Current Urban Studies

Vol.04 No.01(2016), Article ID:64774,16 pages

10.4236/cus.2016.41005

COFOPRI’s Land Regularisation Program in Saul Cantoral Informal Settlement: Process, Results and the Way Forward

Seth Asare Okyere1, Karenina Aramburu2, Michihiro Kita1, Haroon Nazire1

1Division of Global Architecture, Graduate School of Engineering, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan

2Department of Architecture and Urban Studies, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 4 February 2016; accepted 18 March 2016; published 21 March 2016

ABSTRACT

The need to address the challenge of urban informal settlements has led a number of formalization programs over the past few decades. In this paper, we focus on the land regularization program implemented by COFOPRI in Saul Cantoral informal settlement in Lima, Peru. The study sought to understand implementation interventions and current conditions following state land regularization program in the study area. Qualitative methodologies such as unstructured interviews, observation and photography were used. The study revealed that land title promoted gender inclusiveness and enhanced tenure security. However, economic and social integration of informal residents were far from realized. Rather, social, environmental and infrastructural conditions have worsened. The study suggests the need to revise and integrate land regularization into the urban development planning process of the settlement through collaborative planning.

Keywords:

Informal Settlements, Formalisation, Land Title, Urban Development Planning, Saul Cantoral

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, there have been consistent global efforts aimed at improving human settlements. These are often situated within the terminology of “sustainable human settlements” (UN DESA, 2015) . Traces of these can be found in the 1996 Habitat II Conference, Rio+20, Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and more recently the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Informal settlements remain central, with an ambitious goal of “eradicating informal settlements” through the support of international aid agencies and bilateral organizations (Hermanson, 2016) . The focus has been to build on global agenda to address the so-called informal settlement or slum problem (Lombard, 2014) ; geographically positioned in the global South (Roy, 2011; Watson, 2009) and tackled with a garment of neoliberalism ( Obeng-Odoom , 2015;

In view of this, formalization policies and projects over the past decades appeared to be a highly favored program, implemented as a solution to the crisis of urban informality and slumming of cities in the developing world. It has been largely implemented in Latin American states (Abbot, 2002) , known to be among the hotspots of informal settlements (Varley, 2013) . However, the upsurge in urban informal settlements has made the role of formalization policies suspect among postcolonial scholars and researchers. It is estimated that over one billion people now live in “squatter”, “slum” or “informal” settlements globally, a population that is projected to grow to 1.4 billion by 2020 (UN-Habitat, 2006) . Again, urban informality is considered as the dominant “mode of urbanization” (Roy, 2005, 2011) . The population living in informal settlements is expected to “surpass or equal” those in formal settlements, making it the dominant form of urbanism (Gouverneur, 2015: p. 6) . If these trends are considered, it becomes of actors, researchers and scholars to take a critical look at the approaches that have been adopted over the past decades in dealing with informal settlements as well as the conceptual and political narratives that underpin their formulation, implementation and evaluation (see Gilbert, 2002 ).

The aim of this paper is therefore to contribute to the growing literature in urban studies emphasizing the need for rethinking urban informal settlements and the mechanisms for their improvement (see Gouverneur, 2015; Obeng-Odoom, 2013, 2015; Okyere & Kita, 2015; Varley, 2013; Lombard, 2014; Huchzermeyer, 2004; Gilbert, 2002 ). It does this by focusing on formalizing program in the Saul Cantoral Informal area (Lima), which has been implemented through a coordinated program of state and private agencies. It follows Abbot (2002) proposal that “origin of the intervention is less important than the substantiation of the results of the intervention”. This paper documents the process of the land regularization program and results, and then makes important suggestions to advance the development of the Saul Cantoral informal settlement.

2. Formalization Approaches to Informal Settlements in Latin America

Since the discussion on urban informality and informal settlements emerged in the 1950/60s, it has been commonly agreed that there is a significant need to improve the state of housing for the urban poor. To this end, intervention measures to address the problem of inadequate housing have been addressed from different points of view (Wekesa et al., 2011: p. 341) . Again, the failure of “demolition and replacement” by public housing (Abbot, 2002: p. 306) ―which was the dominant state-centered approach in the 1960s―to eventually eliminate informal settlements, led to a shift to formalization policies that recognize the autonomy and control inherent in the production of public housing ( Turner & Fichter, 1972; Pugh, 1995; in Abbot, 2002: p. 306 ) in developing countries. Here, we underline some of the common formalization practices in Latin American context.

2.1. Legal Recognition

This policy has been to recognize or legalize informal land development, especially in relation to the practice of squatting, through juridical-administrative tools (e.g. indemnity, regularization procedures for titling) or through public policy (amnesty). Legal titling is primarily based on De Soto’s (1984, 2000) celebration of the informal residents, the so-called urban poor, as heroes of their own housing destiny. In his argument, granting title deeds, as a regularization or formalization program, resurrects the “dead capital” of informal residents that provides a way out of poverty through the credit markets. Titling thus enables informal residents to enter the formal market, obtaining the necessary capital to address poverty and informality by improving their homes, obtaining security of tenure and contributing to the overall economy. This has been influential in Latin American countries, leading to formalization programs in Peru, Colombia and Brazil among others. However, this policy has been criticized as oversimplification of the relationship between informality and poverty (Obeng-Odoom, 2013) and an incentive for illegal occupation ( Fernandes , 2011;

2.2. Settlement Upgrading

Upgrading is seen as any sector-based intervention in a settlement that results in “quantifiable improvement in the quality of life of residents” (Abbot, 2002: p. 307) . This approach is rooted in the work of Turner (1968) who was among the first to suggest that dweller control in housing was important. His idea on the desire of families to house themselves and the lack of political will, led to the “self-help” concept in the 1960s and 70s (Lombard, 2014: p. 8) . This became very influential and popular, through the World Bank’s site and services and upgrading schemes. Championed by international agencies and national governments, it involves improving and/or installing basic infrastructure such as water, sanitation, solid waste collection, access roads and footpaths, storm water drainage, electricity, and public lighting ( Imparato & Ruster, 2003: p. 2

2.3. Urban Redevelopment

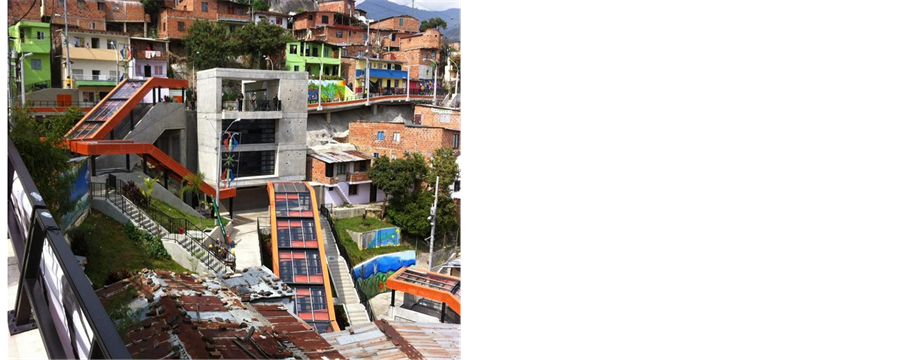

This involves on-site redevelopment through gradual demolition and in-situ construction of alternative housing; which is clearly government policy response to guarantee security (Fernandes, 2011) . It usually targets deteriorated and vulnerable informal areas, were housing conditions are unsafe and close to vulnerable urban areas. There are few pilot projects of this type in Latin-American countries implemented by leading NGOs that are capable of mobilizing government support and ensure the interest of residents. There is also another variant of this program, more aggressive and involves complete demolition. This is applied in hazardous squatting informal settlements, under the justification of environmental and public health concerns or the need for public spaces (Gouverneur, 2015) . However, recent laws have barred such practices. In Colombia, Argentina and Brazil for example, public and private owners are given alternatives to negotiate with informal residents to help maintain existing social networks. It is worthy to note that the lack of appropriate understanding on the formation and consolidation of informal settlements, in addition to corruption, segregation and limited participation has impeded the success of such formalization programs over the past decades (Fernandes, 2011) . Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate pictorially, examples of the approaches aforementioned.

3. COFOPRI and the State Land Regularization Program in Peru

In the mid 1990s, a national policy was formulated―which was later translated as a legal instrument―to allow the integration of well-established informal settlements in Peru, especially Lima. This policy, known as the “Land Titling Program” was a bold political attempt at formalization of informal settlements in Peru. The policy was largely a product of the Economist Hernando de Soto’s idea that land titling and registration would enable informal occupants to access formal credit and finance housing and business investment. This was viewed as a necessary condition for reducing poverty and improving informal settlements (De Soto, 1984) . Since 1996, there has been a large-scale application of the Land Titling Program in Peru. This emerged through the establishment of the Commission for the Formalization of Informal Property (COFOPRI), tasked with exclusive and excluding functions for the implementation of the Titling program. The project received support from The World Bank,

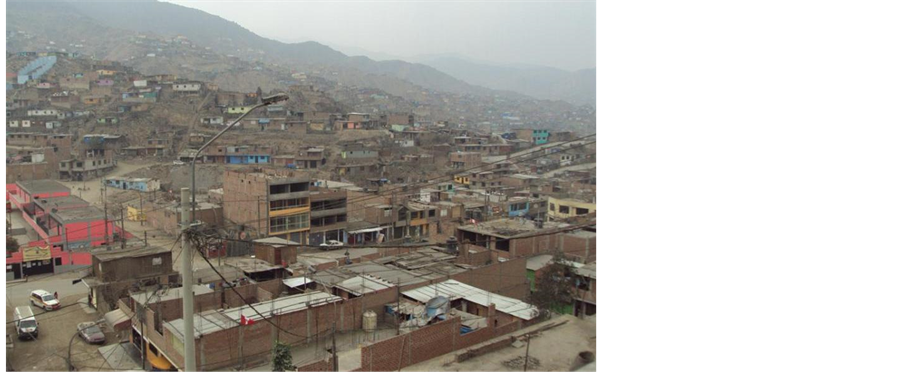

Figure 1. Legal recognition or land titling.

Figure 2. Settlement upgrading program.

Figure 3. Urban redevelopment program.

UN-Habitat, the Institute for Liberty and Democracy (De Soto’s institution) and the United States Agency of International Development (USAID).

COFOPRI as a stakeholder and administrator was created as a decentralized Public Institute subject to regulations applicable to public entities, with its own endowment, administrative, technical and economic autonomy. COFOPRI was also established as an Executive Branch Agency, with members appointed by the President of Peru and chaired by one minister of State appointed by the President. Currently, the Minister of Transportation, Communications and Housing chairs the institution. A National Coordinator appointed by the President leads COFOPRI (responsible for the massive land tenure regularization program) and the Urban Registry (RPU, responsible for the registration of all the properties generated by the massive land tenure regularization program).

The aim of the Land Tenure regularization program is the social and economic integration of the low-income people, with proper recognition of the savings and investments made on the sites they occupy, as well as the worthiness of their properties through titling. It is therefore implied that properties owned by the low income informal sector could be integrated into the real estate market and thus, become more tradable. The first step for achieving this objective was to implement a comprehensive, integral and expeditious land regularization program.

COFOPRI implemented a number of strategies which included 1) institutional reforms, 2) community participation, 3) securing land rights and value, 4) simplifying administrative procedures, 5) creating incentives for keeping transactions of regularized properties, 6) design a fast, massive sustainable system for land regularization, and 7) promote stakeholder collaboration. The main actors and their roles in the design and implementation of the program are presented in Table 1.

3.1. Aspects of the Land Regularization Program

COFOPRI’s system for the implementation of the land regularization program involves four main aspects: campaigns, general strategy, titling procedures and application of system tools.

3.1.1. Campaigns

This is the first stage of the land titling process, where campaigns are undertaken as mass awareness exercises. Each campaign takes about 2 months to complete, involving 50 to 70 informal areas, constituting about 30,000 to 35,000 plots. During the campaign, the focus areas considered for land regularization were selected based on different criteria that includes 1) feasibility for formalization, 2) geographical situation in terms of overlaps with state/private/mining lands or sensitivity in terms of archaeological or security concerns, 3) informal dwellers requests, 4) existing legal and technical documents, and 5) linkages with other institutions among others.

3.1.2. General Strategy

COFOPRI in conjunction with other responsible agencies (see Table 1) conducts legal and physical surveys of the areas involved in the campaign. Again, institutional assessment is undertaken to examine its capacity to formalize the area in terms of the topographical and cadaster data required and the legal framework needed for the process. Based on the results of this assessment, a community mass mobilization exercise is undertaken to inform residents of the formalization process and engage them. An actor collaboration and coordination mechanism is employed to assure a fast and efficient formalization program.

3.1.3. Titling Procedures

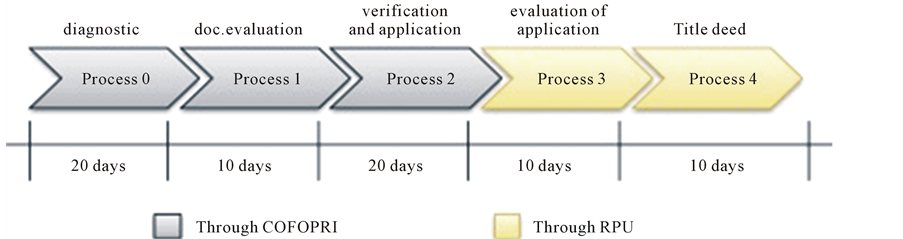

Procedures for granting the title deed is organized into five phases that take approximately 70 days to complete.

1) Diagnostic phase: This involves the actual identification of and information on informal settlements in the selected areas in terms of socio-physical characteristics.

Table 1. Actor roles in the land titling program.

2) Settlement evaluation: Includes physical and legal analysis of individual settlements to determine constraints to their formalization. For example, if they are located on public land or private property. The final output of this phase is a layout plan and cadaster drawing which is eventually registered at the Urban Registry of Properties (RPU).

3) Verification and application: This stage is organized in the form of door-to-door census, where residents are informed on the scope and the documents required for regularisation.

4) Evaluation of Application: In this phase, all applications documents are assessed to ensure that the necessary requirements are met.

5) Granting Title deed: This is the final phase and the output of the entire titling procedure. The title deed is formally granted to the informal residents and archived as registered property.

3.1.4. Tools

COFOPRI adopts specific tools for the implementation of the Land Title Program. Information Management System (IMS) is used to organize all relevant data (including social, physical, geographical database) about residents for the registration and improvement of settlements. Geographic Information System (GIS) is especially utilized for processing geographical data for the spatial organization of selected areas.

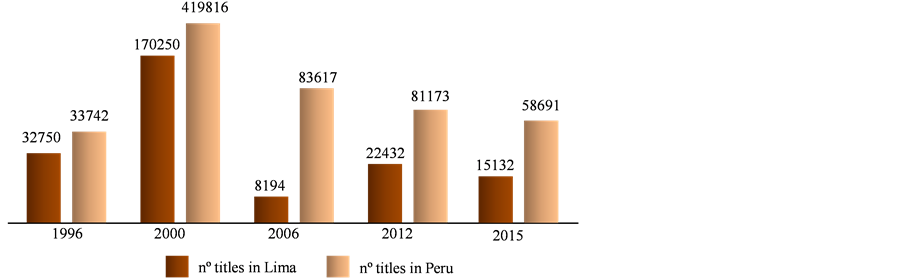

3.2. Distribution of Title Deeds

COFOPRI, since leading the land-titling program in 1996, has been instrumental in the formalization of informal settlements in Peru, especially the Lima Metropolitan Area. It has covered about 90 percent of all informal properties and 95 percent of cadaster data processing for all cities. The agency has also been crucial in simplifying the land titling registration process from 7 years to 3 months or less (shown in Figure 4). In Metropolitan Lima alone, about 700,000 title deeds were granted between 1996 and 2006 (COFOPRI, 2011) . As observed in Figure 5, title distribution was much higher before 2006 as compared to post-2006. This was due to the political support for formalization, particularly in the Fujimori era. This has changed recently; partly due to the transfer of formalization responsibility to local municipalities and the fact that COFOPRI’s mandate was intended to finish in 2012.

Figure 4. Phases of the land titling program (source: Authors’ elaboration, 2015).

Figure 5. Land titles distributed between 1996 and 2015 (source: www.cofopri.gob.pe, 2015).

4. Research Setting and Methodology

Lima city is a viable context to examine approaches towards informal settlements. It has about 55 percent of its population (almost 10 million people) living in informal settlements. The San Juan of Lurigancho district (where the case community is located) is the largest informal settlement in Lima, with an estimated population of 2 million people. This began in 1940 to the 1970s, when several migrants occupied public land and big extensions of private land that was mostly designated for planned urban expansion. During this period, many informal settlers constructed houses, roads and facilities. Again, the political agenda at the time, which led to the centralization of all services in the capital, such as the possibility of better economic and employment opportunities (e.g. education, health care, infrastructure, etc.) and the location of the government bureaucracy pushed people to move from provinces of Peru to Lima. An industrialization model based on centralized economic growth drove rapid urbanization in the city of Lima (King, 2003; Riofrio, 2008) .

Furthermore, the wave of rural violence between the 1980s and 1990s, fueled by the guerilla group “Sendero Luminoso” caused a tremendous wave of violence especially in rural areas outside Lima. This violence produced a massive displacement of people from different parts of the country into the city for protection (Riofrio, 2008) . During this wave of violence, many “pueblos jovenes1” or “asentamientos humanos” that developed in the peripheral areas of Lima, became part of the urban nodes called “conos”2. Informal settlements therefore emerged in less attractive areas with unsuitable geophysical conditions―characterized by total lack of public services and self-made dwellings. Recently, the high cost of land development and constraints in the formal market has also pushed several people into informal areas (King, 2003) .

This study was conducted in the Saul Cantoral Informal Settlement. The settlement is located on the periphery of Lima, the capital of Peru. The area was selected due to its secured nature and relation to the capital city-Lima. It is also one of the first informal areas to be formalized, nearly 20 years ago, giving ample opportunity to qualitatively understand the formalization process and the post-formalization conditions. A qualitative methodological approach was adopted for the study. A total of 50 household heads were interviewed through unstructured questionnaires. These were supported with observation, photography, discussions, secondary data collation and 5 expert interviews (two officers from COFOPRI, two founders of the settlement and one opinion leader). This made it possible to explore what Herbert (2000: 552) refers to as activities and symbolic constructions and the discrepancies between thoughts and deeds. It allows the opportunity to move beyond statistics and figures to understand everyday life needed for capturing the multi-faceted nature of a place as a socio-spatial concept (Lombard, 2014: p. 6; Hardoy & Satterthwaite, 1989) .

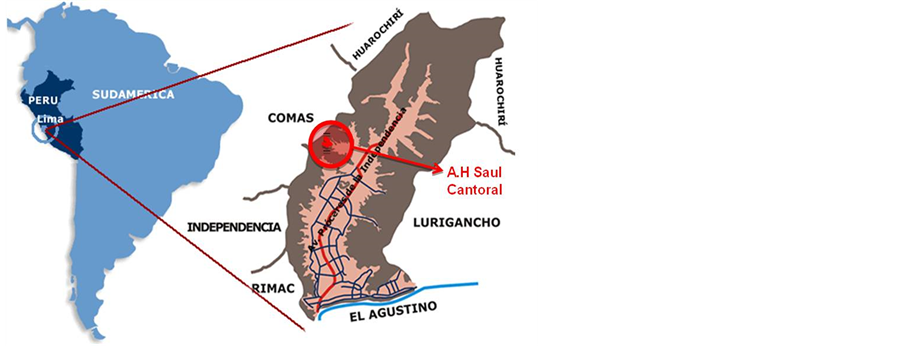

5. Case Study: A.H. Saul Cantoral Informal Settlement

A.H. Saul Cantoral informal settlement is located in the district of San Juan de Lurigancho, which is in the east cone of Lima (Figure 6). The district of San Juan de Lurigancho is the biggest district with 15 percent of the total population of Lima. The A.H. Saul Cantoral informal area was founded in 1990, when 31 people3, mainly from the southern part of Peru, came together to form the settlement by soliciting funds and pooling resources to clean the area―which the Empresa Nacional de Edificaciones (ENECA)4 previously used to deposit waste from the construction of social housing for the police force―and level the land (shown in Figure 7). In October 1993, the area was legally recognized by the Municipality of San Juan de Lurigancho as the “Saul Cantoral Human Settlement”, accompanied by a perimeter plan with a total area of 155,759.24 m2. The area was included in COFOPRI’s land regularization/formalization program in 1998.

Overview of Physical and Social Conditions

The current population according to local district figures is estimated at 5000 inhabitants. The survey revealed that the average household size is 5.7. Again, 60 percent of the interviewed households are in the school going age of between 6 and 16 years, implying a generally young populace. Women were an active population in

Figure 6. Saul Cantoral informal settlement in Lima metropolitan area.

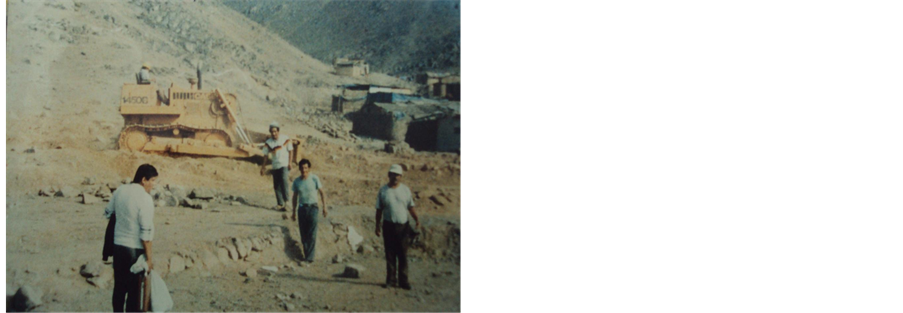

Figure 7. Early Settlement formation in the 1990s.

generating incomes, usually involved in informal economic activities on site, specifically in trading of small-scale grocery or food stores. In terms of physical appearance, most of the settlements are located on hillsides, usually hazardous, with slopes ranging between 30 and 50 percent. Within this range, the survey indicated that about 40 percent of all plots are located on high-risk zones with slopes above 40 percent. This topography allowed vehicular access only to the lower parts of the settlement. Vehicle and pedestrian access to the settlement could be traced but dust was a problem since roads were not paved. Foundations are mostly “pircas”5, made of stones. Electricity was available within the settlement but not sewerage services.

Community leaders, in an effort to narrate the conditions of the Saul Cantoral informal settlement before formalization program, provided old pictures as pictorial records on the formation and development of the settlement. Figure 8 records the main street to the informal area and the precarious construction materials used for house construction, while Figure 9 shows the community water facility and the social activity that existed in the settlement before the formalization program was completed.

6. Implementation of the Land Tenure Regularization Program in Saul Cantoral

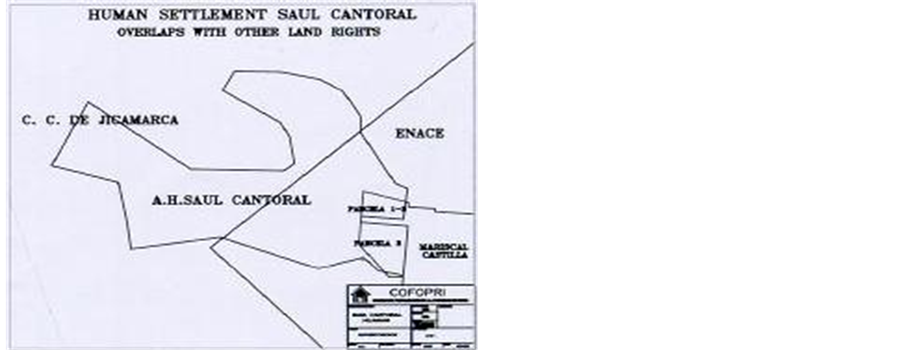

The previous section has presented the institutional framework and mandate of COFOPRI in the general land regularization program in Peru. Before we highlight the specific interventions and the results in case study area, it is worthy to mention some problems that existed before the intervention program commenced. First, the area was legally recognized by the municipality in 1993 but never registered in the Urban Registry of Properties (see

Figure 8. Conditions in early settlement formation period.

Figure 9. Conditions before formalization program.

Table 1). Second, the area overlapped with the coastal peasant community of Jicamarca, and ENACE site (an area reserved for recreational facilities in the Municipal Housing Program: “Mariscal Castilla”). Thirdly, there was a lack of official coordinates in the Perimeter plan approved by the Municipality of San Juan de Lurigancho. Fourthly, the perimeter plan did not represent the actual boundary of the settlement, since new informal areas were not considered. Lastly, subdivisions did not correspond to real plot dimensions. Local government also showed indifference toward the improvement of informal settlements in the area. Appearing to support the integration of informal areas, yet ignoring critical considerations in terms of physical planning as evident in Figure 10.

Specific Land Regularization Actions in the Area

In view of the aforementioned challenges, the survey revealed that COFOPRI implemented a number of actions to provide the base conditions for the land regularization program:

・ The transfer and inclusion of the ENACE site into the Saul Cantoral area through an agreement between COFOPRI and ENACE.

・ A new perimeter plan was prepared to adequately integrate geographical data and other official maps of the area. The former subdivision plan was therefore carefully updated.

・ In consultation with the National Defense council (INDECI, see Table 1), settlements in landslide prone or high-risk areas were permitted to stay. This was based on the agreement that civil works will be undertaken to prevent landslides or associated natural disasters.

・ Since the informal area had no records in the urban registry, the new perimeter plan and plots that had obtained legal and technical regularization were registered at the urban registry of properties.

・ Resident participation was promoted during the regularization process, especially in areas where settlements were affected. For instance, a communal decision was made to change land use from recreation to residential in order to include households occupying areas reserved for parks.

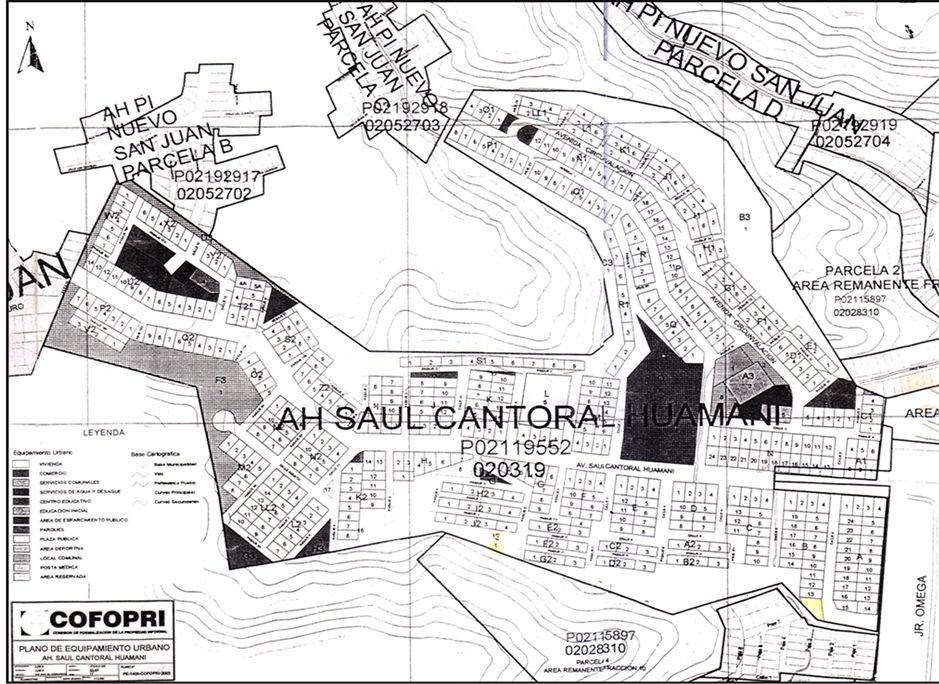

These activities were organized as part of the broader regularization program to formalize the entire informal area. Eventually, the field survey indicated that the titling program delivered 496 titles in the Saul Cantoral informal settlement. Again, the new urban plan (shown in Figure 11) reserved 22 plots for community facilities and commercial functions.

Figure 10. Saul Cantoral overlapping with other sites (obtained from cadaster office of COFOPRI, 2010).

Figure 11. Final urban plan of Saul Cantoral informal settlement (obtained from founding leadership, dated 1999).

7. Results of COFOPRI’s Land Regularization Interventions

Following the interventions by COFOPRI, we turn attention to current conditions in Saul Cantoral informal settlement. Here, through field observation and resident narratives, we underscore the effects of the land regularization program in terms of social-cultural, economic, environmental and infrastructure aspects.

7.1. Socio-Cultural Aspects

Although all the 496 title deeds were distributed to the qualified households, one significant aspect that was highlighted during field interviews was the “gender inclusiveness” of the land-titling program. That is, title deeds were given to both men and women in the households, even in situations where couples had stayed together for a long period but not legally married. This was a major improvement, women householders asserted, as it assured them of property ownership and provided economic and social security. Culturally, this gender sensitivity in the land-titling program is peculiar, especially in an area where social relations are very male dominating and paternalistic, depriving women of asset creation and economic empowerment. Residents also revealed that formal titles have supported tenure security and reduced threat and fears of eviction. They feel more secure, as holding titles provided them the legal and technical capacity to contest claims of ownership or other associated litigations. This might explain why households indicated that social conflicts and litigations over land rights or ownership and boundaries have virtually disappeared after obtaining title deeds.

On the contrary, local leaders indicated that there has been a gradual decrease in socio-cultural programs in the municipality after residents obtained title deeds. Silva, a leader and founder of the settlement, highlighted this as a negative trend in their post-titled deed experience:

“Before the residents were given land title, there was a good cooperation and participation in community activities. Residents met frequently to organize events and discuss issues for community improvement. But people chose not to cooperate after COFOPRI granted title deeds. There is no participation unless there is a political program to distribute rice or milk.”―(Silva, 10.08.15)

This response implies that people have become more individualistic and less concerned by the communal issues after obtaining title deeds. Contrary to the common notion of strong participation built on informal networks in such areas, this finding suggests that residents, focusing on the prospects of property ownership and capitalizing on their individual assets, prefer to think and act individually for personal benefit than common good. Local leaders frequently lamented this. Moreover, even though residents have obtained title deeds and had become a “formalized” and integrated area within the municipality, dwellers hinted of persistence “distance and discrimination” (Lombard, 2014) . To describe how they felt and were perceived by other residents within the municipality, one householder explicitly stated:

“There is still stigmatization of this formalized area as second rate. People in Saul Cantoral are treated as second rate residents in second rate area of the city.”―(Lucero, 11.10.15)

This account expresses the status of the Saul Cantoral area, although they have been formalized and registered in the urban registry as a legal part of municipality, it has not contributed to perceptive and negative constructions by other residents in the municipality. This could be attributable to the social isolation of the settlement, seen in the lack of adequate facilities and services (discussed below) for basic human comfort.

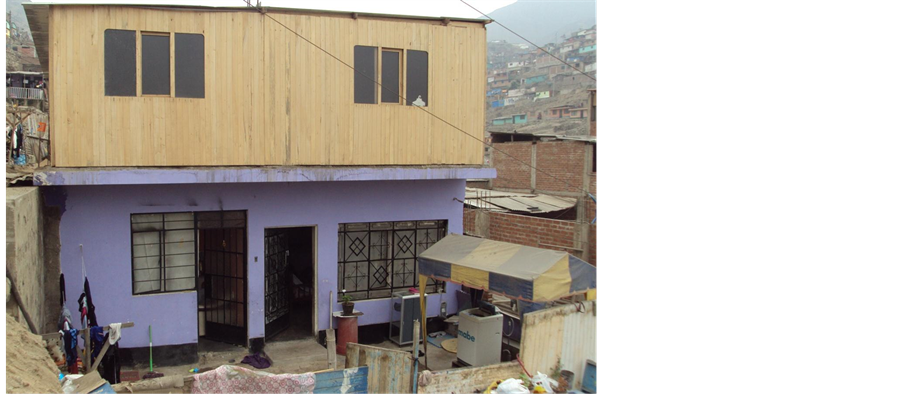

7.2. Economic Aspects

Residents, though unwilling to disclose actual incomes, indicated that they have observed increases in their incomes of between 20 and 30 percent after obtaining titled deeds or being regularized. These increases in incomes, according to 30 percent of the residents, came from sales of a portion of their plots to new residents in the community. The remaining (70 percent) came from renting part of their rooms to other residents in the settlement. Density has increased; resulting in an observable congestion that rarely eases permeability and accessibility (Figure 12(a) and Figure 12(b)). The study also revealed that the extra income from rent was used for two main purposes: improving the condition of houses with permanent and durable materials (50 percent) and establishing shops or other income generating activities in the settlements (50 percent). However, none of the households hinted of receiving credit from any of the private banks in the municipality. One resident disappointingly claimed:

Figure 12. (a) Increased Density due to subplot sales (authors own picture, 2015); (b) Additional floor space to an existing house using income from subplot sales (authors’ own picture, 2015).

“Private banks are afraid to lend to risky low income people from Saul Cantoral area.”―(Cesar, 11.08.15).

This remark is telling, as it seems to defeat the aim of the regularization program that title deeds will provide access to credit, thereby enabling capital accumulation for addressing poverty and improving housing conditions. Indeed, there is evidence of residents improving their houses, but this has been the result of income from their own commercial activities than credit obtained from financial institutions. Economic integration of informal residents into the formal credit market was rarely existent in this study.

7.3. Environmental Aspects

The topography of Saul Cantoral is hilly, with about 40 percent of residents residing in areas with slope above 40 percent. Thus, close to half of the residents are prone to landslides or other associated natural disasters. During the land regularization process, settlements in such hazardous areas were not relocated due to the agreement that the National Defense Council’s (INDECI) recommended civil works on the hillsides and disaster prone areas will be implemented. However, it was observed during the research that no such works have been undertaken. Rather, and more problematically, there were several land invasions and squatting, occurring even in hazardous areas (Figure 15). These unfriendly practices have been fueled by illegal subdivision of regularized land and sale of plots, prohibited under the regularization program. Again, houses in these hazardous areas were built with timber, plastic or mats with “pircas” foundations that made them susceptible to harsh weather effects and disasters (see Figure 13). In environmental terms, it can be inferred that there have been so significant improvement, especially considering the topography of the settlement and necessary actions that need to be taken. Land titles and the regularization program have indeed secured tenure, but it has not secured environmental conditions and disaster risk in the settlement.

7.4. Community Infrastructure, Facilities and Services

In Figure 11, we showed the urban plan prepared by COFOPRI, in collaboration with other stakeholders (Table 1), to guide the development of the settlement. On-going field developments however revealed striking disparities in comparison with the urban plan. For example, areas designated for parks or green areas in the original urban plan have seen no development, either remaining empty spaces or under encroachment by new informal settlers (Figure 14 and Figure 15), impeding spatial organization and harmonious development of the settlement. Even the areas assigned for community parks and garden (3.8 percent) are not within the acceptable national standard of 6 to 8 percent. Moreover, provision of basic infrastructure facilities and services is poor; roads are still unpaved and dusty, limiting vehicular accessibility. Lack of community facilities such as health center,

Figure 13. Houses in Hazardous areas with “pircas” foundations (authors’ own picure, 2015).

Figure 14. Proposed park area now deserted.

Figure 15. New informal land use practices appearing in the area (authors’ own picture).

market and schools still characterize the settlement. One of the local leaders, Giron, lamented, what is succinctly the current condition of facilities and services:

“Some people with power (municipality and private entities) bought some of this community plots to use them for other activities for their own benefits, such as private schools or religious activities. Furthermore, right now we do not have a health center. The plot designated for health service has no infrastructure at all. We asked the health ministry to provide us support, especially for doctors, but until now, it has halted because of bureaucratic procedures. The same authorities turned their back to us. The closest health center is located 3 Km from A.H. Saul Cantoral. The first attempt to get a health center was after the formalization process, in 2003, they told me to coordinate with the authorities, so more bureaucracy and no actions. After that I decided to return again in 2007 and 2010, but again it was the same story because of governmental changes. Even our community food center has closed since 2005.”―(Giron, 11.08.15).

This vivid narrative underscores residents and community leaders enthusiasm to secure the provision of basic services following the formalization program. This may be due to their belief that formalization was one of the surest ways of obtaining basic services from the municipal government. The actual situation has however proven contrary. On the other hand, it also demonstrates local government ambivalence toward the Saul Cantoral informal area. Although the municipality supported the regularization or titling program, it has not demonstrated the will or provided support for the socio-physical improvement of the formalized area. Thus, in the report above, local leaders imply ineffective urban governance―that development of the settlement depends significantly on the political and technical response from local state authority, who wield the power to determine the state of affairs and its progress.

8. Concluding Remarks

As stated in the introduction to this paper, land title regularization has been a bold attempt to address the challenge of urban informal settlements in Peru. The study has revealed that indeed land title deeds have provided tenure security to residents and allayed fears of eviction―an incentive for residents to improve their housing conditions. This has been evident, as about 50 percent of residents have improved the condition of their houses through savings. However, residents revealed that title deeds have not enabled them to access the credit market or obtain the necessary capital for addressing poverty, defeating the economic integration aim of the state regularization program. Again, formalization has not enabled the provision of social facilities and services like health center or physical infrastructure such as roads. Land invasion, illegal plot sales are rather increasing, implying new informal practices in a formalized area. Land titles have promoted individualization and collective efforts, eventually leading to the gradual decline in socio-cultural programs and events in the community.

Based on the findings, we assert that though land regularization is useful, and it does not does provide the necessary inputs for improving conditions in informal settlements and for residents. To enhance prospects and address weaknesses in the program, the following suggestions are made.

・ Integrate land titling/regularization in the urban development planning of the settlement. It is important to conceive land titling not as a single formalization approach for informal settlement improvement. Instead, it should be connected to the urban development planning of Saul Cantoral. Thus, land titling becomes the first part of the process for addressing the physical, social, infrastructure and environmental needs of informal areas. This, accompanied by a consultative and participatory urban development plan, which is currently absent, will provide a holistic framework and plan of action for promoting sustainable settlement improvement in Saul Cantoral informal settlement.

・ Redefine the institutional framework for the formalization program in Peru. A fundamental problem in the implementation of the land-titling program was the relative functional monotony of the agencies involved in the program. Most of the agencies were land sector agencies or associated to land and safety and hence had limited post-formalization roles. Critical service agencies such as health, transport, education, local economy and social welfare were not actively involved in the implementation. This explains why formalization has not addressed the social and infrastructural needs in the Saul Cantoral area. A redefinition of actors and the opening up the actor network to include all the necessary agencies should be promoted. This will ensure access to basic facilities and services and eventually the social integration of Saul Cantoral residents.

・ Revise the urban plan for the settlement. Even though practices and activities on the ground have not reflected proposals in the original urban plan, there has been no revision or update since it was prepared in 1999. The plan is no longer a relevant physical document, in terms of field experiences. A major update is necessary. COFOPRI, in collaboration with residents, municipal authority and all other relevant sector agencies should update and improve the plan to reflect current demands and situations. This could include redefining minimum standards, procedures and new context-specific guidelines for improving the area.

・ Promote collaborative planning. COFOPRI together with the San Juan de Lurigancho municipal authority should involve professional organizations, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and citizen groups to strengthen participation and cooperation in planning and developing Saul Cantoral. Encouraging community participation through citizen groups and integrating resident inputs and activities will be vital in revitalizing communal activities in the area. This may imply introducing social and cultural events (e.g. community sports programs) that have the tendency to evoke cooperative actions among residents. Again, by promoting civil society activities in the area, local participatory activities can be strengthened for the general benefit of the residents. Moreover, COFOPRI and the municipality can tap into the knowledge and competencies of local private organizations and professional bodies (e.g. universities and professional associations) to create bracing networks of support. This can provide technical expertise (or support) for improving current conditions in the Saul Cantoral informal settlement.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to A.H. Saul Cantoral community leaders and respondents for their time and patience during the interviews. We also appreciate the kind assistance of COFOPRI staff and local property experts interviewed during the field survey.

Cite this paper

Seth AsareOkyere,KareninaAramburu,MichihiroKita,HaroonNazire, (2016) COFOPRI’s Land Regularisation Program in Saul Cantoral Informal Settlement: Process, Results and the Way Forward. Current Urban Studies,04,53-68. doi: 10.4236/cus.2016.41005

References

- 1. Abbot, J. (2002). An Analysis of Informal Settlement Upgrading and Critique of Existing Methodological Approaches. Habitat International, 26, 303-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(01)00049-2

- 2. COFOPRI (2011) Cofopri entregó 226,248 títulos de propiedad entre agosto Cofopri entregó 226,248 títulos de propiedad entre julio y agosto 2011. www.cofopri.gov.pe

- 3. De Soto, H. (1984). The Other Path. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc.

- 4. De Soto, H. (2000). The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York: Basic Books.

- 5. Fernandes, E. (2011). Regularization of Informal Settlements in Latin America, Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- 6. Gilbert, A. (2002). On the Mystery of Capital and the Myths of Hernando de Soto: What Difference Does Legal Title Make? International Development Planning Review, 26, 1-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.3828/idpr.24.1.1

- 7. Gouverneur, D. (2015). Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements: Shaping the Self-Constructed City. London: Routledge.

- 8. Hardoy, J., & Satterthwaite, D. (1989). Squatter Citizen. London: Earthscan.

- 9. Hermanson, J. (2016). Achieving Inclusiveness: The Challenge and Potential of Informal Settlements. http://citiscope.org/habitatIII/commentary/2016/01/achieving-inclusiveness-challenge-and-potential-informal-settlements

- 10. Huchzermeyer, M. (2004). Unlawful Occupation: Informal Settlements and Urban Policy in South Africa and Brazil. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

- 11. Imparato, I., & Ruster, J. (2003). Summary of Slum Upgrading and Participation: Lessons from Latin America. Washington DC: World Bank. http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-5370-5

- 12. King, W. (2003). Illegal Settlements and the Impact of Titling Programs. Heinonline, 44.

- 13. Lombard, M. (2014). Constructing Ordinary Places: Place-Making in Urban Informal Settlements in Mexico. Progress in Planning, 94, 1-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2013.05.003

- 14. Obeng-Odoom, F. (2013). The State of African Cities 2010: Governance, Inequality and Urban Land Markets. Cities, 31, 425-429. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.07.007

- 15. Obeng-Odoom, F. (2015). The Social, Spatial, and Economic Roots of Urban Inequality in Africa: Contextualizing Jane Jacobs and Henry George. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 74, 550-586. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12101

- 16. Okyere, A. S., & Kita, M. (2015). Rethinking Urban Informality and Informal Settlements: A Literature Discussion. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 17, 101-124.

- 17. Pugh, C. (1995). The Role of the World Bank in Housing. In B. Aldrich, & R. Sandhu (Eds.), Housing the Urban Poor: Policy and Practice in Developing Countries. London: Zed Books.

- 18. Riofrio, G. (2008). Peru: Los casos y sus lecciones. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- 19. Roy, A. (2005). Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71, 147-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976689

- 20. Roy, A. (2011). Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35, 223-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01051.x

- 21. Smolka, M., & Biderman, C. (2011). Housing Informality: An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Planning. In N. Brooks, K. Donaghy, & G. Jan Knaap (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Urban Economics and Planning. London: Oxford University Press.

- 22. Turner, J. (1968). Uncontrolled Urban Settlement: Problems and Policies. In G. Breese (Ed.), The City in Newly Developing Countries: Readings on Urbanism and Urbanization. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- 23. Turner, J., & Fichter, R. (Eds.) (1972). Freedom to Build: Dweller Control of the Housing Process. New York: Collier- Macmillan.

- 24. UN DESA (2015) Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainablecities

- 25. UN-Habitat (2006). The State of the World’s Cities Report 2006/2007: The Millennium Development Goals and Urban Sustainability. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- 26. Varley, A. (2013). Postcolonialising Informality? Environment and Planning D, 31, 4-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/d14410

- 27. Watson, V. (2009). The Planned City Sweeps the Poor away: Urban Planning and 21st Century Urbanization. Progress in Planning, 72, 151-193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2009.06.002

- 28. Wekesa, B. W., Steyna, G. S., & Otieno, F. A. O. (2011). A Review of Physical and Socio-Economic Characteristics and Intervention Approaches of Informal Settlements. Habitat International, 35, 238-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.09.006

NOTES

1The process of low-income settlements formation, where people first self-construct houses, then install services, were known in Peru as “barriadas” in the 1950s, “pueblos jóvenes” (young informal towns) in the 1970s, and since the 1990s as “asentamientos humanos” (human settlements).

2Conos refer to shantytowns located on the edges of Lima Metropolis, far from the urban core, where residents occupy marginal lands.

3The following account is based on interview with local community leaders from the field survey.

4ENACE was the institution in charge of the implementation of government housing solutions until 1998.

5Pircas is wall or floor construction height made up of uncut stones. Historically, it dates back to the Inca people.