to “okulanya”-a custom of reciting one’s ancestral line on both parents sides; a well-entrenched and traditional way for a Muganda to introduce himself or herself including personal names, father, grandfather, lineage details and ancestral home (obutaka); village (ekyaalo) and county (ssaza) as a way of discovering any previously (un) known relations (Suransky et al., 2009) .

Thirdly; the violence reflected an increasingly fraught struggle between the Buganda authorities and the Ugandan government. Thus, while the riots were partly a show of Buganda force, they were also borne out of fear of the secessionist desires of districts such as Kayunga, which would diminish the kingdom’s influence and reduce its overall power if Federo was restored (Economist, 2009) . It was also suspected that the central government has stirred up the controversy to undermine the unity of Buganda Kingdom, given that the move to support the Banyala against Buganda could be seen as another manifestation of the same divide-and-rule strategy that led to the restoration of Buganda and other kingdoms in the first place (Suransky et al., 2009) . By the time the authorities regained control and the king agreed to postpone travel to Kayunga, the rioting had exposed a deep undercurrent of anger and frustration (Greste, 2009) further exposing the tension between state control and the ambitions of the traditional Buganda kingdom. Several Buganda kingdom sympathizers reminded other Baganda that the Kabaka and his subjects in Buganda were in captivity. Venomous remarks that received free, airplay on the radio waves included Buganda should secede from Uganda’, “Abagwira baddeyo gyebaava” (non-Baganda should go back to where they came from).” Since we (Baganda) are under constant attack by the enemy, the messages emphasized: “it was time for every loyal Muganda to openly declare their full allegiance to the Kabaka and our other institutions. They declared that Buganda would remain strong… “Buganda tetisibwa tisibwa” (nobody scares Buganda), “Abaganda temwemalako ttaka nga muliguza abagwira’ (Baganda, don’t finish all the land by selling it to non-Baganda).”

While the president reported that the rioting was not about failing to address the problems concerning Baganda accusing elements trying to use that monarchy to get political power and meddling in partisan politics to undermine the government, Baganda loyalists argued that they didn’t want to take power from central government at all. All they wanted was the legal authority (territorial and social power) and self-government to run their own affairs in a federo system, just as it was in the post-colonial constitution (Greste, 2009) . Broadly, the crisis involved Museveni and Mengo claiming to have created the other. Guweddeko (2013) reported that deep seated animosities and broken promises exist between Buganda and the NRM government over the 1981 NRM/A War Agreement. The acrimony between Buganda and the central Government stems from the failure of the NRM government to honor Buganda’s demands. These demands were part of an agreement that was reached between Buganda and the NRM as a prerequisite for Buganda’s involvement in the 1981 National Resistance Army (NRA) bush war (Mugagga, 2012) . Museveni claims he won the war “alone”, made no “agreement to restore monarchies” but rather philanthropically reinstated Buganda Kingdom, Kabaka Mutebi and the Mengo administration while Mengo counterclaims that Baganda received, hosted, united under NRM/A and brought Museveni to power (Guweddeko, 2013; Conroy-Krutz & Logan, 2012) . Economist (2009) puts it succinctly;

He came to power with the help of Baganda peasants that had suffered during the Amin and Obote regimes, and he shored up this support by granting the wish of traditionalists for the return of a monarchy to the Buganda kingdom in 1993.

5.3. Walk to Work (W2W) and Territorial Expressions of Discontent

The W2W protest movement in Uganda was born as an umbrella committee of interest groups whose principal demand was, as its name suggested, walk to work and live with the high cost of living. A day to day description of the first days of the W2W is given by Goodfellow (2011) and Kizito (2015) but within the prevailing hardships, W2W was an expression of people’s frustrations with escalating fuel and food prices together with the reckless spending of public money by government, without any sign of regard or feelings for ordinary people when the majority of Ugandans were living in abject misery (Bagala, 2012a; Mugisha, 2011b; Twinoburyo, 2011a) . The W2W protests were led by Activists for Change (A4C); a non-partisan pressure group that hoped to use nonviolent, peaceful action to hold the Uganda government accountable for its policies. As well as bridging class and status divides, the urban based A4C skillfully used its sympathizers including the media to mobilize support and, through its diversity and leadership, drew in followers with diverse tribal, linguistic and regional identities. Clancy (2014) puts it that the A4C provides for;

Citizens as formative agents, in the sense of providing their consent for the establishment of political arrangements and thereby bestowing legitimacy. They could also, or alternately, be considered as participative agents, in the sense of holding basic interests and rights that can be asserted as part of group deliberations.

Launched on 11th April 2011 in Kampala City, after the February 18th, 2011 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections, the W2W protests were meant to highlight the deepening economic crisis in the country and how it impacted on ordinary working class Ugandans. Sejusa who is quoted by Lubwama (2016) questions the ideological depth of the W2W campaign and whether it could manage constructively the rather complex dynamics of moving a system from democratic centralism to liberal democracy without disrupting the social and political cohesion of the state. That notwithstanding, the campaign was designed to harness popular discontent when inflation had weakened to single digit figures following the global downturn, after averaging 12.5% during 2008-9, but had climbed steadily in the past six months-driven by rising food and fuel prices, and a weakening Ugandan shilling. In addition, government spending rose ahead of the polls-in line with January’s supplementary budget of Uganda Shillings 600 billion-exacerbating these pressures (Izama & Wilkerson, 2011; Mbazira, 2013) . When a government has been in power for 30 uninterrupted years, it becomes inevitable that people will start asking questions about service delivery, accountability and crime and so on and ultimately will start demanding for change of some sort (Lubwama, 2016) . The mission of A4C was to engage in non-violent action to foster peaceful change in the management of public affairs ( Aljazeera, 2011 and Human Rights Watch, 2012 ) and to compel leaders at all levels to exercise sensitivity and compassion in the allocation of scarce and hard-earned resources. The key pillar on which A4C wished to anchor the values of the country was that all people had the national obligation at all times as Ugandans to hold leaders accountable.

By May 2011, not only had the W2W campaign continued, it had actually become the longest-running civil disobedience campaign since independence in 1962 (Kalyegira, 2011b) . No matter how small the numbers involved in the W2W and other protests, there is no denying their sheer intellectual brilliance. That brilliance was in their simplicity, in their ability to confer on the simplest of human activities, walking, and a major political significance: the capacity to say no (Mamdani, 2011) . It reflected the everyday experiences and struggles of a socially diverse and heterogeneous urban population. A4C called on middle class Ugandans to park their cars and join the W2W in order to bond with and show solidarity with the increasing number of people who had joined the ranks of hundreds of thousands of poor Ugandans especially the poor casual laborers, jobless, and the urban underclass that walk to work every day (Ddembe, 2011) . The protests focused on economic issues, but carried a strong political component in that they were organized by members of the opposition parties and mostly split across government/opposition lines (Helle & Rakner, 2014) . Mugisha (2011c) articulates this well;

We know that those who are afraid of demonstrations of compassion and empathy with our fellow human beings are those who have reason to fear. They are the ones with the power to provide solutions but they have neglected to use that power. Instead they will spend a quarter of our national budget on fighter jets to protect themselves from imagined enemies, even as our children go to sleep hungry. We shall measure our worth as a people and as individuals by seeing how many cared to walk in empathy and compassion with those in need. We shall know our determination and courage to face those who would besiege our city to keep us silent in the face of suffering. Our courage will come not from our individual determination but from our collective resolve to face our fears and conquer them.

The symbolic and practical meaning of the A4C mobilization of city residents is very important to be emphasized here. The political opposition keen to show they were concerned about people’s discontent-heeded the call to take part. Besigye, who, then was the head of the Forum for Democratic Change, announced that he and other opposition leaders would walk to work as a response to the call by A4C and that they had the right to do so (Aljazeera, 2011) . Having tapped state resources so freely to guarantee election wins for Museveni and the NRM, the government had been caught flat-footed, without enough money on hand to augment national gasoline reserves or take other steps to ameliorate the public’s distress―a distress that citizens all over Uganda could clearly trace to Museveni. It was a field day for Besigye and the opposition, and a massive embarrassment for the regime (Izama & Wilkerson, 2011) . Two other presidential contenders-DP leader Norbert Mao and Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) leader Olara Otunnu-were also highly visible. It was also supported by other opposition groups, and by a number of civil society organizations (including senior figures within the Church of Uganda. The group promised to respect laws by walking to their place of employment; walking together because it was their constitutional right to associate with those they pleased as long as they did not jeopardize the rights and freedoms of others. This was consistent with what the Shadow Attorney General lucidly indicated;

Nobody is going to intimidate us. What the government needs to do is to address the problems facing our economy and stop the blame game. There was nobody preparing Ugandans for an uprising, but if [current] conditions prevail the people would stand up. It was up to the government to make sure that such conditions didn’t prevail. Those people in government must address the problems in the country, ensure that there is democracy, stop mismanagement of public funds and promote good governance4.

The A4C on several occasions invoked the rights to free assembly and peaceful demonstration which are guaranteed under article 20 of Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 19 of the Civil political Rights Convention (ICCPR) to which Uganda is a signatory. The same right is recognized under Article 29(1) of the Uganda constitution which provides that every person shall have the right to (d) freedom to assemble and to demonstrate together with others peacefully and unarmed and to petition. This realization by Ugandans that they could take on the political establishment by simply walking to work defined, to some extent, how change could be achieved without waiting for the usually corrupt elective process to choose what they want (Masiga, 2012) .

As a struggle which had begun as a battle over social justice, W2W protests evolved a strong spatial strategy with an elaborate struggle for urban space opposing the sitting government. When freedom of expression was met with suppression and oppression, then opposition became the A4C’s position (Mukama, 2016) . As images of police torture were broadcast on television stations, and were posted on the internet, they triggered riots in various locations around Kampala. The city is a restive places where criminal violence is alarmingly common in ordinary times, with political violence ready to flare as well should a precipitating event (such as a fuel-price spike) be added to the already-volatile mix (Izama & Wilkerson, 2011) . The earliest incidents were reported from various central locations, including the densely populated areas around Kisekka Market, the Old Taxi Park and Lugogo Stadium. However, they soon spread to various outlying locations as well, including the areas around the FDC headquarters in Najjanankumbi, and various sites along the Entebbe road (the largest being at Kajjansi, which is about 20 km south of Kampala). Later, they also spread to Makerere University, as well as to various other urban centres around the country (including Masaka, Mbale and Mbarara). At each of these locations, scores of mostly young men set tires and cars alight, and fought running battles with police and the army. The protest walks always started in Kasangati, but ended up anywhere en-route to Kampala with ugly though somewhat glorious run-ins with the militarized police (Musaala, 2016) . The whole intention was to spatially articulate W2W demands by occupying city streets as the (then) Shadow Minister (then) for Internal Affairs indicated;

When those in government disagreed with those who were the government of the time, they chose to go to the bush [in 1980], our option is the streets5.

The suburbanization of the city gave the W2W another distinct spatial character. There was a marked decentralization of elements in A4C leading the W2W. While Kampala City remains functionally linked, A4C activities became increasingly fragmented into a complex mosaic of walkers, who practiced what Jansen (2001) described as “inserting” their bodies into non-accidental urban locations. Firstly, the protesters explicitly distinguished themselves from “villagers” (Jansen 2001), who for them epitomized obedience, political apathy and anti-citizenship. For as long as their actions could last, the protesters not only resisted arrest but were interested in gradually conquering new urban space from government authorities and undermining the capacity of the state to exercise surveillance. Furthermore, the protesters were interested in the most symbolic locations and spaces in the heart of Kampala City; preferably Constitutional Square, in what Jansen (2001) described as a strategy for “re-territorializing the city”. Through filling the urban space with walkers, sympathizers and noise, long marches, and traffic obstructions, the W2W protesters re-shaped the city; through minor and major inconveniences that redefined the nature of the urban space.

6. Surveillance Actions and (De) Construction of Citizenship

Six related areas of surveillance and response could be discerned including 1) urban securitization, arrest and detention of protesters; 2) (de) constructing protests and/as terrorism and treason; 3) urban space regulation and security zoning; 4) legal regulation of protests; 5) crackdown and censorship of the media; and 6) denial of the economic situation in the country. Although some of these actions were national in character, a large part of their deployment and visibility is in Kampala City.

6.1. Urban Securitization, Arrest and Detention of Protesters

Several security mechanisms of surveillance; watching and intelligence gathering in the city are part of what this paper calls the NRM security machine. The surveillance and securitization of demonstrations has become increasingly prominent. Citizen struggles have been grafted onto a pre-existing security infrastructure, which has evolved over many years in response to the threat of Baganda federalism and other forms of protest. The Buganda riots set the real ground for expression of disagreement with government and extreme reaction from the authorities, use of live ammunition against unarmed civilians. The memory of Tahrir Square fed opposition hopes, inspired and fueled government fears (Baker, 2015; Helle & Rakner, 2014; Mbazira, 2013) . For many in the opposition, Egypt had come to signify the Promised Land and for those in government, Egypt spelt a fundamental challenge to power, one that had to be resisted, whatever the cost (Mamdani, 2011) . From the beginning, the main story of W2W was the security forces’ markedly draconian response to the protests. A detailed description of police reaction is given in International Crisis Group (2012) , Kakuba (2015) , Kjaer & Katusiimeh (2012) but Odoobo-Bichachi (2012a) writes that the way the police had been programmed to react is that no political rallies would be allowed except with their permission.

The heavy-handed response bespoke a surprising lack of confidence for a government that had just secured a resounding re-election victory in 2011 (Conroy-Krutz & Logan, 2012) . Directly following his re-election for President in February 2011, Museveni firmly stated that he would not allow any protesting of any sort to occur in Uganda, as he did not want Uganda to become like other African countries. He forewarned political opponents and civilians alike that the harshest, firmest punishments would ensue for any such protesters (Feinstein, 2011) . The psyche of the police was to handle protesters as enemies and it seems it would take time and experience for the Ugandan police to realize that their job wasn’t to defend the regime against the people. The police would have running battles with protesters and the most egregious conduct of the police was in no uncertain terms, pointed at arresting and subsequent imprisonment of demonstrators. For civilians, supporters and skeptics alike, the sight of military resources deployed to maintain civil order in the streets, had come to blur the line between civil police and military forces as those in power insisted on treating even the simplest of civil protest as if it were an armed rebellion (Mamdani, 2011) .

Following the failure to anticipate and interpret the protests, the military police reacted to the mostly peaceful demonstrations with extreme and vicious violence, using pepper spray, plastic bullets, tear gas, and firing grenades indiscriminately at fleeing protesters and bystanders, injuring many (Baker, 2015; Izama & Wilkerson, 2011) . Consequently, the protests escalated; becoming protests against the police’s brutality, the right to demonstrate peacefully, the impunity and privilege of politicians, state’s neglect of the peoples’ needs and political corruption. In fact, Museveni knew that without controlling Kampala, his hold onto power was in balance and for Baker (2015) and Ssemuju (2012) , a city that had consistently voted against him; one of the fronts to control it was security. Rather than increasing a sense of security within newly built and regenerated places, the new focus of police policy encourages the formation of new governmentalities of insecurity and fear.

The details of persons arrested are appropriately captured by Lubwama (2012) but by and large, arrestees were charged with serious offenses including assault, incitement to violence, concealment of treason and treason (Helle, et al, 2011; Mbazira, 2013; Vasher, 2011) . In many cases, demonstrators using the public streets were barricaded in, severely restricted in their movements, kept away from the further movements or walking, and scores of youths who participated in the 2009 riots were put in prison for a period of over two years without trial (John Paul II Justice and Peace Centre, 2013) and many on charges thrown out subsequently by the courts for lack of prosecution evidence (Izama & Wilkerson, 2011; Lubwama, 2012) . The threat of detention without trial hanged heavy over the heads of the leaders of the protest movements and specific activists were targeted for the harshest measures so that others, it was expected would be frightened into silence. It was believed that the brutal crackdown would forever stop the protests and shock Ugandans back into their natural state of political detachment. In fact, NRM and its predecessors have always been principled forces battling opportunists (Museveni, 2011) . Emorut & Magara (2012) , Khisa (2016a) and Njoroge (2012) report that the Prime Minister and President promised that no one could disturb the “peace” of the country. They would crush arrestees and wipe out the political opposition to remind Ugandans that they had defeated armed gangs and despotic regimes in the past, and winning wars was the greatest achievement of the president in his curriculum vitae as a leader (Ampurire, 2016; Emorut & Magara, 2012; Guweddeko, 2013; Khisa, 2016a, Njoroge, 2012; Tumushabe & Rumanzi, 2016) and the remaining problem was dangerous liars, lawless civilians, lumpens and hooligans (Bisiika, 2016) .

Lawful assemblies were prohibited and the common excuse was that they destabilized the state, disrupted business, flows of production and well as the flow of goods and services in the City Centre. Makara, (2010) provides several grounds around which to reject this official or respected version of events considering that pro- NRM government assemblies were never dispersed. But images of children choking on tear gas, one brutally slain, and a man in bandages thrown behind bars just for walking to work were proving more powerful than the threat from the barrel of a gun (Gatsoiunis, n.d. In: Murumba, 2011 ).

The climax of the W2W protests was the violent and shameful arrest of FDC President Kizza Besigye. Led by a one Senior Police Officer Gilbert Bwana Arinaitwe with the help of a motley gang of security operatives, Besigye’s vehicle was intercepted at Mulago roundabout as he attempted to drive to town (Ddungu, 2011) . Using the butt of his pistol, Arinaitwe broke into Besigye’s vehicle before incessantly dousing the FDC leader with pepper spray (Ddungu, 2011; Mutaizibwa, 2012; Red Pepper, 2016) , temporarily blinding him (Acen, 2011) . Like a rehearsed Hollywood blockbuster scene, video footage captured a hooded man using a hammer to break the window of Besigye’s Land Cruiser vehicle. With remarkable ease, Arinaitwe later dragged Besigye out of the vehicle before bundling him on a patrol pickup (Ddungu, 2011; Red Pepper, 2016) . While the images of the attack were so grim and caused a public outcry, Arinaitwe was cleared of any wrong doing (Insider, 2014; Sunrise, 2015; Wasswa, 2015) and later promoted and redeployed to the Directorate of Crime Intelligence in the Uganda Police Force (Kato, 2016; Red Pepper, 2016) .

For a man whose political star and charisma was declining, these arrests gave him a second chance (Batanda, 2011) . This was manifested in the crowd present to welcome him from Nairobi and the largest demonstration was witnessed on May 12, 2011 on Besigye’s return from Nairobi on a day-long journey from Entebbe airport that overshadowed President Yoweri Museveni’s inauguration/swearing in ceremony on the same day. To the common man feeling disenfranchised, associating with him with a message of social protest represented their suffering (Batanda, 2011) . Attempts were further made by the 9th Parliament to ensure the Constitution was amended to deny bail to among others, suspected rioters and “economic saboteurs” until they had spent six months on remand (Naturinda, 2011; Butagira, 2012b) .

With the death of Police Constable Ariong during one of the demonstrations, a new platform to intensify repression of the A4C activists intensified. Police guidelines and surveillance approaches increasingly sought a spatial approach to control and regulation of the presence and absence of particular types of citizens in specific places at particular times. The geographical spaces including personal residences that A4C leaders relied on to organize were not haphazard or neutral locales in the Kampala urban landscape but they became sites of police deployment and targets of plain clothed security operatives to prevent the A4C leaders from leaving their homes. This interception of leaders in their homes; commonly referred as preventive arrest (home blockade and detention) was a common practice to deliberately frustrate the A4C. This preventive arrest was particularly acute and more pronounced with leaders of the opposition whose residences were frequently cordoned off by military and police officers when they attempted to walk to work. Preventive arrest’ is a law which the British colonialists used against Uganda several decades ago to conveniently leave protesters under house arrest until the police was confident that leaders would not engage in protests (Mugisha, 2011b) .

The massive recruitment and training of mercenaries by government to crack down on dissent was also proceeding apace. The security outfit that the government created in response to the W2W protests became so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knew how much money it cost, how many people it employed, how many surveillance programs existed within it or exactly how many agencies did the same work. In sum, the military doesn’t consist of one army, but of the Uganda Peoples Defence Forces and an increasing number of security organizations (Kjaer & Katusiimeh, 2012) . A quick stroll in Kampala City makes clear the Uganda security apparatus has adopted a more militarized language. The government has deployed security forces on almost every corner in every neighborhood in the city, like never before (Kagumire, 2011) . Butagira (2012a) questions whether the battery of security outfits, referred to elsewhere as terror squads clad in police uniform, whose members are mostly unknown to the public or even to one another are the new faces of terror across the city. Their manners are covert, if not unconventional or outright wayward. In fact, they dress shabbily to disguise their identity and always cover their eyes with dark glasses. For civilians, supporters and skeptics alike, the sight of armed police and military personnel (Figure 2) as well as fierce armored vehicles roaming the streets, deployed to maintain civil order on the streets, has come to blur the line between civil police and military forces as those in power insist on treating even the simplest of civil protest as if it were an armed rebellion (Mamdani, 2011) .

Omach (2010), Vasher (2011) and Titeca & Onyango (2012) explore the proliferation of vigilantes and plain cloth militias in Uganda’s politics but a stark observation is that a number of militias have sprung up to intimidate and coerce social identities into following government demands. Many Ugandans are still trying to get to the roots of two specific, massive unregulated, semi para-military vigilante groups of informal commandos/ goons called the Kiboko (stick) Squad and now Crime Preventers that often spring up on the streets in big numbers with long menacing sticks to clobber anybody trying to peacefully demonstrate. These plain clothed personnel armed with clubs, batons and canes have unleashed terror and beaten up people indiscriminately while the police standby and look on (Helle et al, 2011; Kigambo, 2011; Makara, 2010; Mulumba, 2011; WaMucoori, 2010) .

Although the Uganda Police Force refers to crime preventers as an extension of the historical Nyumba Kumi (Ten Houses) and politically neutral community policing arrangement, and not in any way a militia force; their recent large scale recruitment, hasty training and political sensitization, outside a clear legal framework cannot escape the scrutiny and suspicion that they will act in favor of the ruling party, the NRM (Titeca & Onyango, 2012; Observer, 2016; Ssekira, 2016) and enjoy its tacit official support (Omach, 2010) . The political opposition believed strongly that the government was fully behind these militia groups whose main duty is to disrupt political assembly and deny mobilization by the opposition political organs. Their presence was broadly perceived as adding to an intimidating pre-electoral atmosphere and strong militarization in the run-up to the elections (Titeca & Onyango, 2012; Insider, 2016) . As the country prepares for the 2016 Presidential elections, the political opposition has suggested that government was training crime preventers as a planned scheme to rig elections and intimidate people to vote the incumbent President Yoweri Museveni as well as beat people who were not supporting the National Resistance Movement and its candidates (Titeca & Onyango, 2012; Tugume, 2016) .

6.2. (De) Constructing Protests as/and Terrorism and Treason

The government has criminalized popular protests and rallies by opposition activists in a bid to silence all dissent and opposition to government’s policies and practices (Red Pepper, 2012) . Just like the 1945 and 1949 reactions by the colonial government, there grew an ill-founded conventional wisdom which held that the causes of the disturbances were essentially political: that their origins and course could be understood only by reference

Figure 2. Human forms of intelligence aimed at looking out for possible signs of trouble and averting them.

to the factional ambitions of a limited number of politicians (Thompson, 1992) . The W2W protests were not seen in the lenses of food, fuel prices and general economic well-being of larger sections of Ugandan society. By denying them official recognition, protesters remained invisible in policy and their visibility in the urban environment remained at the status of lunatics. Protesters have been linked to terrorist groups that are bent upon wreaking a legitimate government and posing a concomitant challenge to state sovereignty. In fact, immediately, after the first protest were dispersed, the police indicated that the members of opposition parties were trying to use demonstrators as part of a wider ploy and political move that was psychologically preparing the public for an armed insurrection to overthrow a duly elected and legitimate government (Kagumire, 2011) .

The IGP would issue terror alerts frequently to justify the continued presence of armed men in the city and of course every road roundabout and other important road junctions have what is now termed as a permanent military barracks or security cordon. Accusations by the IGP in the media indicated that A4C was spreading sectarian propaganda and training youths in terror tactics and police had information that there were training youths in Afghanistan by the Taliban and Al Qaeda and, some of whom had already infiltrated into the country (Athumani, 2011) . The IGP added that other youths in Kenya were in the process of being smuggled into the country (Kampala Dispatch, 2011) although these allegations were ridiculed by the public and soon lost traction (Mugisha, 2011b) .

It was further claimed that the opposition was portraying the government as illegitimate, claiming the NRM rigged the February 18th, 2011 general elections, and as such was opportunistically pressing for power-sharing (Mugerwa & Naturinda, 2011) . Mamdani (2012) reminds us that once in power, armed guerrillas have tended to be distrustful of independent popular activity, indeed of anyone who claims to have a different understanding of what the nation needs. That accusation seemed to gain credence from the utterances made by Besigye on his campaign trail in the run-up to the February 18th, 2011 presidential elections that he lost to Museveni. He indicated that he would not go to court as on previous occasions but use other means to fight an illegitimate government. The police were vindicated when according to Twinoburyo, (2011b) , Democratic Party President Norbert Mao, speaking on behalf of four of his counterparts-Kizza Besigye (FDC), Olara Otunnu (UPC), Asuman Basalirwa (JEEMA) and Mabikke (SDP), said;

“We have concluded collectively that this is a broad struggle-whether it is teachers, boda bodas, taxi drivers, traders, political parties, students and lecturers-we are all together in this struggle,” and that “a change of government is a clear goal that we are pursuing”.

This was consistent with what other leaders of the FDC indicated in their public rallies. Kitaka Kaaya (2012) , for example, captured the sentiments of the Head of the FDC Women League;

I was jailed for two months at Luzira because Museveni claimed that I was plotting to remove him from State House. I want to clearly state it here that my biggest programme is that of removing Museveni and his thieving regime from power! I want to assure you that I no longer sleep; my daily programme is to overthrow President Museveni! This is provided for in the constitution, and I will not tire until we have achieved it.

6.3. Urban Space Use Regulation and Security Zoning

The W2W protests practiced those identifiable patterns of citizenship and the consequence of this practice was the profound alteration of the urban space. W2W protests emerged as instrumental in city residents’ confrontation with the regime; it materialized to remind urban dwellers that urban public spaces were political arenas as much as they were pavement and asphalt. The use of military hardware to control city spaces and transport corridors, and issues regarding policing of the city in what is commonly referred to as unprecedented Ugandan peacetimes have dominated media reports. A number of critics describe how a hyper-securitization or militarization of the urban environment tends to filter users into oppositional categories, thus limiting the accessibility of spaces to only those deemed desirable or appropriate (Mitchell, 2003; Németh, 2010) . The W2W protesters were dismissed because they encroached on public space; the streets and also encroached on other public spaces and business areas in the city as the government would claim. The police and other security forces intensified spatial regulation of social and economic behavior by invoking several edicts against the use of “popular spaces”; the areas in which the city population come together. Even before the terror attacks, owners and managers of high- profile public and private buildings begun to militarize spaces by outfitting surrounding streets and sidewalks with rotating surveillance cameras, metal fences and concrete bollards.

As long as W2W protesters were perceived as idle and disorderly on public space and the city in general, they were easily and sporadically eradicated from city spaces. In sum, there was a shift from general city space planning to spatially targeted and place-focused restrictions in the use of urban space in the city. Targeting interventions especially police blockades to geographically circumscribed areas further away from the Central Business District activities was presented as a path to remedy further protests and reduce their potential destructive effect. A quantifiable indicator on the frequency of public space closures, amount and intensity of physical space declared and lost for security zones/landscapes was beyond the scope of this paper, but a significant amount of city physical space has now been closed off from the public for security purposes.

Prior to the protests, regulation of use of urban space was purely a KCCA function and was administered through city physical planning guidelines. Mounting political pressure on KCCA and the accompanying protests in the city have resulted in a series of ordinances and Acts which have transferred responsibility for use of space to the Uganda Police Force. Several public spaces across the city have now become, what Nemeth (2009) refers to as closed or limited use anti-terror security zones with their related behavior and access controls. Five years after the protests, significant parts of the Kampala City Central Business District remain largely sealed off as “security zones.” Some of these are illustrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4 but the most important space is Constitutional Square. It has completely been sealed off from public access and it is now dotted with gun wielding persons and armored vehicles stationed preparing for any potential threat. KCCA has argued that the use of Constitutional Square and nearby grounds was regulated by KCCA but the Uganda Police Force and several security/military outfits being in-charge of law and order were actually in-charge of the grounds.