Vol.3, No.5, 276-287 (2011) doi:10.4236/health.2011.35049 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Va riables associated with suicide ideation an d plans in a Japanese population Takuya Hasegaw a1*, Chiyoe Murata1, Tatsuya Noda1, Tomoko Takabayashi2, Takashi Ninomiya2, Shin ya Hayasaka1, Toshiyuki Ojima1 1Department of Community Health and Preventive Medicine, Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, Hamamatsu, Japan; *Corresponding Author: hasetaku07172000@gmail.com 2Hamamatsu City Mental Health and Welfare Center, Hamamatsu, Japan. Received 22 March 2011; revised 20 April 2011; accepted 26 April 2011. ABSTRACT The purpose of our study was to clarify vari- ables associated with suicide ideat ion and p lan s in a Japanese population. We conducted a ran- dom-sampling survey on mental health and sui- cide using a self-administered questionnaire for Hamamatsu City residents aged 15 - 79 years between May and June, 2008. This included questions about gender, age, outpatient treat- ment, alcohol problems, depression, living ar- rangements, marital status, annual family in- come, industry types as well as suicide ideation and plans. The correlation between these vari- ables and suicide ideation or plans was then analyzed with multiple logistic regression an aly- sis by gender. A total of 1051 responded to this questionnaire (response rate, 53.9%). Variables statistically associated with suicide ideation in males included alcohol problems, depression, lower annual family income, and accommoda- tions/eating/drinking services, while in females, the variables were younger age, outpatient treatment, depression, living alone, being single, being separated, lower annual family income, accommodations/eating/drinking services and unemployment. On the other hand, variables statistically associated with suicide plans in males were younger age, alcohol problems, de- pression, and lower annual family income, while in females they were younger age, alcohol problems, depression, being separated, lower annual family income, manufacturing, and ac- commodations/eating/drinking services. Except for industry types, variables associated with suicide ideation or plans were consistent with previous studies. The reason why workers en- gaging in manufacturing, or accommodations/ eating/drinking services were more likely to have suicide ideation or plans may be attributed to the structures and/or stresses unique to those industries. Keywords: Suicide Ideation; Suicide Plans; Variables 1. INTRODUCTION Suicide is a serious public health problem not only in Japan but also internationally. Every year, approximately one million people die of suicide; the suicide rate in the world is 16.0 per 100,000 as of 2000 [1]. In Japanese, it was less than 20.0 per year until 1997, but it increased drastically, exceeding 25.0 in 1998. Since then, it is re- portedly around 25.0 [2]. In light of this situation, “the Basic Act on Suicide Prevention” was approved in June in Japan, 2006, and “the General Policies of Compre- hensive Measures against Suicide” were formulated in June, 2007 to urge local governments to adopt measures for suicide prevention [2]. However, despite these meas- ures, the Japanese suicide rate has not decreased. In 2008, suicide was the seventh leading cause of death in Japan [3]. According to data from the World Health Or- ganization (WHO) in 2009, Japan has one of the world’s highest suicide rates [4]. Suicide involves multiple and interacting causes among genetic, psychological, marital, environmental, sociocul- tural and economical factors. Risk factors for completed suicide have been reported to involve males, older age, serotonin dysfunction, mental disorders such as depres- sion or schizophrenia, alcohol problems, drug abuse, low social class, poor employment status, low income, low education, separation as in those widowed or divorced, lack of social support or certain religious beliefs [5-13]. In addition, types of industries with a high suicide rate have been reported in agriculture/forestry, mining, con-  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 277277 struction, business/repair services, and transport/pro- duction [14-21]. Suicide-correlated behaviors include suicide ideation (thoughts of harming or killing oneself), suicide plans (specific plans to do so) and suicide at- tempts (non-fatal self-inflicted destructive acts with an explicit or implied intent to die). Though suicide-corre- lated behaviors do not necessarily end in completed sui- cide, it is regarded as an important precursor [22,23]. Because, as with schizophrenia, a stress-vulnerability model can be applied to the suicide process, the multiple factors mentioned above precede this process, whereas suicide plans are preceded by suicide ideation and the suicide acts in turn are preceded by suicide plans [24]. About 12% of those with suicide ideation attempted sui- cide [25]. Furthermore, they committed suicide attempts 6.09 times more frequently than those without suicide ideation [25]. Such attempts are one of the most impor- tant predictors of completed suicide, since 10% - 15% of those attempting suicide have reportedly gone through with it [26,27]. Several studies have mentioned risk factors for sui- cide-correlated behaviors, some of which reported that most of them were the same as the factors for completed suicide. For example, mental problems including de- pression or drug abuse, separation, poor employment status, low income or low education have been reported as risk factors for suicide-correlated behaviors [7,13, 28-35]. However, some factors such as gender or age have been reported to exert various effects on specific suicide-correlated behaviors. For example, such behav- iors are more common worldwide among females or the young, while completed suicide is more common among males and the elderly, though these tendencies do not necessarily apply to all countries or regions [36]. Some local governments have developed various measures for suicide prevention, one of which is to make appropriate intervention for those with suicide-correlated behaviors. Using a self-administered questionnaire, we conducted a random-sampling survey of suicide-corre- lated behaviors, particularly suicide ideation or plans, among Hamamatsu City residents. The aim of our study was to clarify risk factors associated with suicide idea- tion and plans in a Japanese population. 2. METHODS 2.1. Subjects We had to establish measures for a City-wide suicide preventive strategy. That was followed by the General Policies of Comprehensive Measures against Suicide. To grasp the actual situation of suicidality in Hamamatsu City, a cross-sectional investigation was conducted by the City. We cooperated in sampling the subjects and preparing the survey questionnaire, the data from which were used in our study. Between May and June, 2008, self-administered questionnaires were mailed to a sam- ple of 1950 Hamamatsu City residents aged 15 - 79 years, selected by stratified random sampling based on their gender, age and ward. Among them, a total of 1051 re- sponded (response rate, 53.9%). After excluding 142 subjects for incomplete data, the remaining 909 (401 males and 508 females) were analyzed. The study objec- tives were explained to the subjects via a form distrib- uted at the time of the survey; only subjects who agreed to participate in this survey responded. The survey data were anonymously collected by Hamamatsu City and kept confidential, making individual identification im- possible. 2.2. Measures 2.2.1. Suicide Ideation or Plans The relevant responses in this category were elicited by a questionnaire used in the Multisite Intervention Study on Suicidal Behavior (SUPRE-MISS) that WHO was conducted as part of a global suicide prevention program in eight countries [37]. The following question was used to assess suicide ideation: “Have you ever thought about committing suicide in the last twelve months?”, followed by two choices: “yes” or “no”. The following question was used to assess suicide plans: “Have you ever made plans for committing suicide?”, followed by two choices: “yes” or “no”. 2.2.2. Alcohol Problems Alcohol problems were assessed using a Japanese- translated CAGE (C, Cut down; A, Annoyed; G, Guilty; E, Eye-opener) questionnaire, followed by 2 choices: “yes” or “no” [38,39]. Those who responded in the af- firmative two or more times were considered positive (having alcohol problems). 2.2.3. Depression Depression was assessed with a Japanese-translated CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale), followed by 4 choices: “0”, “1”, “2” or “3” [40]. Those with a total of sixteen or more points were con- sidered positive (depressed). 2.2.4. Other Variables Furthermore, this questionnaire items included gender, age, outpatient treatment, living arrangements, marital status, annual family income and industry types. Age was categorized into 3 variables: “39 yrs or less,” “40 - 59 years,” or “60 years or more.” Outpatient treatment was denoted by a single item question “Do you receive  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 278 Table 1. Prevalence of suicide ideation and plans (N = 909). Males Females Variables N Suicide IdeationSuicide PlansN Suicide Ideation Suicide Plans Total 401 7.5 11.0 508 9.1 19.1 Age ≤ 39 133 9.0 17.3 188 12.2 25.0 40 - 59 141 8.5 9.2 193 9.8 21.2 60 ≤ 127 4.7 6.3 127 3.1 7.1 Outpatient Treatment No 229 7.0 11.8 280 5.7 19.6 Yes 172 8.1 9.9 228 13.2 18.4 Alcohol Problems Negative 337 6.2 9.8 487 8.6 17.5 Positive 64 14.1 17.2 21 19.0 57.1 Depression Negative 296 2.4 7.4 347 3.2 13.5 Positive 105 21.9 21.0 161 21.7 31.1 Living Arrangements Living with Someone Else 371 8.1 11.6 474 7.8 18.4 Living Alone 30 0.0 3.3 34 26.5 29.4 Marital Status Married 291 7.2 10.3 362 5.2 16.0 Single 92 8.7 13.0 100 17.0 22.0 Separated 18 5.6 11.1 46 21.7 37.0 Annual Family Income (Yen/Year) ≤ 1 999 999 29 17.2 13.8 39 25.6 25.6 2 000 000 - 6 999 999 231 7.4 12.1 282 5.3 17.0 7 000 000 ≤ 112 4.5 6.3 117 11.1 16.2 Unknown 29 10.3 17.2 70 11.4 28.6 Industry Types Construction 25 12.0 8.0 16 12.5 18.8 Manufacturing 113 6.2 11.5 65 9.2 33.8 Wholesale/Retail Trade 20 10.0 20.0 37 2.7 10.8 Accommodations/Eating/Drinking Services 3 66.7 33.3 20 20.0 35.0 Medical/Health Care and Welfare 8 0.0 12.5 55 9.1 23.6 Government 23 4.3 13.0 11 18.2 27.3 Other Services 38 7.9 5.3 42 9.5 26.2 Others 78 3.8 7.7 51 9.8 15.7 Housewife/Househusband 1 0.0 0.0 132 3.8 10.6 Student 19 21.1 15.8 31 9.7 16.1 Unemployment 73 6.8 12.3 48 18.8 14.6  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 279279 treatment at a hospital, clinic, or acupuncture/acupres- sure clinic due to disease?”, followed by two choices: “yes” or “no”. Living arrangements were categorized into 2 variables: “living with someone else” or “living alone”. Marital status was categorized into 3 variables: “married”, “single” or “separated (widow/widower or divorced)”. Annual family income in yen was catego- rized into 4 variables: “1,999,999 or less”, “2,000,000 to 6,999,999”, “7,000,000 or more” or “unknown”. Indus- try types were categorized into the following 20 vari- ables: “agriculture/forestry,” “fisheries,” “mining and quarrying of stone and gravel”, “construction”, “manu- facturing”, “electricity/gas/heat supply/ water”, “infor- mation/communications”, “transport/postal activities”, “wholesale/retail trade”, “finance/insurance”, “real es- tate/rental and leasing goods”, “accommodations/ eat- ing/drinking services”, “medical/health care and wel- fare”, “education/learning support”, “government”, “other services”, “other”, “housewife/househusband”, “student” or “unemployment”. At analysis, because the total num- ber of male or female subjects were 15 or less, the fol- lowing industries were included in “others”; “agricul- ture/forestry”, “fisheries”, “mining and quarrying of stone and gravel”, “electricity/gas/heat supply/water”, “information/communications”, “transport/postal activi- ties”, “finance/insurance”, “real estate/rental and leasing goods”, “education/learning support” and “other”. 2.3. Data Analysis Descriptive epidemiological statistics were used to compute the number and percentage of subjects with suicide ideation or plans by each variable. The correla- tion between each variable and suicide ideation or plans was analyzed with logistic regression models by gender after adjustments only for age in years (Model 1), and age in years with outpatient treatment, alcohol problems, depression, living arrangements, marital status, annual family income and industry types (Model 2). Odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and P value were calculated. Used as reference groups were subjects aged 60 years or more with no outpatient treatment, no alcohol problems, no depression, lived with someone else, were married, engaged in wholesale/retail trade, or whose annual family income was 7,000,000 or more. P values of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically sig- nificant. All statistical calculations were performed with SPSS for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). 3. RESULTS Table 1 shows the descriptive epidemiological char- acteristics of our study subjects with suicide ideation or plans. Among them, 8.4% (7.5% of males and 9.1% of females) or 15.5% (11.0% of males and 19.1% of fe- males) had suicide ideation or plans, respectively. The younger both males and females were, the more likely they were to have suicide ideation or plans. Females who had outpatient treatment were more likely to have sui- cide ideation than those who did not. Both males and females with alcohol problems were more likely to have suicide ideation or plans than those without such prob- lems. Depression showed the same tendency. A lower percentage of males who were living alone had suicide ideation or plans than those living with someone else, though a higher percentage of females living alone had suicide ideation or plans than those living with someone else. Females who were separated were more likely to have suicide ideation or plans. The lower the income males had, the more they were likely to have suicide ideation or plans while the lower the income females had, the more they were likely to only have suicide plans. Among industry types, both males and females engaging in accommodations/eating/drinking services showed the highest percentage of suicide ideators or planners. Re- garding gender difference, there was no statistical dif- ference in suicide ideation (Model 1, OR: 1.18, 95% CI: 0.73 - 1.91, Model 2, OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.54 - 1.83), though statistically more females than males had suicide plans (Model 1, OR: 1.83, 95% CI: 1.24 - 2.69, Model 2, OR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.36 - 3.46) (data not shown). Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analy- sis for variables associated with suicide ideation in males. Statistically significant variables associated with suicide ideation in both Models were depression and an annual family income of 1,999,999 or less. Alcohol problems and accommodations/eating/drinking services showed statistical significance only in Model 1. Table 3 shows the results of logistic regression analy- sis for variables associated with suicide ideation in fe- males. Statistically significant variables associated with suicide ideation in both Models were 39 yrs or less, 40 - 59 yrs, outpatient treatment, depression and being sepa- rated. Statistically significant variables associated with suicide ideation only in Model 1 were living alone, being single, an annual family income of 1,999,999 or less, accommodations/eating/drinking services and unemploy- ment. Table 4 shows the results of logistic regression analy- sis for variables associated with suicide plans in males. Statistically significant variables associated with suicide plans in both Models were 39 years or less, alcohol problems and depression. A statistically significant vari- able associated with suicide plans only in Model 1 was an annual family income of 1,999,999 or less. Table 5 shows the results of logistic regression analy- sis for variables associated wi h suicide plans in females. t  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 280 Table 2. Logistic regression analysis for variables associated with suicide ideation in males (N = 401). Variables Model 1 P value OR(95%CI)*Model 2 P value Age ≤ 39 2.00 (0.73 - 5.50) 0.179 3.16 (0.57 - 17.55) 0.187 40 - 59 1.88 (0.68 - 5.16) 0.223 2.77 (0.62 - 12.30) 0.180 60 ≤ 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Outpatient Treatment No 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Yes 1.54 (0.69-3.40) 0.291 1.50 (0.57-3.96) 0.416 Alcohol Problems Negative 1 (reference) 1(reference) Positive 2.62 (1.13 - 6.08) 0.025 2.79 (0.93 - 8.39) 0.067 Depression Negative 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Positive 11.39 (4.70 - 27.62) < 0.001 11.54 (4.31 - 30.92) < 0.001 Living Arrangements Living with Someone else 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Living Alone −** −** Marital Status Married 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Single 0.97 (0.36 - 2.59) 0.948 0.69 (0.15 - 3.08) 0.624 Separated 0.76 (0.10 - 6.00) 0.790 2.44 (0.19 - 31.39) 0.495 Annual Family Income (Yen/year) ≤ 1 999 999 8.22 (1.94 - 34.95) 0.004 6.56 (1.02 - 42.17) 0.047 2 000 000 - 6 999 999 1.92 (0.68 - 5.40) 0.216 1.08 (0.31 - 3.75) 0.908 7 000 000 ≤ 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Unknown 2.21 (0.47 - 10.40) 0.317 1.37 (0.21 - 9.01) 0.741 Industry Types Construction 1.31 (0.19 - 8.86) 0.781 1.40 (0.14 - 13.90) 0.774 Manufacturing 0.60 (0.11 - 3.14) 0.544 0.84 (0.11 - 6.32) 0.865 Wholesale/Retail Trade 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Accommodations/Eating/Drinking Services 20.82 (1.15 - 375.73)0.040 19.65 (0.84 - 461.06) 0.064 Medical/Health Care and Welfare −** −** Government 0.40 (0.03 - 4.89) 0.475 0.78 (0.05 - 13.24) 0.863 Other Services 0.78 (0.12 - 5.14) 0.797 0.92 (0.10 - 8.72) 0.945 Others 0.39 (0.06 - 2.55) 0.327 0.45 (0.05 - 4.22) 0.487 Housewife/Househusband −** −** Student 2.30 (0.35 - 15.14) 0.387 3.64 (0.28 - 47.49) 0.324 Unemployment 1.03 (0.16 - 6.53) 0.973 0.63 (0.06 - 6.93) 0.704 Model 1: Adjusted for age in years; Model 2: Adjusted for age in years, outpatient treatment, alcohol problems, depression, living arrangements, marital status, annual family income and industry types; *OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; **There were no such subjects.  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 281281 Table 3. Logistic regression analysis for variables associated with suicide ideation in females (N = 508). Variables Model 1 P value OR(95%CI)*Model 2 P value Age ≤ 39 4.29 (1.45 - 12.71) 0.009 12.31 (2.45 - 61.81) 0.002 40 - 59 3.36 (1.12 - 10.11) 0.031 10.01 (2.28 - 43.86) 0.002 60 ≤ 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Outpatient Treatment No 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Yes 3.44 (1.78 - 6.65) < 0.001 2.62 (1.21 - 5.67) 0.014 Alcohol problems Negative 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Positive 2.05 (0.66 - 6.44) 0.217 0.77 (0.18 - 3.33) 0.722 Depression Negative 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Positive 8.51 (4.13 - 17.55) < 0.001 6.38 (2.85 - 14.28) < 0.001 Living Arrangements Living with Someone else 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Living Alone 4.48 (1.91 - 10.52) 0.001 1.22 (0.36 - 4.19) 0.752 Marital Status Married 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Single 2.94 (1.30 - 6.64) 0.009 2.39 (0.79 - 7.26) 0.124 Separated 6.95 (2.83 - 17.03) < 0.001 3.56 (1.03 - 12.25) 0.045 Annual family income (Yen/year) ≤ 1 999 999 4.23 (1.59 - 11.28) 0.004 1.50 (0.40 - 5.59) 0.545 2 000 000 - 6 999 999 0.54 (0.24 - 1.18) 0.122 0.42 (0.17 - 1.05) 0.064 7 000 000 ≤ 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Unknown 0.88 (0.33 - 2.38) 0.807 0.34 (0.10 - 1.15) 0.082 Industry Types Construction 4.58 (0.38 - 55.30) 0.231 3.07 (0.22 - 43.55) 0.408 Manufacturing 3.48 (0.40 - 30.72) 0.261 2.37 (0.24 - 23.43) 0.462 Wholesale/Retail Trade 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Accommodations/Eating/Drinking Services 10.26 (1.04 - 101.47)0.046 4.74 (0.40 - 56.55) 0.218 Medical/Health Care and Welfare 3.10 (0.35 - 27.94) 0.312 1.60 (0.15 - 16.71) 0.696 Government 6.25 (0.50 - 77.50) 0.154 2.31 (0.16 - 33.46) 0.539 Other Services 3.50 (0.37 - 33.11) 0.274 2.42 (0.22 - 26.70) 0.470 Others 3.99 (0.44 - 36.12) 0.218 3.12 (0.30 - 31.96) 0.339 Housewife/Househusband 1.52 (0.17 - 13.58) 0.708 2.42 (0.24 - 24.66) 0.458 Student 2.65 (0.25 - 28.31) 0.420 0.96 (0.08 - 11.94) 0.973 Unemployment 15.76 (1.80 - 138.36)0.013 7.58 (0.73 - 78.66) 0.090 Model 1: Adjusted for age in years; Model 2: Adjusted for age in years, outpatient treatment, alcohol problems, depression, living arrangements, marital status, nnual family income and industry types; *OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. a  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 282 Statistically significant variables associated with suicide plans in both Models were 39 years or less, 40 - 59 years, alcohol problems, depression, being separated, and manufacturing. Statistically significant variables associ- ated with suicide plans only in Model 1 were an annual family income of 1,999,999 or less and accommoda- tions/eating/drinking services. 4. DISCUSSION To the best of knowledge, this study is the first to in- vestigate the factors associated with suicide ideation and plans in a Japanese population after consideration of multiple factors. The response rate in this study was 53.9%. This was almost the same rate as in the previous Japanese study (response rate, 58.4%) [41]. The present study showed that the prevalence of suicide ideation and plans was 8.4 and 15.5%, respectively. Bertolote et al. reported that with the SUPRE-MISS protocol the prevalence of sui- cide-correlated behaviors varied widely among different countries [37]. They reported that the prevalence of sui- cide ideation and plans in a general population was 2.6% - 25.4% and 1.1% - 15.6%, respectively [37]. In contrast, Scocco et al. reported that the prevalence of suicide ideation and plans in an Italian population was 3.0% and 0.7%, respectively [13]. In Japanese studies, Ono et al. reported that the prevalence of suicide ideation and plans in Japan was 10.9% and 2.1%, respectively [41]. The prevalence of suicide plans in our study was higher than in previous studies. In general, the prevalence of suicide ideation was higher than that of suicide plans, whereas our study showed that the prevalence of suicide ideation was lower. The possible reason for that discrepancy may be that subjects were supposed to first answer a question about suicide ideation in the last twelve months, followed by a question about lifetime suicide plans in our study, sug- gesting that there might be some subjects who misun- derstood the second question as one about lifetime sui- cide ideation. The questionnaire used in the SUPRE- MISS protocol included several questions about lifetime suicide ideation or plans, the first time he or she seri- ously entertained suicide ideation or plans, suicide idea- tion or plans in the last twelve months, and the last time when he or she seriously considered suicide ideation or plans; all of them were supposed to be asked in the order above. In addition, in the studies mentioned above, sub- jects were directly interviewed, but not asked to respond to a self-administered questionnaire, and responses in regard to suicide ideation or plans differed slightly from our questions. Thus, it may not be appropriate to com- pare our study to their protocol, though the prevalence of suicide ideation in our study was generally consistent with that in previous studies. Though there was no statistical gender difference with suicide ideation in our study, females were more likely to have made suicide plans than males. Most studies reported that the prevalence of suicide ideation in fe- males was higher than in males, though that might vary by countries or regions [36]. Scocco et al. reported that in Italy the prevalence of suicide plans among females was higher than in males [13]. In Japanese studies, Ono et al. found no gender difference in the prevalence of suicide ideation or plans [41]. This discrepancy may be due to the difference of subjects and investigation year between our study and previous studies. The factors associated with suicide ideation were al- cohol problems, depression and lower annual family income in males, and younger age, outpatient treatment, depression, living alone, being single, being separated and lower annual family income in females. These re- sults are consistent with those in previous studies show- ing risk factors associated with suicide ideation [13,29, 30,32-35,41-43]. Variables associated with suicide plans showed the same tendency. Although few studies men- tioned risk factors associated with suicide plans, Scocco et al. reported that in an Italian population risk factors associated with suicide plans were female, alcohol prob- lems and depression, and that the younger the subjects were, the more likely they were to have suicide plans, though not statistically significant [13]. Suicide and sui- cide-correlated behaviors are mainly brought out by de- pression. Depression results from multiple factors in- cluding biological, psychosocial and existential, eco- nomical, and marital factors. Alcohol problems, lower income, having diseases, loneliness from such as living alone, being single or being separated are main causes of depression, bringing out suicidal thoughts. Since work is one of the most important human activi- ties, it has a major impact on human suicidality. Numer- ous studies have mentioned the correlation between oc- cupation or industry and completed suicide [14-21, 44-61]. Thus, suicide-correlated behaviors may be re- lated to them. In our study, industry types statistically associated with suicide ideation were accommodations/ eating/drinking services in males, and accommodations/ eating/drinking services and unemployment in females. On the other hand, while there were no industry types statistically associated with suicide plans in males, manufacturing and accommodations/eating/drinking services were associated with suicide plans in females. Only a few studies have addressed the correlation between unemployment and suicide ideation [31,33]. However, to our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the correlation between industry types and suicide-correlated behaviors. The reasons why orkers engaged in manu- w  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 283283 Table 4. Logistic regression analysis for variables associated with suicide plans in males (N = 401). Variables Model 1 P Value OR (95%CI)*Model 2 P Value Age ≤ 39 3.11 (1.34 - 7.24) 0.009 6.19 (1.77 - 21.63) 0.004 40 - 59 1.51 (0.61 - 3.77) 0.377 2.38 (0.75 - 7.49) 0.139 60 ≤ 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Outpatient Treatment No 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Yes 1.12 (0.56 - 2.24) 0.745 1.01 (0.48 - 2.14) 0.976 Alcohol Problems Negative 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Positive 2.19 (1.02 - 4.68) 0.044 2.67 (1.11 - 6.46) 0.029 Depression Negative 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Positive 3.06 (1.60 - 5.85) 0.001 2.98 (1.47 - 6.00) 0.002 Living Arrangements Living with Someone Else 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Living Alone 0.23 (0.03 - 1.78) 0.160 0.20 (0.02 - 1.83) 0.156 Marital Status Married 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Single 0.70 (0.31 - 1.58) 0.387 0.78 (0.28 - 2.22) 0.648 Separated 1.21 (0.26 - 5.65) 0.806 2.47 (0.39 - 15.61) 0.338 Annual Family Income (Yen/Year) ≤ 1 999 999 4.21 (1.04 - 17.06) 0.044 2.64 (0.55 - 12.73) 0.227 2 000 000 - 6 999 999 2.21 (0.92 - 5.30) 0.075 1.85 (0.73 - 4.72) 0.197 7 000 000 ≤ 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Unknown 2.17 (0.61 - 7.71) 0.233 1.83 (0.44 - 7.59) 0.408 Industry Types Construction 0.44 (0.07 - 2.80) 0.386 0.41 (0.06 - 2.94) 0.372 Manufacturing 0.59 (0.17 - 2.08) 0.409 0.82 (0.19 - 3.45) 0.782 Wholesale/Retail Trade 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Accommodations/Eating/Drinking Services 3.82 (0.25 - 57.84) 0.334 3.43 (0.20 - 58.52) 0.395 Medical/Health Care and Welfare 0.75 (0.07 - 8.40) 0.816 1.53 (0.12 - 19.66) 0.746 Government 0.79 (0.15 - 4.22) 0.779 1.17 (0.18 - 7.65) 0.873 Other Services 0.23 (0.04 - 1.43) 0.116 0.26 (0.04 - 1.85) 0.178 Others 0.40 (0.10 - 1.62) 0.199 0.48 (0.10 - 2.27) 0.358 Housewife/Househusband −** −** Student 0.48 (0.09 - 2.60) 0.397 0.77 (0.10 - 5.80) 0.802 Unemployment 1.30 (0.31 - 5.51) 0.721 1.50 (0.27 - 8.23) 0.641 Model 1: Adjusted for age in years; Model 2: Adjusted for age in years, outpatient treatment, alcohol problems, depression, living arrangements, marital status, annual family income and industry types; *OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; **There were no such subjects.  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 284 Table 5. Logistic regression analysis for variables associated with suicide plans in females (N = 508). Variables Model 1 P value OR(95%CI)*Model 2 P Value Age ≤ 39 4.37 (2.06 - 9.29) < 0.001 5.89 (2.26 - 15.31) < 0.001 40 - 59 3.54 (1.65 - 7.57) 0.001 4.60 (1.90 - 11.16) 0.001 60 ≤ 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Outpatient Treatment No 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Yes 1.20 (0.75 - 1.91) 0.453 1.01 (0.60 - 1.72) 0.963 Alcohol Problems Negative 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Positive 5.24 (2.12 - 12.97) < 0.001 5.07 (1.74 - 14.83) 0.003 Depression Negative 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Positive 2.79 (1.75 - 4.46) <0.001 2.35 (1.39 - 3.99) 0.002 Living Arrangements Living with Someone else 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Living Alone 1.93 (0.87 - 4.27) 0.105 0.79 (0.27 - 2.33) 0.673 Marital Status Married 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Single 0.91 (0.49 - 1.69) 0.767 0.64 (0.29 - 1.44) 0.282 Separated 4.96 (2.35 - 10.47) < 0.001 3.74 (1.47 - 9.56) 0.006 Annual Family Income (Yen/Year) ≤ 1 999 999 2.67 (1.07 - 6.64) 0.035 1.55 (0.51 - 4.74) 0.442 2 000 000 - 6 999 999 1.32 (0.73 - 2.40) 0.357 1.40 (0.72 - 2.73) 0.316 7 000 000 ≤ 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Unknown 1.99 (0.93 - 4.24) 0.075 1.92 (0.80 - 4.63) 0.144 Industry types Construction 1.70 (0.33 - 8.81) 0.527 0.98 (0.15 - 6.38) 0.986 Manufacturing 4.17 (1.28 - 13.61) 0.018 4.92 (1.33 - 18.15) 0.017 Wholesale/Retail Trade 1 (reference) 1 (reference) Accommodations/Eating/Drinking Services 5.08 (1.23 - 20.98) 0.025 3.17 (0.65 - 15.50) 0.154 Medical/Health Care and Welfare 2.23 (0.66 - 7.57) 0.197 3.04 (0.79 - 11.61) 0.105 Government 2.45 (0.45 - 13.33) 0.300 1.89 (0.31 - 11.34) 0.488 Other Services 2.75 (0.78 - 9.67) 0.115 3.30 (0.82 - 13.20) 0.092 Others 1.55 (0.42 - 5.68) 0.509 1.90 (0.46 - 7.79) 0.375 Housewife/Househusband 1.04 (0.32 - 3.42) 0.952 1.32 (0.35 - 4.94) 0.678 Student 1.10 (0.26 - 4.75) 0.897 1.28 (0.25 - 6.48) 0.767 Unemployment 2.23 (0.57 - 8.69) 0.247 1.60 (0.35 - 7.38) 0.545 Model 1: Adjusted for age in years; Model 2: Adjusted for age in years, outpatient treatment, alcohol problems, depression, living arrangements, marital status, nnual family income and industry types; *OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. a  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 285285 facturing or accommodations/eating/drinking services were that they were more likely to have suicidal ideation or plans due to the structures and/or physical and mental stresses specific to such industries. The major stressors on manufacturing workers are reported to be offensive physical, chemical and ergonomic factors in the working environment, low job control, high job demands, bur- densome patterns such as shift work, unstable working hours and overtime work, income pay inadequate for hours worked, sudden changes in work schedules, few opportunities to develop their abilities and techniques, monotonous operations, role ambiguity, lack of social support from their boss or colleagues, unstable status such as irregular employment, restructuring, sudden transfer or relocation, and few opportunities to partici- pate in their companies’ administration and management [62]. On the other hand, stressors on workers in accom- modations/eating/drinking services are also reported to be various work patterns, shift work, low income, hard and long working hours, long standing time, exposure to unpleasant food odors, and increased opportunities to reward for various demands from customers with dif- ferent values [63]. These stresses may be related to de- pression, bringing out suicidal thoughts. Openly accessible at Several limitations should be considered when inter- preting these results. First, a cross-sectional design used in our study does not necessarily demonstrate that the variables associated with suicide ideation or plans are causal factors. Second, a small sample size calls for cau- tious interpretation of the results, since a type 2 error cannot be excluded. Third, this questionnaire does not include the onset age of suicide ideation or plans and time since the onset of suicide ideation or plans. Fourth, our study did not assess several important mental condi- tions such as schizophrenia or borderline personality disorder because it proved very difficult to judge these diseases only from a self-administered questionnaire. Despite these limitations, our study shed light on multi- ple risk factors associated with suicide ideation/plans among a Japanese population. In conclusion, alcohol problems, depression, inade- quate annual family income and accommodations/eating/ drinking services in males, and younger age, outpatient treatment, depression, living alone, being single, being separated, insufficient annual family income, accommo- dations/eating/drinking services and unemployment in females may be factors statistically associated with sui- cide ideation. On the other hand, younger age, alcohol problems, depression and inadequate annual family in- come in males, and younger age, alcohol problems, de- pression, being separated, lower annual family income, manufacturing and accommodations/eating/drinking ser- vices in females may be factors associated with suicide plans. It is important to consider these factors in devel- oping anti-suicidal measures to prevent suicide ideation or plans from escalating into suicidal attempts or com- pletions. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to all the participants in our study. REFERENCES [1] World Health Organization (2009) Suicide prevention (SUPRE). http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/sui cideprevent/en/ [2] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Japan (2009) Section 4, promotion of preventive measures against sui- cide. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw2/part2/p2c9s4 .pdf#search=Promotion of Preventive Measures against Suicide [3] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Japan (2008) Vital statistics FY2008. [4] World Health Organization (2009) Suicide rates per 100,000 by country, year and sex. http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide_rat es/en/ [5] Cantor, C.H., Slater, P.J. and Najman, J.M. (1995) So- cioeconomic indices and suicide rate in Queensland. Australian Journal of Public Health, 19, 417-420. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.1995.tb00397.x [6] Gravseth, H.M., Mehlum, L., Bjerkedal, T. and Kris- tensen, P. (2010) Suicide in young Norwegians in a life course perspective: Population based cohort study. Jour- nal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 64, 407-412. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.083485 [7] Harris, E.C. and Barraclough, B. (1997) Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 205-228. doi:10.1192/bjp.170.3.205 [8] Hawton, K. and Heeringen, van K. (2009) Suicide. Lan- cet, 373, 1372-1381. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X [9] Luoma, J.B. and Pearson, J.L. (2002) Suicide and marital status in the United States, 1991-1996: Is widowhood a risk factor? American Journal of Public Health, 92, 1518-1522. doi:10.2105/AJPH.92.9.1518 [10] Moscicki, E.K. (1989) Identification of suicide risk fac- tor using epidemiological studies. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 79, 490-497. [11] Rockville (2001) National strategy for suicide prevention: Goals and objectives for action. Center for Mental Health Services. [12] Smith, J.C., Mercy, J.A. and Conn, J.M. (1988) Marital status and the risk of suicide. American Journal of Public Health, 78, 78-80. doi:10.2105/AJPH.78.1.78 [13] Scocco, P., Girolamo, de G., Vilagut, G. and Alonso, J. (2008) Prevalence of suicide ideation, plans, and at- tempts and related risk factors in Italy: Results from the  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 286 European study on the epidemiology of mental disor- ders-world mental health study. Comprehensive Psychia- try, 49, 13-21. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.004 [14] Burnley, I.H. (1995) Socioeconomic and spatial differen- tials in mortality and means of committing suicide in New South Wales, Australia, 1985-1991. Social Science & Medicine, 41, 687-698. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)00378-7 [15] Hawton, K., Fagg, J., Simkin, S., Harriss, L. and Malm- berg, A. (1998) Methods used for suicide by farmers in England and Wales: The contribution of availability and its relevance to prevention. British Journal of Psychiatry, 173, 320-324. doi:10.1192/bjp.173.4.320 [16] Hawton, K., Fagg, J., Simkin, S., Harriss, L., Malmberg, A. and Smith, D. (1999) The geographical distribution of suicides in farmers in England and Wales. Social Psy- chiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34, 122-127. doi:10.1007/s001270050122 [17] Kposowa, A.J. (1999) Suicide mortality in the United States: Differentials by industrial and occupational groups. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 36, 645-652. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199912)36:6<645::AID-A JIM7>3.0.CO;2-T [18] Liu, T. and Waterbor, J.W. (1994) Comparison of suicide rates among industrial groups. American Journal of In- dustrial Medicine, 25, 197-203. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700250206 [19] Malmberg, A., Simkin, S. and Hawton, K. (1999) Suicide in farmers. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 103-105. doi:10.1192/bjp.175.2.103 [20] Meltzer, H., Griffiths, C., Brock, A., Rooney, C. and Jenkins, R. (2008) Patterns of suicide by occupation in England and Wales, 2001-2005. British Journal of Psy- chiatry, 193, 73-76. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040550 [21] Notkola, V.J., Martikainen, P. and Leino, P.I. (1993) Time trends in mortality in forestry and construction workers in Finland 1970-1985 and impact of adjustment for so- cioeconomic variables. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 47, 186-191. doi:10.1136/jech.47.3.186 [22] Paykel, E.S., Myers, J.K., Lindenthal, J.J. and Tanner, J. (1974) Suicidal feelings in the general population: A prevalence study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 124, 460-469. doi:10.1192/bjp.124.5.460 [23] Zubin, J. (1974) Observations on nosological issues in the classification of suicidal behavior. In: A. Beck, et al., Eds, the Prediction of Suicide, Charles Press Publishers, Bowie, pp. 3-25. [24] Wasserman, D., Sokolowski, M., Wasserman, J. and Ru- jescu, D. (2009) Neurobiology and the genetics of sui- cide; Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide preven- tion. Oxford University Press, New York. [25] Pirkis, J., Burgess, P. and Dunt, D. (2000) Suicidal idea- tion and suicide attempts among Australian adults. Crisis, 21, 16-25. doi:10.1027//0227-5910.21.1.16 [26] Owens, D., Horrocks, J. and House, A. (2002) Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 193-199. doi:10.1192/bjp.181.3.193 [27] Suominen, K., Isometsa, E., Suokas, J., Haukka, J., Achte, K. and Lonnqvist, J. (2004) Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: A 37-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 562-563. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.562 [28] Beautrais, A.L., Joyce, P.R., Mulder, R.T., Fergusson, D.M., Deavoll, B.J. and Nightingale, S.K. (1996) Preva- lence and comorbidity of mental disorders in persons making serious suicide attempts: A case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 1009-1014. [29] Bernal, M., Haro, J.M., Bernert, S., Brugha, T., Graaf, de R., Bruffaerts, R., et al. (2007) Risk factors for suicidal- ity in Europe: Results from the ESEMED study. Journal of Affect ive Disorders, 101, 27-34. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.018 [30] Dennis, M., Baillon, S., Brugha, T., Lindesay, J., Stewart, R. and Meltzer, H. (2007) The spectrum of suicidal idea- tion in Great Britain: Comparisons across a 16 - 74 years age range. Psychological Medicine, 37, 795-805. doi:10.1017/S0033291707000013 [31] Fergusson, D.M., Boden, J.M. and Horwood, L.J. (2007) Unemployment and suicidal behavior in a New Zealand birth cohort: A fixed effects regression analysis. Crisis, 28, 95-101. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.28.2.95 [32] Kalist, D.E., Molinari, N.A. and Siahaan, F. (2007) In- come, employment and suicidal behavior. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 10, 177-187. [33] Kjoller, M. and Helweg-Larsen, M. (2000) Suicidal idea- tion and suicide attempts among adult Danes. Scandina- vian Journal of Publi c Heal t h, 28 , 54-61. [34] Weissman, M.M., Bland, R.C., Canino, G.J., Greenwald, S., Hwu, H.G., Joyce, P.R., et al. (1999) Prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychological Medicine, 29, 9-17. doi:10.1017/S0033291798007867 [35] Yen, Y.C., Yang, M.J., Yang, M.S., Lung, F.W., Shih, C.H., Hahn, C.Y., et al. (2005) Suicidal ideation and as- sociated factors among community-dwelling elders in Taiwan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 59, 365-371. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01387.x [36] Kessler, R.C., Borges, G. and Walters, E.E. (1999) Preva- lence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 617-626. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617 [37] Bertolote, J.M., Fleischmann, A., Leo, de D., Bolhari, J., Botega, N., Silva, de D., et al. (2005) Suicide attempts, plans, and ideation in culturally diverse sites: The WHO SUPRE-MISS community survey. Psychological Medi- cine, 35, 1457-1465. doi:10.1017/S0033291705005404 [38] Aertgeerts, B., Buntinx, F. and Kester, A. (2004) The value of the CAGE in screening for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in general clinical populations: A diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiol- ogy, 57, 30-39. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00254-3 [39] Ewing, J.A. (1984) Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. Journal of American Medical Association, 252, 1905-1907. doi:10.1001/jama.252.14.1905 [40] Andresen, E.M., Malmgren, J.A., Carter, W.B. and Pat- rick, D.L. (1994) Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10, 77-84. [41] Ono, Y., Kawakami, N., Nakane, Y., Nakamura, Y.,  T. Hasegawa et al. / Health 3 (2011) 276-287 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 287287 Tachimori, H., Iwata, N., et al. (2008) Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide-related outcomes in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62, 442-449. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01823.x [42] Druss, B. and Pincus, H. (2000) Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in general medical illnesses. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160, 1522-1526. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.10.1522 [43] Stravynski, A. and Boyer, R. (2001) Loneliness in rela- tion to suicide ideation and parasuicide: A popula- tion-wide study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31, 32-40. doi:10.1521/suli.31.1.32.21312 [44] Agerbo, E., Gunnell, D., Bonde, J.P., Mortensen, P.B. and Nordentoft, M. (2007) Suicide and occupation: The im- pact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1131-1140. doi:10.1017/S0033291707000487 [45] Alexander, R.E. (2001) Stress-related suicide by dentists and other health care workers: Fact or folklore? Journal of the American Dental Association , 132, 786-794. [46] Dubrow, R. (1988) Suicide among social workers in Rhode Island. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 30, 211-213. [47] Hamermesh, D.S. and Soss, N.M. (1974) An economic theory of suicide. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 83-98. doi:10.1086/260171 [48] Hawton, K., Simkin, S., Rue, J., Haw, C., Barbour, F., Clements, A., et al. (2002) Suicide in female nurses in England and Wales. Psychological Medicine, 32, 239- 250. doi:10.1017/S0033291701005165 [49] Hawton, K., Malmberg, A. and Simkin, S. (2004) Suicide in doctors: A psychological autopsy study. Journal of Psychosomatic Rese a rch, 57, 1-4. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00372-6 [50] Hawton, K. and Vislisel, L. (1999) Suicide in nurses. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 86-95. [51] Hem, E., Berg, A.M. and Ekeberg, A.O. (2001) Suicide in police—A critical review. Suicide and Life-Threat- ening Behavior , 31, 224-233. doi:10.1521/suli.31.2.224.21513 [52] Kelly, S. and Bunting, J. (1998) Trends in suicide in Eng- land and Wales, 1982-1996. Population Trends, 92, 29-41. [53] Mellanby, R.J. (2005) Incidence of suicide in the veteri- nary profession in England and Wales. Veterinary Record, 157, 415-417. [54] Preti, A., Biasi, de F. and Miotto, P. (2001) Musical crea- tivity and suicide. Psychological Reports, 89, 719-727. doi:10.2466/PR0.89.7.719-727 [55] Richings, J.C., Khara, G.S. and McDowell, M. (1986) Suicide in young doctors. British Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 475-478. doi:10.1192/bjp.149.4.475 [56] Schernhammer, E.S. and Colditz, G.A. (2004) Suicide rates among physicians: A quantitative and gender as- sessment (meta-analysis). American Journal of Psychia- try, 161, 2295-2302. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295 [57] Schwartz, E. (1987) Proportionate mortality ratio analy- sis of automobile mechanics and gasoline service station workers in New Hampshire. American Journal of Indus- trial Medicine, 12, 91-99. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700120110 [58] Seagroatt, V. and Rooney, C. (1993) Suicide in doctors. BMJ, 307, 447. doi:10.1136/bmj.307.6901.447 [59] Stack, S. (2001) Occupation and suicide. Social Science Quarterly, 82, 384-397. doi:10.1111/0038-4941.00030 [60] Stack, S. (1996) Gender and suicide risk among artists: A multivariate analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Be- havior, 26, 374-379. [61] Stark, C., Belbin, A., Hopkins, P., Gibbs, D., Hay, A. and Gunnell, D. (2006) Male suicide and occupation in Scot- land. Health Statistics Quarterly, 29, 26-29. [62] Watanabe, M. (2003) Stress management in manufactur- ing industries. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi, 45, 1-6. doi:10.1539/sangyoeisei.45.1 [63] Suka, T. and Shoji, M. (2007) An attempt to construct an emotional labor behavior scale for restaurant workers. Japanese Association of Industrial/Organizational Psy- chology, 20, 41-52.

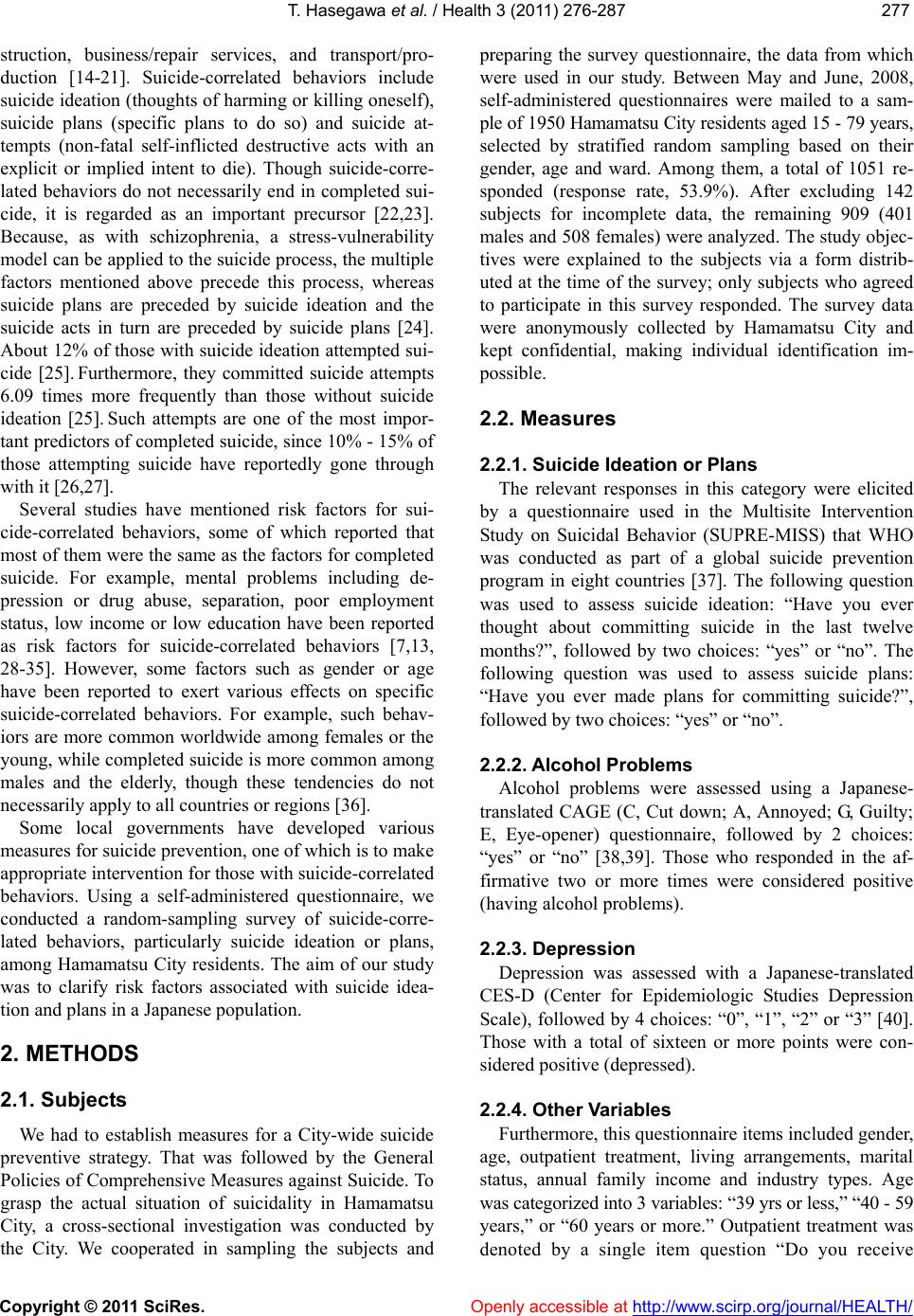

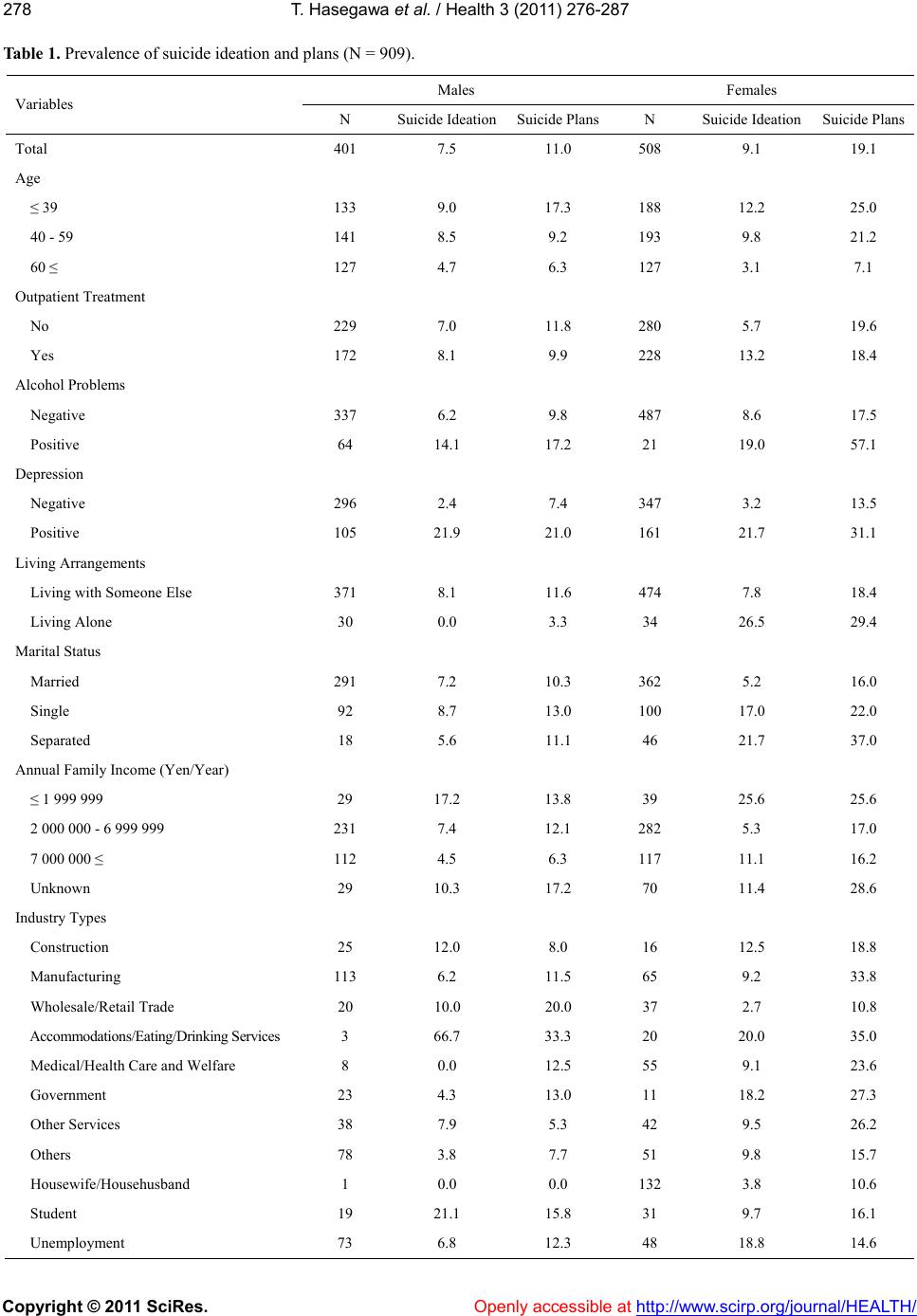

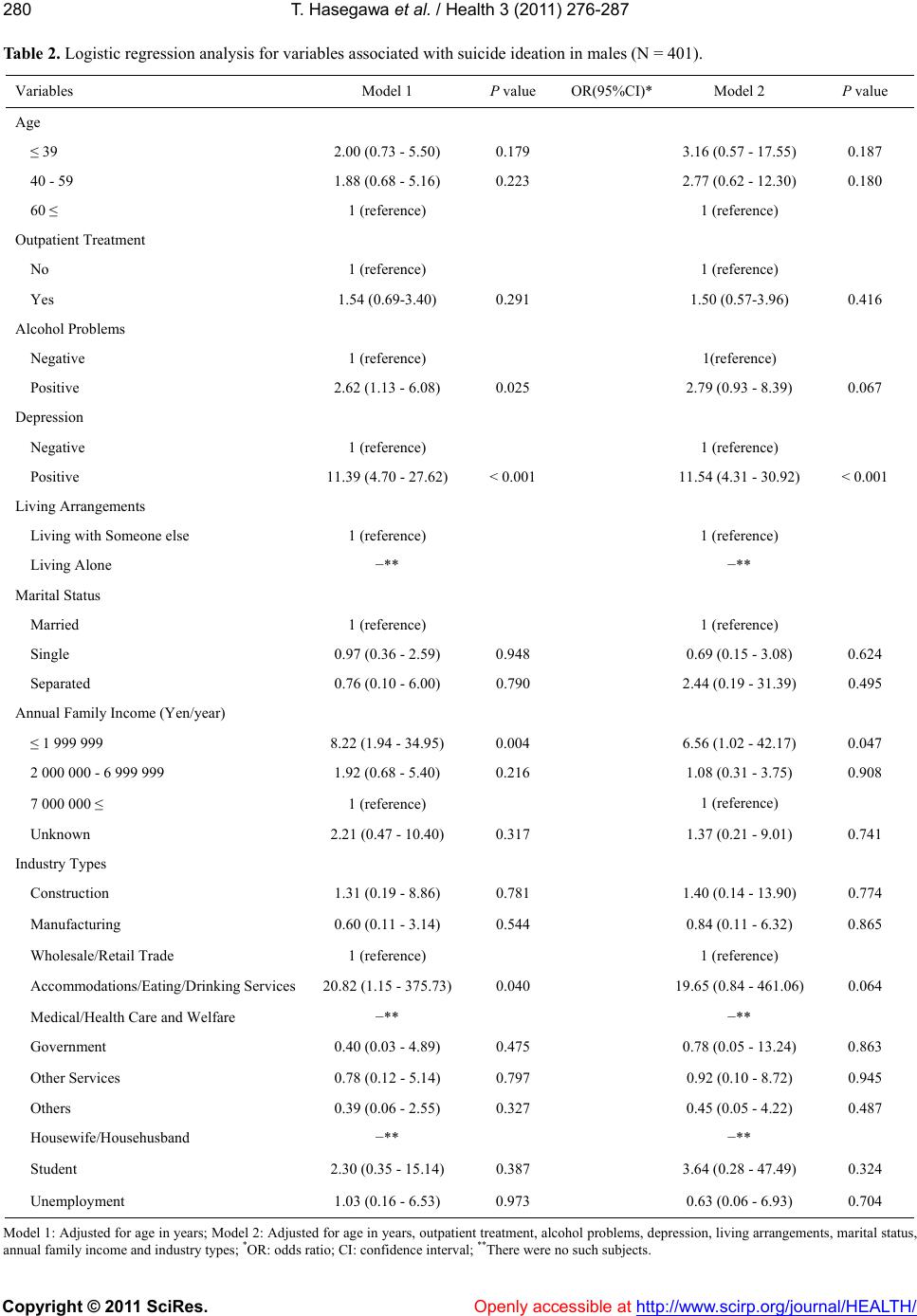

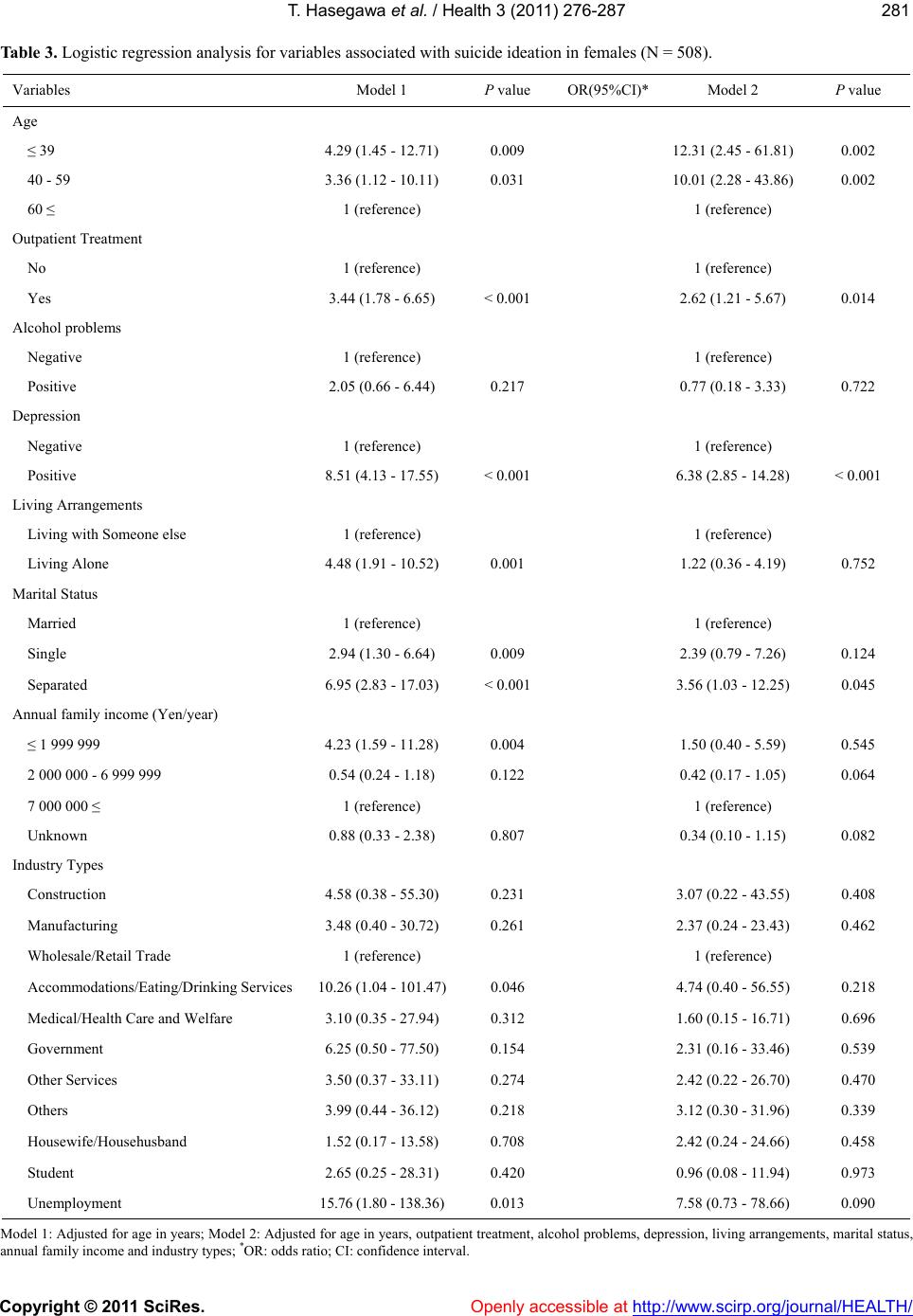

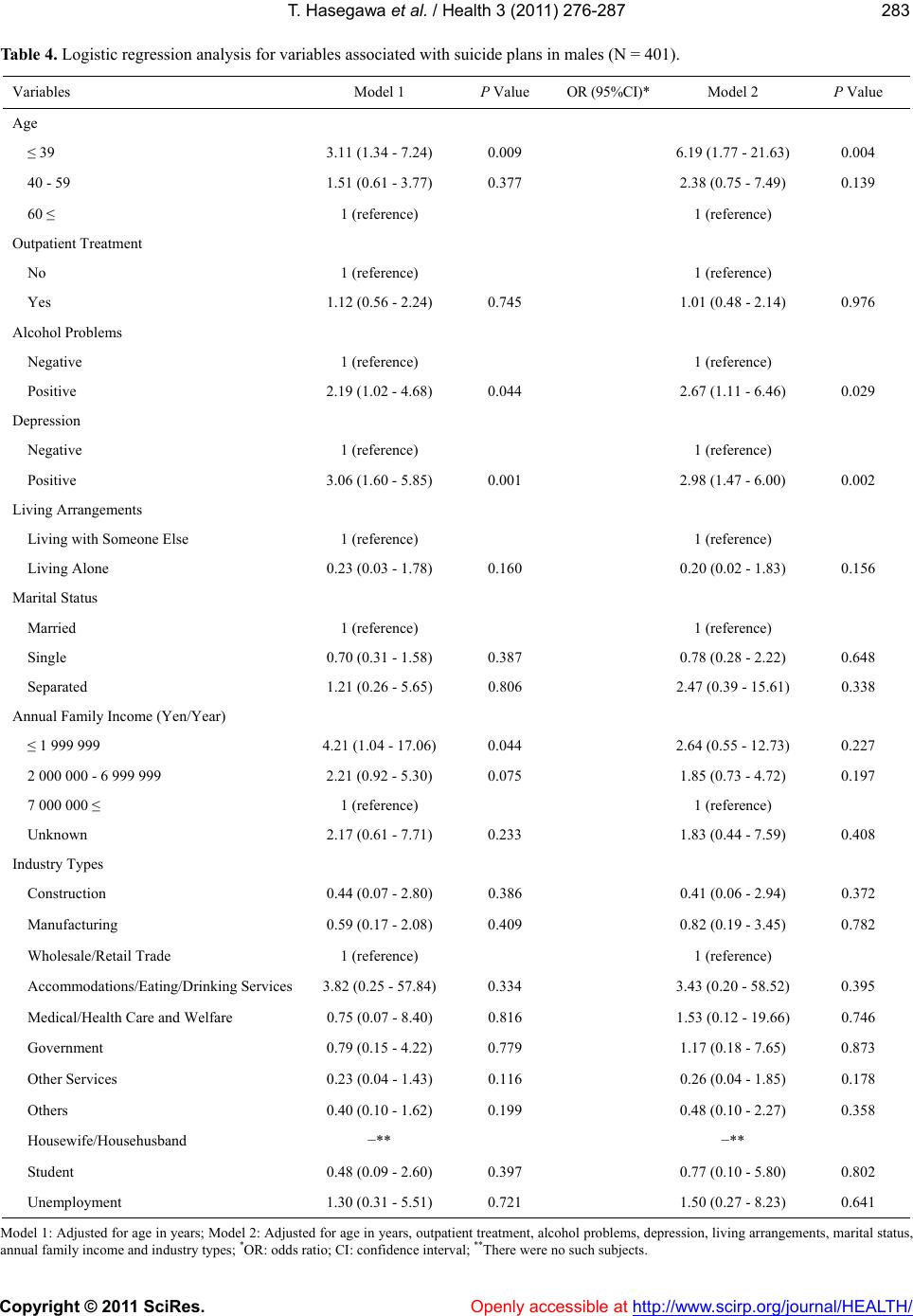

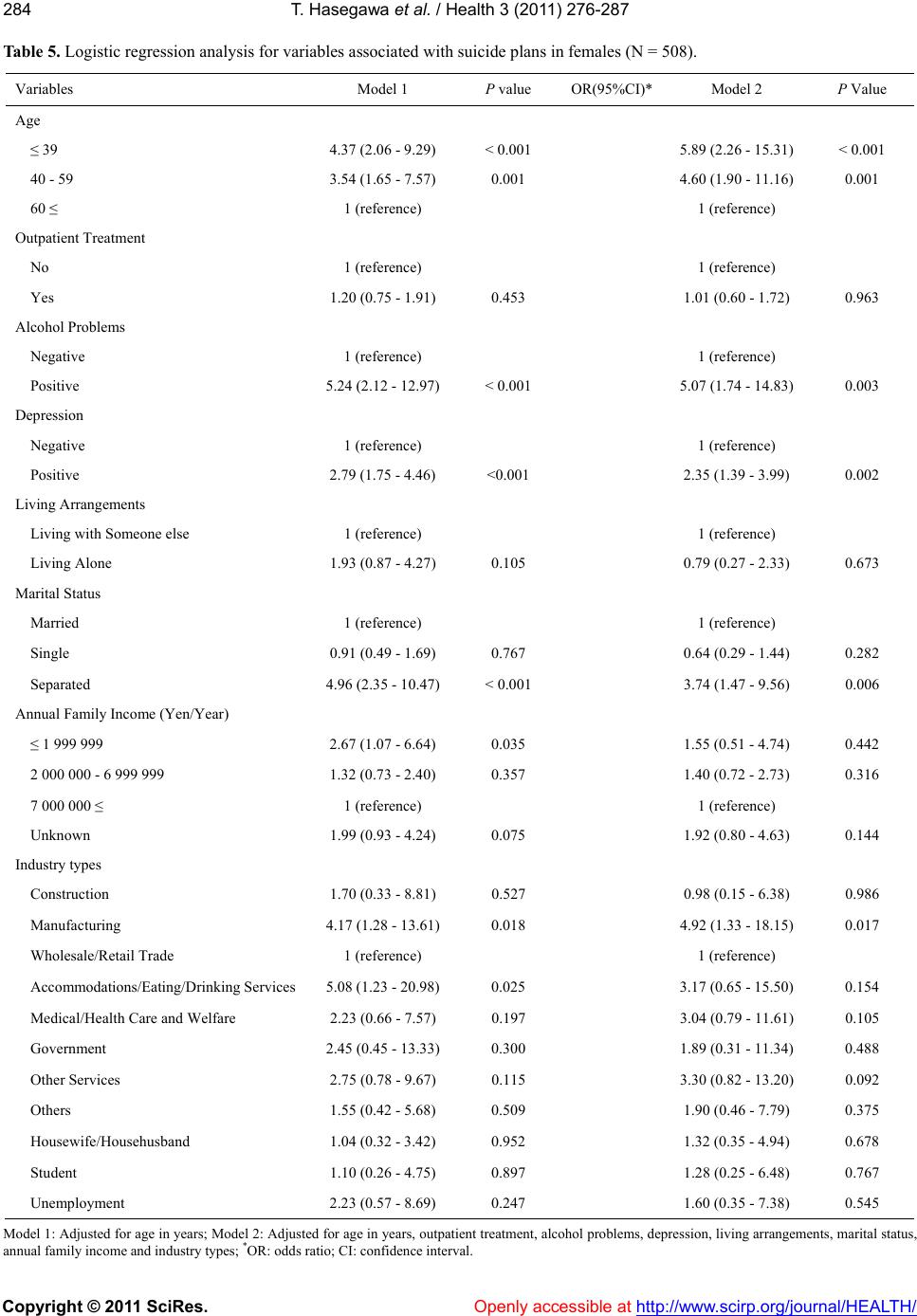

|