Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.12, 1039-1045 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.412151 Open Access 1039 The Contributions of Attachment and Caregiving Orientations to Living a Meaningful Life Abira Reizer1*, Dana Dahan2, Phillip R. Shaver3 1 Department of Behavioral Sciences, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel 2Ruppin College, Emek Hefer, Israel 3University of California, Davis, USA Email: *abirar@ariel.ac.il Received October 22nd, 2013; revised November 23rd, 2013; accepted December 19th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Abira Reizer et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Abira Reizer et al. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. This study adopted Bowlby’s (1982) behavioral systems perspective on meaning in life by focusing on two behavioural systems discussed by Bowlby: attachment and caregiving. Three hypotheses were for- mulated: 1) attachment orientations will predict meaning in life; 2) caregiving orientations will predict meaning in life; 3) attachment will moderate the associations between caregiving and sense of meaning in life. Three hundred thirteen adults completed self-report scales measuring attachment, caregiving, and two aspects of meaning in life (presence of meaning and searching for meaning). Results indicated that at- tachment insecurities (anxiety and avoidance), caregiving deactivation, and the interaction between at- tachment anxiety and caregiving deactivation contributed uniquely to the prediction of meaning in life. In addition, religiosity contributed significantly to the presence of meaning. Finally, attachment anxiety and caregiving deactivation predicted searching for meaning. The study shows that a behavioral systems per- spective can contribute to the literature on meaning in life. Keywords: Attachment; Caregiving; Meaning in Life The Contributions of Attachment and Caregiving Orientations to Living a Meaningful Life “Meaning in life” refers to the web of connections, under- standings, and interpretations that help people comprehend their experiences and formulate plans that direct their energies to- ward the achievement of a desired future (Steger, 2009). The significance of meaning in life for positive psychological states and effective functioning has been repeatedly demonstrated (e.g., Reker, 2005; Steger, 2012).The present article explores conceptual and empirical links between research on meaning in life and the behavioral systems perspective presented in Bow- lby’s (1982) work on attachment and loss. Bowlby based his theory on a premise, derived from ethol- ogy, that human beings are born with a number of innate be- havioral systems (such as attachment, caregiving, exploration, and sex). A behavioral system is a collection of goal-oriented behaviors that serve a particular function, such as protection from threats or successfully rearing offspring. In the case of human beings, who survive in the context of groups of intelli- gent and verbally communicating family and community mem- bers, the behavioral systems contribute to the meaningful or- ganization of life, allowing goals to be pursued and approached in a coherent way. Specifically, maximizing the efficiency of one’s daily efforts to survive, acquiing skills and resources, and achieving important evolutionary goals can contribute signifi- cantly to a person’s sense of meaning in life. This study focuses on two social-relational behavioral sys- tems: attachment and caregiving. The attachment system con- tributes to survival by motivating children and adults to seek protection and comfort in times of threat or distress. This is especially important during early childhood, because human infants are born without the capacity to protect themselves, feed themselves, or learn important survival skills. But attachment processes are also important throughout life, because humans continue to be interdependent and to rely on each other at all ages. According to Bowlby (1982), the same way that the at- tachment system evolved as a care-seeking system, a caregiving behavioral system evolved as a complement to others’ attach- ment systems. The caregiving system contributes, primarily, to the survival of kin and biologically related community mem- bers, but it can be applied more broadly to other forms of com- passion and caring. Bowlby conceptualized the caregiving sys- tem as an inborn, generally functional response to a needy other’s wish for protection or assistance (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Recently, preliminary attempts have been made to ex- amine the possible contribution of the attachment system to attaining a sense of meaning in life (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2012). The present study expands this line of research by examining the unique contributions of the caregiving system to establishing a meaningful life as well as examining the interplay between the attachment and caregiving *Corresponding author.  A. REIZER ET AL. systems. Individual Differences in Functioning of the Attachmen t a n d Caregiving Behavioral Systems Although all human beings are assumed to possess attach- ment and caregiving behavioral systems, there are differen- ces—probably genetically and experientially based—between individuals in the ways the systems operate (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Based on Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, and Wall’s (1978) pioneering research, self-report measures have been de- veloped to assess two forms of attachment insecurity in adult- hood: anxiety and avoidance (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). Scores on measures of these two dimensions are related to a wide variety of measures of relationship quality and mental health, as indicated in hundreds of published studies (see Miku- lincer & Shaver, 2007, for an extensive review). In particular, previous studies provide strong evidence for the contribution of attachment security (indicated by low scores on measures of attachment anxiety and avoidance) to generally positive and constructive cognitions, emotions, and behaviors. For example, secure individuals hold more optimistic expecta- tions about their ability to handle stress (e.g., Berant, Mikulin- cer, & Florian, 2001), attachment security is associated with self-report measures of joy and happiness (e.g., Magai, Hun- ziker, Mesias, & Culver, 2000) and with having a sense of meaning and coherence in life (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005). Individual differences in the operation of the caregiving be- havioral system have been less thoroughly studied (although see Kunce & Shaver, 1994, for early efforts, and Collins & Ford, 2010, for recent studies). Shaver, Mikulincer, and She- mesh-Iron (2009) have conceptualized individual differences in caregiving orientations in terms of a two-dimensional space similar to the one defined by attachment anxiety and avoidance. The first dimension of the space is labelled “deactivation” of the caregiving system, It refers to the extent that people are relatively less sensitive and responsive to others’ needs and more likely to dismiss or downplay their distress. People who are deactivating caregivers tend not to be empathic and tend to distance themselves from others when care and support are needed or requested. In contrast, “hyperactivation” of the care- giving system includes tendencies to exaggerate others’ needs and wishes for help, exaggerate empathy and willingness to help, or insist on helping, even intrusively, whether involve- ment is desired or not. Caregiving deactivation and hyperacti- vation are negatively associated with self-reports of empathy, compassion, and altruism, and with observational measures of caregiving behavior (Shaver et al., 2009). Recent research suggests that genuine, non-deactivating and non-hyperactivating care benefits the caregiver in addition to benefitting the care recipient (Kim, Carver, Deci, & Kasser, 2008; Kogan et al., 2010). Caregiving can enhance feelings of accomplishment, kindness, and moral goodness on behalf of the care provider (something that Erikson, 1993, labeled “generate- vity”) and enhance his or her sense of meaning in life (Farran, et al., 1999). Research (Impett, Gable, & Peplau, 2005) has shown that members of couples who show genuine concern for his or her partner’s wellbeing on a daily basis receive both per- sonal benefits (e.g., personal fulfilment) and interpersonal ben- efits (e.g., a strengthened relationship), whereas egoistic mo- tives interfere with these benefits. Dimensions of Meaning in Life Meaning in life refers to “the extent to which people com- prehend, make sense of, or see significance in their lives, ac- companied by the degree to which they perceive themselves to have a purpose, mission, or over-arching aim in life” (Steger, 2012). It has been suggested that the creation of a worldview and the ascription of meaning to events is not rationally based on external events or conditions but, instead, derives from one’s mental representation of experiences (Marris, 1996). Although the presence or absence of meaning in life has received consid- erable research attention, the degree to which people search for meaning has not received the same amount of empirical scru- tiny. The search for meaning includes establishing or augment- ing the perceived meaning, significance, and purpose of one’s life (Steger, 2012; Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan, & Lorentz, 2007).The presence of meaning and the search for meaning are quite different. Whereas the presence of meaning in life corre- lates positively with other positive psychological characteristics (e.g., love, joy, extraversion, agreeableness, efficacy, self-worth; see Kashdan & Steger, 2007; Stillman et al., 2009), the search for meaning tends to correlate with measures of neuroticism and negative emotional states or traits, such as anxiety and de- pression. Furthermore, people who report searching for mean- ing tend to have less reported meaning in their lives (Steger et al., 2006). Previous studies have indicated the importance of close rela- tionships as one of the life goals that enhance personal meaning (Doyson et al., 1997; Emmons, 2003), and social exclusion and ostracism have been associated with reduced feelings of mean- ing and purpose in life (Stillman et al., 2009). These research findings are in line with Martin Buber’s writings (see Stewart, 2011) about the importance of “I-thou” relationships for mean- ing and life satisfaction. The Present Study From an attachment perspective, the ability to seek and ob- tain emotional support from others (attachment security) would be expected to relate to having a solid sense of life’s value and meaning, because a secure individual should be able to make the most of close relationships and develop positive views of self. In contrast, attachment insecurity (avoidance or anxiety) may render a person susceptible to threats of meaninglessness and cause him or her to engage in a search for meaning (Bod- ner , Bergman & Cohen-Fridel, 2013; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005). Therefore it can be hypothesized that lower levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance (indicating greater attach- ment security) would be associated with higher levels of mean- ing in life and lower levels of searching for meaning. With regard to the other behavioral system under investiga- tion here, it has often been claimed that meaning in life is most fully achieved when people engage in pursuits that transcend their own immediate self-interests (Steger, 2009), dedicate their talents to something beyond themselves (Seligman, 2002), and experience greater degrees of self-transcendence or genera- tively (Emmons, 2003). On the other hand, when people lack empathy and perceive others as a burden (characteristics of caregiving deactivation), or get so involved in trying to help others who may not want their support (as happens in cases of caregiving hyperactivation), they may be less likely to feel that life is meaningful. Therefore it can be hypothesized that lower levels of caregiving hyperactivation and deactivation would be Open Access 1040  A. REIZER ET AL. associated with higher levels of meaning in life and lower lev- els of searching for meaning. In light of Bowlby’s (1982) theoretical writings, Shaver and Mikulincer (2002) suggested that when attachment needs have been largely met, people are able to turn their attention to other behavioral systems, such as caregiving. Caregiving, in particu- lar, may not be activated when caregivers’ own feelings of security are threatened. Hence, attachment security (whether chronic or temporary) should facilitate responsive caregiving, whereas insecurity should impede it. Based on this theoretical argument it can be hypothesized that the attachment insecurity scores would moderate the association between the caregiving and meaning in life scores. Specifically, the caregiving orienta- tions would contribute to meaning in life mainly for those who scored relatively low on attachment anxiety and avoidance. Furthermore, one of the purposes of this study was to inves- tigate whether the associations between attachment, caregiving, and meaning in life appear when demographic characteristics are statistically controlled. Religion is a common demographic predictor of meaning in life. Religion offers an answer to one of life’s mysteries: “Why am I here?” Religious people tend to feel that their lives matter, are understandable, and have a pur- pose or mission (Steger, 2012; Stroope, Draper, & Whitehead, 2012). Previous research has also shown that couple and family relationships can protect a person’s sense of meaning, and this may be the motivation for marriage and having children, par- ticularly (Scannell, 2009), though not all studies support this idea (e.g., Hansen, 2012; Peterson, Park & Seligman, 2005). Age and gender were also included as control variables, al- though they have yielded contradictory results in previous re- search (e.g., Crumbaugh, 1968; Debats, 1998; Reker, Peacock, & Wong, 1987; Scannell, 2009; Steger et al., 2006). Method Participants The sample consisted of 313 Israeli adults (42% men and 58% women), whose ages ranged from 18 to 69 (M = 36.4, SD = 11.6); 70% viewed themselves as nonreligious; and 58.5% were married or were living with a significant other. The mar- ried participants had an average of 2.67 children (SD = 1.30). Their average years of education was Mean = 14.56, SD = 2.54, Median = 15. Materials Attachment insecurity measurements. Attachment anxiety and avoidance were assessed with a Hebrew version of the Experiences in Close Relationships scales (ECR; Brennan et al., 1998). Participants rated the extent to which each item was descriptive of their experiences in close relationships on a 7-point scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much (7). The reliability and validity of the scale have been repeatedly dem- onstrated (beginning with Brennan et al., 1998; see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007, for a more recent review). In the current study, attachment dimensions were assessed with a short 18-item version of the ECR, previously used by Ronen and Mikulincer (2009). Cronbach’s α was .85 for the attachment anxiety items and .78 for the avoidance items. As expected based on previous research, the two scores were not highly correlated, r(312) = 0.19, p < 0.01, indicating that they are different constructs. On this basis, attachment anxiety and avoidance scores were com- puted for each participant by averaging the relevant items. Caregiving orientations. Caregiving orientations were meas- ured with a 20-item self-report instrument designed by Shaver et al. (2009) to measure caregiving-related deactivation and hyperactivation. Participants were asked to read each item and rate the extent to which it described their attitudes, feelings, beliefs, and motives in social interactions. Ratings were made on a 7-point scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much (7); 10 items tapped caregiving hyperactivation (e.g., “When I don’t succeed in helping another person, I feel useless” or “Some- times I feel I force help on another person”), and 10 items tapped caregiving deactivation (e.g.,“Sometimes I feel that helping others is a waste of time”). Cronbach alphas were .87 for caregiving hyperactivation and .91 for caregiving deactiva- tion. Shaver et al. (2009) provided extensive evidence on the reliability, two-factor structure, convergent, discriminate, and predictive validity for the scale. Meaning in life dimensions. The Meaning in Life Question- naire (MLQ; Steger et al., 2006) assesses the extent to which respondents feel that their lives are meaningful (measured by the MLQ-presence subscale) and the extent to which they are actively seeking meaning in their lives (measured by the MLQ-search subscale). Each subscale contains five items rated on a scale ranging from absolutely untrue (1) to absolutely true (7). Both subscales have been shown to have good internal consistency, test-retest stability, and validity (e.g., Steger et al., 2006). In the present study, Cronbach’s α was .91 for the MLQ-P and .88 for the MLQ-S. Procedure The participants were recruited informally and agreed to par- ticipate in the study without monetary reward. They completed the measures online. Results Preliminary Analyses Descriptive statistics for each of the measures are shown in Table 1. Avoidant attachment was positively associated with caregiving deactivation, and anxious attachment was positively associated with caregiving hyperactivation, indicating that the two systems are related, as was also found by Kunce and Shav- er (1994). (This association is expected, because both systems are expected to be influenced by previous interactions with attachment figures). As predicted, the caregiving and attach- ment scales were negatively correlated with the presence of meaning in life. In contrast, attachment anxiety and caregiving hyperactivation were positively associated with higher levels of searching for meaning. Although the correlations supported research hypotheses H1 and H2, they are modest in size. Unique Contri buti on of C ar e gi vi n g and Att achme nt to Meaning of Life To determine the unique contributions of the caregiving and attachment variables to meaning in life, two hierarchical re- gression analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21 for windows. The dependent variables were meaning in life (MLQ- P and the MLQ-S). In the first step of each regression, the con- trol variables: age, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), having chil- dren (0 = childless, 1 = having children), marital status (0 = not Open Access 1041  A. REIZER ET AL. Open Access 1042 Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations. MeanSD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1) Attachment avoidance 3.121.11 1 2. Attachment anxiety 3.451.34 0.19** 1 3) Caregivng deactivation 2.621.17 0.32*** 0.33*** 1 4) Caregiving hyperactivation 3.261.19 0.19** 0.56*** 0.36*** 1 5) MLQ-P 25.677.14 −0.24*** −0.35*** −0.47*** −0.25*** 1 6) MLQ-S 21.238.26 0.06 0.35*** −0.01 0.19** −0.01 1 7) Age 36.4211.64 −0.02 −0.28*** −0.12* −0.17**0.16** −0.061 8) Having children - - −0.00 −0.27*** −0.12* −0.11 0.30*** −0.070.63*** 1 9) Marital status - - −0.03 −0.17** −0.07 −0.01 0.19** −0.090.32*** 0.47*** 1 10) Gender - - −0.19** 0.07 −0.16** −0.08 0.08 0.02 −0.21*** −0.11* −0.031 11) Religious - 0.06 0.03 0.07 0.07 0.21*** −0.03 −0.08 0.15** 0.08 0.07 Notes: Dummy variables were used for gender (with 0 = male and 1 = female), for marital status (with 0 = not married and 1 = married), for having children (0 = childless and 1 = having children), and for being religious (with 0 = no and 1 = yes). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. married, 1 = married) and religiosity (0 = no, 1 = yes) were entered into the regression equation. In the second step, at- tachment and caregiving scores were entered into the regression equation. In the third step interactions between the attachment and caregiving variables were entered into the regression equa- tion (see Table 2). The hierarchical regression analysis with MLQ-P as the dependent variable was significant F(13,284) = 13.48, p < 0.001 and accounted for 38.5% of the variance in meaning in life with the attachment and caregiving variables accounting for most of the variance (25%). There were signifi- cant unique effects of deactivated caregiving (β = −0.43, p < 0.001), attachment anxiety (β = −0.15, p < 0.05), attachment avoidance (β = −0.12, p < 0.05) and religiosity (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), and there was a significant interaction between attach- ment anxiety and caregiving deactivation (β = 0.13, p < 0.05). The hierarchical regression analysis with MLQ-S as the de- pendent variable was significant (F(13,284) = 4.33, p < 0.001) and accounted for 16% of the variance in searching for meaning in life, with attachment anxiety (β = 0.40, p < 0.001) and care- giving deactivation (β = 0.13, p < 0.05) accounting for most of the variance (14%). Testing the Moderation Hypoth esis As mentioned above, there was a significant interaction be- tween attachment anxiety and caregiving deactivation in pre- dicting meaning in life (MLQ-P) (β = 0.13, p < 0.05). The rela- tion between deactivating caregiving and perceived meaning in life at two levels of attachment anxiety was examined using the Aiken and West (1991) method for evaluating moderation. This analysis indicated that the association between caregiving deac- tivation and the presence of meaning in life was higher for peo- ple who were lower in anxiety (β= −0.58, p < 0.001) than for those who were higher in anxiety levels (β = −0.30, p < 0.001 respectively). As shown in Figure 1, when caregiving deactiva- tion was high, meaning in life was relatively low regardless of attachment anxiety level, but when caregiving deactivation was low, being high in attachment anxiety contributed to lower meaning in life. Discussion The experience of meaning in life is a fundamental aspect of human wellbeing (Frankl, 1963; Steger, 2009). The present study confirms, as expected theoretically, that attachment secu- rity—the opposite of anxiety and avoidance—is associated with having a sense of meaning in life. In support of H1 and in line with previous studies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005; Bonder et al., 2013), the current study indicates that low levels of anxiety and avoidance are positively associated with presence of mean- ing in life. However, meaning in life is also associated with more secure forms of caregiving—the opposite of deactivated or hyperactivated caregiving. These effects were retained when age, gender, religiosity, and having children were statistically controlled, even though meaning in life was correlated with all of these variables except gender. In line with H3, these results support previous work that suggest that meaning in life is most fully achieved when people dedicate their talents to something beyond themselves (Seligman, 2002; Steger, 2009). As ex- pected, searching for life’s meaning was associated signifi- cantly with attachment anxiety, suggesting that the feeling of needing to search for security in close relationships with other people is connected with a similar desperate search for secure meaning in life as indicated previously (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005). No demographic variables were significantly associated with searching for life’s meaning. Also, in accordance with H3 and in line with Shaver and Mikulincer’s (2002) theoretical model, the findings suggest that attachment can moderate care- giving orientations. The pattern of the significant interaction between deactivated caregiving and attachment anxiety sug- gests that anxiety level does not affect meaning in life very much in the presence of highly deactivated caregiving. Mean- ing is at its lowest when caregiving is deactivated, whether attachment anxiety is present or not. But when caregiving deac- tivation is low—that is, when a person is open and ready to care for another person—being anxious about attachment interferes with finding meaning. In a practical sense, these results suggest that a person who finds life less meaningful than average might be helped by encouragement to get involved in helping others. But in the process of making this change (that is, becoming more activated with respect to caregiving), it would be impor- tant not to engage in caregiving in a desperate or needy (i.e., anxious and intrusive) way. The fact that hyperactivated caregiving lost its significant association with meaning in life when it was entered into a  A. REIZER ET AL. Table 2. Standardized regression coefficients predicting meaning in life. Variable Variable MLQ-P MLQ-S Step 1 Age 0.04 −0.09 Gender 0.09 0.01 Religiosity 0.15* −0.05 Marital status 0.09 −0.09 Having children 0.21* 0.05 ∆ R² 0.11*** 0.01 Step 2 Age −0.01 −0.03 Gender −0.02 −0.01 Religiosity 0.18** −0.06 Marital status 0.08 −0.07 Having children 0.10 0.10 Attachment anxiety −0.19** 0.41*** Attachment avoidance −0.12* 0.03 Caregiving hyperactivation −0.02 0.03 Caregiving deactivation −0.39*** 0.15* ∆ R² 0.25*** 0.14*** Step 3 Age −0.01 −0.02 Gender −0.04 0.01 Religiosity 0.21*** −0.05 Marital status 0.09 −0.07 Having children 0.08 0.10 Attachment anxiety −0.15* 0.40*** Attachment avoidance −0.12* 0.01 Caregiving hyperactivation −0.04 0.06 Caregiving deactivation −0.43*** 0.13* AAvo* CDe −0.01 0.01 AAnx* CHyper 0.06 −0.02 AAnx* CDe 0.13* −0.07 AAvo* CHyper −0.03 −0.05 ∆ R² 0.03 0.01 Total R² 0.385 0.16 Total F 13.48*** 4.33*** Notes: AAvo = attachment avoidance; AAnx = attachment anxiety; CDe = caregiving deactivation; CHyper = caregiving hyperactivation. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Figure 1. Attachment anxiety moderates the association between caregiving deactivation and the presence of mean- ing in life. Open Access 1043  A. REIZER ET AL. regression analysis with attachment anxiety (as predictors of meaning in life) suggests that the significant correlation be- tween hyperactivated caregiving lower meaning in life (r = 0.25, in Table 1) was a reflection of attachment anxiety, which cor- related (r = 0.56) with hyperactivated caregiving. In other words, providing another person with attention, care, and sup- port to facilitate the desperate search for appreciation and vali- dation is a consequence of attachment anxiety. Thus, simply advising people to increase their sense of meaning in life by caring for others might be misleading if the form of care they provided was anxious, intrusive, and overly self-focused. Limitations and Conclusion Limitations of the present study include the use of a conven- ience sample and a cross-sectional design that does not allow strong inferences about causality. It is possible that gaining a sense of meaning in life might increase a person’s sense of security without necessitating a change in one’s behavior in close relationships (see Davila & Sargent, 2003). Moreover, the results of this study were based on self-report questionnaires that may have been influenced by perceptual biases and the inclination to provide socially desirable responses. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies take a longitudinal approa- ch. Despite the limitations of this exploratory study, research findings support the idea that meaning in life is enhanced by attachment security and providing responsive, nonintrusive care to others. The findings fit with the views of traditional human- istic psychologists who stressed the importance of “Being-love” (Maslow, 1971) and compassionately taking on others’ suffer- ing. Research findings also support the views of Victor Frankl (1963), who claimed that through their love people can enable their beloved to find meaning, and by doing so, gain an en- hanced sense of life’s meaning. REFERENCES Bruce, V., Young, A., Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situa- tion. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Berant, E., Mikulincer, M., & Florian, V. (2001). Attachment style and mental health: A 1-year follow-up study of mothers of infants with congenital heart disease. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 956-968. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278004 Bodner, E., Bergman, Y. S., & Cohen-Fridel, S. (2013). Do attachment styles affect the presence and search for meaning in life? Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 1-19. Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books. Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report meas- urement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close rela- tionships (pp. 46-76). New York: Guilford Press. Collins, N. L., & Ford, M. B. (2010).Responding to the needs of others: The caregiving behavioural system in intimate relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 235-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360907 Crumbaugh, J. C. (1968). Cross-validation of a purpose-in-life test based on Frankl’s concepts. Journal of Individual Psychology, 24, 74-81. Davila, J., & Sargent, E. (2003). The meaning of life (events) predicts change in attachment security. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1383-1395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167203256374 Dyson, J., Cobbs, M., & Forman, D. (1997). The meaning of spiritual- ity: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26, 1183- 1188. Debats, D. L. (1998). Measurement of personal meaning: The psycho- metric properties of the Life Regard Index. In P.T.P. Wong & P.S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning (pp. 237-260). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Emmons, R. A. (2003). Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Well- springs of a positive life. In C. L. M. Keyes, & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 105- 128). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10594-005 Erikson, E. H. (1950/1993). Childhood and society. New York: Norton. Farran, C. J., Miller, B. H., Kaufman, J. E., Donner, E., & Dogg, L. (1999).Finding meaning through caregiving: Development of an in- strument for family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55, 1107-1125. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199909 )55:9%3c%3e1.0.CO;2-F/issuetoc http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199909)55:9<1107::AID- JCLP8>3.0.CO;2-V Frankl, V. E. (1963). Man’s search for meaning. New York: Washing- ton Square Press. Haley, W. E., LaMonde, L. A., Han, B., Burton, A. M., & Schonwetter, R. (2003). Predictors of depression and life satisfaction among spousal caregivers in hospice: Application of a stress process model. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 6, 215-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/109662103764978461 Hansen, T. (2012). Parenthood and happiness: A review of folk theories versus empirical evidence. Social Indicators Research, 108, 29-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9865-y Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 Impett, E. A., Gable, S., & Peplau, L. A. (2005). Giving up and giving in: The costs and benefits of daily sacrifice in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality a nd Social Psychology, 89, 327-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.327 Kashdan, T. B., & Steger, M. F. (2007). Curiosity and pathways to well-being and meaning in life: Traits, states, and everyday behav- iours. Motivation and Emotion, 31, 159-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11031-007-9068-7 Kim, Y., Carver, C. S., Deci, E. L., & Kasser, T. (2008).Adult attach- ment and psychological well-being in cancer caregivers. The media- tional role of spouses’ motives for caregiving. Health Psychology, 27, 144-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S144 Kogan, A., Impett, E. A., Oveis, C., Hui, B., Gordon, A., & Keltner, D. (2010). When giving feels good: The intrinsic benefits of sacrifice in romantic relationships for the communally motivated. Psychological Science, 21, 1918-1924. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797610388815 Kunce, L. J., & Shaver, P. R. (1994). An attachment-theoretical ap- proach to caregiving in romantic relationships. In K. Bartholomew, & D. Perlman (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships (Vol. 5, pp. 205-237). London: Kingsley. Magai, C., Hunziker, J., Mesias, W., & Culver, L. C. (2000). Adult attachment styles and emotional biases. International Journal of Be- havioural developme nt, 24, 301-309. Marris, P. (1996). Attachment in private and public life. New York: Routledge. Maslow, A. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York: Viking. Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2005). Mental representations of attachment security: Theoretical foundation for a positive social Open Access 1044  A. REIZER ET AL. psychology. In M. W. Baldwin (Ed.), Interpersonal cognition (pp. 233-266). New York: Guilford Press. Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press . Peterson, C., Park , N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full versus the empty life. Jour- nal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z Reker, G. T. (2005). Meaning in life of young, middle-aged, and older adults: Factorial validity, age, and gender invariance of the Personal Meaning Index (PMI). Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 71-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.03.010 Reker, G. T., Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1987). Meaning and purpose in life and well-being: A life span perspective. Journal of Gerontology, 42, 44-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/42.1.44 Ronen, S., & Mikulincer, M. (2009). Attachment orientations and job burnout: The mediating roles of team cohesion and organizational fairness. Journal of Social a nd Personal Relationships, 26, 549-567. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407509347930 Schnell, T. (2009). The Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Ques- tionnaire (SoMe): Relations to demographics and well-being. Jour- nal of Positive Psychology, 4, 483-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271074 Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfilment. New York: Free Press. Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2002). Attachment-related psy- cho- dynamics. Att achment and Human Development, 4, 133-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616730210154171 Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2012). An attachment perspective on coping with existential concerns. In P. R. Shaver & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), Meaning, mortality, and choice: The social psychology of ex- istential concerns (pp. 291-307). Washington DC: American Psy- chological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/13748-016 Shaver, P. R., Mikulincer, M., & Shemesh-Iron, M. (2009). A behav- ioural systems perspective on prosocial behaviour. In M. Mikulin- cer, & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behav- iour: The better angels of our nature (pp. 73-92). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Steger, M. F. (2009). Meaning in life. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed., pp. 679-687). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Steger, M. F. (2012). Experiencing meaning in life: Optimal function- ing at the nexus of well being, psychopathology and spirituality. In P. T. P. Wong, & P. S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning (2nd ed., pp. 165-184). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for mean- ing in life. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 53, 30-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., & Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76, 199-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x Stewart, L. (2011). Weaving the fabric of attachment. International Journal of Integrative P s yc h ot he ra p y, 2, 1-9. Stroope, S., Draper, S., & Whitehead, A. L. (2013). Images of a loving God and sense of meaning in life. Social Indicators Research, 111, 25-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9982-7 Open Access 1045

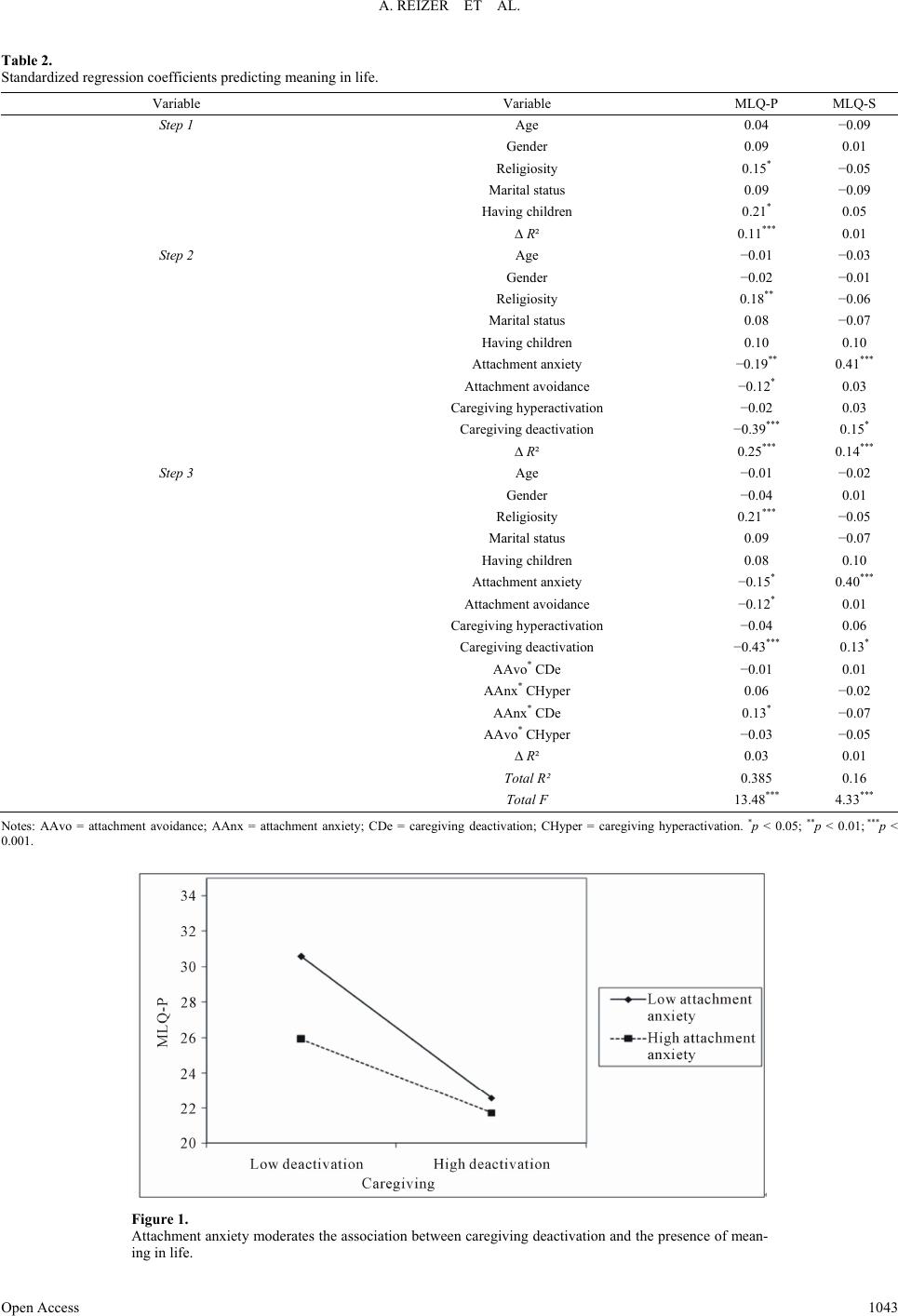

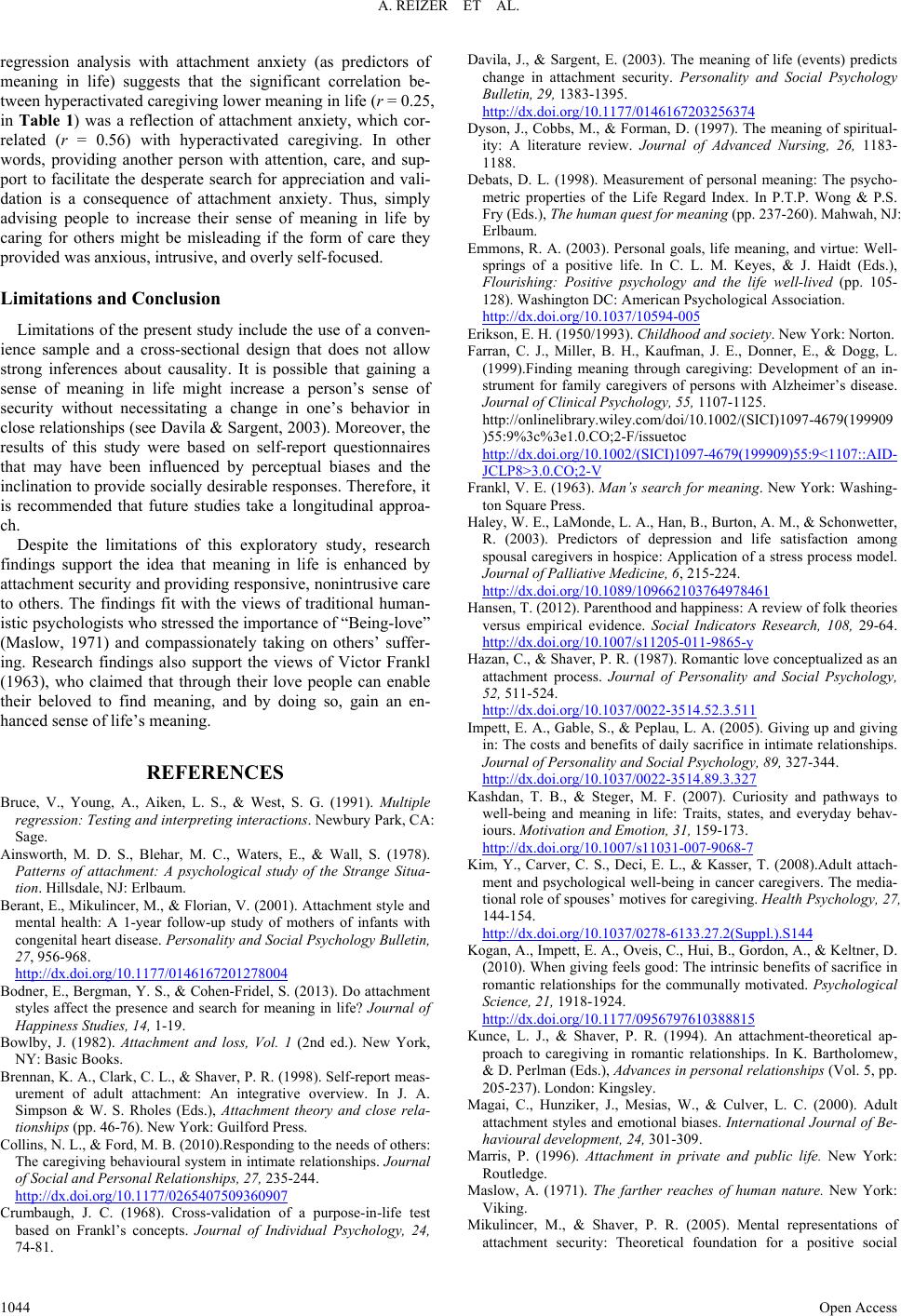

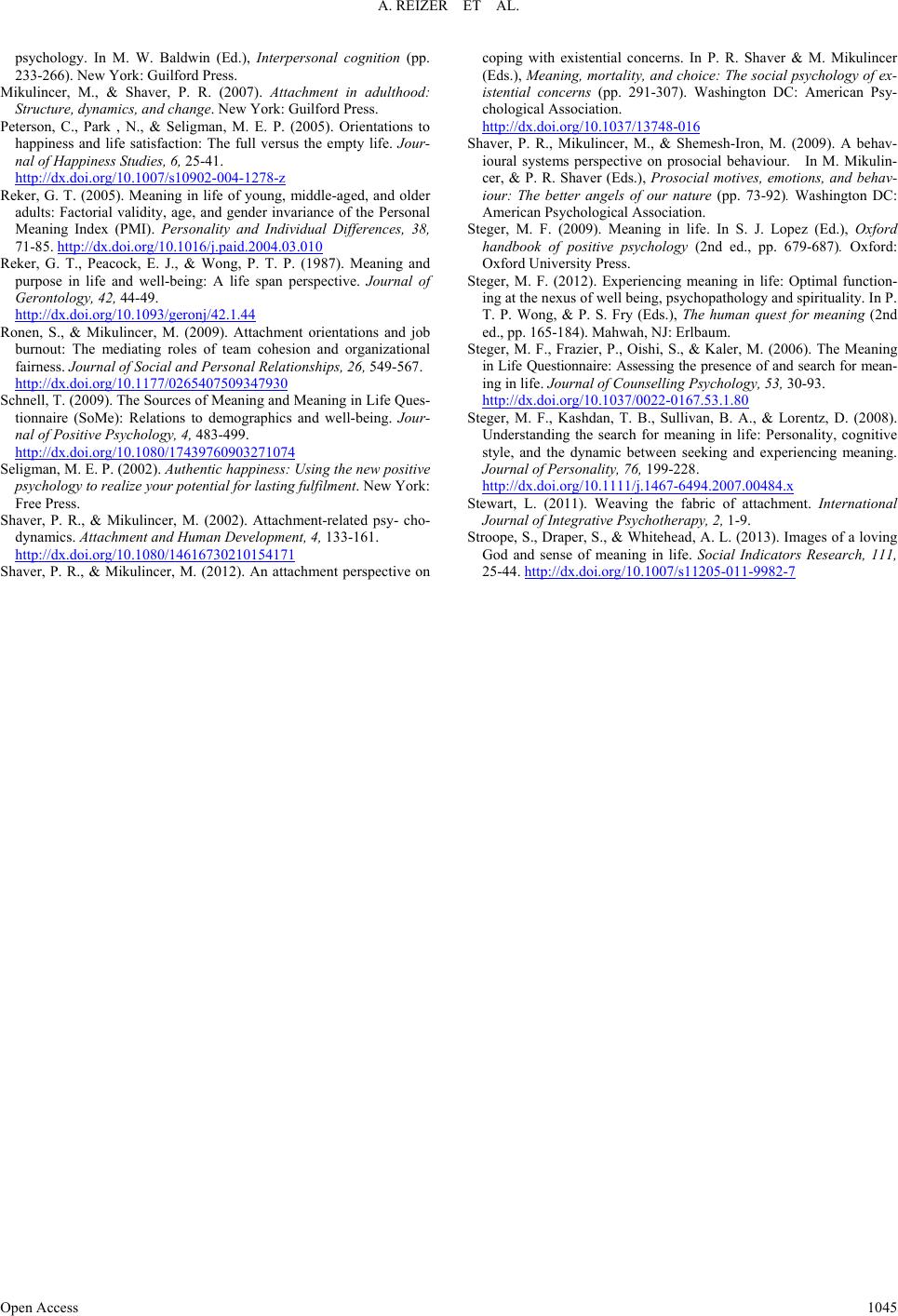

|