Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.2, 63-70 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.22011 Self-Construal and Subjective Wellbeing in Two Ethnic Communities in Singapore Weining C. Chang1, Mohd Maliki Bin Osman2, Eddie M. W. Tong3, Daphne Tan3 1Division of Psychology, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; 2Member of the Parliament, Republic of Singapore, Singapore; 3Department of Psychology, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: weiningc@ntu.edu.sg Received October 13th, 2010; revised December 23rd, 2010; accepted December 30th, 2010. The study reported here addressed two questions concerning the applicability to other collectivist cultures of a model developed on the basis of socially defined self-construals and their consequences for subjective wellbeing (Kwan, Bond, & Singelis, 1997). In contrast to the social centrality of the Singaporean Chinese, Islam enjoys centrality in the Malay community. Is subjective well-being in these two cultures attributable to independent or interdependent self-construal? Do parallel paths to subjective wellbeing originate from these two forms of self-construal? Are the respective mediators, self-esteem and relationship harmony, functioning in the same way in these different communities? Two hundred and eighty-six participants (121 Malays, including 49 females and 72 males, and 165 Chinese, including 62 males and 103 females, average age, 18.52) were drawn from three ter- tiary technical training institutes in Singapore. Independent and interdependent self-construal, Rosenberg’s Self-esteem Scale (SE), the Relationship Harmony Scale (RH) (Kwan, et al. 1997) and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SL) (Diener, Emmons. Larsen, & Griffins, 1985) were administered to test the model. For the Chinese, the best-fit model required a path between the two forms of self-construal, confirming their overlapping nature. For the Malays, a radically different model fits the data: relationship harmony no longer functions as a mediator but as an independent contributor in its own right. These results raise questions about the meaning and conse- quences of socially defined self-construal in different collectivist cultures, and the path between the self and subjective wellbeing. Keywords: Subjective Wellbeing, Culture, Self, Chinese, Malays Introduction Subjective wellbeing has been the focus of intense research attention (Diener, 1984; Leung & Leung, 1992; Diener & Die- ner, 1995). Recent cross-cultural research has provided pre- liminary evidence for culture-specific correlates of life satisfac- tion (for instance, Diener & Diener, 1995). Specifically, Kwan, Bond and Singelis (1997) found that there are two conceptually coherent and psychologically meaningful routes to life satisfac- tion traceable to independent and interdependent self-construal. Independent self-construal reaches life satisfaction through mediation by individual self-esteem, while interdependent self-construal reaches life satisfaction through mediation by relationship harmony. These conclusions are acceptable if one allows the assumption that the independent and the interde- pendent variables are 1) orthogonal to each other and are 2) discrete constructs. In other words, there are no psychological overlaps between these two construals of the self. In cultures where such assumptions cannot be met does the model still hold? In terms of the mediating variables, this model relies on the assumptions that 3a) individual self-esteem is conceptually and psychologically related to the independent self construal and 3b) relationship harmony is conceptually and psychologi- cally related to interdependent self-construal. Could these as- sumptions be met in other collectivist cultures? Cross-culturally, relationship harmony and individual self- esteem are both important for Chinese and Americans in terms of life satisfaction, but the mediation effect of relationship harmony on life satisfaction is greater, for instance, in Hong Kong than in the United States (Kwan et al., 1997). This result was interpreted in terms of the greater importance of interde- pendent self-construal in Hong Kong, a Chinese community and presumably collectivist, than in the United States, which is presumably less collectivist. What might be the role of the self, especially the culturally conditioned constructs of the self, in the individual’s life-satisfaction or subjective wellbeing in an- other Asian collectivist context remains to be investigated. It is our contention that collectivism is not the only dimension of cultures in Asia. In different Asian cultures, though they are mostly collectivist, there are other dimensions of culture that might interact with the social emphasis of collectivism to pro- vide different meanings and consequences of socially defined self-construal. The culture of the Chinese is a socio-centric culture where interpersonal relationships play a central role in a person’s daily life (Huang, 1999). Though social interdepend- ence is a shared feature of many Asian cultures, some Asian cultures structure themselves on the basis of religious beliefs, such as the Muslims in many different countries in Asia. Can their life satisfaction be explained by a model constructed on the notion of human relationships? Singapore has a Chinese majority (76%) but has a substantial Malay minority (12%). Both the Malays and the Chinese in Singapore have collectivist cultures (Chang, in press). There is both divergence and similarity between these two ethnic groups.  W. C. CHANG ET AL. 64 In terms of cultural heritage, Singaporean Malays derive their emphasis on the collective from the traditional cultures of the indigenous Malay and Islam (Zarina, Isnis, & Chang, 2003); the Chinese derive their emphasis on the collective from Con- fucianism or its popular modern forms (Chang, Wong, & Koh, 2003). It can be hypothesized that the differences and similari- ties between these two cultures would lead to differences and similarities in their self-construal and life satisfaction. Our past studies have found that in Singapore, instead of forming two discrete constructs, independent and interdepend- ent self-construal overlap when measured as individual differ- ences of disposition variables. In daily social interactions, the manifestation of the two forms of self construal in Singaporean Chinese form a continuum from independence to increasing interdependence according to the level of intimacy that the person has with the other person (Chang, 2001). Much less is known about the self-construal of Malays. Malay cultural heri- tage has two distinct features: 1) traditional indigenous Malay culture that emphasizes the interdependence between the self and social others, and 2) Islam, where God is the creator of all things including the self. Within this religion-centric culture, the self might take on additional meaning compared to the so- cially defined independent and interdependent self. The indi- vidual’s life satisfaction is often attributed to one’s belief in God (Shahiraa & Chang, 2004). Within this context, what im- portance and what roles do the mediating variables, individual self-esteem and relationship harmony, play in providing life satisfaction? Is the model, based on the dichotomy of inde- pendent and interdependent self construal, applicable to cul- tures where the two forms of construal might overlap? What might be the nature of the self-construal and its consequences in a collectivist but highly religious culture? Pathways to Life Satisfaction: Self-Construal, Self-Esteem an d R el a tionship Harmony In terms of the self and collectivist cultures, Kwan et al. (1997) have shown that self-esteem and relationship harmony mediate the relationship between self-construal (SC) and sub- jective wellbeing (SWB). Relationship harmony was found to be a mediator between interdependent self-construal and sub- jective wellbeing. This path is logical and psychologically meaningful only when the assumption that relationship har- mony is derived from interdependent self-construal is met. In Singapore, independent and interdependent self-construal have been found to be positively correlated with each other (Tong, Chang, & Koh, 2003). In our preliminary research on the predictors of self-esteem, we also found that relationship harmony is an important contributor to Singaporeans’ feelings of self-esteem (Tong et al., 2003). That relationship suggests that the individual’s self esteem might be drawn from both independent and interdependent self-construal in this predomi- nantly Chinese community. This finding of the intertwined nature of the two forms of self-construal and their relationships with relationship harmony and self-esteem further cast doubt on the applicability of the Kwan model in Singapore. In cultures where religion has a central role, such as that of the Malays in Singapore, and where the self and the psycho- logical constructs related to the self such as self-esteem and self-other relationships are seen to be God-given, (Brenner, 1996; Shahiraa & Chang, 2003), what might the relationship be between self-construal and the individual’s life satisfaction? Hypothesizing different relationships between these predic- tors of subjective wellbeing in different collectivist cultures, we tested the Kwan model separately within two samples (i.e., Chinese and Malays) in Singapore. Attention was specifically focused on the internal structure of self-construal in the Chinese and the Malay communities. Method Participants Participants were drawn from three polytechnic institutes in Singapore with a stratified random sampling method to derive two matching samples of Malays and Chinese. As Malays con- stitute only 12% of the general population, they were over- sampled, whereas the Chinese, constituting 76% of the popula- tion, were under-sampled. Two hundred and eighty six students from three polytechnics and one technological-training institute participated in the study. They comprised 165 Chinese (62 males and 103 females) and 121 Malays (49 males and 72 fe- males). The mean age of the participants was 18.52 (SD = 1.73). Measures The 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE S: Rosenberg, 1965) was used to assess global self-esteem (SE). The partici- pants responded to each item on a 5-point scale ranging from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree). The Cronbach alphas for the overall sample, Chinese sample and Malay sam- ple were .75, .77, and .72 respectively. The Interpersonal Relationship Harmony Inventory (IRHI: Kwan & Bond, 1996) was used to assess perceived relationship harmony (RH). Participants were instructed to think (for about 5 minutes) of five different dyadic relationships and to rate each of these relationships on four items. For the first two items, participants indicated the nature of the relationship (e.g. father, friend) and the gender of the target in the relationship. The last two items asked for the participant’s rating of the relationship in terms of perceived degree of harmony and the contributions of the relationship to one’s happiness on a 4-point scale ranging from “1” (very low) to “4” (high). A relationshi p harmony index for each participant was computed by multiplying the harmony score of each relationship with its contribution-to-happiness score and then summing the resulting values across the five relationships. Singelis’s (1994) Self-Construal Scale (SCS) was employed to assess the extent of interdependent and independent SC. Twelve items in the SCS were designed to measure interde- pendent self-construal and another 12 to measure independent self-construal. Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed (or did not agree) with each of the items on a 5-point scale that ranged from “1” (strongly disagree) to “2” (strongly agree). For independent SC, the alpha values for the overall sample, Chinese, and Malays were .65 each. For interdependent SC, the internal reliabilities for the whole sample and the Chi- nese were .53 and .71, respectively. However, one item (#16) “I am comfortable being singled out for praise or rewards” had to be removed from the Malay data to achieve an acceptable reli- ability of .63. It is our understanding that within Malay culture,  W. C. CHANG ET AL. 65 being humble is an important virtue; this item was considered inappropriate by many Malays. Perception of satisfaction with one’s life was assessed by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS: Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). Participants responded on a 5-point scale ranging from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree) on each of the five items that measured the extent to which they were satisfied with their lives (e.g. “I am satisfied with my life”). Previous studies had demonstrated strong reliabilities and convergence validity of the SWLS (c.f., Larsen, Diener, & Emmons, 1985; Pavot & Diener, 1993). In this study, the alpha value the overall sample was 0.73, while those of the Chinese and Malays were 0.75 and 0.69 respectively. Procedure The participants completed a questionnaire that contained the abovementioned scales arranged in random order. Permission to conduct the study in the four institutions was given by their respective administrative departments. The student participation was voluntary and anonymous. All participants were carefully briefed by the researchers about completing the questionnaires and the confidentiality of the replies. The participants were also assured of anonymity in their responses. No difficulties in answering the questionnaires were reported; each session took approximately 30 minutes. Results Preliminary Analysis Descriptive Data Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of the seven variables examined. One clear result is that the scores for Malays on these variables were higher than those of the Chi- nese; t-tests on each variable verified that the Malays were significantly higher than the Chinese on every variable. How- ever, any conclusion of real ethnic difference at this point is unwarranted because there is the possibility of culturally based response bias, or response mode (Van de Vijver & Leung, 1997). We thus de signed a way to adjust for this potential bias. Assuming that the differential response bias is evenly dis- tributed across measures of all psychological constructs, we constructed a correction term (Chang, 2003) by averaging the between-group differences of all items of all measures used in the study. The between-group difference of each construct was the tested against this grand mean difference. With this analysis, we found that none of the between-group differences reached statistical significance. Independent and Interdepe nde nt Se lf-Construal in Singapore Submitting the 24 items of the SCS to factor analysis with varimax rotation, we found an acceptable structure, as pre- sented in Table 2, with the interdependent and independent items meaningfully loaded onto two factors. However, as we predicted, the inter-factor correlation is very high, –0.592, sug- gesting that in Singapore these two forms of self-construal are not independent of each other but are highly overlapping with the interdependent self more salient than the independent self. Similar results were obtained when the analysis was repeated with each of the ethnic groups. We again tested the two factor structures by constraining the solution to two factors. As can be seen in Table 2, the items fell into the two meaningful groups of Factor 1 - Interdependent Self-construal, and Factor 2 - In- dependent Self-construal. However, the two factors accounted for only 24.59%and 24.56% of the total variance for the Chi- nese and the Malay data, respectively. What is striking about this result is the highly intertwined nature of these two factors. For the Malays and the Chinese, the inter-factor correlations are –0.566, and –0.576, respectively. These results suggested that although the independent and interdependent dichotomy might not be most applicable to self-construal, the exact nature of self-construal in different Asian communities might be more complicated than the two-way division. More importantly, the independent and in- terdependent forms of self construal were highly inter-related in both ethnic samples. They are certainly not discrete variables but are continuations of each other: that is, the relationship between the independent and the interdependent aspects of the self might be interdependent or reciprocal. This would have implications in the psychological consequences predicted by these forms of self-construal (Chang, 2001). Subjective Wellbeing (SWB) The results of factor analyses reveal a one-factor solution for the overall sample, the Chinese, and the Malays, accounting for 49.8%, 51.9%, and 45.6% of the respective data. Thus, it ap- pears that the factor structure for SWB is replicated among our samples. Zero-Order Correlations Table 3 presents the correlations among the variables. Across the two ethnic groups, SWB positively correlated with the four predictor variables. The strongest association was found be- tween SWB and SE, consistent with research showing that self-esteem is a strong predictor of life satisfaction (Diener, 1984; Diener & Di e n e r , 1995 ) . However, more interestingly, RH correlated almost as highly as SE with SWB. This is consistent with the findings among Hong Kong participants in the Kwan et al. (1997) study show- ing that in a collectivistic culture like that of the current sample, RH is as strong a predictor of SWB as SE. Furthermore, con- sistent with previous findings (Singelis, Bond, Lai, & Sharkey, Table 1. Means and standard deviations of five variables in the overall sample, Chinese, and Malays. Chinese Malay Total M SD M SD M SD Subjective Wellbeing 15.283.57 16.34 3.28 15.733.48 Self-esteem 32.965.15 34.17 5.01 33.475.12 Relationship Harmony 77.7024.9588.80 20.52 82.3023.81 Independent Self-construal 3.49 0.42 3.51 0.43 3.69 0.41 Interdependent Self-construal 3.61 0.43 3.85 0.70 3.73 0.53 a . Calculated as per item mean.  W. C. CHANG ET AL. 66 Table 2. Factor structure of Singaporea n se l f-construal. Factor 1 2 Variable Whole ChineseMalay Whole ChineseMalay 6. I will sacrifice my self-i nterest for the benefit of the group. 0.656 0.487 0.68 5. I respect p eople who are modest about themselves. 0.573 0.437 0.616 9. It is important to me to respect decisions made b y the group. 0.561 0.504 0.7 3. My happiness depends on the happiness of those around me. 0.545 0.566 0.551 10. I will stay in a group if they need me, even when I am not happy with the group. 0.545 0.463 0.51 7. I often have the fee li ng th at my relationships w i th others are more important than my own. 0.526 0.453 0.632 2. It is important for me to maintain harmony w it hin my group. 0.483 0.521 0.495 4. I would of f er my seat in a bus to my prof essor. 0.475 0.437 0.448 1. I have res pect for the authority figures with whom I interact. 0.46 0.616 0.265 12. Even when I stron gly disagre e with group members I avoid argum ents. 0.319 0.201 0.325 8. I should take into consideration my parents’ advice when making educa- tion/ career plans. 0.237 0.46 0.239 14. Speaki n g up during class is not a problem for me. 0.61 0.592 0.653 19. I act the same way no matter who I am with. 0.55 0.49 0.62 21. I prefer to be direct and forth r ight when dealing wit h p eople. 0.544 0.573 0.579 22. I enjoy be ing unique and different from others in many respects. 0.504 0.526 0.407 17. I am the same person at home and at school. 0.482 0.404 0.533 23. My personal identity indepe n dent of others is very im por tant. 0.421 0.316 0.304 13. I’d rather say “no” directly, t han risk bein g misunderstood. 0.41 0.476 0.336 18. Being abl e to take care of myself is a primary concern for me. 0.404 0.35 0.376 16. I am comfortable with being singled out for praise or rewards. 0.403 0.542 0.222 20. I feel comfortable u si ng someone’s first name soon after I meet t he m even when they are much older than I am. 0.342 0.328 0.476 15. Having a lively imagination is important to me. 0.328 0.358 0.311 24. I value being in good health above everything. 0.309 0.148 0.458 11. If my brot her or sister fa i ls, I feel r esponsible. 0.198 0.12 0.234 1995), SE correlated with independent SC but not with inter- dependent SC. However, RH correlated positively with both independent and interdependent SC in our sample, which is similar to what Kwan et al. (1997) found in their Hong Kong sample. The lower two sections of Table 3 present the inter-correla- tions among the 5 variables according to the ethnic groups. For the Chinese, SWB was positively correlated with SE, RH, and interdependent SC. Again, both SE and RH were equally strong predictors of SWB. Interestingly, among the Chinese, SE not only correlated positively with independent SC, but also with interdependent SC. RH was positively associated with both SCs. For the Malays, SWB correlated positively with all variables except interdependent SC. In fact, the interdependent SC of the Malays only correlated with independent SC, and not with any other variables included in this model. Main Analysis We first tested the applicability of the Kwan, et al. (1997) model to the Singaporean context. Then we sought to delineate a model that would best fit Singapore. To this end, we first performed a series of mediation analyses procedures outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) to deduce the pathways leading from each form of self-construal to SWB. In doing so, we were not only able to test the mediation process proposed by Kwan et al. (1997) (see Figure 1), but also determine whether there could be “cross-mediation”: that is, whether RH and SE also  W. C. CHANG ET AL. 67 Table 3. Intercorrelations between five variables in the overall sample, Chinese, and Malays. 1 2 3 4 5 Overall Subjective Wellbeing Self-Esteem 0.33** Relationship-Harmony 0.31**0.23** Independe nt Self-con strual 0.15**0.37** 0.30** Interdepe ndent Self -c ons trua l 0 . 13 *0 . 10 0.24** 0.27** Chinese Subjective Wellbeing Self-Esteem 0.38** Relationshi p Harmony 0.31**0.29** Independe nt Self-con strual 0.11 0.34** 0.37** Interdepe ndent Self -c ons trua l 0.25**0. 19 * 0.33** 0.27** Malay Subjective Wellbeing Self-esteem 0.23* Relationship Harmony 0.23*0.08 Independe nt Self-construal 0.18*0.38** 0.17 Interdepe nde nt Sel f -cons t rual 0.00 0.01 0.13 0.27** ** p < .01 ; * p < .05 0.37 0.28 0.23 Independent Self-construal Interdependent Self-construal Self Esteem Relationship Harmony Subjective Wellbeing 0.24 All path coefficients are significant at p = .05. Figure 1. The Kwan et al. model. mediate the effect on SWB by independent SC and interdepend- ent SC respectively. This procedure allowed us to construct a model that may provide a more precise explanation of our data. Section 1: Fitting of the Kwan et al. model. The result of the analysis revealed only a moderate fit of the Kwan, et al. model to the data of the overall sample. 2 (5) = 25.75, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.12, GFI = 0.97, NFI = 0.84, CFI = 0.86, and IFI = 0.86. The fit was good but not excellent because of the rela- tively large RMSEA. Chinese. The same analysis was conducted on the Chinese sample. Again the results showed a poor fit of the Kwan, et al. model to the Chinese data: 2 (5) = 29.10, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.17, GFI = 0.94, NFI = 0.74, CFI = 0.76, and IFI = 0.77. The fit was good but not excellent due to the relatively large RMSEA. Malays. In contrast, when the data for the Malays were tested, the results revealed an excellent fit, 2 (5) = 5.59, p = .35, RMSEA = 0.032, GFI = 0.98, NFI = 0.89, CFI = 0.99, and IFI = 0.99. However, the path between interdependent SC and relationship harmony was non-significant. Additional analysis. We further tested this ethnic difference by using the multi-sample option in LISREL that allows com- parison of models across independent groups. Consistent with the foregoing results, this test revealed a poor fit, 2 (19) = 63.76.10, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.091, GFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.66, CFI = 0.73, and IFI = 0.73. This indicated that the Kwan et al. (1997) model failed to fit the two samples equally well. Section 2: In search of a Singaporean model - mediation analysis. Kwan et al. (1997) argued that the relationship be- tween independent SC and SWB and that between interde- pendent SC and SWB were mediated by SE and RH, respec- tively. We sought to extend this argument by testing the extent to which the relationship of SWB with each form of SC was mediated by both SE and RH. Thus, we performed a series of mediation analyses. We first investigated the extent to which the effect of independent SC on SWB is mediated by both SE and RH. Subsequently we performed the same test on the rela- tionship between interdependent SC and SWB. We performed four sets of mediation analyses. The first two analyses pertained to the effect of independent SC (the predic- tor) on SWB (the criterion), one analysis examined the mediat- ing role of SE, and one examined that of RH. The next two sets of analyses pertained to the effect of interdependent SC (the predictor) on SWB as mediated by SE and SH. Independent SC on SWB. As can be seen in Table 3, SWB was significantly associated with independent SC. Additionally, SWB was significantly related to SE. As the two pre-requisites of mediation analysis were met, SWB was regressed simulta- neously onto independent SC and SE. The relationship between independent SC and life satisfaction was reduced to being non-significant, = .03, t (286) = 0.56, p > .05, whereas SE remained a significant predictor, = .32, t (286) = 5.33, p < .01, thus demonstrating a total mediation. The procedure was re- peated with RH as the mediator. The relationship between in- dependent SC, and SWB became non-significant, = .07, t (286) = 1.21, p > .05, while that between RH and SWB was significant, = .26, t (286) = 4.38, p < .01, once again demon- strating total mediation. Thus, the relationship between inde- pendent SC and SWB in Singapore is not only totally mediated by SE as sho wn by Kwan et al. (1997), but is also mediated by RH. In our sample an individual’s self-esteem (SE) and their relationship harmony (RH) were closely intertwined. Interdependent SC on SWB. The procedure was then re- peated with the relationship between interdependent SC and SWB. First, as can be seen in Table 3, interdependent SC was related to SWB, thus fulfilling the first prerequisite of media- tion analysis. Interdependent SC was associated with RH but not SE. This indicates that only RH could serve as the mediator of the relationship between interdependent SC and SWB. Thus, SWB was regressed simultaneously onto interdependent SC and RH. The results revealed a total mediation of RH between interdependent SC and SWB because RH remained a signifi- cant predictor of SWB, = .27, t (286) = 4.63, p < .01, whereas when RH was partialled out, interdependent SC no longer pre- dicted SWB, = .08, t (286) = 1.31, p ns. Hence, this series of  W. C. CHANG ET AL. 68 mediation analyses showed that it was RH, and not SE, that served as the mediator between interdependent SC and SWB. The Singapore model. The combined results of this series of mediation analyses thus suggested a model that might better fit the data from Singapore. This model is presented on Figure 2. This model is similar to that of Kwan et al., (1997) in that the relationship between interdependent SC and SWB was medi- ated by RH. However, it is different from that of Kwan et al., (1997) in certain key issues: our analyses revealed that the ef- fect of independent SC on SWB was not only mediated by SE, but also by RH. Testing the Singaporean model. Further testing of the Sin- gaporean model indicated that it fit the data well: 2 (4) = 6.98, p = .14, RMSEA = 0.005, GFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.98, and IFI = 0.98.1 We tested whether our model differed signifi- cantly from the Kwan et al. model; this comparison yielded the following results: 2 = 18.77, df = 1, p < .001. Hence, taken together, the Singaporean model constructed through mediation analysis fitted the data better than the Kwan et al. (1997) model. Section 3: Ethnicity specific models. We repeated the series of analyses used in Section 2 on the two ethnic samples sepa- rately with the newly identified Singaporean model. The results showed that data of the two groups cannot be equally fit by the Singaporean model: 2 (18) = 44.44, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.072, GFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.84, and IFI = 0.84. This suggested the possibility that the data obtained from these two ethnic groups might be best described by ethnicity specific models. Chinese model. We first consider a specifically Chinese model. Mediation analysis: independent SC on SWB. As seen in Ta- ble 3, independent SC did not show significant correlation with SWB for the Chinese data. No mediation analysis was con- ducted for the effect of independent SC on SWB. Mediation analysis: interdependent SC on SWB. As the sec- ond section of Table 2 shows, interdependent SC was signifi- cantly associated with SWB, SE, and RH. Following this, we simultaneously regressed SWB onto SE and interdependent SC. The results indicate partial mediation because, although SE predicted SWB, = .35, t (165) = 4.76, p < .01, the effect of interdependent SC on SWB was reduced but remained signifi- cant, = .19, t (165) = 2.56, p < .05. Similarly, we regressed SWB onto interdependent SC and RH to test for any mediating effect of RH. In this case, RH totally mediated the relationship between interdependent SC and SWB, because it remained a significant predictor of SWB, = .28, t (165) = 3.31, p < .001, while the effect of interde- pendent SC on SWB was reduced to non-significance, = .11, t (165) = 1.31, p ns. Structural equation modeling. Therefore, mediation analysis suggests a Chinese model in which the relationship between interdependent SC and SWB was mediated by both SE and RH. Submitting this model to SEM yielded an inadequate fit to the data, 2 (2) = 14.46, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.20, GFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.80, CFI = 0.81, and IFI = 0.82 and modification indices suggested an additional pathway connecting SE and RH. Fur- ther analysis was conducted to determine the causal direction between SE and RH. We regressed SWB onto both RH and SE. The results show that while the relationship between SWB and SE was not reduced, = .38, t (145) = 5.02, p < .001, the rela- tionship between SWB and RH was substantially reduced, while remaining significant, = .20, t (145) = 2.61, p = .01. This suggests a stronger path from RH to SE than from SE to RH. Following this, we derived the Chinese model as shown in Figure 3. SEM testing revealed a good fit of the model to the data: 2 (1) = 3.63, p = .57, RMSEA = 0.13, GFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.95, CFI = 0.96, and IFI = 0.96. The best fit model and stan- dardized path coe ffi cients are present ed in Figu re 2. Malay model. A Malay model can also be derived from the mediation analysis. Mediation analysis: independent SC on SWB. Table 2 indi- cates that independent SC predicts SWB and SE but not RH. We regressed SWB ont o inde pendent SC and SE simultaneou sly . The relationship between SE and SWB remained, = .19, t (119) = 2.01, p < .05, whereas the effect of independent SC on SWB was reduced to non-significance, = .12, t (119) = 1.10, p ns. Mediation analysis: interdependent SC on SWB. As Table 3 indicates, interdependent SC did not show significant correla- tion with SWB in the Malay sample. Thus mediation analysis was not carried out. RH, however, showed significant correla- tion with SWB, suggesting an independent contribution of RH to SWB. Structural equation modeling. The Malay model derived from the mediation analysis is one whereby independent SC is the only form of self-construal that predicts SWB via the me- diation effect of SE. In addition, as RH also correlated with SWB, we included a path from RH to SWB. The resulting pat- tern is shown in Figure 4. Subjecting this model to SEM, it provided an excellent fit to the data: 2 (2) = 0.63, p = .73, RMSEA = 0.00, GFI = 1.00, NFI = 0.98, CFI = 1.00, and IFI = 1.04.3 This model is more parsimonious than the Kwan et al. (1997) model, to which the Malay data also fit. In comparing the two models, it was found that they did not differ significantly 0.37 0.18 0.28 0.23 Independent Self-Construal Interdependent Self-Construal Self Esteem Relationship Harmony Subjective Wellbeing 0.25 0.27 All path coefficients are significant at p = .05. Figure 2. Path coefficients for Singaporean model. 0.32 0.32 0.20 Independent Self-Construal Interdependent Self-Construal Self Esteem Relationship Harmo n Subjective Wellbeing 0.18 0.34 0.27 All path coefficients are significant at p = .05. Figure 3. The Singaporean Chinese model .  W. C. CHANG ET AL. 69 0.27 0.38 0.22 0.20 Independent Self-Construal Interdependent Self-Construal Self Esteem Relationship Harmon Subjective Wellbeing All path coefficients are significant at p = .05. Figure 4. The Singaporean Malay model. from each other, 2 = 4.96, df = 3, p ns. Thus, the simpler model as illustrated in Figure 4 was identified as the Malay Model. Discussion We set out to ask whether a model of subjective wellbeing developed within one collectivist culture is applicable to other collectivist cultures in Asia, in this case Singaporeans and the Chinese and Malay subgroups therein. These are groups whose culture(s) overlap with that of the Hong Kong Chinese in terms of collectivism - the emphasis on the collective and interper- sonal relationships. Singaporean Malays are 99% Muslim. Their religious belief to a great extent provides the basic worldview on which to construct their self-construal, and their view of interpersonal relationships and subjective wellbeing. We found that although self-esteem and relationship harmony were significant contributors to life satisfaction, the relation- ships between the predictors, independent and interdependent self-construal, and the mediator variables, self-esteem and rela- tionship harmony, seem to work differently in different ethnic groups. Relationsh ip b e tw e e n Independent and Interdependent Self-Construal To begin with, independent and interdependent self-construal were found to be positively correlated to a significant extent for the entire Singapore sample and for the Malays and the Chinese separately. This indicates that the two forms of self-construal might not be clearly separable in terms of their impacts on the criterion measures. More importantly, the intertwining might mean that they could be two sides of the same construct in these Asian communities (Tong, Chang, & Koh, 2003) rather than psychologically separate constructs. Seen in this light, the fol- lowing results will be logically explicable. Self-Esteem an d R el a tionship Harmony The two variables, hypothesized to mediate the two forms of self-construal and subjective wellbeing, were positively corre- lated to each other in the entire sample, and in the Chinese sample, but not in the Malay sample. We will discuss this result separately for each ethnic group. For the Chinese, individual self-esteem does not exist independently of relationship har- mony. This conclusion is in line with the traditional Chinese belief that the individual’s self-esteem is derived from, and is conferred to, the individual by people who are related to the self. For the Malays, relationship harmony seemed to be independent of individual self-esteem, and was also curiously independent of the interdependent self-construal. Interdependent self-construal in the Malays was correlated with neither self-esteem nor rela- tionship harmony. The SEM analysis of interdependent self-construal was not found to contribute to the subjective wellbeing of the Malays. This is a surprise to us. The Malays as a community place high emphasis on the collective and inter- personal relationships. However, being Muslim, they also be- lieve in God and attribute life events mostly to God (Brenner, 1996; Shahiraa & Chang, 2003). Under the influence of Islam, Malays in Southeast Asia have been observed to construct their self-concepts on the basis of religion rather than social rela- tionships (Brenner, 1996). This religious orientation might suggest that independent/interdependent self-construal dichot- omy might not capture the shared beliefs and meaning of the self within the Malay Muslim community. More studies need to be conducted to identify the conceptualization and manifesta- tion of the self within the Malay community before conclusions can be drawn about the two forms of self-construal and their psychological c onsequences. Predicting Subjective Wellbeing Our study has extended the conclusions drawn by Kwan et al. (1997) in that we have identified that the two mediators, self-esteem and relationship harmony, work differently within different Asian ethnic groups. Both self-esteem and relationship harmony are important mediators of subjective wellbeing, but in the Singaporean sample they were intertwined and did not operate independently of each other. This intertwining might be due to the equally intertwined nature of independent and inter- dependent self-construal in the Singaporean context. The general Singapore context is one with a high emphasis on the collective and interpersonal harmony, but within each ethnic group, the shared emphasis on the collective - or collec- tivism-might take on different institutional and behavioral forms. Collectivism, or interdependence, in the Chinese and the Malay cultures of Singapore might originate from different cultural heritages; for the Chinese, relationships constitute the fundamental core of their world view, while for the Malays, relationships are God-given and thus independent of construals of the self. These differences could lead to differences in many self-related psychological processes and constructs, including subjective wellbeing and the paths that lead to subjective well- being. References Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The Moderator-Mediator vari- able distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strate- gic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 Chang, W. C. (2003). Correction for differential response bias for be- tween group comparison. Research Note, Asian Cultural Psychology Project, National University of Singapore. Chang, W. C. (2001, April). Multifaceted Chinese self. Paper presented at the 59th Nebraska Symposium of Motivation, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska . Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satis-  W. C. CHANG ET AL. 70 faction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol- ogy, 68, 653-663. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.653 Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46, 71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 Huang, L. L. (1999). Harmony and conflict of interpersonal relation- ships: Indigenized theorization and research (in Chinese). Taipei, Taiwan: Laurate Books. Kwan, S. Y., Bond, M. H., & Singelis, T. M. (1997). Pancultural ex- planations for life satisfaction: Adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 1038- 1051. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1038 Larsen, R. J., Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). An evaluation of subjective well-being measures. Social Indicators Research, 17, 1-18. doi:10.1007/BF00354108 Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implica- tions for cognition, emotion and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224 Mohammad, N. B., Mohammad, I. B., & Chang, W. C. (2003). Stress- and-coping of Malay children in Singapore. Paper presented at the 5th International Conference of the Asian Association of Social Psy- chology, Manila, Philippines. Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment , 5, 164-172. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164 Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Shahiraa, Binte, M., & Chang, W. C. (2004). Stress-and-coping in the Malay organizational context. Working paper, Singapore: Center of Asian Cultural Psychology , Nanyang Technological University. Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interde- pendent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 580-591. doi:10.1177/0146167294205014 Singelis, T. M., Bond, M. H., Sharkey, W. F. & Lai, C. S. Y. (1999). Unpacking culture’s influence on self-esteem and embarrassability. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 315-341. doi:10.1177/0022022199030003003 Tong, E. M. W., Chang, W. C., & Koh, J. B. K. J. (2003). Differential psychological functioning based on the orthogonality of self-con- struals. Manuscript under review, Asian Cultural Psychology Project, National University of Singapore.

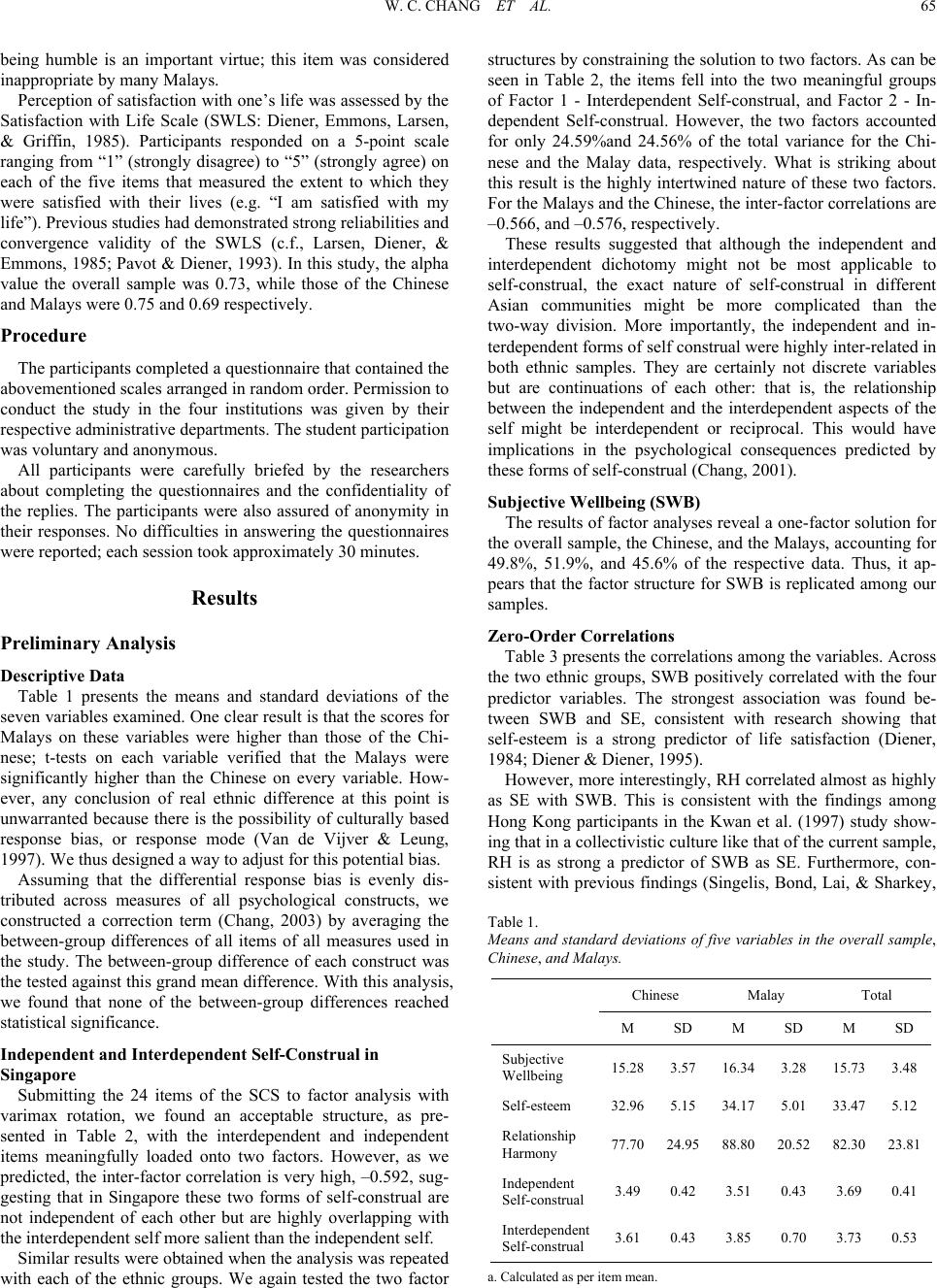

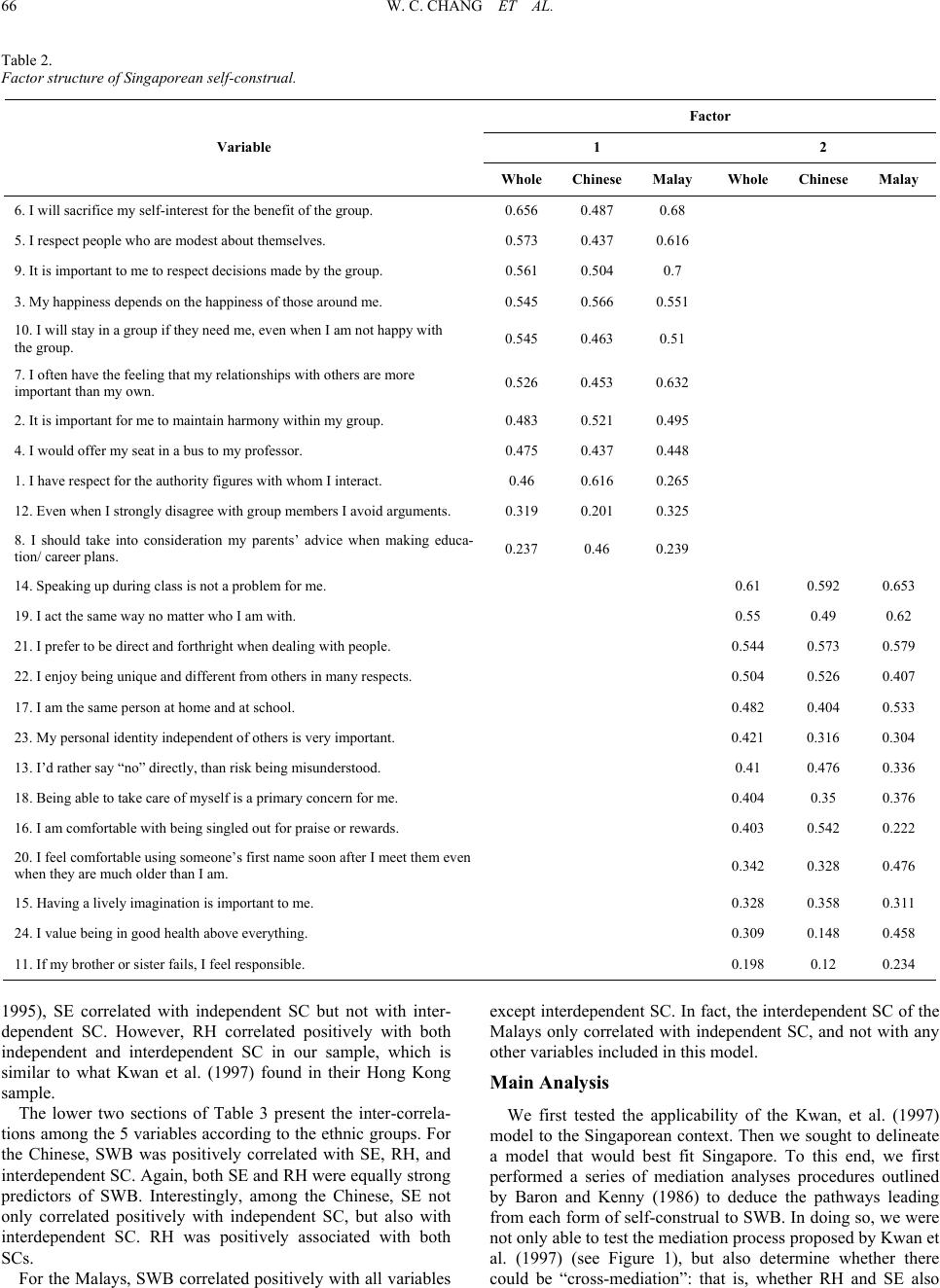

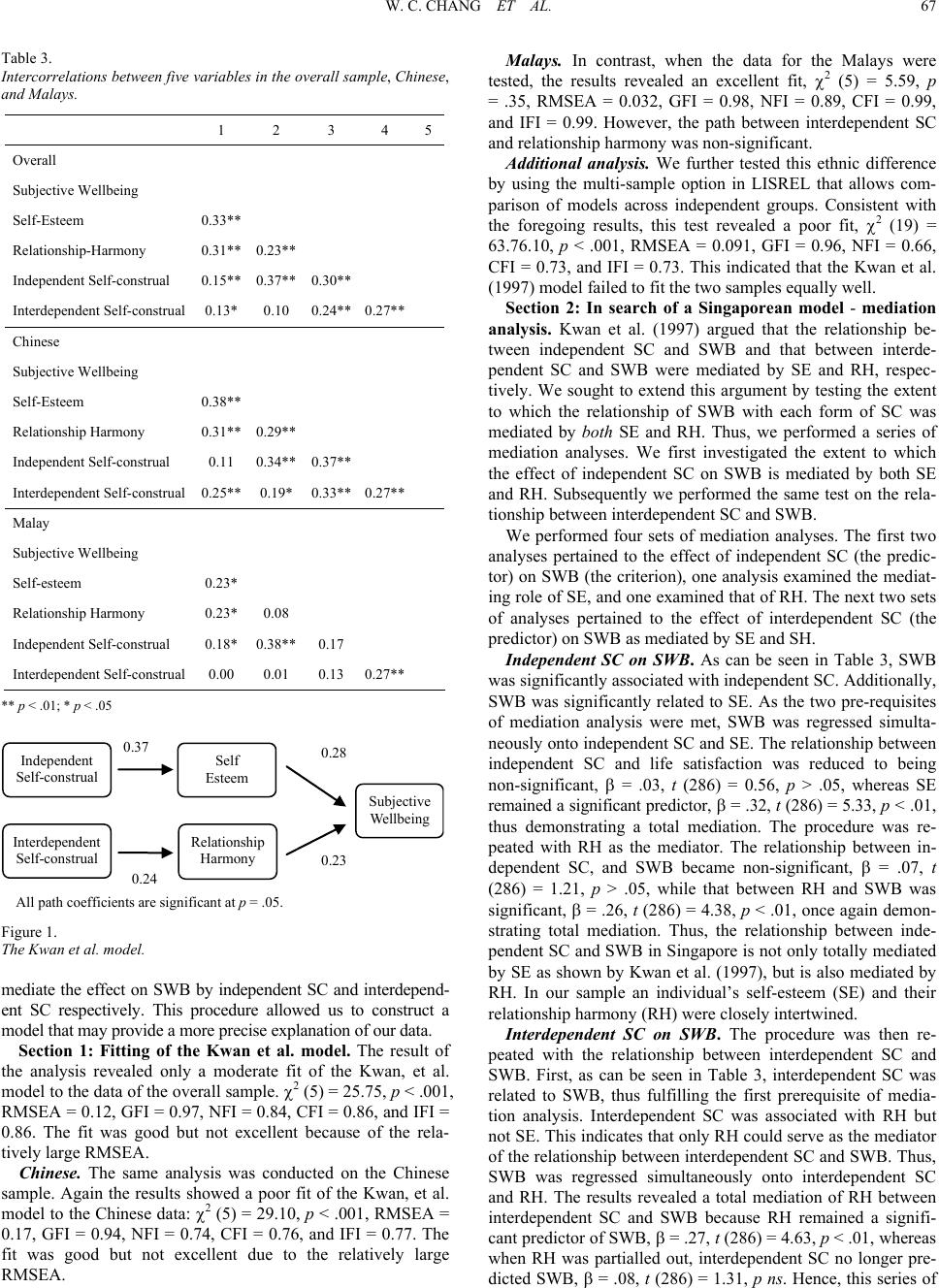

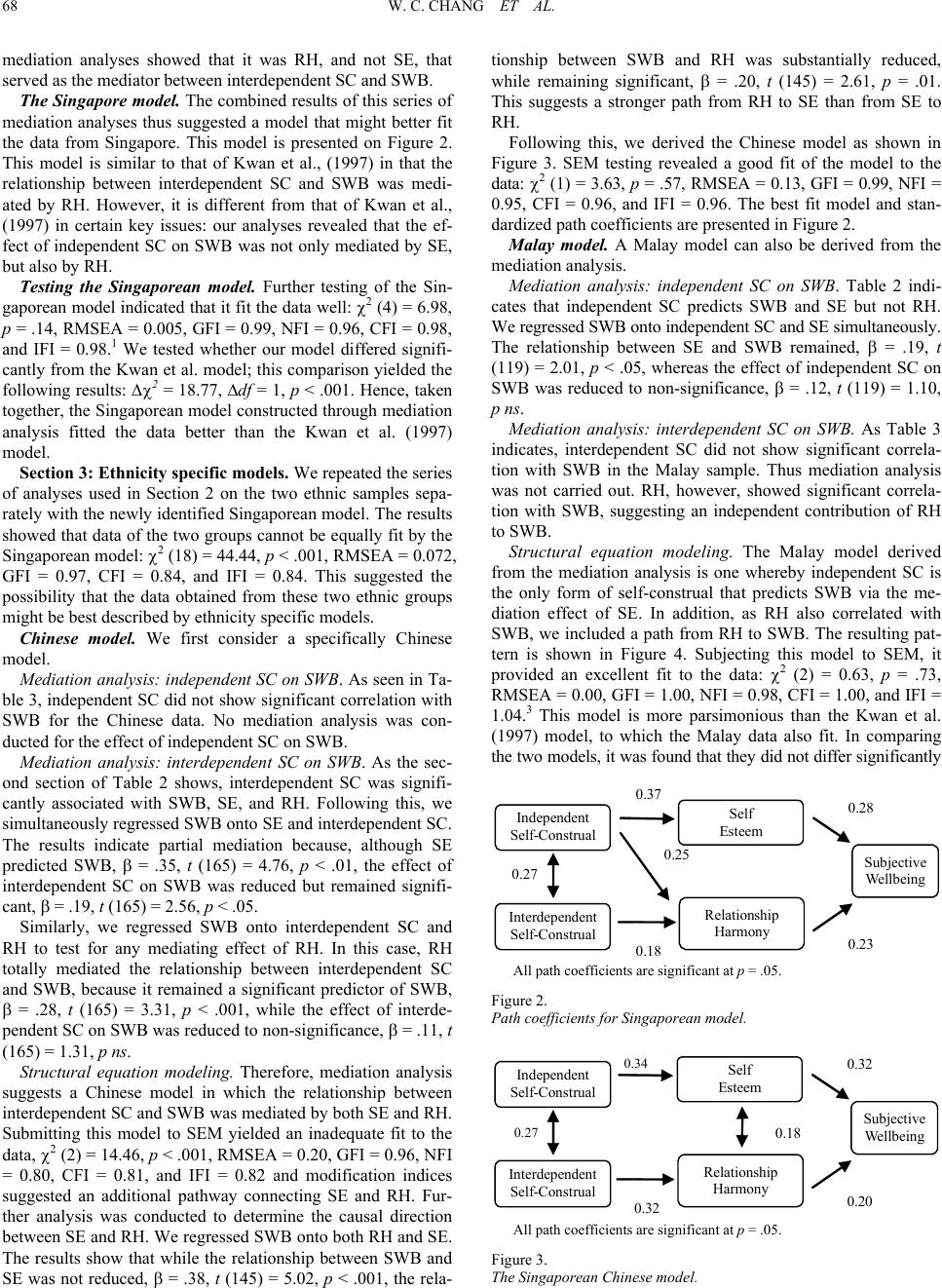

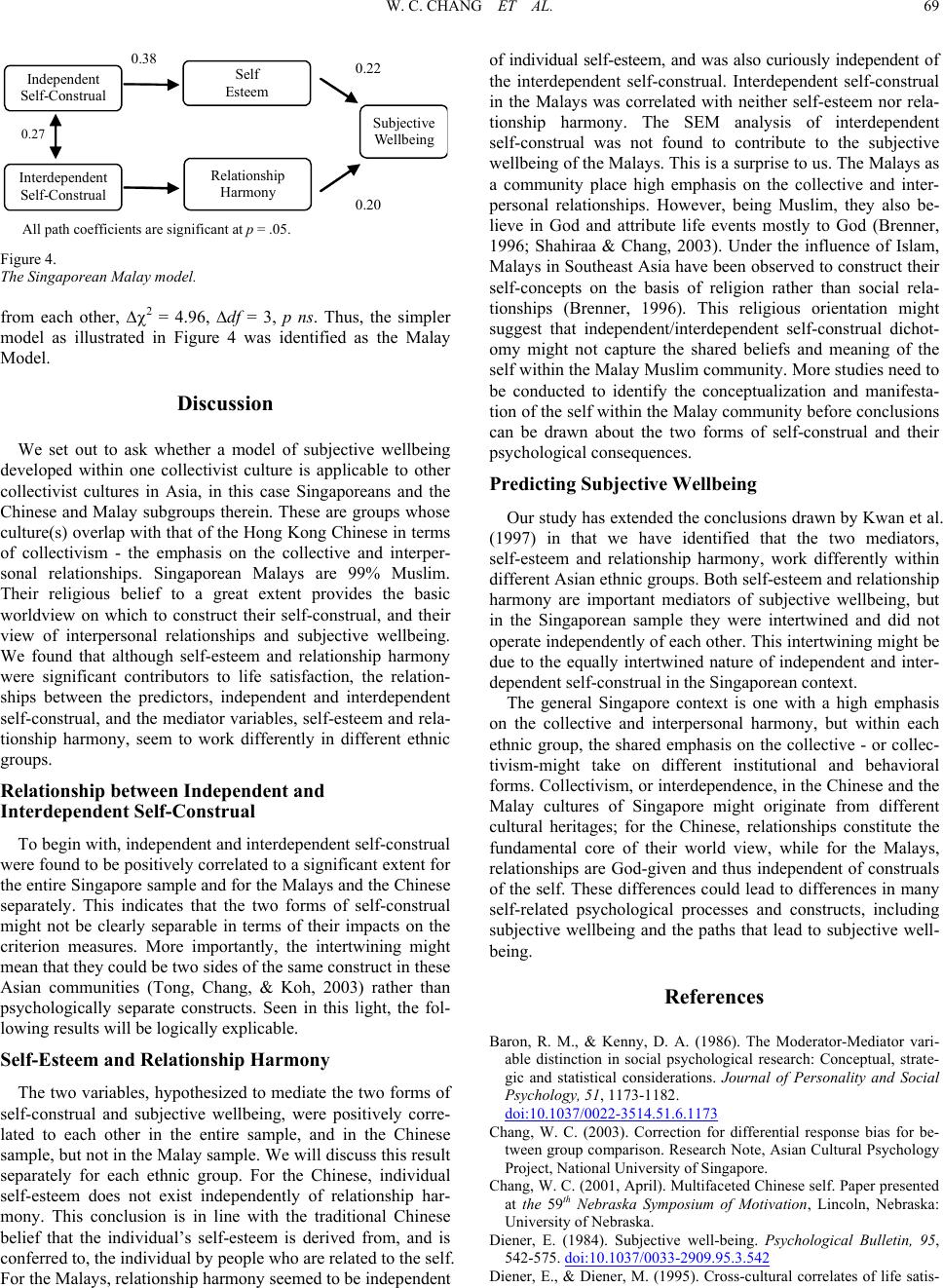

|