Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.2, 109-116 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.22018 Morphological Knowledge and Decoding Skills of Deaf Readers* M. Diane Clark, Gizelle Gilbert, Melissa L. Anderson Science of Learning Center on Visual Language and Visual Learning, Washington, DC, USA Department of Educational Foundations and Research, Gallaudet University, Washington, D.C., USA. Email: diane.clark@gallaudet.edu Received January 4th, 2011; revised February 9th, 2011; accepted February 14th, 2011. Many studies have reported the necessity of phonological awareness to become a skilled reader, citing barriers to phonological information as the cause for reading difficulties experienced by deaf individuals. In contrast, other research suggests that phonological awareness is not necessary for reading acquisition, citing the importance of higher levels of syntactic and semantic knowledge. To determine if deaf students with higher language skills have better word decoding strategies, students responded to a morphological test, where monomorphemic words and multimorphemic words were matched to their definitions. Two studies are reported, one focusing on English placement levels and a second with formal measures of both ASL and English language proficiency. Results in- dicated that performance on the morphological decoding test was related to language proficiency scores, but not to phonological awaren e s s scores. Keywords: Deaf, Reading, Morphology Research on the reading achievement of deaf individuals in- dicates that deaf readers tend to lag behind their hearing peers, with an average reading level equivalent to the fourth grade (Allen, 1986; Conrad, 1979). Unfortunately, this achievement gap between deaf and hearing readers has remained fairly stable over the past 30 to 40 years (e.g. Strong & Prinz, 1997; Mus- selman, 2000). To explain this issue a number of researchers have hypothesized the cause of deaf individuals’ reading diffi- culties. Phonologi cal Awarenes s and Reading Skill One commonly cited hypothesis suggests that phonological awareness is required to become a skilled reader (Colin, Mag- nan, Ecalle, & Leybaert, 2007; Luetke-Stahlman & Nielsen, 2003; Paul, Wang, Trezek, & Luckner, 2009; Perfetti & Sandak, 2000; Wang, Trezek, Luckner, & Paul, 2008). The phonologi- cal coding deficit hypothesis theorizes that lower reading levels for prelingually deaf readers are primarily a failure to effec- tively process written text at the lexical level (e.g., Kelly & Barac-Cikoja, 2007). The central claim underlying this view is that, due to a lack of auditory stimulation, prelingually deaf readers do not develop phonemic awareness (e.g., Charlier & Leybaert, 2000; Dyer, MacSweeney, Szczerbinski, Green, & Campbell, 2003; Hanson & Fowler, 1987; Hanson & McGarr, 1989; Miller, 1997, 2006a, 2006b; 2007a; Sutcliffe, Dowker, & Campbell, 1999; Transler, Leybaert, & Gombert, 1999). In turn, this problem of ineffective phonological knowledge prevents rapid and accurate phonological decoding of written words (e.g., Leybaert, & Alegria, 1993; Perfetti & Sandak, 2000). As a consequence, the integration of the meaning of such words into broader ideas via their structural (syntactic) and semantic proc- essing is also limited and likely to fail. Advocating a lexical/phonological coding deficit hypothesis for the explanation of reading failure in prelingual deaf readers intuitively makes sense given that specific reading disorders in hearing readers coincide with marked deficits in the phono- logical domain (Ehri, Nunes, Stahl, & Willows, 2001b; Frost, 1998; Hulme, Snowling, Caravolas, & Carroll, 2005; Report of the National Reading Panel, 2000; Snow, Burns & Griffin, 1998; Share, 1995, 2004, 2008; Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2005; Troia, 2004; Vellutino, Fletcher, Snowling, & Scanlon, 2004). Moreover, predictions made by the hypothesis are in accor- dance with evidence obtained from short-term recall experi- ments suggesting that better deaf readers tend to recode written stimuli into a phonological code–as indicated by their sensitiv- ity to phonological manipulations introduced into the phono- logical properties of the to-be-recalled written stimuli (letters or words) (e.g., Conrad, 1979; Hanson, 1982; Hanson, Liberman & Shankweiler, 1984; Hanson & Lichtenstein, 1990; Harris & Moreno, 2006; Krakow & Hanson, 1985). In contrast, some recent lines of research suggest that pho- nological awareness is not the only route to becoming a skilled deaf reader (Allen, Clark, del Giudice, Lieberman, Mayberry, et al., 2009; Izzo, 2002; Miller, 2005a; Miller & Clark, in press). A project by Izzo (2002), on the comprehension of written ma- terials, found that deaf college students did not rely on phono- logical knowledge when reading. Rather, it seemed that skilled deaf readers relied on other higher-order metacognitive skills to decode words. Additionally, Schirmer and Williams (2003) found that highly-skilled deaf readers had more developed metacognitive abilities than less-skilled deaf readers, suggesting *Data for this paper was collected with the support of the Gallaudet Re- search Institute (GRI) Priority Grant Program, a GRI Small Grant to Jona- than Penny and NSF’s Science of Learning Center on Visual Language and Visual Learning (VL2) grant number SBE-0541953.Part of this research was presented at the 2008 Association for Psychological Sciencemeeting in Chicago, Illinois and the 2009 Association for Psychological Science meet- ing in San Francisco.  M. D. CLARK ET AL. 110 a relationship between reading skills and higher-order metacog- nitive skills. Findings like these, as well as those reported by Narr (2008), seem to imply that phonology per se does not enhance reading comprehension in individuals with significant prelingual hearing losses. A similar conclusion has been drawn from a systematically conducted large scale meta-analysis of 58 studies (2145 tested individuals) designed to clarify the contri- bution of prelingually deaf readers’ phonologi- cal processing skills to their reading comprehension (Mayberry, Del Giudice, Lieberman, 2011). Findings from this meta-analysis strongly suggest that phonological coding is not the cause of low read- ing ability in the deaf population. Morphological Awareness and Reading Skill One metacognitive skill that has been found to play a role in reading achievement is morphological knowledge. The afore- mentioned research by Izzo (2002) indicated that deaf individu- als rely on fingerspelling to identify words, suggesting that the reading abilities of deaf students are accounted for by their decoding skills at both the letter and morpheme levels. Indeed, morphology has often been suggested to be important for learning basic reading skills for both hearing and deaf children. The morphographic model for word identification identifies three stages of visual analysis in the decoding of hearing chil- dren: logographic, alphabetic, and orthographic (Frith, 1985). The logographic stage involves the use of visual skills, mean- ingful exposure to print, and word knowledge to supply the reader with contextual information necessary for word decod- ing. Visual discrimination is also a key element of the alpha- betic, or “sounding out,” stage, which relies on phonological awareness for decoding. The third and final stage is the analysis of words into larger orthographic units, which Ehri (1992) la- bels “cipher sight word reading.” However, it is important to note that these three types of vis- ual analysis may not apply to readers who lack easy access to phonology for word decoding. Rather, deaf individuals who lack access to phonological information may not rely on “sounding out” for decoding; instead they could use contextual information and sight word identification. Indeed, Gaustad (2000) reported that deaf individuals who are unable to recode to speech primarily use sight word identification to identify monomorphemic words. Gaustad further theorized that deaf readers approach reading using three strategies: “1) the intent to analyze words, 2) well-developed visual skills and segmental awareness (morphological and orthographic), and 3) experience with the connections between printed (morphographic) seg- ments of words and the meanings they encode” (2000, p. 66). Additionally, she suggests that deaf students first learn to use morphographic analysis when they are exposed to multimor- phemic words. As morphology is visually accessible, it can serve as an al- ternate strategy to phonology for deaf readers acquiring vo- cabulary knowledge and higher-order reading skills. In support of this idea, Ehri (1992) reported that individuals who are skilled readers of English pay more attention to the visual composition of words than their phonological composition. This switch may be due to the finding that phonological re- coding is a slower process than sight word reading for a reader who has yet to ma ster the phonologic al system (Ma rslen-Wilson, Komisarjevsky, Waksler, & Older, 1994). While phonological recoding is a slow process for these individuals, it is possible to increase use of the visual channel for word identification by increasing knowledge of the morphological structure of words. Indeed, with this knowledge of morphological structure, in- cluding awareness of negation, tense, and possession, young deaf children are capable of manipulating basic English text (Gaustad, 2000). Research Objective Decoding is an important component of reading that permits moving from the printed form to the internal lexicon. The use of morphology facilitates word decoding in two ways: 1) through a direct link between orthographic strings and their corre- sponding lexical meaning, and 2) through the ability to decode novel mulitmorphemic strings into their individual components (Gaustad, 2000). The current project sought to investigate if deaf college students use contextual information present in multimorphemic low-frequency words to determine their defi- nitions. As one component of this contextual information, pho- nological word-decoding strategies were also investigated as they related to English placement levels. Study 1 Research Question and Hypotheses The first portion of this study investigated whether English placement levels predict deaf college students’ morphological and phonological word-decoding strategies. Hypothesis 1: Deaf students with higher English placement levels will exhibit increased morphological decoding skills, demonstrated by higher levels of accuracy on a morphological word-decoding task. Hypothesis 2: Deaf students with higher English placement levels will exhibit increased phonological decoding skills, demonstrated by higher levels of accuracy on a phonological awareness task. Method Measures English Placement. A proxy for English fluency was devel- oped based on the level of English placement assigned to each student as they matriculated into the university. The four groups of English placement are as follows: Developmental, Entry Level, Advanced, and Honors. Placement is determined by the Degrees of Reading Power exam (DRP), a test designed to measure students’ strengths and weaknesses in reading. More importantly, the DRP is designed to measure students’ expertise in reading under “real life” conditions (Department of Program Services–Student Assessment Office, 2003). The criterion va- lidity of the DRP has been established through positive correla- tions with both the Nelson-Denny Reading Test and ACT composite scores (Wood, Nemeth, & Brooks, 1985). Phonological Awareness. Phonological awareness was meas- ured using the Phoneme Detection Test administered via com- puter (Koo, Crain, LaSasso, & Eden, 2008). For this test, par- ticipants are instructed to determine whether a presented word includes the sound of the letter presented (e.g. Does it have a /k/?). Prior to beginning the test, each participant completes a set of four practice trials. Next, the participant is presented  M. D. CLARK ET AL. 111 individually with 30 high-frequency words with multiple or- thography-to-phonology correspondences, and is required to identify whether the targeted phoneme is included in each of the words. Responses were recorded by pressing 1 on the key- board if the word included the target phoneme or 2 if it did not have the target phoneme. Morphological Knowledge. The Guessing Game test was developed to evaluate deaf individuals’ ability to use morpho- logical knowledge when identifying words and their meanings. To test this question, both high and low frequency words (monomorphemic and multimorphemic words) were selected from Thorndike and Lorge’s (1972) The Teacher’s Word Book of 30,000 Words. Twenty-eight words were selected from Thorndike and Lorge: seven high frequency, monomorphemic words; seven high frequency, multimorphemic words; seven low frequency, monomorphemic words; and seven low fre- quency, multimorphemic words. Participants were presented with a worksheet in matching format, asked to pair the words with their definitions, and instructed to use their decoding strategies with novel words. The name “Guessing Game” was utilized to encourage participants to engage in the test, rather than to give up by saying that they did not know the words. Pilot testing demonstrated that using words with a frequency of one instance in a million were not decoded above chance levels within the general college population. Therefore, words with a frequency between 50 and 99 per million were selected. These changes lead to above chance responding in the second pilot test conducted with the new words. Participants Fifty deaf and hard-of-hearing participants were recruited for Study 1 by posting flyers at Gallaudet University. There were 19 men (mean age = 21.2 years) and 31 women (mean age = 21.1 years). Eighteen students were people of color, 29 were European Americans, and three students declined to report their race. With respect to English placement, 11 students were in Developmental English, 13 in Entry Level, 14 students in Ad- vanced, and 12 students in Honors. Two testing sessions were employed, leading to missing data on some tests. Procedure Participants were given both written instructions and ASL instructions about the purpose of the study. In addition, students were made aware that the study consisted of three components: the Guessing Game; the Phoneme Detection Test; and a back- ground questionnaire that queried their language background and previous school experience. Students took all three portions of the study after reading and signing an informed consent form. Results There were approximately equal numbers of participants in each of the four English placement levels, as reported above. Summary statistics for the Phoneme Detection Test, Guessing Game total number of words correct, Guessing Game total number of monomorphemic words correct, and Guessing Game total number of multimorphemic words correct can be seen in Table 1. One-way ANOVAs were performed to investigate the impact of English placement on phonological and morphological de- coding skills. Four dependent variables were investigated: per- cent correct on the Phoneme Detection Test, Guessing Game total number of words correct, Guessing Game total number of monomorphemic words correct, and Guessing Game total number of multimorphemic words correct. ANOVA results are listed in Table 2. Two of the four variables showed significant differences between levels of English placement. The total number of words correct on the Guessing Game was significantly related to English placement levels, F(3, 28) = 4.83, p = .008, r2 = .34. As seen in Table 3, LSD post-hocs indicated that students with Developmental English placement matched significantly fewer words to their definitions than did those with Honors English placement, p = .02. Additionally, participants with Entry Level placement scored significantly lower than those with either Advanced placement (p = .012) or Honors placement (p = .002). Additionally, the total number of correct monomorphemic words on the Guessing Game was significantly related to Eng- lish placement levels, F (3, 28) = 5.62; p = .004, r2 = .38). LSD post hocs revealed differences among the group means, with those in Developmental English scoring significantly lower than those in Honors English, p = .006. Participants with Entry Level placement were significantly lower than those with either Honors (p = .001) or Advanced levels of English placement (p = .014). The number of correct multimorphemic words on the Guess- ing Game was not significantly related to the English placement levels (p = .078), but the results were in the expected direction. More importantly, scores on the Phoneme Detection Test were not significantly related to variation in levels of English place- ment. Discussion Hypothesis 1 stated that Deaf students with higher English placement levels would exhibit increased morphological de- coding skills, demonstrated by higher levels of accuracy on the Guessing Game. The results of Study 1 support this hypothesis, Table 1. Descriptive statistics for Study 1. Measure Mean SD Range Phoneme Detection Test score 18.71 4.84 11-28 GG: Total Number of Words Correct 10.32 4.78 2-24 GG: Total Number of Multimorphe mic Words Correct 5.68 2.52 1-11 GG: Total Num ber of Monomorphemic Words Correct 4.63 2.72 1-14  M. D. CLARK ET AL. 112 Table 2. Summary of ANOVAs comparing levels of English placement levels on the phoneme det ection test and the Guessing Game. Sum of Squares df Mean Square F p Between Gr oups 794.167 3 264.722 0.811 0.494 Within Groups 15008.413 46 326.270 PDT: % Correct Total 15802.580 49 Between Gr oups 100.557 3 33.519 5.615 0.004 Within Groups 167.162 28 5.970 GG: Total Monomorphemic Correct Total 267.719 31 Between Gr oups 50.349 3 16.783 2.521 0.078 Within Groups 186.370 28 6.656 GG: Tot al Multimorphemic Correct Total 236.719 31 Between Gr oups 288.449 3 96.150 4.829 0.008 Within Groups 557.551 28 19.913 GG: Total Words W ords Correct Total 846.000 31 Table 3. Descriptive statistics for the Guessing Game, split by English place- ment level. English Placement n per group GG Total Correct GG Total Monomorphemic Correct Developmental 11 8.7 3.3 Entry Leve l 13 6.9 2.7 Advanced 14 12.4 5.6 Honors 12 14.8 7.3 with students in higher English placements exhibiting better Although word-decoding strategies did vary significantly with total number of words correct and total number of monomor- phemic words correct on the Guessing Game, the total number of multimorphemic words correct was not significantly related to English placement levels (p = .078). However it is important to note that this finding did approach a marginal level of sig- nificance; given the low statistical power in this project, it is possible that increasing the number of participants would make this finding significant. Another possible explanation for the lack of significance is that multimorphemic words were se- lected based on English norms. In English those words have a high frequency of use; however, English words do not map to ASL signs on a one-to-one basis. Hypothesis 2 stated that Deaf students with higher English placement levels would exhibit increased phonological decod- ing skills, demonstrated by higher levels of accuracy on a pho- nological awareness task. This hypothesis was not supported, as English placement levels were not related to scores on the Phoneme Detection Test. Two issues were identified among the current sample of participants with respect to the Phoneme Detection Test. First, the participants had a wide range of cor- rect responses, from three to 99 percent correct. Second, the response time to individual items was longer than normal when compared to hearing participants who have taken the test. This long response time suggests that participants understood the task, but struggled to identify which words included the target phoneme. Even though some of our participants demonstrated phonological awareness, this knowledge did not predict success in reading. Similar to Izzo’s (2002) finding, when comprehen- sion of English is required, phonological awareness did not relate to success f ul reading performance. Interestingly, students mentioned using signs as a means of decoding novel English words. The spontaneous report of “I don’t know a sign for that” occurred many times while collect- ing data. Based on these statements, it appears that knowledge of ASL may guide English decoding. Two groups of English users could be identified in the data, those who had used English for more than 15 years and only recently started using sign and those that reported using both English and ASL for more than 15 years. Separate analyses of these two groups found no difference in their phonological awareness. These groups were self-identified, therefore it is difficult to know their actual skills in either English or ASL. Recent work by Morford, Wilkinson, Villwock, Pinar, & Kroll (2011) found that many individuals who reported that they were skilled bilinguals did not demonstrate a balance in language skills when formally tested. Future work is planned to more carefully investigate the language background of participants to determine if this finding will apply to those whose first lan- guage is English in contrast to those who are truly bilingual. Given these findings, a second study was conducted to specifi- cally measure the interaction of ASL skills, English word flu- ency, morphological knowledge, and phonological awareness. Study 2 Research Question and Hypotheses The second portion of this study investigated the role of bi- lingual ASL/English abilities, morphological knowledge, and phonological awareness on deaf individuals’ ability to decode written English. Hypothesis 1: Deaf students with higher levels of bilingual ability will exhibit increased morphological decoding skills, demonstrated by higher levels of accuracy on a morphological word-decoding task. Hypothesis 2: Deaf students with higher levels of bilingual  M. D. CLARK ET AL. 113 ability will exhibit increased phonological decoding skills, demonstrated by higher levels of accuracy on a phonological awareness task. Method Measures Bilingual Abilities. The American Sign Language–Sentence Reproduction Test (ASL-SRT) was used to evaluate each par- ticipant’s ASL proficiency. Using an online video interface, the ASL-SRT presents participants with 36 ASL sentences signed by a native signer (Hauser, Paludneviciene, Supalla, & Bavelier, 2008). The participant is required to view each video clip and then reproduce the sentence exactly as it was presented. The participants’ reproduction is also recorded through the online video interface. These sentences progressively increase in length as well as syntactic, thematic, and morphemic complex- ity. Inter-rater reliability of the ASL-SRT has been reported to be r = .83, p < .01(Hauser et al.). Reading skills were measured using the Woodcock Johnson III Test of Achievement (WJ III ACH) Reading Fluency. This subtest requires participants to read and comprehend simple sentences rapidly. It contains 98 written English “yes/no” ques- tions. Raw scores from the WJ III ACH Reading Fluency Subtest and the ASL-SRT were transformed into a combined Bilingual Abilities score. These raw scores were converted first to z-scores and then transformed to T scores. Next, multiplying the two T scores together created a combined Bilingual Ability score. Phonological Awareness. Phonological awareness was again measured using the Phoneme Detection Test (PDT) adminis- tered via computer (Koo et al., 2008). For a detailed explana- tion of the PDT, refer to the Measures section in Study 1. Morphological Knowledge. The Guessing Game test was again used to evaluate deaf individuals’ ability to use morpho- logical knowledge when identifying words and their meanings. The same twenty-eight words were utilized from Thorndike and Lorge: seven high frequency, monomorphemic words; seven high frequency, multimorphemic words; seven low frequency, monomorphemic words; and seven low frequency, multimor- phemic words. Participants Fifty-one deaf and hard-of-hearing participants were re- cruited for Study 2 by posting flyers at Gallaudet University. There were 15 men (mean age = 20.3 years) and 36 women (mean age = 20.7 years). Twenty-two participants identified as people of color, while 29 identified as European American. Two participants reported mild hearing loss, 10 moderate, 16 severe, and 22 profoundly Deaf with one participant declining to report their hearing loss. With respect to language preference, 43 participants reported a preference for ASL, 7 for Spoken English, and 1 for both ASL and Spoken English. Procedure Participants were given written instructions and information about the purpose of the current study. In addition, students were made aware that the study consisted of five components: the WJ III ACH Reading Fluency subtest; the ASL-SRT; the Guessing Game; the Phoneme Detection Test; and a back- ground questionnaire that queried their language background and previous school experience. Students took all five portions of the study after reading and signing an informed consent form. Results Summary statistics for the WJ III ACH Reading Fluency subtest, ASL-SRT, Phoneme Detection Test, and Guessing Game are li s ted in Table 4. Pearson correlations indicated that the Bilingual Abilities score was significantly related to the Guessing Game total score, r = .34, p = .01, with greater bilingual abilities related to in- creased morphological knowledge. Moreover, the Bilingual Abilities score was significantly positively related to Guessing Game monomorphemic and multimorphemic words correct (r = .30, p = 0.03; r = .35, p = .01). However, the Bilingual Abilities score was not significantly correlated with the PDT, r = .10, suggesting little relationship between bilingual abilities and phonological awareness. It is also important to note that Deaf participants in the current study had significantly slower reaction time (mean = 1 755) on this measure than prior research with hearing participants (mean = 1 145 msec), t(50) = 4.97, p = .000. Less-skilled and more-skilled readers were compared on the PDT using an independent t-test to ascertain the contribution of phonological awareness on fluent reading ability. Results indi- cate less-skilled readers (i.e., those in the lowest tertile of all participants (10th grade level and below; n = 17)) and more- skilled readers (i.e., those in the top tertile (graduate level and above; n = 19)) did not perform significantly differently on the PDT, t(32) = –0.88, p = .39. However, it is important to note that the variability in phonological awareness differed between these groups. Indeed, the more-skilled readers showed greater variability in phonological awareness when compared to less- skilled readers, with interquartile ranges of 23.00 and 10.83, respectively. Discussion Hypothesis 1 predicted that Deaf students with higher levels of bilingual ability in ASL and English would exhibit increased morphological decoding skills. This hypothesis was supported by the results of Study 2, as shown by the strong positive cor- relations between the measure of morphological knowledge and the Bilingual Abilities variable. Hypothesis 2 predicted that Deaf students with higher levels of bilingual ability would ex- hibit increased phonological decoding skills. This hypothesis was not supported, as shown by the non-significant correlation between the measure of phonological awareness and the Bilin- gual Abilities variable. It was also observed that Deaf individu- als required significantly more time to respond to items on the phonological awareness task when compared to past research Table 4. Descriptive statistics for Study 2. Measure Mean Range WJ III ACH Reading Fluency: Grade Equivalent 13.13 4.4-18.8 ASL-SRT: Total Score 23.55 7-33 Guessing Gam e: Total Score 11.7 2-22 PDT: Perce nt Correct 58.8 0-89.3  M. D. CLARK ET AL. 114 on hearing subjects, suggesting that deaf individuals may ap- proach the task differently than their hearing peers. Moreover, less-skilled and more-skilled readers did not show any significant difference in their ability to use phonological knowledge, with the 50th percentile of both groups scoring at chance levels. While there was no significant difference in phonological awareness between reading skill levels, Deaf in- dividuals showed variability in their scores of phonological awareness, with less-skilled readers exhibiting a smaller range of phonological abilities compared to more-skilled readers. The greater variability of scores in the more-skilled reading group allowed for more participants in this group to demonstrate phonological awareness. Some of the more-skilled readers ex- hibited high levels of phonological awareness. General Discussion Results from these studies do not support the link between phonological awareness, reading, and decoding skills in “real life” situations across the deaf population. However, the results do show that some deaf students are able to perform tasks that require phonological knowledge and therefore support prior research suggesting that deaf students do have phonological awareness (Conrad, 1979; Hanson, 1982; Hanson, Liberman & Shankweiler, 1984; Hanson & Lichtenstein, 1990; Harris & Moreno, 2006; Krakow & Hanson, 1985). One possible expla- nation of these results is the findings of Mayberry et al.’s (2011) meta-analysis where when phonological awareness was re- ported in previous studies, it explained less than 15% of the variance. This effect size suggests that one can find statistical significance but not practical significance. In this line, Koo et al. (2008) found that both deaf individuals who use cued speech and those who label themselves as oral deaf showed phonological awareness on the PDT. These find- ings were in contrast to the Koo et al. deaf participants who were signers and did not show an effect of phonological awareness of the PDT. It is important to note that all of Koo et al.’s participants were skilled readers as determined by a screening evaluation. Therefore, the findings from the current study, as well as those from Koo et al., suggest that there are multiple pathways that deaf readers take to become skilled readers. Despite hypotheses that higher reading levels correlate to better phonological awareness skills (Paul et al., 2009), the current study did not find support for this idea. Even though phonological awareness has not been found to be sufficient for a deaf person to become a skilled reader (see Allen et al., 2009), many still hold that phonology is necessary to become a skilled reader (Paul et al., 2009). Alternative pathways are suggested by recent findings on ASL/English bilingualism that have found that native signing of ASL significantly predicted bilingual abilities in ASL and written English, implying that having control of ASL as a na- tive language may act as a bridge to stronger reading abilities (Freel, Clark, Anderson, Gilbert, Musyoka, & Hauser, 2011). Previous research conducted by Vernon and Koh (1970), Strong and Prinz (1997), and Stuckless and Birch (1966) showed that deaf children of deaf parents perform significantly better on reading comprehension tests than deaf children of hearing parents. Therefore, deaf children of deaf parents, who are raised in an ASL environment and develop ASL as a native language, have been found to possess stronger reading skills than deaf children raised by hearing parents, who do not de- velop ASL as a native language. Freel et al.’s work supports the idea that establishing ASL as a complete first language can foster enhanced literacy in written English as a second language. Similarly, Allen, Hwang, and Stansky (2009) found that deaf individuals’ ASL scores explained 68% of the variance in reading scores. The current study, as well as Izzo (2002), suggests that for tasks requiring comprehension and decoding skills, visual strategies lead to more effective results. Here it appears that phonological awareness may develop as a result of effective English reading abilities. Future work with young deaf readers can help determine if this progression–from more visually based morphographic knowledge to later phonological knowl- edge–occurs for these readers. Both logographic and orthor- graphic information is fully accessible to young deaf learners and would help scaffold ASL knowledge to printed English. Later, familiarity with the printed English words could help build phonological skills. Further research is warranted to in- vestigate the use of ASL as a first language as a means for sec- ond-language a c q uisition. Clearly, this work is focused on a sample of deaf individuals who are bilingual. As such, it cannot explore all possible path- ways that are used by deaf people to become skilled readers. Even so, the current study suggests a ‘Yes’ response to the Paul et al. (2009) question: “Are there skilled deaf readers for whom phonological coding is a rarely used skill?” (p. 348). In terms of, “Why is this the case?”, one can only propose that it was not found to be a necessary or helpful route to reading. With re- gards to “difference[s] between skilled and unskilled deaf read- ers,” these results suggest that some deaf skilled and unskilled readers DO develop phonological awareness. This finding may be linked to their early language choices, as some of the par- ticipants in these studies acquired ASL later in life. Regardless, one can identify both skilled and unskilled deaf readers, with and without, phonological awareness. Future research needs to more clearly evaluate why this is the case. On the other hand, it is possible that younger deaf readers do rely on phonological information and the alphabetic principle, a finding that was not captured with the current sample of college students. Current research is investigating this question in young children aged three to five years to further clarify these issues. In conclusion, it appears that phonological awareness is not necessary for the development of deaf individuals’ English reading skills and that many deaf individuals utilize morpho- logical strategies that provide direct access to meaning. These results, in conjunction with that of Freel et al. (2011) and Allen et al. (2009), suggest that Deaf students with higher levels of bilingual ability in ASL and English exhibit increased morpho- logical decoding skills. Aligning with this work, Gaustad (2000) emphasized the use of visual strategies as a means of learning to read in what is termed the morphological reading approach. Here the focus is geared toward the development of vocabulary and text comprehension with the general goal of increasing metacognitive and metalinguistic skills. Therefore, as suggested by Gaustad, morphographic analysis could be used as an effec- tive strategy in the classroom when teaching young deaf readers how to “break the code” of English.  M. D. CLARK ET AL. 115 Acknowledgements The following undergraduates were involved in data collec- tion; Jason Begue, Brianne Weber, Jonathan Penny, Amanda Krieger, Vivienne Schroeder. In addition, Selina Agyen, the Database Manager of VL2 was also involved in data collection and data management. We would also like to thank the partici- pants for their time and effort. References Allen, T. (1986). Patterns of academic achievement among hearing impaired students: 1974-1983. In A. Schildroth & M. Karchmer (Eds.), Deaf Children in America (pp. 161-206). San Diego, CA: Lit- tle, Brown. Allen, T. E., Clark, M. D., del Giudice, A., Koo, D., Lieberman, A., Mayberry, R., & Miller, P. (2009). Phonology and reading: A re- sponse to Wang, Trezek, Luckner, and Paul. American Annals of the Deaf, 145, 338-345. doi:10.1353/aad.0.0109 Allen, T. E., Hwang, Y., & Stansky, A. (2009). Measuring factors that predict deaf students’ reading abilities: The VL2 Toolkit-Project de- sign and early findings. An nu al M ee ti ng of t he Association of College Educators of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing , New Orleans. Charlier, B. L., & Leybaert, J. (2000). The rhyming skills of deaf chil- dren educated with phonetically augmented speechreading. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 53, 349-375. doi:10.1080/027249800390529 Colin, S., Magnan, A., Ecalle, J., & Leybaert, J. (2007). Relation be- tween deaf children’s phonological skills in kindergarten and word recognition performance in first grade. The Journal of Child Psy- chology and Psychiatry, 48, 139-146. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01700.x Conrad, R. (1979). The deaf school child: Language and cognitive function. London: Harper Row. Department of Program Services – Student Assessment Office. (2003). Degrees of reading power (DRP) interpretation guide. Retrieved from www.schoolimprovement.ocps.net/studentassessment/docs/DRP%20 Interpretation%20Guide.doc Dyer, A., MacSweeney, M., Szczerbinski, M., Green, L., & Campbell, R. (2003). Predictors of reading delay in Deaf adolescents: The rela- tive contributions of rapid automatized naming speed and phono- logical awareness and decoding. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 8, 215-229. doi:10.1093/deafed/eng012 Ehri, L. (1992). Reconceptualizing the development of sight word reading and its relationship to recoding. In P. Gough, L. Ehri, & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading acquisition (pp. 107-143). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Ehri, L., Nunes, R. S., Stahl, S., & Willows, D. (2001b). Systematic phonics instruction helps students learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis. Review of Educational Re- search, 71, 393-447. doi:10.3102/00346543071003393 Freel, B. L., Clark, M. D., Anderson, M. L ., Gilbert , G. L., Musyoka , M. M., & Hauser, P. C. (2011). Deaf individuals’ bilingual abilities: American Sign Language proficiency, reading skills, and family characteristics. Psychology, 2, 18-23. doi:10.4236/psych.2011.21003 Frith, U. (1985). Beneath the surface of developmental dyslexia. In K. Patterson, J. Marshall, & M. Coltheart (Eds.), Surface dyslexia: Neurological and cognitive studies of phonological reading (pp. 301- 330). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Frost, R. (1998). Toward a strong phonological theory of visual word recognition: True issues and false trails. Psychological Bulletin, 123, 71-99. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.123.1.71 Gaustad, M. (2000). Morphographic analysis as a word identification strategy for deaf readers. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Educa- tion, 5, 61-80. doi:10.1093/deafed/5.1.60 Hanson, V. L. (1982). Short-term recall by deaf signers of American Sign Language: Implications for order recall. Journal of Experimen- tal Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Recognition, 8, 572-583. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.8.6.572 Hanson, V. L., & Fowler, C. A. (1987). Phonological coding in word reading: Evidence from hearing and deaf readers. Memory and Cog- nition, 15, 199-207. doi:10.3758/BF03197717 Hanson, V. L., Liberman, I. Y., & Shankweiler, D. (1984). Linguistic coding by deaf children in relation to beginning reading success. Journal of Experimental Child Psycho logy, 37, 378-393. doi:10.1016/0022-0965(84)90010-9 Hanson, V. L., & Lichtenstein, E. H. (1990). Short-term memory cod- ing by deaf signers: The primary language coding hypothesis recon- sidered. Cognitive Psychology, 22, 211-224. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(90)90016-W Hanson, V. L., & McGarr, N. S. (1989). Rhyme generation by deaf adults. Journal of Speech and Hearing Resea r c h , 3 2, 2-11. Harris, M., & Moreno, C. (2006). Speech reading and learning to read: A comparison of 8-year-old profoundly Deaf children with good and poor reading ability. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11, 189-201. doi:10.1093/deafed/enj021 Hauser, P., Paludneviciene, R., Supalla, T., & Bavelier, D. (2008). American Sign Language–Sentence Reproduction Test: Develop- ment & implications. In R.M. de Quadros (Ed.), Sign languages: Spinning and unraveling the past, present and future (pp. 160-172). Petrópolis, Brazil: Editora Arara Azul. Hulme, C., Snowling, M., Caravolas, M., & Carroll, J. (2005). Phono- logical skills are (probably) one cause of success in learning to read: A comment on Castles and Coltheart. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9, 351-365. doi:10.1207/s1532799xssr0904_2 Izzo, A. (2002). Phonemic awareness and reading ability: An investiga- tion with young readers who are deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, 147, 18-28. Kelly, L. P., & Barac-Cikoja, D. (2007). The comprehension of skilled deaf readers: The roles of word recognition and other potentially critical aspects of competence. In K. Cain & J. Oakhill (Eds.), Chil- dren’s comprehension problems in oral and written language (pp. 244-280). New York: The Guilford Press. Koo, D., Crain, K., LaSasso, C., & Eden, G. (2008). Phonological awareness and short-term memory in hearing and deaf individuals of deaf individuals of different communication backgrounds. Annals of the New York Academy o f Science, 1145, 83-99. doi:10.1196/annals.1416.025 Krakow, R. A., & Hanson, V. L. (1985). Deaf signers and serial recall for visual modality: Memory for signs, fingerspelling, and print. Memory and Cognition, 13, 265-272. doi:10.3758/BF03197689 Leybaert, J., & Alegria, J. (1993). Is word processing involuntary in deaf children? British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 11, 1-29. Luetke-Stahlman, B., & Nielsen, D. C. (2003). The contribution of phonological awareness and receptive and expressive English to the reading ability of deaf students with varying degrees of exposure to accurate English. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 8, 464-484. doi:10.1093/deafed/eng028 Marschark, M., & Harris, M. (1996). Success and failure in learning to read: The special case of deaf children. In C. Coronoldi & J. Oakhill (Eds.), Reading comprehension difficulties: Process and intervention (pp. 279-300). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Marslen-Wilson, W., Komisarjevsky, T., Waksler, R., & Older, L. (1994). Morphology and meaning in the English mental lexicon. Psy- chology Review, 101, 3-33. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.101.1.3 Mayberry, R. I., del Guidice, A. A., & Lieberman, A. M. (2011). Read- ing achievement in relation to phonological coding and awareness in deaf readers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 16, 164-188. doi:10.1093/deafed/enq049 Miller, P. (1997). The effect of communication mode on the develop- ment of phonemic awareness in prelingually deaf students. Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research, 40, 1151-1163. Miller, P. (2005a). Reading comprehension and its relation to the qual-  M. D. CLARK ET AL. 116 ity of functional hearing: Evidence from readers with different func- tional hearing abilities. American Annals of th e D ea f, 150, 305-323. doi:10.1353/aad.2005.0031 Miller, P. (2006a). What the word recognition skills of prelingually deafened readers tell about their reading comprehension problems. Journal of Development and Physical Disabiliti es, 18, 91-121. doi:10.1007/s10882-006-9002-z Miller, P. (2006b). What the processing of real words and pseudo- homophones tell about the development of orthographic knowledge in prelingually deafened individuals. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11, 21-38. doi:10.1093/deafed/enj001 Miller, P. (2007a). The role of phonology in the word decoding skills of poor readers: Evidence from individuals with prelingual deafness or diagnosed dyslexia. Journal of Developmental and Physical Dis- abilities, 19, 385-408. doi:10.1007/s10882-007-9057-5 Miller, P., & Clark, M. D. (in press). Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilites. Morford, J. P., Wilkinson, E., Villwock, A., Pinar, P., & Kroll, J. F. (2011). When deaf signers read English: Do written words activate their sign translations? Cognition, 118, 286-292. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2010.11.006 Musselman, C. (2000). How do deaf children who can’t hear learn to read an alphabetic script? A review of the literature on reading and deafness. Journal of Deaf S tu d i es and Deaf Education, 5, 11-31. doi:10.1093/deafed/5.1.9 Narr, R. F. (2008). Phonological awareness and decoding in deaf/ hard-of-hearing students who use Visual Phonics. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 13, 405-416. doi:10.1093/deafed/enm064 Paul, P. V., Wang, Y., Trezek, B. J., & Luckner, J. L. (2009). Phonology is necessary, but not sufficient: A rejoinder. American Annals of the Deaf, 154, 346-356. doi:10.1353/aad.0.0110 Perfetti, C. A., & Sandak, R. (2000). Reading optimally builds on spo- ken language: Implications for deaf readers. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 5, 32-50. doi:10.1093/deafed/5.1.32 Report of the National Reading Panel (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Schirmer, B. R., & Williams, C. (2003). Approaches to teaching read- ing. In M. Marschark & P.E. Spencer (Eds.), Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education (pp. 110-122). New York: Oxford University Press. Share, D. L. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: Sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55, 151-218. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(94)00645-2 Share, D. L. (2004). Orthographic learning at a glance: On the time course and developmental onset of self-teaching. Journal of Experi- mental Child Psychology, 87, 267-298. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2004.01.001 Share, D. L. (2008). On the anglocentricities of current reading research and practice: The perils of overreliance on an “outlier” orthography. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 584-615. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.584 Shaywitz, S. E., & Shaywitz B. A. (2005). Dyslexia (specific reading disability). Biological Psychiatry, 57, 1301-1309. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.043 Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academic Press. Strong, M., & Prinz, P. M. (1997). A study of the relationship between American Sign Language and English literacy. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 2, 37-46. Stuckless, E. R., & Birch, J. W. (1966). The influence of early manual communication on the linguistic development of deaf children. American Annals of the Deaf, 142, 71-79. Sutcliffe, A., Dowker, A., & Campbell, R. (1999). Deaf children’s spelling: Does it show sensitivity to phonology? Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 4, 111-123. doi:10.1093/deafed/4.2.111 Thorndike, E. L., & Lorge, I. (1972). The teacher’s word book of 30,000 words. New York: Teachers College Press. Transler, C., Leybaert, J., & Gombert, J. (2005). Do deaf children use phonological syllables as reading units? Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 4, 124-143. doi:10.1093/deafed/4.2.124 Troia, G. (2004). Phonological processing and its influence on literacy learning. In C. Stone, E. Silliman, B. Ehren, & K. Appel (Eds.), Handbook of language and literacy: Development and disorders (pp. 271-301). New York: The Guilford Press. Vellutino, F. R., Fletcher, J. M., Snowling, M. J., & Scanlon, D. M. (2004). Specific reading disability (dyslexia): What have we learned in the past four decades? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychia- try, 45, 2-40. doi:10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00305.x Vernon, M., & Koh, S. D. (1970). Early manual communication and deaf children’s achievement. American Annals of the Deaf, 115, 527-536. Wang, Y., Trezek, B. J., Luckner, J., & Paul, P. V. (2008). The role of phonology and phonologically related skills in reading instruction for students who are deaf or hard of hearing. American Annals of the Deaf, 153, 396-407. doi:10.1353/aad.0.0061 Wood, P. H., Nemeth, J. S., & Brooks, C. C. (1985). Criterion-related validity of the Degrees of Reading Power Test (Form CP-1A). Edu- cational and Psychological Measurement, 45, 965-969. doi:10.1177/0013164485454030

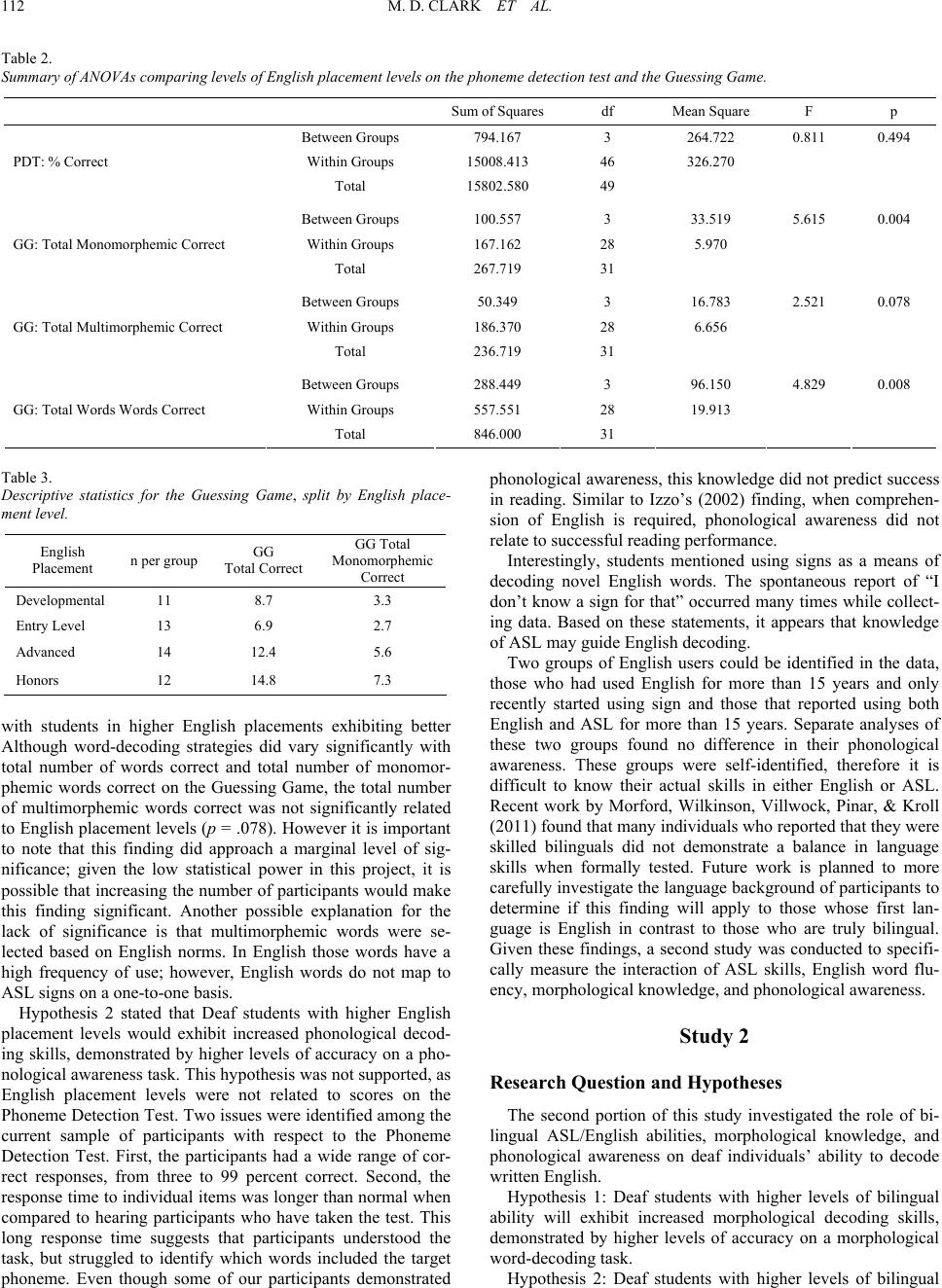

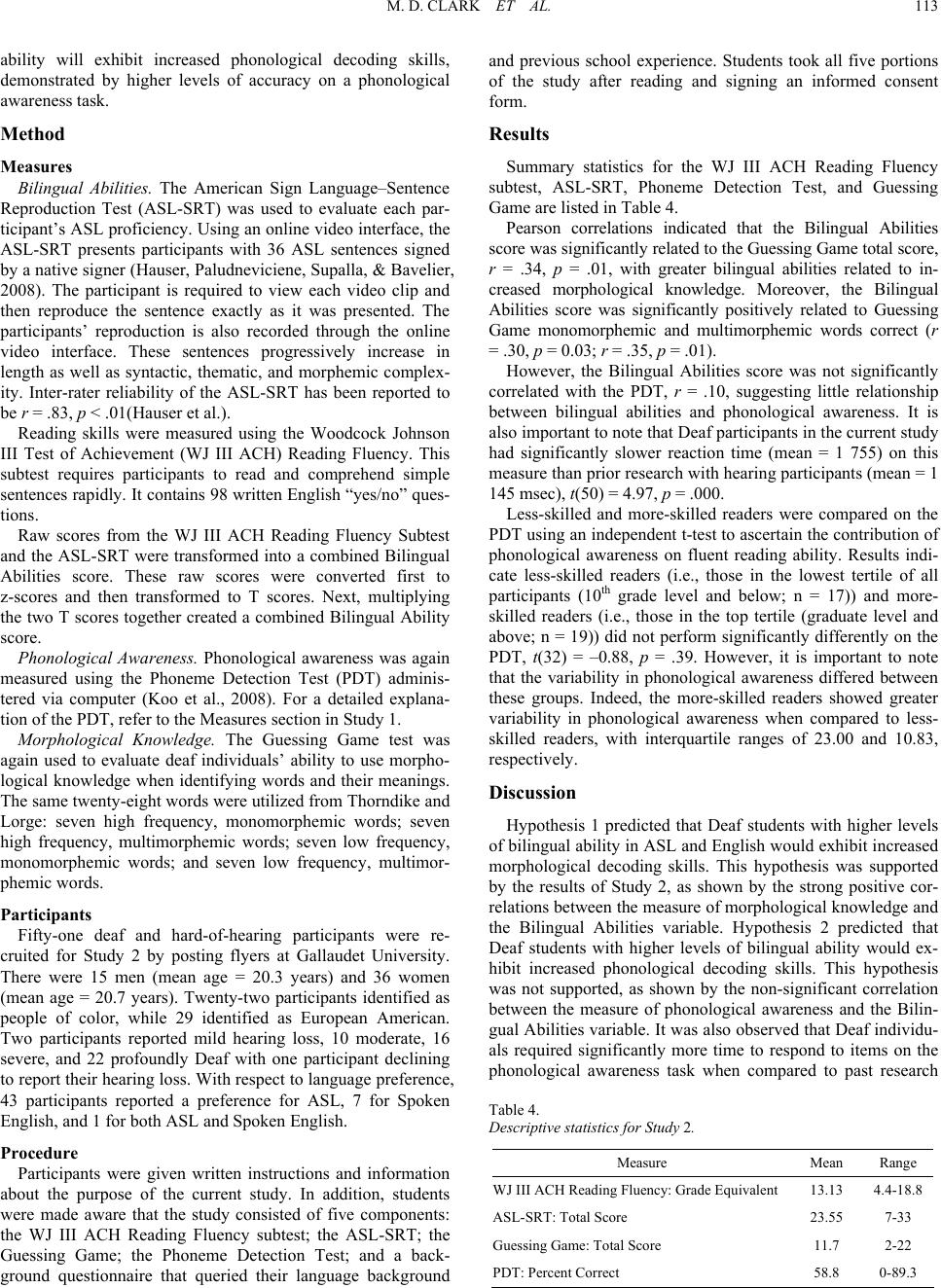

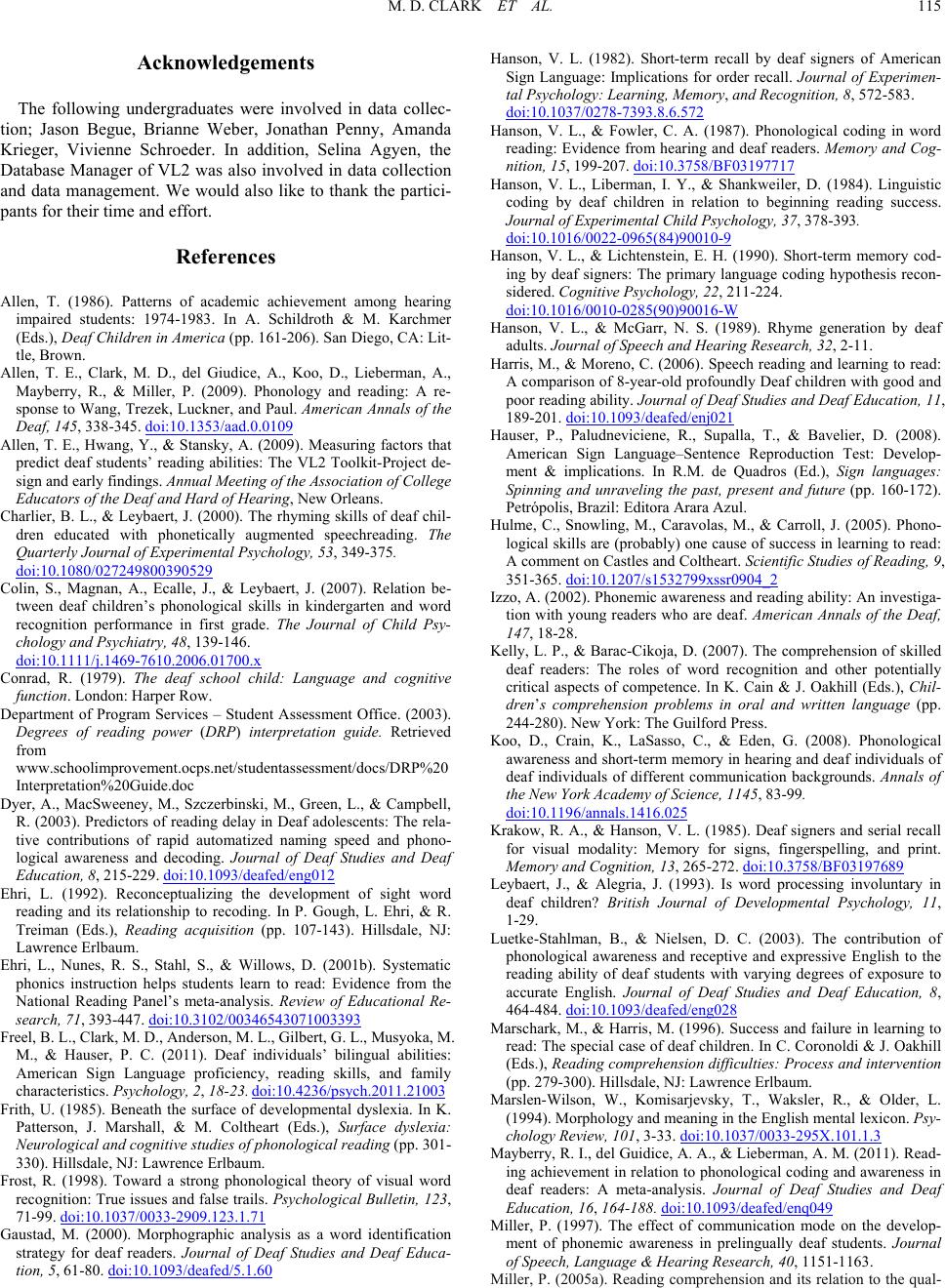

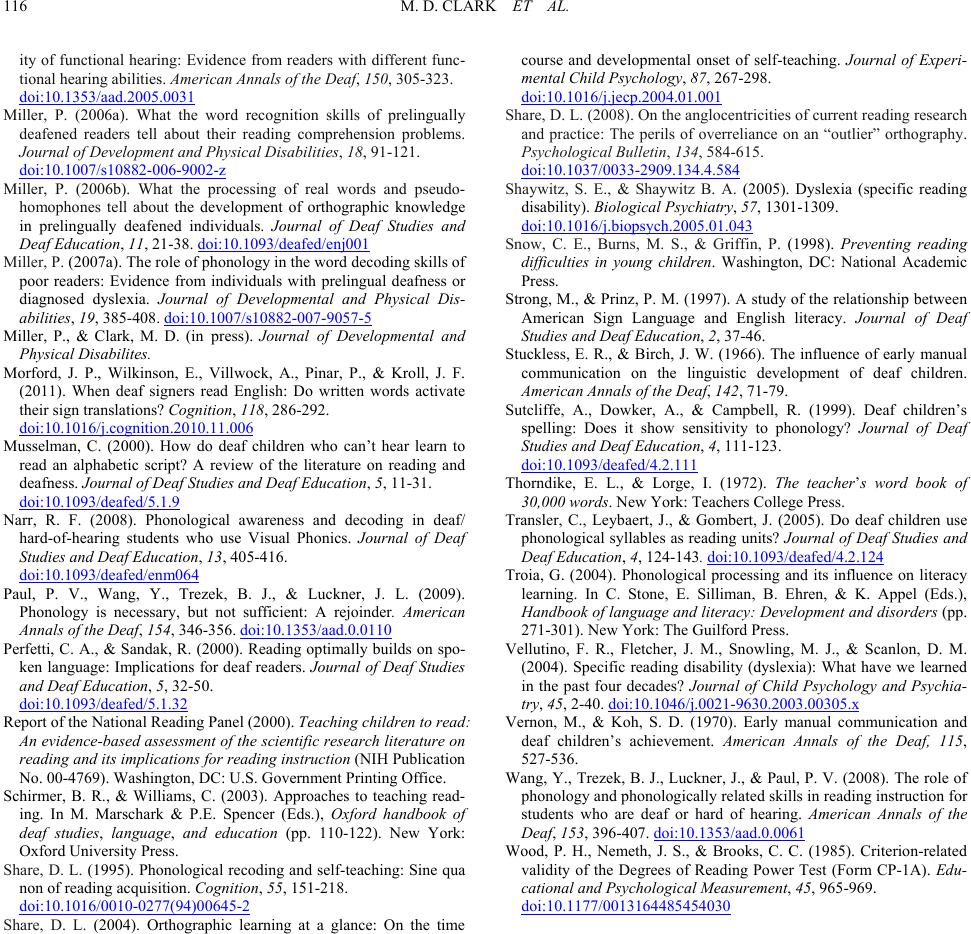

|