S. DE LA CRUZ ET AL.

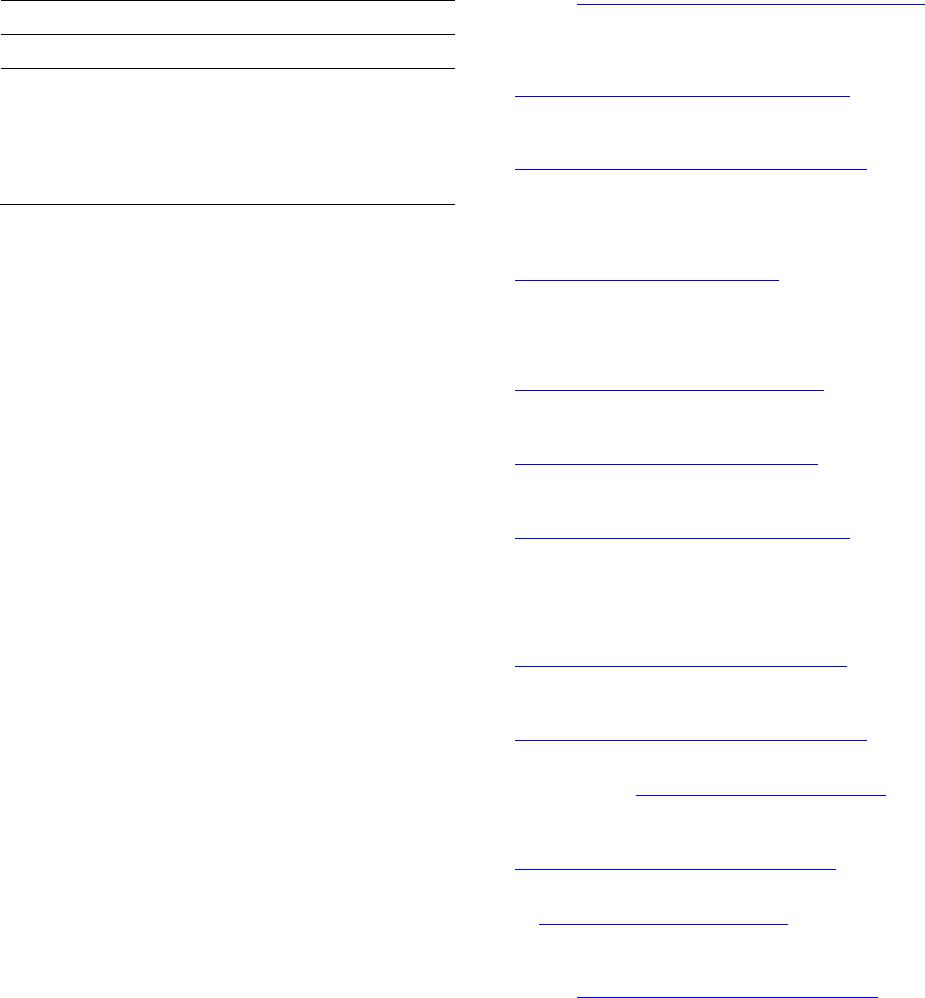

Table 2.

SP evaluation of students’ performance.

% of SPs responding “Yes”

SP Checklist Item Contr ol Intervention p-value

initiated

conversation about nutrition

59% 62% 0.715

64% 63% 0.351

clearly explained the

biological consequ ences of starvation

48% 76% 0.005

The results of this study further supports the idea that films

can be u sed as an adjun ct in medi cal ed ucat io n to provid e expe-

riences that are hard to ensure consistently during clinical

training. The students surveyed as part of this study agreed that

documentary films can be effective tools for teaching and

agreed that “Dying Wish” improved knowledge of the physical

effects of stopping eating and drinking. The efficacy of “Dying

Wish” is consistent with prior studies of humanities modalities

as educational tools for end of life topics (Self, DeWitt, &

Baldwin, 1990; Lorenz, Steckart, & Rosenfeld, 2004; Weber &

Silk, 2007; Kumagai, 2008).

There are some limitations to this study and its assessment.

As the film was shown to students as part of a weeklong mul-

timodal end of life curriculum, it is difficult to isolate the ef-

fects of the film on the changes in self-reported attitudes and

knowledge. It is also unclear how evaluations and self-reported

efficacy at this early point in medical students’ careers will

translate to ability in actual practice. Traditionally self-report

has been an unreliable measure of clinical skill (Davis, Thom-

son, O’Brien, F reemantle, Wol f, Maz manian, & Ta yl o r-Vaisey,

1999).

Conclusion

Although the self-reported knowledge and skills around

counseling patients regarding nutrition and VRFF at the end of

life we re not significantly altered by viewing “Dying Wish”,

the film did affect students’ ability to clearly explain the bio-

logical effects of stopping eating and drinking to SPs. This is

likely due to the film’s visual depiction of the process of stop-

ping eating and drinking at the end of life. Documentaries and

other humanities modalities are considered by students to be

effective teach ing too ls and “Dyi ng Wish” represen ts a feasible

way to deliver instruction regarding VRFF and nutrition at the

end of life. Visual depictions and documentary films that por-

tray the natural courses of illnesses may prove to be helpful,

efficien t teachin g tool s and their role in the educat ional process

for healthcare providers should continue to be studied.

REFERENCES

Alexander, M., Lenahan, P., & Pavlov, A. (2005). Cinemeducation: A

comprehensive guide to using film in medical educat ion. Singapore:

Radcliffe Publishing.

Billings, J. A., & Block, S. (1997). Palliative care in undergraduate

medical education: Status report and future directions. JAMA, 278,

733-738. http://dx.doi.or g/10.1001/jama.1997.03550090057033

Block, S. D., Bernier, G. M., & Crawley, L. M. (1998). Incorporating

palliative care into primary care education. National Consensus

Conference on Medical Education for Care Near the End-of-life.

Journal of General Internal Medicine, 13, 768-773.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.19 98.00230. x

Buss, M. K., Marx, E. S., & Sulmasy, D. P. (1998). The preparedness

of students to discuss end-of-life issues with patients. Academic

Medicine, 73, 418 -422.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/0000 1888-199804000-00015

Davis, D., Thomson O’B rien, M. A., Freeman t le, N., Wolf , F., Mazma-

nian, P., & Taylor-Vaisey, A. (1999). Impact of formal continuing

medical education—Do conferences, workshops, r ounds, and other

traditional cont inuing education acti vities change ph ysician behavior

or health care out co mes? JAMA, 2 82, 867-874.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jam a.282.9.867

Field, M. J., & Cassel, C K. (1997). Approaching death: Improving

care at the en d of lif e. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Fraser, H. C., Kutner, J. S., & Pfeifer, M. P. (2001). Senior medical

stud ent s’ perceptions of the adequacy of edu cation on end-of-li fe is-

sues. Journal of Palliative Medicine , 4, 337-343.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/1096 62101753123959

Gibbins, J., McCoubrie, R., Alexander, N., Kinzel, C., & Forbes, K.

(2009). Diagnosing dying in the acute hospital setting—Are we too

late? Clin ical Medicine, 9, 16-19.

http://dx.doi.org/10.7861/c linmedicine.9 -2 -116

Gibbins, J., McCourbrie, R., & Forbes, K. (2011). Why are newly qual-

ified doctors unprepa red to care for pat ients at the end of life? Medi-

cal Education, 45, 38 9-399.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.20 10.03873. x

Kahn, M. J., Sherer, K., Alper , A. B. , Lazarus, C., Ledoux, E., Ander-

son, D., & Szerlip, H. (2001). Using standardized patients to teach

end-of-life skills to clin ical c lerks. Jour nal of Cancer Education, 16,

163-165.

Kumagai, A. K. (2008). A conceptual framework for the use of illness

na rrati v es in medica l ed ucation. Academ ic Me di ci ne , 83, 6 53-658.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM .0b013e31817 82e17

Lore nz, K. A., Steckart, M. J., & Rosenfeld, K. E. (2004). End-of-life

education using the dramatic arts: The Wit educational initiative.

Academ ic Me di ci ne , 79, 481-486.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/0000 1888-200405000-00020

Nelson, W., Angoff, N., & Binder, E. (2000). Goals and strategies for

teaching death and dying in medical schools. Journal of Palliative

Medicine, 3, 7-16 . http://d x.doi.org/ 10.1089/jpm.2000.3 .7

Schmidt, T. A., Nor ton, R. L., & Tol le, S. W. (1992). Sudden death in

th e ED: Educating residents to compassionately inform families. The

Journal of Emergency Medicine, 10, 643-647.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0736 -4679(92)90155-M

Self, D., DeWitt, C., & Bal dwin , J. (1990). Teaching medical humani-

ties through film discussions. Journal of Medical Humanities, 11, 23-

29. http://d x.doi.org/1 0.1007/BF01142236

Serwint, J. R., & Simpson, D. E. (2002). The use of standardized pa-

ti ents in pedia tric r esiden cy t rainin g in pa lliati ve car e: Anatomy of a

stan dar dized pat ient ca se sc ena rio. Journal of Palli ative Med icine, 5,

146-153. http://d x.doi.org/10.1089 /10966210252785123

Van d er Ri et , P., Good, P., Higgins , I., & Sneesb y, L. (2008). Palliative

care professionals’ perceptions of nutrition and hydration at the end

of life. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 14, 145-151.

Weber, C. M., & Silk, H. (2007). Movies and medicine: An elective

using film to reflect on the patient, family, and illness. Fam ily Me di-

cine, 39, 317 -319.

OPEN ACCE SS

96