Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2014, 2, 28-36 Published Online July 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/gep http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/gep.2014.24005 How to cite this paper: Mystrioti, C., Xenidis, A., & Papassiopi, N. (2014). Application of Iron Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Tea for the Removal of Hexavalent Chromium in Column Tests. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2, 28-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/gep.2014.24005 Application of Iron Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Tea for the Removal of Hexavalent Chromium in Column Tests C. Mystrioti, A. Xenidis*, N. Papassiopi School of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece Email: *axen@metal.ntua.gr Received June 2014 Abstract Nano zero valent iron particles (nZVI) are popular the last few years because of the numerous ap- plications in remediation of a wide range of pollutants in contaminated soils and aquifers. The nZVI particles can be 10 - 1000 times more reactive than granular or micro-scale ZVI particles due to the small particle size, large specific surface area and high reactivity. An alternative green syn- thesis procedure was used for the production of nano zero valent iron particles (nZVI) using green tea (GT) extract, which is characterized by its high antioxidant content. Polyphenols in green tea extract possess double role in the synthesis of nZVI, because they not only reduce ferric cations, but also protect nZVI from oxidation and agglomeration as capping agents. The objective of cur- rent study was to simulate ata laboratory scale the attachment of GT-nZVI particles on soil mate- rial and study the effectiveness of attached nanoparticles for removing hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) from contaminated groundwater flowing through the porous soil bed. Column tests were carried out with various flowrates in order to examine the effect of contact time between the at- tached on porous medium nZVI and the flow-through solution on Cr(VI) reduction. After the com- pletion of column tests the soil material in each column was split in 5 vertical sections, which were further subjected to chemical analyses and leaching tests. According to the results of the study in- creasing the contact time favors the reduction and removal of Cr(VI) from the aqueous phase. The reductive precipitation of Cr can be described as a reaction that follows a pseudo-first order ki- netic law, with rate constant equal to k = 0.0 243 ± 0.0011 min−1. Leaching tests indicated that pre- cipitated chromium is not soluble. In the examined soil material, the total amount of precipitated Cr was found to range between 280 and 890 mg/(kg soil), while soluble Cr was less than 1.4 mg/kg and most probably it was due to the presence of residual Cr(VI) solution in the porosity of soil. Keywords Nanoscale Zero Valent Iron, nZVI, Hexavalent Chromium, Reductive Capacity, Column Tests 1. Introduction Chromium is widely used in a variety of industrial processes such as metal electroplating, leather tanning, man- *  C. Mystrioti et al. ufacturing of products for corrosion protection and wood preservation. The contamination of groundwater, sur- face waters and soils by hexavalent chromium, due to accidents or inefficient waste management practices re- lated with the above industrial activities, has become a high priority environmental problem. Hexavalent chro- mium presents high toxicity and can cause severe health problems due to its strong oxidizing properties. On the contrary, trivalent chromium (Cr(III)) is not toxic and presents lower water solubility and mobility than Cr(VI). Furthermore, Cr(III) is referred to be an essential micro-nutrient for many living organisms (Ghejou, 2011). Consequently the chemical reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) is an effective method for Cr(VI) remediation. Nanoscale zero valent iron has been studied extensively the last 15 years as a remarkable reductant for a va- riety of pollutants, including Cr(VI). Metallic iron, at nanoscale, combines many properties such as, small par- ticle size, large specific surface area and high surface reactivity. As a consequence, it can reduce the pollutants at a rate several orders of magnitude higher compared to the rates observed with granular ZVI particles (Ghejou, 2011). Also the colloidal suspensions of nZVI can be injected directly inside the hotspot area of contaminated aquifer, a technique which is considered to ensure lower costs and shorter remediation time compared to other remediation options, such as pump and treat methods or permeable reactive barriers (He, 2009). However, nZVI particles, if not appropriately coated, tend to aggregate and arerapidly oxidized. In order to inhibit aggregation and oxidation of iron nanoparticles many compounds have been tested as surface modifiers and stabilizers, such as hydrophilic biopolymers, carboxymethyl cellulose—CMC, chitosan, natural organic matter such as humic acid, polyelectrolytes, ion-exchange resins, and block copolymers (Bardos et al., 2011). A novel green procedure was used for the synthesis and stabilization of iron nanoparticles (nZVI) using plant extracts with high antioxidant content. The mixing of plant extracts with ferric solutions results in the production of stable dispersions of iron nanoparticles. The polyphenols of the raw materials act both as reducing and surface coating agents of nano iron particles (Hoag et al., 2009; Shahwan et al., 2011). Many environmentally friendly ma- terials, such as green tea, pomegranate, apple and oak tree leaf, etc., have been evaluated for their reducing capacity (Machado, 2012; Hoag et al., 2009). The use of nZVI was evaluated for the treatment of water or soils contami- nated with organic contaminants in numerous studies (O’Carroll et al., 2012). In comparison, the hexavalent chromium reduction with nZVI was examined in a rather limited number of studies and most of them involved only batch experiments in shaking flasks or agitated reactors (Wang et al., 2010; O’Carroll et al., 2012). In this study the reduction of Cr(VI) by nZVI was evaluated under flow conditions by conducting column tests. GT-nZVI was initially fed in the soil columns to obtain the attachment of iron nanoparticles on the soil grains. After this, groundwater contaminated with Cr(VI) was introduced in the columns to evaluate the reduc- tive capacity of attached nZVI under variable flowrate conditions. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Materials The following chemicals were used during the experimental work: ferric chloride hexahydrate (>99.0%, Merck, Germany), calcium chloride (>99.5%, Merck, Germany), potassium dichromate (>99.0%, Mallinckrodt Chemi- cal Works, USA), 1.5-diphenylcarbazide (Sigma Aldrich), potassium phthalate (>99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1.1-phenathroline (>99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich). Commercially available dry leaves of green tea (Twinings of Lon- don) were used as sources of polyphenols. Column experiments were conducted using a soil material which was a mixture of silica sand and natural soil from Asopos area (Central Greece). Collected natural soil was air dried, homogenized and sieved at −2.5 mm. Particle size analysis of the −2.5 mm part of soil indicated that it consisted of 58.9% sand, 29.6% silt and 11.5% clay. To minimize potential clogging problems during the column experiments, the natural soil was mixed with silica sand at a ratio of 50% per weight. Silica sand (origin Egypt) was obtained from Mevior SA. Sand grains were of spherical shape and their particle size ranged between 0.1 and 0.4 mm. The physical and chemical prop-erties of the final mixed soil sand are presented in Table 1. The soil-sand mixture was found to be calca- reous with a neutralizing capacity equivalent to 103 g of CaCO3 per kg and exhibiting an alkaline pH around 8.0. The chromium content of the mixture, as determined by X-Ray Fluorescence, was found to be very high, i.e. 929 mg/kg. It is noted that all Cr occurs in the trivalent state, because no Cr(VI) was detected in the sample (detec- tion limit 0.4 mg/kg). 2.2. Synthesis of nZVI The green tea extract was prepared by immersion of 20 g/L green tea leaves in water at 80˚C for 5 minutes. The  C. Mystrioti et al. extract was separated from the leaves by vacuum filtration, using a filter paper of 0.45 μm pore size. A solution of 0.1 M FeCl3 was prepared by dissolving 27 g of solid FeCl3∙6H2O in 1 L of deionized water. For the produc- tion of nZVI, the GT extract was introduced to the ferric ion solution at a 1:2 volume ratio (Hoag, 2009). Mixing was carried out at room temperature applying a vigorous agitation. To evaluate the effectiveness of nZVI pro- duction, samples of the resulting suspensions were submitted to centrifugal ultrafiltration and the ultrafiltrate was analyzed to determine the concentration of residual aqueous Fe(III) and Fe(II). It was found that only part of total Fe, i.e. ~27%, was reduced to its elemental state. Namely, the produced GT-nZVI suspensions contained approximately 1 g/L of Fe in the form of nZVI solid particles, 2.6g/L in the form of Fe(III) aqueous ions and 119 mg/L in the form of Fe(II) aqueous ions. 2.3. Column Experime n ts The detailed properties of the columns are given in Table 2. The experiments were carried out using polyethy- lene columns, with 2.63 cm internal diameter and ~10 cm length. The columns were filled with 60 - 64 g of the soil material and occupied a total volume of approximately 46 mL. The soil was placed manually and gently vi- brated at several stages to ensure uniform packing. The final bulk density, which is a measure of the obtained packing, ranged between 1.32 and 1.38 g/cm3. Each packed column was connected to a peristaltic pump (Alitea, Sweden) and to a reservoir, which con- tained the fluids prepared for introduction in the column. Introduction of fluids was carried out in an upflow mode. Table 1. Physicochemical characteristics of soil material. Properties Sand/Silt/Clay, % 79.4/14.8/5.8 pH 7.65 NP(a), gCaCO3/kg 103 Organic Carbon(b), % 0.33 Fe, mg/kg 19760 Ca, mg/kg 62000 Cr, mg/kg 929 (a)Neutralizing Potential (NP), according to Lawrence and Wang (1997); (b)Nelson and Sommers (1996). Table 2. Properties and operating conditions of columns. Parameter Columns Control I II Soil material dry mass, M (g) 60.3 63.7 60.9 Column diameter, D (cm) 2.63 2.63 2.63 Bed height, L (cm) 8.50 8.50 8.50 Bed Volume, BV (cm3) 46.2 46.2 46.2 Particle density, ρp(a) (g/cm3) 2.30 2.30 2.30 Dry bulk density, ρb(b) (g/cm3) 1.32 1.38 1.32 Porosity, θ(c) 0.43 0.40 0.43 Pore volume size, VPV (cm3) 19.9 18.4 19.7 GT-nZVI loading (mL) -- 210 210 Cr(VI) solut. flowrate, Q (mL/min) 1.2 1.2 4.8 (a)Calculated based on the particle densities of sand 2.50 g/cm3 and soil 2.16 g/cm3. (b)Dry bulk density: ρb = M/BV. (c)Porosity: θ = 1 − ρb/ρp.  C. Mystrioti et al. Three similar columns were prepared. The first column served as control, which means that it was not loaded with nZVI. The other two columns were loaded with the same amount of GT-nZVI, i.e. 210 mL of suspension, which is equivalent to approximately 11 pore volumes (PVs). The size of pore volume is calculated from the to- tal bed volume (BV) and the porosity (θ) of each column: (1) A previous study had indicated that this soil material can retain a maximum amount of nZVI corresponding to the introduction of ~40 PVs of the GT-nZVI suspension (Mystrioti et al., 2014). Current experimental work was carried out applying a lower loading, corresponding to ~28 % of the maximum retention capacity of soil. A Cr(VI) contaminated water was introduced in all three columns. Feeding flowrate was equal to 1.2 mL/min in the Control column and in column I and 4.8 mL/min in column II. The whole experimental procedure included the following steps: S1. The packed columns were first saturated with a background solution containing 6.6 mM CaCl2, by intro- ducing140 mL (~7.4 PVs) of the solution in the column. S2. An amount of 210 mL (~11 PVs) of GT-nZVI suspension was introduced in columns I and II. S3. Background solution, 70 mL (~3.7 PVs), was again introduced to elute eventual residual species of the iron suspension S4. Finally a solution simulating Cr(VI) contaminated groundwater was introduced in the columns. The solu- tion contained 5 mg/L of Cr(VI) and 6.6 mM of CaCl2. The total volume was 2120 mL (107 PVs) in the case of Control column, 10,400 mL (565 PVs) in column I and 9350 (475 PVs) in column II. The fluids in steps S1, S2, and S3 were introduced with a constant flowrate of 1.2 mL/min. Varied flowrate was applied only in step S4. It is also noted that steps S2 and S3 were omitted in the Control column. Column effluents were sampled and analyzed for pH, Eh, conductivity, dissolved oxygen and concentrations of total Fe, total Cr and Cr(VI). 2.4. Soil Material Examination after the End of Column Tests After the completion of Cr(VI) flow through the columns, the soil material of columns was split in 5 vertical sections, which were examined by detailed chemical analyses. Representative samples of the 5 soil sections were also subjected to the ΕΝ12457.02 standard leaching test procedure, to evaluate the stability of precipitated Cr compounds. The leaching tests were conducted by adding 3grams of sample in 30 mL of deionized water and the suspensions were kept under agitation for 24 hours. After this period, the suspensions were filtered and the aqueous solutions were analyzed for total Cr and Fe. 2.5. Analytical Metho ds Elemental analysis of soil material before and after the column tests was conducted applying the X-Ray Fluo- rescence (XRF) technique. The measurements were carried out using a XEPOS spectrometer equipped with x- lab-pro software. Total Fe and Cr concentrations in aqueous solutions were determined by Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy- Flame Emission, AAS-FE. Low Cr concentrations were measured by ICP-MS (Thermo Scientific, X Series II). Ferrous ion was measured by the phenanthroline method.Chromate analysis was carried out using the diphenyl- carbazide method. The pH and redox potential were measured using the pH meter Metrohm 827 pH Lab and a redox electrode 691 with a reference electrode Ag/AgCl/3 M KCl (Metrohm). The dissolved oxygen and the conductivity were monitored using an electrode DO (WTW, Oxi 330i) and conductivity meter (WTW, LF 95). 3. Results and Discussion 3.1. Column Experiments Results Representative results of column tests are shown in the charts of Figure 1. In these charts the amount of fluids supplied in the columns was expressed as number of Pore Volumes (PVs). This expression, which is often used in column and hydrogeological studies, facilitates scale-up calculations, based on the porosity of contaminated aquifers.  C. Mystrioti et al. (a) (b) (c) Figure 1. (a) Evolution of pH during the 4 steps of operation; (b) Total concentration of Fe in the effluents of Columns I and II; (c) Breakthrough curves of Cr(VI) in the three columns. The volume of fluids supplied in the columns is expressed as number of pore volumes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0100 200 300 400 500 600 pH Number of Pore Volumes Inflow Control Outflow Column I outflow Column II outflow 0.1 1 10 100 1000 10000 0100 200 300 400 500 600 Fe(tot), mg/L Number of Pore Volumes Inflow Column I outflow Column II outflow S2 Detection limit 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 0100 200 300 400 500 600 Cr,(VI) mg/L Number of Pore Volumes Inflow Control outflow Column I outflow Column II outflow  C. Mystrioti et al. The evolution of pH in the columns during the 4 steps of operation and the concentration of Cr(VI) in the ef- fluents of the 3 columns is shown in Figure 1(a). The dotted curve represents the pH of inflow solutions. The background solution, which was supplied during steps S1 and S3, has a pH of 5.5. GT-nZVI suspension, which was fed in Columns I and II during step S2, has a very acidic pH equal to 1.7. The acidity of GT-nZVI suspen- sion is due to the generation of H+ during the reduction of Fe(III) to the elemental state, Fe(0), as shown in reac- tion (2): ()( ) 30 n nFe3 Ar-OHnFe3nAr=O3nH ++ +→+ + (2) where (Ar-OH)n represents GT polyphenols. The soil material neutralizes part of the introduced acidity due to the contained CaCO3. The pH of effluents is systematically higher compared to that of influents. During the introduction of acidic GT-nZVI suspension in Columns I and II the pH of effluents becomes slightly acidic, but it does not drop below the value of 5.2. During the addition of Cr(VI) solution the pH of effluents is buffered close to neutral values, ranging between 7.0 - 7.5 in all the columns. Iron was detected in the effluents of Columns I and II only for a few number of pore volumes during the in- troduction of GT-nZVI in step S2 (Figure 2(b)). Speciation analyses of effluents indicated that all eluted iron was only in the form of aqueous Fe ions. As already mentioned, the reduction of Fe(III) according to Equation (2) during the synthesis of nZVI is partial and the resulting suspension contains approximately 2.6g/L of Fe in the form of aqueous Fe(III), and 1.0 g/L in the form of nZVI solid particles. Mass balance calculations during column experiments indicated that only a small part of aqueous Fe(III) was recovered in the effluents, while the major part was retained in the columns, due to the precipitation of Fe(OH)3 according to reaction (3): ()( )()()() ( ) 32 32 23 Fe aq 3CaCOs 3HO3COg 3CaaqFeOH s ++ ++→++ (3) Summarizing the results regarding mass balance calculations of iron, from the 280 mg of iron fed to Columns I and II, approximately 210 mg were retained inside the soil material as nZVI and 460 mg as Fe(OH)3, while 110 mg were eluted with the background solution as aqueous Fe species. The concentration of Cr(VI) in the effluents is shown in Figure 1(c). As seen in the figure, soil material in the Control column is not able to reduce or adsorb any appreciable amount of Cr(VI). Chromate concentration in the effluents becomes almost equal to that in the influents after the supply of approximately 3.5 PVs of solution. In contrast, Columns I and II, which were treated with GT-nZVI suspension, can retain an important amount of Cr(VI). Retention occurs through the reduction of Cr(VI) in the trivalent state under the action of ZVI nanopar- ticles, and the precipitation of Cr(III) in the form of mixed Fe-Cr oxyhydroxides. A typical reaction describing the reductive precipitation of Cr(VI) is given in Equation (4): ()() ( ) 20 42 33 CrOFe2H2H OFeOHCrOHs −+ ++ +→⋅ (4) The experiments in column I were conducted by interrupting the supply of Cr(VI) solution during the nights and the weekends and for this reason the shape of the breakthrough curve is not smooth. The Cr(VI) concentra- tion in the effluents after each interruption was lower than the previous one suggesting that an increase of con- tact time favors the reduction and removal of Cr(VI) from the aqueous phase. The execution of experiments in column II was carried out without interrupting the inflow of Cr(VI) solution and for this reason the shape of breakthrough curve was smoother. Three stages can be distinguished during the supply of Cr(VI) in Columns I and II. The initial stage corres- ponds to the complete reduction and removal of Cr(VI) from the aqueous solution. This stage lasted for ap- proximately 50 PVs of Cr(VI) solution in Column I and 40 PVs in Column II. A gradual decline in the perfor- mance of nZVI-loaded columns was recorded after this initial stage and finally steady state conditions were es- tablished in their operation after the introduction of ~200 and 240 PVs of Cr(VI) solution in columns I and II respectively. Both columns reached a plateau which is equal to 3.5 mg/L of Cr(VI) in the effluent for column I and 4.5mg/L for column II. This value is by 1.5 mg/L and 0.5mg/L lower compared to the concentration of Cr(VI) in the feed solution, i.e. 5 mg/L. The appearance of this plateau suggests that the soil columns maintain a certain reductive capacity but there is a kinetic limitation for the reduction of Cr(VI) to the Cr(III) state during the flow of solution through the column. Assuming a pseudo-first order kinetics, the concentration of Cr(VI) in the effluent, Cef, is related with the concentration in the influent, Cin, according to Equation (5):  C. Mystrioti et al. (a) (b) (c) Figure 2. (a) Iron (b) calcium and (c) chromium content in the five sections of soil material in Column I after the completion of tests in comparison with the concentrations in initial soil. ef in CθL ln kτk Cu ⋅ =−=− (5) where k is the rate constant of the pseudo-first order kinetic law, τ is the residence time of solution in contact 010000 20000 30000 40000 bottom lower middle middle upper middle top Fe(tot), mg/kg Soil slices Initial soil Column I 020000 40000 60000 80000 bottom lower middle middle upper middle top Ca, mg/kg Soil slices Initial soil Column I 05001000 1500 2000 bottom lower middle middle upper middle top Cr(tot), mg/kg Soil slices Initial soil Column I  C. Mystrioti et al. with the nZVI loaded soil material inside the column, θ the porosity, L the length of soil bed and u the Darcy velocity of the solution, calculated from the volumetric flowrate Q and column cross section according to Equa- tion (6): (6) In the case of Column I with θ = 0.40, L = 8.5 cm, Cef = 3.5 mg/L and Q = 1.2 ml/min, the value of rate con- stant k is calculated to be equal to 0.0232 min−1. For Column II with θ = 0.43, L = 8.5 cm, Cef = 4.5 mg/L and Q = 4.8 ml/min, the value of k is 0.0254 min−1. The two values of k are very close supporting the assumption of pseudo-first order kinetic law. Based on these experiments, the mean value of rate constant and the relative dif- ference of estimates is k = 0.0243 ± 0.0011 min−1. 3.2. Characteristics of Soil Material after Completion of Tests The concentrations of iron, calcium and chromiumin the successive layers of Column I are shown in Figures 2(a)-(c). As seen in Figure 2(a), the Fe content of soil after the completion of tests is higher compared to the in- itial soil material. Namely, initial concentration of Fe was 19,760 mg/kg and increased up to approximately 36,000 mg/kg in the two lower slices of soil bed, 30,000 mg/kg in the middle and upper middle slice and close to 24,000 in the top slice. Increase of Fe concentration occurs during the introduction of GT-nZVI suspension in the column (operation step S2) and is related with the precipitation of aqueous Fe(aq) according to reaction (3) and the simultaneous attachment of nZVI particles in the precipitates. Figure 2(b) illustrates the gradual decrease of Ca content in the five slices of soil, which is due to the dissolu- tion of soil calcite as described in reaction (3). Finally, Figure 2(c) shows the gradual accumulation of Cr, which takes place during the supply of Cr(VI) solution in the column (operation step S4) and is due to the reductive precipitation of Cr according to equation (4). The concentration of Cr in initial soil was 929 mg/kg and increased up to 1820 mg/kg in the bottom slice, and 1410, 1310 and 1210 mg/kg in the three subsequent slices of soil. Leaching tests were carried out to evaluate the stability of precipitated chromium. The results of the tests showed that soluble chromium was almost equal in the five layers of soil column, ranging between 0.8 and 1.4 mg/kg. This is a very low amount compared to the total mass of precipitated Cr, which varied from 280 to 890 mg/kg. However, it is much higher in comparison with the theoretic solubility of Fe(OH)3Cr(OH)3. According to published thermodynamic data the solubility of mixed Fe(OH)3∙Cr(OH)3 in near neutral pHs is expected to be in the order of 0.003 mg/L (Sass & Ray, 1987; Papassiopi et al., 2014). This concentration in the aqueous phase corresponds to an amount of soluble Cr equivalent to 0.03 mg per kg soil, when the leaching tests are carried out according to the protocol of ΕΝ12457.02 test, i.e. with a liquid to solid ratio 10 mL per gram soil. The compara- tively high concentrations of measured soluble Cr can be attributed to the fact that the soil layers were not washed before the execution of leaching tests. As a consequence they contained in their porosity the residual Cr(VI) solution supplied during the column experiments. Mass balance calculations justify this assumption. 4. Conclusion Polyphenol coated nZVI particles have been synthesized mixing Green Tea extract with a FeCl3 solution. The resulting GT-nZVI suspension was found to contain approximately 1.0 g/L of Fe in the form of ZVI nanopar- ticles, 2.6 g/L Fe as residual aqueous Fe(III) and 119 mg/L in the form of Fe(II) aqueous ions. GT-nZVI suspension was introduced in columns containing a calcareous soil material. The presence of calcite caused the precipitation of aqueous Fe(III) in the form of iron oxyhydroxides and the retention of nZVI particles inside the soil columns. The Cr(VI) reducing effectiveness of soil columns, containing the nZVI particles, was evaluated by introducing a solution containing 5 mg/L of Cr(VI) with two different flowrates. Complete reduc- tion and removal of Cr(VI) was observed for an amount of solution corresponding approximately to 50 PVs for Column I and 40PVs for Column II respectively. A gradual decline in the performance of nZVI-loaded columns was recorded after this initial stage and finally steady state conditions were established in their operation after the introduction of ~200 and 240 PVs of Cr(VI) solution in columns I and II. The performance of columns at steady state conditions suggests that there is a kinetic limitation for the reduction of Cr(VI) to the Cr(III) state at this stage. This limitation can be described as a reaction that follows a pseudo-first order kinetic law, with rate constant equal to k = 0.0243 ± 0.0011 min−1.  C. Mystrioti et al. Acknowledgements This research has been co-financed by the European Union (European Social Fund—ESF) and Greek national funds through the Operational Program “Education and Lifelong Learning” of the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF)-Research Funding Program: Heracleitus II. Investing in knowledge society through the Eu- ropean Social Fund. The authors thank Prof. G. Demopoulos, McGill University, for his contribution to this study. References Bardos, P., Bone, B., Elliott, D., Hartog, N., Henstock, J., & Nathana il, P. (2011). A Risk/Benefit Approach to the Applica- tion of Iron Nanoparticles for the Remediation of Contaminated Sites in the Environment. Gheju, M. (2011). Hexavalent Chromium Reduction with Zero Valent Iron (ZVI) in Aquatic Systems. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 222, 103-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11270-011-0812-y He, F., Zhang, M., Qian, T., & Zhao, D. (2009). Transport of Carboxymethyl Cellulose Stabilized Iron Nanoparticles in Porous Media: Column Experiments and Modeling. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 334, 96-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2009.02.058 Hoag, G., & Collins, J. (2009). Degradation of Bromothymol Blue by “Greener” Nano-Scale Zero-Valent Iron Synthesized Using Tea Polyphenols. Journal of Material Chemistry, 19, 8671-8677. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/b909148c Lawrence, R. W., & Wang, Y. (1997). Determination of Neutralization Potential in the Prediction of Acid Rock Drainage. Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Acid Rock Drainage, Vancouver, 449-464. Machado, S., Pinto, S. L., Grosso, J. P., Nouws, H. P. A., Albergaria, J. T., & Delerue-Mat os, C. (2013). Green Production of Zero-Valent Iron Nanoparticles Using Tree Leaf Extracts. Science of the Total Environment, 445-446, 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.033 Mystrioti, C., Xenidis, A., Papassiopi, N., Dermatas, D., & Chrysochoou, M. (2014). Fate of Green Tea Iron Nanoparticles in Calcareous Soils. Proceedings of Geo-Congress, Geo-Characterization and Modeling for Sustainability, Atlanta. Nelson, D. W., & Sommers, L. E. (1996). Total Carbon, Organic Carbon and Organic Matter. In D.L. Sparks et al. (Eds.), Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3—Chemical Methods (pp. 961-1010). Madison: SSSA Book Ser. 5. O’Carroll, D., Sleep, B., Krol, M., Boparai, H., & Kocur, C. (2013). Nanoscale Zero Valent Iron and Bimetallic Particles for Contaminated Site Remediation. Advances in Water Resources, 51, 104-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2012.02.005 Papassiopi, N., Vaxevanidou, K., Christou, C., Karagianni, E., & Antipas, G. S. E. (2014). Synthesis, Characterization and Stability of Cr(III) and Fe(III) Hydroxides. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 264, 490-497. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.09.058 Sass, B. M., & Rai, D. (1987). Solubility of Amorphous Chromium(III)-Iron(III) Hydroxidesolid Solutions. Inorganic Che- mistry, 26, 2228-2232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ic00261a013 Shahwan, T., Abu Sirriah, S., Nairat, M., Boyacı, E., Eroglu, A., Scott, T., & Hallam, K. (2011). Green Synthesis of Iron Nanoparticles and Their Application as a Fenton-Like Catalyst for the Degradation of Aqueous Cationic and Anionic Dyes. Chemical Engineering Journal, 172, 258-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.05.103 Wang, Q., Qian, H., Yang, Y., Zhang, Z., Naman, C., & Xu, X. (2010). Reduction of Hexavalent Chromium by Carboxyme- thyl Cellulose-Stabilized Zero-Valent Iron Nanoparticles. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 114, 35-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2010.02.006

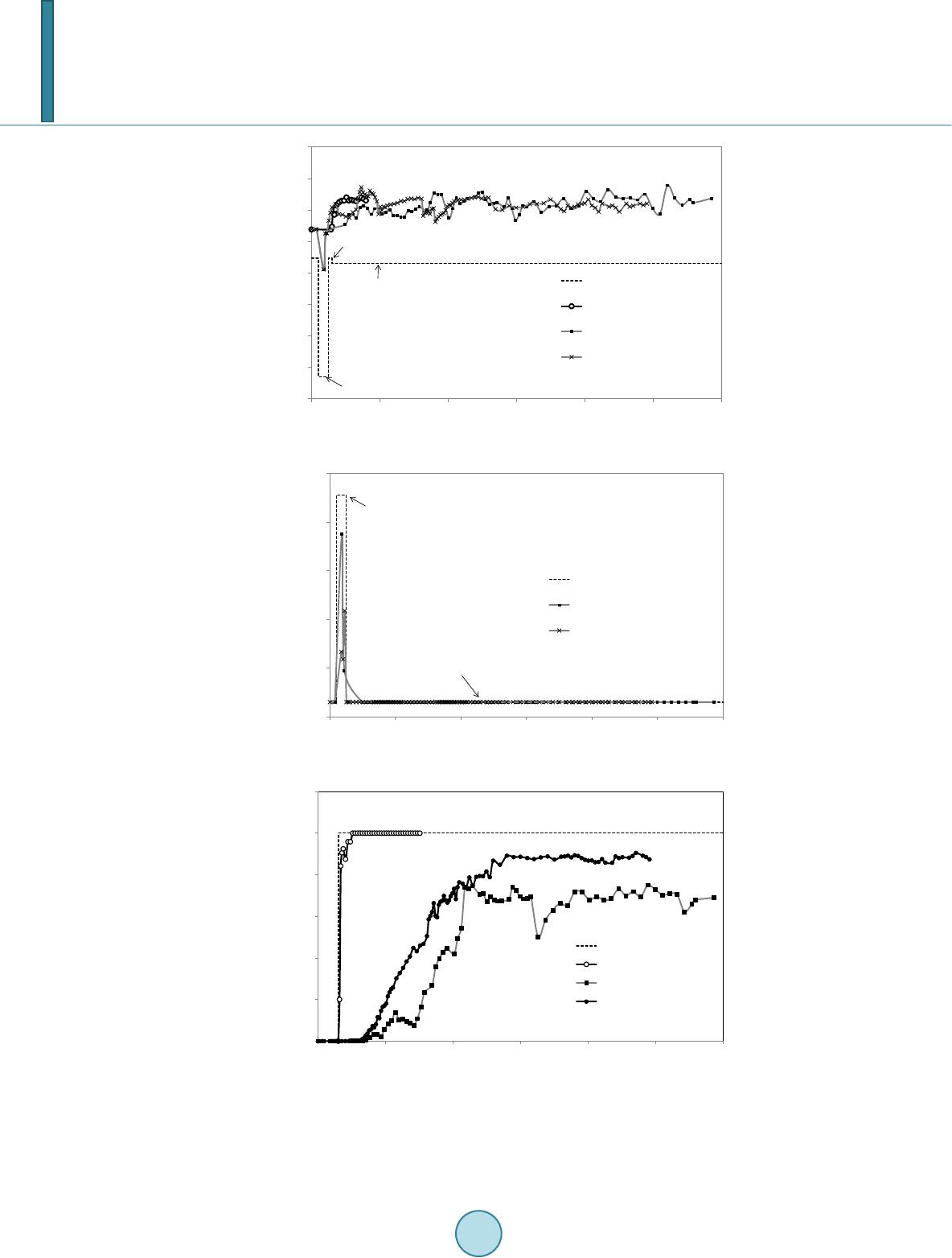

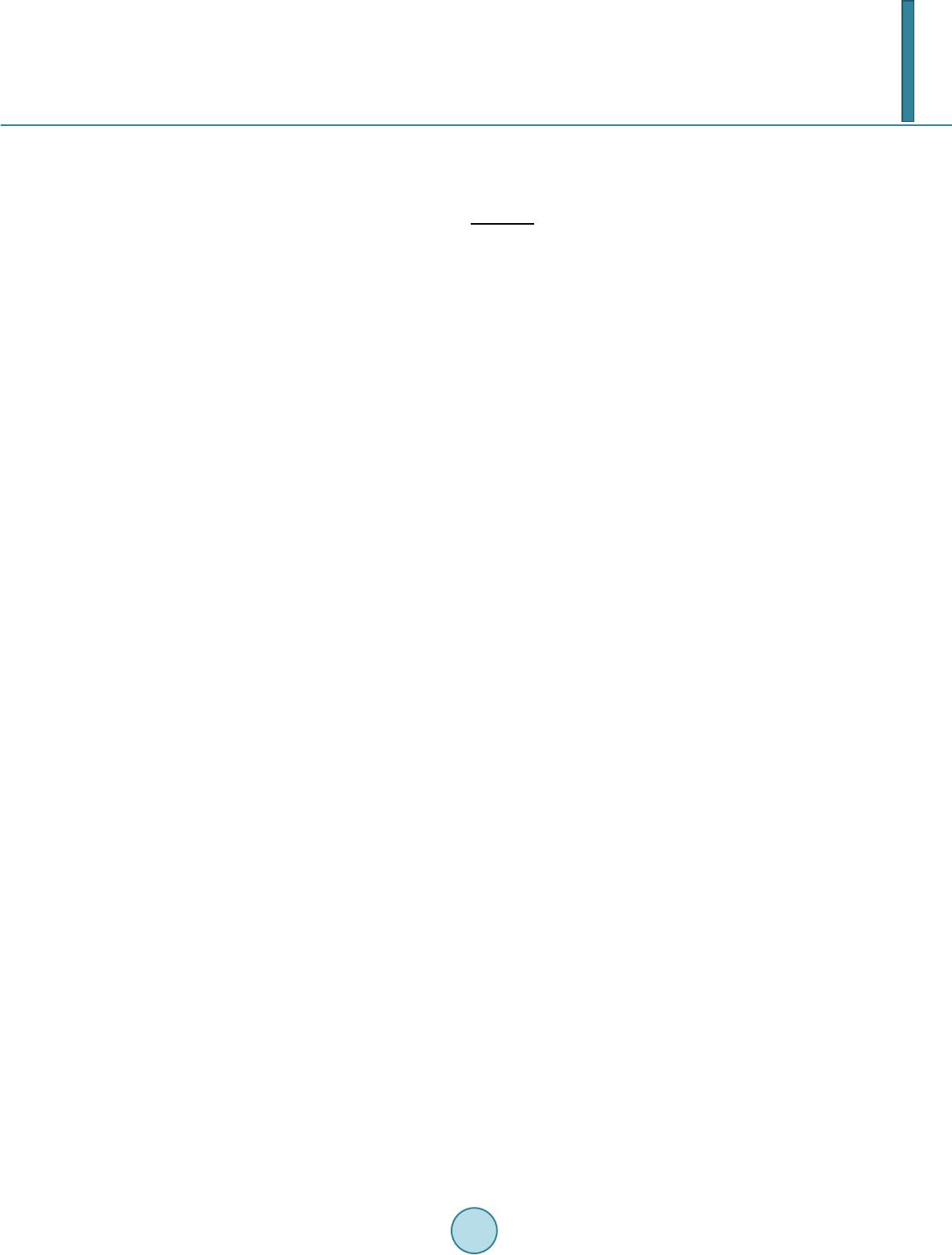

|