Beijing Law Review

Vol.07 No.01(2016), Article ID:64304,9 pages

10.4236/blr.2016.71005

Subnational Fiscal Autonomy in a Developmental State: The Case of Ethiopia

Zemenu Yesigat1,2,3

1Haramaya University, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia

2Constitutional and Public Law, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

3College of Law, Dire Dawa University, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 2 January 2016; accepted 6 March 2016; published 9 March 2016

ABSTRACT

Due to different factors, federations exhibit significant variation in their respective forms, natures and degrees of decentralization. Regardless of these differences, however, the necessity of a federal covenant, which bestows genuine autonomy on subnational governments, is not contested. Indisputably, a mere constitutional stipulation does not guarantee the financial autonomy of subnational governments as the latter is influenced by the political economy narratives of a government. Though the fallings of Ethiopian “developmentalism” on the effective functioning of the federal system are multifaceted, this article scrutinizes its impact on the fiscal (tax) autonomy of subnational governments. Looking at the contemporary “developmental-oriented” measures of the federal government vis-à-vis the constitutionally dictated autonomy of regions to generate own-source revenue, the article argues that the fiscal autonomy of subnational governments is highly constrained due to the adoption of the developmental state paradigm.

Keywords:

Fiscal Federalism Ethiopia, Developmental State, Subnational Fiscal Autonomy

1. Introduction

In spite of the ever growing debate on the economic rationale for decentralization, the issue of fiscal federalism has become more of a political issue of self determination than a matter of public welfare (Prud’homme & Shah, 2002) . Like many federations, the post-1991 state restructuring measures and the Ethiopian “ethnic federalism”1 were not offshoots of the quest for economic development. Many agree that federalism was rather the best, perhaps the only measure of the time that was taken for the survival of the country with the view of balancing the forces of unity and diversity (Assefa, 2007; Fasil, 1997) .

The Ethiopian federal system, as initiated in the Transitional Charter2 and reaffirmed by the 1995 Constitution of Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia3, has introduced legislative, administrative and fiscal decentralization endeavoring to assure the right to self-administration, the cornerstone of the federation. Similar to most federations, however, fiscal federalism in the Ethiopian system is characterized by mismatches between the expenditure needs and revenue capacities of subnational states, commonly referred as vertical imbalance.

Overwhelming level transfer dependency, accompanied by vague provisions in the Constitution regarding concurrent powers as well as the lack of formal system of Inter Governmental Relation (IGR), troublesomely run the Ethiopian fiscal federalism. In other words, even if the risky fiscal imbalance can be primarily blamed for the erosion of the budgetary autonomy of regional states, the budgeting process is mainly influenced by the national socio-economic and developmental plans and programs which do not “permit much deviation from the dictates of the center” (Keller, 2002) .

The ruling party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Party, has been criticized for overlooking the federal arrangement mainly because of its internal structure of “democratic centralism” and its ideology of “revolutionary democracy” (Abbink, 2012) . The party has gone through several periods characterized by contrasting ideological paths in the past two decades. Abbink (2012) summarizes these changes into four phases. The first phase, from 1991 to 2000, was a period of transition and stabilization followed by nationalist reconfiguration of 1998-2003, in the aftermath of the Ethio-Eritrean war and the Tigrean People Liberation Front’s (TPLF) split of 2001. The remaining two phases were the incorporation of affiliate parties broadening the party, which took place around 2003 to 2005 while the developmental state paradigm has been adopted since 2005.4

Some scholars argue that the historical rise of “developmental states” traces its roots back to the late 16th Century Europe (Bagchi, 2004) . However, the “developmental state paradigm” had gloomed as the strong and persuasive argument for the East Asian success that marked the emergence of the new field of scholarship thereof. Nevertheless, the view that perceives the state as an engine for economic development predates the idea of Developmental State (DS) as a “novel” school of thought and emerging field of scholarship.

Despite significant variation among the existing works in the field regarding its meaning, most, if not all scholars recognize the ideological and structural components of the developmental state. In light of the ideology-structural nexus, a developmental state can be discerned as, “[a] state that puts economic development as the top priority of governmental policy and is able to design effective instruments to promote such a goal” (Bagchi, 2000) . The ideological element is related to a government’s firm stance on making economic development its top priority. Developmental orientation is the distinguishing feature of developmental states elevating economic development above all other policies. With economic growth as its primary goal, a “developmental” state cannot also be a regulatory or welfare state one (Johnson, 1982) .

Ideological orientation alone does not make a state developmental unless it also has the capacity to implement its policy objectives. A state-structure appears to be the crucial factor in determining the success or failure of a developmental state as it is the ability to mobilize the nation which matters more than its economic policy. State structure is synonymous with “state capacity”, which is comprised of the ability of a state to prioritize, policymaking and planning as well as its capacity to mobilize resources towards national goals (Doner, 2005) .

Some scholars argue that the Developmental State (DS) of Ethiopia is a recent phenomenon introduced in the aftermath of the 2005 popular election (Messay, 2011) . Contrary to this scholarly argument, documents prepared by the government and/or the ruling party invoke the paradigm was one of the reasons for the TPLF split in 2001 (Meles, 2006) . According to these documents, the conception of the DS paradigm dates back to the late 1990s reaching full articulation around 2000 and 2001 (Messay, 2011) .

The developmental state from its very essence claimed to defeat the idea of federalism (Rao, 2006) . This postulation is supported by the fact that the period of developmentalism coincides with increasing centralization in a number of federal systems, including Brazil and India (Thakur, 1995; Castanhar, 2003) . The objective of this study is, thus, to scrutinize the nexus of the impact of the developmental state paradigm on the taxation powers and the volumes own-source revenues of regions, together with the trend toward vertical imbalance in the federation.

2. Fiscal Federalism and Subnational Autonomy: A Brief Note

2.1. Fiscal Federalism

Fiscal federalism covers matters involving constitutional arrangements that assign expenditure responsibilities and revenue raising capacities, as well as the mechanisms for adjusting horizontal and vertical imbalances. Fiscal federalism is, therefore, a study of the allocation of legislative and executive responsibilities as well as taxation powers among different layers of a government.

Expenditure responsibility can be discerned from in the division of legislative and executive powers among different tiers of a government in a federal system. Likewise, there are allocations of exclusive as well as shared and residual powers of legislation in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) Constitution. For instance, apart from reserving residual powers for States, the Constitution bestows them with powers to make or amend their respective constitutions as well as to issue and implement socioeconomic development policies, strategies and plans. Shared powers in the Ethiopian federal system could appear either in the form of concurrency or framework powers.

As a general rule, the FDRE Constitution adopts a dual model of allocating legislative and executive powers. As per article 50(2), both tiers of government have legislative and executive powers on matters that fall under their respective jurisdictions. The division of expenditure responsibilities in the Ethiopian federal system, in principle, corresponds with the allocation of legislative powers.

The division of revenue powers among the various tiers of government is one of the pillars of a federal arrangement. Generating revenues for execution of expenditure responsibilities as well as playing a vital role in macroeconomic regulation fall under the manifold functions of taxation powers (Watts, 2008) . Recognized as an indispensable element of a federal system, allocation of revenue powers holds a significant place in the FDRE Constitution. It stipulates the division of taxation powers under different titles; these are the federal and States’ exclusive powers of taxation as well as concurrent and residual (undesignated) areas of taxation (Articles 96-99 of FDRE Constitution).

In addition, the procedures and institutions ensuring vertical or horizontal transfers are the subject matter of the discipline. Also, procedures, institutional setups ensuring subnational borrowings, in particular, and the issue of stabilization and management of economy, in general, are also the subject matters of fiscal federalism.

2.2. Subnational Fiscal Autonomy-Redefined

Whether it is adopted for the economic rationales of efficiency, equity and accountability, or employed as a response to ethno-cultural or political claims of self-determination, decentralization measures should ideally guarantee the financial autonomy of constituent units. It is financial capacity of subnational governments that is a determining factor in the effective implementation of constitutionally mandated expenditure responsibilities and the execution of local policies and priorities.

Significant discrepancy among scholars aside, fiscal autonomy is considered to be the most important measure of subnational financial autonomy. Fiscal autonomy deals with tax autonomy thereby delineating the share of own-source revenue from the total subnational revenue. For this reason, the power to levy taxes (tax autonomy) is the fundamental attribute of fiscal autonomy since it is such power that distinguishes autonomous (own-source) revenues from other types of revenue. Basically, fiscal autonomy is equated with the ability of constituent units to access resources independently, including sub-national discretion over tax bases and tax rates (Blöchliger & Rabesona, 2009) . Moreover, fiscal autonomy allows regional governments to decide the size of their autonomous revenues.

For instance, in the section dealing with division of powers between the federal and regional governments, the FDRE Constitution dictates the general principle for levying and collecting taxes from their respective revenue sources (Art 51/10 and 52/2/e of the FDRE Constitution). Both tiers of the government have the autonomy to administer taxes that fall under their exclusive jurisdiction. Hence, it is possible to say that the Constitution envisaged subnational fiscal autonomy, at least in relative terms.

Therefore, it is necessary to look into the autonomy in generating revenues as well as the volume of such revenues while studying the fiscal autonomy of State governments. Generally speaking, the subnational fiscal autonomy of subnational governments is principally linked with their power and capacity to levy and collect the revenue that is required for meeting their expenditure needs.

3. The Developmental State Vis-à-Vis Fiscal Autonomy of Regions in Ethiopia

Looking at the provisions in the FDRE Constitution dictating powers of taxation, it appears that both levels of government have powers to “levy and collect” taxes in their exclusive jurisdictions, or fiscal (tax) autonomy (Articles 51(10) & 52(2) (e) of the FDRE Constitution). It is known that the notion of tax autonomy is directly related to the power to levy autonomous taxes that is manifested in the autonomy to introduce tax and to set tax bases as well as to set or change tax rates and to introduce tax holidays.

Nonetheless, tax autonomy might be constrained by of federal governments’ regulatory tools including harmonization measures. For instance, centralized institutions and their coercive measures, which are aimed at controlling and directing investment flaws, might be antagonistic towards the revenue autonomy of subnational governments.

Different kinds of actions taken by federal (central) governments, with the view of building an effective DS are among these measures, which can generally be labeled as “moves of recentralization”. The following section addresses some of these “recentralization” measures taken by the federal government of Ethiopia in its move toward “the DS of Ethiopia” as well as its impact on subnational fiscal autonomy.

3.1. Developmentalism, Centralized Mobilization of Investments, and Subnational Autonomy

Striving for the achievement of its ambitious development plan and the realization of an effective DS in Ethiopia generally, the Ethiopian government has initiated extensive reform measures. Among these reforms are wide- ranging measures for revising tax legislation and organizing centralized offices for trade and investment.

Reform measures can be seen in the division of powers with regards to the administration of large-scale agricultural investment lands and comprehensive reforms to investment-incentive legislation both directly related to mobilization of investments. Particularly, these measures were triggered by various factors including the need to promote domestic investment and attract foreign direct investment. Among these wide-ranging and compressive measures taken by the federal government reforms on land administration and investment incentive laws vis-à-vis constitutionally mandated autonomy of regions are discussed below.

3.1.1. Land Reforms

Land administration reforms play a pivotal role in the formation of any DS especially reforms that are directed towards abolishing non-market coercion. Bagchi argues that the extensive pro-peasant reforms of land laws have been the basic features of developmental states since the 16th Century (Bagchi, 2004) . In contrast, the Ethiopian government has not yet adopted a system of private ownership of land.

However, within the existing state ownership of land, extensive reforms have been undertaken by the government. The primary illustration is the practice of centralizing administration of investment land. The Constitution bestows on States the power to administer land and natural resources while legislative power is reserved for the federal government. (Article 51/5 and article 52/2D) of the FDRE Constitution)

Recently, however, the federal government has taken away the power of administration of investment land from regional governments. The law doing so was enacted after the federal government allegedly “induced” regional governments to delegate their power of administering land (Assefa, 2012) . Hence, the Ministry of Agriculture is entrusted with the administration of agricultural investment lands. Besides, a specialized agency, the “Agricultural Investment Land Administration Agency”, has been established to facilitate agricultural investment and land administration (Article 19/1/o of Proclamation No. 691/2010).

Organizing a central office, whose mandates are controlling and directing the mobilization of investments throughout nation is a necessary prerequisite for building an effective DS. Speeches made by higher government officials affirm the central motive behind these recentralization measures which is to make sure “there are no mishaps” through transparent procedures and, by making investors “interact with one entity” (Meles, “The New Broadcast for the World?”, 2010). In this way, the federal government has recentralized rural-land administration to be “developmental”.

The recentralization of land administration, however, is a debatable issue since the notion of “upward delegation” is not recognized under the Ethiopian Constitution. It was intentionally ignored in the making of the Constitution fearing the dangers of centralization, as it is “hinted” at the minutes of the Constitutional Assembly (Assefa, 2012) . Currently the Federal Land Administration Agency is in charge of concluding lease agreements as well as setting land use fees. Yet, the revenue collected by the federal government is transferred to States.

This measure has ultimately limited the relatively unrestrained autonomy of States to set and change tax rates (land use fees)5. As a result, recentralization of the power to administer agricultural investment land has drastically limited tax competition among States. States’ autonomy over agricultural income taxes and land use fees can move them to engage in tax competition. At the same time, relative tax autonomy can also be one way of attracting investments and maximizing revenue.

Recentralizing land administration, and by making itself the “only entity” to deal with investors of large-scale land investments, the federal government may aspire to reduce the prevalence of rent-seeking and corruption. However, if the federal acts are politically motivated then it would amount to discrimination as it ultimately be jeopardizes investment flows and the proportional development of States. Unfortunately, there are cases in which the federal government has allegedly influenced the investment decisions of investors with its power to control nationwide flows of agricultural investments.6

3.1.2. Federal Tax Incentives

In its move towards DS, the Ethiopian government has taken different measures to reinforce its commitment to attracting foreign investment together with encouraging domestic investors. A number of investment and investment incentive proclamations and regulations have been introduced in the two decades old Ethiopian federal system. It would not be far from the truth to argue that there exists no other law that has been amended as frequently as investment incentive regulations.7

One of these measures is the Council of Ministers regulation of investment incentives, which have taken attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and transfer of technology as underlining principles8. As it is appealed by the doctrine of the theory of the DS, the regulation embraced income tax exemptions and exceptions of payments of customs duty.

Unfortunately, one of the consequences of the federal investment incentive laws is the over-extended scope of federal taxation powers. The laws have exacerbated the statutory limitations on the tax/revenue autonomy of States. This is due to the applicability of income tax holidays, stipulated by the federal investment incentive law, not being limited to the areas of taxation that are reserved for the federal government. Rather, the regulation extends its scope of application to the areas that are exclusively reserved for States under the federal covenant.9

The power to levy taxes or tax autonomy bestows States with powers to set and vary tax bases and rates as well as the exclusive power to establish tax holidays. The federal government is now granting “tax holidays” on areas that are exclusively reserved for states. By doing so, the federal government has unconstitutionally constrained the principles of fiscal autonomy of regions in the federal system.

Whatever justifications might be given, the federal government’s statutory limitation on States’ tax autonomy negatively affects the volume of their own-source revenue. At least in the short run, exemptions on dominant tax sources of regional revenue amounts to reductions in their revenue size. Hence, the federal government violated the principle of adverse impact, which imposes a limitation on a tier of the government from exercising its powers of taxation in such a way that adversely affects the powers of the other (Article 100/2 of the FDRE Constitution).

Similar measures were taken and the exact same challenges were posed on subnational governments in other federations, which had once been developmental. For instance, it was only when the 1988 Brazilian Constitution was adopted that the DS-oriented fiscal policy measures of the federal government came in to end in the Brazilian federal system. Induced by subnational governments, the Constitution had abolished the federal government’s power to grant exemptions to state and municipal taxes in Brazil (Mora & Varsano, 2001) .

3.2. Big-Sized Government and Revenue Recentralization in Ethiopia

Many scholars recommend privatizing state-owned public enterprises as a means to address the existing vertical imbalance since it might help to increase the regional tax base (Aalen, 2002) . Thus, it appears to be the commitment of the federal government that matters since privatization creates a limited opportunity for widening the scope of regional revenue sources and capacities without making constitutional amendments. For instance, through privatization the power to levy taxes on incomes of employees of the enterprise, formerly under the federal government’s exclusive area of taxation, would automatically shift to States (Article 97/1 of the FDRE Constitution). Moreover, the process of privatization of public enterprises would enhance the volume of the shared-revenue of regional governments since a company’s profit tax, sales tax and tax on dividends fall under areas of joint taxation.10

Nevertheless, since the time when the DS paradigm was adopted Ethiopia has started to witness a policy shift geared against neoliberalism through “delaying and preventing the introduction of reforms that would reduce the state to the proverbial night watchman” (Meles, 2006) .

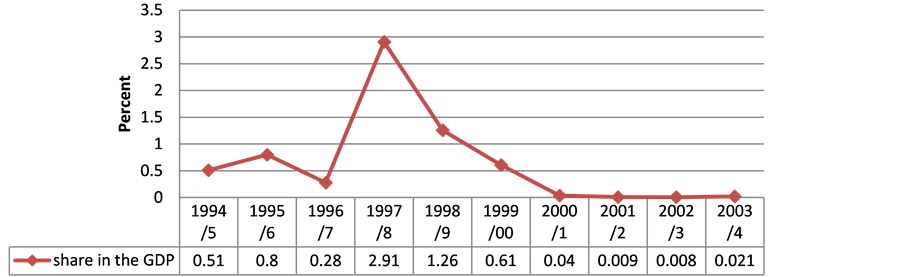

As is depicted in the graph below (Figure 1) since 2001/02 the Ethiopian economy has witnessed its worst performances of privatization. This was lower than other poorly performing countries (Selvam, Meenakshisundararajan, & Iyappan, 2005) . The share of privatization revenues from the country’s GDP fall from a high of 2.91 and 1.26 in 1997/98 and 1998/99 to 0.009 and 0.008 in 2001/02 and 2002/03.

Some of the enterprises that the government is reluctant to privatize are romanticized as “cash cows” because of the huge amount of tax and nontax revenue collected. These enterprises contribute significantly to the existing financial centralization in the Ethiopian federal arrangement in various ways.

First, since these enterprises are owned by the federal government, the latter has been able to collect the lion share of the total non-tax revenue of the country. At the same time, these enterprises are significant sources of federal taxes since the Constitution assigns both levels of government to levy and collect (most of) the taxes in their respective enterprises11. For this reason, state governments barely benefit from public enterprises in the con- temporary arrangement. Regional governments enjoy almost nothing in the form of proceeds (tax or nontax revenue) form public enterprises.

Figure 1. Privatization proceeds as percentage share of the GDP. Sources: The Ethiopian Privatization Agency (2004) and World Bank (2004) .

Other federal systems have possessed, or still possess, huge public enterprises in their attempts to realize eco- nomic growth through policies of developmentalism. What makes the Ethiopian case different is the impact of these enterprises on the degree of fiscal imbalance or financial recentralization. Unlike the Ethiopian federal system, public enterprises are recognized for their productive contributions to subnational finance. For instance, state governments were allowed to own public enterprises in the Brazilian federal system. Due to this, the proceeds of these enterprises contributed significantly to the financing of subnational expenditure needs in the late 1970s (Mora & Varsano, 2001) .

Generally, big-sized governments or the DS paradigm in general, are usually perceived as anti-decentraliza- tion measures since economic decentralization (privatization) is included under its broader interpretation. To put it differently, “state activism” in a DS contradicts with the neoliberal perception of decentralization that juxtaposes decentralization with small-sized governments. For the effective realization of the DS, the Ethiopian government prefers to be “big” and is now spending massive amounts of finance on the expansion of existing enterprises and the establishment of new state-owned chemical and engineering companies.12

3.3. Trends of Vertical Imbalance in the DS of Ethiopia

A move toward the DS of Ethiopia, particularly since 2006, can be seen as a counter measure to the earlier promises of decentralization in the polity. This could be one of the manifestations of the Ethiopian government’s encounter with the neoliberal advocates. Big-sized government in contemporary Ethiopia refutes neoliberal’s perception of decentralization, while its resistance to economic liberalization is, in general, a move against neoliberalism.

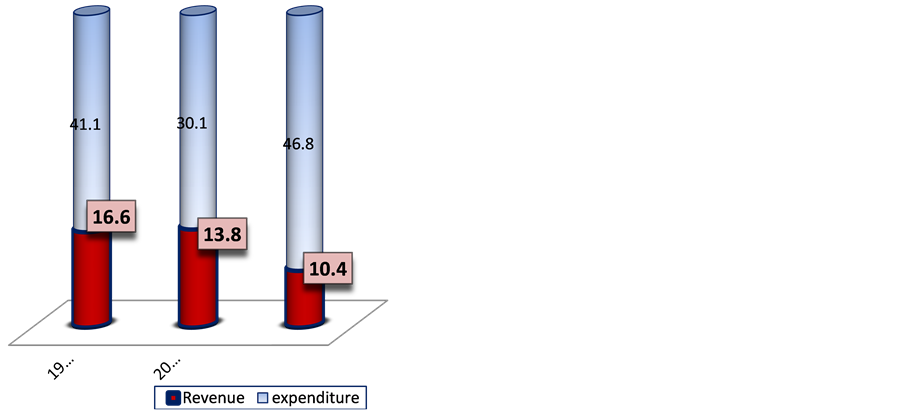

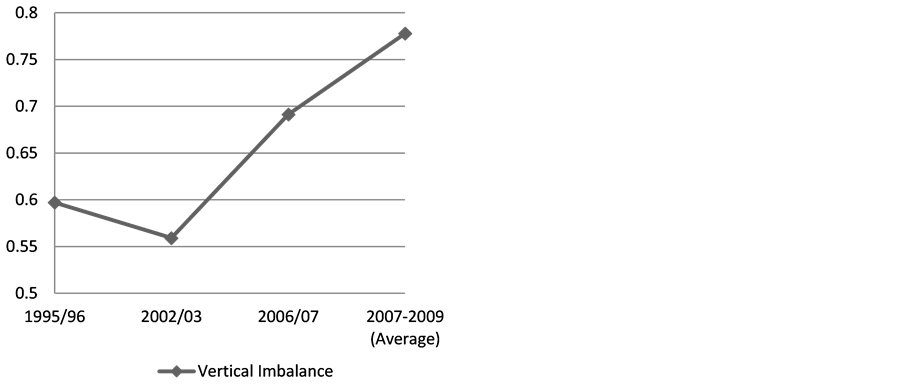

By the same token, States’ share in the aggregate national revenue has drastically decreased since 2001 while their shares of total expenditure remain constant (Figure 2). This trend reflects the ever-increasing vertical fiscal imbalance in the federal system especially since 2006. Though vertical imbalance has always been an issue to worry about in the federation, the degree to which it has grown overtime is even more worrisome.13

The post-2001 recentralization measures of the federal government have exacerbated the problem of fiscal imbalance. As it has been stated previously, some of the federal governments’ measures have significantly limited subnational tax autonomy thereby reducing the States’ aggregate revenue volume. On the other hand, the

Figure 2. Trends of aggregate regional revenue and expenditure as a percentage of the total national revenue and expenditure. Source: Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, World Bank (2004) .

growth of government-owned public enterprises has significantly contributed to the federal government being both tax and non-tax revenue sources.

Therefore, fiscal measures that are motivated by the DS theory have multifaceted implications on the degree of financial recentralization. These measures not only extend the powers of the federal government, but also constrain subnational revenue autonomy making the degree of vertical imbalance in the federal system quite high.

4. Conclusion

It is fair to say that the adoption of the DS paradigm overlooks the fiscal autonomy as well as the revenue volumes of regional states. The recent act of “upward delegation” of the power to administer land is allegedly an unconstitutional act by taking away the power to levy the taxes from the States. Similarly, due to the fact that the scope of applicability of federal tax incentive legislation has been extended to the exclusive jurisdictions of regions, the federal government exempts investors from regional taxes. Justified by the development paradigm, such measures have undermined the constitutionally dictated revenue autonomy of regions in addition to affecting the volume of own-source revenues.

The over-centralized allocation of revenue sources, together with weak tax administration at the regional level, is blamed for the existing fiscal imbalance in the Ethiopian federal system. On the other hand, economic liberalization has been proposed as one of the means that could improve regional revenue without a need for a constitutional amendment. Nevertheless, the analysis shows that the government is unlikely to liberalize the economy in the near future mainly because of the developmental ideology it has adopted.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Solomon Nigussie, Assistant Professor of Law, Ethiopian Civil Service University and Diana Van Bogaert, Director of Legal English Unit, America University in Cairo for their constructive comments. I also wish to acknowledge the two anonymous reviewers for their important remarks. I am solely responsible for any errors of fact or interpretation.

Cite this paper

ZemenuYesigat,11,11, (2016) Subnational Fiscal Autonomy in a Developmental State: The Case of Ethiopia. Beijing Law Review,07,42-50. doi: 10.4236/blr.2016.71005

References

- 1. Aalen, L. (2002). Ethnic Federalism in a Dominant Party State: The Ethiopian Experience 1991-2000. Bergen: Michelson Institute Development Studies and Human Rights, 2(02).

- 2. Abbink, J. (2011). Ethnic-Based Federalism and Ethnicity in Ethiopia: Reassessing the Experiment after 20 Years. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5, 596-618.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2011.642516 - 3. Assefa, F. (2007). Federalism and Accommodation of Diversity in Ethiopia: A Comparative Study (revised edition). Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers.

- 4. Assefa, F. (2012). Ethiopia’s Experiment in Accommodating Diversity: 20 Years’ Balance Sheet. Regional & Federal Studies, 22, 435-473.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2012.709502 - 5. Bagchi, A. K. (2000). The Past and the Future of the Developmental State. Journal of World-Systems Research, 6, 398-442.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2000.216 - 6. Bagchi, A. K. (2004). The Developmental State in History and in the Twentieth Century. New Delhi: Regency Publications.

- 7. Blochliger, H., & Rabesona, J. (2009). The Fiscal Autonomy of Sub-Central Governments: An Update. OECD Network on Fiscal Relations across Levels of Government, No. 9, Paris: OECD.

- 8. Castanhar, J. C. (2003). Fiscal Federalism in Brazil: Historical Trends Present Controversies and Future Challenges. P. 4VIII Congreso Internacional del CLAD sobre la Reforma del Estado y de la Administración Pública, Panamá, 28-31 October 2003.

- 9. Council of Ministers (1998). Investment Incentives Council of Ministers (Amendment) Regulation (Regulation No.36/1998).

- 10. Doner, F., et al. (2005). Systemic Vulnerability and the Origins of Developmental States: Northeast and Southeast Asia in Comparative Perspective. International Organization, 59, 327-361.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0020818305050113 - 11. Eshetu, C. (1994). Issues of Vertical Imbalance in Ethiopia’s Emerging System of Fiscal Decentralization. In E. Chole (Ed.), Fiscal Decentralization in Ethiopia (pp. 167-191). San Francisco, CA: AAU Press.

- 12. Fasil,, N. (1997). Constitution for Nation of Nations: The Ethiopian Prospect. Trenton, NJ: The Red Sea Press.

- 13. Investment (Amendment) Proclamation No. 373/ 2003.

- 14. Investment Incentives (Amendment) Council of Ministers Regulations (Regulations No. 9/1996).

- 15. Investment Incentives and Investment Areas Reserved for Domestic Investors, (Regulations No. 84/2003).

- 16. Investment Incentives Council of Ministers Regulations (Regulation No.7/1996).

- 17. Investment Proclamation No. 280/ 2002.

- 18. Investment Proclamation No. 769/2012.

- 19. Johnson, C. (1982). MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- 20. Keller, E. J. (2002). Ethnic Federalism, Fiscal Reform, Development and Democracy in Ethiopia. African Journal of Political Science, 7, 21-50.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajps.v7i1.27323 - 21. Meles, Z. (2006). Speech on the Africa Task Force, Brooks World Poverty Institute, Manchester University, UK 3-4 August 2006.

http://ethioembassy.org.uk/Archive/Prime%20Minister%20Meles%20Afica%20Task%20Force%20speech.htm - 22. Messay, K. (2011). Meles Zenawi’s Political Dilemma and the Developmental State: Dead-Ends and Exit.

http://ecadforum.com/2011/06/13/meles-zenawis-political-delemma-and-the-developmental-state-dead-ends-and-exit/ - 23. Mora, M., & Varsano, R. (2001). Fiscal Decentralization and Subnational Fiscal Autonomy in Brazil: Some Facts of the Nineties. Instituto De Pesquisa Economica Aplicada, Texto Para Discussao No.854.

- 24. Proclamation to Provide for the Establishment of National/Regional Self-Governments, Negarit Gazette (Proclamation No. 7/1992).

- 25. Prud'homme, R., & Shah, A. (2002). Centralization v. Decentralization: The Devil Is in the Details. Paper presented for a Conference held in Porto Alegre, World Bank.

www.ibrarian.net/navon/paper/Centralization_v_Decentralization__The_Devil_IS.pdf?paperid=5966826 - 26. Rao, G. (2006). Fiscal Federalism in Planned Economies. In E. Ahmad, & G. Brosio (Eds.), Handbook of Fiscal Federalism (pp. 224-239). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781847201515.00017 - 27. Regulation to Amend the Investment Incentives and Investment Areas Reserved for Domestic Investors (Regulation No. 146/2008).

- 28. Regulations on Investment Incentives and Investment Areas Reserved for Domestic Investors (Regulation No. 84/2003).

- 29. Selvam, J., Meenakshisundararajan, A., & Iyappan, T. (2005). Privatization and Capital Accumulation: Empirical Evidences from Ethiopia. AJEP, 12.

- 30. Solomon, N. (2008). Fiscal Federalism in the Ethiopia Ethnic-Based Federal System (2nd ed.). Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers.

- 31. Thakur, R. (1995). The Government and Politics of India. London: Macmillan Press Ltd.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24100-2 - 32. The Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Proclamation No. 1, 1995.

- 33. The Ethiopian Privatization Agency (2004). Privatization Proceeds from 1994/95-2002/03. Addis Ababa: Department of Finance and Administration Department.

- 34. The FDRE Growth and Transformation Plan (2010/11-2014/15), Volume I: Main Text, (Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Nov. 2010).

- 35. Transitional Period Charter, Negarit Gazette, No 1/ 1991.

- 36. Watts, R. (2007). Decentralization and Recentralization: Recent Developments in Russian Fiscal Federalism. Working Paper (2), Institute of Intergovernmental Relations.

- 37. Watts, R. (2008). Comparing Federal Systems (3rd ed.). Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- 38. World Bank (2004). Ethiopia: Public Expenditure Review—The Emerging Challenge, Report No.29338-ET.

NOTES

1Some scholars prefer to use terms like “multi-cultural” or “multi-ethic” federalism to refer the existing federal arrangement in Ethiopia.

2 Transitional Period Charter, Negarit Gazette, No 1/1991 ; Proclamation to provide for the Establishment of National/Regional Self-Gov- ernments, Negarit Gazette, Proclamation No. 7/1992 .

3 The Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Proclamation No. 1, 1995 ; (hereinafter refereed as the FDRE Constitution)

4Though Ethiopia’s adoption of the new developmental paradigm was publically declared in 2006, the ruling elites claimed that it was adopted around 2001, immediately after the ruling party’s split. For a better discussion on this issue see, Meles (2006) .

5Some scholars do not consider such kinds of revenues as own-source revenues. See, Watts (2007) .

6There are a number of reports on federal government’s direct involvement in decisions of investors including where to invest. For instance an investor who asked for an agricultural land in Benishangul-Gumuz Region was “taken around” by the federal government “to look at different land areas” (Horne, 2011) .

7For instance, Proclamation No. 280/ 2002 , (Investment Proclamation); Proclamation No. 373/ 2003 , (Investment (Amendment) Proclamation), and Proclamation 769/2012 , (Investment Proclamation) could be mentioned among the proclamations. As long as Regulations are concerned, the following are issued by the Council of Ministers with regard to investment incentives; Regulation No.7/1996 (Investment Incentives Council of Ministers Regulations); Council of Ministers Regulations No. 9/1996 (Investment Incentives (Amendment) Council of Ministers Regulations); Council of Ministers Regulations No.36/1998 (Investment Incentives Council of Ministers (Amendment) Regulation); Council of Ministers Regulations No. 84/2003 , (Council of Ministers Regulations on Investment incentives and Investment Areas Reserved for Domestic Investors ); Regulation No. 146/2008 , (Council of Ministers Regulation to Amend the Investment Incentives and Investment Areas Reserved for Domestic Investors Regulation)

8Investment Incentives and Investment Areas Reserved for Domestic Investors, Council of Ministers Regulations No. 84/2003 .

9For instance, there is 2 - 7 years’ exemption from agricultural income tax (which is exclusive jurisdiction of states) if the investor exports 50 percent of his/her product or supplies 75 percent of his/her product as production input to an exporter. (Council of Ministers Regulations No. 84/2003)

10Though Sales tax is not mentioned in the English version, the Amharic version, which prevails in cases of inconsistencies, included it. See, article 98/2 cum article 106. Excise tax is omitted in both versions despite its existence in practices, which ‘seems to be a slip of pen’. See, Solomon (2008) .

11Except income from remainders of employees which is the state power (Articles 96(3) & 97(7) of the FDRE Constitution).

12See, The FDRE Growth and Transformation Plan (2010/11-2014/15) , Volume I: Main Text, (Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Nov. 2010).

13The vertical Imbalance index measures the percentage shares’ of the aggregate revenue and expenditure of States from that of the national total. It is computed as; Vertical Imbalance (VI) = 1 − [(SR/TR)/(SE/TE)] where SR is aggregate revenue of States and TR is the national total revenue. Similarly, SE indicates the combined regional expenditure while TR is the total expenditure of the nation. Scholars agree that, in normal situations, the index should not be greater than 0.5. See, Eshetu Chole (1994) .