Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.12, 1008-1013 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.412146 Open Access 1008 Prevalence of Behavioural and Emotional Problems among Two to Five Years Old Kosovar Preschool Children—Parent’s Report Merita Shala1, Milika Dhamo2 1Faculty of Social Sciences, European University of Tirana, Tirana, Albania 2Psychology Department, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Tirana, Tirana, Albania Email: merishala@gmail.com Received October 1st, 2013; revised November 3rd, 2013; accepted November 28th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Merita Shala, Milika Dhamo. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Merita Shala, Milika Dhamo. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. Preschool age is characterized by a rapid development in all aspects of child development. During this development, the introduction of emotional and behavioral disorders can happen to any child. Preschool children have been a neglected population in the study of psychopathology. The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA), which includes the Child Behavior Checklist/1.5 - 5 (CBCL/1.5 - 5), constitutes the few available measures to assess preschoolers with an empirically derived taxonomy of preschool psychopathology. The study was based on an age- and gender-stratified sample of 755 chil- dren aged 1.5 - 5 years from five municipalities of Kosovo. The CBCL/1.5 - 5 form was voluntarily com- pleted by the parents of 426 or 56.4% boys and 329 or 43.6% girls. There were 639 or 84% mothers and 116 or 15.4 % fathers. The prevalence of total problems was estimated as 2.9%, the prevalence of exter- nalizing behavior problems was 2.5%, while the prevalence of internalizing behavior problems was 3.8%. These results are low compared to other international studies. The results revealed that there are not sig- nificant differences in mean scores among boys and girls on total problems, internalizing and externaliz- ing. Regarding the age, there are statistical differences within the decreasing of age among the three broad-bands syndromes. Such findings highlight the way in which preschool behavior problems may vary within specific cultural settings and underscore the need for in-depth research to explore the contexts. Keywords: CBCL; Preschool Children; Behavior Problems; Internalizing; Externalizing Introduction Social-emotional development captures a broad swath of spe- cific outcomes, ranging from the ability to identify and under- stand one’s own and others’ feelings, establish and sustain rela- tionships with both peers and adults, and regulate one’s behav- ior, emotions, and thoughts (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2005). In the literature, children’s behav- ioural and socio-emotional adjustment is generally indicated by the extent of their manifestation of behaviour problems (Camp- bell, 1995; Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2006). Behaviour problems have often been conceptualized along two broad spec- trums: internalizing problems which are expressed in intraper- sonal manifestation, such as anxiety, depression and with- drawal; and externalising problems which are demonstrated in interpersonal manifestation, such as hyperactivity and aggres- sion (Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000; Dearing et al., 2006). It has been reported that approximately 5% to 14% of kindergarten children in the general population exhibit mod- erate-to-severe behavioural problems (Lavigne et al., 1996; Luk et al., 1991) while Campbell (1995), states that approximately 10% - 15% of preschool children are mild to moderate behavior problems. In a comprehensive review of studies about the prevalence of psychiatric disorders, Roberts et al. (1998) re- ported prevalence rates of preschool children between 3.6% and 24% with a mean of 10.2%. The literature is more inconsistent about gender differences during the preschool period (Campbell, 1995). The literature suggests that boys and girls often manifest different health, mental health, social, and behavior problems (Baillargeon et al., 2007; Maschi et al., 2008). Some studies have shown that girls are much more likely to cope with stress using internalizing behaviors (e.g., anxiety and depression) while boys are more likely to use externalizing behaviors (e.g., anger or aggression) (Hoffman & Su 1997; Moffitt et al., 2001). Furthermore, other research has reported a significant correlation between inter- nalizing and externalizing problems (e.g. Achenbach & Res- corla, 2000; Mesman, Bongers, & Koot, 2001). Achenbach and Rescorla (2000) found a positive correlation between internal- izing and externalizing scores among a national US sample, suggesting that children tend to score similarly in both areas of problems. Another body of research has revealed gender differences in behaviour problems, especially in externalizing behaviour. For instance, it has been reported that boys tend to manifest exter- nalizing problems more than girls (Prior, Smart, Sanson, & Oberklaid, 1993). Keenan and Shaw (1997, 2003) argued that gender differences in externalizing behavior are not apparent until toddlerhood and become more pronounced in preschool.  M. SHALA, M. DHAMO Although gender differences in externalizing problems are well documented (see Maccoby, 1998), relatively little is known about these behaviors in girls (Hinshaw, 2002). In the toddler and preschool years, sex differences are not as marked as in older children. Boys’ higher rates of disruptive behavior seem to emerge during the later preschool period, with studies docu- menting absence of sex differences from age 1 to 3 (Achenbach, 1992; Keenan & Shaw, 1994), followed by increasing sex dif- ferences from age 4 to 5 (Lavigne, Gibbons, Christoffel et al., 1996; Rose, Rose, & Feldman, 1989). Several studies are available which indicate that early emer- gent behaviour problems are linked with serious behaviour problems later in life (Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1994; Stormont, 2002). In support of this is the finding that 50% to 75% of kindergarten children with significant behaviour problems continue to have these difficulties up to 7 years later (Marakovitz & Campbell, 1998; Speltz, McClellan, DeKlyen, & Jones, 1999). Other research (Zoccolillo, Tremblay, & Vitaro, 1996) has further revealed that the stability and continuity of these behaviour problems can further negatively affect chil- dren’s psychological, cognitive and behavioural outcomes, in- cluding poor academic competence, delinquency and conduct disorder. Individual perceptions of what constitutes problem behavior can also vary. This concern is particularly important because most research on childhood behavior problems utilizes parental reports, and parents’ perceptions of the appropriateness, sever- ity, and quality of their child’s behaviors are influenced by many factors. It is possible that the measurement and assess- ment of behavior problems could be influenced by cultural factors that vary by ethnicity (Spencer, Fitch, Grogan-Kaylor, & McBeath, 2005). In fact, an understanding of the developmental origins of later psychopathology can be gained through research into the early signs of social and emotional dysfunction, and consider- ing that most of our children start to attend preschool institu- tions when they are three years old, we designed the present study to determine prevalence rates of behavioural and emo- tional problems according to parent’s report. Our hypothesis was that there will be differences between the girls and the boys on total problems, internalizing and externalizing. Methodology Sample and Procedure From a total of 755 children, there were 426 boys or 56.4% and 329 girls or 43.6 [(mean age in years = 3.4 (SD 1.0)] from five municipalities (Pristina, Peja, Ferizaj, Mitrovica, Gjilan), who took part in the study. Children ranged in age from 2 to 5 years old (2 = 183 children; 3 = 221 children; 4 = 233 children; 5 = 118 children). There were 755 participants’ parents who voluntarily completed a socio-demographic questionnaire, and rated their child’s behavior on the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 1.5 - 5). The response participation rate was 75.5%. As expected, 639 or 84% of parents were mothers and 116 or 15.4 % were fathers. Table 1 presents the education level and employment rate for both parents. Table 1 shows that from 755 mothers, only 3 of them have the elementary level of education, while 752 of them are very well educated. We can say the same thing for the fathers as well, out of 755, 272 of them have secondary school level while 479 of them have university degree. Table 1. Education level and employment rates for parents. .Nr % Education level mother Elementary 3 0.4 Secondary school 165 21.9 University degree 587 77.7 Education level father Elementary 4 0.5 Secondary school 272 36.0 University degree 479 63.5 Employment situation mother 736 98.1 Employment situation father 752 99.6 Prior to collection of the survey data, we granted the permis- sion for using Kosovar version of CBCL 1.5 - 5. From No- vember 2012 to May 2013 the researcher visited the preschool institutions in five municipalities that were selected from the list provided by Ministry of Education Science and Technology. The researchers met with each preschool director to explain the aim of the study and establish mutual cooperation. Then, the preschool director offered the CBCL to parents of preschool children who attended the preschool institution. Instruments The ASEBA (Achenbach System of Empirically Based As- sessment) preschool forms are standardized assessment instru- ments that are user-friendly, cost-effective, and usable by a wide range of professionals in different settings, which can be completed independently by most respondents in about 15 - 20 min. CBCL 1.5 - 5 were designed to provide normed scores on a wide array of behavioral and emotional problem scales in young children (Rescorla, 2005). The CBCL for preschoolers has been used in over 200 published studies and its validity and reliability are well documented (Rescorla, 2005). Parent ratings were obtained using the CBCL 1.5 - 5 (Achen- bach & Rescorla, 2000), which has 99 items rated 0-1-2 (0 = not true (as far as you know); 1 = somewhat or sometimes true; or 2 = very true or often true) plus 1 open-ended problem items. Ratings of CBCL 1.5 - 5 problem items are based on the chil- dren’s functioning over the preceding 2 months. Parents com- pleted the questionnaires on a voluntary basis at home. They were asked to turn it to the preschool teacher, who collected and sent them to the director. Six syndromes of co-occurring problems were identified for the CBCL 1.5 - 5 through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of item ratings (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). Sec- ond-order factor analysis of the six syndromes yielded two broad-band groupings: Internalizing (comprised of the Emo- tionally Reactive, Anx ious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, and Withdrawn synd rome s) and Externalizing (comprised of the Attention Problems and Aggressive Behavior syndromes). The Total Problems scale is the sum of the ratings on all problem items. Data Analyses T scores and raw scores were assessed using Assessment Data Management (ADM) and all other statistical analyses Open Access 1009  M. SHALA, M. DHAMO were carried out by SPSS version 19 for Windows. Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient was used as an index of internal consis- tency for the CBCL. Scales were described by mean and stan- dard deviation (SD). Multivariate analyses were computed by means of the general linear model (GLM). Results To compare broadband and syndrome scales all CBCL scores were transformed into T-values. Table 2 displays the mean scores, standard deviation and the internal consistency for the seven syndrome scales and the three broad band syndromes. The mean of the CBCL total score of the complete sample was 34.2 (SD = 22.6). As shown in Table 2, there is obviously a high level of internal consistency on both scales. Further on, two main effects, gender and age, had no signifi- cant interaction, F (1) = 2.91, p = .088. There was no significant correlation between the gender of the children and the CBCL total score (rs = −0.03, p = 0.32), while there was a significant correlation between the age of the children and the CBCL total score (rs = 0.13, p = 0.00). The results for mean scores and standard deviations for three broad-band scales by gender are shown in Table 3. The gender differentiated norms leveled the CBCL total scores of boys (Mean = 33.5, SD = 23.1) and girls (Mean = 35.1, SD = 21.9) and there was no significant difference t = 0.98, p = 0.325. It’s the same thing for INT scale, were the t = 1.62, p = 0.106 and also for the EXT scale were t = −0.624, p = 0.533. These results are inconsistent with the hypothesis. The scores of the two broadband scales, for all children, the INT and the EXT scale were significantly correlated: r = 0.66, p < 0.01. We can say the same thing also for girls, were the correla- tion is: r = 0.64, p < 0.01 while for the boys the correlation is r = 0.69, p < 0.01. For the girls the means of the two broadband scales did not differ significantly: INT = 11.6; EXT = 11.2; t = 1.077; p = 0.282. For the boys the mean of EXT (11.5), was significantly higher than the mean of INT (10.6), t = −3.083, p < 0.002. On both broadband scales the means of boys and girls did not differ significantly, INT: Mboys = 10.6, Mgirls = 11.6; t = 1.61, p = 0.106; EXT: Mboys = 11.5, Mgirls = 11.2; t = −0.624, p = 0.533. The results obtained through analysis of variance indicated significant main effects for age. As shown in the Table 4, older children had a higher mean Total Problems score than younger children, F (1) = 5.3, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.02. The ANOVA for internalizing yielded significant main effects for age. Older children had a higher mean internalizing score than younger children F (1) = 6.3, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.02. We can say the same thing for the ANOVA results for externalizing, F (1) = 4.2, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.01. The results obtained through analysis of variance [2 (gender) × 4 (age group)], on seven empirical scores indicated signifi- cant main effects for age, the emotional reactive and somatic complaints indicated significant main effects for gender, while sleeping problems indicated significant main effects on both, gender and age. As shown in the Table 5, the values presented decrease with increasing age of the children, so the younger children have shown the higher mean than older children for all empirical scores. For emotionally reactive, F (1) = 4.2, p < 0.00, η2 = 0.01, age * gender interaction was found significant: F (1) = 5.6, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.02; for anxiety scores, ANOVA indicate the same Table 2. The mean scores, standard deviation and the internal consistency for the syndrome scales and the three broad band syndromes. Mean (SD) Cronbach’s alpha (α) Emotional 2.4 (2.5) 0.88 Anxiety/depression3.5 (2.7) 0.87 Somatic complaint3.1 (2.5) 0.88 Withdrawn 2.0 (2.4) 0.88 Sleep problems 3.0 (2.4) 0.88 Attention problems2.3 (1.8) 0.88 Aggressive behavior9.0 (6.1) 0.86 Internalizing 11.0 (8.6) 0.86 Externalizing 11.4 (7.4) 0.86 Total problems 34.2 (22.6) 0.93 Table 3. Mean scores and standard deviations for three broad-band scales by gender. GenderN Mean SD Comparison Boys-Girls F 32935.1 21.9 Total Problems M 42633.5 23.1 F + M75534.2 22.6 0.325 F 32911.6 8.4 Internalizing M 42610.6 8.8 F + M75511.0 8.6 0.106 F 32911.2 7.6 Externalizing M 42611.5 7.3 F + M75511.4 7.4 0.533 Table 4. Mean scores and standard deviations for three Broad-band scales by age. Internalizing Mean (SD) Externalizing Mean (SD) Total Problems Mean (SD) 2 years 9.7 (9.2) 11.0 (6.8) 32.2 (21.8) 3 years 9.8 (6.6) 10.7 (6.5) 30.9 (17.8) 4 years 12.0 (8.1) 11.3 (7.5) 35.3 (21.5) Age 5 years 13.4 (10.9) 13.5 (9.2) 41.1 (31.2) result: F (1) = 22.7, p < 0.00, η2 = 0.07, age * gender interaction was found significant: F (1) = 3.7, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.01; for withdrawal: F (1) = 6.7 , p < 0.00, η2 = 0.02, , age * gender interaction was found significant: F (1) = 12.4, p < 0.00, η2 =.05; for attention problems: F (1) = 2.9 , p < 0.03, η2 = 0.01, age * gender interaction was found significant: F (1) = 7.2, p < 0.00, η2 = 0.03; and for the aggression: F (1) = 11.5, p < 0.00, η2 = 0.04, age * gender interaction was found significant: F (1) = 9.4, p < 0.00, η2 = 0.04. The sleeping problems and somatic complains indicated sig- nificant main effects for age and gender. Sleeping problems for gender: F (1) = 32.0, p < 0.00, η2 = 0.04; and for age: F (1) = 4.0, p < 0.00, η2 = 0.02. For Age * gender no interactions were significant. Somatic complaints for age: F (1) = 3.2, p < 0.02, η2 = 0.01. Open Access 1010  M. SHALA, M. DHAMO Girls had a higher mean than boys: F (1) = 4.8, p < 0.03, η2 = 0.00. Age * gender interaction was found significant: F (1) = 6.9, p < 0.00, η2 = 0.03. For Internalizing, Externalizing, and Total Problems, we used the clinical range defined as T scores ≥ 64 (about the 90th percentile), the borderline range = T scores from 60 to 63 (84th to 90th percentiles, and the normal range = scores below the 84th percentile (T < 60). With this cut-off, 2.9% of children scored in the deviant range. This percentage provided an estimate of the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems in Kos- ovar children according to parents’ rating. Prevalence rates were 3.8% for Internalizing problems and 2.5% for Externaliz- ing. The results are presented in Table 6 for Internalizing, Ex- ternalizing, and Total Problems by gender and age. Table 6 shows the prevalence rate for scores above the cut-off for deviance on Internalizing, Externalizing, and Total Problems separately by gender and age. For Internalizing, prevalence was higher for girls than boys and for three, four year old children higher than for younger and older children. For Externalizing, prevalence was much higher for boys than girls, and slightly higher for younger children than older chil- dren. For Total Problems, prevalence was slightly higher for girls than boys, and there is a big difference for four years old children, while for the other groups the prevalence is compara- ble. Discussion With a very low rate, only 2.9% of the preschool children were in the clinical range on the CBCL 1.5 - 5. In comparison to a previous research with 360 children from the municipality of Pristine (Jetishi, 2010), using the same measure, this rate is low. Within the previous study (Jeshiti, 2010) the prevalence rate for total problem scores were 7.2% in the clinical range, while in this study 2.9. This can be explained with the fact that our research included 755 children from five different munici- palities of Kosovo, all children who already attend a preschool education program, which is expected to have its impact on Table 5. Means and standard deviation for seven empirical scales, according to gender and age. Gender Age Girl Mean (SD) Boys Mean (SD) 2 years Mean (SD) 3 years Mean (SD) 4 years Mean (SD) 5 years Mean (SD) Emotional 2.5 (2.6) 2.2 (2.4) 1.8 (2.6) 2.2 (2.2) 2.5 (2.2)3.0 (3.1) Anxiety/ depression 3.7 (2.8) 3.4 (2.7) 3.3 (3.0) 3.2 (2.3) 3.7 (2.8)4.1 (2.8) Somatic complaint 3.4 (2.3) 2.9 (2.7) 2.8 (2.4) 2.9 (1.8) 3.2 (2.4)3.7 (3.5) Withdrawn 2.0 (2.4) 2.0 (2.5) 1.7 (2.5) 1.5 (1.9) 2.6 (2.3)2.5 (2.9) Sleep problems 3.5 (2.7) 2.6 (2.1) 2.9 (2.6) 2.7 (2.4) 2.9 (1.9)3.6 (2.9) Attention problems 2.4 (1.9) 2.4 (1.8) 2.1 (1.7) 2.2 (1.6) 2.4 (1.8)2.8 (2.4) Aggressive behavior 8.9 (6.2) 9.2 (5.9) 8.9 (5.7) 8.5 (5.4) 8.8 (6.2)10.7 (7.1) Table 6. Prevalence (%) of scores above the cut-off for Internalizing, External- izing, and Total Problems by gender and age. Internalizing Externalizing Total Problems Nr. % Nr. % Nr. % Boys 15 3.2 21 4.4 20 4.2 Girls 15 4.6 5 1.5 15 4.6 2 years 8 4.4 6 3.3 8 4.4 3 years 13 5.9 7 3.2 10 4.5 4 years 11 4.7 7 3.0 4 1.7 5 years 5 4.2 3 2.5 5 4.2 Total 29 3.8 19 2.5 22 2.9 child development and behavior. However, the other demo- graphic variables should be considered. We can say the same thing for the comparison with interna- tional studies, with research showing the range from 7% - 25% (Angold & Egger, 2004) and 11.9% of Turkish Children (Erol et al., 2005). The prevalence rate of this study was too far from the range of 10% - 15% reported by Campbell (1995) and from 10.2%, which was the mean prevalence in preschool studies reviewed by Roberts et al. (1998). Notwithstanding cross-national comparisons of studies, it is of interest in the current study that the mean Total Problems score of 34.2 (SD = 22.6) for 2 - 5 years old Kosovar children was slightly higher than the mean Total problems score for Dutch children, which was 30.5, also for 466 Italian children it was 33.4 (Frigerio et al., 2006), for 374 Finnish children (Sourander, 2001), was 30.4, while for 109 Icelandic children the mean score was 27.5 (Hannesdóttir & Einarsdóttir, 1995) and for 756 Quebec children, it was 32.9 (Larson et al., 1988). On the other side, our result was lower than in some other studies. Namely, the mean Total Problems score for 169 Span- ish children from the general population, was 37.6 (De la Osa, Ezpeleta, & Navarro, 1996), while Erol et al. (2005) obtained a total problems mean score of 39.5 for 638 Turkish children assessed with CBCL 2 - 3. There was an obvious tendency of increase of internalizing values within the age, which could be explained and may re- flect improvements in the capacity to remember and anticipate negative events (Kaslow, Brown, & Mee, 1994). For external- izing problems there was a slight decrease of values, which corresponds with developing language and cognitive abilities that permit the use of emotion regulation strategies other than physical aggression to settle disputes. Regarding the gender differences there was no statistical significance for any of the three broad band syndromes. This was in line with a body of studies (Campbell, 1995; Keiley et al., 2000; Richman et al., 1982), that there are no gender differences in preschool children, and disagreed with some other studies, which reported that boys tend to demonstrate a significantly higher propensity to mani- fest externalizing problems than girls (Prior, Smart, Sanson, & Oberklaid, 1993; Sanson, Oberklaid, Pedlow, & Prior, 1991). In our context, having into consideration that out of 755, 639 respondents were mothers, and that our mentality encourages boys to be more lively, more active than girls, this result is of interest to further studies. Also from the fact that we used only parent’s report, while it has been argued that multi-informant assessment of children may offer a more comprehensive under- Open Access 1011  M. SHALA, M. DHAMO standing of children’s problems (Kagan, Snidman, McManis, Woodward, & Hardway, 2002), and that modest to moderate strength of correlations across informants and across settings (Achenbach, Edelbrock, & Howell, 1987; Grietens et al., 2004) may reflect true variations in children’s behaviors across dif- ferent settings and interpersonal relationships (Kerr, Lunken- heimer, & Olson, 2007; Merrell, 1999), we strongly recom- mend a multi-informant assessment of Kosovar preschool chil- dren. Limitations Despite the large sample size, restrictions must be made about the generalizability of the findings. The study sample was derived from preschool institutions and there is a very low per- centage of preschool attendance in Kosovo. The educational levels of parents and a predominantly middle class bias were specific features of the sample. Also the rate of employment was clearly higher than the national average. When interpreting the results, it should be taken into account that the child mental health status was assessed by a symptom checklist questionnaire. Given the large number of subjects, the questionnaire approach offers useful information but lacks the specificity and additional depth that structured psychiatric in- terviews might provide. Further studies on preschool children behavior problems are strongly recommended in order to understand the continuity and discontinuity of CBCL scores as the children develop. Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants in the study as well as preschool institution directors and teachers. We would also like to express special appreciation to Emina Hyseni for continuous support with translation and proofreading. REFERENCES Achenbach, T. M., Mc Conaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/Adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psycho- logical Bulletin, 101, 213-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.213 Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. Achenbach, T. M. (1992). Manual for child behavior checklist/2-3 and 1992 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. Angold, A., & Egger, H. L. (2004). Psychiatric diagnosis in preschool children. Baillargeon, R. H., Zoccolillo, M., Keenan, K., Côté, S., Pérusse, D., Wu, H. X., Boivin, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2007). Gender differences in physical aggression: A prospective population-based survey of chil- dren before and after 2 years of age. Developmental Psychology, 43, 13-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.13 Campbell, S. B. (1995). Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychia- try, 36, 113-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x Dearing, E., McCartney, K., & Taylor, B. A. (2006). Within-child associations between family income and externalizing and internal- izing problems. Developmental Psychology, 42, 237-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.237 Duncan, G., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Klebanov, P. (1994). Economic depri- vation and early-childhood development. Child Development, 65, 296-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1131385 Erol, N., Sinsek, Z., Oner, O., & Munir, K. (2005). Behavioral and emotional problems among Turkish children at ages 2 to 3 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychia- try, 44, 81-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000145234.18056.82 Frigerio, A., Cozzi, P., Pastore, V., Molteni, M., Borgatti, R., & Mon- tirosso, R. (2006). The evaluation of behavioral and emotional prob- lems in a sample of Italian preschoolers using the Child Behavior Checklist and the Caregiver-Teacher Report Form. Infanzia e Ado- lescenza, 5, 24-32. Grietens, H., Onghena, P., Prinzie, P., Gadeyne, E., Assche, V. van, Ghesquiére, P., & Hellinckx, W. (2004). Comparison of mothers’, fathers’, and teachers’ reports on problem behavior in 5- to 6- year-old children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral As- sessment, 26, 137-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000013661.14995.59 Hannesdottir, H., & Einarsdottir, S. (1995). The Icelandic Child Mental Health Study: An epidemiologic study of Icelandic children 2 - 18 years of age using the Child Behavior Checklist as a screening in- strument. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 4, 237-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01980488 Hinshaw, S. P. (2002). Process, mechanism, and explanation related to externalizing behavior in developmental psychology. Journal of Ab- normal Child Psychology, 30, 431-446 http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1019808712868 Hoffmann, J., & Su, S. (1997). The condition-al effects of stress on delinquency and drug use: A strain theory assessment of sex differ- ences. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 34, 46-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022427897034001004 Jetishi, P. (2010). Emotional and behavioral problems in children of preschool age 2 - 5 years. MA Thesis, Pristina: Pristina University. Kaslow, N. J., Brown, R. T., & Mee, L. L. (1994). Cognitive and be- havioral correlates of childhood depression: A developmental per- spective. In W. M. Reynolds, & H. F. Johnston (Eds.), Handbook of depression in children and adolescents (pp. 97-121). New York: Plenum Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1510-8_6 Kagan, J., Snidman, N., McManis, M., Woodward, S., & Hardway, C. (2002). One measure, one meaning: Multiple measures, clearer meaning. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 463-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579402003048 Keiley, M. K., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2000). A cross-domain growth analysis: Externalizing and internalizing be- haviors during 8 years of childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 161-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1005122814723 Keenan, K., & Shaw, D. (1994). The development of aggression in toddlers: A study of low income families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 22, 53-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02169256 Keenan, K., & Shaw, D. (1997). Developmental and social influences on young girls’ early problem behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 95-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.95 Kerr, D. C. R., Lunkenheimer, E. S., & Olson, S. L. (2007). Assessment of child problem behaviors by multiple informants: A longitudinal study from preschool to school entry. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 967-975. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01776.x Keenan, K., & Shaw, D. S. (2003). Starting at the beginning: Exploring the etiology of antisocial behaviour in the first years of life. In B. J. Lahey, T. E. Moffitt, & A. Caspi (Eds.), Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency (pp. 153-181). New York: Guildfo. Larson, C. P., Pless, I. B., & Miettinen, O. (1988). Pre-school behavior disorders: their prevalence in relation to determinants. The Journal of Pediatrics, 113, 278-285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(88)80265-8 Lavigne, J. V., Gibbons, R. D., Christoffel, D., Arend, R., Rosenbaum, D., Binns, et al. (1996). Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric disorders amongst preschool children. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 204-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199602000-00014 Open Access 1012  M. SHALA, M. DHAMO Open Access 1013 Luk, S.L., Leung, P., Bacon-Shone, J., & Leih-Mak, F. (1991). The structure and prevalence of behavioral problems in Hong Kong pre- school children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19, 219-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00909979 Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Grow-wing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Marakovitz, S. E., & Campbell, S. B. (1998). Inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity from preschool to school age: Performance of hard-to-manage boys on laboratory measures. Journal of Child Psy- chology and Psychiatry, 39, 841-851. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00385 Merrell, K. W. (1999). Behavioral, social, and emotional assessment of children and adolescents. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associ- ates, Inc. Mesman, J., Bongers, I., & Koot, H. M. (2001). Preschool develop- mental pathways to preadolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 679-689. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00763 National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2005). Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the developing brain: Working Pa- per #2. http://www.developingchild.net Osa, N. de la, Ezpeleta, L., & Navarro, J. B. (1996). Adaptación y baremos del Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/2-3) para preescolares espa-oles: Resultados preliminares. Ciencia Psicológica, 4, 19-31. Prior, M., Smart, D., Sanson, A., & Oberklaid, F. (1993). Sex differ- ences in psychological adjustment from infancy to eight years. Jour- nal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 291-304 http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199303000-00009 Richman, N., Stevenson, J., & Graham, P. (1982) Preschool to school: A behavioural study. London: Academic Press Roberts, R. E., Attkisson, C. C., & Rosenblatt, A. (1998). Prevalence of psychopathology among children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 715-725. Rose, S. L., Rose, S. A., & Feldman, J. F. (1989). Stability of behavior problems in very young children. Development and Psychopathology, 1, 5-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400000213 Sanson, A., Oberklaid, F., Pedlow, R., & Prior, M. (1991). Risk indica- tors: Assessment of infancy predictors of pre-school behavioural maladjustment. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 32, 609- 626. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00338.x Speltz, M. L., McClellan, J., DeKlyen, M., & Jones, K. (1999). Pre- school boys with oppositional defiant disorder: Clinical presentation and diagnostic change. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 838-845. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199907000-00013 Spencer, M. S., Fitch, D., Grogan-Kaylor, A., & McBeath, B. (2005). The equivalence of the Behavior Problem Index across U.S. ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 573-589. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022022105278543 Stormont, M. (2002). Externalizing behavior problems in young chil- dren: Contributing factors and early intervention. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 127-138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pits.10025 Sourander, A. (2001). Emotional and behavi-oural problems in a sam- ple of Finnish three-year-olds. European Child and Adolescent Psy- chiatry, 10, 98-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s007870170032 Zoccolillo, M., Tremblay, R., & Vitaro, F. (1996). DSM-III-R and DSM-III criteria for conduct disorder in preadolescent girls: Specific but insensitive. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Ado- lescent Psychiatry, 35, 461-470. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199604000-00012

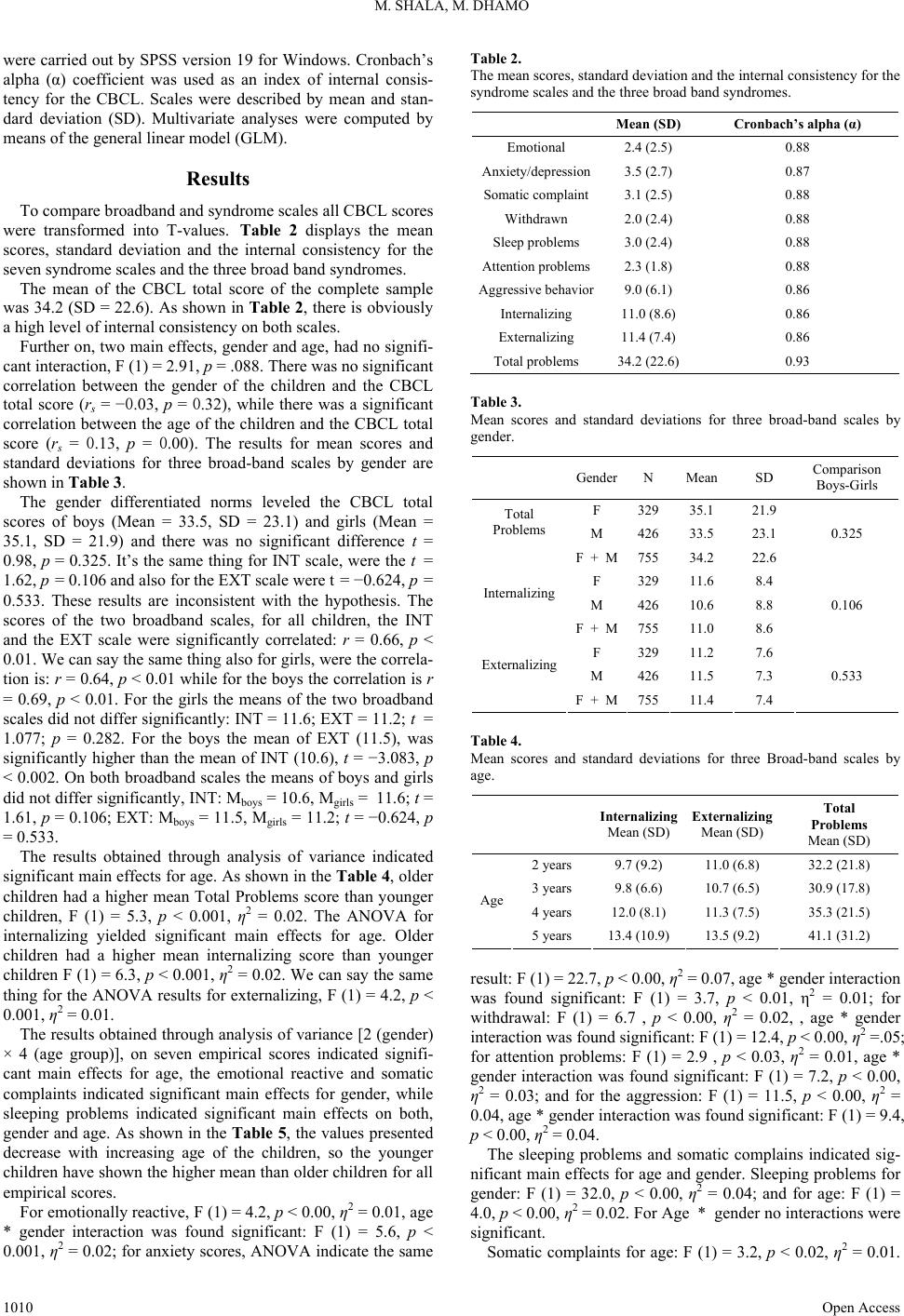

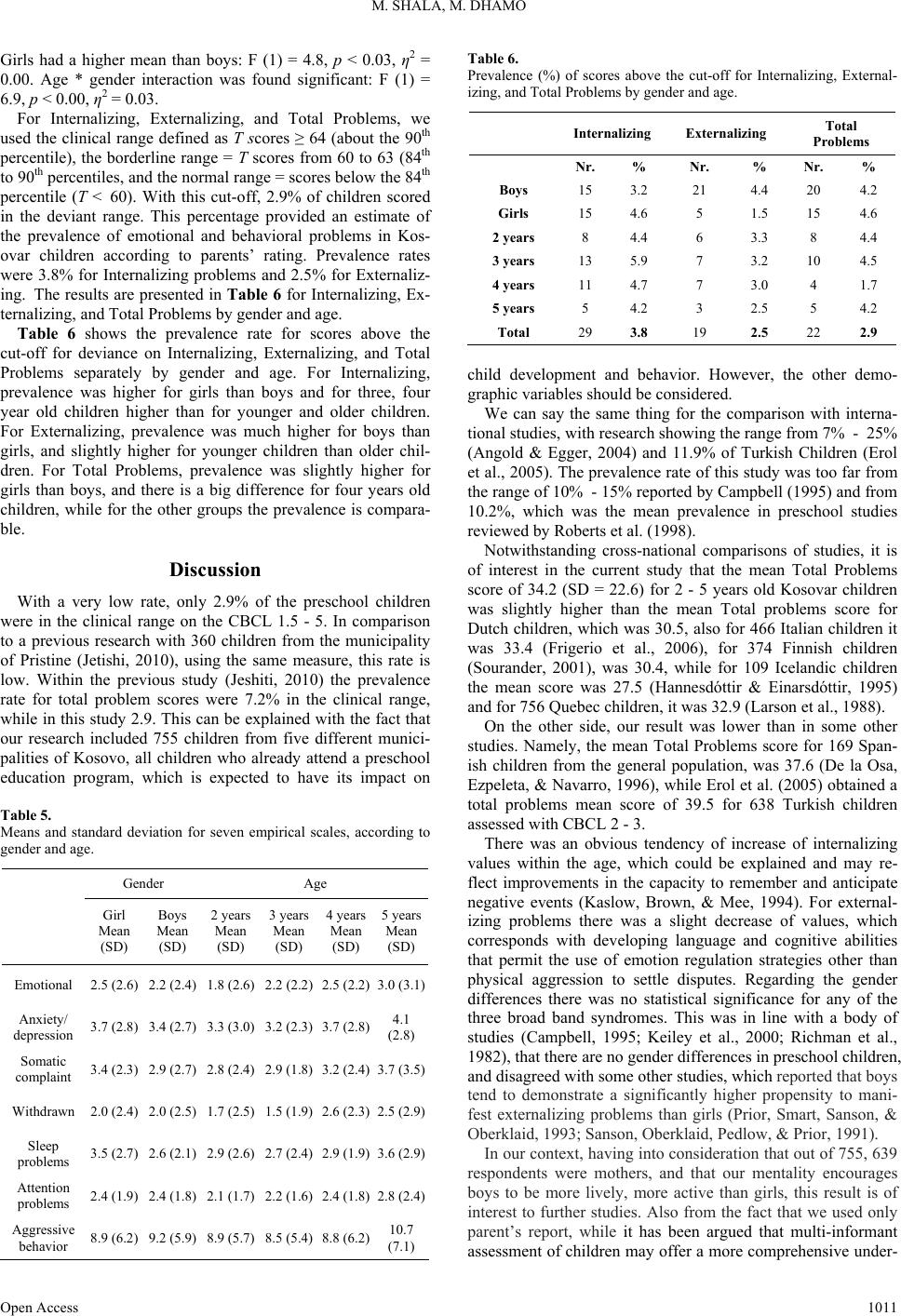

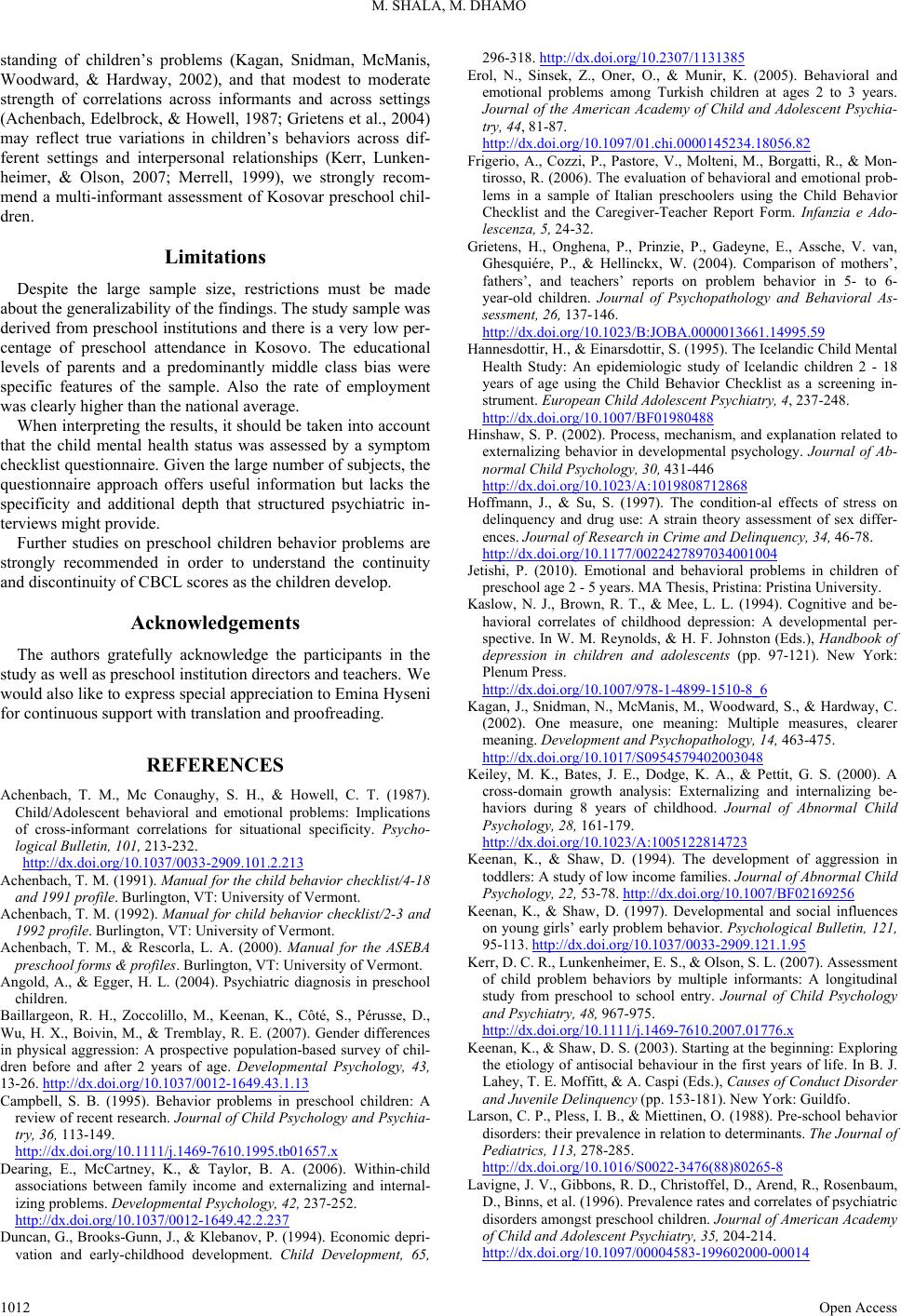

|