Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.12, 975-984 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.412141 Open Access 975 Behavioral and Experiential Self-Regulations in Psychological Well-Being under Proximal and Distal Goal Conditions Peter Horvath, Vanessa McColl Department of Psychology, Acadia University, Wolfville, Canada Email: Peter.Horvath@acadiau.ca, 095006m@acadiau.ca Received August 15th, 2013; revised September 18th, 2013; accepted October 13th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Peter Horvath, Vanessa McColl. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Peter Horvath, Vanessa McColl. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. This study examined the relationship of goal-related components of cybernetic, behavioral, and experien- tial self-regulations to psychological well-being under two types of conditions, the pursuit of intrinsic goals in general and specific intrinsic goals for the academic term. In an online survey, undergraduates (N = 186) completed global measures of psychological well-being, behavioral and experiential self-regula- tions, and rated themselves on goal-related self-regulatory components. Correlations indicated that most of the cybernetic, behavioral and experiential self-regulatory variables were associated with each other and with well-being. In terms of the goal-related self-regulatory components, when pursuing intrinsic goals more generally, the experiential self-regulatory component of enjoyment of the activity predicted well-being. However, when pursuing intrinsic term goals, the cybernetic self-regulatory component of perceived goal progress and the behavioral self-regulatory component of self-reinforcement for goal pro- gress predicted well-being. The findings extend theoretical conceptualizations of psychological well-be- ing by integrating compatibilities between cybernetic, behavioral, experiential self-regulatory processes and motivational conditions. Keywords: Self-Regulation; Motivation; Goal Conditions; Psychological Well-Being Introduction The present study examined the relationships of behavioral and experiential self-regulatory components to psychological well-being under proximal and distal goal conditions. Both ex- periential and cognitive-behavioral processes have been pro- posed to account for the antecedents of psychological well- being in theories of motivation and self-regulation (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999; Sheldon & Kasser, 1995, 1998). Striving for goals is one of the central features in cybernetic, behavioral, and ex- periential self-regulation. However, few studies have examined the compatibilities of such self-regulatory processes with dif- ferent goal conditions for the promotion of well-being. As a consequence, our understanding of the relationship between selfregulation, goal striving, and well-being remains frag- mented and incomplete. The present study makes use of con- strual-level theory (CLT; Liberman & Trope, 1998; Trope & Liberman, 2010; Trope, Liberman, & Wakslak, 2007) to exam- ine these relationships under proximal and distal goal condi- tions. Construal-level theory proposes that individuals make use of general and abstract constructs to conceptualize psycho- logically distant objects, and specific and concrete constructs to conceptualize psychologically close objects. According to CLT, general constructs represent the core features of objects and goals. Specific constructs represent the peripheral features of objects and goals. Construal-level theory has also been applied to examining the psychological correlates of different types of goals. For example, research has shown that general, abstract, and distal goals are associated with experiential attributes such as desirability, enjoyment, and interest. Whereas more specific, concrete, and proximate goals are associated with behavioral diensions such as the feasibility and efficiency to achieve goals (Trope et al., 2007). Accordingly, under distal goal conditions, we proposed that core aspects of motives would be activated which would be compatible with experiential self-regulation. Under proximal goal conditions, however, peripheral aspects of motives would be activated, compatible with behavioral and cy- bernetic self-regulation. One would expect that closer match on attributes shared by a goal condition and components in self-regulation would be adaptive and associated with greater psychological well-being. For example, specific goals in situations are compatible with cognitive and behavioral self-regulatory processes that depend on feedback and control. On the other hand, general or abstract goals have core attributes such as desirability that is compatible with experiential self-regulatory processes that involve intrin- sic interests. Accordingly, one would predict that under circum- scribed conditions, such as in the pursuit of short-term goals in specific situations, cybernetic and behavioral components in self-regulation, such as perception of goal progress and self- reinforcement, would be associated with well-being. In the pur- suit of goals more generally, however, experiential components in self-regulation, such as enjoyment of an activity, would be associated with well-being.  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL Motivational Content Current studies on motivation have drawn distinctions be- tween motivational content (e.g., interests and goals) and proc- esses of self-regulation, or the ways and reasons for acting on them (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Sheldon & Elliot, 1999; Sheldon & Kasser, 1995, 1998; Sheldon, Ryan, Deci, & Kasser, 2004). Motivational content has been formulated in various but com- plementary ways in the literature. Proponents of Self-Determi- nation Theory (SDT) have differentiated between intrinsic goals which are pursued because they are inherently enjoyable and extrinsic goals which are pursued for secondary reasons (Deci & Ryan, 1987; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Carver and Scheier (1998) placed goal pursuits in a hierarchy, from ideal and gen- eral goals at the top to specific routines, programs, scripts, and behaviors at the bottom. The general goals are pursued through the execution of specific and concrete acts at the bottom of the hierarchy. A related differentiation considers whether one is pursuing distal or proximal goals (Locke & Latham, 2002; Zimmerman & Schunk, 2001). The external situation is seen as more salient for individuals pursuing proximal rather than distal goals. Others have differentiated between implicit and explicit goals and motives (Thrash & Elliot, 2002). Implicit motives are based on internal needs and are less in conscious awareness whereas explicit motives are consciously formulated. The for- mer is better at predicting long-term behaviors and achieve- ment whereas the latter is better at predicting short-term be- haviors or what people will do in specific situations (Spangler, 1992). Behavioral and Cybernetic Self-Regulation Self-regulation has been generally conceptualized as the management and control of behavior in order to acquire goals selected by the individual (Bandura, 1997; Carver & Scheier, 1998; Endler & Kocovski, 2000; Kanfer, 1970). Theories on self-regulation were developed within behavioral, cognitive, and cybernetic theories and models (Bandura, 1997; Carver & Scheier, 1998; Kanfer, 1970). The components of cybernetic and behavioral self-regulation include goal setting, planning, feedback, self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-reinforce- ment (Endler & Kocovski, 2000; Febbraro & Clum, 1998; Ko- covski & Endler, 2000; Mezo, 2009). Striving for goals is a core aspect of self-regulation and is thought to energize and guide behavior (Carver & Scheier, 1998; Locke & Latham, 2002). Behavioral and cybernetic self-regulation share similar processes involving the control of behavior to acquire desired goals. In cybernetic regulation, however, there is relatively more emphasis on cognition and the role of information feed- back to guide behavior, while in behavioral regulation there is relatively more focus on the use of motivational components such as self-reinforcement. However, unlike enjoyment in ex- periential self-regulation, in behavioral self-regulation the re- ward is externally applied and the consequent experience of pleasure is seen as differentiated from the act being reinforced. For example, one student might study for a course because of intrinsic interest in the material itself, whereas another student might use externally applied incentives to persist in his study. In both cybernetic and behavioral self-regulation, behavior is adjusted to eliminate discrepancies from set goals (Carver & Scheier, 1998; Endler & Kocovski, 2000). The proximity of behaviors to valued goals is a determinant of adjustment, self- worth, and positive affect (Ahrens, 1987; Hyland, 1987; Siegert, McPherson, & Taylor, 2004). In cybernetic theory, positive affect occurs when the person perceives that adequate progress is being made toward goals (Carver & Scheier, 1998). In con- trast, negative affect occurs if the person does not perceive that adequate progress is being made. A meta-analysis of relevant research has confirmed that goal progress is associated with increased positive and decreased negative affect (Powers, Koestner, Lacaille, Kwan, & Zuroff, 2009). Perceived goal progress in behavioral self-regulation can lead to subsequent self-reinforcement (Endler & Kocovski, 2000; Kocovski & Endler, 2000). Positive self-evaluations and self-reinforcement for reaching goals result in positive affect (Ahrens, 1987; Endler & Kocovski, 2000; Kocovski & Endler, 2000). On the other hand, low frequencies of self-reinforcement in behavioral self-regulation are associated with emotional distress and de- pression (Kocovski & Endler, 2000). Experiential Self-Regulation Self-Determination Theory describes the motivational and experiential self-regulatory processes involved in satisfying core and peripheral needs and desires (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000). High self-determined motivation is asso- ciated with the capacity and freedom to select and pursue in- trinsically interesting goals rather than extrinsic ones (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Owens, Mortimer, & Finch, 1996; Ryan & Deci, 2000). From the perspective of SDT, individuals have a pro- pensity to satisfy basic or primary needs for autonomy, compe- tence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 1987; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Goals and interests that meet these basic psychological needs are intrinsically motivating and satisfying. In intrinsic motivation the reward is the spontaneous experience of interest and enjoyment (Deci & Ryan, 1995; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Ex- amples of intrinsic motivation include the pursuit of goals for affiliation, personal growth, and community relations. In con- trast, extrinsic motivation includes the pursuit of goals for wealth, fame, and self-image that at best indirectly satisfy basic needs. According to SDT, experiential self-regulation has been con- ceptualized to function along a controlled and externally regu- lated to an autonomously and internally regulated continuum (Deci & Ryan, 1987; Deci, Eghrari, Patrick, & Leone, 1994). Experiential self-regulations vary in the degree to which the person pursues motives and values that have been internalized and integrated all the way from amotivation and extrinsic regu- lation to intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). To reflect these processes, global measures have been developed to assess six levels of experiential self-regulation from amotivation to in- trinsic motivation (see Pelletier et al., 2007). Based on theoretical and empirical grounds, however, some researchers have also conceptualized autonomous and con- trolled regulation as separate experiential self-regulatory proc- esses (Barbeau, Sweet, & Fortier, 2009; Koestner, Otis, Powers, Pelletier, & Gagnon, 2008). Autonomously regulated individu- als feel free and empowered to choose intrinsically satisfying goals and are likely to enjoy their activities (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Sheldon & Elliott, 1999; Sheldon et al., 2004). Autonomous regulation is associated with positive self-esteem (Owens et al, 1996; Sheldon & Kasser, 1995) and psychological well-being (Ratelle, Vallerand, Chantal, & Provencer, 2004; Sheldon et al., 2004; Sheldon & Kasser, 1995). In contrast, individuals using Open Access 976  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL controlled regulation choose their goals in response to external forces. They perceive external constraints or demands to which they feel compelled to conform. In controlled regulation the individual does not feel free to choose intrinsically satisfying goals. In such circumstances, the individual is less likely to be motivated, satisfied, or successful. The pursuit of extrinsic or externally imposed goals results in less effort, basic need ful- fillment, and well-being (Crocker, Brook, Niiya, & Villacorta, 2006; Sheldon et al., 2004). Self-Regulation and Goal Types Certain goal types or conditions appear to be more com- patible with some forms of self-regulation than others. Behav- ioral and cognitive forms of self-regulation tend to be applied to the situational requirements of goal pursuits (Locke & Latham, 2002; Zimmerman & Schunk, 2001). Behavioral strategies and tactics make it more likely that goals will be reached in specific situations. For example, implementation planning has been found to increase progress on goals and to achieve behavioral change within short time intervals (Koestner et al., 2008). Per- ception of goal progress, in turn, has resulted in increased well-being within short time intervals (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999; Sheldon & Kasser, 1998). In contrast, experiential aspects of self-regulation, such as intrinsic enjoyment of an activity, ap- pear to play a more prominent role in promoting adjustment and well-being in the pursuit of long-term goals. Experiential self- regulation has been found to predict well-being after a time in- terval of one year (Sheldon et al., 2004), whereas its effects on well-being in short time intervals of one or two-weeks were mixed (Sheldon & Kasser, 1995, 1998). These findings suggest that the effects of different types of self-regulations on well- being may depend on the types of goals individuals are pursu- ing and the situations to which they apply. The above reviewed findings point towards two observations. First, the conceptualizations of goals fall into two main types. More general, distal, and implicit goals, although not identical, appear to be similar constructs. Likewise, more specific, prox- imate, and explicit goals appear to be similar constructs. Sec- ond, different self-regulatory processes appear to have dif- ferential applicability and effectiveness in addressing these two types of goals. Some evidence suggests that experiential self- regulation might be more appropriate for general, distal, and implicit goal pursuits. On the other hand, behavioral and cogni- tive self-regulation has been successfully applied to specific, proximal, and explicit goals in more circumscribed situations. Accordingly, general and long-term goals reflect core attributes which appear to be compatible with experiential self-regulation. In contrast, specific and short-term goals contain situational requirements which appear to be compatible with cybernetic and behavioral self-regulations. The Present Study We proposed that psychological well-being is related to compatibilities between self-regulatory processes and different types of goal pursuits. We make this proposal based on several considerations and findings in the literature. In specific situa- tions, a sense of accomplishment might come from success on specific tasks. Positive feedback and consequent reinforcement for success likely promote self-esteem and other psychological benefits in circumstances where cybernetic and behavioral self-regulations are used. Cybernetic and behavioral self-regu- lations, however, differ in their emphases on the use of infor- mation and external rewards to control behavior. Accordingly, their effects on well-being should be tested separately. On the other hand, components of experiential self-regulation, such as intrinsic enjoyment of an activity, are likely to be more effect- tive in promoting well-being in the pursuit of goals more gen- erally because they can sustain the individual emotionally over long periods of striving. We, therefore, proposed that percep- tion of goal progress and self-reinforcement for progress, com- ponents in cybernetic and behavioral self-regulation, would be associated with psychological well-being in the pursuit of short-term goals. On the other hand, enjoyment of the activity, a component in experiential self-regulation, would be associ- ated with psychological well-being in the pursuit of goals more generally. Our participants completed global measures on their typical modes of behavioral and experiential self-regulations, as well as measures of psychological well-being. They also listed im- portant intrinsic goals they pursued more generally and in the short-term and rated their use of components found in cyber- netic, behavioral, and experiential self-regulation, including perceptions of goal progress, self-reinforcement for goal pro- gress, and enjoyment of goal pursuits. The study employed self-report measures of mental health, self-esteem, and general affect to form a composite index of psychological well-being. These measures are well-known indicators of subjective well- being (Koestner et al., 2008; Ratelle et al., 2004). Hypotheses We hypothesized that in the pursuit of goals more generally, active components in experiential self-regulation, such as en- joyment of the activity, would be associated with psychological well-being. On the other hand, in more circumscribed situations, such as in the pursuit of short-term goals, active components in cybernetic and behavioral self-regulations, namely perception of goal progress and self-reinforcement for goal progress, would be associated with psychological well-being. Method Participants A total of 186 volunteer undergraduates (144 females, 42 males), ages ranging from 18 to 44 years (M = 19.68, SD = 2.60) participated in the online study. Subsequently, two subsamples were formed to examine the relationships of goal conditions with psychological well-being under general and term goal con- ditions. The demographic profiles of the two subsamples are presented in Table 1. Measures Demographic Information. A questionnaire was used to ob- tain information on age, gender, marital status, ethnic back- ground, year of university, and college major. Global Motivation Scale (GMS). Following Pelletier et al. (2007), a shortened version of the Global Motivation Scale (Guay, Mageau, & Vallerand, 2003) was used to assess global self-determined motivation or experiential self-regulation. This 18-item version is divided into six subscales (three items per Open Access 977  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL Table 1. Demographic variables in the general goals and term goals subsamples. Subsamples General Goals Term Goals Ethnicity Caucasian 79.8% 79.6% Native Canadian 1.1% 2.2% Asian 6.7% 6.5% African 5.6% 4.3% Other 5.6% 6.5% Not Reported 1.1% 1.1% Marital Status Married 1.0% 0.0% Common-Law 1.0% 1.1% Divorced 1.0% 1.1% Single 95.5% 96.8% Not Reported 1.0% 1.1% University Level First Year 62.9% 59.0% Second Year 13.5% 15.1% Third Year 4.5% 6.5% Fourth Year 14.6% 15.1% Fifth Year 4.5% 4.3% University Major Psychology 17.0% 20.4% Other 83.0% 79.6% subscale) that represent the six subtypes of experiential self- regulation described by Deci and Ryan (1985): intrinsic moti- vation, integrated regulation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, external regulation, and amotivation. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each item corre- sponds to their own reasons for performing different activities using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not corre- spond at all) to 7 (corresponds exactly). The GMS was reported to have satisfactory internal consistency with an α coefficient of 0.87 (Ratelle et al, 2004). Global self-determination has been shown to have acceptable temporal reliability (0.72) over a six-week period and to predict success at a wide range of be- haviors including controlling one’s emotions, exercising, and studying—activities that require self-regulation (Pelletier et al., 2007). Two composite experiential self-regulatory variables were formed following the descriptions given by Deci and Ryan (1987, 2000) and confirmed by principal components factor analyses in our study and in previous research (Barbeau et al., 2009). An autonomous regulation variable was created by summing the scores of the identified regulation, integrated re- gulation, and intrinsic motivation subscales and then dividing this score by three. Similarly, a controlled regulation variable was created by summing the scores for the external regulation and introjected regulation subscales and dividing by two. We included these two variables in our study to examine the con- struct validity of our goal-related ratings. Self-Reinforcing Subscale (SRS). The Self-Control and Self-Management Scale (SCMS; Mezo, 2009) is a 16-item global measure of the general use of behavioral self-regulation and its three components. Established through a combination of rational and factor-analytic item derivation methods, six items measure self-monitoring, five items measure self-evaluation, and five items measure self-reinforcement. The SCMS is scored on a 6-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more self-control and self-management skills. The scale anchors range from 1 (very undescriptive of me) to 5 (very descriptive of me). Mezo (2009) reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.81 for the overall scale and moderate to high convergent validity with other measures. He also reported a Cronbach α of 0.78 and a test-retest correlation of 0.70 for the Self-Reinforcing Subscale (SRS) and significant correlations with other self-control and symptom measures in undergraduates. As our study mainly focused on the control and motivational aspects of behavioral self-regulation, we used only the Self-Reinforcing Subscale. An example of an item from the self-reinforcement scale is, “I con- gratulate myself when I make some progress”. We included this global variable in our study to examine the construct validity of our goal-related ratings. Goal Conditions. First, participants were provided with a definition of personal goals (Koestner et al., 2008) as well as a brief description of intrinsic goals that included some examples (see Ryan, Huta, & Deci, 2008; Wicker. Hamman, Reed, McCann, & Turner, 2005). Next, participants were asked to list their most important intrinsic goals (goals pursued more gener- ally), providing at least three and a maximum of five. Partici- pants were then also asked to list the most important intrinsic goal they were striving for that academic term. We examined the obtained lists of goals based on definitions of intrinsic and extrinsic goals given by self-determination re- searchers (Ryan et al., 2008; Wicker et al., 2005). We discov- ered that some participants not only listed intrinsic but also extrinsic general and term goals. Examples of intrinsic goals provided by the participants in the current study included, “help others”, “build strong relationships with friends and family”, and “make new friends”. Examples of extrinsic goals included, “get wealthy”, “high GPA”, and “pass everything”. Based on agreed upon definitions of intrinsic and extrinsic goals, two researcher independently coded the general and term goals as either intrinsic or extrinsic. For the general goals, if a partici- pant gave even one extrinsic goal, their total goal list was rated as extrinsic. Otherwise it was coded as intrinsic. The inter-rater reliability coefficient for the coding of the term goals was 0.91. The inter-rater reliability coefficient for the coding of the gen- eral goals was 0.80. Subsequently, two selected goal subsamples were created for analyses. The first subsample was created to examine the hy- pothesis for general intrinsic goals. The second subsample was created to examine the hypothesis for the term intrinsic goals. In forming the two subsamples, participants with extrinsic goals of the same type (general or term) as those characterizing the particular goal subsample (general or term) were excluded, thereby strengthening the intrinsic goal type of the particular sample. By focusing on intrinsic goals, we could control this goal dimension (intrinsic vs extrinsic) and thereby better test the relationship of well-being to compatibilities between our main goal dimension of interest (general vs term) and different self-regulatory components. The subsequent general intrinsic goals subsample consisted of 89 participants (71 females, 18 males) between 18 to 44 years (M = 20.13, SD = 3.39). As described above, ninety-seven participants from the whole sample who listed at least one ex- trinsic general goal were excluded in forming this subsample. Open Access 978  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL The term intrinsic goal subsample consisted of 93 participants (73 females, 20 males) between 18 to 44 years (M = 20.00, SD = 3.09). Similarly to the above criterion, 93 participants in the whole sample who listed an extrinsic term goal were excluded from this subsample. Although there was some overlap in the two subsamples, as all participants had been originally asked to list both their general and term goals, we did not feel this af- fected the results. Goal Progress. Participants were asked to rate on two sepa- rate scales how much “progress overall” or in general they had made towards their most important intrinsic goals and how much progress they had made towards their “intrinsic goal for the term”, using 9-point Likert rating scales, ranging from 0 (none) to 8 (a great deal). We expected that their goal self- ratings would reflect the actual behavior of the participants. Feelings of Enjoyment. Using 8-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (none) to 8 (a great deal), participants were asked to rate how much acting on their intrinsic goals generally and on their intrinsic goal for the term led to feelings of enjoyment. Three items were used to assess participants’ feelings of en- joyment generally from acting on their intrinsic goals: “Rate how much acting on your intrinsic goals typically leads to feel- ings of enjoyment”, “...feelings of pleasure”, and “feelings of satisfaction”. The sum of these three items was used to calcu- late a total score for feelings of enjoyment generally from act- ing on intrinsic goals, with higher scores reflecting greater de- gree of enjoyment. Similar items were used to assess partici- pants’ feelings of enjoyment from acting on their intrinsic goal for the term: “Rate how much acting on your intrinsic goal for the term led to feelings of enjoyment”, “...feelings of pleasure”, and “...feelings of satisfaction”. The sum of these three items was used to calculate a total score for feelings of enjoyment from acting on their intrinsic goal for the term. Self-Reinforcement for Goal Progress. Participants were asked to rate separately how much the progress on their intrin- sic goals generally and on their intrinsic goal for the term led to self-reinforcement. Participants rated their responses using 8-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (none) to 8 (a great deal). The sum of three items was used to assess participants’ use of self-reinforcement for progress on their intrinsic goals in gen- eral: “Rate how much the progress on your intrinsic goals typi- cally leads to self-reinforcement”, “...self-praise”, and “…self- rewards”, with higher scores reflecting more general use of self-reinforcement. The sum of three similar items was used to assess participants’ use of self-reinforcement for progress on their intrinsic goal for the term: “Rate how much the progress on your intrinsic goal for the term led to self-reinforcement”, “...self-praise”, and “…self-rewards”. Psychological Well-Being Index. Following previous me- thods (Sheldon & Elliott, 1999; Sheldon & Kasser, 1998; Sheldon et al., 2004), a composite index of psychological well- being was created from the four measures described below. The raw scores for each participant on each of the following four measures were obtained and then transformed into z-scores. The negative affect z-score was then subtracted from the sum of the mental health, self-esteem, and positive affect z-scores to obtain an overall index for the participant with higher scores in- dicating increased well-being. The Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5; Berwick et al., 1991) was used to assess mental health. This measure was comprised of five items, three of which are aimed at depressive symptoms and well-being, while two questions measure symptoms of anxiety. Individual are asked to rate on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (all of the time) to 6 (none of the time) how often they had the various affective experiences in the last month. The total score is calculated by reversing the answers to the third and fifth items and summing up the scores. The scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater well- being. Scores less than or equal to 18 indicate severe depression (Cuijpers, Smits, Donker, ten Have, & de Graaf, 2009). Ber- wick et al. (1991) reported a Cronbach α of .82 for the MHI-5 and found that it successfully detected DSM psychological dis- orders. The Self-Esteem Scale (SES) was used to measure overall self-esteem as revised by Rosenberg, Schooler, and Schoenbach (1989). They selected 6 of the 10 items of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1979) in their study. An exam- ple of an item used in this study is: “I feel that I’m a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others”. The items are rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Negatively worded items four and six were reverse-scored. Higher scores on this measure are indicative of feelings of self-acceptance, self-respect, and generally positive self-evaluation. This 6-item version of the Rosenberg Self- Esteem Scale has been shown to have acceptable internal reli- ability (α = 0.78) in a sample of adolescents (McCreary, Slavin, & Berry, 1996) and was associated with adolescent behavioral problems and depression (Rosenberg et al., 1989). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Wat- son, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) consists of two 10-item scales measuring the two primary dimensions of mood—Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect (NA). Positive Affect reflects the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active, and alert, while Negative Affect reflects subjective distress and unpleas- ant engagement. On each of the 20 mood adjectives participants rated on a 5-point Likert scale the degree to which they gener- ally experienced that specific mood from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Watson et al. (1988) reported coeffi- cient alphas of .88 and 0.87 for the PA and NA scales respec- tively in a sample of undergraduates. Both the PA and the NA scales have been shown to be associated with depressive symp- toms (Crawford & Henry, 2004). Procedure Potential participants for the study were recruited via email and campus advertisements and invited to participate in an online study investigating motivation, goal processes, and psy- chological well-being. Those interested to participate were di- rected to a survey website in order to complete an online ques- tionnaire package. Before proceeding with the survey, potential participants were presented with an online consent form. Con- senting participants then proceeded to complete the survey. Upon completion, the participants were directed to an online debriefing form which outlined the study in greater detail and provided contact information of the researchers. Of the 186 participants who completed the online study, based on their choice, 143 (76.9%) participants received a bo- nus point towards an undergraduate course, while 25 (13.4%) received $10 in cash. The remaining 18 (9.7%) participants either did not indicate their preferred form of compensation or failed to make arrangements to receive their cash prize. Design and Dat a A n a l ysi s Data screening was conducted following the procedure out- Open Access 979  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL lined by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). As missing values were scattered randomly throughout the data matrix, the mean was used to estimate the missing item value and added to the scale prior to analysis. The data were then examined for univariate outliers using frequencies and z-scores. Scores were considered to be outliers if they had a z-score greater than +/− 3.29. As out- lined by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), univariate outliers were adjusted by reducing the value to 1 unit greater than the next highest value within the appropriate range. Linearity and nor- mality were examined by checking skewness and kurtosis val- ues. Multivariate outliers were examined using the Mahalanobis distance statistic. Finally, we checked for multicollinearity and singularity of the variables. The whole sample was sorted into two goal subsamples so that the association of different self-regulatory components with well-being could be examined under general and term intrinsic goal conditions. The processes involved were exam- ined by means of correlations and regression analyses. All re- gression analyses were run on z-scores. Regression analyses examined the general goals subsample for associations of psy- chological well-being with the following goal-related self-rat- ings: general progress on goals, general use of self-reinforce- ment for progress on goals, and general feelings of enjoyment for progress on goals. Regression analyses examined the term goals subsample for associations of well-being with the follow- ing goal-related self-ratings: progress on the term goals, self- reinforcement for progress on the term goals, and feelings of enjoyment for progress on term goals. Results In the whole sample (N = 186), preliminary tests for gender differences on all the variables found only one significant dif- ference, with males scoring higher on psychological well-being than females (M = 1.31 vs. M = −0.38, t = 3.05, p < 0.01). Due to lack of gender differences among the variables, we collapsed the data across genders for the rest of the statistical analyses. Analysis of the General Goals Subsample Table 2 presents the minimum and maximum values, means, standard deviations, and internal reliability coefficients of all of the variables for the general goals subsample. Means for all established scales, that is, the Self-Reinforcing Subscale, the MHI-5, the 6-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the PA and NA scales of the PANAS were within one standard devia- tion of those found in university samples (Mezo, 2009; Ogun- yemi & Mabekoje, 2007; Rosenberg, 1979; Watson et al., 1988). Correlation of the Variables in the General Goals Sub- sample. One-tailed Pearson correlations were conducted to examine significant associations among the variables in the general goals subsample (see Table 3). We found a number of significant positive intercorrelations among the variables. There was somewhat of a trend for the two positive experiential self-regulatory variables, autonomous regulation and enjoyment, to have higher correlations with each other and with well-being in the general goals subsample than in the term goal subsample (also see Table 4). As expected, autonomous regulation was positively correlated with well-being. Rated general goal pro- gress and the two self-reinforcement variables also showed significant positive correlations with each other and with well- being. General goal progress was not significantly correlated Table 2. Alpha reliability and descriptive statistics for all variables in the general goals subsample (N = 89). Variable α Min Max M SD 1) Goal progress - 0 8 5.291.82 2) Self-reinforcement for goal progress 0.77 14 24 17.353.81 3) Enjoyment 0.85 14 24 20.092.99 4) Global self-reinforcement 0.73 5 25 16.544.07 5) Autonomous regulation 0.78 10.67 21.0016.041.96 6) Controlled regulation 0.67 7.50 18.0013.962.42 7) Well-being index 0.82 −9.79 5.69 0.323.37 Mental health 0.80 9 29 21.034.25 Self-esteem 0.85 11 24 19.693.13 Positive affect 0.84 22 47 35.615.52 Negative affect 0.88 10 42 20.616.78 Note: Goal progress = progress on intrinsic goals in general; Enjoyment = feel- ings of enjoyment of acting on intrinsic goals in general; Self-reinforcement for goal progress = self-reinforcement for progress on intrinsic goals in general; Global self-reinforcement = Self-Reinforcing Subscale. Table 3. Bivariate correlations of all variables in the general goals subsample (N = 89). Variable 12 3 4 5 6 7 1) Goal progress -0.26** 0.36** 0.30** 0.14 −0.12 0.27* 2) Self-reinforcement for goal progress - 0.58** 0.57** 0.35** 0.04 0.32** 3) Enjoyment - 0.45** 0.47** −0.03 0.45** 4) Global self-reinforcement - 0.36** 0.13 0.20* 5) Autonomous regulation - 0.140.50** 6) Controlled regulation - −0.38** 7) Well-being - Note: Goal progress = progress on intrinsic goals in general; Enjoyment = feel- ings of enjoyment of acting on intrinsic goals in general; Self-reinforcement for goal progress = self-reinforcement for progress on intrinsic goals in general; Global self-reinforcement = Self-Reinforcing Subscale. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. Table 4. Bivariate correlations of all variables in the term goals subsample (N = 93). Variable 12 3 4 5 67 1) Goal progress -0.48** 0.57** 0.38** 0.36**0.070.42** 2) Self-reinforcement for goal progress - 0.60** 0.57** 0.21*0.000.36** 3) Enjoyment - 0.30** 0.27** 0.07 0.29** 4) Global self-reinforcement - 0.32** 0.140.24** 5) Autonomous regulation - 0.28** 0.43** 6) Controlled regulation - −0.37** 7) Well-being - Note: Goal progress = progress on intrinsic term goals; Enjoyment = feelings of enjoyment of acting on intrinsic term goals; Self-reinforcement for goal progress = self-reinforcement for progress on intrinsic term goals; Global self- reinforce- ment = Self-Reinforcing Subscale. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. with autonomous regulation or controlled regulation. Con- trolled regulation did not correlate significantly with most other variables, including autonomous regulation. It was negatively Open Access 980  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL correlated with well-being. Overall, the correlations of the cy- bernetic, behavioral, and experiential goal-related ratings with the global variables supported their construct validity. Regression Analysis of the General Goal-Related Self- Regulatory Components. A regression analysis was used to test the association of psychological well-being with the three general goal-related self-regulatory components in the general goals subsample (N = 89). Ratings of cybernetic, behavioral, and experiential self-regulatory components related to the pur- suit of goals in general were entered together into the regression to determine their unique contributions to psychological well- being. Only general enjoyment was found to have a significant beta (β = 0.36, p < 0.01), while general goal progress (β = 0.12, p > 0.20) and general self-reinforcement for goal progress were not significantly associated with well-being (β = 0.07, p > 0.50) in the overall regression equation [R2 = 0.216, F(3, 85) = 7.80, p < 0.001]. Analysis of the Term Goals Subsample Table 5 presents the minimum and maximum values, means, standard deviations, and internal reliability coefficients of all of the variables for the term goals subsample. As in the general goals subsample, the means for all established scales were within one standard deviation of those found in university sam- ples (Mezo, 2009; Ogunyemi & Mabekoje, 2007; Rosenberg, 1979; Watson et al., 1988). The ratings of feelings of enjoy- ment in the term goal subsample, however, were considerably lower than those in the general goals subsample (also see Table 2). There were no other apparent differences between the gen- eral and term goals subsamples. Correlation of the Variables in the Term Goals Subsam- ple. One-tailed Pearson correlations were conducted to examine significant associations among the variables in the term goals subsample (see Table 4). The pattern of significant correlations was similar to that found in the general goals subsample, but with a few exceptions. Again there were a number of signifi- cant positive intercorrelations among the variables. There was somewhat of a trend, however, for the behavioral and cyber- netic regulation variables, including rated term goal progress, to Table 5. Alpha reliability and descriptive statistics for all variables in the term goals subsample (N = 93). Variable α Min Max M SD 1) Goal progress - 1 8 5.521.86 2) Self-reinforcement for goal progress0.79 3 24 16.894.14 3) Enjoyment 0.92 8 24 16.893.90 4) Global self-reinforcement 0.79 4 25 15.514.36 5) Autonomous regulation 0.79 10.33 21.00 15.852.04 6) Controlled regulation 0.66 7.00 18.50 13.682.35 7) Well-being index 0.80 −9.59 6.43 0.263.38 Mental health 0.80 9 30 20.894.31 Self-esteem 0.85 12 24 19.733.10 Positive affect 0.85 21 47 35.045.83 Negative affect 0.89 10 42 20.417.05 Note: Goal progress = progress on intrinsic term goals; Enjoyment = feelings of enjoyment of acting on intrinsic term goals; Self-reinforcement for goal progress = self-reinforcement for progress on intrinsic term goals; Global self-reinforce- ment = Self-Reinforcing Subscale. have higher correlations with each other and with well-being than in the general goals subsample. Term goal progress was also significantly correlated with autonomous regulation. Con- trolled regulation was negatively correlated with well-being, not correlated with goal progress, and positively correlated with autonomous regulation. With regard to the latter finding, par- ticipants appear to have accessed some similar processes in these two forms of experiential self-regulation under short-term goal conditions. For the most part, the correlations of the cy- bernetic, behavioral, and experiential goal-related ratings with the global variables supported their construct validity. Regression Analysis of the Term Goal-Related Self-Re- gulatory Components. A regression analysis was used to test the association of psychological well-being with the three term goal-related self-regulatory components in the short-term goals subsample (N = 93). Ratings of cybernetic, behavioral, and experiential self-regulatory components related to the pursuit of short-term goals were entered together into the regression to determine their unique contributions to psychological well- being. Term goal progress was found to be significant (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), term self-reinforcement was marginally significant (β = 0.22, p < 0.08), while term enjoyment was not significantly associated with well-being (β = −0.02, p > 0.80) in the overall regression equation [R2 = 0.210, F(3, 89) = 7.87, p < 0.001]. Discussion The present study examined whether psychological well-be- ing was associated with compatibilities between self-regulatory components and goal conditions. Consistent with construal- level theory, our findings indicated that enjoyment of the activ- ity, an experiential self-regulatory component, accounted for psychological well-being in the pursuit of goals more generally. In contrast, in the pursuit of short-term goals, cybernetic and behavioral components in self-regulation, namely perception of goal progress and self-reinforcement for goal progress, ac- counted for well-being. The latter are notable findings given the fact that they occurred even in the pursuit of intrinsic goals, when one would expect extrinsic goals to be more consistent with the situational focus of cybernetic and behavioral regula- tion. These results suggest, therefore, that cognitive and behav- ioral self-regulations are generally applicable to managing vari- ous types of goals in specific situations. Overall, the two global experiential regulatory variables were more strongly associated with well-being than was global self- reinforcement. Consistent with past research, controlled regula- tion was negatively associated with well-being (Barbeau et al., 2009; Koestner et al., 2008; Sheldon et al., 2004). These effects are likely to be due to the positive and negative contributions of autonomous and controlled regulations, respectively, to the satisfaction of basic needs (Deci & Ryan, 1987; Ryan & Deci, 2000) and their relations to feelings of security and confidence (Ratelle et al., 2004). Controlled regulation had no associations with other benign processes, suggesting that it might contain various dysfunctional elements. The absence of significant correlations with enjoyment and positive reinforcement sug- gests that it is also likely to involve a mix of both pleasant as well as unpleasant experiences. Unlike autonomous regulation, controlled regulation appears to lack attributes which lead to enjoyment of activities and approach behaviors. These factors likely undermine its effectiveness to promote long-term satis- faction and well-being. Open Access 981  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL Well-being has been shown to be the product of effective coping, as proposed by cognitive-behavioral and cybernetic theories (Bandura, 1997; Carver & Scheier, 1998, Kanfer, 1970). Individuals find cognitive and behavioral interventions helpful to cope with a variety of psychological problems (Feb- braro & Clum, 1998). Our findings also suggest that such self- regulatory processes are related to health benefits. The contri- butions of cognitive and behavioural self-regulatory processes to well-being have also been recognized in the motivational literature (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999; Sheldon & Kasser, 1995, 1998). Sheldon and Kasser (1995) also suggest, however, that psychological health not only depends on how we achieve our goals but also why we seek them. While the cybernetic and behavioural self-regulations focus more on how to cope with specific tasks and situations, experiential self-regulations focus more on why we pursue goals. Our findings support but also extend such previous theorizing in showing that these various aspects of self-regulation are related. Autonomous regulation, a global experiential variable, and global self-reinforcement, a behavioral variable, were correlated with each other and with other self-regulatory processes. These findings and those of others suggest that experiential and behavioral self-regulatory processes are likely to be complementary to each other. For example, in studies of experiential self-regulation, implementa- tion planning was found to play a pivotal role in making pro- gress on short-term goals, which in turn, promoted psychology- cal well-being (Koestner et al., 2008; Sheldon & Elliot, 1999; Sheldon & Kasser, 1998). As another example, motives have been shown to promote exercise participation through influ- encing behavioral and experiential self-regulation (Ingledew & Markland, 2008). Our findings also suggest the need for more comprehensive or encompassing theories of self-regulation to account for psy- chological well-being. Also pointing in this direction are the findings from positive psychology that a number of life active- ties contribute to life satisfaction, including the pursuit of plea- sure, engagement in activities, and finding meaning (Peterson, Park, & Seligman, 2005). The question arises as to how all these constructs might be related to each other with regard to the promotion of life satisfaction and well-being? Our findings suggest that experiences and activities that enhance well-being share similarities in their activation of pleasant experiences but might also have unique compatibilities with our internal and external environments which also have to be taken into consid- eration. Along this line of inquiry, future research could exam- ine the differential contributions of other types of self-regula- tion to well-being, such as emotional regulation, under different types of goal conditions. Study Limitations One aspect of our study was that the imbalance in the sex ra- tio might limit the generalizability of our findings to the general population. However, most of our measures did not reveal any significant differences between males and females. Another limitation of our study was that we examined self-regulatory processes only under intrinsic goal conditions. Consequently, one might argue that the reason we did not find that enjoyment was associated with well-being in the short-term goals subsam- ple was because we had restricted the range of the enjoyment variable. However, this possibility can be ruled out because the SD of the enjoyment variable in the term goals subsample was actually larger than in the general goals subsample. Conclusion In conclusion, our results were consistent with predictions from construal-level theory that compatibilities between self- regulatory processes and goal conditions would be related to psychological well-being. It makes sense to find that the impact of different self-regulations would be related to their similari- ties to the contents and conditions of our internal and external environments. Although each type of self-regulation appears to have its own niche, our study also indicated considerable asso- ciations among them through sharing pleasant experiences. This finding suggests that they are related building blocks in the overall management of well-being. Our study helps to ex- tend theoretical conceptualizations of well-being by integrating cy- bernetic, behavioral, and experiential self-regulatory proc- esses and types of goal pursuits found in the promotion of well-being. Our study points toward the need to further develop compre- hensive psychological theories that can more fully ac- count for the various ways we acquire well-being and pursue life satis- faction. We hope that our findings and proposals have been a step toward this important goal. Acknowledgement This study was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Master’s Award held by the second author. REFERENCES Ahrens, A. H. (1987). Theories of depression: The role of goals and the self-evaluation process. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11, 665- 680. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01176004 Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman. Barbeau, A., Sweet, S., & Fortier, M. (2009). A path-analytic model of self-determination theory in a physical activity context. Journal of Applied Biobehavioural Research, 14, 103-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9861.2009.00043.x Berwick, D. M., Murphy, J. M., Goldman, P. A., Ware, J. E., Barsky, A. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (1991). Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care, 29, 169-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008 Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the self-regulation of be- havior. New York: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174794 Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement proper- ties, and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Jour- nal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 245-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/0144665031752934 Crocker, J., Brook, A. T., Niiya, Y., & Villacorta, M. (2006). The pur- suit of self-esteem: Contingencies of self-worth and self-regulation. Journal of Personalit y, 74, 1749-1771. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00427.x Cuijpers, P., Smits, N., Donker, T., ten Have, M., & de Graaf, R. (2009). Screening for mood and anxiety disorders with the five-item, the three-item, and the two-item Mental Health Inventory. Psychiatry Research, 168, 250-255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.012 Deci, E. L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B. C., & Leone, D. R. (1994). Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality, 62, 119-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00797.x Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-deter- mination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press. Open Access 982  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7 Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1024-1037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024 Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1995). Human autonomy: The basis for true self-esteem. In M. H. Kernis (Ed.), Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem (pp. 31-49). New York: Plenum Press. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psy- chological Inquiry, 11, 227-268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 Endler, N. S., & Kocovski, N. L. (2000). Self-regulation and distress in clinical psychology. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 569-599). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50046-9 Febbraro, G. A. R., & Clum, G. A. (1998). Meta-analytic investigation of the effectiveness of self-regulatory components in the treatment of adult problem behaviors. Clinical Psychology Review, 18, 143-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00008-1 Guay, F., Mageau, G. A., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). On the hierarchical structure of self-determined motivation: A test of top-down and bot- tom-up effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 992- 1004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167203253297 Hyland, M. (1987). Control theory interpretation of psychological me- chanisms of depression: Comparison and integration of several theo- ries. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 109-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.102.1.109 Ingledew, D. K., & Markland, D. (2008). The role of motives in exer- cise participation. Psychology and Health, 23, 807-828. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870440701405704 Kanfer, F. H. (1970). Self-regulation: Research, issues, and specula- tions. In C. Neuringer, & J. L. Michael, (Eds.), Behavior modifica- tion in clinical psychology (pp. 178-220). New York: Appleton-Cen- tury-Crofts. Kocovski, N. L., & Endler, N. S. (2000). Self-regulation: Social anxiety and depression. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 5, 80-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9861.2000.tb00065.x Koestner, R., Otis, N., Powers, T. A., Pelletier, L., & Gagnon, H. (2008). Autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and goal progress. Journal of Personality, 76, 1201-1229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00519.x Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (1998). The role of feasibility and desirabil- ity considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of tem- poral construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 5-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.5 Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Ame- rican Psychologist, 57, 705-717. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705 McCreary, M. L., Slavin, L. A., & Berrry, E. J. (1996). Predicting problem behavior and self-esteem among African American adoles- cents. Journal of Adole sc ent s Research, 11, 216-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0743554896112004 Mezo, P. G. (2009). The Self-Control and Self-Management Scale (SCMS): Development of an adaptive self-regulatory coping skills instrument. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 83-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10862-008-9104-2 Ogunyemi, A., & Mabekoje, S. (2007). Self-efficacy, risk-taking be- havior and mental health as predictors of personal growth initiative among university undergraduates. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 5 , 349-362. Owens, T. J., Mortimer, J. T., & Finch, M. D. (1996). Self-determina- tion as a source of self-esteem in adolescence. Social Forces, 74, 1377-1404. Pelletier, L. G., Sharp, E., Levesque, C., Vallerand, R. J., Guay, F., & Blanchard, C. (2007). The General Motivation Scale (GMS): Its Va- lidity and Usefulness in Predicting Success and Failure at Self-Re- gulation. Manuscript in preparation. Ottawa: University of Ottawa. Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientation to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z Powers, T. A., Koestner, R., Lacaille, N., Kwan, L., & Zuroff, D. C. (2009). Self-criticism, motivation, and goal progress of athletes and musicians: A prospective study. Personality and Individual Differ- ences, 47, 279-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.03.012 Ratelle, C. F., Vallerand, R. J., Chantal, Y., & Provencher, P. (2004). Cognitive adaptation and mental health: A motivational analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 459-476. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.208 Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books. Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., & Schoenbach, C. (1989). Self-esteem and adolescent problems: Modeling reciprocal effects. American So- ciological Review, 54, 1004-1018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2095720 Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-be- ing. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living well: A self-deter- mination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 139-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9023-4 Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social P s y chology, 76, 482-497. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482 Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (1995). Coherence and congruence: Two aspects of personality integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 531-543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.531 Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (1998). Pursuing personal goals: Skills enable progress, but not all progress is beneficial. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 1319-1331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/01461672982412006 Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Kasser, T. (2004). The independent effects of goal contents and motives on well-being: It’s both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 475-486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167203261883 Siegert, R. J., McPherson, K. M., & Taylor, W. L. (2004). Toward a cog- nitive-affective model of goal-setting in rehabilitation: Is self-regula- tion theory a key step? Disability and Rehabilitation, 2 6, 1175-1183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001724834 Spangler, W. D. (1992). Validity of questionnaire and TAT measures of need for achievement: Two meta-analyses. Psychological B ulletin, 112, 140-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.140 Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). New York: Allyn & Bacon. Thrash, T. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Implicit and self-attributed achieve- ment motives: Concordance and predictive validity. Journal of Person - ality, 70, 729-755. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.05022 Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psycholo- gical distance. Psychological Review, 117, 440-463. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018963 Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Wakslak, C. (2007). Construal levels and psy- chological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. Journal of Consumer Ps ycho logy, 17, 83-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70013-X Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and vali- dation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Jour n a l of Personality and Social P sychology, 54, 1063-1070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 Open Access 983  P. HORVATH, V. MCCOLL Open Access 984 Wicker, F. W., Hamman, D., Reed, J. H., McCann, E. J., & Turner, J. E. (2005). Goal orientation, goal difficulty, and incentive values of aca- demic goals. Psychological Reports, 96, 681-689. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.96.3.681-689 Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2001). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives (2n d ed.). Mah- wah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

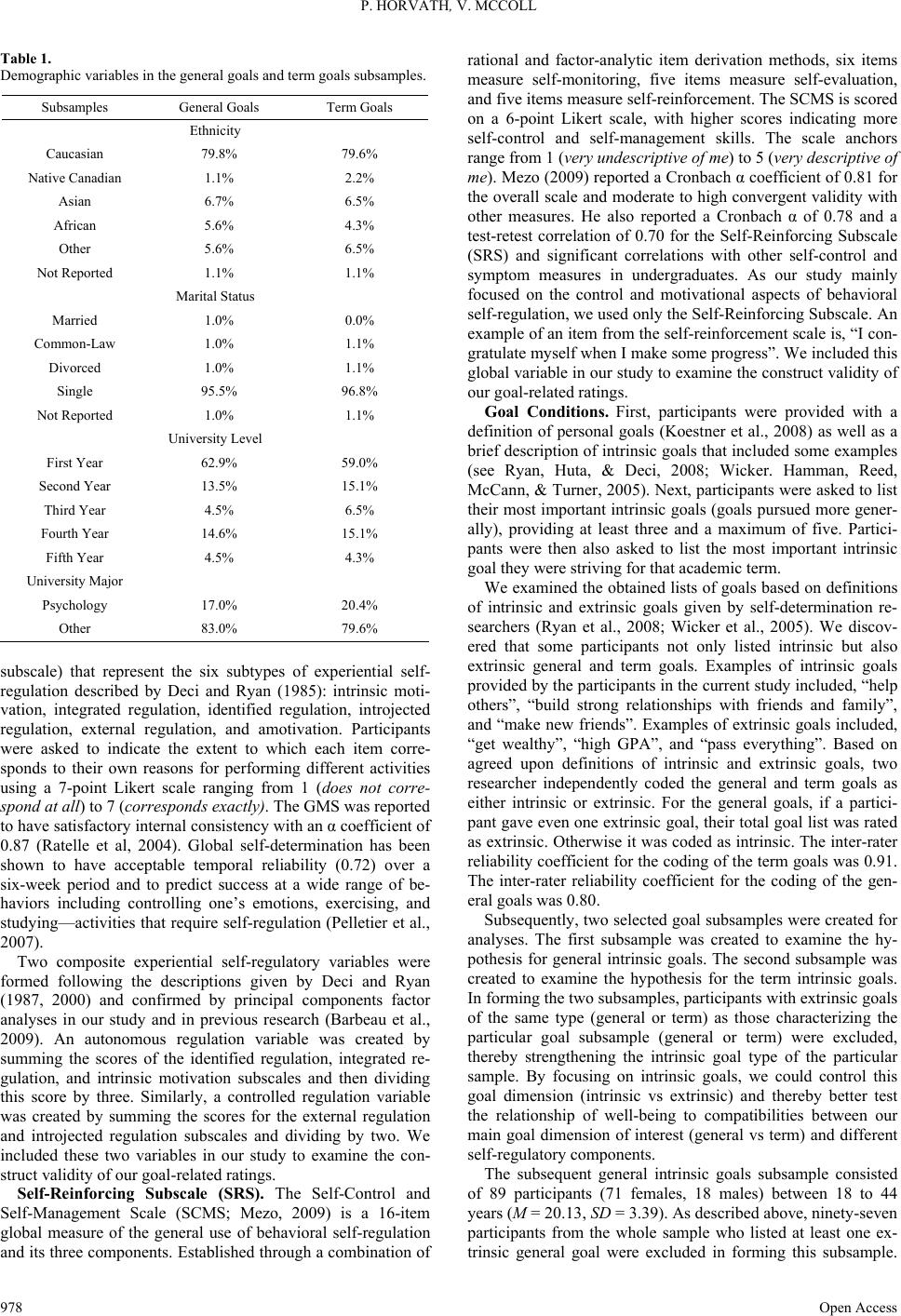

|