Open Journal of Medical Psychology

Vol.2 No.4(2013), Article ID:38379,2 pages DOI:10.4236/ojmp.2013.24025

Strength, But Not Direction, of Handedness Is Related to Height

1Psychology Department, Montclair State University, Montclair, USA

2Department of Psychology, Tufts University, Medford, USA

3US Army NSRDEC, Cognitive Science, Natick, USA

Email: *propperr@mail.montclair.edu

Copyright © 2013 Ruth E. Propper et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received July 3, 2013; revised August 3, 2013; accepted August 10, 2013

Keywords: Handedness; Stature; Prenatal Testosterone

ABSTRACT

Left-handers are reputed to be shorter than right-handers. However, previous research has confounded handedness direction (leftversus right-handedness) with handedness strength (consistency with which one hand is chosen across a variety of tasks; consistentversus inconsistent-handedness). Here, we support a relationship between handedness strength, but not direction, and stature, with increasing inconsistent-handedness associated with increasing self-reported height.

1. Introduction

Left-handers are reputed to be shorter than right-handers [1-4]. However, previous work has assessed handedness via archival records of sports figures, using one activity (e.g. batting) to classify handedness, thereby confounding handedness direction (leftversus right-handedness) with handedness strength (consistency with which one hand is chosen across a variety of tasks; consistentversus inconsistent-handedness). Handedness direction and strength both contribute to between-subject variation in cognitive/physiological measures [5], and are likely to contribute to individual differences in handedness effects on stature as well, presumably via prenatal androgen exposure variation. In the only study [6] directly querying participants’ handedness, increasing consistent-left and consistent-right-handedness were both associated with decreased height. However, in that study, handedness was dichotomized, which does not allow for assessment of overall direction versus strength of handedness and height relationships. Furthermore, it is unclear how

height was assessed. Here, in this Short Report, we support a relationship between handedness strength, but not direction, and stature.

2. Methods

As part of a larger protocol, participants (N = 141) completed written consent (the study was approved via the MSU Institutional Review Board and the Army Human Research Protection Office), self-reported their height, and filled out the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI). The EHI consists of 10 activities that participants rate as performing with the right or left hand “always”, “usually”, or having no hand preference. Graduated scoring results in a range from −100 (perfectly consistent-lefthandedness) to +100 (perfectly consistent-right-handedness).

3. Results

Handedness Direction: Unpaired t-test comparing height (cm) between left- (n = 12; EHI score equal/below 0) and right- (n = 129; EHI score above 0) handers was nonsignificant (p > 0.20). Height also did not correlate with EHI overall or as a function of gender (p > 0.30). See Figure 1(a).

Handedness Strength: Height negatively correlated with absolute value of EHI (|EHI|), r(139) = −0.22, p < 0.01, a measure that collapses across handedness direction, while maintaining handedness strength. See Figure 1(b). This effect was evident in men (n = 35, r = −0.41, p = 0.01), but not women (n = 106; p > 0.90).

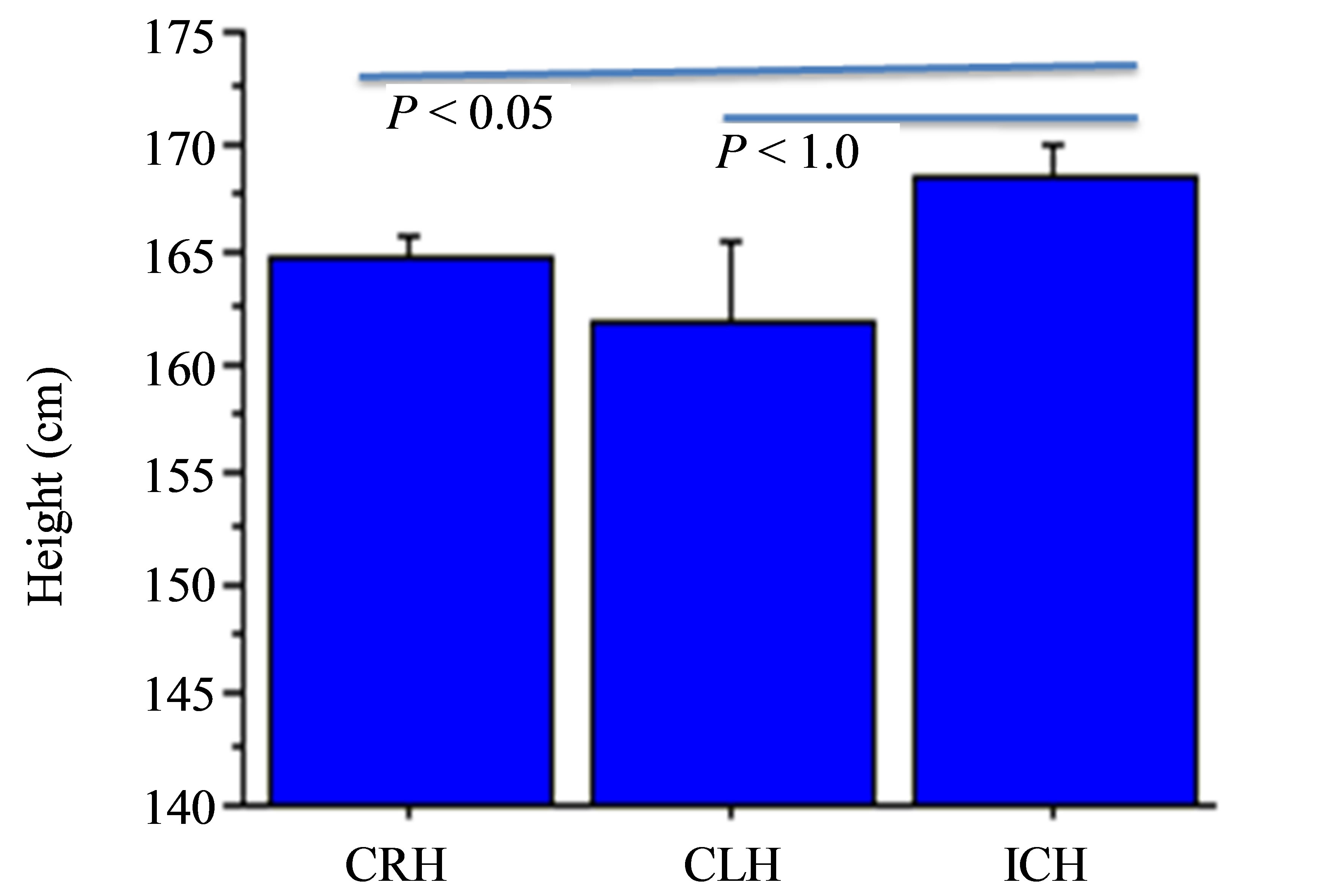

Handedness Direction and Strength: Handedness was trichotomized into consistent-left-(CLH), right-(CRH), and inconsistent-handed (ICH) groups via the median of the |EHI| score (|80|) [see 5]. Scores +80 and above were CRH (n = 71), scores −80 and below were CLH (n = 7), and scores +75 to −75 were ICH (n = 63); A one-way Analysis of Variance revealed an effect (f(2,138) = 3.0, p = 0.05); ICH (x = 168.41, sd = 11.47) were taller (by 3.72 cm) than CRH (x = 164.69, sd = 8.66; Fisher’s PLSD, p < 0.05), and marginally (Fisher’s PLSD p = 0.10) taller (by 6.58 cm) than CLH (x = 161.83, sd = 9.92). See Figure 2.

4. Discussion

Handedness strength (measured via the absolute value of

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 1. (a) Height is not correlated with direction of handedness (EHI), p > 0.20. (b) Height is negatively correlated with strength of handedness (|EHI|), p < 0.01.

Figure 2. Height as a function of handedness group.

shared mediation by in utero hormonal factors (e.g. testosterone), a suggestion supported by the fact that men, not women, demonstrated this relationship. Leftand right-handers did not differ from each other, nor did consistent-rightand consistent-left-handers. Inconsistenthanders however were taller than both consistentlyhanded groups, and significantly so relative to consistentright-handers. Limitations of the present finding are based primarily on the limited number of participants, the need for additional testing of men and women, and the reliance on self-reported height. Nevertheless, the results call into question previously analyzed archival data based on single measures of handedness. The results here further support that non-right-handedness is not a homogenous trait that can be determined by performance on one activity [5]. Given that inconsistent-handers are taller than both consistent-leftand consistent-right-handers, data sets that incorporate strength of hand preference may more accurately characterize the relationship between height and hand preference.

REFERENCES

- E. L. Abel and M. L. Kruger, “Lefties Are Still a Little Shorter,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, Vol. 104, No. 2, 2007, pp. 405-406. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pms.104.2.405-406

- S. Coren, “Southpaws—Somewhat Scrawnier,” American Medical Association, Vol. 262, No. 19, 1989, pp. 2682- 2683.

- R. Fudin, L. Renninger and J. Hirshon, “Analysis of Data from Reichler’s (1979) the Baseball Encyclopedia: RightHanded Pitchers are Taller and Heavier than Left-Handed Pitchers,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, Vol. 78, No. 3, 1994, pp. 1043-1048. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pms.1994.78.3.1043

- R. Pollard, “A Difference in Heights and Weights between Right-Handed and Left-Handed Bowlers at Cricket,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, Vol. 81, No. 2, 1995, pp. 601-602. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pms.1995.81.2.601

- E. Prichard, R. E. Propper and S. D. Christman, “Degree of Handedness, But Not Direction, Is a Systematic Predictor of Cognitive Performance,” Frontiers in Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 4, 2013, pp. 1-6.

- U. Tan, “The Relation of Body Height to Handedness in Male and Female Rightand Left-Handed Human Subjects,” International Journal of Neuroscience, Vol. 63, No. 3-4, 1992, pp. 217-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pms.1995.81.2.601

NOTES

*Corresponding author.