Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.12, 1030-1038 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.412150 Open Access 1030 The Beliefs and Attitudes about Deaf Education (BADE) Scale: A Tool for Assessing the Dispositions of Parents and Educators* M. Diane Clark1#, Sharon Baker2, Song Hoa Choi1, Thomas E. Allen1 1Gallaudet University, Washington DC, USA 2Mary K. Chapman Center, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, USA Email: #Diane.Clark@gallaudet.edu, bakers@utulsa.edu, songpineflower@gmail.com, thomas.allen@gallaudet.edu Received September 12th, 2013; revised October 8th, 2103; accepted November 6th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 M. Diane Clark et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property M. Diane Clark et al. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. This paper reports on the development of the Beliefs and Attitudes about Deaf Education (BADE) scale and presents psychometric information derived from the administration of the scale to a national sample of parents, teachers, and program administrators during Wave 1 data collection of the Early Educational Longitudinal Study (EELS). Initially the scale had 47 items; however, 26 items were eliminated during analysis because they were found to be either redundant or not contributing to the most significant under- lying latent attitudinal factors. We examined the content of the items loading highly on the factors in this final analysis to determine appropriate subscale labels for the factors. These are as follows: 1) Literacy through Hearing Technologies and/or Visual Support for Speech Comprehension; 2) Visual Language and Bilingualism; 3) Listening and Spoken Language; and 4) Difficulties Associated with Hearing Parents Learning ASL. The BADE scale will be helpful to families with deaf children and the professionals working with them as they explore the different communication options and their own personal beliefs and attitudes toward deaf education. Keywords: Deaf; Educational Attitudes; American Sign Language; Educational Choice; Literacy Introduction Decisions about how best to educate a deaf child are inextri- cably tied to the beliefs that decision-makers (parents and teachers primarily) hold about language, culture, innate capaci- ties, pedagogy, normalcy, and diversity. Throughout history, fundamental questions about the nature of humankind and the nature of human knowledge (and the important role of language in the generation of knowledge) have led philosophers to di- verge greatly in their understandings of many domains within the realm of human experience, including ethics, religion, epis- temology, politics, the nature of reality, the role of the individ- ual in society, and so forth. In turn, these have given rise to the emergence of a broad set of diverse approaches to education. Two philosophies, unique to deaf education, have existed regarding the education of deaf peoples for many centuries and can be traced back to early philosophers such as Aristotle, who wrote that one could not have intelligence without speech. In- deed, without speech, you were considered a barbarian and could not speak to God. Plato believed that language was the pathway to truth, but believed that Greek was the only true language that would lead you to true knowledge. An opposing philosophy, not articulated until the Italian Renaissance in the 15th and 16th centuries in the writings of Rodolphus Agricola and Gerolamo Cardano, argued that deaf individuals could be taught to read and write (and thus acquire knowledge). This broader view was later expanded in the philosophical views of French philosophers of the 18th century, such as Rosseau, on the role of education and the nature of an individual’s relation- ship to society. Rosseau warned of the potential damaging ef- fects of imposing societal norms on Man’s innate goodness (Doyle & Smith, 2007). The cultural perspective espoused by the 18th century French philosophers supports the use of natural sign languages (Ladd, 2002) and a Deaf epistemology (Hauser, O’Hearn, McKee, & Steider, 2010; Holcomb, 2010). This philosophy sees deaf indi- viduals as visual learners who bring knowledge to bear about the most effective practices for deaf education, tending to focus on ASL/English Bilingual educational curricula (Nover, An- drews, Baker, Everhart, & Bradford, 2002; Simms & Thumann, 2007), historically rooted in the manual philosophy which dates back to the 1700s in France. Over the years, the power and influence of the two opposing philosophies, oralism and manualism, have been compared to a pendulum with the two philosophies on either side of the pivot and signed systems or total communication existing at the point *Copies of the BADE Scale and its scoring manual can be downloaded at vl2.gallaudet.edu/Publications and Products/ASL Assessment Toolkit. #Corresponding author.  M. D. CLARK ET AL. of equilibrium. The higher the pendulum arcs and the stronger the force behind it, the more radical the beliefs and the more pronounced the eventual downswing to the opposing philoso- phy, spurring advocates on both sides to defend their beliefs and challenge opposing sides. Even when deaf education was in its infancy, there were controversies among the most prominent leaders who were steadfast in their advocacy for their particular system of beliefs. For example, in the 17th century Samuel Heinicke, a German teacher of the deaf and promoter of the oral method and the Abbe de l’Epée, a French teacher of the deaf and promoter of the manual method advocated for diametrically opposing methods. Although the controversy regarding the best communication method to teach language to deaf students be- gan much earlier, the disagreements between these two promi- nent figures escalated the controversy. It began through a series of letters, each man trying to convince the other of the fallacy of his approach and reached a pinnacle in 1783, when the Academy of Zurich was asked to hold an impartial tribunal to review the two opposing philosophies and to determine which was superior (Easterbrooks & Baker, 2002). The Academy, however, did not hear from both sides, as Heinicke was not willing to divulge the details of his approach (Marvelli, 1973). The Academy’s decision was based on the evidence presented; the judgment was made that neither method was natural, but the manual method was considered better (Scouten, Warren, Burns, Ray, Basile, Avery, & Menkis, 1984). The controversy continued a century later in the United States between two hearing sons of deaf mothers: Alexander Graham Bell, a wealthy and politically powerful ally of the oral method and Edward Miner Gallaudet who supported the use of manual signs. Both men feuded over the two philosophies through published papers and public lectures. Bell felt passion- ately that the system of education of the deaf was severely flawed and stated that manual signs perpetuated isolation of deaf people from hearing society. Moreover, Bell believed that deaf schools encouraged intermarriage among deaf people, which potentially could lead to a “deaf race”. To improve the educational system in the United States, Bell made three rec- ommendations: eliminate educational segregation in institutions, eliminate the use of sign language, and eliminate deaf teachers. On the surface Bell and Gallaudet appeared to be as diamet- rically opposed as did del’Epée and Heinicke; however, while neither de l’Epée nor Heinicke would falter from his beliefs, Gallaudet began to explore a middle ground approach. Eventu- ally he agreed that the oral method might be useful for some students (Easterbrooks & Baker, 2002). The approach Gallau- det conceptualized used ASL as the language of instruction, emphasized English through reading and writing, and provided speech lessons to those who could benefit. He called his ap- proach the Combined Method. Among his contemporaries, his approach was controversial, as they perceived the addition of speech to the curriculum as a threat. In 1886, Gallaudet con- vened a conference, focusing on developing a unifying com- munication philosophy that maintained manual signs, but added articulation and lipreading to the curriculum. He persuaded those in attendance to adopt a resolution calling for all schools for the deaf to embrace a balanced, combined approach—a forerunner of today’s ASL/English bilingual philosophy. Al- though Gallaudet’s advocacy for a combined approach gained momentum at the 1886 conference, by 1888 his efforts were thwarted by the International Congress on Education of the Deaf (ICED) held in Milan, Italy (Lane, 1989). The Congress passed a resolution claiming the superiority of the oral method in the education of the deaf. The resolution remained on the record for 122 years until the 2010 ICED conference in Van- couver, BC during which a vote occurred to rescind it. Deaf education today remains a polarized field. The legacy of controversy continues and despite efforts to blend commu- nication techniques in various combinations, the issues that were debated in the 18th and 19th centuries, continue today. The controversy impacts educational outcomes for deaf students, who on average perform well below their hearing, same-age peers (Allen, 1986; Conrad, 1979; Marschark & Harris, 1996; Musselman, 2000). Some suggest that a cultural model with its emphasis on visual language will improve educational out- comes for deaf children (Holcomb, 2010; Simms & Thumann, 2007), and there is evidence to show that deaf individuals with early ASL backgrounds tend to be academically successful (Allen & Morere, 2012; Freel, Clark, Anderson, Gilbert, Musyoka, & Hauser, 2011; Morford, Wilkinson, Villwock, Piñar, & Kroll, 2011; Padden, 1980). The decision of which educational philosophy to follow has potentially long-lasting positive or negative outcomes for deaf children. So what are the attitudes of parents, teachers, and school ad- ministrators regarding these two philosophies, and what impact do these beliefs have on the educational choices made (and the successes or failures experienced) for deaf children? Up to now, research has not systematically investigated the attitudes of parents, teachers, and school administrators about their educa- tional beliefs and attitudes. The lack of a reliable, valid measure of these beliefs is an impediment for studying their nature and prevalence, as well as their impact on education. As part of its Early Education Longitudinal Study (EELS), the NSF-funded Science of Learning Center on Visual Language and Visual Learning (VL2), undertook the design of a tool to remedy this lack. The result of this effort was the development of the Beliefs and Attitudes about Deaf Education (BADE) scale. This paper reports on the development of the BADE scale and presents psychometric information derived from the administration of the scale to a national sample of parents, teachers, and program administrators during Wave 1 of data collection of EELS. Method Scale Development To develop the BADE scale, the researchers developed 47 items reflecting the range of views about Deaf education based on long standing issues found in deaf education and reflected in the introduction. These issues focus on communication choices, the language of instruction, and the use of technology. Addi- tionally, there are the two views or models of deaf individuals also discussed in the introduction. In summary, the first model is that deaf people represent a linguistic minority and reflect a visual culture, which is referred to as a cultural model of deaf people while the model adopted by most hearing people, who do not interact with deaf people, is the medical model, where deaf people are viewed as needing to be fixed. Items were de- veloped to reflect these various issues. A concerted attempt was made to maintain neutrality with respect to opposing philoso- phies and to include roughly equal numbers of statements rep- resenting different points of view. A 5-point Likert scale repre- senting levels of agreement (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree) was attached to each scale item. The respon- dents’ task was to indicate their level of agreement with each Open Access 1031  M. D. CLARK ET AL. statement using the 5-point scale. The statements covered a range of topics, including: • Communication choices, such as ASL (e.g., Deaf and hard of hearing children can learn ASL), Cued Speech (e.g., Deaf and hard of hearing children can learn English if it is made accessible through a combination of residual hearing, speechreading, and Cued Speech as infants), spoken lan- guage (e.g., Because sign language hinders the develop- ment of listening and talking, young deaf or heard of hear- ing children should be allowed to develop spoken language initially without the influence of signs), and signed systems (e.g., Talking and signing at the same time provides chil- dren access to both a visual and an auditory language); • Technology (e.g., New technologies (e.g., cochlear implants) are effective in producing normal-like hearing ability in deaf children); • Medical interventions (e.g., Efforts initially should focus on medical interventions in order to try to reduce the negative effects of hearing loss); and • Culture and bilingualism(e.g., Being a member of a Deaf community with a unique culture and language enriches one’s life). The 47 items are presented as an Appendix to this paper. The Early Education Longitudinal Study and Study Participants The EELS sample was recruited from schools that had agreed to become VL2 School Partners. These schools were invited to participate in a three-year longitudinal study to inves- tigate, 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old deaf children’s cognitive, language, and literacy development during the critical period when they were transitioning into school. In turn, the schools that joined the project, recruited families to participate. Modeled after the US Department of Education’s Pre-Elementary Educational Longitudinal Study (PEELS) conducted by the National Center for Special Education Research (Markowitz et al, 2006), this longitudinal study included: 1) a comprehensive battery of di- rect assessments of cognitive skills, language skills, and emerging literacy skills; 2) a set of indirect assessments of so- cial, communication, academic, and language development embedded in Parent and Teacher surveys targeted at providing ratings on project participants; 3) Parent Surveys, including (in addition to the indirect assessments and the BADE scale) ques- tions on family background, literacy and language practices in the home, cochlear implant use and experience, and interactions between school and home; 4) Teacher Surveys, including (in addition to the indirect assessments and the BADE scale) ques- tions about classroom practices; and 5) Program Administrator Surveys, including (in addition to the BADE tool), questions about school policies. All participants, including the children who were given a small toy worth less than $5.00, were com- pensated for completing the surveys. The types of schools included in the survey were public and private pre-schools, as well as early childhood programs. Schools were located in 23 states in various sized communities; 13% of the schools were in very large cities, 23% in large cities, 8% in medium-sized cities, 15% in suburbs, 17% in small cities or towns of fewer than 50,000 people, 21% in rural areas, and 2% were on an Indian reservation. The schools had relatively high levels of federal funding with 73% of schools receiving these funds. The programs participating in this longitudinal project varied, including both mainstream programs and deaf schools as re- ported by the school administrators. Many of the programs were centered based preschool programs that served primarily hearing children; 25% as reported by administrators, which served 40% of the children. Other programs were center based childcare programs that primarily served hearing children; 3% as reported by administrators serving 4% of the children. Center based preschool programs that primarily serve deaf or hard of hearing children were reported by 43% of the administrators and these programs served 70% of the children while 3% were child care programs for deaf and hard of hearing children (4% of the children.) An addition 13% were reported as home based programs for deaf and hard of hearing children, which served 21% of the children. Finally administrators reported that 14% of the programs were clinics that provided occupational and/or speech and language therapy, serving 23% of the children. Of the 251 Wave 1 participants, 159 children had parents who completed the parent survey. Of these children, 100 were from hearing families, and 59 had a least one deaf parent in the home. Languages used in the home included English (42%), Spanish (5%), ASL (43%), and signed English (10%). Please note that parents were able to report more than one home lan- guage. Of all of the children in the survey (n = 199), 57 had cochlear implants while 142 did not have a cochlear implant. Completed surveys from 62 teachers and 48 school adminis- trators were received; these surveys were linked to a total of 191 children, owing to the fact that teachers and administrators came from classrooms or schools with more than one deaf stu- dent participant. For the current analysis, designed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the BADE scale, item response data from the teacher, parent, and administrators surveys were merged into a single data set containing 269 records. Analytic Plan Our strategy for analyzing and refining the BADE scale in- cluded several steps. First, we analyzed the raw item responses with an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to determine the underlying latent structure. The EFA was computed using IBM SPSS, version 19.0. A principal component analysis was used to obtain the structure. A rotated component matrix was ob- tained by using a varimax rotation to maximize the distinctive- ness of the factors and facilitate interpretation (Field, 2009). We evaluated the Scree plot, and selected factors with the highest Eigenvalues (greater than .4). We examined the content of items with the highest loadings on these factors and assigned labels to the resulting subscales. We subsequently conducted a reliability analysis of the resulting scales, and eliminated items demonstrating the lowest item to scale correlations. Finally, we re-ran the Factor Analysis with the reduced item set to confirm the stability of the derived scales. Results Using the scree plot, it was determined that the elbow oc- curred at 4 factors. Subsequent analysis was based only on items loading significantly on these four factors. To create sub- scales that would have utility in determining prevalent attitudes of future respondents, we chose to retain only those items load- ing greater than .5 on each of the top four factors, resulting in Open Access 1032  M. D. CLARK ET AL. highly distinct subscales. Using this criterion, 26 of the original 47 items were retained. Reliability analysis using Cronbach’s Alpha on each of the four subscales resulted in highly reliable scales: (Factor 1 α = .91, Factor 2 α = .89, Factor 3 α = .80 and Factor 4 α = .85). Given that we had eliminated 21 items as being either re- dundant or as not contributing to the most significant underly- ing latent attitudinal factors, and that the reliability analysis utilized unit scaling (raw item responses, unweighted by the resulting factor loadings), we re-ran the factor analysis to assess whether the relative orthogonality of the factors would be maintained with the reduced item set. As expected the strength of the four-factor structure was increased after deleting unreli- able items, resulting in a set of four factors with item loadings highly similar to the first analysis and a structure that explained 61.3% of the total item variance. We examined the content of the items loading highly on the factors in this final analysis to determine appropriate subscale labels for the factors. These are as follows: Literacy through Hearing Technologies and/or Visual Support for Speech Comprehension (eigenvalue = 5.81, explaining 22.3% of the total variance); Visual Language and Bilingualism (eigenvalue = 5.09, explaining 19.6% of the total variance); Listening and Spoken Language (eigenvalue = 2.95, explaining 11.3% of the total variance); and Difficulties Associ- ated with Hearing Parents Learning ASL (eigenvalue = 2.08, explaining 8% of the total variance). The overall structural model showing these four factors and the loadings of their as- sociated items is presented in Figure 1. Finally, we developed simple subscale computational rules for users of the BADE instrument that entailed adding together the Likert ratings for all the items within each of the subscales and dividing by the number of items in the subscale. This yielded a set of four scores between 1 and 5 (the same as the Likert ratings themselves) that represented the average rating of respondents for items within each subscale. Subscale scores below three demonstrate a level of disagreement with the state- ments within the scale. Subscale scores above three indicate a level of agreement with the statements within the scale. Scores clo- se to three indicate the lack of an opinion one way or another. A follow-up, post-hoc analysis was performed on the newly developed subscales. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the BADE subscales broken down by the con- stituent caregiver groups (Parents, Teachers, and Administra- tors). In this longitudinal sample, there was strong agreement among all groups to items representing the Visual Language and Bilingualism subscale. Parents expressed mean levels of agreement to the Literacy through Hearing Technologies and/or Visual Support for Speech Comprehension scale that exceeded 3 points, whereas Teachers and Administrators were more likely to disagree with statements oriented to this phi- losophy. Respondents from all groups tended to disagree with statements indicating that learning ASL with English might pose a threat to later language development (Listening and Spoken Language), though, again, parents showed higher levels of agreement than the other two groups. All three groups showed quite low levels of agreement with statements suggest- ing that hearing parents would have difficulty learning ASL (Difficulties Associated with Hearing Parents Learning ASL.) While the factor analysis yielded orthogonal factors and helped sort statements into factors exhibiting the highest levels of within-factor communality and between factor uniqueness, the unit scaling proposed for easily computing interpretable subscale scores, undermines the orthogonality by using the unweighted item ratings directly in the computation of the scores. Table 2 presents the correlation matrix of the derived scores. It is clear that the scaling strategy proposed results in considerable co-linearity among the derived scores. However, the pattern of correlations among the subscale scores is quite interesting, and also quite predicable from the two opposing educational philosophies described at the beginning of this paper. The Literacy through Hearing Technologies and/or Vis- ual Support for Speech Comprehension subscale correlated positively with both the Listening and Spoken Language sub- scale and the Difficulties Associated with Hearing Parents Learning ASL subscale, reinforcing the idea that a strong orien- tation toward literacy through hearing technologies, speech reading, and/or cued speech imply negative attitudes about bilingualism and low expectations about parents’ abilities to acquire sufficient sign skill to employ a rich visual language in the early childhood experiences of preschool deaf children. At the same time, the Visual Language and Bilingualism subscale demonstrated significant and moderately high negative correla- tions with all of the other subscales. Again, this finding rein- forces the presence of a strong dichotomy of attitudes in the population (and speaks to the validity of the BADE scale for studying attitudinal differences among participant subgroups). Finally, the correlation between the perceived Difficulties Asso- ciated with Hearing Parents Learning ASL subscale and the Listening and Spoken Language was a substantial .61 and highly significant. Those who perceived ASL as a threat to later language development tended also to underrate a parent’s abil- ity to master ASL. In effect, these two scales present an attitude of monolingualism. Discussion The BADE scale includes 26 items and four subscales; Lit- eracy through Hearing Technologies, Visual Language and Bilingualism, Listening and Spoken Language, and Difficulties for Hearing Parents to Learn ASL. The BADE scale was de- veloped to allow parents, early interventionists, and teachers to better understand their own attitudes about best practices for young deaf learners. As such, if permits users to determine their current beliefs. The four subscales can stimulate dialogues about other possibilities that parents may be unaware of during the initial moments of learning that they have a child who has just “failed” their first test (Early Intervention: The Missing Link; http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5ZqKMgXciU). The scale helps parents to understand that there are multiple ways to view a child’s hearing status, that there are many communica- tion opportunities for parents, and that they are not mutually exclusive. The scale can help parents manage their shock and possible fear that they child is disabled and will be unable to function fully in a “hearing world”. As such, the BADE scale was developed to reduce the stress and anxiety associated with having a young deaf learner. The results of the screening tool may be helpful in examining conflicting belief systems and to help frame discussion points among those involved in deaf children’s educational programs. Historically, hearing parents tend to choose a Literacy through Hearing Technologies and/or Visual Support for Speech Comprehension approac for their deaf children, and h Open Access 1033  M. D. CLARK ET AL. Open Access 1034  M. D. CLARK ET AL. Figure 1. Path diagram of the four factors and their item loadings. Table 1. Means and standard deviations for bade subscales constituent caregiver groups. Parents (N = 139) Teachers (N = 45) Administrators (N = 41) Literacy through Hearing Technologies 3.17(.83) 2.61 (.90) 2.87 (.74) Visual Language & Bilingualism 4.01 (.64) 4.12 (.61) 3.98 (.73) Listening and Spoken Language 2.22 (.89) 1.53 (.63) 1.73 (.81) Difficulties for H earing Parents to Learn ASL 1.71 (.90) 1.37 (.62) 1.71 (.91) Based on a Likert Scale, where 1 = Strongly Disagree and 5 = Strongly Agree. Table 2. Correlation Matrix: Beliefs and Attitudes about Deaf Education Sub- scales. V-B L-S DHPLASL L-H-T −.54** .50** .33** V-B −.50** −.43** L-S .61** (**Correlation is significant at the .01 level, 2-tailed; L-H-T = Literacy through Hearing Technologies and/or Visual Support for Speech Comprehension Subscale; V-B = Visual Language & Bilingualism Subscale; L-S = Listening and Spoken Language; DHPLASL = Difficulties for Hearing Parents to Learn ASL Subscale). this choice has occurred despite efforts by early intervention providers to present all communication options in a neutral, non-biased way. Early intervention, however, is typically a “medical” service provided by medical professionals; therefore, neutrality may be difficult to achieve and may be an unrealistic goal given the backgrounds of service providers. Regardless of these factors, there are most likely other underlying reasons influencing hearing parents during this decision-making process that involve their beliefs and attitudes. Hearing parents naturally want their children to be a part of their own cultural heritage and linguistic milieu; varying from this norm would be challenging as has been explained recently in the bestselling book: Far From the Tree: Parents, Children and Their Search for Identity by Solomon (2012). According to Solomon, when parents produce a child they hope that their own lives will continue in their children. Parents of children who fall Far from the Tree are unprepared when their children are born with or acquire unfamiliar needs. Further, although Open Access 1035  M. D. CLARK ET AL. some parents take pride in how different their children are from them, most are prone to endless sadness at this difference. As a result, Solomon states that “parenthood abruptly catapults par- ents’ in a permanent relationship with a stranger and the more alien the stranger, the more negative the attitudes” (pg.16). Hearing parents’ response initially to the identification of their child’s hearing loss and the decisions they make regarding communication philosophies and educational placement are most likely a result of wanting to give their deaf children op- portunities to be Nearer to the Tree or to be aligned with their own culture and value system. Although professionals providing information and counsel- ing to families strive to maintain neutrality, they bring their own set of beliefs and attitudes to this process and likely influ- ence families’ decisions. Exploring one’s own beliefs and atti- tudes including from where they originated (e.g., from family members or personal experiences, from university preparation programs) and how they have changed or crystallized maybe a useful exercise. Further, exploring one’s beliefs and attitudes toward children whose linguistic needs fall far from the tree may bring new insights. When service providers, teachers, and administrators beliefs and attitudes are in contrast with the family’s, the BADE tool may be useful to analyze where they diverge and may serve as a springboard for further discussion of vertical identities and horizontal identities. Vertical identities, as Solomon (2012) explains, tend to be those which could be described as falling within the family’s accepted cultural norms and expectations, many of which have been passed down from generation to gen- eration. Language, according to Solomon, is typically a vertical identity because it is normally transmitted from parent to child, and parents tend to want their children to communicate using the shared language of the home. Vertical identities also include attributes and values that are passed down (e.g., ethnicity, hair color, DNA, cultural expectations). Horizontal identities, which tend to be foreign to parents, are typically not found in the fam- ilies’ heritage or culture and therefore, fall outside the vertical- ity of the familiar (e.g., prenatal influences, values and prefer- ences that the child does not share with the family, recessive genes). While vertical identities emerge from families, hori- zontal identities are usually acquired from a peer group. In the case of deaf children who sign and have hearing parents, in- stead of language being vertical and transmitted from parent to child, it is most often horizontal where outsiders and peers be- come the language models while parents are acquiring commu- nication skills. Using the BADE scale can open a dialogue between physi- cians, audiologists, early interventionists, educators, and par- ents. It can provide an opportunity to discuss a variety of com- munication options, including the pros and cons related to each choice. In this way, parents can explore multiple options at a time when many of them are grieving the loss of an “ideal” child who is like them. For most hearing parents, the first deaf person they meet is their own child (Benedict, 2013) who has just “failed” their first test—they cannot hear. This emotional situation can be framed as a dialogue about possibilities that are researched based. Clearly, early interventionists and teachers need new tools to assist parents in choosing early communica- tion approaches that take full advantage a child's intact sensory potential. Further, early communication approaches must be carefully monitored to ensure that children are acquiring lan- guage on a normal trajectory; otherwise the result of lack of early access to a fully-functioning language system may lead to severe academic delays. New emerging research is revealing that ASL/English bilingualism (Mayberry & Locke, 2003; Pé- nicaud et al., 2013) leads to successful cognitive and linguistic development for a child who is deaf or hard of hearing. This ASL/English bilingualism maybe bimodal, where the child learns both speech and sign language (Nussbaum, Scott, & Simms, 2012) at the same time to take advantage of the epige- netic benefits of accessible early language (Pénicaud et al., 2013). Depending on family wishes and the success of hearing restoration, these children may elect to drop sign language if their spoken language development provides them academic language and effective progress in their education. If the child is not able to depend solely on spoken language for academic success, they are optimally positioned to take advantage of both sign and spoken languages given the benefits of early ASL/ English bilingualism. Limitations and future research. This longitudinal sample is predominantly from center-based programs that serve deaf and hard of hearing children. As such, many of the programs had a strong bilingual philosophy. In addition 68% of the par- ents reporting using ASL at home, even if they themselves were not native signers. Given these characteristics of the sample, future research could administer the BADE to parents of chil- dren who are more English-only in their educational philosophy. This data could then be used in a confirmatory factor analysis to determine whether or not the items load on the same factors when parents have selected more listening and spoken language educational programs. Conclusion. The BADE scale provides a mechanism to frame future opportunities for deaf and hard of hearing children who most often are born to hearing families. This scale can help parents, early interventionists, and teachers analyze their own attitudes and beliefs in order to better meet the needs of young deaf learners. If parents and early interventionist/teachers atti- tudes differ, the BADE scale can provide a point of reference for discussion and dialogue about what each expects to occur for the child. Moreover, the BADE scale can be used to connect to recent efforts, which provide more information about the benefits of early sign language (http://vl2.gallaudet.edu, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5ZqKMgXciU, and http://www.jaclynvincent.com). This information can help par- ents navigate possibilities for language choice and educational placements that reflect the full range of possibilities. As the deaf baby is often the first deaf person most hearing parents meet, they tend to be unaware of deaf culture and the benefits of visual language. The BADE scale can provide an opening to choices that are often not reflected by those in the medical pro- fession. REFERENCES Allen, T. (1986). Patterns of academic achievement among hearing impaired students: 1974 and 1983. In A. Schildroth, & M. Karchmer (Eds.), Deaf children in America (pp. 161-206). San Diego, CA: Col- lege Hill Press. Allen, T., & Morere, D. A. (2012). Underlying neurocognitive and achievement factors and their relationship to student background characteristics. In D. A. Morere, & T. Allen (Eds.), Assessing liter- acy in deaf individuals: Neurocognitive measurement and predictors (pp. 231-261). New York: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5269-0_13 Benedict, B. (2013). How early intervention can make a difference: Open Access 1036  M. D. CLARK ET AL. Open Access 1037 Research and trends. The VL2 Educational Neuroscience Presenta- tion Series, 2, Washington DC: Gallaudet University. Conrad, R. (1979). The deaf school child. London: Harper and Row. Doyle, M. E., & Smith, M. K. (2007). Jean-Jacques Rousseau on nature, wholeness and education. http://www.infed.org/thinkers/et-rous.htm Easterbrooks, S. R., & Baker, S. K. (2002). Language learning in chil- dren who are deaf and hard of hearing: Multiple pathways. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. Freel, B. L., Clark, M. D., Anderson, M. L., Gilbert, G. L., Musyoka, M. M., & Hauser, P. C. (2011). Deaf individuals’ bilingual abilities: Ame- rican sign language proficiency, reading skills, and family character- istics. Psychology, 2, 18-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2011.21003 Hauser, P. C., O’Hearn, A., McKee, M. G., Steider, A. M., & Thew, D. (2010). Deaf epistemology: Deafhood and deafness. American An- nals of the Deaf, 154, 486-492. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/aad.0.0120 Holcomb, T. K. (2010). Deaf epistemology: The deaf way of knowing. American Annals of the Deaf, 154, 471-478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/aad.0.0116 Ladd, P. (2002). Understanding deaf culture: In search of deafhood. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Lane, S. (1989). Determining the determiner: Aspects of teaching “the” and “a” in ESL. Washington DC: US Department of Education, Of- fice of Educational Research and Improvement. National Association for Foreign Student Affairs Conference. Markowitz, J., Carlson, E., Frey, W., Riley, J., Shimshak, A., Heinzen, H., Strohl, J., Lee, H., & Klein, S. (2006). Preschoolers’ characteris- tics, services, and results: Wave 1 overview report from the Pre- Elementary Education Longitudinal Study (PEELS). Rockville, MD: Westat. www.peels.org. Marschark, M., & Harris, M. (1996). Success and failure in learning to read: The special case of deaf children. In J. Oakhill & C. Cornoldi (Eds.), Children’s reading comprehension disabilities: Processes and intervention (pp. 279-300). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Marvelli, A. L. (1973). An historical examination and organizational analysis of the Smith College-Clarke School for the deaf graduate teacher education program. Dissertation Abstracts International, 7415029. Mayberry, R.I., & Lock, E. (2003). Age constraints on first versus second language acquisition: Evidence for linguistic plasticity and epigenesist. Brain and Language, 87, 369-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00137-8 Morford, J. P., Wilkinson, E., Villwock, A., Piñar, P., & Kroll, J. F. (2011). When deaf signers read English: Do written words activate their sign translations? Cognition, 118, 286-292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2010.11.006 Musselman, C. (2000). How do children who can’t hear learn to read an alphabetic script? A review of the literature on reading and deafness. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf E ducation, 5, 9-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/deafed/5.1.9 Nover, S., Andrews, J., Baker, S., Everhart, V., & Bradford, M. (2002). Staff development in ASL/English bilingual instruction for deaf stu- dents: Evaluation and impact study. Center for ASL/English Bilin- gual Education and Research: New Mexico School for the Deaf. Nussbaum, D. B., Scott, S., & Simms, L. E. (2012). The “why” and “how” of an asl/English bimodal bilingual program. Odyssey, 13, 14-19. Padden, C. (1980). The deaf community and the culture of deaf people. In C. Baker, & R. Pattison (Eds.) Sign language and the deaf com- munity. Silver Spring: National Association of the Deaf. Pénicaud, S., Klein, D., Zatorre, R. J., Chen, J., Witcher, P, Hyde, K., & Mayberry, R. I. (2013). Structural brain changes linked to delayed first language acquisition in congenitally deaf individuals. NeuroI- mage, 66, 42-49. Scouten, E., Warren, K., Burns, K., Ray, B., Basile, M. L., Avery, K., & Menkis, P. (1984). Dactylology: Words on your hands. New York: Rochester Technical Institute of Technology, National Technical In- stitute for the Deaf. Simms, L., & Thumann, H. (2007). In search of a new, linguistically and culturally sensitive paradigm in deaf education. American Annals of the Deaf, 152, 302-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/aad.2007.0031 Solomon, A., (2012). Far from the tree: Parents, children, and search for identity. New York: Scribner. Visual Language and Visual Learning Science of Learning Center. (2011). Advantages of early visual language (Research Brief No. 2). Washington DC: Sharon Baker.  M. D. CLARK ET AL. Appendix A. Beliefs about Deaf Education Questionnaire Items (47 Original Items) 1) Children less than six years old should receive general services for developmental delays and not be labeled with a specific disability. 2) Learning in the regular classroom through an interpreter produces higher levels of learning than a deaf education class- room with a teacher of the deaf. 3) Learning two languages would be too great a challenge for young deaf or hard of hearing children. 4) Deaf or hard of hearing children should enter hearing classrooms as soon as possible in order for them to learn grade-level information along with their hearing peers. 5) Talking and signing at the same time provides children access to both a visual and an auditory language. 6) Young deaf and hard of hearing children can learn finger- spelling as infants. 7) Deaf or hard of hearing infants and toddlers should re- ceive early intervention services primarily through training provided to their parents/guardians in natural environments. 8) Many hearing parents do not learn to sign because they have chosen another communication approach for their child. 9) It is a positive experience to have parents of deaf or hard of hearing children meet deaf adult. 10) Talking combined with Cued Speech (CS) and/or speechreading provides children visual and auditory access to language. 11) Because sign language hinders the development of lis- tening and talking, young deaf or hard of hearing children should be allowed to develop spoken language initially without the influence of signs. 12) If children have early access to spoken language through hearing without visual supports then they will development better later language skills. 13) If children use hearing aids, they will learn language through their residual hearing regardless of the level of hearing loss. 14) Using any visual supports while talking is confusing and hinders the development of auditory access to language. 15) ASL is a visual language aids, they will learn language through their residual hearing regardless of the level of hearing loss. 16) With amplification (hearing aids or a cochlear implant) and focused early intervention, deaf children will be able to attend regular classes in elementary school without needing an interpreter or transliterator. 17) New technologies (e.g., cochlear implants) are effective in producing normal-like hearing ability in deaf children. 18) Language can be learned visually; therefore, American Sign Language (ASL) is an appropriate communication ap- proach for young children. 19) Cued Speech is an appropriate communication approach for young children. 20) Families must focus on a child’s medical diagnosis and concentrate on therapeutic interventions during the first three years. 21) Hearing parents cannot learn ASL; therefore, it is much more effective to help them learn English-based signs or Cued Speech. 22) Hearing parents cannot learn ASL; therefore, the focus should be on the child’s oral language skills. 23) Parents must make choices about which communication approach to use with their young child. 24) Efforts initially should focus on medical interventions in order to try to reduce the negative effects of hearing loss. 25) If children have early access to spoken language through residual hearing and/or vision (e.g., speechreading, Cued Speech) they will development better later language skills. 26) If children have early access to sign, they will develop better later language skills. 27) Many hearing parents do not learn to sign because they are overwhelmed by other demands on their resources (e.g., other children, finances, other conditions of the child). 28) Cued Speech, because it provides an accurate visual rep- resentation of oral language, can map the brain of young deaf and hard of hearing children, thus giving them an advantage for later developing literacy. 29) All deaf or hard of hearing children should be educated in the regular classroom with hearing peers regardless of age. 30) ASL, because it is a visual language, can map the brain of young deaf and hard of hearing children thus giving them an advantage for later developing literacy. 31) Enrollment in a residential school for the deaf should occur as early as possible. 32) Academic content can be best learned through ASL. 33) Academic content can be best learned through the lan- guage in which the child will be reading so that they will have access to the same vocabulary and language skills in print and in class. 34) Parents and teachers of deaf or hard of hearing children should use a combination of all techniques in order to make sure the child is not limited by one approach. 35) Enrollment in a residential school for the deaf should only be selected when all other placements have failed (e.g., hearing preschool, regular kindergarten, public school main- streamed classrooms). 36) Deaf and hard of hearing children can learn ASL. 37) made accessible through a combination of residual hear- ing, speechreading and Cued Speech as infants. 38) Being able to read and write is more important than be- ing able to listen and speak. 39) Learning American Sign Language isolates young chil- dren from the hearing world. 40) Being a member of a Deaf community with a unique culture and language enriches one’s life. 41) A bilingual environment that includes ASL provides full access to language and communication. 42) Deaf and hard of hearing children’s behavior problems come mostly from frustration caused by lack of communication. 43) Deaf and hard of hearing children can become fluent in English (reading and writing) if given early access to language through ASL in the first year of life. 44) Special schools for the deaf provide a language-rich ed- ucational experience that cannot be replicated in a public school. 45) Deaf and hard of hearing children who do not have ac- cess to ASL when young struggle academically throughout their lives. 46) Deaf and hard of hearing children can become fluent in English (reading and writing) if given access to spoken lan- guage through hearing, speechreading, and/or Cued Speech in the first year of life. 47) Full access to language and communication is possible for deaf children without the use of ASL. Open Access 1038

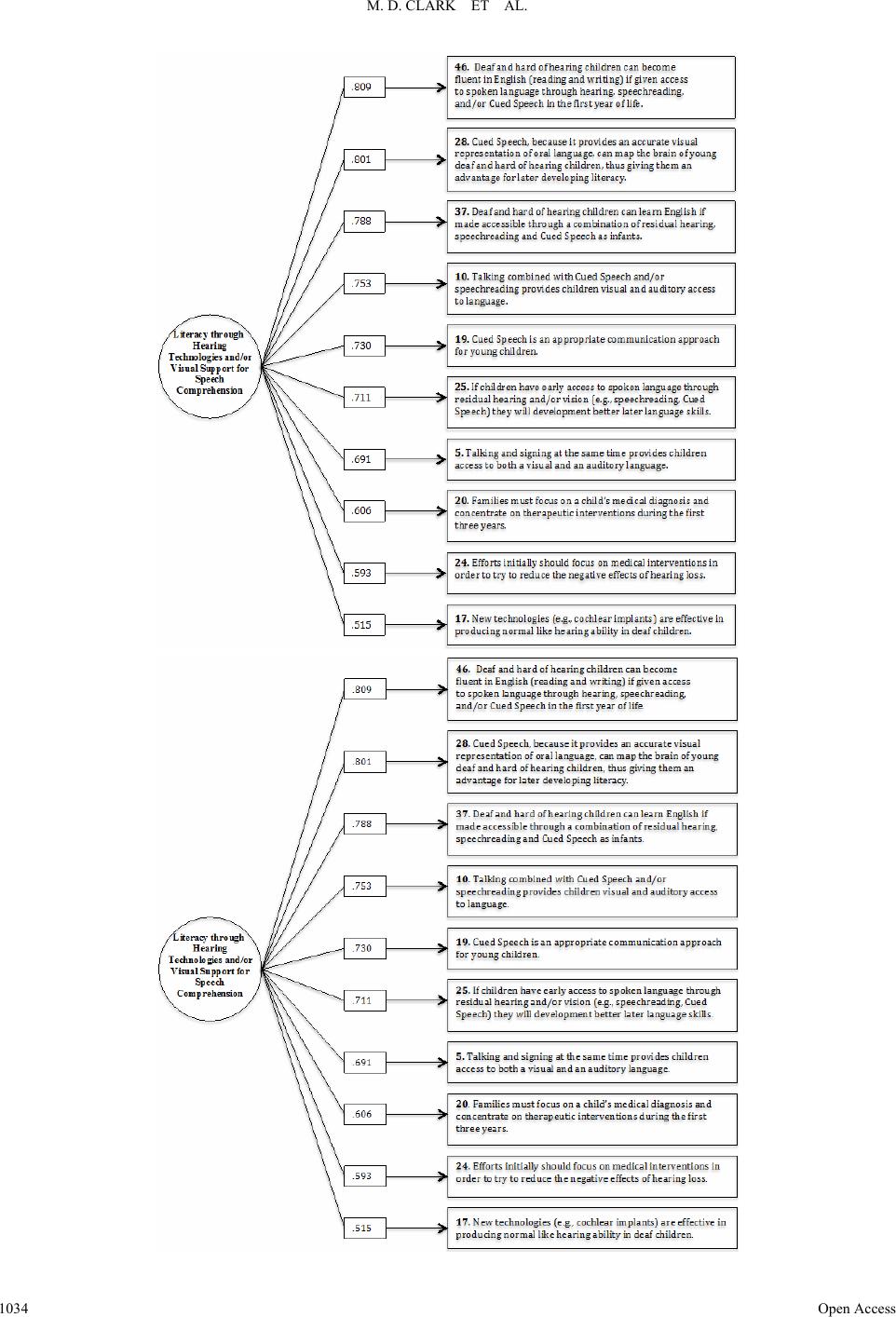

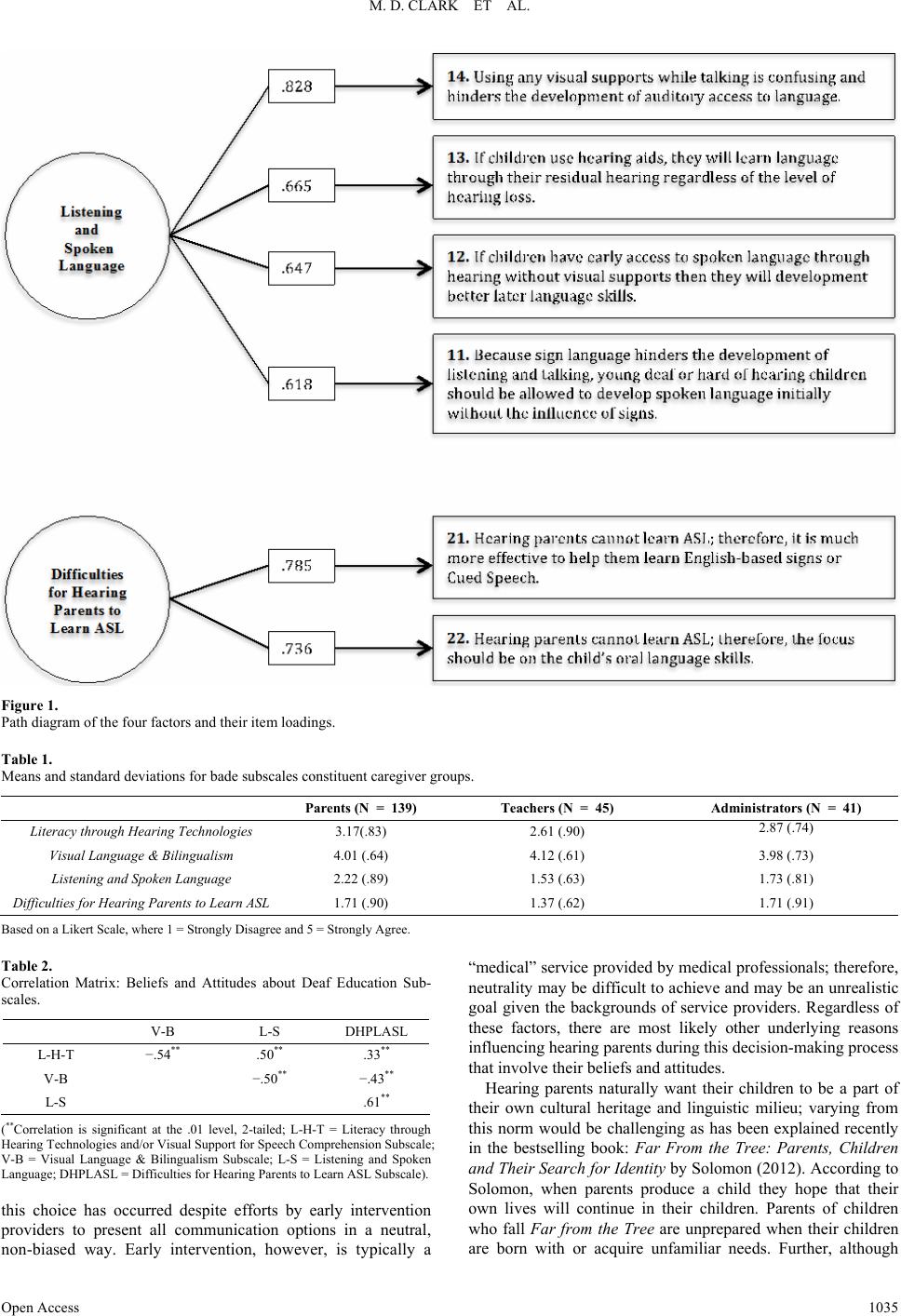

|