Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 2013, 3, 319-327 Published Online December 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojvm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojvm.2013.38052 Open Access OJVM Computer Assisted Learning for Improving Cattle Palpation Skills of Veterinary Students Scott T. Norman1, Gloria Dall’Alba2 1School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences and E.H. Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, Australia 2School of Education, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia Email: snorman@csu.edu.au Received October 21, 2013; revised November 21, 2013; accepted November 28, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Scott T. Norman, Gloria Dall’Alba. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Scott T. Norman, Gloria Dall’Alba. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. ABSTRACT This study investigated the effect of a computer assisted learning (CAL) tool on the development of skills in palpation of the reproductive tract of the cow per rectum (rectal palpation) by fourth-year students in a Bachelor of Veterinary Science (BVSc) degree program. A secondary aim was to determine if animal welfare could be improved by the CAL intervention. The CAL tool was developed to provide: vivid, three-dimensional interactive graphics of the relevant anatomy and skills; a comprehensive g lossary of terminology used in association with the skills; and formative assess- ment tasks. Prior to its introduction to the course, industry stakeholders assessed the CAL tool graphics as an accurate depiction of the procedures. Two consecutive cohorts of students were surveyed prior to (n = 91) and after the CAL intervention (n = 111). Responses to student surveys suggested that post-intervention skills were learned at approxi- mately the same rate as pre-intervention. However, tutor surveys indicated that students in the pre-intervention group may have had insufficient understanding for accurate self-assessment compared to post-intervention students. Accord- ing to tutors, substan tially more studen ts in the post-intervention group gained practical sk ills at an improved rate and to a higher level of competency. Both student and tutor surveys indicated that there was a minimal discomfort to animals in these practical classes. From an animal welfare point-of-view, it was concluded that the interv ention would not result in a reduction in the number of animals required during practical sessions. However, due to the preparation and rein- forcement provided by the CAL tool, animals were u sed more efficiently by students after the intervention, resulting in the attainment of a higher level of skill. Knowledge gained fro m this study may be relevant to other disciplin es requir- ing students to develop practical skills associated with animals or humans. Keywords: Computer Assisted Learning (CAL); Computer Simulation; Veterinary Science Education ; Skill Attainmen t; Professi ona l Educati o n 1. Introduction While there are many examples of computer assisted learning (CAL) packages being incorporated into higher education programs, many of the early attempts simply provided information in an interesting, text-based pres- entation [1]. However, with improved technology, the potential to produce powerful simulations is coming within the financial reach of mainstream teaching [2]. These newer technologies have the potential to promote students to learn in ways that extend conventional teach- ing and learning methods. In order to achieve this poten- tial, their design and use must be pedagogically sound and appropriate for the task, course and educational pro- gram to which they contribute [3-5 ]. Their potential con- tribution will be undermined if they simply perpetuate ineffective teaching and learning methods, as many early attempts to utilise new technologies have done, due to limited understanding of higher education pedagogy [4,6,7]. If used thoughtfully and appropriately, these newer technologies can contribute to preparing higher education students for the world of work in authentic ways, particularly within some professions [3,8,9]. The nature of a veterinarian’s work means that pre- paring students for this profession includes developing  S. T. NORMAN, G. DALL’ALBA 320 the necessary competence in a manner that takes account of animal welfare. For example, competence in the tactile evaluation of a live animal’s abdominal body parts via trans-rectal palpation (rectal palpation) is essential if re- productive efficiency is to be maximised, disease is to be accurately identified and animal suffering minimised. This is particularly so for veterinarians involved in cattle practice [10]. Currently, veterinary students are usually taught rectal palpation skills in cattle by using abattoir specimens and practising on live animals. Although this method of teaching has important similarities to veterinary practice, it has the following drawbacks: 1) There is a risk of damage to the rectum in live ani- mals, and cow health is put at risk when inexperienced palpators are learning. Rectal tears can result in severe illness or death of the animal. 2) The risk of damage to the rectum is increased when more than one person palpates a cow as is necessary during practical classes. 3) Prolonged palpation of individual cows often leads to rectal straining by the cow. This increases the diffi- culty for an inexperienced operator to palpate the struc- tures. A consequence is that the procedure can become frustrating for the student and may result in loss of inter- est in learning, or a feeling of inadequacy. 4) A large number of animals have to be palpated be- fore competency can be achieved. The Australian Cattle Veterinarians, a special interest group of the Australian Veterinary Association, currently recommends that a minimum of 2000 cows should be palpated before an individual is con sidered eligible to take th eir competency examination [10]. 5) Providing abatto ir specimens for practical classes is time consuming and can be influenced by the season due to seasonal breeding practices on many properties. 6) There is a risk of zoonotic disease (e.g. Q-fever and brucellosis) when abattoir specimens are utilised for teaching. 7) The anatomical relationships of the organs to be as- sessed are lost when abattoir specimens are used. As a consequence, students don’t have the opportunity to gain a good spatial understanding of the anatomy of the ab- domen of the cow prior to palpation. 8) Students can only practise their skills during set practical classes when specimens and cows are available. There is very limited potential to revise material or gain further experience in their time. 9) Providing this type of training is expensive and re- quires high levels of input from tutors, lecturers and clinical staff. One of the perceived methods for overcoming some of these difficulties is the use of CAL tools. In human medical education, the successful incorporation of CAL has been described in fields such as neonatology [11] and cardiology [12]. In veterinary education, the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Glasgow has made advances in the incorporation of technology into the teaching of veterinary science [13]. One notable ex- ample is the computer-aided learning system described as CLIVE® (Computer Learning Initiative in Veterinary Education). Using CLIVE, computer simulations have replaced a number of practicals which previously would have required the use of live animals. In addition to im- proving animal welfare conditions, the use of these pro- grams has reduced the costs associated with the practical classes and the time involved in organising practicals requiring the use of live animals. This has increased the amount of time that lecturers can spend supporting small group and independent learning [13]. While physical simulators have been developed to assist with the teach- ing of rectal palpation, they are still relatively expensive and do not address the need for student access to learning material at times other than scheduled in the timetable. Using a computer simulation for learning rectal palpa- tion in cattle could allow unskilled and inexperienced students to become familiar with rectal examinations without causing pain or suffering to a live animal. When students progress to practise on live animals, they would have some prior knowledge and experience on the simu- lator and be less likely to make mistakes that may result in distress or pain to the animal. This approach has the potential to improve students’ rectal palpation skills in a way that includes relevant animal welfare issues. In addi- tion, having access to a realistic representation of the internal structures of the abdomen of the cow would al- low revision to occur at the students’ leisure regardless of the availability of liv e animals. The incorporation of sophisticated virtual tactile sen- sations into a rectal palpation simulator is currently out- side the budget of most edu catio n al institu tion s. Howev er, the use of three-dimensional animations allows the users to gain an accurate visualisation of the position of the arm within the animal during the examination and to see the correct procedure for efficient manipulation. Users can also see the position of the relevant organs from a variety of perspectives and visualise the anatomical rela- tionship of organs with other abdominal structures and the examiner’s hand. This paper explores the use of a CAL tool in teaching practical skills to veterinary students in authentic ways. The use of the CAL tool was authentic in the sense that it closely related to tasks required of practicing veterinari- ans. It sought to exploit the opportunities provided by CAL in a way that was relevant to veterinary science students and supported their learning. In particular, the effectiveness of the tool is assessed for its role in the students’ learning of specific practical skills that are es- Open Access OJVM  S. T. NORMAN, G. DALL’ALBA 321 sential to veterinary practice, while also addressing is- sues of animal welfare. The aims of this study were to investigate whether the CAL tool could be us e d: 1) To improve students’ three-dimensional perceptions of the anatomical relationship of structures in the abdo- men of the cow. 2) To teach the skills, or parts of the skills, of rectal palpation in cattle. 3) To assess student perceptions of their safety during the procedure and to address perceived animal welfare issues involving the use of live animals in the teaching of these skills. 2. Method 2.1. Setting and Study Participants The setting for the study was within a course on Veteri- nary Reproduction taught in the fourth year of the Bachelor of Veterinary Science degree program. In the first year of the study, 91 fourth year veterinary science students were enrolled, while in the second year, there were 111 students. In this course, veterinary students have their first formal instruction in the procedure re- quired for rectal palpation of the reproductive tract in the cow, with two lectures explaining the procedure and animal welfare considerations followed by five practicals specifically devoted to learning the technique. At the completion of the practical classes, tutors run a formative practical examination in order to give students feedback on their progress. Cows were individually presented for palpation in stanchions with kick-gates secured behind and heads unrestrained. In each year of the study, 120 cows were available for use in the practical sessions. In the year prior to the CAL intervention, data were obtained on students’ mastery of th e skill of rectal palpa- tion when conventional teaching methods were used. In particular, their ability to visualise the spatial relation- ships of the organs in the cow abdomen was of interest. This assessment was achieved by surveying and observ- ing students at each practical session. Indirect indicators such as the number of practicals required to achieve competencies were also determined, as assessed by tutor and student survey. In addition, the number of cows re- quired to gain set competencies was assessed, informa- tion was gained on trauma to the cows’ rectum, and tu- tors were surveyed about students’ skill progression and cow responses to palpation. Animal care and ethics ap- proval for this study was granted by UQAEC, number SVS/739/04/T. 2.2. Design of the Computer Assisted Learning Intervention In the second year of the study, the CAL intervention was implemented with 111 students enrolled. It was not intended to replace the use of live animals, but to com- plement conventional teaching methods. The CAL inter- vention consisted of four distinct components. These components were: a three-dimensional animation that allowed students to visu alise the internal structu res of the cow abdomen from several perspectives; a three-dimen- sional animation of the procedure necessary to complete a comprehensive rectal examination of the cows’ repro- ductive tract; a comprehensive glossary of terms associ- ated with cow reproduction and palpation; and formative quizzes specifically targeted at the palpation procedure and its purpose. A screen grab of the three-dimensional animation is shown in Figure 1. Prior to implementation, key members of the veteri- nary profession assessed the CAL material to ensure it accurately depicted the movements required to complete the palpation procedure. This assessment contributed to its authenticity and was performed by representatives from a university teaching clinic, practitioner members of the Australian Cattle Veterinarians and the Queen- sland Department of Employment, Economic Develop- ment and Innovation. Student access to the CAL material was provided through the web-based platform, Blackboard®. Students were familiar with using this platform from previous courses. For the purposes of this study, this access method was beneficial in that it provided a means of quantifying how many times students accessed the mate- rial. This would have been difficult to achieve with other forms of delivery such as a CD. Students using the CAL material in the second year of the study were informed that their progress was being monitored to assess teach- ing methods. The CAL material was introduced as a rou- tine component of the curriculum. 2.3. Survey Methods In both years of the study, the same student survey was used to monitor the d evelop ment of rectal palpation skills over the duration of the practicals. Students were asked to fill in a short survey at the completion of each of the five practical classes. Students were asked to label each survey with either their student number, or use a pseu- donym if they wished to protect their privacy. A Likert scale was used in the survey for ease of analysis. Initial statements addressed student perceptions of the degree of difficulty in understanding and performing a task (e.g., I feel frustrated that I can’t do the procedures I am meant to perform). Additional statements targeted their per- ceived ability to actually perform the task (e.g., I achieved this today and more than once previously). A subsequent statement assessed the student perceptions of cow discomfort. Student responses to these statements allowed investigations that were necessary for the study, as well as potentially having a pedagogical function in Open Access OJVM  S. T. NORMAN, G. DALL’ALBA Open Access OJVM 322 Figure 1. Screen grab of the three-dimensional animation of the relevant anatomy, with menu options for the glossary and formative quizzes at the bottom of the frame. drawing their attention to central features of an aspect of veterinary practice. There were three tutors during each semester of teach- ing. Two of the tutors taught in both the pre- and post- intervention semesters. Surveys about the students’ per- formance of rectal palpation skills and cow welfare were provided to tu tors within two weeks of completion of the practicals. At the commencement of the practical ses- sions, tutors were forewarned that their feedback on stu- dent performances would be solicited at the completion of the practicals. As an additional source of data, nine stud ents from the pre-intervention year of the study were shown the CAL material in their fifth year of the veterinary science pro- gram and their comments obtained in a focus group in- terview. The comments of these students were consid- ered valuable as they were in the position of having been initially taught without the intervention and then having subsequent exposure to it. 2.4. Data Analysis Pre- and post-intervention Likert scale data were aver- aged and plotted graphically. Results from these two years were compared to determine if there were any changes in the uptake of skills and whether there were any changes to indicators of cow stress or trauma. Com- ments from the tutors and the student focus group were considered in relation to the Likert scale data. 3. Results 3.1. Pre-Intervention Results The results of student surveys on the progression of pal- pation skills prior to the CAL intervention are shown in Figure 2. On the Competency scale on the Y-axis, a score above three indicates that students report they have achieved basic competency in the skill. From this analy- sis it is apparent that students considered they rapidly mastered the skill of cervical palpation (Palpate Cervix). However, a number of the skills, including the ability to retract the uterus, are not being sufficiently mastered in the allotted time for the cou rse. Retraction of the uterus is considered essential for veterinarians involved in cattle practice, yet only 69% of the class claimed to have suc- cessfully completed this procedure more than once over the duration of the practical classes. Based on the student survey, the students’ level of frustration regarding their ability to feel the structures of the abdomen of the cow progressively decreased over the duration of the five practical classes. On a five-point scale (where 1 = high-level frustration and 5 = no frustra- tion), student responses initially indicated feelings of mild frustration (score 3/5) that they couldn’t feel the structures, to becoming somewhat less frustrated (score 3.7/5) during the final practical regarding what they were expected to achieve. Overall, the score increased by a mean of 0.7 po i nts. With regard to the ability of students to visualise the internal structures of the abdomen of the cow, the mean score (1 = high difficulty in visualising and 5 = easily visualising) progressively increased from 3.5 to 4.2 over the duration of the 5 practical classes. This suggests the students progressed from having moderate confidence in their ability to visualise the internal structures of the ab- domen, to being relatively confident they could visualise the structures and the procedures they were supposed to  S. T. NORMAN, G. DALL’ALBA 323 Figure 2. The uptake of rectal palpation skills in the pre-intervention cohort. A competency of 1 indicates the student is un- able to perform the task, 2 indicates the task was successfully completed for the first time, 3 indicates the task has been com- pleted on several occasions and that in the context of this study, the competency has been achieved. From left to right, the five columns for each procedure represent consecutive practical sessions (1 to 5). CL: Corpus Luteum; UA: Uterine Artery. perform. In all practical sessions in the first year of the study, the mean score for whether students felt at risk of injury from the cattle or facilities was approximately 4.7 (1 = felt at risk and 5 = felt very safe). With regard to per- ceived risk, all students either disagreed or strongly dis- agreed that they felt at risk of injury from the cattle or facilities when palpating cattle in the Veterinary School facilities. With regard to performing the task, 69% of the stu- dents felt they had completed uterine retraction on more than one occasion by the end of the practical sessions. However, student confidence in their ability to perform the palpation procedures increased only marginally from 3.3 to 3.5 over the duration of the classes. This marginal improvement was in agreement with tutor comments suggesting that only 25% of the class were at an accept- able level of competency by the completion of the prac- tical sessions. Survey scores based on cow movement and vocalisa- tion were ranked from 1 (indicating the cow standing quietly and calmly) to 5 (indicating the cow moving and bellowing constantly). Du ring this practical series, scores ranged from 1.3 at the commencement of the practical classes to 1.5 during the last class. This suggested that, in general, the cows stood quietly, with intermittent in- stances where they moved just enough to make palpation awkward for the stud ent. Trauma and perceived stress to cows in the pre-inter- vention practicals was minimal based on both student and tutor survey. This was consistent with observations by the first author. The amount of blood on the glove post palpation per student per practical session ranged from none, to one instance with a smear of blood. Based on tutor comments, two cows had to be withdrawn from the practical classes as a result of moderate to severe rectal irritation. This is a low occurrence of injury to the cows considering that approximately 1800 instances of rectal palpation occurred over the duration of the five practical classes. One tutor who had been associated with the course for approx imately 10 years suggested that this was a relatively normal number. Results from the tutor survey suggested that the average cow can be palpated by three students before it needs to be replaced due to rectal irritation as manifest by blood smearing on the palpator’ s sleeve, or excessive straining ma k i n g p alpation di f ficult. Taking into account survey results and tutor comments, each student needed to palpate at least four cows per class in order to reach the level of competence achieved. This translated into approximately 20 instances of rectal palpation per student over th e duration of the five practi- cal classes. From these figures, it was calculated that for the five pre-intervention palpation classes, a total of ap- proximately 1.3 cows/student were required in order to Open Access OJVM  S. T. NORMAN, G. DALL’ALBA 324 achieve this level of competency. 3.2. Post-Intervention Results In the following year, when the CAL intervention was introduced, analysis of online access data indicated that students accessed the CAL resource an average of 20 times each over the period of the study from mid-March to mid-June, with a range of 0 to 137 times. This is equivalent to each student accessing the material a mean of 1.7 times/week. There were 15 of the 111 students (13.5%) who did not directly access the material, al- though they may have observed it with others. Results of student surveys on the pr ogression of palp a- tion skills after the CAL intervention are shown in Fig- ure 3. As in the pre-intervention cohort, students rapidly mastered the skill of cervical p alpation. Based on student surveys, the uptake of the other twelve skills was ap- proximately the same, or marginally less than for the equivalent period in the pre-intervention cohort. Notably, for retraction of the uterus, which is an essential skill, a mean level of acceptable competency was only just achieved at the completion of the practicals, but a final level was reached that was marginally higher than in the pre-intervention group. Based on the student survey, the post-intervention students’ level of frustration reg arding their ability to feel the structures of the abdomen of the cow was initially less than for the pre-intervention group and reduced fur- ther over the duration of the five practical sessions. Stu- dents progressed from initially feeling relatively relaxed (score 3.5/5) that they could feel the structures, to be- coming more confident (score 3.9/5) during the final practical regarding their ability to understand what they were expected to achieve. With regard to the ability o f post-intervention studen ts to visualise the internal structures of the cow abdomen, the mean score increased from 3.9 to 4.5 over the five practical sessions, compared with 3.5 to 4.2 in the pre- intervention year. The higher scores are consistent with tutor comments that post-intervention students had a clearer understanding of the abdominal structures and higher level skills such as uterine retraction. One tutor made the comment that there was a lot less confusion with regard to what they were supposed to be palpating compared to the pre-intervention year. It was also sug- gested by this and another tutor that this cohort of stu- dents may have judged themselves harder in the self as- sessment survey (Figure 3) compared to the pre-inter- vention year, as it was apparent they clearly knew what they were meant to do. Thus, some individuals in the pre- intervention cohort may have felt they had achieved the required result and recorded it as a success despite falling short of the skill requirement, while students in the post- intervention year were less likely to incorrectly record a skill as successfully achieved. In all practical sessions in the second year of the study, the mean score for whether students felt at risk of injury from the cattle or facilities was approximately 4.7/5. With regard to perceived risk, all students either dis- agreed, or strongly disagreed that they felt at risk of in- jury from the cattle or facilities when palpating cattle in the Veterinary School facilities. This result was the same as the previous year. With regard to performing the task, 80% of students (compared to 69% pre-intervention) reported they had completed uterine retraction on more than one occasion by the completion of the practical sessions. After the intervention, student confidence in their ability to per- form the palpation procedures started at a higher level than in the pre-interv ention year (3.7/5 compared to 3.3), and increased to a higher level (4.4/5 compared to 3.5). This suggests they had a clearer understanding of what they were meant to do compared to the pre-intervention group. Tutor assessments reflected student assessments of their ability to complete the retraction procedure. After students completed the formative assessment, one tutor with ten years experience of teaching rectal palpation noted that 81% (90 out of 111) of the class were at an acceptable level of competency at completion of the five practical sessions. This compares favourably with 25% the previous year. During this post-intervention practical series, survey scores based on cow movement and vocalisation ranged from 1.3 at the commencement of the practical classes to 1.4 during the final practical. This suggested that, in general, the cows stood quietly, with intermittent in- stances where they moved just enough to make palpation awkward for the student. Trauma and perceived stress to cows in the post-intervention practicals was minimal based on both student and tutor survey. This was similar to the pre-intervention finding. Over the five practical sessions the amount of blood per person per practical session ranged from none, to one instance with a smear of blood. Based on tutor comments, no cows had to be withdrawn fr om th e post-intervention practical sessions. As with the pre-intervention results, each student needed to palpate at least four cows per class in order to reach the level of competence achieved, translating into approximately 20 instances of rectal palpation per stu- dent over the duration of the five practical classes. From these figures, it was calculated that for the five post-in- tervention palpation classes, a total of approximately 1.1 cows/student were required in order to achieve this level of competency. 3.3. Comments on the Computer Assisted Learning Material from Pre-Intervention Students Nine students from the initial year of the study who were Open Access OJVM  S. T. NORMAN, G. DALL’ALBA Open Access OJVM 325 Figure 3. The uptake of rectal palpation skills in the post-intervention cohort. A competency of 1 indicates the student is un- able to perform the task, 2 indicates the task was successfully completed for the first time, 3 indicates the task has been com- pleted on several occasions and that in the context of this study, the competency has been achieved. From left to right, the five columns for each procedure represent consecutive practical sessions (1 to 5). CL: Corpus Luteum; UA: Uterine Artery. shown the material in their subsequent (fifth) year of the veterinary science program unanimously and passion- ately agreed that had they been shown the material in their initial year of rectal palpation instruction, they would have more clearly understood the procedures they were supposed to be performing. They felt th ere was still substantial benefit in using the animations at their ad- vanced stage of the program as it refreshed their knowl- edge of the anatomy, reinforced the steps of the palpation technique and helped to prevent the development of bad habits as they could repeatedly refer back to the ideal technique. 4. Discussion This study investigated the effect of including a com- puter assisted learning tool in the Veterinary Reproduc- tion course in the Bachelor of Veterinary Science pro- gram. The learning tool was assessed by industry repre- sentatives who commended it as an accurate representa- tion of the palpation technique and current reproductive knowledge about the cow. In specifically addressing the first aim of the study, it was found that the CAL intervention enhanced students’ ability to visualise the anatomical relationships of the reproductive organs with other abdominal structures. Importantly, it seems likely that pre-intervention students did not recognise the difficulty of visualising this rela- tionship, nor its influence on their ability to competently complete the palpation task s. Prior to the rectal palpation practicals, these students had gained their anatomical understanding from practical classes that used abattoir specimens in static displays. Students in this pre-inter- vention cohort typically felt their understanding of the structures at the commencement of the palpation classes was adequate to complete the required palpation tasks in the live cow. However, when tutor comment was ana- lysed, it was evident that many of these students had a rudimentary visualisation and understanding of the struc- tures, particularly the position of the broad ligament (the membranous support structure) of the uterus. This may explain why many of the students couldn’t perform some of the higher level skills that require a detailed under- standing of the position of the broad ligament within the abdomen. Unfortunately, the structure and integrity of the broad ligament is lost when the reproductive tract of the cow is removed from the abdomen in the abattoir. The discrepancy between tutors’ and pre-intervention students’ skill assessment may be because tutors had difficulty interpreting exactly what students were feeling and doing while palp ating. However, considering that the tutors were experienced in their role, it seems more likely the students had difficulty comprehending some of the more challenging palpation procedures due to a lack of anatomical understanding. If anatomical relationships and procedures are not correctly understood, students may mistakenly believe they have completed a procedure,  S. T. NORMAN, G. DALL’ALBA 326 when they have only partially, or incorrectly, completed it. This was highlighted in the contrast between the stu- dent and tutor assessments in the pre-intervention group where 69% of students felt they had completed the uter- ine retraction procedure competently, compared to the tutor assessment of 25% of students. This example shows how a lack of understanding in one area may lead stu- dents to a false sense of competency in another. One year later, dramatically increased tutor assessment of levels of competency in the post-intervention cohort of students strongly supports the interpretation that pre-intervention students did not correctly visualise the abdominal struc- tures and procedures, and that the CAL intervention im- proved this visualisation. It was also apparent from the comparison of student and tutor assessments (80% and 81% respectively) that by the end of the practicals, post- intervention students accurately assessed whether they were successfully completing the uterine retraction pro- cedure. This could only occur if they were clear on what the procedure entailed. In addressing the second aim of the study, student sur- veys suggested cow rectal palpation skills were attained at approximately the same rate prior to and after the CAL intervention, although, as noted above, there were dis- crepancies between tutor and pre-intervention student assessments. Based on tutor survey, it is apparent that the skills were gained at an improved rate and to a higher level of competency by more students in the post-inter- vention group with the same number of practical classes, a larger number of students and the same number of cows. Therefore, it can be concluded that the CAL inter- vention can be used to enhance the skills, or parts of the skills, of rectal palpation in cattle. It also improved the efficiency of teaching cow rectal palpation with regard to live animal requirements. In cattle palpation practicals, it is important students do not feel at risk of injury so they can focus fully on completing their tasks. It is also essential that the welfare requirements of cattle used in teaching are continually assessed with a view to achieving the highest possible standard. With regard to the third aim of this study, re- sults indicate that in both pre and post-intervention prac- ticals, students felt at ease in the facilities they were us- ing. Both the student and tutor surveys indicated there was minimal discomfort to animals used in these practi- cal classes based on cow movement, vocalisation, or the presence of blood after palpation. There appeared to be a small improvement in individual cow welfare when the CAL tool was used. Importantly, when using the CAL tool, more students were taught more effectively from the same number of cows compared to when the in tervention was not used. This means less cows will be needed for a given competency outcome. The CAL tool could there- fore help to cater for increased numbers of students en- tering a veterinary degree program. The presentation of the CAL material on a web-based platform in this study had benefits and limitations. A major benefit was the ability to track how many times each student accessed the material. However, a limitation was that the file sizes for the animations were large enough to make viewing over telephone connections te- dious. Therefore, students could most readily access the material if they had personal high-speed internet access or while they were on campus. Thus, improvements could be made to ensure th e CAL tool is compatible with students’ available hardware and IT infrastructure. None- theless, an average of 20 access instances per student over the duration of the five classes suggests use of the resource was high. Provision of the material in CD-Rom format is a solution to the internet co nnection speed issue and would provide students with future learning and re- vision opportunities even after the formal course has been completed and access to animal tissue or live ani- mals is limited. Computer-based learning tools can engage students in learning, allow monitoring of usage and also provide opportunities to develop novel learning tools unavailable in traditional educational media. Consequently, one tool can stimulate a variety of senses in order to improve knowledge retention and skill development [1]. In addi- tion, the portability of digital media and the extensive access many students now have to computers is condu- cive to repetitive exposure to these tools. This is in con- trast to practical classes where live animals or biological specimens are required. The CAL tool used in this study sought to exploit these features of CAL in a way that was relevant to the Veterinary Reproduction course and sup- ported student learning in the course through authentic engagement. 5. Conclusion Some previous studies have shown that learning tech- nologies can support learners in achieving the necessary competence in preparation for the world of work beyond university studies [14]. If these technologies are to pro- mote relevant learning, it is essential that learners are engaged in meaningful, authentic activities. The study reported in this paper provides evidence that a technol- ogy-enriched environment can enhance this kind of learning when it is based on sound pedagogy. In tech- nology-enriched environments, sound pedagogy requires carefully designing the technology and embedding it within the task and course in a way that takes account of prior knowledge in promoting learning [3-5,15]. Demon- strating that learning has been improved through the use of these technologies can be a challenging task, as this study also highlights. These tools provide no guarantee of improved learning, but they have the potential to ex- Open Access OJVM  S. T. NORMAN, G. DALL’ALBA Open Access OJVM 327 tend and enhance our efforts towards promoting the learning of our students in ways that are relevant for the 21st century. 6. Acknowledgements We are grateful to John Bowden and Jenny Hyams for providing comments on an earlier version that enabled us to improve this article. REFERENCES [1] J. M. Naylor, “Learning in the Information Age: Elec- tronic Resources for Veterinarians,” Large Animal Vet- erinary Rounds, Vol. 5, No. 5, 2005, pp. 1-5. [2] M. Ryan, C. W. Mulholland and W. S. Gilmore, “Appli- cations of Computer-Aided Learning in Biomedical Sci- ences: Considerations in Design and Evaluation,” British Journal of Biomedical Science, Vol. 57, No. 1, 2000, pp. 28-34. [3] R. Ellaway , “Discipline-Based Designs for Learning: The Example of Professional and Vocational Education,” In: H. Beetham and R. Sharpe, Eds., Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing and Delivering E-Learning, Routledge, New York, 2007, pp. 153-165. [4] D. Laurillard, “Rethinking Teaching for the Knowledge Society,” Educause Review, Vol. 37, 2002, pp. 16-25. [5] R. Sharpe and M. Oliver, “Designing Courses for E- Learning,” In: H. Beetham and R. Sharpe, Eds., Rethink- ing Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing and Deliver- ing E-Learning, Routledge, New York, 2007, pp. 41-51. [6] S. Alexander and D. Boud, “Learners Still Learn From Experience When Online,” In: J. Stephenson, Ed., Teach- ing and Learning Online: Pedagogies for New Technolo- gies, Kogan Page, London, 2001, pp. 3-15. [7] G. Dall’Alba and R. Barnacle, “Embodied Knowing in Online Environments,” Educational Philosophy and The- ory, Vol. 37, No. 5, 2005, pp. 719-744. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2005.00153.x [8] M. C. Lynn and R. D. Twigg, “A New Approach to Clini- cal Remediation,” Journal of Nursing Education, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2011, pp. 172-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2005.00153.x [9] G. Conole, M. de Laat, T. Dillon and J. Darby, “‘Disrup- tive Technologies’, ‘Pedagogical Innovation’: What’s New Findings From an In-Depth Study of Students’ Use and Perception of Technology,” Computers & Education, Vol. 50, No. 2, 2008, pp. 511-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20101230-12 [10] S. B. Jephcott and S. T. Norman, “Pregnancy Diagnosis in Cattle,” Australian Cattle Veterinarians, Brisbane, 2004. [11] I. Treadwell, T. W. de Witt and S. Grobler, “The Impact of a New Educational Strategy on Acquiring Neonatology Skills,” Medical Education, Vol. 36, No. 5, 2002, pp. 441-448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01201.x [12] J. P. Finley, G. P. Sharratt, M. A. Na nton, R. P. Chen, D. L. Roy and G. Paterson, “Auscultation of the Heart: A Trial of Classroom Teaching Versus Computer-Based Independent Learning,” Medical Education, Vol. 32, No. 4, 1998, pp. 357-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00210.x [13] V. H. M. Dale, P. E. J. Johnstone and M. Sullivan, “Learning and Teaching Innovations in the Veterinary Undergraduate Curriculum at Glasgow,” Journal of Vet- erinary Medical Education, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2003, pp. 221-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/jvme.30.3.221 [14] C. Brown, J. Hedberg and B. Harper, “Metacognition as a Basis for Learning Support Software,” Performance Im- provement Quarterly, Vol. 79, No. 2, 1994, pp. 3-26. [15] A. Ravenscroft and J. Cook, “New Horizons in Learning Design,” In: H. Beetham and R. Sharpe, Eds., Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing and Delivering E-Learning, Routledge, New York, 2007, pp. 207-218.

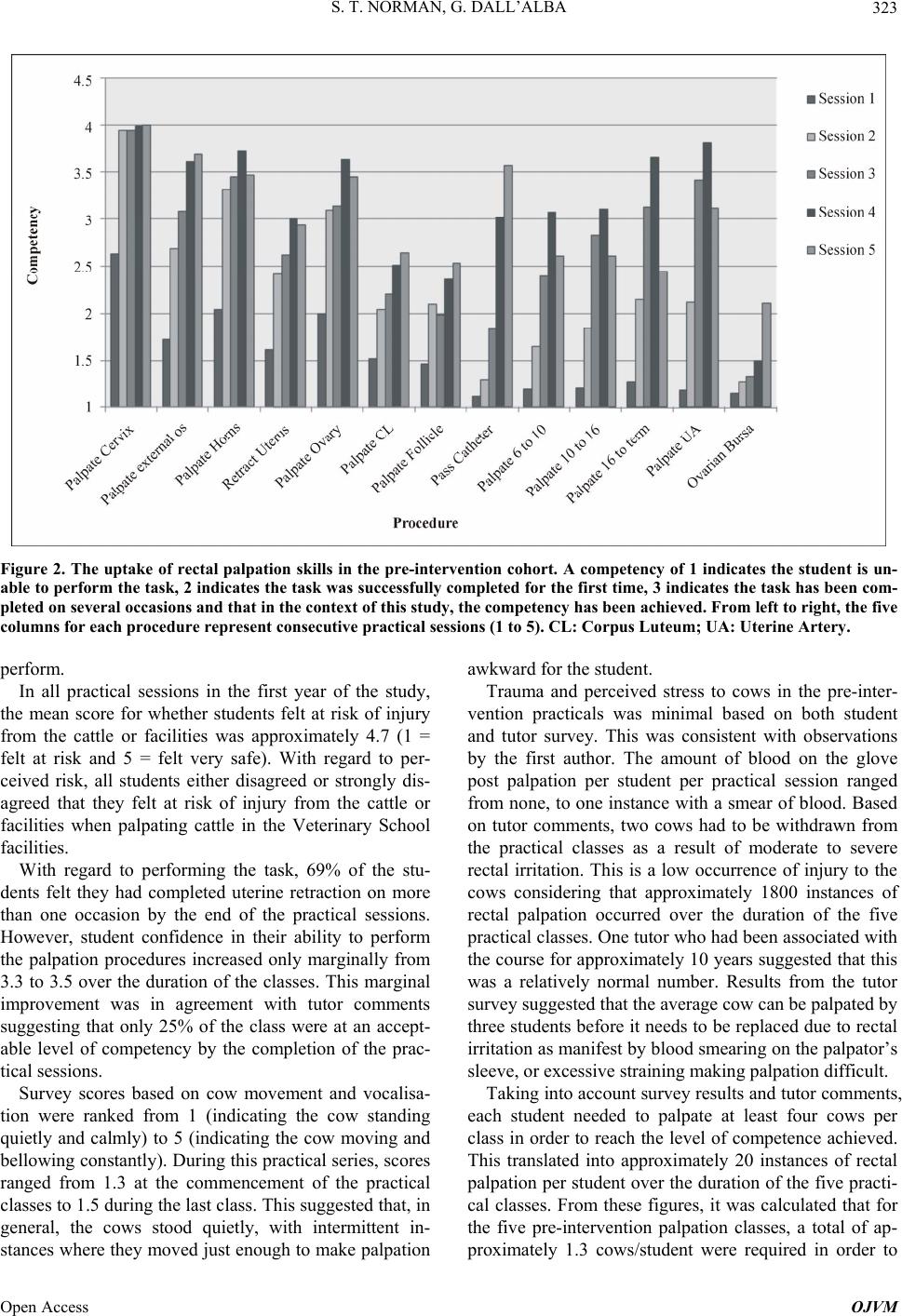

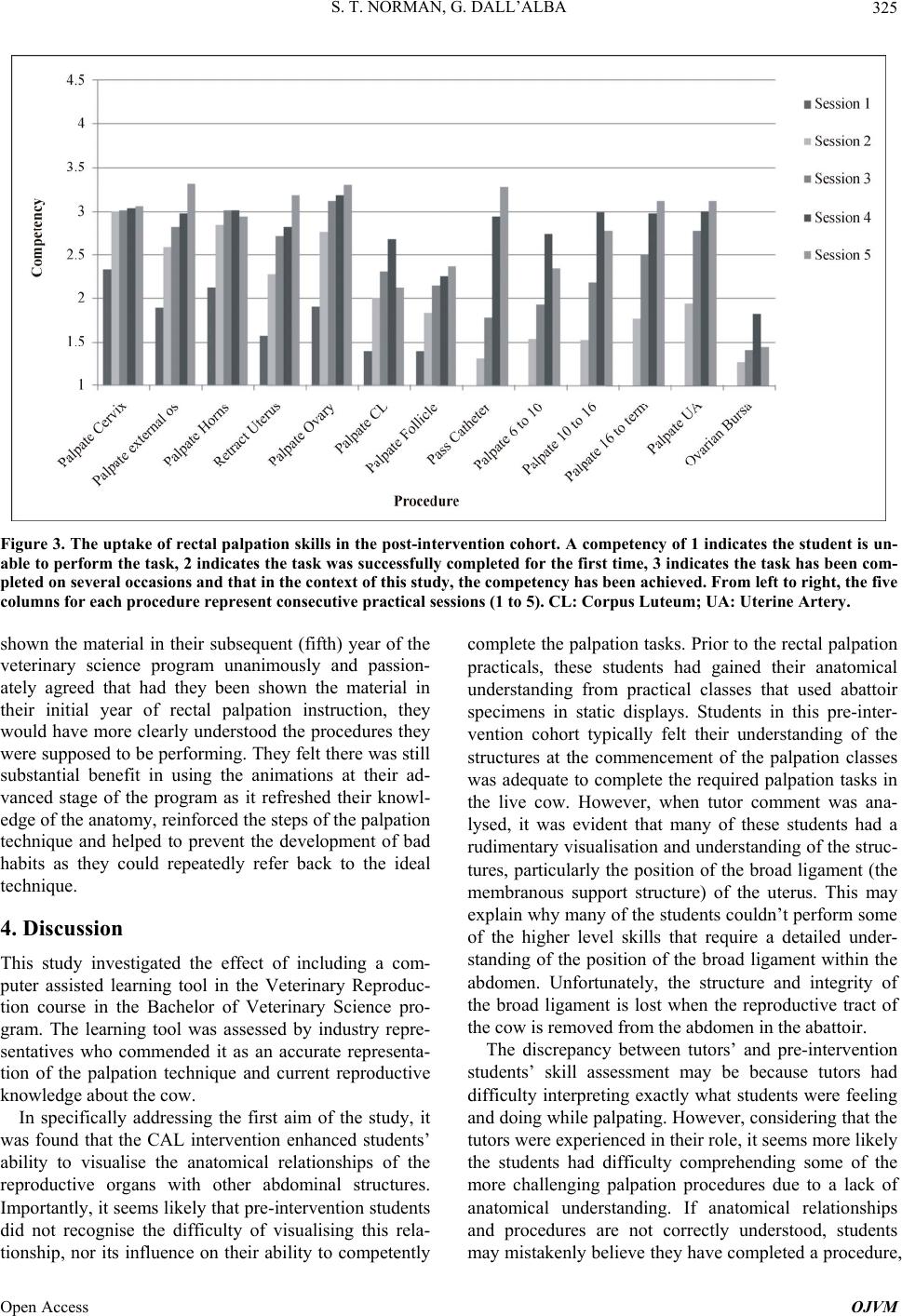

|