Open Journal of Preventive Medicine

Vol. 2 No. 4 (2012) , Article ID: 24993 , 5 pages DOI:10.4236/ojpm.2012.24064

Division of labor, perceived labor-related stress and well-being among European couples

![]()

Department of Health Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Östersund, Sweden; *Corresponding Author: Emma.Hagqvist@miun.se

Received 14 August 2012; revised 21 September 2012; accepted 29 October 2012

Keywords: Division of Labor; Labor Involvement; Perceived Labor-Related Stress; Well-Being

ABSTRACT

Background: The objective of this study was to analyze how involvement in paid and unpaid work and perceived labor-related stress are related to the well-being of married or cohabiting men and women in Europe. Methods: Data from the European Social Survey round two has been used. The sample consists of 5800 women and 6952 men, aged between 18 - 65 years. Exposure variables were divided into labor involvement, time spent on paid and unpaid work, and labor-related stress. Multiple logistic regressions with 95% confidence interval were used. Results: Women spent more hours on housework than men did, but fewer hours on paid work. Women tended to perceive higher degrees of housework-related stress than men did. Furthermore, women who experienced houseworkrelated stress tended to have higher odds of reporting a low level of perceived well-being than men, while men had higher odds of reporting a low level of perceived well-being when they experienced work/family conflicts. Conclusion: For both men and women, the perceptions of labor involvement are of more importance for the well-being than the actual time spent on paid and unpaid work. This implies that, when studying the relationship between labor involvement and well-being, perceived stress should be considered.

1. INTRODUCTION

Traditional views of the gendered division of labor imply that women take responsibility for the home and family, while men are the breadwinners [1]. These views are reflected in statistics showing that the distribution of paid and unpaid work is most often unequally divided between married or cohabiting men and women. Recent studies show that American and European women spend less time performing paid work and more time performing unpaid work than men do [2-7]. However, the equalization of responsibilities and opportunities between married or cohabiting men and women regarding the division of work is a common political goal in the European Union. These goals are based on the belief that an equal distribution of labor will equalize power relations within couples and promote the well-being of both women and men [8].

Several studies have explored the relationship between time spent on paid or unpaid work and well-being. Time spent on paid work seems to increase well-being for both women and men [7,9], but the relationship is curvilinear, and working too many hours can have the opposite effect on well-being [10]. In contrast, for both men and women, time spent on unpaid work seems to lower well-being or has no effect on it [7,9,11]. Some studies in the US and in Europe have found that time spent on housework contributes to gender differences in well-being. The generally lower sense of well-being among women than among men is associated with men’s lower, and women’s higher, contribution to housework [2,4,7,12]. However, some studies have not found any significant relationship between the distribution of work within couples and the level of well-being [13,14], and some studies have even highlighted the fact that the situation is more stressful when spouses share the household work than if it is divided according to traditional patterns [15].

In addition to the influence of the actual involvement in paid and unpaid work on women’s and men’s wellbeing, there are also studies that have highlighted the importance of perceptions related to the actual level of involvement in labor. One is the perceived level of work/ family conflicts (WFCs). Men and women with a high level of involvement in paid work followed by a high engagement in unpaid work might have difficulties combining these two domains, which, in turn, can lead to an increased risk for experiencing WFC. Previous studies have reported that WFCs are more numerous for women than for men [14,16]. Irrespective of gender, WFCs have been shown to have a strong association with health problems [14], more so for women than for men [17]. High demands from work and family also tend to increase the risk of illness and absenteeism from work, with no significant difference between men and women [18].

Furthermore, some studies have shown that the perception of responsibility for housework and childcare is of more importance for psychological distress than the actual time spent on those activities [4,9,19]. Some researchers have analyzed perceptions related to how spouses divide labor, i.e., perceptions of fairness in the division of work(20, 21) or perceptions of the amount of hours spent on housework [4,20,21], but none of these studies has related such perceptions to the level of well-being.

Thus, there are studies on the relationship between actual labor involvement among women and men and indicators of health, and there are studies on the importance of perceptions related to the level of labor involvement and health outcomes. Although there are studies on labor involvement, perceptions and well-being, there are still gaps in our knowledge of the relationships between them. Studies of the relevance of involvement in paid and unpaid work have reported contradictory results. Furthermore, there are still relatively few studies that have analyzed the importance of perceptions related to involvement in labor, and there are even fewer studies that have compared the influence of actual involvement with the influence of perceptions of the involvement in the same study. Perceptions that have been studied (perceived WFC, responsibility or fairness) are in one way or another related to the degree to which the individual perceives the level of labor involvement as stressful. Therefore, this article focuses on the influence of perceived labor-related stress (including measures of stress related to paid work and housework, perceived WFCs and the level of disagreement about the division of labor) in relation to the influence of actual involvement in labor on well-being.

Aim

The aim of this study was to investigate how involvement in paid and unpaid work and perceived labor-related stress are related to the well-being of cohabiting men and women in Europe.

- Does actual labor involvement affect reported wellbeing?

- Is perceived labor-related stress related to reported well-being?

- Does actual labor involvement or perceived laborrelated stress have a stronger relationship to reported well-being?

- For the above questions, are there any differences between men and women?

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

The data originate from the European Social Survey (ESS) round two, which was conducted in European countries from 2004 to 2005. A newer version of the ESS questionnaire with the same round of questions exists, but the questions have been changed in such a manner that they cannot be used for this article. Within the ESS, respondents were selected using a random probability method for each country [22]. The ESS sample is weighted for the country population and sample method.

The sample selected for this study was aged between 18 - 65 years. They were married or cohabiting and were employed full or part time. The sample consisted of 12,752 respondents, 5800 women (45.5%) and 6952 men (54.5%). The mean age was 41.8 years for women and 43.5 years for men. Unanswered questions included in this study were coded as missing.

2.2. Data Collection and Variables

The data were collected using face-to-face interviews with questionnaires that were similar in each country with the exception of some country-specific questions, such as questions about education. The questionnaire was translated into each respective language. Further information on the data collection can be found elsewhere [22].

2.2.1. Outcome Variable

Well-being was measured using the WHO-five wellbeing index [23]. The respondents were asked to respond on a six-point Likert scale (0 - 5) as to whether they, during the last two weeks, had felt cheerful and in good spirits, calm and relaxed, active and vigorous, had woken up feeling fresh and rested and felt that life had been filled with interesting things. The scores were added to an index reaching from 0 - 25, where a higher score represents better well-being (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82). The index was dichotomized with the first quartile as the cut-off point: 0 - 13 = 1 and 14 - 25 = 0.

2.2.2. Exposure Variables

The exposure variables are divided into two main categories: actual labor involvement and perceived laborrelated stress.

1) Labor Involvement Labor involvement comprised four variables: work hours, time spent on housework, share of housework and total labor time. Work hours were measured as the total number of hours spent on paid work, including overtime, per week. The hours of labor were limited to 100 hours per week—those exceeding 100 hours were treated as an internal bias and were excluded from the analysis. Housework was defined as tasks performed around the home, such as cooking, washing, cleaning, care of clothes, shopping and maintenance of property. In the ESS, there is no direct question regarding time spent on housework, so the variable was calculated according to the method of Boye [2,24]. Share of housework was divided into four groups: 0 = up to 1/4 of the time, 1 = from 1/4 to 1/2 of the time; 2 = from 1/2 to 3/4 of the time; and 3 = from 3/4 to all of the time. Total labor time was calculated by summing the time spent on housework and work hours. This variable was divided into three categories: 1 = 0 - 45, 2 = 46 - 55 and 3 = over 55 hours.

2) Perceived Labor-Related Stress Four variables describe labor-related stress. Work-related stress was measured by one question regarding the respondent’s feeling of having enough time to do work assignments. Housework-related stress was an index of 0 - 12 points, with null representing no stress. The index was comprised from three questions in the ESS questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.49). Using a five-point scale, the respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed that they had enough time to get everything done at home, that their housework was monotonous and that housework felt stressful.

The third variable, the perceived conflict between work and family (WFC), was a computed index (0 - 12 points) based on three questions with answers on a fivepoint scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.66). The questions concerned how often the respondent worried about work problems when not at work, felt too tired after work to enjoy the things he or she would have liked to do at home and felt that the job prevented him/her from giving the time he/she wanted to the partner or family. The above three variables were divided into four quartiles: 1) no stress; 2) low stress; 3) moderate stress; and 4) high stress.

The fourth variable consisted of two questions about the level of disagreement between the spouses about the division of housework and time spent on paid work. The index (0 - 12 points) was dichotomized into no disagreement or disagreement less than once a month (0 = agree, 1 - 2 points) and disagreement ranging from once a month to every day (1 = disagree, 3 - 12 points). A relatively high level of disagreement indicated that the division of labor was perceived as stressful.

2.2.3. Control Variables

The exposure variables were controlled for the following background variables: education, number of children, age, and gender attitudes. School systems differ between countries, so the variable education was based on the total number of years of education. This variable was divided into three groups: 1 = 0 to 9 years of education, 2 = 10 to 13 years and 3 = more than 13 years of education. Children were dichotomized into two categories: 0 = no children in the household and 1 = children living in the household. Age was divided into three categories: 18 to 33 years, 34 to 48 years and 49 to 65 years.

Gender attitude was added as a control variable because it is often a factor of importance when studying the division of labor between spouses [2,25-27]. The index gender attitude was composed of three responses. The respondents rated on a 5-point scale (0 - 4), ranging from agree strongly to disagree strongly, whether they agreed with the following statements: “a woman should be prepared to cut down on her paid work for the sake of her family”, “men should take as much responsibility as women for home and family”, and “men should have more right to a job than women”. The index (0 - 12) was coded so that a low value indicated a traditional gender attitude and a high value indicated a belief in gender equality. The index was dichotomized into 0 = traditional gender attitudes (1 - 6) and 1 = gender-equal attitudes (7 - 12).

2.3. Ethical Consideration

The ESS ethical frameworks for data collection follow the Declaration on Ethics of the International Statistical Institute [28]. All respondents gave written approval before entering the study and had the ability to stop the interview at any time.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Initially, descriptive statistics of the outcome and exposure variables were calculated for the total sample as well as for women and men separately. The descriptive statistics presented consist of the mean values (with standard deviations) for the continuous variables and distributions for the categorical variables. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used to show the differences in the mean scores between men and women using the independent T-test.

A multiple logistic regression was carried out using odds ratios (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). First, the crude data of all exposure variables were tested. Secondly, two models were developed. In the first model, the variables representing involvement in work were tested, and in the second model, labor-related stress variables were added. The results are presented in two tables, one for men and one for women. The Statistical Package of Social Science version 19 was used to analyze the data.

3. RESULT

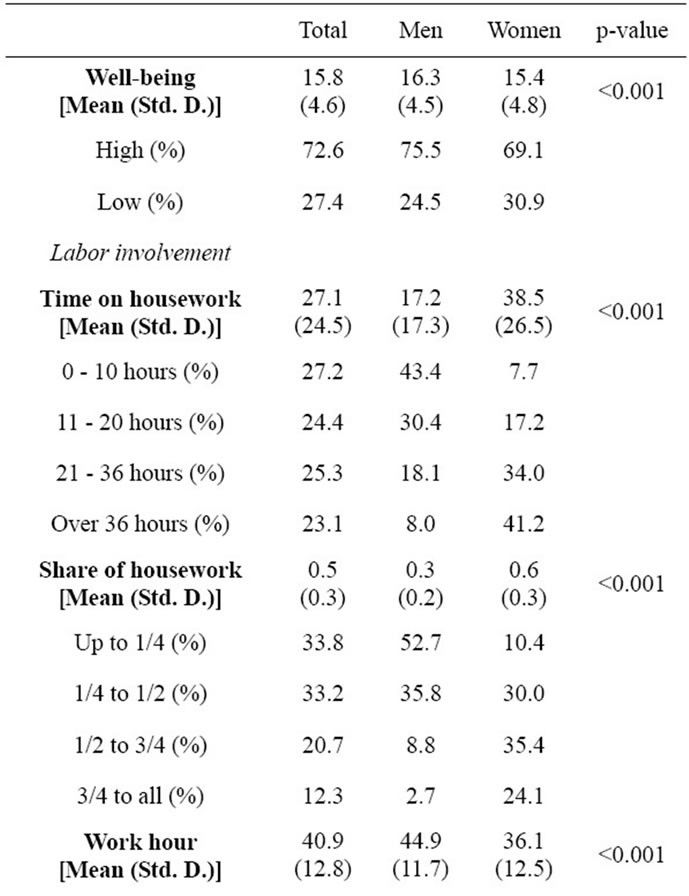

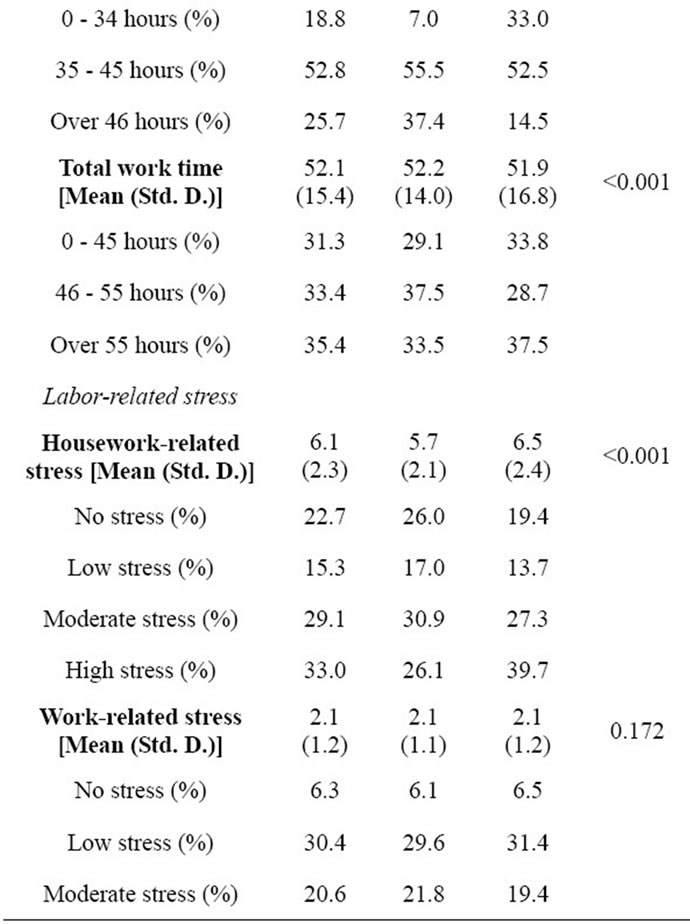

Table 1 provides a descriptive overview of the outcome and exposure variables for cohabiting or married

Table 1. Distribution and mean values with standard deviations for variables measuring well-being, involvement in work, perception of division of work for cohabiting or married women and men, p-value for difference of mean between men and women.

men and women in Europe.

The results show that women reported somewhat lower levels of well-being than men did.

In addition, Table 1 shows that cohabiting or married men and women spent about the same number of hours on labor each week, but men spent on average fewer hours on housework and more hours on paid work than women did. Most men reported spending up to 10 hours each week on housework while the majority of women spent over 36 hours. Meanwhile, the mean work hours each week were 44.9 hours for men and 36.1 hours for women. Furthermore, women experienced higher mean levels of stress from housework than men did. Both men and women experienced work-related stress, WFCs and disagreement about how to divide labor.

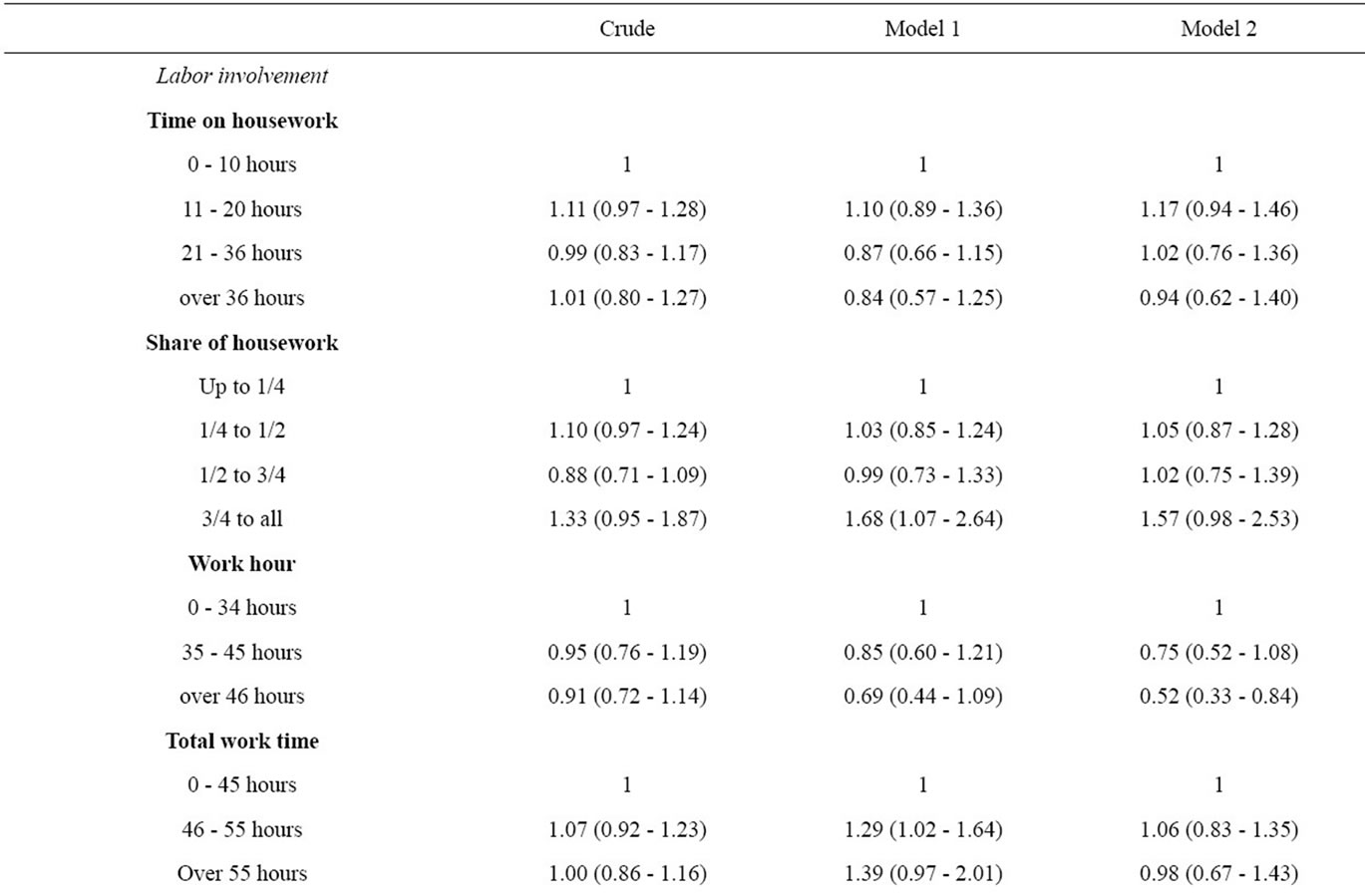

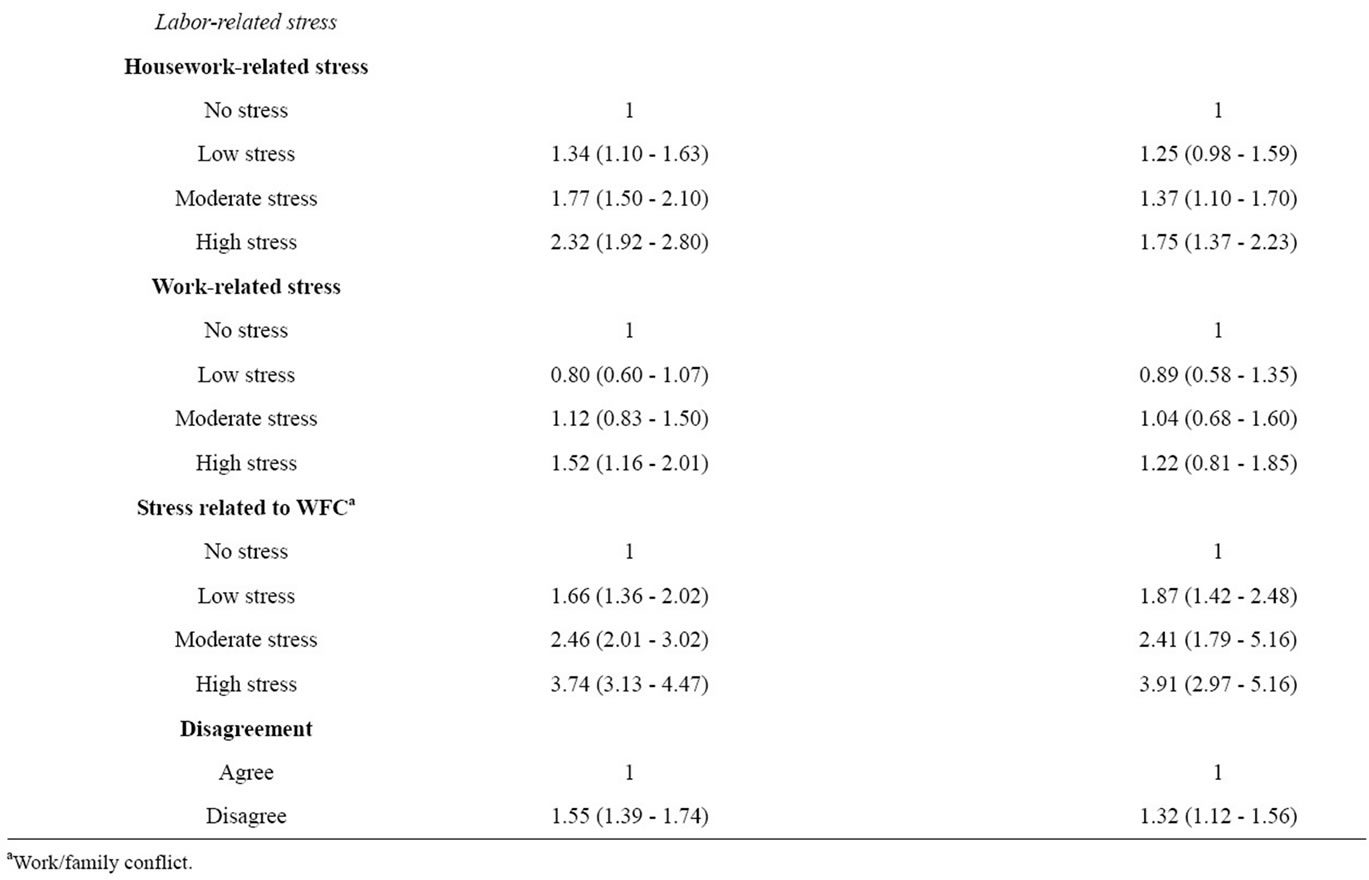

All the models in Tables 2 and 3 were controlled for the following variables: age, number of children, education and gender equality (data not shown). Table 2 provides the ORs (95% CI) for reported well-being among cohabiting or married employed men in Europe. In Table 2, the crude ORs show no significant relationship between men’s labor involvement and well-being. All variables measuring perceived labor-related stress were significantly related to a low level of perceived wellbeing.

In Table 2, Model 1, the results of a multivariate test of all variables measuring labor involvement among men are presented. In contrast to the crude data, significant relationships were found between a low level of perceived well-being and both doing more than three quarters of the housework and total working time between 46 - 55 hours. When controlling for labor-related stress in Model 2 (Table 2), the significant relationships from Model 1 disappeared. Instead, Model 2 shows that men who report moderate or high stress related to housework and disagreement had increased odds of reporting a low level of well-being. Furthermore, men who reported stress

Table 2. Multiple logistic regression models showing the OR with 95 % CI for low well-being among employed men living with a wife or a partner.

Table 3. Multiple logistic regression models showing the OR with 95 % CI for low well-being among employed women living with a husband or a partner.

related to WFCs were four times as likely to report a low level of perceived well-being than men who reported no conflicts. However, there was no relationship between men’s perception of work-related stress and well-being, which differs from the crude data.

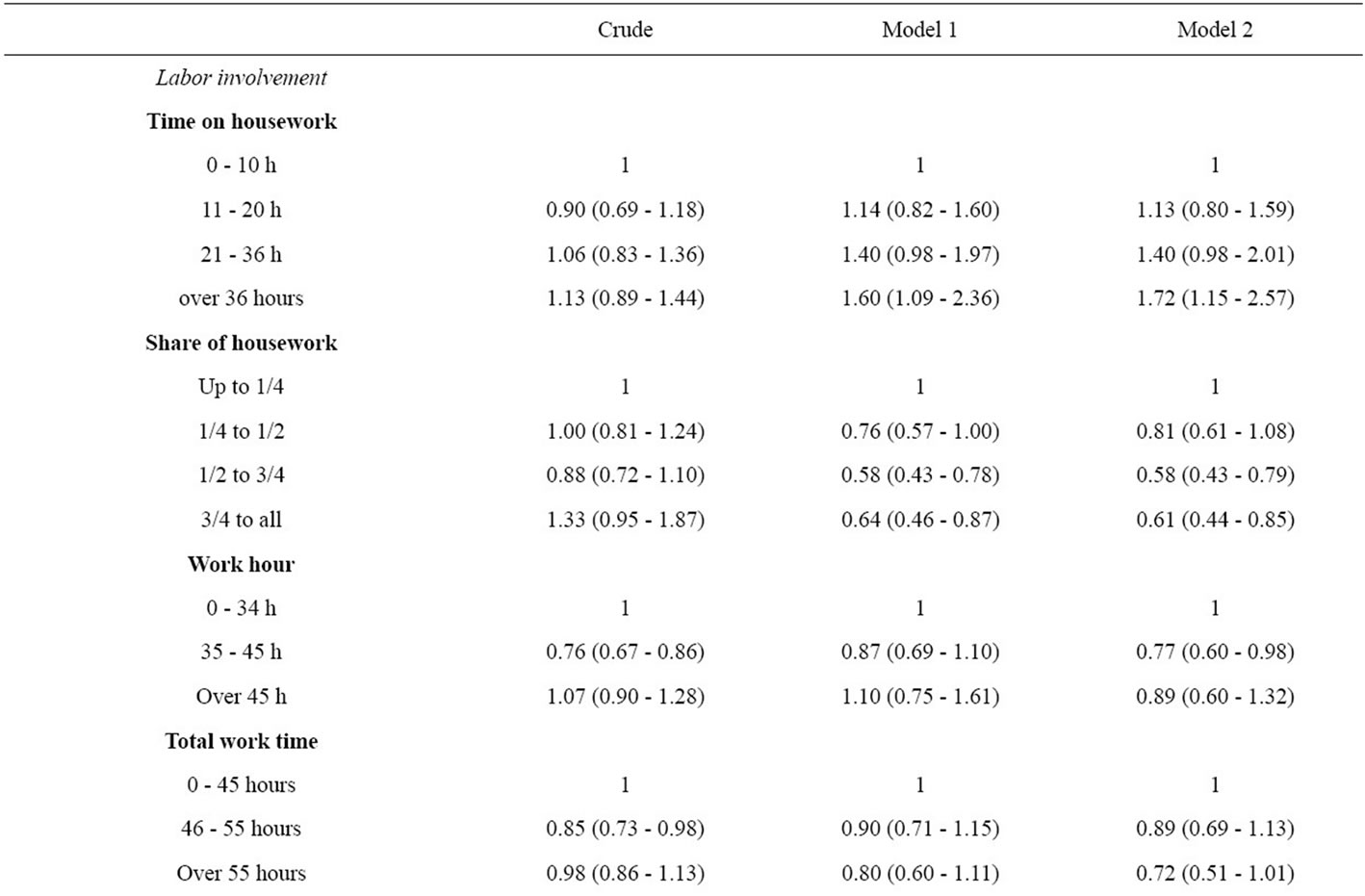

Table 3 provides the corresponding ORs (95% CI) for cohabiting or married employed women in Europe. The crude ORs show significant relationships between both work hours and total work time and a low level of perceived well-being. All variables representing labor-related stress had a significant relationship with a low level of perceived well-being.

Model 1, Table 3, shows that women who did more than 36 hours of housework each week had an increased likelihood of reporting a low level of perceived wellbeing, while women who did more than half of the housework had an increased likelihood of reporting a high level of perceived well-being.

Table 3 shows that there are small differences between Models 1 and 2 regarding the importance of labor involvement for well-being. Women who reported housework-related stress had an increased likelihood of reporting a low level of perceived well-being, but workrelated stress showed no significant relationship with well-being. Stress related to WFCs increased the odds of reporting a low level of perceived well-being 2.5 times. Disagreement had a slight impact on well-being; those who disagreed had higher odds of reporting a low level of perceived well-being.

4. DISCUSSION

This study differs from others in that we have analyzed whether actual labor involvement or labor-related stress had a greater impact on men and women’s levels of perceived well-being. We have answered our four initial questions by analyzing data from the ESS questionaire. The answer to our first question suggests that labor involvement, both paid and unpaid, does not generally influence well-being. However, women who spent more than 36 hours a week on housework and men who performed more than three quarters of the housework had significantly higher likelihoods of reporting a low level of perceived well-being. Regarding the second question, our results show that for both men and women, housework-related stress, WFCs and disagreement about the division of labor were significantly related to low levels of perceived well-being. For the third question, we found that perceptions of labor-related stress had a greater impact on well-being than actual labor involvement. Answering our fourth question, there were some differences between men's and women’s perceptions of labor-related stress and low levels of perceived well-being. Women tended to have higher odds of reporting a low level of perceived well-being when experiencing housework-related stress than men, while men had higher odds of reporting a low level of perceived well-being when experiencing WFCs.

Women’s tendency to report lower levels of well-being related to spending many hours performing unpaid work and experiencing housework-related stress could be explained by the fact that women do more of the domestic work. Previous research suggests that when men increase their share of the housework, women’s well-being will increase [4]. However, this study shows that labor-related stress is of more importance for well-being than actual labor involvement, which indicates that other more subjective factors may be of greater importance than sharing work equally. Previous research has shown that the belief that men do as many hours of housework as women can improve well-being [25]. This suggests that women who believe they share housework equally also tend to perceive their labor-related stress levels as lower. This should be investigated further. Men’s higher odds of reporting a low level of perceived well-being related to WFCs could be a result of the larger fraction of work that is paid. Working many hours could make it harder to engage in family matters and more difficult to leave work behind when coming home to the family. These results support the theory that subjective factors related to labor involvement are of more importance than actual labor involvement when studying health outcomes among women and men.

However, the results from this and earlier research show that housework is a large part of women’s workload [5,6,29] and that both the amount of time spent on unpaid work and feelings of stress related to housework tend to lower women’s well-being substantially. This implies that dividing domestic work more equally between spouses could in turn decrease women’s feelings of stress related to time spent on unpaid work and increase women’s well-being [2,4]. Furthermore, when studying the relationship between actual labor involvement and well-being, labor-related stress should be considered.

Methodological Considerations

Unlike in other studies, we found that men reported somewhat higher total work time than women [14,30, 31]. This could be a result of the questions asked to the respondents in the ESS questionnaire. Respondents were asked to approximate the total time spent doing housework and what share they did. One could stipulate that there are difficulties associated with estimating time spent on housework, both the respondent’s and his or her partner’s, because it requires that the respondents have full knowledge of their partner’s activities. For example, McDonald et al. [30] argue that partners’ reports of their spouses’ time on paid and unpaid work is on average lower than what men and women report for themselves. This could lead to an underestimation of the total time and, hence, an incorrect estimation of the share.

For the variable housework-related stress, Cronbach’s alpha was somewhat low (0.49). However, according to Pallant [32], a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.5 is relevant when the index is comprised of questions with a short answering scale.

Finally, this study was based on a large sample collected from different parts of Europe. Although there are many similarities between countries in Europe regarding the levels of involvement in paid and unpaid work among women and men, there are also some differences. Further studies that compare different countries and regions of Europe with one another regarding the relationships between actual labor involvements, perceived labor-related stress and well-being should be conducted.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Connell, R. (2002) Gender. Cambridge: Polity.

- Boye, K. (2009) Relatively different? How do gender differences in well-being depend on paid and unpaid work in Europe? Social Indicators Research, 93, 509-525. doi:10.1007/11205-008-9434-1

- Aliaga, C. (2006) How is the time of women and men distributed in Europe? Statistics in Focus, Eurostat 4/2006.

- Bird, C.E. (1999) Gender, household labor, and psychological distress: The impact of the amount and division of housework. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 32-45. doi:10.2307/2676377

- Geist C. (2005) The welfare state and the home: Regime differences in the domestic division of labour. European Sociological Review, 21, 23-41. doi:10.1093/esr/jci002

- Gjerdingen, D.K., McGovern, P.M., Bekker, M., Lundberg, U. and Willemsen, T. (2000) Women’s work roles and their impact on health, well-being, and career: Comparisons between the United States, Sweden, and The Netherlands. Women Health, 31, 1-20. doi:10.1300/J013v31n04_01

- Bird, C.E. and Fremont, A.M. (1991) Gender, time use, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 32, 114-129. doi:10.2307/2137147

- Council of the European Union (2003) Council decision of 22 July 2003 on guidelines for the employment policies of the Member States (2003/578/EC).

- Glass, J. and Fujimoto, T. (1994) Housework, paid work, and depression among husbands and wives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 179-191. doi:10.2307/2137364

- Gähler, M. and Rudolphi, F. (2004) När vi två blir tre— Föräldraskap, psykiskt välbefinnande och andra levnadsbetingelser [When two becomes three—parenthood, psychological well-being an other life circumstanses]. In: Bygren, M., Gähler, M. and Nermo, M., Eds., Familj och arbete—Vardagsliv i förändring [Family and Work— Everyday Life in Tranistion], SNS Förlag, Stockholm, 122- 165.

- Roxburgh, S. (2004) “There just aren’t enough hours in the day”: The mental health consequences of time pressure. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 45, 115-131. doi:10.1177/002214650404500201

- Boye, K. (2008) Happy hour? Studies on well-being and time spent on paid and unpaid work. Ph.D. Thesis, Stockholms Universitet, Stockholm.

- Matthews, S. and Power, C. (2002) Socio-economic gradients in psychological distress: A focus on women, social roles and work-home characteristics. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 799-810. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00110-1

- Väänänen, A., Kevin, M.V., Ala-Mursula, L., Pentti, J., Kivimäki, M. and Vahtera, J. (2004) The double burden of and negative spillover between paid and domestic work: Associations with health among men and women. Women & Health, 40, 1-18. doi:10.1300/J013v40n03_01

- Bahr, S.J., Chappell, C.B. and Leigh, G.K. (1983) Age at marriage, role enactment, role consensus, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 795- 803. doi:10.2307/351792

- Gutek, B.A., Searle, S. and Klepa, L. (1991) Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 560-568. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.76.4.560

- Canivet, C., Ostergren, P.O., Lindeberg, S.I., Choi, B., Karasek, R., Moghaddassi, M., et al. (2010) Conflict between the work and family domains and exhaustion among vocationally active men and women. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 1237-1245. doi:10.1016/j.socsimed.2009.12.029

- Sabbath, E.L., Melchior, M., Goldberg, M., Zins, M. and Berkman, L.F. (2011) Work and family demands: Predictors of all-cause sickness absence in the GAZEL cohort. The European Journal of Public Health, 22, 101-106. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckr041

- Harryson, L., Novo, M. and Hammarström, A. (2012) Is gender inequality in the domestic sphere associated with psychological distress among women and men? Results from the Northern Swedish Cohort. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 66, 271-276. doi:10.1136/jech.2010.109231

- Lennon, M.C. and Rosenfield, S. (1994) Relative fairness and the division of housework: The importance of options. American Journal of Sociology, 100, 506-531. doi:10.1086/230545

- Nordenmark, M. and Nyman, C. (2003) Fair or unfair? Perceived fairness of household division of labour and gender equality among women and men. European Journal of Womens Studies, 10, 181-209. doi:10.1177/1350506803010002004

- Centre for Comparative Social Surveys at City University, et al. (2010) European social survey. http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/

- Löwe, B., Spitzer, R.L., Gräfe, K., Kroenke, K., Quenter, A., Zipfel, S., et al. (2004) Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 78, 131-140. doi:10.1016/S01065-0327(02)00237-9

- Boye, K. (2011) Work and well-being in a comparative perspective—The role of family policy. European Sociological Review, 27, 16-30. doi:10.1093/esr/jcp051

- DeMaris, A. and Longmore, M.A. (1996) Ideology, power, and equity: Testing competing explanations for the perception of fairness in household labor. Social Forces, 74, 1043-1071. doi:10.2307/2580392

- Greenstein, T.N. (1996) Gender ideology and perceptions of the fairness of the division of household labor: Effects on marital quality. Social Forces, 74, 1029-1042. doi:10.2307/2580391

- Nordenmark, M. (2004) Does gender ideology explain differences between countries regarding the involvement of women and of men in paid and unpaid work? International Journal of Social Welfare, 13, 233-243. doi:10.1111/j.1369-6866.2004.00317.x

- International Statistical Institute (2010) ISI decleration on professional ethics. http://isi-web.org/about/declarationprofessionalethics-2010uk.

- Boye, K. (2010) Time spent working. Is there a link between time spent on paid work and housework and the gender difference in psycological disterss? European Societies, 12, 419-442. doi:10.1080/14616691003716928

- MacDonald, M., Phipps, S. and Lethbridge, L. (2005) Taking its toll: The influence of paid and unpaid work on women’s well-being. Feminist Economics, 11, 63-94. doi:10.1080/1354570042000332597

- Hochschild, A. and Machung, A. (2003) The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. Penguin Group Inc., New York.

- Pallant, J. (2010) SPSS survival manual—A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS. 4 Edition, Open University Press, Maidenhead.