Psychology 2014. Vol.5, No.1, 15-19 Published Online Janu ary 201 4 in Sci R es (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.51004 Comparing the Recall to Pleasant and Unpleasant Face Pictures in Depressed and Manic Individuals Mehran Sardaripour Department of Clinical Psychology, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Karaj, Iran Email: msardaripour@yahoo.com Received October 24th, 2013; revised November 26th, 2013; accepted December 23rd, 2013 Copyright © 2014 Mehran Sardaripour. This is an open access article distributed under the C reative Commons Attribution License, which pe rmits unrestricted use, distribu tion, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Mehran Sardaripour. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. The main purpose of the present study is to compare the perception of recalling pleasant and unpleasant face pictures in the case of depressed and manic people. Methodology: The present study is an analysis based on a comparative type research; the statistical sample is made up of depressed and manic people (males) referred to LAVASANI Hospital in Tehran City using Beck’s depression questionnaire and a di- agnostic interview based on (SCID) DSMIV 30 depressed individuals who were selected after the process of screening. Ranging from moderate to high depression levels (with a cut-off point of 21 and higher), samples of 30 people with manic and 30 depressed people were compared with 30 healthy individuals. It should be mentioned that three groups were convergent in terms of age, gender, marital status and educa- tional level. Then, a test involving computer-based cognitive-neural recall (emotional facial Pictures) was carried out on the related subjects. Findings: A t test of both independent groups was used to evaluate the convergence of the groups and multi variable bilateral variance analysis (MANOVA) was used to assess the pleasant and unpleasant perception of images among three groups. The results of the study showed that there is a difference among three groups in terms of recalling pleasant and unpleasant faces so that the depressed group shows a higher level of recall in terms of unpleasant images than the other two groups, but it indicates little recall of pleasant images in comparison to the other two groups (p < 0/05). Conclusion: The findings of the present study include some explicit outcomes in relation to the applica- tion of therapeutic approaches and concentrated educational methods on the amendment of emotional bias in depressed and manic people. Keywords: Depression; Manic; Pleasant Face Image; Unpleasant Face Pictures Introduction The process of recognition has an important role in playing with regard to emotions. Based on the theory of recognition, emotions determine the cognitive evaluations as to whether or not emotions are experienced. And, if so, which kinds of emo- tions are experienced. Consequently, basic recognition is a way in which we can handle and control these emotional and moral situations. Biases and deficits in terms of cognitive perform- ance and the ability to regulate emotion and mood states can potentially be affected by increasing these disorders in emo- tions (Joormann, Yoon, & Siemer, 2009). Based on the cogni- tive theories regarding depression, negative bias in processing the related information (for example Beck, 1976) is one of the most crucial traits of depressed people, particularly in terms of negative attention bias (Murrough, Lacoviello, Neumeister, Chaney, & Losifescu, 2011). Generally, these kinds of models suggest that these biases in memory, perception and attention lead to the survival of the depression. (Kellough, Beevers, Ellis, & Wells, 2008). In fact, clinical depression may be accompa- nied by a large number of cognitive disorders such as percep- tion bias, attention and memory. There may be a negative emo- tional context and a reduction in terms of the speed and accu- racy of emotion and cognitive processes, particularly in terms of executive functions (Chepenik, Cornew & Farah, 2007). Many stimulants can affect people simultaneously. What people practically perceive depends not only on the stimulants, but also depends on the whole processes of cognition reflecting the tendencies, purposes and personal expectations in a moment. In other words, cognitive processes (perception, attention, analysis) have a determining role in this relationship (Atkinson et al., 1983, translated by Berahani et al., 2008). It is expected that depressed people are selective attention to negative stimulants. These kinds of biases play a key role in preserving and con- tinuing the longevity of the depression (Kellough et al., 2008). On the one hand, manic people also show disorders in terms of memory and planning tests, but they are different in terms of emotional function in comparison to depressed people. “Manic patients were impaired in their ability to inhibit behavioral re- sponses and focus attention, but depressed patients were im- paired in their ability to shift the focus of attention” (Murphy et al., 1999). Also, an intensified sensitivity is observed in the behavioral activity system in these people (Johnson, Edge, Holms, & Carver, 2012). While depressed people usually show a shift in the focus of attention disorder (Murphy et al., 1999), OPEN ACCESS 15 M. SARDARIPOUR they also show intensified sensitivity in their behavioral inhibi- tory system (Hundt, Nelson-Gray, Kimbr el, Mit chel l, & Kwapil, 2007; Pinto-Meza et al., 2006, quoted of Vergara-Lopez, Lo- pez-Vergara & Colder, 2012). Generally, depressed people have a bias to negative stimulants, while manic people have a bias to positive emotional biases (Murphy et al., 1999). In terms of neurological function, Amygdale is an essential connective lobe in terms of recognition and the manner in which the brain plays a key role in memory, perception and manner (Chepenik, Cornew, & Farah , 2007). Indeed, the attention bias of depressed patients is represented by increasing the neurotic response to the negative emotional demonstrations in the Amygdale lobe. However, few studies have been carried out in relation to the reduction of Amygdale activity with regard to positive stimu- lants. In this sense, Suslow et al. (2010) found that the Amyg- dale extra-activation to the negative stimulants in depressed people is related to the negative bias of emotion steps (Cusi, Nazarov & Holshausen, 2012). Stuhrmann, Suslow, & Dann- loeski (2011 quoted of Ajilchi & Nejati, 2013) in a review of 20 pieces of research about face processing among depressed peo- ple, reported abnormalities and disorders in the face of proc- essing net, indicating that the processing bias related to mood disorder that connects to the Amygdale, Insula, parahippocam- pal Gyrus, fusiform, putamen, cingulare and rbitofrontal cortex, so that the reduction in pre-frontal lobe activity in depression may be affected by the negative bias in attention and memory (Beevers et al., 2010; Fales et al., 2008; Koster et al., 2010, quoted in Capecelatro, 2013). In addition, depressed people show problem with regard to perceptions of social symptoms such as negative bias to emotional faces in comparison to health individuals (Gur, Erwin, Gur, Zwil, Heimberg, & Kraemer, 1992; Bouhuys, Geerts, & Gordijn, 1999). These biases in- crease with responses, and the neural net lobes are challenged in processing the emotions, therebye increasing the response of the Amygdale to the representation of negative appearances in depressed people in comparison to healthy ones (Suslow et al., 2010; Viktor et al., 2010, quoted in Ajilchi and Nejati, 2013). In a study led by Capecelatro et al. (2013), it was shown that people with more than five years of depression have a higher application of negative words, and little emotional positive statements in this regard. The results of the study indicate that the period of depression has a direct relationship with negative stimulants in terms of the recall process. The results of the experimental research indi- cates that manic symptoms are increasing, so that the risk of developing the mania along with positive sustainable emotions even in a negative context, can also happen in this case (Gruber, 2011; Gruber, Johnson, Oveis, & Keltner, 2008; Gruber, Har- vey, & Purcell 2011, quoted in Dutra et al. forthcoming). The clinical mania background of people has been reduced in com- parison to those of healthy ones, due to the social recognition tasks and their neural activity in the related lobes with the rep- resentation of others emotions (Kim et al., 2009 quoted in Dutra et al. forthcoming). Manic people have seen the reduction in activity in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) and hyper activity in Amygdale in terms of their emotional tasks. In fact, the reduction in frontal inhibitory activation among these patients may increase the Amygdale activity in such a case. While it is modulated in healthy people of course, when the subjects are motivated due to their determination and the labeling of these emotional actions (Foland et al., 2008, 2012), it seems that the extra-activation acts in conjunction with the mood-related affairs of these people. However, the reduction activity in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex is related abnor- mality with trait-related of their illness (Foland et al., 2012). The logic of applying pleasant and unpleasant faces in the ap- pearance of the subjects, the readiness of humans biologically, the phenomenological emotion of face demonstration, even unconsciously (Dimberg, Thunberg, & Elmehed, 2000; Falla & Hamilton, 1998), and the closeness of the face to the real situa- tions compared with words (Moog & Bradley, 2002) was con- sidered in this regard. Recent theories about recognition and emotion suggest that emotional states can cause bias in the orientation of processing cohesive information with emotional moods (Reidy & Richard, 1997). Since these biases play a key role in the continuation of emotional disorders (depression and mania), the carrying out of the present study not only helps to determine cognitive abnormalities, but also assists in finding and amending the application of some approaches in this case. Also, the accurate evaluation of these negative biases can rep- resent new approaches in terms of emotional disorders, lead- ing to the appearance of new therapeutic methods along these lines. Based on this, and due to the lack of recent studies in this field, the present study aims at potentially dealing with the related issu es. Hence, the research hypothesis is as follows: 1) The recall of emotional faces in depressed people is dif- ferent from that in the case of healthy individuals. 2) The recall of emotional faces in manic people is different from that in the case of healthy individuals. 3) The recall of emotional faces in manic people is different from depressed individuals. Method Procedure The present study is a comparative analytical type of re- search. Independent variable is mood (group) and dependent variable is perception of pleasant and unpleasant images. The present study is a comparative analytical type of research. The sample used in this study involves males ranging from 20 to 25 year of age who exhibit symptoms of depression and mania who were referred to LAVASANI Hospital in Tehran City in 2011. The clinical diagnosis was based on unstructured inter- views matched with the textual criteria and edited in terms of the fourth diagnostic guidelines and psychiatric disorders statis- tics (SCID) DSMIV available to psychologists in this regard. 30 depressed patients and another 30 manic patients acted as the available sample of the research. In addition, another 30 people with no background of psychological abnormalities were matched in terms of age, gender, marital status and educa- tional level and were then compared in the research. In the group with depression and mania, the entry conditions to the study were subject to the diagnostic criteria of the disorders matched to (SCID) DSMIV criteria, and also included those gaining a score of 21 and higher in the Beck’s questionnaire. They also exhibited a lack of bipolar antecedents. In the healthy group, the lack of a psychiatric background was considered as an entry conditions to the study. Data were analyzed by one- way analysis of variance used SPSS, version 20. Instrument Demographic Features Questionnaire This questionnaire was prepared by the researcher to deter- OPEN ACCESS 16  M. SARDARIPOUR mine the demographic features of the subjects such as age, gender, marital status and educational level. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) This test was designed by Beck et al., the depressive symp- toms being measured by this test include emotional symptoms, and motivational, cognitive, physical and plantar affairs in this relationship. Beck has reported the reliability of the test at 0.93 using the Spearman-Brown method. This questionnaire con- tains 21 questions, every one of which has four choices (0, 1, 2, and 3). The subjects draw a circle around the number showing their feelings as a suitable response. Fata (1991) reported the correlation coefficient between the Beck Depression Inventory and the Hamilton Depression Scale among Iranian subjects - 0.66 in this case (Ajilchi & Nejati, 2013). Structured Clinical Interview for (SCID) DSM-IV SCID is a semi structured interview for making the major DSM-IV Axis diagnoses, this is an interview-based test de- signed to be easy to facilitate and apply by clinical psycholo- gists (Spiterz, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1992). Many different studies have shown the suitability of the questionnaire in terms of reliability and validity (Williams, Gibbon et al., 1992; Martin, Pollack, Bukstein, & Lynch, 2000; Skre, Onstad, Torgersen, & Kringlen, 1991; Zanarini & Fran- kenburg, 2001, quoted in Sharifi et al., 2004). In Iran Sharifi et al. (2004) the authors also indicated that this interview has a suitable reliability and validity and reported the Kappa Coeffi- cient to be 0.52 in this case. Computer-Based Software to Represent the Pleasant and Unpleasant Stimulants In this test, 18 pairs of face images demonstrating sad and happy emotions were extracted using the Nim Stim data bank. (Tottenham et al., 2009) and were used as a stimulant in this case. As shown in Figure 1, the images and dots were repre- sented in two frames of the rectangle with 2 cm from the dis- play central fixed point. The subject stood 50 cm from the computer. First, an empty frame and fixation point (+) were presented for 500 thousands of a second; then, two faces to the left and right of the fixation point of the display were also pre- sented for 500 thousands of a second. The subjects were asked to recall the number of happy and sad faces in this case. The test was undertaken by the use of a laptop. Finding The research variables are shown in Table 1 in terms of their type of separation. As is shown in Table 1, we can see that the mean recall process is different between the three groups. In order to evaluate the significance of these differences, a single-sided variance analysis was applied. The insignificance of the Levin test showed the establishment of variances’ as- similations among three groups; hence, the results of the vari- ance analysis are represented in this case. According to the results shown in Table 2, it can be stated that there is a significant difference between the three groups of depressed, manic and control cases at the p < 0.05 level. The results of a Tooki follow-up test are given in Table 3 in order to determine and specify the establishment of these dif- ferences. Figure 1. Comoputer based software to represent the pleasant and unpleasent images. Table 1. Descriptive findings related to happy and sad pleasunt and unpleasant images by groups s eparation. Type of representation Group Mean Std deviation Pleasant Depressed 3.53 0.973 Manic 4.90 1.44 Control 4.73 1.55 Unpleasant Depressed 5.63 1.79 Manic 3.97 1.67 Control 4.50 1.57 Table 2. One way analysis of variance for pleasunt and unpleasant images. representation Source squares Df squares F Sig Pleasant Between group 33.35 2 16.67 9.18 0.001 Within group 158.03 187 1.81 Unpleasant Between group 43.46 2 2.82 7.70 0.001 within group 245.43 187 Table 3. Tukey test for defferences between groups in pleasant and unpleasant images. Type of representation Group 1 Group 2 Mean of differen ces Std estimation error Pleasant D epressed Manic −1.36 0.348 Control −1.20* 0.348 Manic Control 0.167 0.348 Unpleasant Depress ed Manic 1.66 21.73 Control 1.133 2.82 Manic Control 0.533 2.75 According to Table 3, we find out that there is a significant difference between both groups of depressed and manic and depressed and control cases in the dimension of pleasant face recall cases at the p < 0.05 level. However, there is no observed significant difference between manic and control groups. Also, there is a significant difference between depressed with manic OPEN ACCESS 17  M. SARDARIPOUR and depressed with control groups in terms of the dimension of the unpleasant face recall process, but there is no found differ- ence between the manic and the control group. Discussion The findings of the present study show that in the depressed group, the degree of recall of pleasant emotional faces is low in comparison to the manic and control groups, and the degree of recalling unpleasant images is high among the related groups. This result is coincident with the results obtained by Storman et al. (2011), Suslow et al. (2010), Modinos et al. (2013), Murphy et al. (1999) and Viktor et al. (2010) based on depressed peo- ple’s tendency to favor unpleasant stimulants, and their avoid- ance of pleasant stimulants. Generally, it is specified that de- pressed people have emotional biases with regard to negative stimulants. In fact, they act in relation to their own mood state, particularly in the case of emotional stimulants. Depressed people pay a great deal of attention to negative stimulants due to the low level of their mood. In contrast, manic people show positive reactions due to their high mood state and, as a result, they process their affairs more, trying to retain them in their memory. As was motioned before, the tendencies of both groups relate to neural processes and brain lobes in terms of emotional processes. In fact, in both groups, the reduction of related prefrontal cortex activity and the increase of Amygdale activity is seen in this case. These changes lead to an activity among depressed people when they are faced with negative stimulants and in manic people when they are faced with posi- tive stimulants. On the other hand, it is obvious that the first step is subject to the process of bias because attention is the foundation and basis of the whole cognitive approach, consid- ering the inventory and entry of the information into the brain (Arjmandi et al., 2012). It is, of course, defined as a clear con- centration of the objects and the mind, or a chain of simultane- ous stimulants (Cohen, 1990, quoted in Arjmandi et al., 2012). Thus, it seems that the correction of emotional biases regarding the mood state in the attention step can prevent the next biases in terms of information processing, perception and saving in the memory, and then the recall process. On the other hand, this tendency regarding emotional mood stimulants can be repre- sented by the motivational system of people. The motivation appears in different forms due to people’s differences in terms of emotional and sensitivity reactions (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Researchers have shown that depression accompanies a default in the motivation system leading to weaknesses in the reaction to positive and intense events (Zinbarg & Yoon, 2008). Fowles (1994) believes in this relationship that depression is generated by interaction in terms of two motivation systems – the behav- ioral approach system (BAS) and the behavioral inhibition sys- tem (BIS). The first system is subject to the sensitivity of moti- vating the one towards them, while the second one is related to the disgusting conditions and new stimulants motivating avoidance in this regard (Gray, 1982). Based on this viewpoint, the depression feature may be subject to a lack of interest in experiencing pleasant cases (due to the failure of behavioral inhibition system activity) and sensitivity to the bothering events (due to the increase in inhibitory system activity). In contrast, manic people have problems in terms of their behav- ioral responses’ inhibition ability; that is, it seems that despite the existence of depressed people. In terms of a manic person, the behavioral approach system is reduced. Indeed, depressed people pay attention to negative stimulants while manic ones pay attention to the positive stimulants in their events. Conclusion The most important point is that in the present study, there is an observed difference between depressed people and the manic and control groups in terms of tending towards the recall of unpleasant stimulants, while pleasant stimulants are preferred by manic people. However, a difference was found between manic groups and healthy ones in tending to be able to recall unpleasant stimulants. Based on the findings of the present study, manic people show a high tendency towards positive stimulants in comparison to people in the healthy group. It may be closely related to signs of manic tendencies in these people. Maybe the intensity of manic signs could not be evaluated. Based on this, it is suggested that future studies should be based on manic patients in terms of their intensity categorization. The limitation of the statistical sample consisting of only male pa- tients and one hospital in Tehran, as well as the limitations of the size of the sample has been considered as limitations of the present study. It is also recommended that researchers consider gender comparisons in future research. REFERENCES Ajilchi, B., & Nejati, V. (2013). Attention Bias to Sad Faces and Im- ages: Which Is Better for Predicting Depression? Open Journal of Depression, 2, 19-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojd.2013.23005 Atkinson, R., et al. (1983). Hilligard psychology. Translated by M. N. Berahani et al. (2008). Tehran: Roshd Publication. Arjmandi Beglar, A., Nejati, V., & Najafi Kupayee, M. (2012). The effects of coronary artery bypass graf t on selective attention, sh ifting attention, and sustained attention. Annals of Biological Research, 3, 2028-2033 Bradley, B. P., Mogg, K., & Lee, S. C. (1997). Attention biases for negative information in induced and naturally occurring dysphoria. Behavior Res earch and therapy, 35, 911-927. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00053-3 Bouhuys, A. L., Geerts, E., & Gordijn, M. C. (1999). Depressed pa- tients perceptions of f acial emotions in depressed and remitted stat es are associated with relapse: A longitudinal study. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorder, 187, 595-602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199910000-00002 Capecelatro, R. M., Sacchet, D. M., Hitchcock, F. P., Miller, M. S., & Britton, B. W. (2013). Major depression duration reduces appetitive word use: An elaborated verbal recall of emotional photographs. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47, 809-815. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.01.022 Chepenik, G. L., Corne w, A. L, & Farah, J . M. (2007). the Influence of Sad Mood on Cognition. Journal of Emoti on, 17, 802-811. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.802 Cusi, A. M., Nazarov, A., & Holshausen, K. (2012 ). Systematic review of the neural basis of social cognition in patients with mood disorders. Journal of Psychiatry Neurosciense, 37, 154-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/jpn.100179 Dimberg, U., Thu nberg , M., & Elmehed, K. (2000). Uncon scious facial reaction to emotional facial expressions. Psychological science, 11, 86-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00221 Durta, J. S., West, V. T., Impett, A. E., Oveis, C., Kogan, A., Kelther, D., & Gruber, J . (2013). Rose-Colo red Glasses Gone too far? Mania symptoms predict Biased Emotion Experience and Perception in Couples. Journal of Motivation and Emotion, in press. Foland, C. L., Altshuler, L. L., Bookheimer, Y. S., Eisenberger, N., Townsend, J., & Thompson, M. P. (2008). Evidence for deficient OPEN ACCESS 18  M. SARDARIPOUR modulation of amygdale response by prefrontal cortex in bipolar ma- nia. Journal of Neuroimaging, 162, 27-37. Foland-Ross, C. C., Bookheimer, Y. S., Lieberman, D. M., Sugar, A. C,. Townsend, J. D., Fischer, J., Torrisi, S., & Altshuler, L. L. (2012). Normal amygdale activation bu t deficient ventrolateral prefrontal ac- tivation in adults with bipo lar disorder euthymia. Journal of Neuroi- mage, 59, 738-744. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.054 Fowles, D. C. (1994). A motivational theory of psychopathology. In W. Spaulding (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation. Integrated views of motivation and emotion (Vol. 41, pp. 181-228). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Gray, J. A. (198 2). Th e neuropsychology of anxiety: An inquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Oxford: Oxford Univer- sity Press. Gur, R. C., Erwin, R. J., Gur, R. E., Zwil, A. S., Hei mberg, C., & Kra- emer, H. C. (1992). Facial emotion discrimination, II, behavioural findings in depression. Psychiatry Research, 42, 241-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(92)90116-K Johnson, S. L., Edge, M. D., Holmes, M. K., &, Carver, C. S. (2012). The Behavioral Activation System and Mania. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 243-267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143148 Joormann, J., Yoon, K. L., & Siemer, M. (2009). Cognition, attention, and emotion regulation. Journal of Emotion Regulation and Psycho- pathology, 174-203 Kellough, J. L., Beevers, C. G., Ellis, A. J., & Wells, T. T. (2008). Time course of selective attention in clinically depressed young adults: An eye tracking study. Behavior Journal of Resear ch Th era py, 46, 1238-1243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.07.004 Modinos, G., Mechelli, A., Pettersson-Yeo, W., Allen, P., Philip McGuire, P., & Ale man, A. (20 13). Pattern classificatio n o f brain ac- tivation during emotional processing in subclinical depression: Psy- chosis proneness as potential confounding factor. Peer Journal, 1, e42. http://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.42 Mogg, K. & Bradlley, B. P. (2002). Selsctive orienting of attention to makes threat faces in social anxiety. Behavioral Research Therapy, 40, 1403-14014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00017-7 Murphy, F. C., Sa hakian, B. J., Ru binsztein, J. S., Mich ael, A., Rogers, T. W., & Paykel, E. S. (1999). Emotion bias and inhibitory control processes in mania and depression. Psychological Medicine, 29, 1307-1321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799001233 Murrough, J. W., Lacoviello, B., Neumeister, A., Chaney, D. S., & Losifescu, D. V. (2011). Cognitive dysfunction in depression: Neu- rocircuitry and new therapeutic strategies. Journal of Neurobiology of Learning and Me mory, 96, 553-563. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2011.06.006 Reidy, J., & Richards, A. (1997). Anxiety and memory: A recall Bias for threatening word in high anxiety. Journal of Behavior Researches and Therapy, 35, 537542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00001-6 Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In S. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology, Social, emotional, and person- ality development (Vol. 3, p . 99). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Sharifi, V., Asaadi, S . M., Mohammadi, M. R., Amini , H., Kaviani, H., Semnani, Y., Shaabani O., & Jalali Roudsari, M. (2004). Validity and ability of achieving the Persian version of structured diagnostic interview SCID (DSMIV). Cognitive Sciences, 6, 76-89. Spitzer, R. L. Williams, J. B., Gibbon, M., & First, M. B. (1992). The Structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, Ra- tionale, and Description, Archives of General Psychology, 49, 624- 629. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005 Tottenham, N., Tanaka, J., Leon, A. C., McCarry, T., Nurse, M., & Hare, T. A. (2009). The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judg- ments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Research, 168, 242-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006 Vergara-Lopez, C., Lopez-Vergara, H. I., & Colder, C. R. (2012). Ex- ecutive functioning moderates the relationship between motivation and adolescent depressive sy mptoms. Journal of Personality and In- dividual Differences, in press. Zinbarg, R. E., & Yoon, L. K. (2008). RST and clinical disorders: Anxiety and d epression. In P. J. Corr (Ed.), The reinforcement sensi- tivity theory of personality (pp. 360-397). New York: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819384.013 OPEN ACCESS 19

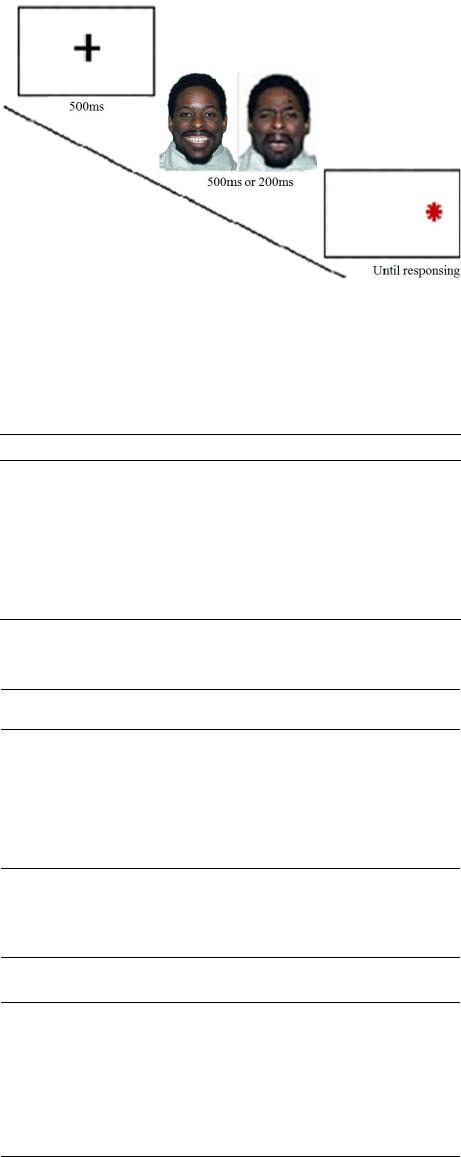

|