Health

Vol.5 No.6A3(2013), Article ID:33390,7 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.56A3005

Developmental assets and age of first sexual intercourse among adolescent African American males in Mobile, Alabama

![]()

1College of Health, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, USA

2Division of Allied Health, Indiana University, Kokomo, USA; *Corresponding Author: henderje@iuk.edu

3Graduate Studies, Western Oregon University, Monmouth, USA

4School of Public Health, University of Alabama, Birmingham, USA

Copyright © 2013 Shannon Talbott et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 7 April 2013; revised 7 May 2013; accepted 1 June 2013

Keywords: Developmental Assets; Adolescence; Sexual Behavior; African American Males

ABSTRACT

Background and Aims: Younger age at first sexual intercourse is associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes. We aimed to gain a clearer understanding of a wide range of individual, family and social factors that may influence sexual behavior of children and adolescents. Specifically, we examined the relationships of developmental assets with age of first sexual intercourse among a large sample (n = 1061) of adolescent African American males living in low-income neighborhoods in Mobile, Alabama. Methods: Using the Developmental Asset Model as a theoretical guide, we selected variables from adolescent survey data and conducted logistic regression analysis to determine predictors of early age of first sexual intercourse. Results: Nearly one half (49%) of the male survey participants reported that they first had sexual intercourse at the age of 12 or younger. The total number of assets was the strongest predictor of later age (13 years old or later) of first sexual intercourse (OR 1.49, 95% CI = 1.09, 2.04), followed by decision-making skills (OR 1.40, 95% CI = 1.04, 1.86), and positive view of the future (OR 1.36, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.74). Conclusion: There are several developmental assets related to the age of first sexual intercourse. This study found support for the Developmental Asset Model as a framework for promoting sexual and overall adolescent health. Recommendations for asset-building among this population are discussed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Unplanned teen pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are commonly recognized public health concerns. For example, teen parents are less likely to complete high school and they and their infants are more likely to live in poverty [1]. Even though the teen birth rate reached a historic low in 2010, the US still has the highest rate among comparable countries and costs almost $11 billion per year [2]. STIs costs the US another $17 billion in health care annually and sexually active teens are at higher risk [3]. In addition, the HIV/AIDS incidence in the general population in the US has persisted at about 50,000 new cases each year, and young adults and teens continue to be at risk [4].

Given these enduring public health concerns and the current political and social controversy regarding sex education, it is crucial to develop a clearer understanding of factors related to teen sexuality [5,6]. Traditionally teen sex behavior has been conceptualized in a riskbased framework [7], particularly in the areas of teen pregnancy and STIs. Risk factors for teen pregnancy and/or STIs cited in the literature have included: substance abuse, stronger risk-taking attitudes, male dominance, risky peer norms, being away from home for long periods, and dropping out of school [8,9]. This approach focuses on negative factors of teens that need to be “fixed”, rather than focusing on potentially positive strengths, or assets, that may be important for healthy teen sexuality.

1.1. The Developmental Asset Model as a Conceptual Framework to Guide Research

The Developmental Asset Model is a strength-based approach based on 40 developmental assets important for healthy development for middle school and high school adolescents and was developed by the Search Institute [10]. This framework proposes that research into youth health behaviors should not just be about risk factors, but should include protective factors (assets). The 40 assets, also known as “building blocks”, that protect youth from risky behaviors include 20 external assets such as family support, caring school climate and adult role models, and 20 internal assets such as school engagement, self-esteem and resistance skills [11]. In general, this model asserts that the more assets a young person has, the less likely the youth will engage in risky health behaviors such as violence, alcohol/drug use and early sexual intercourse. In fact, the developmental assets may explain 20% - 30% of risk behaviors over and above demographic factors [12].

Several studies have shown that developmental assets have a protective effect on risky sexual behavior. A higher total count of assets has been correlated to delayed sexual intercourse [13,14]. The external assets of family support and maternal/paternal support have been consistently related to less sexual risk among adolescents [15-18]. In addition, the internal asset of future aspirations and the external assets of both school support and peer support were each associated with less risky sexual behaviors [15,16,19].

1.2. Timing of Initial Sexual Intercourse

Youth who experience initial sexual intercourse at an early age may have an increased chance of long-term health concerns, negative behaviors, and lowered selfesteem and family quality [20-22]. One study found that 81% of youth who experienced first sexual intercourse between the ages of 12 - 15 years wished that they had waited longer to have sex [23].

African American males have sexual intercourse at an earlier age than other male racial groups [24]. In a study of 847 adolescent males, it was found that 44% of African American males reported that their first sexual intercourse was by the age of twelve, compared to 12% of white males [25].

Although there have been numerous studies published on the relationship between various developmental assets and sexual behaviors among coed and/or female adolescents, very little is known about the developmental assets that may be associated with the age of initial sexual intercourse among young African American males. The present study fills this gap and can provide specific targets for asset-building. The purpose of this study was to examine youth assets and their association with age of initial sexual intercourse among a large population of young African American males living in low-income neighborhoods in Mobile, Alabama.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

The participants for this study were obtained from a subset of data from the Mobile Youth Survey, a large survey of children 10 - 18 years old living in the most impoverished neighborhoods in Mobile, Alabama [26]. Thirteen neighborhoods were targeted (seven in public housing and six in non-public housing) and in these neighborhoods the median household income was less than $12,000 and about 95% were African American. Half of the households with children between 10 and 18 were randomly selected for the study. The present study focused specifically on the data from African American males 13 to 18 years old.

Internal Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the University of Alabama in Birmingham and Western Oregon University.

2.2. Procedures

Written parental consent was obtained by trained interviewers at the home of each youth in this study. The refusal rate was only nine percent. Adolescents were scheduled for a time for a group survey administration at numerous locations such as nearby churches, community centers or schools in the neighborhood. The group interviews ranged from 3 to 40 adolescents at a time, with an average of 22 per group. If the adolescents were not able to make it to a group administration, they were given inhome interviews; about 20% of the youth were interviewed in their homes. The overall response rate was 85%.

During the survey administration, the questions were read aloud by one of the trained interviewers, and each participant then marked the answers in his/her survey books. If a youth in a group survey needed more time, he/she was taken to a separate room and given the survey one-on-one. Adolescents who completed the survey received $15.

2.3. Survey Instrument

The survey consisted of 406 multiple choice questions about health-related behaviors, circumstances and assets, attitudes, and demographics. Most of the 406 survey questions were adapted and/or modified from existing questionnaires [27].

2.4. Measures

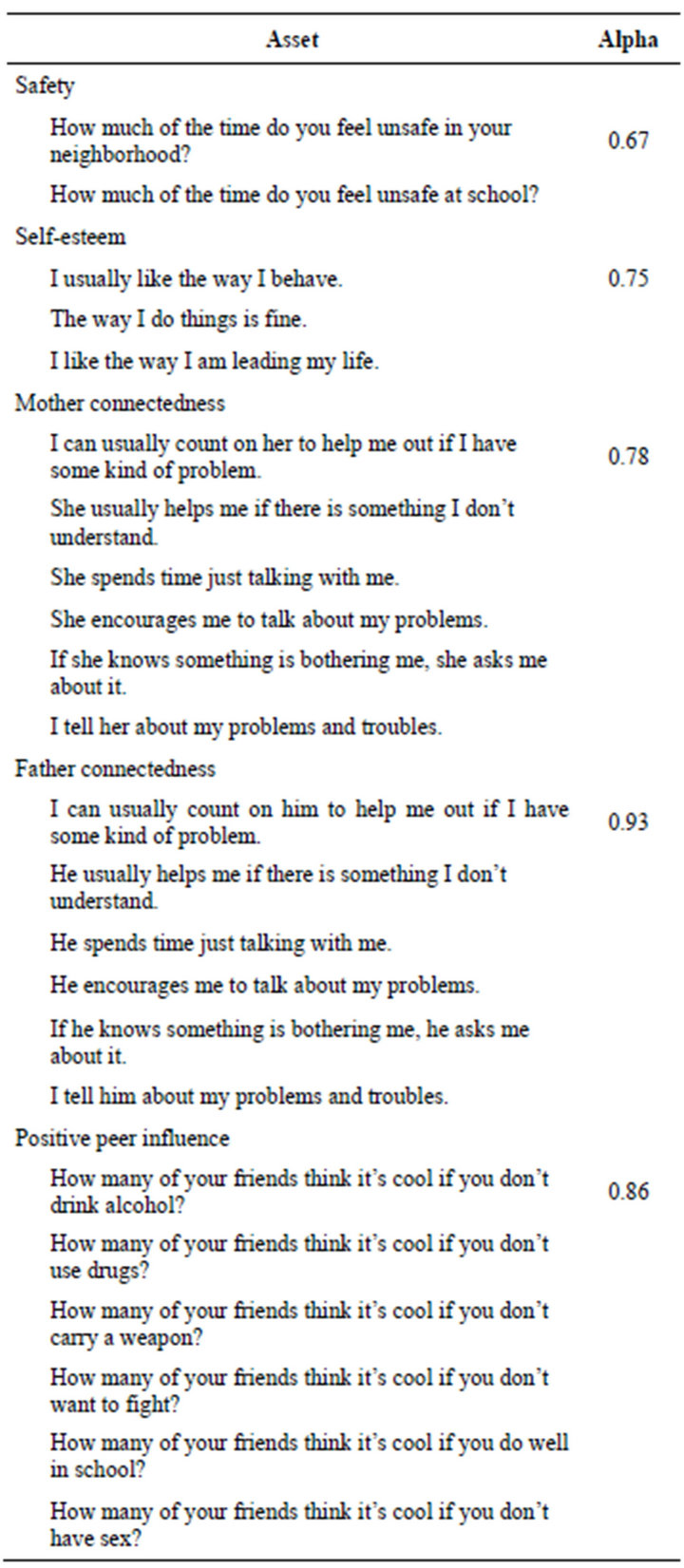

Using the Developmental Asset Model as a general framework, we were able to identify nine external assets and four internal assets that were measured from the total 406 survey questions. Assets that were measured by a single-item question are listed in Table 1 and include religious community involvement, high expectations, youth programs, homework, decision-making skills, school connectedness, positive view of the future, and community values youth. Five more assets (safety, selfesteem, mother-connectedness, father-connectedness, and positive peer influences) were measured using composite variables. Cronbach’s alpha for each measure ranged from 0.67 - 0.93, which was adequate to very good reliability (Table 2).

2.5. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable was age at initial sexual intercourse. Participants were asked, “How old were you when you first had sexual intercourse?” Participants were told that “Sexual intercourse means having sex with the male’s penis inside the female’s vagina. This is sometimes called ‘going all the way’”. This survey item was collapsed into two categories: 1) those who were aged 12 years or younger at first sexual intercourse, and 2) those who were 13 years or older at first sexual intercourse and those 13 or older who had not yet had sexual intercourse at the time of the interview.

2.6. Data Analysis

In order to determine the relative importance of the assets that was significant (p < 0.05) with correlation ana-

Table 1. Developmental assets measured with single item survey questions.

Table 2. Assets measured with composite variables and Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient.

lysis with age at first sexual intercourse, logistic regression was performed with “early/later age at first intercourse” (a dichotomous measure) as the dependent variable. The logistic regression included all 13 assets (0 = did not have asset; 1 = had asset) as well as a 14th variable of “total number of assets” with a value of 0 - 13. SPSS 15.0 (for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to perform all analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample Characteristics

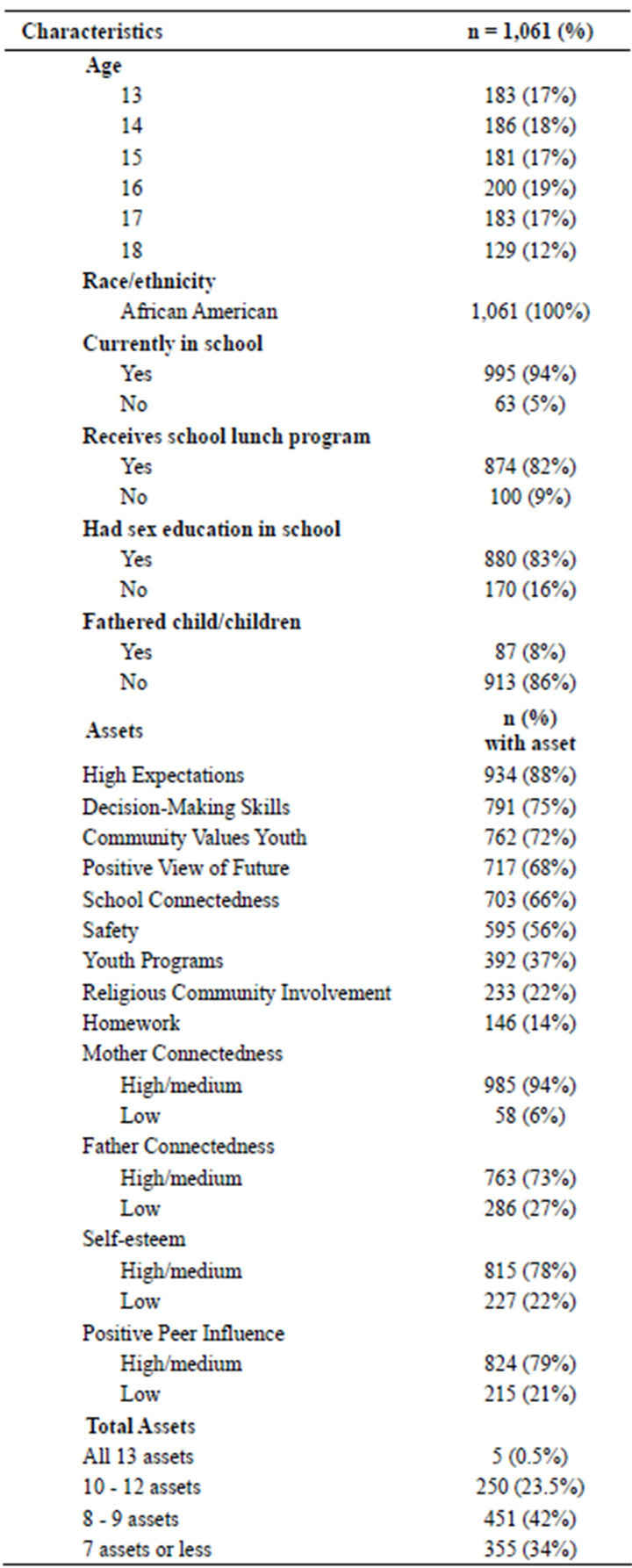

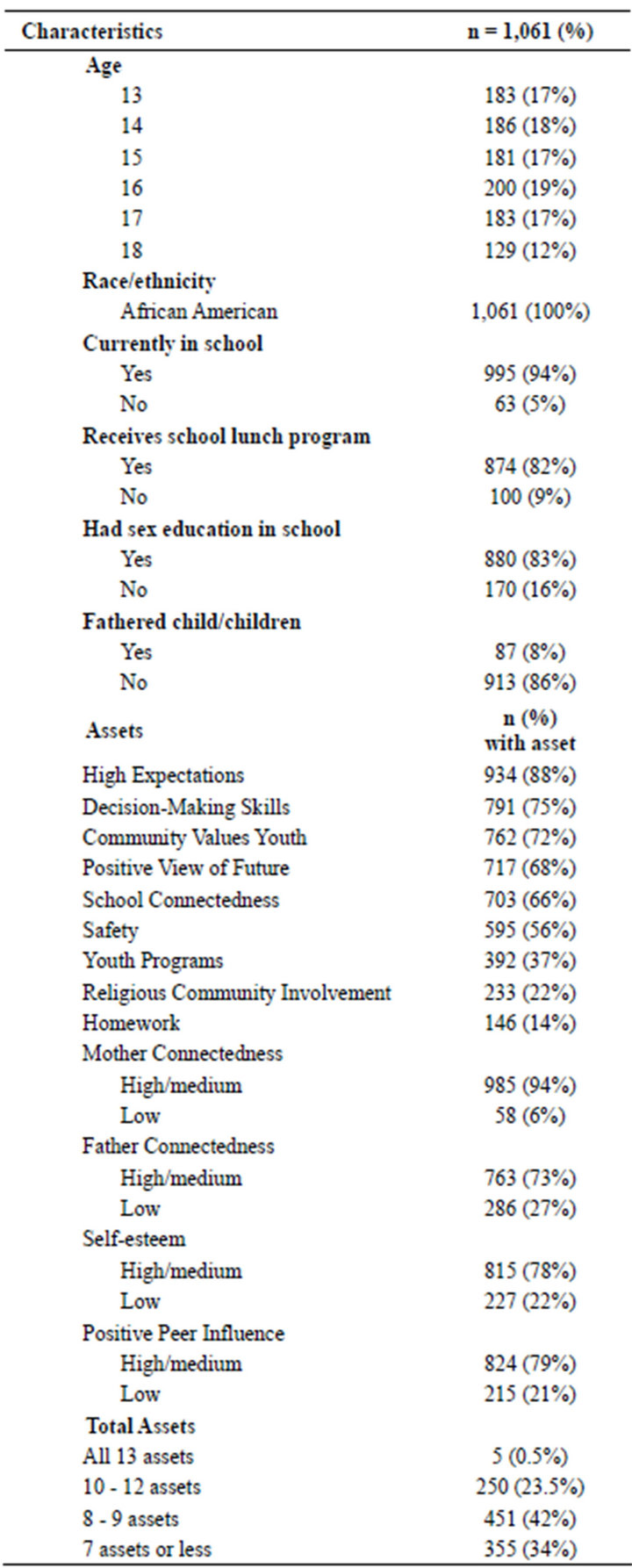

From the 3682 youth contacted for an interview, 3113 participated in the survey. There were a total of 1061 African American males between the ages of 13 - 18 years in this study. The mean age was 15.4 years and the majority (94%) was enrolled in school (Table 3). Over 80% of the males reported that they had received free/reduced cost lunch at school. Almost one half (49%) reported having sexual intercourse during pre-adolescence, at 12 years or younger. Eight percent of the males 13 - 18 years old reported that they had fathered a child.

3.2. Assets

Less than 1% of the male participants reported having all 13 of the assets (Table 3). The most common asset was mother connectedness, with 94% of the males reporting high/medium support from their mother and 73% feeling connected to their fathers. Only a little over half (56%) reported feeling safe at both school and in their neighborhood. The majority (75%) reported good decision-making skills and two-thirds of the males had a positive view of the future, feeling hopeful and optimistic. The least common asset was homework, with only 14% of the males reporting one hour or more of homework in the evenings.

3.3. Analysis

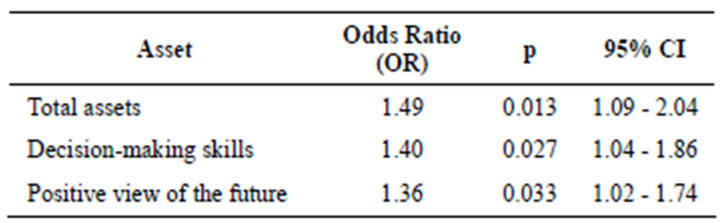

Correlation analysis suggested that four assets were significantly associated (p < 0.05) with age at initial sexual intercourse: total number of assets (r = 0.11), decision-making skills (r = 0.10), positive view of the future (r = 0.09), and high expectations (r = 0.07). Age at first sexual intercourse was not significantly associated with belonging at school, father connectedness, mother connectedness, self-esteem, religion, safety, after school activities, homework, positive peer influence, or community value for youth.

3.4. Predictors of Age of First Sexual Intercourse

When the four potential predictor assets were examined in a logistic regression model, results suggested that three developmental assets were significant to timing of first sexual intercourse: total number of assets (OR 1.49, 95% CI = 1.09, 2.04), decision-making skills (OR 1.40, 95% CI = 1.04, 1.86), and positive view of the future (OR 1.36, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.74) (Table 4). The asset of high expectations (mother pushes him to do his best) did not reach the likelihood ratio test p < 0.05 significance

Table 3. Sample characteristics and assets.

level and therefore was removed from the model. Overall, African American adolescent males who first had sexual intercourse later (≥13 years) were more likely to have had more total assets, report that they usually made good

Table 4. Assets that predicted later age of initial sexual intercourse among African American adolescent males.

decisions, and felt hopeful and optimistic about the future.

4. DISCUSSION

In this sample of African American males aged 13 - 18 years old from Mobile, Alabama, one-half reported that they first had sexual intercourse before the age of thirteen. In addition, almost one-in-ten (8%) reported that they had fathered a child. These results illustrate the need to develop a clearer understanding of factors related to adolescent male sexuality.

This is the first study to reveal the relationships of youth assets with age of first sexual intercourse among a large sample of adolescent African American males. Findings from this study were supportive of the Developmental Asset Model [11]. Adolescent African American males with more total assets were less likely to have sexual intercourse before the age of 13 years. This research supported prior research on sexual health which demonstrated in samples of female adolescents and female/male adolescents that more total assets were a protective factor for delayed engagement in sexual activity [13,14,16]. Only one-fourth of the males in our study had 10 or more of the 13 measured assets. One-third of the males were considered “asset poor” in this study.

In addition to the total number of assets, our study found that two specific assets, decision-making skills and positive view of the future, independently had protective effects on age at first sexual intercourse. Other researchers have also found that decision-making skills and positive view of the future were associated with healthier sexual behavior among adolescents [18,28,29].

The primary implication of this study is that assetbuilding for young males should be a central goal of families, communities, and educational programs. Aiming for a community of “asset rich” youth is a promotion not only of healthy sexuality but general health and well-being as well. Adolescent African American males may be the group who has the most to gain from families, communities and schools that focus on building assets.

The three least common assets among the males in this study were youth programs, religious community involvement, and homework. These three areas might be a good place to start with asset building. For example, youth programs such as sports, clubs and organizations that engage young males would be considered an assetbuilding activity by a community. Furthermore, community-based youth programs could focus on what the adolescents need to do, as opposed to not what not to do [30].

In our study, the vast majority (92%) of the males reported that religion was important or somewhat important to them, yet only 22% of them had the asset of religious community involvement. Oman and others found that religious community involvement was an important asset for adolescents [13]. New, relevant and interesting gender-specific and culture-specific programs in this area would most likely increase religious community involvement and serve as another asset for these youth.

School is a crucial component of asset building in youth. Homework was the least common asset in our study: only 14% of the male students reported that they did one hour or more of homework each school day. More time on homework is an asset itself, and contributes to building other assets such as school engagement, bonding to school, and reading for pleasure [12].

Families and school programs can also influence the two assets found in our study to be individual predictors of age of first sexual intercourse among adolescent African American males: decision-making skills and positive view of the future. The majority of adolescent males in this study reported that they had sex education classes, but there is a need to go beyond the traditional sex education format. Health teachers and other teachers should assess their students’ general decision-making skills in order to provide appropriate opportunities to improve sexual decision-making and gain this developmental asset. In addition, the costs and benefits of sexual decision-making should be discussed in classrooms, not only in terms of health risks, but in terms of the student’s view of the future. Sexual health programs that focus on general decision-making skills and positive views of the future, within the context of the developmental asset framework, could enable male students such as those in our study to not only form explicit knowledge about the costs/risks/benefits of sex, but to acquire assets that could ultimately have a positive influence on other healthrelated behavior.

The primary limitation of this study is that the data are self-reported. Bias may occur, especially when reporting sexual behavior. However, data from a national survey given to sexually-active teens showed that males were more consistent than females in reports of sexual behaviours [31]. Furthermore, it was shown that reliability of self-reported data was enhanced when the survey included definitions of sexual terms, the use of non-technical jargon, and a focus on short term recall [32]. Knowledge of confidentiality by survey participants can reduce potential bias [29]. All of these criteria were included in our study.

In conclusion, our study shows the need for increased assets among African American male youth, with specific emphasis on the assets of decision-making skills and positive view of the future. By joining together and implementing the framework of the Developmental Asset Model, communities, parents, and schools can help adolescent males acquire the assets that influence sexual behavior as well as cultivate healthy and productive adult men.

REFERENCES

- Singh, S. and Darroch, J.E. (2000) Adolescent pregnancy and childbearing: Levels and trends in developed countries. Family Planning Perspectives, 32, 14-23. doi:10.2307/2648144

- Hamilton, B.E. and Ventura, S.J. (2012) Birth rates for US teenagers reach historic lows for all age and ethnic groups. NCHS Data Brief, No. 89, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) HIV surveillance report, 23. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports

- McKee, J. (2010) GOP using sex-ed controversy as election issue. Independent Record, 23 July 2010. http://helenair.com/news/article_2a309d24-9621-11df-ad10-001cc4c03286.html

- Beshers, S. (2007) Abstinence—What? A critical look at the language of education approaches to adolescent sexual risk reduction. Journal of School Health, 77, 637-639. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00244.x

- Thom, B., Sales, R. and Pearce, J.J. (2007) Growing up with risk. The Policy Press, Bristol. doi:10.1332/policypress/9781861347329.001.0001

- Voisin, D.R., DiClemente, R.J., Salazar, L.F., Crosby, R.A. and Yarber, W.L. (2006) Ecological factors associated with STD risk behaviors among detained female adolescents. Social Work, 51, 71-79. doi:10.1093/sw/51.1.71

- Thompson, S.J., Bender, K.A., Lewis, C.M. and Watkins, R. (2008) Runaway and pregnant: Risk factors associated with pregnancy in a national sample of runaway/homeless female adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 125-132. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.015

- Leffert, N., Benson, P.L., Scales, P.C., Sharma, A.R., Drake, D.R. and Blyth, D.A. (1998) Developmental assets: Measurement and prediction of risk behavior among adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 2, 209-230. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0204_4

- Search Institute (2011) 40 developmental assets for adolescents. http://www.search-institute.org/developmental-assets

- Scales, P. and Leffert, N. (1999) Developmental assets: A synthesis of scientific research on adolescent development. Search Institute, Minneapolis.

- Oman, R., Vesely, S., Aspy, C., McLeroy, K. and Luby, C. (2004) The association between multiple youth assets and sexual behavior. American Journal of Health Promotion, 19, 12-18. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-19.1.12

- Doss, J., Vesely, S., Oman, R., Aspy, C., Tolam, E., Rodine, S. and Marshal, L. (2006) A matched case-control study: Investigating the relationship between youth assets and sexual intercourse among 13- to 14- year-olds. Child Care, Health and Development, 33, 40-44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00639.x

- Rink, E., Tricker, R. and Harvey, S. (2007) Onset of sexual intercourse among female adolescents: The influence of perceptions, depression, and ecological factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 398-406. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.017

- Evans, A., Sanderson, M., Griffin, S., Reininger, B., Vincent, M., Parra-Medina, D., Valois, R. and Taylor, D. (2004) An exploration of the relationship between youth assets and engagement in risky sexual behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 424e21-424e30.

- Parera, N. and Suris, J.C. (2004) Having a good relationship with their mother: A protective factor against sexual risk behavior among adolescent females. Journal of Pediatric Adolescent Gynecology, 17, 267-271. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2004.05.002

- Fulkerson, J., Story, M., Mellin, A., Leffert, N., NeumarkSztainer, D. and French S. (2006) Family dinner meal frequency and adolescent development: Relationships with developmental assets and high-risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 337-345. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.026

- Mueller, T., Gavin, L., Omen, R., Vesely, S., Aspy, C., Tolma, E. and Rodine, S. (2010) Youth assets and sexual risk behavior: Differences between male and female adolescents. Health Education and Behavior, 37, 343-356. doi:10.1177/1090198109344689

- Sandfort, T., Orr, M., Hirsch, S. and Santelli, J. (2008) Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: Results from a national US study. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 155-160. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.097444

- Bingham, C.R. and Crocket, L.J. (1996) Longitudinal adjustment patterns of boys and girls experiencing early, middle and late sexual intercourse. Developmental Psychology, 32, 647-658. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.647

- Herold, E.S. and Goodwin, M.S. (1979) Self-esteem and sexual permissiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 908-912. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(197910)35:4<908::AID-JCLP2270350444>3.0.CO;2-1

- Albert, B. (2005). Fact sheet: Not just another single issue: Teen pregnancy prevention’s link to other critical social issues. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, Washington DC.

- Roche, K., Mekos, D., Alexander, C., Astone, N., RocheBandeen, K. and Ensminger, M. (2005) Parenting influences on early sex initiation among adolescents: How neighborhood matters. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 32- 54. doi:10.1177/0192513X04265943

- Springer, P., Ketring, S.A., Hibbert, J. and Salts, C.J. (2008) Timing of initial sexual intercourse as a mediating factor between white and black adolescent’s sexual attitudes and sense of self. Adolescent and Family Health, 4, 75-83.

- Bolland, J. (2007) Mobile youth survey overview. School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham. http://www.ches.ua.edu/news/mys_description.pdf.

- Bolland, J. (2003) Hopelessness and risk behavior among adolescents living in high-poverty inner-city neighborhoods. Journal of Adolescence, 26, 145-158. doi:10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00136-7

- Harris, L., Oman, R., Vesely, S., Tolma, E., Aspy, C., Rodine, S. and Marshall, L. (2006) Associations between youth assets and sexual activity: Does adult supervision play a role? Child Care, Health and Development, 33, 448-454. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00695.x

- Oman, R., Vesely, S. and Aspy, C. (2005) Youth assets and sexual risk behavior: The importance of assets for youth residing in one-parent households. Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health, 37, 25-31. doi:10.1363/3702505

- Doswell, W. (2000) Promotion of sexual health in the American cultural context: Implications for health promotion in school age African-American girls. Journal of National Black Nurses Association, 1, 51-57.

- Upchurch, D., Lillard, L., Aneshensel, C. and Fang, L. (2002) Inconsistencies in reporting the occurrence and timing of first intercourse among adolescents. The Journal of Sex Research, 39, 197-206. doi:10.1080/00224490209552142

- Schrimshaw, E., Rosario, M., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. and Scharf-Matlick, A. (2006) Test-retest of self-reported sexual behavior, sexual orientation, and psychosexual milestones. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 225-234. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-9006-2