Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.12A, 21-29 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.412A1004 Open Access 21 Critical Thinking in Health Sciences Education: Considering “Three Waves” Renate Kahlke1, Jonathan White2 1Department of Educational Policy Studies, Faculty of Education, Un i ve rsity of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada 2Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmont on, Canada Email: rkahlke@ualberta.ca Received September 6th, 2013; revised October 6th, 2013; accepted October 13th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Renate Kahlke, Jonathan White. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Renate Kahlke, Jonathan White. All Copyright © 2013 are gu arded by law and by SCI RP as a gua r di an . Historically, health science education has focused on content knowledge. However, there has been in- creasing recognition that education must focus more on the thinking processes required of future health professionals. In an effort to teach these processes, educators of health science students have looked to the concept of critical thinking. But what does it mean to “think critically”? Despite some attempts to clarify and define critical thinking in health science education and in other fields, it remains a “complex and con- troversial notion that is difficult to define and, consequently, difficult to study” (Abrami et al., 2008, p. 1103). This selected review offers a roadmap of the various understandings of critical thinking currently in circulation. We will survey three prevalent traditions from which critical thinking theory emerges and the major features of the discourses associated with them: critical thinking as a set of technical skills, as a humanistic mode of accessing creativity and exploring self, and as a mode of ideology critique with a goal of emancipation. The goal of this literature review is to explore the various ways in which critical think- ing is understood in the literature, how and from where those understandings emerge, and the debates that shape each understanding. Keywords: Critical Thinking; Medical Education; Nursing Education; Higher Education; Adult Education; Social Work Education; Higher-Order Learning Introduction: What Is Critical Thinking? Over the years, many attempts have been made to create a general definition of critical thinking (e.g. Black, 2008; Facione, 1990). Given analytic philosophy’s emphasis on reasoning and logic, many departments of philosophy have claimed expertise over critical thinking (Brookfield, 2012). However, there are many different ways of understanding critical thinking, ema- nating from a wide variety of epistemological and theoretical positions (Brookfield, 2012). Many authors have lamented that critical thinking means many different things to different peo- ple, and that there is a lack of consensus (e.g. Black, 2008; Fischer, Spiker, & Riedel, 2009). However, we believe that the fragmentation of discourses on critical thinking may be repre- sentative of fundamental differences in epistemological and normative beliefs—that is, what critical thinking means varies depending on what people believe about how and why we en- gage in thought. Further, individuals’ understandings of critical thinking may vary depending on the disciplinary and practice contexts in which the thinking takes place. The term critical thinking can hold many different meanings, both within and between traditions. Thus, instead of attempting to define critical thinking, em- bracing some traditions while excluding others, this literature review will treat critical thinking as an array of “kinds of think- ing and styles of reasoning” (Mason, 2009, p. 13), each ema- nating from different theoretical and normative positions, and different disciplinary and practice contexts. Each critical think- ing tradition, with its attendant assumptions, will have strengths and weaknesses for educational theory; thus, like Yanchar, Slife, & Warne (2008), we hold that “no approach is likely to be uni- versally accepted or to provide sufficient resources for critical analysis across all fields and under all circumstances” (p. 269). Rather, it is important to understand the roots and assumptions behind these various perspectives in order to understand and critically evaluate them in context. In introducing her edited book on critical thinking, Re-thinking Reason, Walters (1994a) proposes an historical progression of critical thinking scholar- ship beginning with a “first wave”—where critical thinking is understood as a set of logical procedures “that are analytical, abstract, universal, and objective” (p. 1). The “first wave” fo- cuses on improving reasoning processes. Because this approach largely looks at critical thinking as a set of skills, techniques or procedures, it has also been referred to as the technical or in- strumental approach (Jones-Devitt & Smith, 2007); we will refer to it as the “technical” approach here. The “second wave” of critical thinking scholarship is led by scholars who believe that purely technical approaches amount to a reduction of critical thinking to a set of procedures. Second wave scholars seek to emphasize the creative, “affective, theo-  R. KAHLKE, J. WHITE retical, and normative presuppositions” (Walters, 1994a, p. 2) that they believe to be inherent in critical thinking. The second wave offers a constructivist critique of the idea that knowledge can be objectively accessed; it seeks to embrace the “liberal humanist assertion that critical thinking be understood contex- tually” (McLaren, 1994, p. xii). Critical thinking in the second wave becomes a highly contextual and creative process. Be- cause of this interest in reasserting the role of human unique- ness, self-exploration, and social interaction, like McLaren (1994), we have called Walters’s (1994a) second wave the “humanist” tradition in critic al thinking. In his forward to Walters’s book, McLaren (1994) suggests the addition of a “third wave” of critical thinking theory, which “speak[s] to critical pedagogy’s concern with reasoning as a sociopolitical practice” (p. xii), drawing on the deconstruc- tionism in critical theory and critical pedagogy. Like Walters’s (1994a) second wave, McLaren’s (1994) third wave under- stands knowledge as inherently constructed, and takes social deconstruction as its guiding philosophy. The normative di- mension of the “third wave” is emphasized, understanding thinking as always-already a political project. Since the third wave is linked to issues of social justice and emancipation, I have called it the “emancipatory” approach to critical thinking. Figure 1 maps these three traditions in critical thinking theory and indicates their relationship to other concepts that will be discussed later in this paper. Because of its applicability across disciplinary contexts, Wal- ters and McLaren’s framework will be used in this review as a way of positioning various approaches to critical thinking ac- cording to their epistemological and normative assumptions; however, not all approaches will fit squarely within one “wave” or another. Many approaches draw on elements of more than one “wave,” and understandings may shift depending on the practice context. Moreover, these “waves” might be better thought of as traditions, since they do not occur as a linear his- torical progression. For example, Walters’ first wave—where critical thinking is a set of technical skills, understood through analytic philosophy’s concern with reasoning processes—is still very much the dominant understanding today (Brookfield, 2012). Similarly, McLaren’s (1994) third wave does not neces- sarily follow on the heels of the second wave, particularly given that it emanates from much earlier ideas about critical thinking linked to critical pedagogy, such as Paulo Freire’s concept of critical consciousness first developed in Pedagogy of the Op- pressed (Freire, 1996) and first published in Portuguese in 1968. The remainder of this review will look at each “wave” in Wal- ters and McLaren’s framework, attending to how these dis- courses have been taken up in the health sciences. Technical Critical Thinking The technical approach to critical thinking is still the domi- nant approach today (Brookfield, 2012; Jones-Devitt & Smith, 2007; Yanchar, Jackson, Hansen & Hansen, 2012). This ap- proach is derived from the discipline of analytic philosophy (Brookfiel d, 2012) and—though some defi nitions of critical think- ing within this category also recognize that there may be dispo- sitions or attitudes that contribute to critical thinking (e.g. Faci- one, 2011; Fischer, Spiker, & Reidel, 2009; Halpern, 2009)—pri- marily looks at critical thinking as a set of techniques or general Figure 1. Three traditions in critical thinking. Open Access 22  R. KAHLKE, J. WHITE skills that can be taught. Technical understandings of critical thinking are connected to specific techniques such as “recognizing logical fallacies, distinguishing between bias and fact, opinion and evidence, judgement and valid inference, and becoming skilled at using different forms of reasoning (inductive, deductive, formal, in- formal, analogical, and so on)” (Brookfield, 2012, pp. 32-33). It is heavily linked to—sometimes overlapping or encompass- ing—other constructs, such as reasoning (Black, 2008; Bowell & Kemp, 2001; Facione, 2011; Lipman, 1988; Mason, 2009; Missimer, 1994; Nosich, 2005; Thomson, 2001), problem- solving (Mason, 2009; Nosich, 2005), evidence appraisal (Brookfield, 2012; Halpern, 2003; Thomson, 2001), and reflec- tion (Abu-Dabat, 2011; Black, 2008; Garrison, 1992; Halpern, 2003; Nosich, 2005). This approach is present in the majority of critical thinking “self-help” resources, offering solutions for teaching and learning critical thinking skills (e.g., Bowell & Kemp, 2001; Epstein, 2003; Halpern, 2003; Nosich, 2005, Thomson, 2001). The Delphi Consensus: A Definition The technical understanding of critical thinking is far from conceptually coherent. Definitions of critical thinking within this tradition abound (e.g., Black, 2008; Ennis, 1962; Facione, 1990, Lipman, 1988); recent reviews of the literature have “re- vealed many different conceptions of CT [critical thinking] with only a modest degree of overlap” (Fischer et al., 2009, p. 5). In 1990, Peter Facione (1990) published the American Phi- losophical Association’s Delphi Report, to which many major critical thinking theorists contributed (including Robert Ennis, Mathew Lipman, Stephen Norris, Richard Paul and Mark Weinstein). Although the Delphi Report has not served to pro- vide a single definition for critical thinking (Fischer et al., 2009), it is likely the most widely recognized and contributed to definition of critical thinking in circulation; moreover, it covers many concepts that consistently reappear in debates about critical thinking in the technical tradition. The report defines critical thinking broadly, as purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in in- terpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. CT [critical thinking] is essential as a tool of inquiry. (Facione, 1990, p. 2) This definition focuses on critical thinking as reasoning, evaluation and judgment. The Delphi Report also indicates a set of six critical thinking skills required to make such judgments, including interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, expla- nation and self-regulation. The majority of these skills are un- derstood as part of “the” reasoning process—in order to think through a problem or issue, the thinker goes through a process of gathering, interpreting, analyzing and evaluating information, making inferences and generating an explanation or decision based on that information. Like other conceptualizations of critical thinking, the report also lists a series of affective dispo- sitions, which are said to support critical thinking, these include: inquisitiveness, concern to become well-informed, alertness, trust in the inquiry process, self-confidence in one’s reasoning skill, open-mindedness, flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions, understanding of others’ opinions, fair-minded- ness, honesty in evaluating one’s own biases and prejudices, prudence in judgement, willingness to reconsider or re-evaluate judgments, clarity, orderliness, diligence, reasonableness, care, persistence, and precision (Facione, 1990). These skills and attitudes provide a starting point for a definition of critical thinking in the technical tradition, though these are contested even within this tradition. The sections below look at the many ways in which the meaning of critical thinking is contested both within and between traditions. Major Debat es Several major debates exist within the technical critical thinking tradition. First, scholars in the technical tradition ques- tion the extent to which critical thinking requires the affective dispositions or attitudes discussed above—as opposed to in- cluding only reasoning skills. Although the Delphi report de- fined critical thinking as encompassing both skills and disposi- tions, the contributors were quite divided on this issue—only a two-thirds majority agreed that dispositions could be included in a definition of critical thinking (Facione, 1990). Perhaps the reason that this issue is so contentious is that a focus on affec- tive dispositions to some extent takes critical thinking away from the domain of purely technical reasoning procedures, a hallmark of critical thinking in this tradition. Instead, critical thinking is at least in part a quality of the thinker, rather than strictly a behaviour. While technical critical thinking skills might be teachable, the educational processes involved in changing attitudes or dispositions—if, in fact, dispositions can be changed—continues to be murky ground (Tishman, Jay, & Perkins, 1993). Second, debates continue to rage around the extent to which critical thinking skills are domain specific, as opposed to a set of general and transferable skills and abilities. Many early criti- cal thinking scholars argued that critical thinking is comprised of a general set of skills that, once learned, can be applied to any subject. Ennis (1989, 1990) is credited with championing this approach. McPeck (1990, 1994), on the other hand, argues that critical thinking skills are particular to a subject and disci- pline; a certain amount of disciplinary fluency is required in order to engage in critical thinking in any subject, and critical thinking in one domain does not necessarily transfer to others. However, more recent scholars dealing with these debates often conclude that critical thinking is both a set of skills and disposi- tions (Halpern, 2003; Simpson & Courtney, 2002), and that it is to an extent subject specific, but that there are also aspects of critical thinking that can cross disciplinary boundaries (Brook- field, 2012; Gambrill, 2012; Halpern, 2003; Nosich, 2005). Technical understandings of critical thinking have also come under fire from the quarters of feminist and cultural studies (Norris, 1995). According to critics, a technical approach to critical thinking is inherently tied to western logocentric con- ceptions of rationality that exclude feminist ways of knowing (Thayer-Bacon, 1000; Walters, 1994(b); Warren, K. 1994) and knowledges of non-Western cultures (Norris, 1995; Thayer- Bacon, 2000). Critics from critical theory and critical pedagogy suggest that the technical approach to critical thinking fails to provide an adequate normative dimension, a sense of the in- herently political goals of critical thinking (Giroux, 1994; McLaren, 1994; Kaplan, 1994; Warren, T. 1994). These cri- tiques have spawned the second and third waves of critical thinking scholarship and will be discussed further below. Open Access 23  R. KAHLKE, J. WHITE Technical Critical Thinking in the Health Sciences As in the broader literature, technical approaches to critical thinking dominate the literature on critical thinking in the health sciences (Morrall & Goodman, 2012; Walthew, 2004; Yanchar et al., 2008). This model of critical thinking takes as its premise that critical thinking is a set of skills that can be taught and learned through a series of rational systems of evi- dence analysis (Yanchar et al., 2008). In the health sciences, technical critical thinking takes on particular characteristics related to the thought processes engaged by health professionals. Most often, it is connected to clinical and diagnostic thinking processes. Critical thinking as clinical or diagnostic thinking is directly linked to terms such as clinical reasoning (Alfaro-Le- Fevre, 2013; Crosby, 2011; Gambrill, 2012; Jones-Devitt & Smith, 2007; Kreiter & Bergus, 2009; Krupat, Sprague, Wol- paw, Haidet, & O’Brien, 2011), clinical judgement (Alfaro- LeFevre, 2013; Brunt, 2005; Gambrill, 2012), clinical decision- making (Aberegg, O’Brien, Lucarelli, & Terry, 2008; Gambrill, 2012; Macpherson & Owen, 2010; Simpson & Courtney, 2002; Worrell & Profetto-McGrath, 2007), diagnostic reasoning (Kru- pat et al., 2011), scientific reasoning, (Gambrill, 2012), problem solving (Gambrill, 2012; Heron, 2006; Jones-Devitt & Smith, 2007; Krupat et al., 2011; Simpson & Courtney, 2002; Worrell & Profetto-McGrath, 2007) and, in the discipline of Nursing, nursing process (Gordon, 2000; Staib, 2003; Worrell & Pro- fetto-McGrath, 2007). All of these terms relate to the process of taking in and eva- luating complex clinical information from a variety of sources, but differ slightly depending on what is being “thought” in critical thinking—whether or not critical thinking requires a “problem,” for example (Simpson & Courtney, 2002)—or the outcome of critical thinking—whether or not critical thinking requires a decision (Martin, 2002). Sometimes these terms are synonymous with critical thinking; at other times distinctions are made. For example, Alfaro-Lefevre suggests that clinical reasoning is a type of critical thinking particular to the clinical context. Simpson and Courtney (2002) posit that problem solv- ing is a decision-focussed process that is not synonymous with critical thinking, but requires critical thinking in order to be done effectively. Although scholars and researchers disagree on the relationship between these terms and critical thinking, there is significant overlap in the literature to the extent that the above terms often appear as almost synonymous with critical thinking (Simpson & Courtney, 2002; Victor-Schmil, 2013). Humanist Critical Thinking McLaren (1994) distinguishes the “second wave” of critical thinking through its “liberal humanist assertion that critical thinking be understood contextually” (p. xii). This understand- ing of critical thinking reacts to “first wave” assertions that critical thinking can be understood as a set of universal and abstract skills or procedures (Walters, 1994a). These assertions, second wave thinkers argue, are inherently linked to dominant western, patriarchal and logocentric ways of knowing (Phelan & Garrison, 1994; Thayer-Bacon, 2000; Walters, 1994a; War- ren, K, 1994). Instead, thinkers of the second wave seek to humanise technical understandings of critical thinking, replac- ing claims to objectivity with subjectivity, abstraction with contextualization and positivist notions of Truth with socially constructed truths. These thinkers see critical thinking as subjective in that “the thinker is always present in the act of thinking, and it is pre- cisely her active participation, with its attendant affective, theoretical, and normative presuppositions, from which any analysis of fair-mindedness must proceed” (Walters, 1994a, p. 2). This understanding of critical thinking often stems from a feminist position that seeks to understand critical thinking through “nonanalytic modes of thinking, such as imagination and empathic intuition, as well as the straightforwardly logical ones defended by conventional critical thinking” (Walters, 1994a, p. 11). In general, scholars in this tradition seek either to overturn or modify dominant discourses about critical thinking which stress the importance (and possibility) of individual ra- tional thought by emphasizing the subjectivity of thought, in- cluding a reclamation of individual creativity (Walters, 1994a) and an understanding that there are multiple ways of thinking and knowing (Thayer-Bacon, 2000). This claim to subjectivity also means that critical thinking is not an abstract process that can claim an objective Truth, but is highly contextual: “just as subjects cannot be separated from the process of thinking, so thinking itself cannot be separated from the context in which it arises” (Walters, 1994a, p. 16). Critical thinking is always a biased activity, predicated on a particular worldview and drawing on particular normative as- sumptions (Paul, 1994; Warren, T, 1994). Thinking takes place in a particular time and place, and under particular social condi- tions. Critical thinking is far from abstract and universal, but is ambiguous, malleable and contextual. As much as humanist critical thinking theorists emphasize the subjectivity and individual creativity of thinking, humanist critical thinking is also often linked to a constructivist episte- mology. The context within which the individual thinks and constructs his or her ways of knowing is a social one. Thus, construction of knowledge is always a social process and can- not be disconnected from the broad social constructs within which it is embedded (Warren, 1994). Thayer-Bacon (2000), in particular, seeks to replace the image of the contemplative, solitary thinker with the image of critical thinking as a quilting bee, where construction of knowledge—or quilts—occurs in a social setting, and where the contributions of individual think- ers—or quilters—may be quite different, but all contribute pieces to the construction of knowledge and ideas and cannot be understood in isolation. In this understanding of thought and knowledge, there is no objective Truth “out there,” but multiple socially produced and co-created truths. Humanist Approaches in the Health Sciences Likewise, in the health sciences, there are calls for the recla- mation of subjectivity, creativity and social constructivist un- derstandings of critical thinking. Humanist approaches to criti- cal thinking often appear under the umbrella of critical or nar- rative reflection, and most often emerge in the disciplines of Social Work (Harrison, 2009) and Nursing (Walthew, 2004), and in initiatives calling for a revival of the humanities in medi- cine and medical education (Cave & Clandinin, 2007; Charon, 2004; Charon et al., 1995; Clandinin & Cave, 2008; Doukas, McCullough & Wear , 2012 ). In particular, calls for an attendance to the creativity and sub- jectivity of critical thinking has long been emphasized as a crucial component of critical thinking in the disciplines of Nursing (Chan, 2012; Brunt, 2005; May, Edell, Butell, Doughty, Open Access 24  R. KAHLKE, J. WHITE & Langford, 1999; Popil, 2011; Scheffer & Rubenfeld, 2000; Staib, 2003; Sorensen & Yankech, 2008; Walthew, 2004; Worrell & Profetto-McGrath, 2007) and Social Work (Gibbons & Gray, 2004; Johnston, 2009; Jones-Devitt & Smith, 2007; Miller, Harnek Hall & Tice, 2009). At times, humanist scholars add a relatively narrow emphasis on creativity to largely tech- nical understandings of critical thinking. When Scheffer and Rubenfeld (2000) replicated Facione’s (1990) Delphi Consen- sus, replacing Facione’s philosophy-experts with experts in Nursing, they found that “nursing experts believe that CT [critical thinking] in nursing includes two more affective com- ponents, ‘creativity’ and ‘intuition’” (p. 357). The addition of these subjective and affective components to the largely objec- tivist understanding of critical thinking replicated from the original Delphi study represents a shift or challenge to that dominant technical understanding of critical thinking. Creativ- ity and intuition, with their attendant ambiguity, are not entirely objective or technical procedures. According to Walthew (2004), nurse educators consider critical thinking a complex process that included rational, logical thinking, reflective of traditional theories of critical thinking, and areas of the affective domain more commonly associated with female ways of thinking and knowing. They particularly empha- sized listening to other people’s points of view, empa- thizing, and sensing. (p. 411) In the health sciences, humanist critical thinking has also been linked to social constructivist understandings of the world (Gibbons & Gray, 2004; Jones, 2006; Miller et al., 2009; Yanchar et al., 2012). As King and Kitchener (1990) have sug- gested in their Reflective Judgment Model, these perspectives view the development of critical thinking as intrinsically con- nected to understanding knowledge as abstract and constructed rather than concrete and certain (Mezirow, 1998). Gibbons and Gray (2004), in particular, advocate for a constructivist under- standing of critical thinking in social work education. In their view, critical thinking, rather than claiming objectivity, is value- laden thinking—much more than common sense. We en- gage with the world and with others and our judgments, conclusions, ideas, and opinions flow from these interac- tions—never from a standpoint of detached objectivity. The importance is, therefore, to make the values, judg- ments and decision-making explicit, rather than to claim that they are not there and to see critical thinking as cru- cial to the process of constructing knowledge, meaning and understanding. (Gibbons & Gray, 2004, p. 37) In other words, for critical thinking scholars in this tradition, critical thinking means understanding that thought and knowl- edge are an active process tied to belief and, hence, bias. The key to critical thinking is in articulating, analyzing and altering the assumptions on which ideas and decisions are based. This emphasis on creativity and contextuality moves clinical think- ing away from popular culture images of health science practi- tioners, particularly physicians, who detach themselves in order to coldly and “clinically” analyze the evidence to obtain a cor- rect diagnoses. Instead, humanist critical thinking suggests that practitioners create knowledge in a social context, within a particular facility and society, with patients and with each other. Additionally, it suggests that there might be multiple “right” answers, and that reasoning and diagnostic processes must be subject to review and revision. More radical understandings of critical thinking in the hu- manist tradition, such as those connected to feminist and con- structivist perspectives, often overlap with emancipatory under- standings of critical thinking. As I have suggested, the three critical thinking traditions that provide the framework for this literature review are not discreet categories, but often overlap and intersect. Thus, some understandings of critical thinking may fall under multiple categories. Scheffer and Rubenfeld’s (2000) articulation of critical thinking in Nursing as a creativity and intuition-enhanced version of the technical understanding of critical thinking found in Facione’s (1990) Delphi study falls simultaneously under technical and humanist approaches to critical thinking. Likewise, Gibbons and Gray’s (2004) look at critical thinking in Social Work education contains humanist critical thinking scholars’ understanding of critical thinking as a creative, constructivist process as well as elements of emanci- patory understandings of critical thinking where thought is always a political project and critical thinking is linked to social justice. Emancipatory Critical Thinking Like humanist approaches to critical thinking, McLaren’s (1994) third wave is often discussed as a reaction to dominant technical discourses about critical thinking. However, this un- derstanding of critical thinking has a long history that has evolved somewhat separately from technical understandings of critical thinking stemming from analytic philosophy. Instead, “third wave” critical thinking is informed by critical pedagogy and critical theory. Critical Thinking and Critical Pedagogy The founders of critical theory—such as Horkheimer, Adorno and Marcuse of the Frankfurt School (Wiggerhaus, 1986)—were interested in how people could be taught to use critical thought to uncover ideological structures and unveil the ways in which they are oppressed (Adorno, 1990; Horkheimer, 1995; Marcuse, 1968). The purpose of this thinking is to illu- minate unjust social structures within capitalism and pave the way for a more just society. In other words, “critical theory’s diagnosis of the social world is inherently a normative enter- prise, since it involves judgments that the world ought not to be as it is, or about what is wrong with it” (Finlayson, 2005, p. 12). Stemming from critical theory, emancipatory critical think- ing has direct links to Paulo Freire’s work on critical con- sciousness, a significant concept within critical pedagogy. Critical consciousness is the reflective process through which people awaken and become aware of their own conditions of oppression (Freire, 1996, 2008). In other words, following the project of critical theory, critical consciousness—a term that Freire often interchanges with “critical thought” or “critical thinking”—is about coming to see the oppressive social hierar- chies and the “systems of class, race, and gender oppression” (McLaren, 1994, p. xi) that support those hierarchies. Emancipatory Critical Thinking Building on Freire’s work, critical pedagogues like bell hooks (2010), Peter McLaren (1994), Henry Giroux (1994, Open Access 25  R. KAHLKE, J. WHITE 2006), and Stephen Brookfield (2012) have entered critical thinking debates in education. The emancipatory understanding of critical thinking is marked by two main distinctions. First, these theorists, like those in the humanist tradition, insist that knowledge is constructed; second, they insist that all thought has a strong normative dimension and that critical thinking must involve analyzing and articulating the thinker’s political goals—usually working toward social justice. Like humanist critical thinking, critical thinking scholars in the emancipatory tradition have objected to the positivist un- dercurrent in technical critical thinking; they argue that knowl- edge is socially constructed and, thus, that critical thinking is always contextual rather than universal (McLaren, 1994). Ac- cording to Giroux (1994), “at the core of what we call critical thinking [in the technical tradition], there are two major as- sumptions that are missing. First, there is a relationship be- tween theory and facts; second, knowledge cannot be separated from human interests, values and norms” (p. 201). Put another way, Giroux is arguing that facts—often thought of as objective knowledge—are not objective, but always stem from theory, a particular constructed frame of reference; in his thinking, the theoretical is thus intimately connected with human assump- tions, values and norms. As McLaren (1994) argues, emancipatory critical thinking theorists are critical of the lack of a strong normative dimension in both technical and humanist traditions. Although, as Brook- field (2012) reminds us, some scholars within the technical tradition have at times articulated a purpose, it has been seen as insufficient to many theorists working in the emancipatory tradition. Technical critical thinkers often see critical thinking’s pupose in maintaining democratic processes—individuals must be able to think critically about arguments made in the public sphere in order to make informed choices that are not com- pelled by propaganda (Brookfield, 2012; Facione, 2011; Thayer-Bacon, 2000). The Delphi Consensus (Facione, 1990) states that the goal of all education is to create citizens who will demonstrate the critical thinking skills and dispositions “which consistently yield useful insights and which are the basis of a rational and democratic society” (p. 2). However, according to emancipatory critical thinking scholars, the failure to articulate what such a society might look like, and the problematic claim to neutrality inherent in technical critical thinking discourses often means that critical thinking in the technical tradition falls into the service of dominant ideologies (Jones-Devitt & Smith, 2007). According to Aronowitz (1998) “the idea of the educator as a disinterested purveyor of ‘objective’ knowledge, the incon- trovertible ‘facts’ that form the foundation of dominant values, is itself a form of ideological discourse” (p. 14). Likewise, McLaren (1994) argues that technical and humanist under- standings of critical thinking do not sufficiently articulate their political project or the role of the thinker in maintaining current social relations. In his words, there is a difference between the second wave liberal hu- manist assertion that critical thinking be understood con- textually (a position that does not sufficiently situate crit- ical thinkers in relationship to their own complicity in re- lations of domination and oppression) and the criticalist [third wave] assertion that one’s intellectual labor must be understood ethicopolitically in the context of a particular political project. (p. xiii). Because they believe that knowledge is not objective and bias is inescapable, critical thinking theorists in this tradition see critical thinking as ideology critique, drawing on critical theory. Critical thinking is then the process of simultaneously analyzing the assumptions or premises that are held at a broad societal level—the assumptions on which ideology is based— and on an individual level—the assumptions on the basis of which individuals make decisions. Understanding and unpack- ing these assumptions opens up possibilities for shifting para- digms or worldviews, rather than accepting ideologically driven assumptions as truths. Though, ironically, the normative goals of emancipatory critical thinking are not always articulated, critical thinking from this tradition has a decidedly anti-ca- pitalist bent, stemming from its Marxist roots as discussed above. Emancipatory Approaches in the Health Sciences The call for emancipatory critical thinking is also present in the health sciences (Brunt, 2005; Ford & Profetto-McGrath, 1994; Getzlaf & Osborne, 2010; Gibbons & Gray, 2004; Jones, 2006; Jones-Devitt & Smith, 2007; Kumagai & Lypson, 2009; Teo, 2011). Morrall and Goodman (2012) write: by ‘critical thinking’ we mean going beyond accepting pre-existing social, professional or economic orders to challenge the very basis of our practices and thinking processes and to engage in critical thinking as exemplified in the works of the Frankfurt School.” (Conclusion, para. 1) This form of critical thinking rests on the assumption that power is unequally distributed in society and that an attendance to paradigms and assumptions on which knowledge is based is required in order to remedy that inequality. Yanchar et al. (2008) propose that critical thinking in the health sciences should in- volve “identification and evaluation of ideas, particularly im- plicit assumptions and values, that guide the thinking, decisions, and practices of oneself and others” (p. 270). This view of critical thinking is particularly evident in the discipline of So- cial Work (Gibbons & Gray, 2004; Jones, 2006; Miller, Tice, & Harnek Hall, 2011; Morley, 2008), but also often appears in Nursing (Ford & Profetto-McGrath, 1994; Nokes, Nickitas, Keida, & Neville, 2005; Morrall & Goodman, 2012). Given that social inequalities often manifest themselves as disparities in health status and access to health care, in order to effectively act as stewards of health, health science students and practitioners have a particular obligation to fight social ine- qualities. Frenk et al.’s (2010) emphasis on the role of health science professionals as change agents in healthcare systems suggests that this understanding of critical thinking might be on the rise. Published in The Lancet, a major journal with a broad focus and broad audience, this report has had a large impact. Recent publications by Getzlaf and Osborne (2005), Gibbons and Gray (2004), Jones-Devitt and Smith (2007), Miller et al. (2011) and Morrall and Goodman (2012) all show the connec- tion between the call for health professionals as advocates for change and the ways in which critical thinking skills can be used to uncover ideological assumptions that perpetuate the system as it is. Summary The term critical thinking has a long history and its meaning Open Access 26  R. KAHLKE, J. WHITE has been contested for the better part of a century. We have highlighted the multiple traditions through which critical thinking can and has been understood. Although the framework proposed by Walters (1994a) and McLaren (1994) offers one way of delineating these traditions, this framework is far from stable or exclusive; Brookfield (2000, 2012), for example, of- fers two alternative ways of understanding the range of aca- demic traditions on which concepts of critical thinking are based. Brookfield’s frameworks significantly overlap both with Walters and McLaren’s framework and with each other. Given that there is no consensus on what defines critical thinking as a construct, as Yanchar et al. (2008) suggest, “no approach [to critical thinking] is likely to be universally ac- cepted or to provide sufficient resources for critical analysis across all fields and under all circumstances” (p. 296). As a result, the conceptual framework presented in this review is loosely held; we will treat critical thinking as an array of “kinds of thinking and styles of reasoning” (Mason, 2009, p. 13) that may change with the context within which it is taken up. We hold that critical thinking can and should be understood differ- ently in different contexts and where there are different goals. The aim of this review is to provide one framework for analyz- ing various perspectives on critical thinking, so that educators might better analyze and articulate their own meanings, as- sumptions and goals when they invite their students to “think critically.” REFERENCES Aberegg, S. K., O’Brien, J. M. Lucarelli, M., & Terry, P. B. (2008). The search-inference framework: A proposed strategy for novice clinical problem solving. Medical Education, 42, 389-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03019.x Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamin, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions af- fecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-ana- lysis. Review of Educational Research, 78, 1102-1134. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0034654308326084 Abu-Dabat, Z. I. (2011). Critical thinking, skills and habits. Journal of Education and Sociology, 2, 28-34. Adorno, T. (1990). Negative Dialectics (E. B. Ashton, Trans.). Taylor & Francis. http://l ib.myilibrary.com?ID=7907 Alfaro-LeFevre, R. (2013). Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment: A practical guide (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: El- sevier Saunders. Aronowitz, S. (1998). Introduction. Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, de- mocracy, and civic courage. In P. Freire (Ed.), Pedagogy of freedom (P. Clarke, Trans.). Lanham, MD: Row man & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. Black, B. (2008). Critical thinking—A definition and taxonomy for Cambridge Assessment: Supporting the validity arguments about critical thinking assessments administered by Cambridge Assessment. Thirty Fourth International Association of Educational Assessment Annual Conference. http://www.iaea.info/documents/paper_2b711dd1c.f Bowell, T., & Kemp, G. (2001). Critical thinking: A concise guide. New York: Routledge. Brookfield, S. D. (2000). Contesting criticality: Epistemological and practical contradictions in critical reflection. Proceedings of the 40th Adult Education Research Conference, Vancouver: University of Bri- tish Columbia. Brookfield, S. D. (2012). Teaching for critical thinking: Tools and techniques to help students question their assumptions. San Fran- cisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Brunt, B. (2005). Critical thinking in nursing: An integrated review. The Journal of Continuing Ed uc at ion in Nursing, 36, 60-67. Cave, M. T., & Clandinin, J. D. (2007). Learning to live with being a physician. Reflective Practice, 8, 75-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14623940601138998 Chan, Z. C. Y. (2012). A systematic review of creative thinking/cre- ativity in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, Advance On- line Publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.09.005 Charon, R. (2004). Narrative and medicine. New England Journal of Medicine, 350, 862-864. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp038249 Charon, R., Banks, J. T., Connelly, J. E., Hawkins, A. H., Hunter, K. M., Jones, A. H., Poirer, S., et al.(1995). Literature and medicine: Contributions to clinical practice. Annals of Internal Medicine, 122, 599-606. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-122-8-199504150-00008 Clandinin, J, D., & Cave, M. T. (2008). Creating pedagogical spaces for developing doctor professional identity. Medical Education, 42, 765-770. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03098.x Crosby, K. (2011). The role of certainty, confidence, and critical think- ing in the diagnostic process: Good luck or good thinking? Academic Emergency Medicine, 18 , 212-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00979.x Doukas, D. J., McCullough, L. B., & Wear, S. (2012). Academic Medi- cine, 87, 334-341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318244728c Ennis, R. H. (1962). A concept of critical thinking. Harvard Educa- tional Review, 32, 81-111. Ennis, R. H. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarifi- cation and needed research. Educational Researcher, 18, 4-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018003004 Ennis, R. H. (1990). The extent to which critical thinking is subject- specific: Further clarification. Educational Researcher, 19, 13-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019004013 Epstein, R. L. (2003). The pocket guide to critical thinking (2nd ed). Toronto, CA: Wadsworth Group. Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consen- sus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction (Research Report). Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press. http://assessment.aas.duke.edu/documents/Delphi_Report.pdf Facione, P. A. (2011). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. (Research Report). Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press. http://www.student.uwa.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1922502/ Critical-Thinking-What-it-is-and-why-it-counts.pdf Finlayson, J. G. (2005). Habermas: A very short introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780192840950.001.0001 Fischer, S. C., Spiker, A., & Riedel, S. L. (2009). Critical thinking training for army officers volume two: A model of critical thinking (Research Report). US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Science. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/235083753_Critical_Thinki ng_Training_for_Army_Officers._Volume_2_A_Model_of_Critical_ Thinking Ford, J. S., & Profetto-McGrath, J . (1994). A model for critical thinking within the context of curriculum as praxis. Journal of Nursing Edu- cation, 33, 341-344. Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramon, Trans.). Toronto, CA: Penguin Books. Freire, P. (2008). Education for critical consciousness. New York: Con- tinuum. Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Zurayk, H. et al. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interde- pendent world. The Lancet, 376, 1923-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 Gambrill, E. (2012). Critical thinking in clinical practice: Improving the quality of judgments and decisions (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Garrison, D. R. (1992). Critical thinking and self-directed learning in adult education: An analysis of responsibility and control issues. Adult Education Quarterly, 42, 136-148. Open Access 27  R. KAHLKE, J. WHITE Getzlaf, B. A., & Osborne, M. (2010). A journey of critical conscious- ness: An educational strategy for health care leaders. International Journal of Nursing Educational Scholarshihp, 7, 1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.2202/1548-923X.2094 Gibbons, J., & Gray, M. (2004). Critical thinking as integral to social work practice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 24, 19-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J067v24n01_02 Giroux, H. (1994). Toward a pedagogy of critical thinking. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New perspectives on critical thinking (pp. 199-204). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Giroux, H. A. (2006). Youth, higher education, and the crisis of public time. In H. A. Giroux (Ed.), The Giroux reader (pp. 199-204). Boul- der, CO: Paradigm Publishers. Gordon, J. M. (2000). Congruency in defining critical thinking by nurse educators and non-nurse scholars. Journal of Nursing Education, 39, 340-351. Halpern, D. (2003). Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Harrison, K. (2009). “Listen: This really happened”: Making sense of social work through story-telling. Social Work Education, 28, 750- 764. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02615470802535755 Heron, G. (2006). Critical thinking in social care and social work: Searching student assignments for the evidence. Social Work Education, 25, 209-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02615470600564965 Hooks, B. (2010). Teaching critical thinking: Practical wisdom. New York: Routledge. Horkheimer, M. (1995). Critical Theory: Selected essays. New York: Continuum. Johnston, L. B. (2009). Critical thinking and creativity in a social work diversity course: Challenging students to “think outside the box”. Journal of Human Behaviour in the Social Environment, 19, 646-656. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10911350902988001 Jones, S. (2006). A journey of seven steps—Social work students as critical thinkers. Special Education, 1, 48-54. Jones-Devitt, S., & Smith, L. (2007). Critical thinking in health and social care. London: Sage Publication s . Kaplan, L. D. (1994). Teaching intellectual autonomy: The failure of the critical thinking movement. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New perspectives on critical thinking (pp. 205-220). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. King P. M., & Kitchner. K. S. (1990). The reflective judgment model: Transforming assumptions about knowing. In A. B. Knox (Ed.), Fos- tering critical reflection in adulthood (pp. 159-176). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Kreiter, C. D., & Bergus, G. (2009). The validity of performance-based measures of clinical reasoning and alternative approaches. Medical Education, 43, 320-325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03281.x Krupat, E., Sprague, J. M., Wolpaw, D., Haidet, P., & O’Brien, B. (2011). Thinking critically about CT: Ability, disposition or both? Medical Education, 45, 625-635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03910.x Kumagai, A. K., & Lypson, M. L. (2009). Beyond cultural competence: Critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Academic Medicine, 84, 782-787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398 Lipman, M. (1988). Critical thinking—What can it be? Educational Leadership, 45, 38- 43. Macpherson, K., & Owen, C. (2010). Assessment of critical thinking ability in medical students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Edu- cation, 35, 45-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930802475471 Marcuse, H. (1968). Negations: Essays in critical theory (J. J. Shapiro, Trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press. Martin, C. (2002). The theory of critical thinking in nursing. Nursing Education Perspectives, 23, 243-247. Mason, M. (2009). Critical thinking and learning. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley- Blackwell. May, B. A., Edell, V., Butell, S., Doughty, J., & Langford, C. (1999). Critical thinking and clinical competence: A study of their relation- ship in BSN seniors. Journal of Nursing Education, 38, 100-110. McLaren, P. (1994). Foreword: Critical thinking as a political project. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New perspectives on critical thinking (pp. ix-xv). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. McPeck, J. E. (1990). Critical thinking and subject specificity: A reply to Ennis. Educational Researcher, 19, 10-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019004010 McPeck, J. E. (1994). Critical thinking and the “trivial pursuit” theory of knowledge. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New per- spectives on critical thinking (pp. 101-118). Albany, NY: State Uni- versity of New York Press. Mezirow, J. (1998). On critical reflection. Adult Education Quarterly, 48, 185-198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/074171369804800305 Miller, S. E., Harnek Hall, D. M., & Tice, C. J. (2009). Assessing criti- cal thinking: The use of literature in a policy course. The Journal of Baccelaureate Social Work, 14, 89-104. Miller, S. E., Tice, C. J., & Harnek Hall, D. M. (2011). Bridging the explicit and implicit curricula: Critically thoughtful critical thinking. The Journal of Baccelaureate Social Work, 16, 33-45. Missimer, C. (1994). Why two head are better than one. Philosophical and pedagogical implications of a social view of critical thinking. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New perspectives on critical thinking (pp. 119-133). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Morely, C. (2008). Teaching critical practice: Resisting structural do- mination through critical reflection. Social Work Education, 27, 407- 421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02615470701379925 Morrall, P., & Goodman, B. (2013). Critical thinking, nurse education and universities: Some thoughts on current issues and implications for nursing practice. Nurse Education Today. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.11.011 Nokes, K. M., Nickitas, D. M., Keida, R., & Neville, S. (2005). Does service-learning increase cultural competency, critical thinking, and civic engagement? Journal of Nu rse Education, 44, 65-70. Norris, S. P. (1995). Sustaining and responding to charges of bias in critical thinking. Educational Theory, 45, 199-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.1995.00199.x Nosich, G. (2005). Learning to think things through: A guide to cri- tical thinking across the curriculum (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31, 204-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002 Scheffer, B. K., & Rubenfeld, M. G. (2000). A consensus statement on critical thinking in nursing. Joural of Nursing Education, 39, 352- 359. Simpson, E., & Courtney, M. (2002). Critical thinking in nursing edu- cation: Literature review. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 8, 89-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172x.2002.00340.x Sorensen, H. A. J., & Yankech, R. (2008). Precepting in the fast lane: Improving critical thinking in nurse graduates. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 39, 208-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20080501-07 Staib, S. (2003). Teaching and measuring critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 42, 498-508. Teo, T. (2011). Radical philosophical critique and critical thinking in psychology. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 31, 193-199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024708 Thayer-Bacon, B. J. (2000). Transforming critical thinking: Thinking constructively. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Thomson, A. (2001). Critical Reasoning: A practical introduction. Florence, KY: Routle dge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203470510 Tishman, S., Jay. E., & Perkins, D. N. (1993). Teaching thinking dis- positions: From transmission to enculturation. Theory into Practice, 32, 147-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00405849309543590 Victor-Chmil, J. (2013). C riti cal thinking versus cl inical reasoning versus clinical judgement. Nurse Educator, 38, 34-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0b013e318276dfbe Walters, K. S. (1994a). Introduction: Beyond logicism in critical thinking. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New perspectives in Open Access 28  R. KAHLKE, J. WHITE Open Access 29 critical thinking (pp. 1-22). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Walters, K. S. (1994b). Critical thinking, rationality, and the vulcanize- tion of students. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New perspectives on critical thinking (pp. 61-80). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Walthew, P. J. (2004). Conceptions of critical thinking held by nurse educators. Journal of Nurse Education, 43, 408-411. Warren, K. J. (1994). Critical thinking and feminism. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New perspectives on critical thinking (pp. 199-204). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Warren, T. H. (1994). Critical thinking beyond reasoning: Restoring vir- tue to thought. In K. S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New per- spectives on critical thinking (pp. 221-232). Albany, NY: State Uni- versity of New York Press. Wiggershaus, R. (1995). The Frankfurt School: Its history, theories and political significance. M. Robertson (Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Polity Press. Worrell, J. A., & Profetto-McGrath, J. (2007). Critical thinking as an outcome of context-based learning among post RN students: A lit- erature review. Nurse Education Today, 27, 420-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2006.07.004 Yanchar, S., Jackson, A., Hansen, K., & Hansen, J. (2012). Critical thinking in applied psychology: Toward and edifying view of critical thinking in applied psychology. Issues in Religion and Psychotherapy, 34, 69- 80. Yanchar, S. C., Slife, B. D., & Warne, R. (2008). Critical thinking in d is- ciplinary practice. Review of General Psychology, 12, 265-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.12.3.265

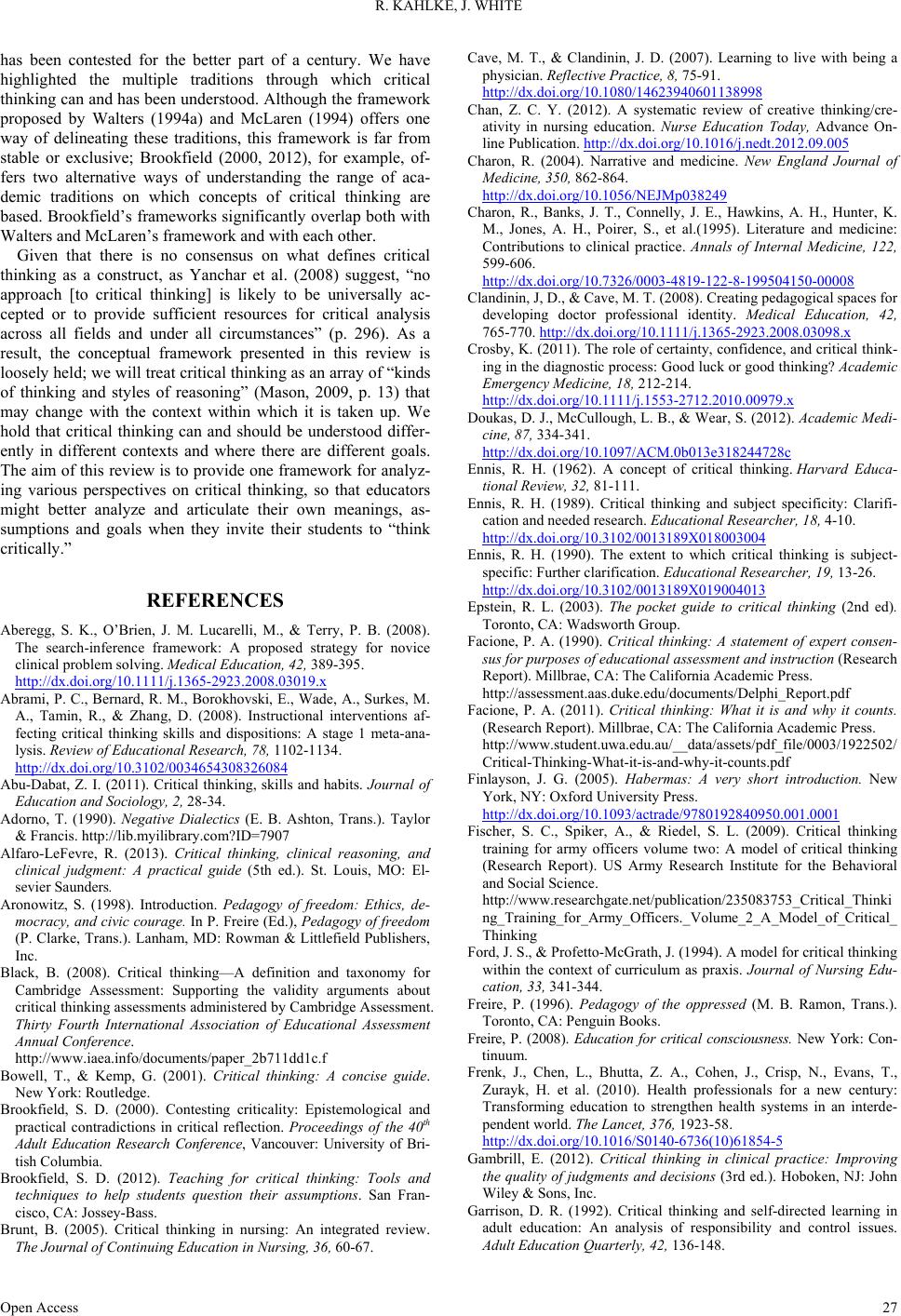

|