Open Journal of Social Sciences 2013. Vol.1, No.6, 32-39 Published Online November 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2013.16007 Open Access Personality and Heart Rate Variability: Exploring Pathways from Personality to Cardiac Coherence and Health Ada H. Zohar1, C. Robert Cloninger2, Rollin McCraty3 1Psychology, Ruppin Academic Center, Emek Hefer, Israel 2Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, USA 3Institute of Heartmath, Boulder Creek, USA Email: adaz@ruppin.ac.il, crcloninger@gmail.com, rollin@heartmath.org Received October 2013 Background: Personality and heart rate variability (HRV) are each strong predictors of well-being, par- ticularly cardiac health and longevity. The current project explores the correlates of personality traits on heart rate variability (HRV) to clarify how autonomic regulation may mediate the development and main- tenance of health and disease. Hypothesis: Personality traits will be significantly correlated with specific measures of HRV. In particular, the Character traits of Self-Directedness, Cooperativeness, and Self- transcendence are known to promote physical, mental, and social aspects of well-being, so they were ex- pected to be associated with indices of HRV indicating autonomic balance. Methods: Participants were 271 volunteers from the community, adult men and women. They received an extensive self-report ques- tionnaire, allowing for a comprehensive personality evaluation. Of these participants, 118 underwent am- bulatory—24 hours recording of HRV. The HRV recordings were sent to the Institute of HeartMath for interpretation. Data Analysis: Data for personality was retrieved from the Qualtrics site after online ad- ministration, into which the HRV data were entered. Analyses were conducted in SPSS 20. Results: Sys- tematic and significant associations between personality traits were found. In particular, the Temperament and Character Inventory’s character traits were related to autonomic balance as measured by the ratio of low frequency (sympathetic) to high frequency (parasympathetic) activity. Openness, aggression, avoid- ant attachment, and forgiveness were found to relate to several HRV variables. Conclusion: The relations among personality and HRV support the validity of the measures in ways that clarify the strong relations among personality, HRV, and health. Further work to replicate and extend these preliminary findings in a larger sample is underway. Keywords: TCI; HRV; Openness; Forgiveness; Personality; Health Introduction Personality Measures and H e alth There is a strong link between personality and health—phys- ical health in general and cardiac health in particular. Personal- ity influences health via several active pathways. There is a relationship between personality and adopting a healthy life- style (HLS). For example, personality influences the proba- bility of smoking (Zohar & Cloninger, 2011), of eating a healthy diet (van de Bree, Przybeck, & Cloninger, 2006), of exercising (Raynor & Levine, 2009), and of seeking appropri- ate and timely medical attention. Personality has considerable influence on adopting an HLS, and HLS is an obvious pathway to health. However, HLS does not fully explain the covariance of personality and health, demonstrating that there are addition- al pathways (Edmonds, 2011). Personality influences the perception of stress by an individ- ual both in everyday social interactions (Uliaszek et al., 2012) and when faced with major life challenges (van Zuidena et al., 2011). In particular childhood adversity seems to exercise an enduring effect on health and vitality that affects individuals even into old age (Surtees et al., 2011). Stress, and especially emotional stress, has been shown to pave multiple routes to ill-health: by affecting the immune system, the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, chronically increased levels of serum cortisol, and by way of chronic hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011). Childhood adversity, such as neglect or abuse, is also associated with impaired character development (Josefsson et al., 2013b), insecure attachment (Kwako et al. 2013), and ag- gression (Hiramura et al., 2011) as well as epigenetically alter- ing the function of the immune system (Cole et al., 2010). The manner in which personality is defined and measured affects the research results on links between personality and health. The empirically derived big five factor (BF) personality traits of low Neuroticism and high Conscientiousness have been linked to adaptive health behavior (Lodi-Smith et al., 2011), cardiac health (Chapman & Goldberg, 2011), and lon- gevity (Chapman, Fiscella, Kawachi, & Duberstein, 2010). The theoretically derived temperament and character bio-psycho- social model of personality, measured by the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) has been associated with increased risk for psychiatric disorders (Cloninger, Zohar, Hirschmann, & Dahan, 2012), response to a wide range of psychiatric and other medical interventions, and cardiac risk factors (Hintsanen et al., 2009) (Rosenstrom et al., 2012). The B F and TCI traits can also be dichotomized to above and below the median, and combined to form multidimensional personality profiles associated with health and well-being (Cloninger & Zohar, 2011; Rosenstrom et al., 2012).  A. H. ZOHAR ET AL. Open Access Personality can affect autonomic function and dynamics. In- creased neuroticism is linked to increased SNS activation, as measured by increased electro-dermal response, as well as in- creased anticipatory anxiety (Drabant et al., 2011). Individual differences in the BF personality traits are linked to individual differences in electrocardiogram (ECG) amplitude patterns, in particular high Neuroticism and low positive emotion (Koelsch, Enge, & Jentschke, 2012). Heart Rate Variability Heart rate variability (HRV) is measured by the variability of beat-to-beat intervals, and is an indicator of health and well- being in the general population (Antelmi et al., 2004). High HRV is associated with reduced medical morbidity and in- creased longevity (Matsuoka et al., 2005), and higher cognitive functioning. Low HRV is a predictor of risk for myocardial infarct (MI), and sudden cardiac death, and all-cause mortality while high HRV is a predictor of recovery from MI (Carney et al., 2001; Ablonskytė-Dūdonienė et al., 2012). Consequently differences between people in HRV strongly predict their rates of morbidity and mortality, including both physical and psy- chological aspects of health (Araujo et al., 2006). Variation in HR results mainly from physica l exertion (Grant, Vilijoen, van Rensburg, & Wood, 2012) but also from res- ponses to internal and external stimuli, especially novel stimuli that may be interpreted as threatening (Thayer, Ahs, Fredriksen, Sollers III, & Wager, 2012). While the heart provides a rela- tively steady underlying rhythm, this rhythm is affected by the slowing (inhibitory) influence of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) and the accelerating (excitatory) effect of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The average heart rate of 70 - 80 reflects a relative balance between the action of the two components of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), the PNS and the SNS. In ambulatory recordings the ratio of low to high frequency (LF/HF ratio) is a useful indicator of the relative balance between the activity in the sympathetic and parasym- pathetic systems. Several measures of different components of heart rate variability can be reliably measured to assess the characteristics and changes of an individuals, autonomic func- tioning over time (Voss, 2007). For example, HRV is greater in the young, and in the physically fit, and decreases with age (Task Force of European Society of Cardiology et al., 1996; Antelmi et al., 2004). HRV is also a finely tuned measure of heart-brain communi- cation, as well as a strong predictor of morbidity and death. We expect that a better understanding of HRV in relation to indi- vidual differences in personality and life-style choices will contribute to improved medical diagnosis and treatment. While the average heart rate (HR) is relatively easy to measure over a short time period, its variability can be more challenging to measure reliably (Jarrin et al., 2012). In order to insure high reliability of HRV measurement, 24 hour ambulatory record- ings can be made, as was done in the current study, so that the HRV variables are calculated over a long sampling window across the full range of a person’s daily activi ties. The 24-hour ambulatory recording increases the ecological validity of the HRV measurement, and hence its relevance to self-regulatory mechanisms by which personality may mediate and modulate the relationship between HRV and health. Personality is a way of describing the way a person has learned to adapt to their life circumstances. Temperament traits are moderately stable throughout the life span on average, but character traits continue to develop in response to the demands of life roles and social norms throughout the lifespan (Clonin- ger, 2003; Josefsson et al., 2013a). Specifically, Self-directed- ness and Cooperativeness increase as needed to facilitate a person’s responsibility for work and social relatedness to about age 45 years. Self-transcendence decreases through age 45 and then later increases again in response to the challenges of ulti- mate situations like suffering and imminent mortality (Clo- ninger, 2003; Josefsson et al., 2013a). The maturation of cha- racter traits appears to be a way to promote and maintain health by facilitating healthy self-regulation of emotional reactions and lifestyle choices (Cloninger et al., 2010; Cloninger et al., 2012). In particular, higher levels of the character traits of Self- directedness, Cooperativeness, and Self-transcendence are all associated with positive emotions, satisfying social relations, and perceived physical health (Cloninger & Zohar, 2011). Out - looks on life characterized by positive emotions and a sense of connectedness have been shown to promote psychosocial func- tioning and psychophysiological coherence including increased HRV and improved synchronization in ANS dynamics (Bradley et al., 2010; McCraty et al., 1999). In prior work we have shown that individual differences in personality influence the physical, mental, and social aspects of health and well-being (Cloninger et al., 2010; Cloninger & Zohar, 2011). Personality affects the individual’s emotional state, autonomic stability, immune response, capacity to self- regulate stress, as well as health behavior and response to med- ical treatments. The current study undertakes an integrative and comprehensive measurement of personality in order to look for pathways from personality to HRV. Because of its exploratory nature, the study was designed to measure many different per- sonality traits that might contribute to increased HRV and resi- lience. Methods Personality Measures The Temperament and Character Inventory in Hebrew (TCI), is based on a neuropsychological and genetic understanding of brain structure and activity. It measures four temperament scales and three character traits. The Hebrew version has ex- cellent psychometric properties and predictive validity for sub- jective and objective health (Zohar & Cloninger, 2011). DS14 in Hebrew (Zohar, Denollet, Lev-Ari, & Cloninger, 2011) has 14-items and is made up of two subscales, negative affect (NA) and social inhibition (SI). Posited by Denollet (Denollet, 2005) in the context of cardiac health, it awards a score of Type D to individuals who score 10 and above on both dimensions, and Non D to those who do not. The Big Five Factor Brief Inventory in Hebrew (BFI44; Et- zion & Lasker, 1998), measures the big five factors of perso- nality: Openness, Agreeableness, Extroversion, as well as Con- scientiousness and Neuroticism. The latter two have been found to be highly predictive of HLS, health and longevity. The BFI44 in Hebrew has excellent psychometric properties and has been widely used in research. Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS20, Bagby, Parker, & Tay- lor, 1994) measures difficulty in identifying, describing and relating to one’s own feelings. This 20-item scale has excellent psychometric properties in the original English, was translated with permission into Hebrew, and found to have excellent  A. H. ZOHAR ET AL. Open Access structural and predictive validity as well as high scale reliability (Zohar & Cloninger 2011). Trait Forgivenes s Scale (TFS; Berry, Worthington , O’Connor, Parrott III L., & Wade, 2005) is a 10-item scale asking about the degree to which individuals are able to forgive and forget rather than carry a grudge. The original scale has excellent psy- chometric properties; it was translated for the proposed study by a process of translation, independent back-translation, and revision. Aggression Questionnaire—is a 29-item inve ntory with ex- cellent psychometric properties in the original English (Buss & Perry, 1992) as well as in the Hebrew translation (Al-Krenawi, Graham, & Kanat-Maymon, 2009). It has four subscales: hos- tility, anger, physical aggression, and verbal aggression. Meaning in Life Questionnaire (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006) includes 10 items about interest in finding mean- ing and attainment of a sense meaning. It has good psychome- tric qualities in the original, and has been translated and used in research in Hebrew with good results. Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES- D; Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item depression symptom scale, as- sessing a one-week time frame, designed as a general-popu- lation-screener, with an excellent translation into Hebrew. Authentic Happiness Scale (AHI; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). The AHI is designed to measure changes in happiness over time. It has 24 multiple choice questions that encompass four areas of potential happiness: pleasure, engage- ment, achievement, and meaning. The original scale has excel- lent psychometric properties; it was translated for the proposed study by a process of translation, independent back-translation, and revision. The AHI was designed to be sensitive to changes in happiness over time. The CES-D and the AHI scores should be negativel y correlated . Positivity scale (Caprara et al., 2012) is an 8-item inventory of positive evaluations of the self, answered on a 5-category Likert-like response scale that adds explained variance to the BFI model and is independent of the five factors. It was trans- lated (with permission) for the proposed study by a process of translation, independent back-translation, and revision. The Experiences in Close Relationships Short Scale (ECR; Wei, Russell, Malinckrodt, & Vogel, 2007), is a 12-item ques- tionnaire designed to assess attachment style in adults. It has anxiety and avoidance subscales, yielding two continuous scores, as well as dividing individuals into 4 types, acc or ding to their score vs the median on the two scales. It has been found to be reliable and valid, and highly predictive of emotion and emotion regulation. HRV Measurement HRV was recorded using a First beat Body Guard recorder, a lightweight accurate recorder of HRV with a sample rate of 1000 Hz, which is attached with two snap-on electrodes to the chest, for 24 hours. Originally designed for use during athletic training, it weighs only 24 grams and is small in size, so partic- ipants reported that they were able to forget about it and to go about their daily activities as usual. The monitors were con- nected when the batteries were fully charged, allowing for a margin of time to disconnect and download the recordings. The recording was then uploaded for analysis to the Institute of HeartMath (IHM) in CA. The Autonomic Assessment Report (AAR) issued by IHM after expert manual inspection for ire- gularities included time domain and frequency domain (i.e., power spectral density) variables. Both the time domain and the frequency domain analyses have advantages and disadvantages. The time domain measures are the simplest to calculate but do not provide as good of a means to quantify the various underlying rhythms in the HRV or autonomic balance. The heart rate (HR) generated by the sinoatrial node in the absence of any neural or hormonal influ- ence is about 100 to 120 beats per minute (Hainsworth, 1995). The HR of a healthy person reflects the net balance between the activity of the parasympathetic (vagal) nerves, which slow it and the sympathetic nerves, which accelerate it. Both the sym- pathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nerv- ous system are tonically active in healthy people, but the para- sympathetic branch dominates during rest and digestion whe- reas the sympathetic branch dominates during aggressive or avoidant (“fight or flight”) responses to stress or challenge and during physical exercise. The heart responds to parasympathetic stimulation of the sinus node much more quickly than it does to sympathetic stimulation. Thus in the absence of arrhythmias, high frequency (fast) responses indicate parasympathetic acti- vation whereas lower frequency (slow) responses indicate sympat hetic activity. In the time domain the most important measures are heart rate, SDNN, the SDNN Index, and RMS-SD. SDNN is the standard deviation of the time interval between successive normal heart beats (i.e., the RR intervals) in the 24-hour re- cording, and reflects all influences on HRV including slow influences across the day, circadian variations, the effect of hormonal influences such as cortisol and epinephrine. The SDNN Index is the mean of the standard deviation of all the normal RR intervals for each 5-minute segment of the 24-hour recording, and reflects rhythms operating within a 5-minute segment only. The RMS-SD is the root mean square of the RR intervals (i.e., square root of the mean of the squared differenc- es in time between successive normal heart beats), so it reflects high frequency (fast or parasympathetic) influences on HRV (i.e., those influencing larger changes from one beat to the next). In the frequency domain analysis, measures of different fre- quencies of HRV are extracted by Fast Fourier Transforms of the 5-minute segments, thereby excluding the ultra-low fre- quency (ULF) influences on heart rate related to circadian in- fluences, such as hormonal release, that are measured in analy- sis of the 24-hour data. The variance (i.e., power) in HRV is measured in three bands of the frequency distribution of the Fourier transforms of the 5-minute segments: Very Low Fre- quency (VLF, .003 to .04 Hz), Low Frequency (LF, .04 to .15 Hz), and High Frequency (HF, .15 to .40 Hz). The power in HF bands reflects fast changes in beat-to-beat variability due to parasympathetic (vagal) activity, whereas that in the VLF band is thought to reflect an intrinsic rhythm produced by the heart which is modulated by primarily by sympathetic activity. The HF band is sometimes called the respiratory band because it corresponds to HRV changes related to the respiratory cycle and can be increased by slow, deep breathing (about 6 or 7 breaths per minute) (Kawachi et al., 1995) and decreased by anticholinergic drugs or vagal blockade (Hainsworth, 1995). The LF band reflects a mixture of sympathetic and parasympa- thetic activity, but in long-term recordings like ours, it reflects sympathetic activity and can be reduced by the beta-adrenergic antagonist propanolol (McCraty & Atkinson, 1996). In addi-  A. H. ZOHAR ET AL. Open Access tion to analyzing the 5-minute segments, a spectral analysis is carried out with the entire 24-hour period as one record to ex- tract the ULF (below .003) variability due to circadian influ- ences. The natural logarithm of the ratio of LF to HF power (Ln LF/HF) is the main indicator of autonomic balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. When a person is in a state of psychophysiological coherence characterized by a sine wave pattern in the HRV at a frequency of 0.1 Hertz, the LF/HF falls greatly because of increased parasympathetic activ- ity and/or decreased sympathetic activity. Psychophysiological coherence is a state of calm alertness that occurs naturally with sustained positive emotions and can be induced by slow, deep breathing. More subtle reductions in this ratio occur with activ- ities that increase efferent parasympathetic activity such as when relaxing, sleeping, or with positive moods states. On the other hand, when a person is stressed, aggressive, or defensive, the LF/HF rises due to increased sympathetic activity and/or decreased par asympathetic activity. Parti cipant s 271 adult community volunteers, men and women, who had participated in a previous study of personality and health which took place between 2006 and 2010 (Zohar & Cloninger, 2011) completed the online personality self-report. Of these, 118 in- dividuals were also measured for 24-hour HRV. Inclusion cri- teria were level of Hebrew good enough to self-report on a questionnaire, and mobility (coming to the laboratory for the study). Exclusion criterion was a known heart rate disorder. On analysis, 14 of the participants (11 of them men) turned out to have an unusable recording, mostly due to a (unreported) heart rhythm disorder. Therefore, 104 participants’ data were in- cluded in the analyses. These participants were 46 to 79 years old (mean 61.4, SD 8.7) of whom 37.5% were men. Ethical Review The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the In- stitutional Review Board. Participant’s privacy was protected and data safety ensured. No pressure to participate or to con- tinue participation was brought to bear. Participants signed an informed consent form after a discussion of the study with the experimenter, and the experimenter co-signed the form in the participant’s presence. Results No significant differences in any personality variables meas- ured at outset (2006-7) (N = 1102) and the current assessment (N = 104) were found. Thus there was no self-selection for participation in the current study based on personality variables that might bias the results. Our main index of autonomic balance was Ln (LF/HF). We also examined the correlations between all primary HRV va- riables and a wide range of personality variables. We expected that consideration of several of the HRV variables and perso- nality variables would help to clarify the interpretation of the complex non-linear relationships between personality and au- tonomic regulation. We found that HRV was related to perso- nality in very specific ways, indicating substantial construct and discriminant validity of both the HRV and the personality va- riables. We report only on personality variables which had sig- nificant correlations with at least one HRV variable. Of the TCI traits, all three character traits correlated nega- tively with Ln (LF/HF), indicating that a more mature character development was associated with greater parasympathetic ac- tivity (vagal tone) and lower overall sympathetic activity. As the TCI theory predicts that better emotional regulation (and higher HRV) will be related to an overall rise in all three cha- racter traits, we also examined Creativity, the product of all three character traits. Creativity is defined here as the synergis- tic quality arising from the combination of high Self-directed- ness (i.e., resourceful, realistic), high Cooperativeness (i.e., reasonable, helpful), and high Self-transcendence (i.e., imagin- ative, intuitive) (Cloninger 2004). Although using the product also increases measurement error multiplicatively, the correla- tion between Creativity and Ln (LF/HF) is higher than the cor- relation of each character trait separately, supporting a non- linear association of character with HRV. In contrast, being organized (high Self-directedness and Cooperativeness but low Self-transcendence) or being fanatical (high Self-directedness and Self-transcendence but low Cooperativeness) were not significantly associated with LF/HF. These results are presented in Table 1. Table 2 presents relationships of other personality traits with the HRV variables included in the study. Openness is negatively correlated with many of the HRV variables, including those indicative of lower sympathetic activity (negative correlations with SDNN Index and ULF power) and those indicative of low parasympathetic activity (negative correlations with RMS-SD and Ln LF/HF). Low activity for both branches of the auto- nomic nervous system suggests that heart rate variability is only weakly regulated in people high in Openness, but parasympa- thetic regulation is relatively greater than sympathetic influ- ences (i.e., correlation with Ln LF/HF is negative). In contrast, Physical Aggression was associated with high sympathetic activity (indicated by positive correlation with SDNN, SDNN Index, LF, and VLF power, and no significant correlation with RMS-SD) whereas Avoidant Attachment was associated with lower parasympathetic activity (indicated by negative correla- tions with RMS-SD and Ln LF/HF). Circadian regulation of HRV is also weak in people high in Openness (indicated by no significant correlation with ULF in 24 hour analysis), so the HRV observed in relation to Openness is really unregulated reactivity to transient stimuli combined with ease of relaxation when unchallenged. Not shown in Table 2, Agreeableness was correlated r = .199* (p < .05) Ln (HF5), an indicator of high parasympathetic activity and Forgiveness was correlated with SDANN, an indicator of low sympathetic activity, r = −.224 (r Table 1. Correlations between TCI traits and HRV measures. TCI Traits Ln (LF/HF) Self -Directedness −.199* Cooperativeness −.199* Self-Transcendence −.197* Creative −.277** Organized Ns Fanatical Ns Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; Creative = SD X CO X ST; Organized = SD X CO X (STmax-STscore); Fanatical = SD X (COmax-COscore) X ST.  A. H. ZOHAR ET AL. Open Access Table 2. Correlations between openness, physical aggression, avoidant attach- ment and HRV measures. Openness Physical aggression Avoidance SDNNI −.222* .244* ns SDNN −.216* .216* ns SDANN −.233* ns ns RMS-SD −.209* ns −.234* Ln TP5 −.202* .277** ns Ln ULF24 −.247* ns ns Ln VLF5 −.217* .254** ns Ln LF5 ns .322** ns Ln HF5 ns ns −.328** Ln LF/HF −.217* .229* .318** Note: *p < .05; *p < .01. < .05). Choosing just two of the HRV variables for further scrutiny, we conducted hierarchical linear regression with one dependent variable from the power spectrum analysis, specifically the natural log of the ratio of low frequency (sympathetic) compo- nent to the high frequency (parasympathetic) component (Ln (LF/HF)), and also one dependent variable from the time do- main analysis, specifically the SDNN Index, which is the mean of standard deviation of the RR intervals for all the 5 minute intervals of the 24-hour recording. We considered age as first block predictor and personality traits as second block predictors. The results are presented in Tables 3 and 4. In the Power Spec- trum analysis, personality traits explained 23.1% of the va- riance in Ln (LF/HF), being creative decreased the ratio whe- reas being forgiving, physically aggressive and being avoi- dantly attached increased the ratio, so that creativity was asso- ciated with greater vagal (parasympathetic) activity whereas the other variables had greater sympathetic activity and/or lower parasympathetic activity. In the Time domain analysis, perso- nality traits explained 10.6% of the variance in the SDNN In- dex: being creative and being physically aggressive had greater HRV whereas being open had lower HRV on this indicator of sympat hetic ac tivity. I ncluded in Tables 3 and 4 are the second models, those with personality traits entered after the first pre- dictor age at time of measurement. Discussion The ratio Ln (LF/HF) is of considerable psychological and physiological interest. It is considered a measure of balance between the excitatory action of the SNS and the inhibitory action of the PNS over the 24-hours. However, the interpreta- tion of the associations found between personality traits and the ratio requires consideration of concomitant relations with indi- cators that can dissociate sympathetic and parasympathetic inputs. For example, high levels of sympathetic activity are indicated by high values for the time-domain variables of SDNN and SDNN Index and by the frequency domain va- riables of LF, VLF, which we observed to be positively corre- lated with self-reported Physical Aggression. On the other hand, high levels of parasympathetic activity are indicated by high values on the time-domain variable of RMS-SD (which was Table 3. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for personality variables predicting the frequency domain variable Ln (LF/HF). Model 2 Variable B SE B β Age −.007 .004 −.161 Creativity .001 .001 −.208* Forgiveness .123 .055 .219* Physical aggression .224 .094 .222* Avoidance .115 .040 .281** R2 .234 F for change in R2 6.34 Note: *p < .05; **p < .005. Table 4. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for predicting the time domain indicator of sympathetic influences on HRV, SDNNI total. Model 2 Variable B SE B β Age −.127 .174 −.072 Creativity .001 .001 .298** Openness −6.801 2.357 −.326** Physical aggression 7.556 3.294 .230** R2 .108 F for change i n R2 3.78** Note: *p < .05; **p < .005. correlated negatively with Openness and with Avoidant At- tachment) and the frequency-domain variable of HF (which was correlated positively with Agreeability and negatively with Avoidant attachment). The present study found that being creative (the product of the three TCI character traits) was negatively associated with the LF/HF ratio. A reasonable interpretation would be that more mature and developed character (Cl oninger, Svrakic, & Svrakic, 1997) is associated with more PNS inhibitory activity, as a form of mature emotional regulation that arises from an outlook of unity and connectedness with other people and one’s sur- roundings (Cloninger, 2004; Cloninger et al., 2010; Cloninger, 2013). This finding of the relationship between creativity and high vagal tone indicates that an outlook of unity allows a per- son for function efficiently in a state of calm awareness without unhealthy psyc hophysiological ar ousal or de fensiveness (B radley et al., 2010; McCraty et al., 2009). In other words, people with a creative character configuration who are highly self-directed, cooperative, and self-transcendent can function well while re- maining calm and happy in the face of the challenges of daily life (Cloninger, 2013). They are healthy beca use of their a bility to let go rather than to defend themselves with aggression or avoidance (“fight or flight”). They are able to remain alert and think clearly by being calm and happy (Fredrickson and Losada 2005). Their physiological coherence promotes resilience and maintains health (Bradley et al., 2010; Cloninger et al., 2012; Cohn et al., 2009). Measures of HRV provide an objective set of indicators of this creative and coherent way of adapting to  A. H. ZOHAR ET AL. Open Access life challenges. The finding that Creativity was characterized by a lower Ln (LF/HF) is noteworthy because other character profiles that include high Self-directedness were not associated with such autonomic activity. Creativity was measured as the synergistic strength that emerges from the combination of being Self-di- rected (i.e., resourceful and realistic), Cooperative (i.e., rea- sonable and helpful), and Self-transcendent (i.e., imaginative and intuitive). The other healthy character profile is being or- ganized, that is, highly self-directed and cooperative, but not self-transcendent. Being organized was not significantly asso- ciated with autonomic balance, suggesting that self-transcen- dence is crucial for autonomic balance at least under the chal- lenging conditions of rapid change we face in the world today (Cloninger, 2013). However, people who are high in Self-di- rectedness and Self-transcendence but not Cooper ativeness (i.e., hostile fanatics) are also not functioning in a state of cardiac coherence according to our observations. Therefore, it is the synergy between all three components of character measured by the TCI that is crucial for functioning with an outlook of unity and connectedness that includes respect for one’s self, other people, and the world as a whole. In contrast, Openness is negatively correlated with many of the HRV variables, including those indicative of lower sympa- thetic activity (negative correlations with SDNN Index and ULF) and those indicative of low parasympathetic activity (negative correlations with RMS-SD and Ln LF/HF). Low ac- tivity for both branches of the autonomic nervous system sug- gests that heart rate variability is only weakly regulated in people high in Openness, even though parasympathetic regula- tion is relatively greater than sympathetic influences (i.e., the correlation with Ln (LF/HF) is negative). Circadian regulation of HRV is also weak in people high in Openness (indicated by no significant correlation with ULF in 24 hour analysis), so the HRV observed in relation to Openness is really unregulated reactivity to transient stimuli combined with ease of relaxation when unchallenged. Physical Aggression was associated with high sympathetic activity (indicated by positive correlation with SDNN, SDNN Index, LF, VLF), but was not related to any differences in pa- rasympathetic activity (indicated by no significant correlation with RMS-SD). In contrast, Avoidant Attachment was asso- ciated with low parasympathetic activity (indicated by negative correlations with RMS-SD and Ln (LF/HF)). On the other hand, Agreeableness was correlated with an indicator of high para- sympathetic activity (positive correlation with HF) whereas Forgiveness was correlated with an indicator of lower sympa- thetic activity (neg ative correlation with SDANN). Consequently, in the multiple regression analysis of auto- nomic balance measured by Ln (LF/HF), being creative de- creased the ratio whereas being physically aggressive, avoidant, and/or simply forgiving increased the ratio. In other words, creative functioning, such as non-violent assertiveness, is cha- racterized by greater vagal (parasympathetic) regulation to maintain autonomic balance whereas other personality variables depend on either greater sympathetic activity and/or lower pa- rasympathetic activity. Creative problem-solving with a calm, happy outlook of unity is more integrative and adaptive than defensive responding (i.e., aggression or avoidance) or submis- sive responding (i.e., agreement or forgiveness). In the multiple regression analysis of the SDNN Index, which is the mean of the standard deviation of the time interval between successive normal heart beats (i.e., the RR intervals) throughout the day, being creative or being physically aggres- sive contributed to greater HRV. In contrast, once creativity and physical aggression were taken into account, being open resulted in lower HRV, even though the SDNN Index is consi- dered to indicate mostly sympathetic activity. This finding fits with the interpretation that openness is associated with weak regulation of cardiorespiratory reactivity: once the strong active influences of creative or aggressive responses are taken into consideration, openness is not associated with increased HRV. The results presented here should be considered in the light of the study limitations. Self-report questionnaires are highly reliable but imperfect measures of personality. All personality measures have measurement error due to a variety of known causes as well as random effects (Schmidt & Hunter, 1996). Because this is an exploratory study we used a wide range of personality instruments, and many of them did not associate systematically with HRV variables. The personality variables we reported on were those that had at least one two-tailed sig- nificant correlation at p ≤ .05 with at least one of the HRV va- riables included in the analyses. Casting a wide net as we did, all results should be viewed as hypothesis-generating, rather than as conclusive. In addition, the measurement of HRV is restricted in the study to 104 complete records. The measurement of HRV is highly reliable and ecologically valid because it is conducted over 24 hours and the analyses of the data were conducted by expert technicians and physiological psychologists. The inter- pretation of our results should be viewed with these reserva- tions in mind. The results of this study require replication. However, they sketch intriguing pathways through personality traits, emotional response, CNS action, and heart activity. The regulation of cardiorespiratory functioning through the autonomic nervous system may be an important way by which personality jointly influences the physical, mental, and social aspects of health and well-being. REFERENCES Ablonskytė-Dūdonienė, R., Bakšytė, G., Ceponienė, I., Kriščiukaitis, A., Drėgūnas, K., & Ereminienė, E. (2012). Impedance cardiography and HRV for long-term cardiovascular outcome prediction after MI. Medicina, 48, 350-358. Al-Krenawi, A., Graha m, J. R., & Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2009). Analysis of trauma exposure, symptomatology and functioning in Jewish Is- raeli and Palestinian adolescents. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195, 427-432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.050393 Antelmi, I., de Paula, R. S., Shinzato, A. R., Peres, C. A., Mansur, A. J., & Grupi, C. J. (2004). Influence of age, gender, body mass index, and functional capacity on heart rate variability in a cohort of sub- jects without heart disease. American Journal of Cardioliogy, 93, 381-385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.09.065 Araújo, F., Antelmi, I., Pereira, A. C., Latorre, M. R., Grupi, C. J., Krieger, J. E., & Mansur, A. J. (200 6), Lower heart rate variability is associated with higher serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein con- centration in healthy individuals aged 46 years or more. Internsl Journal of Cardiology, 107, 333-337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.03.044 Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., & Taylor, G. J. (1994). The 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale-I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic R esearch, 38, 23-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1 Berry, J. W., Worthington, E. L., O’Connor, L. E., Parrott III, L., & Wade, N. G. (2005). Forgivingness, vengeful rumination, and affec-  A. H. ZOHAR ET AL. Open Access tive traits. Journal of Personality, 73, 183-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00308.x Bradley, R. T., McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tomasino, D., Daugherty, A., & Arguelles, L. (2010). Emotion, self-regulation, psychophysio- logical coherence, and test anx iety: Results from an experiment using lectrophysiological measures. Applied sychophysiological Biofeed- back, 35, 261-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10484-010-9134-x Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452-459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452 Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., Eisenberg, N., Kupfer, A., Steca, P., Caprara, M. G., Yamaguchi, S., Fukuzawa, A., & Abela, J. (2012). The positivity scale. Psychological Assessment, 24, 701-712. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0026681 Carney, R. M., Blumenthal, J. A., Stein, P. K., Watkins, L., Catellier, D., Berkman, L. F., Czajkowski, S. M., O’Connor, C., Stone, P. H., & Freedland, K. E. (2001). Depression, heart rate variability, and acute myocardial infarction, Circulation, 104, 2024-2028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/hc4201.097834 Chapman, B. P., & Goldberg, J. R. (2011). Replicability and 40-year predictive power of childhood ARC types. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 593-606. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024289 Chapma n, B. P., Fiscella, K., Kawachi, I., & Duberstein, P. R. (2010). Personality, socioeconomic status, and all-cause mortality in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171, 83-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp323 Cloninger, C. R. (2003). Completing the psychobiological architecture of human personality development: Temperament, character, and coherence. In U. M. Staudinger, & U. E. R. Lindenberger (Eds.), Understanding human development: Dialogues with lifespan psy- chology (pp. 159-182). London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0357-6_8 Cloninger, C. R. (2004). Feeling good: The science of well-being (p. 374). New York: Oxford University Press. Cloninger, C. R. (2013). What makes people healthy, happy, and ful- filled in the face of current world challenges? Mens Sana Mono- graphs, 11, 16-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.109288 Cloninger, C. R., & Zohar, A. H. (2011). Personality and the p erception of health and happiness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 128, 24-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.012 Cloning er, C . R., Sallou m, I. M., & Mezzi ch, J. E. (201 2). The dynamic origins of positive health and wellbeing. International Journal of Person-Centered Medicine, 2, 1-9. Cloninger, C. R., Svrakic, N. M., & Svrakic, D. M. (1997). Role of personality self-organization in development of mental order and disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 881-906. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S095457949700148X Cloning er, C. R., Zohar, A. H ., & Cloning er, K. M. (2010). Promotion of well-being in person-centered mental health care. Focus, 8, 165- 179. Cloninger, C. R., Zohar, A. H., Hirschmann, S., & Dahan, D. (2012). The psychological costs an d benefits of being highly persistent: Per- sonality profiles distinguish mood disorders from anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136, 758-766. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.046 Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Con- way, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9, 361-368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0015952 Cole, S. W., Arevalo, J. M., Takahash i, R., Sloan, E. K., Lutgend orf, S. K., Sood, A. K., & Seeman, T. E. (2010). Computational identifica- tion of gene-social environment interaction at the human IL6 locus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 5681-5686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911515107 Denollet, J. (2005). DS14 : Standard assessment of n egative affectivity, social inhibition, and type D personality. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 89-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49 Drabant, E. M., Kuo, J. R., Ramel, W., Blechert, J., Edge, M. D., Cooper, J. R., Goldin , P. R., Hariri, A. R., & Gro ss, J. J. (2011). Ex- periential, autonomic, and n eural re sponses during threat anticip ation vary as a function of threat intensity and neuroticism, Neuroimage, 55, 401-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.040 Edmonds, G. W. (2011). Personality and the healthy li festyle (HLS) as predictor of physical hea lth: Can the HLS b e explained by per sona li- ty? Doctoral Dissertation, Champaign: University of Illinois at Ur- bana. Etzion, D., & La ski, S. (1998). The big five inventory (version 5a). Tel- Aviv: Tel-Aviv University. Fredrickson, B. L. & Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist, 60, 678-686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678 Grant, C. C., Vilijoen, M., van Rensburg, D. C., & Wo od, P. S. (2012). HRV assessment of the effect of training on autonomic cardiac con- trol. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 17, 219-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-474X.2012.00511.x Hainsworth, R. (1995). The control and physiological importanceof heart rate. In M. Malik, & A. J. Camm (Eds.), Heart rate va riability (pp. 147-163). Armonk, NY: Futura Publishing Company, Inc. Hintsanen, M., Pulkki-Råback, L., Juonala, M., Viikari, J. S., Raitakari, O. T., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2009). Cloninger’s temperament traits and preclinical atherosclerosis: The cardiovascular risk in young Finns study . Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 67, 77-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.002 Hiramura, H., Uji, M., Sh ikai, N., Ch en, Z. , Matsuo k a, N., Kitamura, T. et al. (2010). Understanding externalizing behavior from children’s personality and parenting characteristics. Psychiatry Research, 175, 142-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2005.07.041 Jarrin, D. C., McGrath, J. J., Giovanniello, S., Porier, P., & Lambert, M. (2012). Measurement f idelity of HRV signal proces sing: The devil is in the details. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 86, 88-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.07.004 Josefsson, K., Jokela, M., Cloninger, C. R., Hintsanen, M., Salo, J., Hinsta, T., Pulkki-Rabak, L., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2013a). Maturity and change in personality: Developmental trends of tempe- rament and character in adulthood. Development and Psychopathol- ogy, 25, 713-727. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000126 Josefsson, K., Jokela, M., Hintsanen, M., Cloninger, C. R., Pulkki- Rabak, L., Merjonen, P ., Hutri-Kahonen, N., & Keltikan gas-Järvinen, L. (2013b). Parental care-giving and home environment predicting offspring’s temperament and character traits after 18 years. Psychia- try Research. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.01.007iU Kawachi, I., Sparrow, D., Vokonas, P. S., & Weiss, S. T. (1995). De- creased heart rate variability in men with phobic anxiety (data from the normative aging study). American Journal of Cardiology, 75, 882-885. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80680-8U Koelsch, S., Enge, J., & Jentschke, S. (2012). Cardiac signatures of personality. PLOS ONE, 7, 1-9. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031441U Kwako, L. E., Noll, J. G., Putnam, F. W., & Trickett, P. K. (2010). Childhood sexual abuse and attachment: An intergenerational pers- pective. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15, 407-422. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359104510367590U Lodi-Smith, J., Jacks on, J., B ogg, T., Walton , K., Wo od, D., Harms, P ., & Roberts, B. W. (2010). Mechanisms of health: Education and health-related behaviours partially mediate the relationship between Conscientiousness and self-reported physical health. Psychology and Health, 25, 305-319. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870440902736964U Matsuoka, O., Otsuka, K., Murakami, S., Hotta, N., Yamanaka, G., Kubo, T., Y amanaka, M., Shinagawa, M., Nunoda, S., Nishimura, Y., Shibita, K., Saitoh, H., Nishinaga, M., Ishine, M., Wada, T., Oku- miya, K., Matsubayashi, K., Yano, S., Ishihara, K., Cornelissen G., Halberg, F., & Ozawa, T. (2005). Arterial stiffness independently predicts CVE in an elderly community—Longitudinal investigation for the LILAC study. Biomedical Pharmacotherapy, 59, S40-S44. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0753-3322(05)80008-3U McCraty, R. , & A tkinson, M. (1996). Autonomic assessment report: A comprehensive heart rate variability analysis. In R. McCraty (ed.), Heart ma th research center reports. Boulder Creek, CA: In stitute of  A. H. ZOHAR ET AL. Open Access Heart Math. McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Lipsenthal, L., & Arguelles, L. (2009). New hope for correctional officers: An innovative program for re- ducing stress and health risks. Applied Psychophysiological Bio- feedback, 34, 251-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10484-009-9087-0 McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tomasino, D., Goelitz, J., & Mayrovitz, H. N. (1999). The i mpact of an e motional self-management skills course on psychosocial functioning and autonomic recovery to stress in middle school children. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Sciences, 34, 246-268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02688693 Miller, G. E., Chen, E., & Parker, K. J. (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptib ility to the c h ron ic d iseases of ag in g: Mo vin g toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psycho- logical Bulletin, 137, 939-997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024768 Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES -D scale: A self-report depressio n scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Mea- surement, 1, 385-401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306 Raynor, D. A., & Levine, H. (2009). Associations between the five- factor model of perso nality and health behaviors among college stu- dents. Journal of American College Health, 58, 73-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JACH.58.1.73-82 Rosenström, T., Jokela, M., Cloninger, C. R., Hintsanen, M., Juonala, M., Raitakari, O., Viikari, J., & Keltikan gas-Järvinen, L. (20 12). As- sociations between di mensional personality measures and preclinical atherosclerosis: The cardiovascu lar risk in Young Finns study. Jour- nal of Psychosomatic Research, 72, 336-343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.02.003 Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (1996). Measurement error in psycho- logical research: Lessons from 26 research scenarios. Psychological Methods, 1, 199-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.199 Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Par k, N., & Peterso n, C . (2005 ). Posi- tive psychology prog ress: Empirical validation of intervention s. Am- erican Psychologist, 60, 410-421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410 Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessin g the presence of an d search for mean- ing in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 Surtees, P. G., Wainwright, N. W. J., Pooley, K., A., Luben, R. N., Khaw, K.-T, Easton, D. F., & Dunning, A. M. (2011). Life stress, emotional health, and mean telomere length in the EPIC—Norfolk population. Journal of Gerontology, 66A, 1152-1162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glr112 Task force of the European So ciety of Cardiology, & The North A mer- ican Society of Pacin g Electrophysiology (1996). HRV, s tandards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Euro- pean Heart Journa l, 17, 354-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014868 Thayer, J. F., A hs, F., Fredrik son, M., Sollers III, J. J., & Wager, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of HRV and neu roimaging studies: Implica- tions for HRV as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36, 747-756. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009 Uliaszek, A. A., Zinbarg, R. E., Min eka, S., Craske, M . C., Griffith, J. W., Sutton, J. M., Epstein, A., & Hammen , C. (2012 ). A longitudinal examination of stress gen eration in depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 4-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0025835 van de Bree, M. B. M., Przybeck, T. R., & Cloninger, C. R. (2006). Diet and personality: Associations in a population-based sample. Appetite, 46, 177-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2005.12.004 van Zuiden, M., K avelaars, A., Rademaker, A . R., Vermetten, E., Heij- nen, C. J., & Geuze, E. (2011). A prospective study on personality and the cortisol awakening response to predict posttraumatic stress symptoms in response to military deplo yment. Journal of Psychiatr ic Research, 45, 713-719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.11.013 Voss, A. (2007). Lon gitudinal analysis of HRV. Journal of Electroca r- diology, 40, 826-829. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.10.024 Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Malinckrod t, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The experience in close relationship ECR-short form: Reliability, valid- ity, and factor structure. Journ al of Personality Assessmen t, 88, 187- 204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223890701268041 Zohar, A. H., & Cloninger C. R. (2011). The psychometric properties of the TCI-140 in Hebrew. European Journal of Psychological As- sessment, 27, 73-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000046 Zohar, A. H., Denollet, J. K., Lev-Ari, L., & Cloninger, C. R. (2011). The psychometric properties of the DS14 in Hebrew and the preva- lence of type D in Israeli adults. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27, 274-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000074

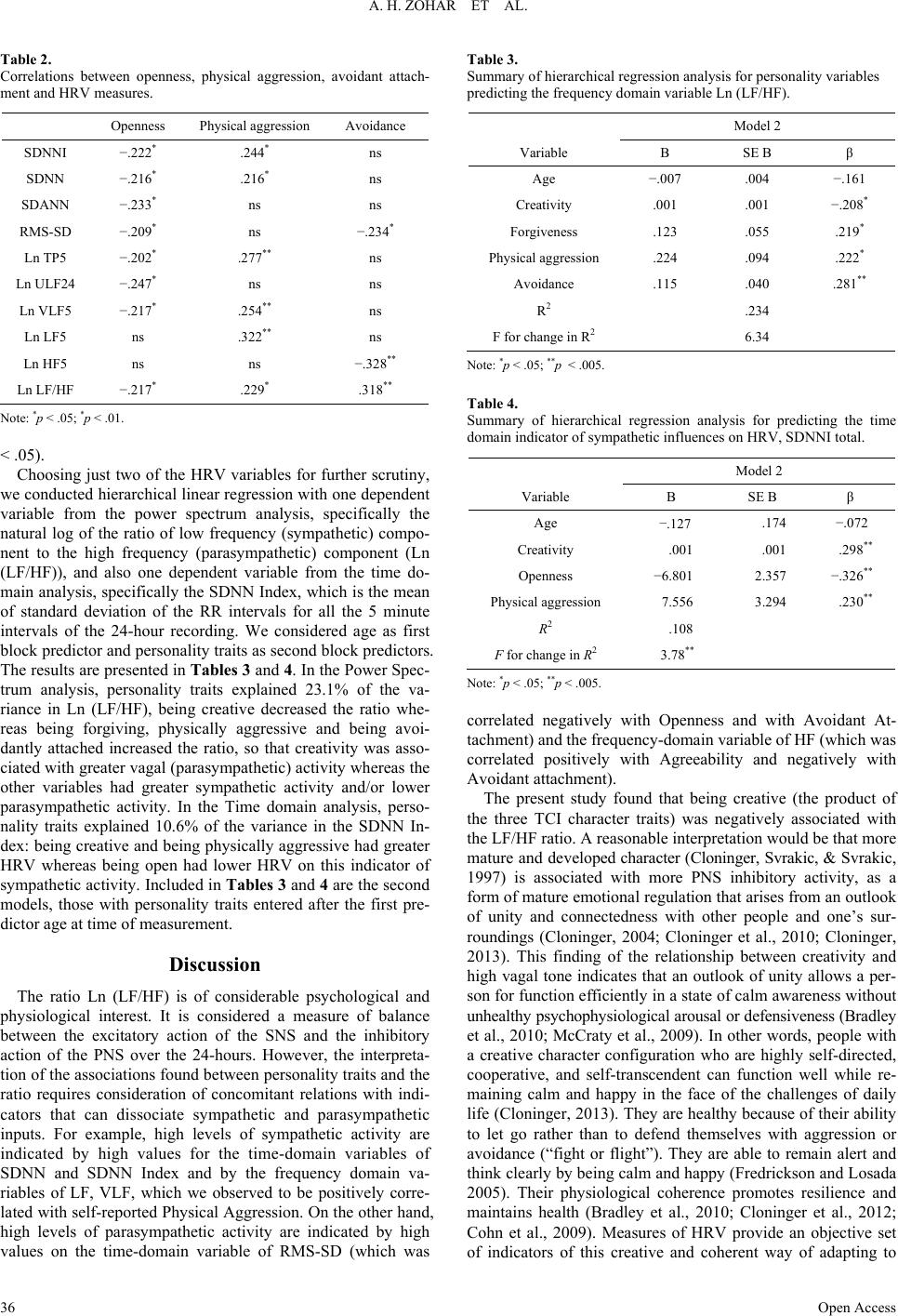

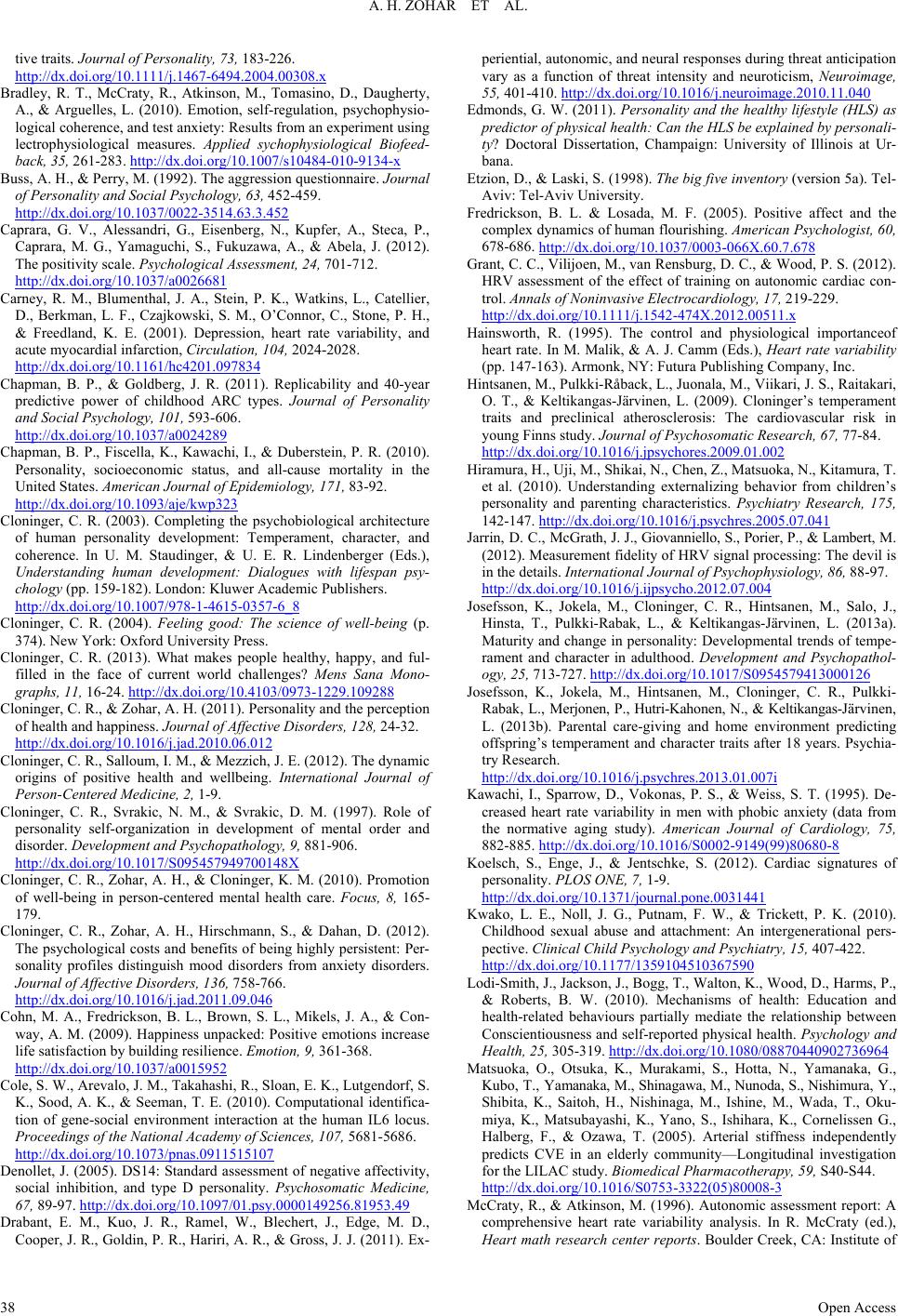

|