Open Journal of Nursing, 2013, 3, 503-515 OJN http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2013.37069 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojn/) Responding to introverted and shy students: Best practice guidelines for educators and advisors Marian Condon, Lisa Ruth-Sahd York College of Pennsylvania, York, USA Email: lsahd@ycp.edu Received 2 July 213; revised 1 October 2013; accepted 22 November 2013 Copyright © 2013 Marian Condon, Lisa Ruth-Sahd. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribu- tion License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Experienced classroom educators are familiar with students commonly thought of as introverted or shy— the noticeably quiet students who are reluctant to speak in class, and generally shun the spotlight. Ma ny educators find such students perplexing and frus- trating because they rarely raise their hands in class, or engage in conversation afterward. It is difficult for educators to discern whether they are reaching such students or whether they are engaged or bored. In- troverted students differ from their more extroverted peers in terms of information processing, classroom behavior, and preferences regarding assignments and activities. As educators, we often ask ourselves whe- ther we are doing all we can, as educators and advis- ers, to foster such students’ learning and personal development, and this question is highly relevant in contemporary education. Introverts are thought to comprise approximately 40 percent of the student body. In addition, cultural background may foster behaviors similar to those observed in shy and/or in- troverted individuals. In this article, introversion, extroversion and shyness are compared and contrast- ed conceptually, as well as in terms of related social and academic behaviors and processes. The questions of whether introversion and shyness confer problem- atic traits, whether students should be helped to over- come or signature strengths, and whether they might be guided to develop further, are also addressed. Best practice guidelines intended to help nurse-faculty re- spond more helpfully to quiet students as educators and advisors are offered. Keywords: Introversion; Extroversion; Shyness 1. INTRODUCTION According to a study by Schaubhut & Thompson [1], including over 100,000 students enrolled in 75 different majors at institutions of higher learning, the majority of college majors have equal numbers of introverted and extroverted students. This result is congruent with a sur- vey conducted between 2007 and 2010, by researchers at the Center for Applications of Psychological Type (CAPT) who found that 40.6% of the college students sampled were introverts (L. Abbitt, Librarian at CAPT, Nov. 4, 2012 telephone communication). Pannapacker [2] sug- gests that this estimate may be low because of the cul- tural stigma attached to introversion and consequently, some students are unwilling to admit, even confidentially, preferences such as staying home and reading in lieu of attending a social event. Introversion and shyness can affect students’ social life on campus and influence strongly the ways in which students prefer to receive and process information in the classroom [3]. There is no question that introversion confers valuable strengths: introverts tend to be better than extroverts at thinking before they act, taking in and processing information thoroughly, remaining on task, and working more accurately. Their non-combative na- ture and willingness to listen make them easy to get along with. According to Cain [4], introverted students’ biggest challenge may be recognizing, acknowledging and making use of their own gifts. Introverts sometimes try so hard to appear more extroverted that they exhaust themselves, undervalue their own talents and allow themselves to be intimidated by the louder, more forceful extroverts in the classroom. Shyness, on the other hand, does not seem to confer any benefit, at least in the dominant American culture. Shyness is a painful trait that can inhibit social interac- tion and the public demonstration of competencies. Shy individuals have been found to have lower self-esteem than comparable individuals who are not shy, and are more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety [5]. According to CAPT’s most recent survey, introverts and OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 504 extroverts are about equally represented among the pro- fessoriate as well with extroverts at 52.8% and introverts at 49.6% (L. Abbitt, Research Librarian at CAPT, e-mail communication). Therefore, providing a balanced mix of introvert-friendly and extrovert-friendly teaching and learning modalities seems to be fair to all concerned as that strategy allows the professor, as well as the intro- verted and extroverted students, to have their preferences honored approximately half the time. However, students who are highly introverted and/or shy will find class- room activities and assignments requiring extroverting behaviors unpleasant and difficult. Thus, the question arises of whether or to what degree it is in those students’ best interest for faculty to compel them to participate in, and be graded on exercises for which they are constitu- tionally ill-suited. Should faculty allow quiet students to opt out of all or some of the activities and assignments that require extroverting behavior? Should they penalize quiet students for appearing nervous and ill at ease while presenting? 2. LITERATURE REVIEW A paucity of resources on how best to deal with intro- verted and shy students was noted in the nursing litera- ture. Searches in CINAHL (introspection), MEDLINE (introversion) and ERIC (introversion, extroversion and shyness) yielded only five articles. Only one was spe- cifically related to nursing education and that was in Taiwan [6], the other four were in journals not specifi- cally related to nursing education. 2.1. Factors that May Underlie Quiet, Reticent Behaviors Quiet, reticent behavior may be related to introversion, shyness, ethnic background, or some combination of the three. While introversion and shyness are often con- founded, they are distinct from one another conceptually and in terms of behavior. 2.1.1. Extroversion/Introversion In the early 1920s psychologist Carl Jung [7] published his theory of human personality. He used the term Psy- chological Type to refer to the relative degree to which individuals possess what he referred to as extraverted and introverted attitudes. Jung defined extroversion and introversion in terms of two central processes: directing attention and deriving personal energy. Jung used the term extroversion to refer to the dual processes of focus- ing on, and deriving energy from the outer world (out- ward orientation), and the term introversion to refer to the process of focusing on and drawing energy from in- ner psychic activity (inner orientation). Thus, for Jung, extroverts are relatively more focused on the activities and things in the world around them than on their interior lives. Introverts, in contrast, are contemplative and self- reflective. Their energy is drained, rather than replenish- ed, by the outside world. Extroversion/introversion (also written extraversion/ intraversion) is identified in the psychological literature as a highly important dimension of human personality that imposes physiological limits on who we are and how we act, although within those limits, behavior can vary according to circumstance. A given person’s degree of extroversion or introversion influences a surprising num- ber of aspects of how that individual thinks, feels and interacts with the world at large [8]. Psychometric tests, e.g. the Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and the Revised Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) are used to determine whether an individual is extroverted or intro- verted, and to what extent. Other theorists have elaborated on, and in some cases, departed somewhat from Jung’s theory [7]. For example, Isobel Myers [9,10], who developed the MBTI, concep- tualized extraversion and introversion as polar opposites on a continuum, as opposed to Jung’s discrete but op- posing qualities. McCrae and Costa [11], who included extroversion in their Five Factor (openness, conscien- tiousness, extroversion, anxiety and neuroticism) model of human personality, defined introversion as the relative absence of traits such as sociability and assertiveness rather than as inner-directedness. The term reflective has been used to describe the learning styles of which intro- version is a component [12]. Table 1 highlights some core differences between introverts and extroverts. While Type is obvious in highly-introverted and highly extro- verted people, it is not always so in slightly introverted individuals or in those who possess an approximately equal number of introverted and extroverted characteris- tics (ambiversion). Another factor is that introverts may deliberately attempt to appear to be extroverted because the characteristics associated with extroversion are val- ued highly in contemporary Western culture [13]. 2.1.2. Shyness Shyness, which can range from bashful timidity and/or wary watchfulness to social avoidance, bears some simi- larity to introversion in that it, too, can give rise to reti- cent behavior. Shy students have difficulty with small talk, are slow to share their feelings and typically do not reciprocate when feelings are disclosed by others [14]. However, shyness, also known as behavioral inhibition and anxious temperament, is a distinct personality con- struct that differs from introversion in some important ways, one being motivation. While a shy student and an introvert might both remain on the sidelines during a class activity, they would have different reasons for do- ing so: the shy person might well want to interact Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 505 OPEN ACCESS more, but would be prevented from doing so by fear of social disapproval, while the introvert would be limiting her social interaction out of preference—because she does not enjoy social interaction with strangers, and is attempting to conserve energy. Unlike introversion, shy- ness is rooted in social anxiety, which is defined as a “··· fretful disquiet that stems from the prospect of negative evaluations from others [15]”. Shy individuals see them- selves as somehow personally deficient, which leads to feelings of self-blame and shame [16]. A key difference between introversion and shyness is that shyness is a painful way of being, while introversion is not. The Re- vised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale [17] is commonly used to measure the degree to which a given individual is shy. More recently, Bortnik, Henderson and Zimbardo [16] devised the Shy Q, an inventory lay persons can use to assess themselves for shy tendencies. Table 2 high- lights some similarities and differences between intro- version and shyness. When shyness causes students to avoid professors and limits speaking up in class, it, like introversion, can compromise academic performance [18]. When shy stu- dents are in an environment, such as a classroom, that arouses their fear of negative evaluation, they may suffer embarrassing manifestations such as blushing, sweating, stammering, shaking hands or knees and even dizziness [19]. Sheldon [20] studied the relationship between un- willingness to communicate and students’ Facebook use and found that shy and introverted students are more likely to use Facebook and other social media to connect with classmates. 2.1.3. Cul tural Backgro un d Quiet, reticent behavior may also be a function of cultur- al background. While the United States is considered to be a highly extroverted nation in comparison with other countries [21,22], its population includes growing num- bers of immigrants from what has been dubbed The Confucian-Belt: China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam [4]. Traditionally, such cultures share collectivist values, i.e. Table 1. Introverts and extroverts. Introverts Extroverts Quiet; reticent Talkative; comfortable in the spotlight Reflective; introspective Active; highly engaged with the outside world Serious Light-hearted Think before speaking Think while speaking Reclusive Gregarious; outgoing Risk-aversive; cautious Bold Uncomfortable with conflict Assertive; dominant Prefer small gatherings with friends Comfortable in larger groups that include strangers Tentative; deliberative Enthusiastic; make quick decisions Drained by the outside world; need to time spend time alone to rechargeEnergized by the outside world; prone to boredom when alone Table 2. Introversion & shyness: Similarities & differences. Introverts Shy People Traits arise from preference Traits arise from low self-esteem & social anxiety Quiet & reticent Quiet & reticent Reclusive Reclusive Reflective & observant Also reflective & observant Good listeners Good listeners Risk-aversive; cautious Risk-aversive; cautious Uncomfortable with conflict Uncomfortable with conflict Need time to think before speaking Need time to think before speaking only if introverted as well as shy Find making small talk with strangers difficult; prefer small gatherings with friends Find making small talk with strangers difficult; prefer small gather- ings with friends. This is doubly true for those who are introverted as well as shy. Feel drained by the outside world. Feel drained by the outside world due to their anxiety about being judged. Shy people who are also introverted have two reasons for experiencing group interactions as draining.  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 506 a given group is considered more important than the in- dividuals who comprise it. Collectivist cultures foster and reward the characteristics associated with introver- sion: studiousness, modesty, abhorrence of the spotlight and reluctance to speak in groups. Silence is seen as connoting seriousness and depth—one speaks only when one has something substantive to say, and only after careful consideration. The student role in traditional Asian culture is to sit quietly and take notes while the professor does all the talking; there is no expectation that students will participate in discussions because students are not seen as learning resources for one another. In contrast, the United States and most European countries share individualistic values; students and wor- kers are expected to distinguish themselves and are rec- ognized and rewarded for doing so. Consequently, new immigrants and second generation Americans who’ve retained traditional Confucian-Belt values are often un- comfortable and at a disadvantage in American schools [23], and later, in American workplaces. Interestingly, Psychological Type has been found to over-ride cultural values. Hutchinson and Gul [24] and Li, Chen and Tsai [6] found that Chinese students who held collectivist beliefs, and thus might be expected to prefer learning in groups if given the chance, preferred group learning only if they had extroverted personalities. If they had introverted personalities, they were averse to group learning in spite of their collectivist values. Con- versely, Type can boost culturally-related preferences. In the same study, extroverted Chinese students who held collectivist views preferred group learning even more than did their extroverted peers who held individualistic views. 2.2. Social Behavior in Introverted and Shy Individuals Introverted and shy individuals’ social behavior tends to differ from that of extroverted individuals in a number of ways that are relevant to educators and advisers. Some of the social behaviors/preferences associated with both introversion and shyness may be seen as weaknesses (both by introverts/shy people themselves and by others) because contemporary American culture embraces what Cain [4] has dubbed the Extrovert Ideal: “··· the omni- present belief that the ideal self is gregarious, alpha, and comfortable in the spotlight”. In comparison with more extroverted students, quiet students tend to be less social, less likely to confide in people they don’t know well and less comfortable with confrontation and conflict. 2.2.1. Soci al i zing Introverted individuals tend to socialize less than extro- verts because they prefer to spend substantial amounts of time alone—reading or online, or just communing with themselves. Although the more introverted a particular individual is, the more solitude she or he is likely to seek, most introverts are not antisocial—they do have friends. Rather than having a number of casual friends, however, introverts typically have only a few close friends with whom they have very meaningful relationships. Some highly introverted individuals may have little or no de- sire for social contact outside their families [4]. Shy peo- ple also tend to socialize less often than extroverts, due to their fears about being judged. The downside to having an introverted and/or shy na- ture is two-fold: being judged unfairly by others and having difficulty making friends. Introverts and shy per- sons are often seen by classmates and educators who don’t understand them as afraid of people, antisocial and socially inept [25]. One of introverts’ strengths, however, is that they make excellent friends; they are good listen- ers and often have a wealth of information—about which they are perfectly willing to speak at length with people whom they trust. Because introverts tend to be highly observant [26], they pay attention to the people and things in their close proximity, and are good at detecting the nuance of various situations. Their heightened aware- ness of the subtleties of social interaction, and their ten- dency to scrutinize carefully allows them to provide val- uable feedback. Shy people possess some of the same strengths as introverts in that they are sensitive to others and make good listeners [4]. 2.2.2. Discl osing Feelings and Knowledge Introverted and shy individuals do not typically disclose their feelings to others unless they know them well, and may not volunteer to share information the way more extroverted people often do. The downside of their re- luctance to disclose their feelings and spontaneously contribute information is that extroverted classmates, educators and faculty advisors may see them as secretive. Also, friends who do not understand introversion/shyness can feel hurt and offended when important developments are not shared promptly, and can begin to doubt the strength and depth of the relationship [4]. 2.2.3. C onfronting Introverts and shy people tend to be uncomfortable with open conflict and consequently avoid it [27]. Thus, if they are dissatisfied with a grade or have an issue with a classmate, they are likely to raise their concern—if they raise it at all—in a relatively muted, non-aggressive way. When confronted by an overtly angry individual, intro- verts and shy folk tend to withdraw or become silent, and may attempt to minimize future contact with that indi- vidual. Extroverts, in contrast, are usually more comfort- able with confrontation, and tend to express their anger more spontaneously and forcefully. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 507 2.3. Introverted and Shy Students in the Classroom Introverted and shy people are also distinct, in their re- spective ways, from extroverts in terms of information processing, preferences regarding assignments and in- class activities, cognitive strengths and what is known as reward sensitivity. 2.3.1. Taking in and Processing Information Introverted students prefer to process information in- wardly, which means they would rather sit quietly in classes and take in and ponder lecture content as opposed to participating in discussions or group learning activities [28]. Such learning should not be misconstrued as pas- sive; reflecting is as much an active process as discussing [29]. Introverts learn via their internal processes, whereas extroverts benefit from having the opportunity to express new learning outwardly, in the form of oral communica- tion. It is common for extroverts to think they’ve mas- tered some element of course content when they have not, and realize their learning is incomplete only after they have attempted unsuccessfully to verbalize the material to another person. Dyadic and small-group work wherein students critique each other’s understanding of material is ideal for extroverted students, but less so for their in- troverted counterparts, who may find fielding unantici- pated, spontaneous questions from peers taxing. Shy students who are extroverted may be prevented by their shyness to discuss course content with other students and professors. Introverted students benefit from in-class and assigned exercises that link interconnecting material; they want to see how a given topic relates to information presented in the course and to real-life application. Introverts are less attracted to new knowledge and need to fit elements of new learning into the big picture; to an introvert, discon- nected chunks constitute only information, not knowl- edge. Introverts benefit from exercises such as summa- rizing, writing critiques, constructing concept maps, si- milarity/difference tables, etc., and tracking progress on projects [12,30]. 2.3.2. Worki ng in Groups In situations such as small and large group discussion, introverts tend to speak up less than extroverts; they pre- fer to listen to what classmates are saying, and need to think about what they might say before they contribute. This is thought to be because whereas extroverts develop their thoughts by drawing upon small amounts of infor- mation stored in their short-term memory, introverts re- call thoughts stored in their long-term memory for the purpose of building more complex associations. Thus, introverts need more time to develop their ideas before they feel comfortable expressing them [31]. Shy students also tend to be silent in groups, but their reticence is due to fear of social judgment. In settings where games or other group activities are taking place, introverts often remain on the sidelines, taking in information and preparing themselves to par- ticipate [25]. Shy students also tend to remain on the perimeter of activities, as a function of their social anxi- ety. Extroverts, in contrast, tend to be outspoken, gre- garious, confident, and quick to join class activities. 2.3.3. Speaking and Presenting in Class Introverted and shy students are typically uncomfortable with being called upon to answer questions in class. Moderately introverted students may be more comfort- able with being called on than shy students, providing they have been forewarned and given adequate time to process their thoughts on the topic. Participating in full-class discussions tends to be unpleasant not only for shy students but for introverts as well, because even if they are familiar with the material to be addressed, dis- cussion involves contributing on the fly, with no time for inner editing. Also, topics can change quickly during discussions and introverts cannot switch their attention from one thing to another as fluidly and easily as extro- verts. Dyadic or small group discussion is preferable for introverted students, particularly if they have had time to bone up on the topic to be addressed and are acquainted with group-mates. Introverted students also do better in groups when they have an assigned task, such as taking notes, keeping track of time, etc. [32,33]. Unfortunately, research done on faculty beliefs about the implications of student behaviors suggests that edu- cators tend to correlate behaviors such as not raising one’s hand in class, not making eye-contact and not in- teracting much with others with lower intelligence and decreased learning potential [34]. A quote from Robert J. Coplan, a shyness researcher in Ottawa, Canada, as noted in Cain [4] sums up the plight of shy and introverted students in contemporary schools and colleges: “Whoever designed the context of the modern class- room was certainly not thinking of the shy or quiet stu- dents. With often-crowded, high-stimulation rooms and a focus on oral performance—the modern classroom is the quiet student’s worst nightmare—if a teacher asks a question and the student doesn’t answer right away, the most common thing is the teacher doesn’t have time to sit and wait, but has to go on to someone else, and in the back of their head might think that student is not as intel- ligent or didn’t do the homework.” Interestingly, and perhaps alarmingly, teacher bias against shy, quiet students is a knife that cuts both ways; students seem to be biased against educators who are less Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 508 than dynamic in the classroom [35]. A study done by Tryon [36] seems to corroborate the importance of fac- ulty animation and enthusiasm to be highly correlated with student satisfaction and perceived degree of learn- ing. When the same professor delivered identical content during two successive semesters, and held the exercises and assignments constant with the only variable being delivery, student evaluations were significantly more positive in the semester during which the professor had been intentionally more animated and enthused. It would seem that introverted educators would be well-advised to manifest, if possible, as extroverted a demeanor in the classroom as they can muster. Happily, some have the ability to do just that; introverts high in a trait known as self-monitoring are adept at extroverting on demand. The self-monitoring trait confers the ability to modify one’s behavior in order to conform to perceived social expecta- tions by gauging accurately what behaviors are appropri- ate in various situations and mimicking others who dis- play the desired behavior. 2.3.4. Writing Written work is an area in which shy and introverted students can really shine, provided they have sufficient mastery of writing skills. Introverts will wish to have time to process their thoughts and polish their work be- fore it is submitted as they prefer to keep rough written work private until they have had time to reflect and per- fect. They may, however, be willing to allow a trusted study partner or friend to provide them with feedback on written projects before they are submitted or presented [37]. Neither introverts nor shy people will appreciate exercises that require them to share extemporaneous in- class writing with either peers or the professor, but may well enjoy sharing their views anonymously, via class- room clicker systems and electronic devices that allow them to choose among options projected on a screen. Introverted and shy individuals are generally more will- ing to disclose their feelings, even to large groups, via electronic media than during face-to-face interactions [38]. Stritzke, Nguyen and Durkin [39], found that stu- dents high in the personality trait openness liked using Internet technologies while students low in openness felt that virtual courses were inferior to the on-campus vari- ety. Overbaugh and Lin [40] found that introverted stu- dents performed better in the online than the lab compo- nent of a course that had both, and that the opposite was true for extroverted students. 2.3.5. Seeking Rewards The term reward sensitivity refers to the degree to which an individual is attracted to and excited by activities and pursuits that seem likely to yield a reward of some kind— a desirable sensation or emotion, a good grade, or a bo- nus or some other symbol of formal recognition. Reward sensitivity may be one of the factors that make extro- verted students relatively more willing to have attention called to them in the classroom. Unfortunately, once aroused by a possible reward, reward-sensitive people are prone to ignoring warning signs that pursuing the reward might be a bad idea, that doing so might be dan- gerous or lead to undesirable consequences. Some theorists, e.g. Cohen, Young, Baek, Kessler and Ranganath [41] see reward sensitivity, rather than an outward orientation, as the actual heart of extroversion— its true defining quality. There is, of course, debate on this point, but, extroverts derive more positive emotion from awards than introverts, and are thus more likely to go out of their way to get them. Introverts pursue re- wards less often than extroverts and seem to be pro- grammed in such a way that their vigilance kicks in as soon as they feel themselves getting excited by the idea of pursuing a reward [42]. Introverts’ ability to resist awards is seen as a strength, as they are less likely to pursue risky ventures themselves, and therefore less likely to lead their organizations into them. 2.3.6. Sol vi ng Problems Introverts’ tendency to think carefully about things may contribute to their ability to excel in what is known as insightful problem solving. When introverted and extro- verted subjects were given printed mazes to negotiate, the introverts spent more time inspecting their mazes and were able to solve more mazes correctly [43]. Extroverts tend to spend less time thinking about problems and situ- ations; they are quicker to take action, and are thus prone to sacrificing accuracy for speed [44]. Introverts also tend to have more perseverance [45,46] when attempting difficult tasks. Introverts outperform extroverts [47] on the Watson-Glaser, a test that appraises critical thinking skills. Extroverts, however, tend to do better than intro- verts on some kinds of cognitive tasks: they are better at multi-tasking, better at handling information overload, and better at working under time and social pressure [48]. Introverts’ superior problem solving ability may ex- plain, at least partially, why they outperform extroverts in high school and in college [49]. Introverts are over- represented in the ranks of National Merit Scholarship finalists and among members of Phi Beta Kappa, and receive disproportionate numbers of graduate degrees [50]. While introverts and extroverts are equally intelli- gent, overall, introversion predicts academic perform- ance better than intelligence quotient [51]. Introverts’ problem solving and critical thinking abilities are definite strengths. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 509 OPEN ACCESS 3. BEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATORS Advising students is a big part of the faculty role and one that often causes stress among faculty who strive to be vigilant in their advising practice. Educators who under- stand the nature of introversion and shyness can make their classroom a safer and more pleasant environment for quiet students without sacrificing the integrity of their courses. They can adjust course requirements, and the manner in which they relate personally to students, so that students can grow without suffering unduly. For best practice guidelines for faculty and faculty advisors see Table 3. 3.1. Making Decisions about Class Participation Almost all the participation-related content in the litera- ture is geared toward helping educators find ways to in- duce reluctant students to participate. While it is true that extroverted skills are still valued highly in many educa- tional settings, the idea that being both highly participa- tory and conversationally adroit is of supreme impor- tance to success in numerous fields of endeavor is being increasingly challenged. Cain [4] attacks the assumption that extroverting be- haviors reap more rewards than introverting behaviors directly and has amassed evidence supporting the virtues and value of less participatory, relatively quiet individu- als. In the book Rethinking Classroom Participation [52], Schultz argues that students’ silence, universally seen by educators as negative, can be conceptualized differently: silence can mean a student is thinking about the concepts being presented, a positive thing, or that a student from a culture in which silence is valued is simply conforming, i.e., behaving in what to him is an appropriate manner. Similarly, silence on the part of introverted or shy stu- dents can be interpreted as a laudatory assertion of per- sonal preference or self-protection, rather than as a sin of omission rooted in weakness. Moreover, there is no cor- relation between students’ propensity for verbal partici- pation and grades [29]. We recommend that faculty weigh these and other considerations when making deci- sions about instructional and evaluative methodology: time allocated to small/large group discussion, whether students who do not participate in discussion will be pe- nalized, whether to assign in-class presentations and whether to permit students to opt out of doing presenta- tions, or choose the manner in which they will partici- pate. 3.2. Responding to Quiet Students Educators who have relinquished their role as Sage on the Stage and embraced student-centered teaching typi- cally allocate classroom time to student activities that involve speaking. As speaking publically tends to make introverted and shy students uncomfortable, faculty must weigh its potential befit against potential harm. There is evidence that quiet students can benefit when professors assist them to at least mitigate their aversion to public discourse through practice. In the online news- letter Faculty Focus [51] titled Shy Students in the Classroom: What Does It Take to Improve Participation? Bart reflected upon her experience as an excellent but shy college student who never participated in class—no matter how familiar she was with the material under dis- cussion—and recounted the ways in which she benefitted when a professor she liked and trusted took her aside, encouraged her to speak up more and enumerated the reasons he thought doing so would be good for her. Over time, with the professor’s support, participating in that class became easier for Bart and she eventually found Table 3. Best practices summary. The following practices related to teaching and advising are recommended for faculty consideration: 1) Accept introversion and shyness as legitimate and normal features of personality. Do not convey disapproval of related behaviors or misinterpret them as evidence of dullness, disinterest, disrespect, etc. 2) Allocate a reasonable portion of class time to introvert/shy person-friendly activities such as listening to lectures, watching videos, reflecting quietly and working on projects individually. 3) Refrain from calling on students randomly, particularly with no advance warning. Consider announcing discussion topics ahead of time. 4) Consider discarding one-size-fits-all constellations of grading criteria in favor of a range of options that allows customization. Collaborate with students in the goal-setting process. 5) Provide students who are attempting to improve their mastery of extroverting behaviors (such as volunteering to answer questions in class and participating in the delivery phase of presentations) with instrumental and emotional support. Take care not to criticize them in front of the class. 6) Where appropriate, consider including basic information about introversion and shyness among the topics addressed in courses. 7) When students confide interpersonal or academic difficulties that may be related to Type or shyness, provide relevant information and apprise them of appropriate campus and on-line resources. 8) When students express dissatisfaction with their major area of study, assist them in considering alternatives, using the procedure suggested by Little (2011) and/or refer them to the Academic Advising Office and/or the Career Counseling Center.  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 510 herself raising her hand even when the professor had not been staring at her encouragingly. Speaking up becomes easier with practice, as illus- trated by an educator [52] who has had experience with trying to land a non-academic job. The following quote illustrates its importance in a circumstance that would no doubt resonate with students: “Being an introvert presents problems for a Real- World job seeker. To the two extroverted career coaches who were making their pitch and evaluating my response, I appeared to be unenthusiastic, even uninterested, in the process. In a job interview, a misunderstanding like that would be fatal to my prospects ···. I was able to take a lesson from that initial encounter: No matter how un- natural it feels, I have to project my energy outward dur- ing the job search [53].” While it can be argued that students benefit from learning to function, to some degree, outside their com- fort zone, mandating spontaneous verbal commentary from students whose intrinsic nature leads them to want to reflect before speaking does not serve them because being more or less forced to speak up can be extremely threatening. Thus, we believe faculty should think twice before they attempt to push resistant students into par- ticipating in discussion, particularly large group discus- sions. Rather, we advocate a more transactional approach; professors should make decisions about how much they will encourage a given individual to speak up in collabo- ration with that individual. College students are, after all, adult learners and may be able to gage, perhaps better than educators, what is best for them. Professors will serve reticent students best by exploring their professional goals with them and helping them weigh the potential benefits of becoming more participatory against the degree to which doing so would be inimical. Faculty must realize that some stu- dents suffer dreadfully when forced to speak in class and that it may well be in their best interests to refrain from doing so. Certainly, faculty should not engage in the practice of posing a question in class, calling immedi- ately upon a selected student, and expecting a coherent and correct answer. The intense discomfort students can experience when ambushed in that manner is described the following quote from the comments section of the Faculty Focus post mentioned above: I hate it when professors call on me ··· my heart races, my face turns bright red, I feel suddenly stupid, and my mind wanders ···. I’ve actually been known to cry when I am forced to answer a question ···. I understand what they are trying to do, but there is no help for this student. I really, can’t say it enough, I appreciate professors who offer other ways of participation such as moodle discus- sion forums, or writing an anonomys [sic.] answer down on a sheet of paper, or anonomys [sic.] white board an- swers. Thanks to the professors who actually care! Paradoxically, it is not only students who may find speaking up in class difficult. Introverted and/or shy educators may find the actual teaching challenging. A professor writing under the pseudonym Benton [30] in the Chronicle of Higher Education recounted his strug- gles with shyness during graduate school and later in the context of his job, and his efforts to ameliorate the plight of the shy students in his classes: “Graduate seminars were particularly painful for me. Sometimes I was so tense that my jaw would hurt by the end of the class. I always wanted to speak, but I also feared looking ignorant compared with other graduate students, who always seemed more confident at express- ing themselves. Every stuttering, incompetent comment I made was a humiliation that I would remember vividly for months ···. I have taught at least 40 classes, but I still find teaching stressful, particularly after the summer break or a sabbatical. As the first day approaches, I’ll begin to worry: Will my voice tremble? Will I sweat profusely? Will I forget my lesson plan? Will I lose their confidence right away? ··· Because of my own struggle with shyness, I recognize that many—perhaps most—of my students suffer from it in one context or another. I don’t see myself as some kind of role model for shy stu- dents, but my experiences help me to understand how any predisposition toward shyness in students is exacer- bated by a highly competitive, critical, or hostile envi- ronment ···. I try to pay attention to the more shy stu- dents and give them low-risk opportunities to speak, even if it’s only one or two words. In all of my courses, I set up online “discussion boards” on which students can post comments and ask questions [29].” The anonymous professor’s post supports our conten- tion that students for whom speaking up in class is truly excruciating should not be forced into it, and demon- strates that faculty have the option of broadening their definition of class participation to include such shy per- son/introvert-friendly [54] activities as using student re- sponse systems (e.g. clickers) in class, contributing to conversations in discussion forums, identifying addi- tional topic-relevant resources for the class, or preparing a written reflections on class activities or content. Shy students are known to spend more time online than non- shy students and to prefer chat and instant messaging over face-to-face communication [50]. Senechal [55] re- commends that educators invite introverted and/or shy students to discuss course topics with them privately, but acknowledges the time-consuming nature of that option. While the occasional student may decide to opt out of all class activities that involve speaking up, many will be willing to stretch themselves if the possible rewards are made clear and they are assured of assistance and support. Such students will benefit from knowing in advance Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 511 what topics will be discussed in a given class and the specific questions they will be expected to address. Because quiet students may well be shy and shy peo- ple are easily embarrassed [15], it is imperative that educators be gentle with students who have relinquished the shore and are braving the swift and unpredictable current of public discourse. The response to an incorrect answer should be an encouraging, almost ··· or you’re getting warm ···, rather than a brusque and censorious no! or wrong! Introverted students, and likely those who are shy and/or highly sensitive, respond more positively to gentle, as opposed to aggressive, mannerisms and lan- guage. Schaeffer [56] found that students who were ex- posed to intimidation over time from faculty in a nursing program tended to suffer actual psychological and physi- ological symptoms, including anxiety, depression, gas- tro-intestinal disease, and mood disorders. There are other strategies professors can use to make it easier for quiet students to speak up more in class. Post- ing discussion topics a day or so ahead of time allows students time to formulate questions and comments in advance. Response rotations can be set up so that on a given day, a certain subset of the students knows it is their day to contribute to discussion; quiet students are more likely to speak in class if they know they are ex- pected to do so [31]. 3.3. Making Decisions about In-Class Presentations In-class presentations are another bane of introverted and shy students, as presenting usually combines group work with being in the spotlight. While we believe really pho- bic, completely unwilling students should be allowed to participate only in the preparation phase of a presentation, or complete an alternate assignment, there is something to be said for the idea that moderately introverted and/or shy individuals benefit from learning how to make a presentation to an audience, as uncomfortable as that might be. Presentation skills are important in a wide range of fields, and many introverts are capable of learn- ing how to extrovert quite effectively, if given opportu- nities to practice. The purpose of requiring students to present, however, should be explained, and reluctant students’ discomfort acknowledged, and treated as a normal and common re- sponse rather than as evidence of some intrinsic defect. Moreover, in nursing courses, which are not typically focused on communication itself, students should be graded solely on content. Their degree of animation, re- laxation, spontaneity, etc., should not affect their grade because the threat of punishment exacerbates communi- cation apprehension, and communication apprehension affects communication skill negatively [57]. Thus, pres- entations should be considered formative exercises, at least in terms of presentation skills. Faculty can foster a positive and supportive classroom environment by modeling compassionate behavior for the class—they can commend nervous presenters’ cour- age and comment publically only on their strengths. Students in general, and introverts/shy people in particu- lar, will benefit from rehearsing their presentations and from anticipating, and preparing for, possible questions from the audience. Even when they decide to participate only in the de- livery phase of a given presentation, introverted or shy students can learn a valuable lesson—that it is possible to share their ideas powerfully without necessarily resorting to means more suited to extroverts [4]. Also, it will bene- fit both quiet and outgoing students to experience the relative ease that comes with playing to their strengths, i.e. pursuing avenues of endeavor to which they are temperamentally suited. Introverts will enjoy, and be good at, gathering and organizing information during the presentation’s assembly phase, while extroverts will rel- ish the opportunity to ham it up during the actual deliv- ery. In school, as in life, many different types of skills are needed to carry out a substantial project of any kind and both introverts and extroverts will benefit from becoming aware of what the opposite type has to offer. It is par- ticularly important that extroverts recognize introverts’ multifaceted strengths and understand that it is a mistake to underestimate or disregard input from relatively quiet people who do not present their views in a forceful man- ner. In a similar vein, one of the most valuable things educators can do for introverted and shy students is to point out and commend their observational and analytical strengths. Quiet students are sometimes so focused on trying to emulate extroverts that they fail to note and appreciate their own gifts [4]. The recommendations above boil down to respect— respect for students as human beings with unique con- stellations of existing knowledge, life experiences, strengths and weaknesses and cultural backgrounds. In- deed, respect seems to be the characteristic students most value in professors. In a survey of over 17,000 undergra- duate and graduate students, Delaney, Johnson, Johnson and Treslan [32] found that respect for faculty was the characteristic most often cited as essential for effective teaching. Educators who customize requirements within the framework of their courses are demonstrating their respect for students as individuals. An added benefit of allowing students to make decisions about how they will learn, and the standards of performance toward which they will strive, is that students will experience, and learn from, the results of their choices [56]. Faculty also bene- fit because they can observe students in the process of analyzing course materials and tackling problems, and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 512 can then use their expertise to intercede as necessary—a creative and fulfilling aspect of the teaching role [3]. 3.4. Allotting Classroom Time for Reflection It has been argued [4,29,55] that contemporary class- rooms are excessively activity-oriented and noisy to the detriment of contemplation, which is preferred by intro- verts and good for extroverts, who may benefit from strengthening their capacity for it. We recommend that during most class sessions, faculty allocate 5 or so min- utes to quiet time during which students can think about material presented in a lecture or film, or a question or issue soon to be discussed. We recommend also that fac- ulty allow students to perform analytical exercises, such as formulating questions, identifying assumptions, com- paring and contrasting, etc., by themselves, instead of in small groups. 4. BEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR ADVISORS Just as approximately half the students in a randomly chosen class are likely to be introverts, half of a given teacher’s advisees will be, also, at least in most majors. Shy students are likely to be well-represented, also. Ad- visors can use their understanding of the implications of introversion and shyness to educate advisees on their way of being and to assist students who are experiencing related social difficulties, academic problems or dissatis- faction with their major program of study. 4.1. Providing Information Simply having their introversion and/or shyness ac- knowledged and accepted as normal by an advisor, and being made aware of potentially useful coping mecha- nisms and resources, will benefit students enormously. The quote below was posted on a website under the nom de guerre “Truculent” (undated) as an answer to the question “What would the world be like if introverts ran it? [53]” “The world will understand us. And our introverted kids won’t go through what we’ve been through because people didn’t understand us. The age of 16 - 20 for me was the worst period of my life (I’m almost 21 now) be- cause of people not understanding me, and I didn’t un- derstand myself also [55].” Advisors can provide students with concise informa- tional handouts on introversion and shyness and on the resources their school has to offer. Most schools have a college and career advising office at which students re- ferred by educators or advisors can take the MBTI and have the implications of their results explained to them. Most schools also have counseling centers that may well provide support groups for students, and individual counseling as needed. 4.2. Assisting Advisees with Social Difficulties Advisors who understand introversion and shyness can be on the alert for student accounts of problems that may be Type-related. For example, in the case of a student who reports that his roommates just don’t seem to like him, it may be that the roommates are extroverts who are interpreting the student’s refusal to accompany them to social events as unfriendliness, and behaving coolly to- ward him in return. Or, an introvert who complains that her roommates are nagging her to go places might be housed with extroverts who are viewing her home-body ways as problematic and believe that she just needs a social nudge ··· or two. Extroverts often believe, mistak- enly, that their introverted friends would be better off if they got out more. Introverted advisees may benefit from information that will allow them to explain their way of being to associates, and from coaching on how to diplo- matically fend off well-meaning extroverts who pressure them to attend unappealing social events. 4.3. Assisting Advisees with Difficulties Related to Academics & Major Area of Study Background noise and certain types of music tend to im- pair introverts’ ability to concentrate more than extro- verts’ [55]. Thus, an introverted student who finds her- self or himself sharing a dorm room with one or more extroverted roommates may soon become embroiled in conflicts over noise level and the general level of activity in the living space. The extroverts may not understand, and thus be unwilling to accommodate, the introvert’s desire for peace and quiet, particularly when trying to study. It would be ideal if all students could be quartered with peers who share their preferences regarding stimu- lation. Although that goal cannot always be met, some colleges’ Residence Life staff does take pains to ensure that students are matched with compatible roommates by considering variables such as cleanliness, when they like to go to sleep, noise level, visitation in the room and oth- er things which may be useful in the felicitous assign- ment of living quarters. Although introverts tend to be good students, assum- ing there are no intervening personal problems or learn- ing disabilities, they may need to be reassured that their desire for lengthy periods of quiet time during which they can study and reflect is not only normal, but advan- tageous to them academically. Both introverted and shy students may have difficulty approaching faculty, in and out of the classroom, and may fail to seek clarification, assistance, etc., when they need it. Advisors can reiterate that educators do want to help, and perhaps provide students with a short teach- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 513 er approaching script they can commit to memory and vary according to the circumstance. Shy students experiencing academic difficulty should be questioned about the amount of time (unrelated to coursework) they spend online. Internet addiction is more prevalent among shy students, who tend to be more comfortable relating online than face-to-face and are known to spend more time online than students who are not shy [38]. 4.4. Assisting Advisees Dissatisfied with Their Major Program of Study It is not uncommon for students to enroll in a selected major, such as Nursing, only to realize it does not suit them. Such realizations should be viewed by advisers as important and commendable discoveries, and trigger a search for the major in which the student has the best chance of finding his or her sweet spot—described by Little [13] as the ideal environment in which to study, work, live and pursue core personal projects. Core per- sonal projects are chosen endeavors that are just right for a given person in that they are meaningful, manageable, not unduly stressful, and supported by others. According to Little, people who are operating in their sweet spot— which, given its optimal nature will provide opportuni- ties to pursue core personal projects—feel more alive and energetic, earn more rewards and enjoy better health, as the stress associated with straining to excel at a pursuit to which one is not well-suited is known to take its toll on body and mind. Little [13] cautions that it can be difficult for introverts to discover their sweet spot because they may well have spent so much of their lives conforming to extroverted norms that ignoring their authentic preferences has be- come reflexive. Advisors can guide students in using the following three processes (recommended by Little) to identify their sweet spot: 1) Thinking back to what they loved to do as a child and what they wanted to be when they grew up, 2) Considering, if the specific childhood aspiration seems untenable, the meaning underlying the choice, e.g., divining what it was about being an explorer that was so attractive, 3) Noting the kinds of work the student gravitates to now, e.g., the types of assignments that are enjoyable or the nature of employment that is or was experienced as fulfilling, and 4) Analyzing the cir- cumstances of those whom the student envies, because we tend to envy those who have what we desire. Advisors may also want to advise introverted students who are considering a given career-focus or job offer within nursing to consider the likely availability of re- storative niches [13]. A restorative niche is a place or circumstance that provides a degree of protection from over-stimulation. Examples include quiet spaces to which one might retire to take a break, having a private office instead of a cubicle in a large space, and having free time on weekends for resting and recharging. Intro- verts should also consider whether a given area of nurs- ing practice will allow them to spend time on activities that suit them, such as reading and strategizing, writing and researching. Academic advisors are not the only sources of assistance for students who become disen- chanted with their major field of study; academic advis- ing center staffs are knowledgeable about all majors. In summary, faculty advisors can assist students who are having social or academic difficulties related to their introversion or shyness by accepting their way of being as normal, providing them with relevant information and directing them to other resources as indicated. 5. CONCLUSION Introversion and shyness are distinct, biologically and environmentally-based personality characteristics that, along with some forms of cultural socialization, can give rise to markedly quiet and reticent behavior in students— behavior that is not widely understood or endorsed in American culture. Students may suffer when behaviors arising from introversion and shyness are misinterpreted by peers and faculty, causing social and academic diffi- culties. Students who are introverted and/or shy are like- ly to prefer teaching and learning modalities that do not require them to speak in class, while their more outgoing peers will prefer activities that involve talking and inter- acting with others. Given that there will be nearly equal numbers of introverted and extroverted students in most classes, and that learning outcomes are better when stu- dents have the opportunity to process new information in their preferred way [12], nurse-faculty may wish to pro- vide a balance of introvert-friendly and extrovert-friend- ly classroom activities and assignments. While there is evidence that some quiet students can improve their abil- ity to speak publicly with practice and support, there is also evidence that for others, speaking up is simply too difficult and painful. Interviewing students who are not speaking in class and allowing them, where indicated, to choose alternate ways of meeting course requirements is an option that allows professors to demonstrate both re- spect and compassion for their students. Gaps in the Nursing Education and the Adult Education literature still exist. More research is needed about how to best maintain a culture of civility and safety in the classroom while meeting the learning needs of a diverse student body. REFERENCES [1] Schaubnut, N.A. and Thompson, R.C. (2008) MBTI type tables for occupations. CPP Inc., Mountain View. [2] Pannapacker, W. (2012) Screening out the introverts. The Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 514 Chronicle of Higher Education, 58, 1-9. [3] Spence, L.D. (2012) Getting over learning styles. http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/learning-styles/getti ng-over-learning-styles/?utm_source=cheetah&utm_medi um=email&utm_campaign=2012.12.07%20Falty%20Foc us%20Alert [4] Cain, S. (2012) Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking. Crown Publishers, New York. [5] Nelson, L.J., Padilla-Walker, L.M., Badger, S., McNa- mara-Barry, C., Carroll, J.S. and Madson, S.D. (2008) Associations between shyness, internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors and relationships during emerg- ing adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 605-615. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9203-5 [6] Li, Y.-S., Chen, P.-S. and Tsai, S.-J. (2008) A compari- son of the learning styles among different nursing pro- grams in Taiwan. Implications for Nursing Education, 28, 70-76. [7] Jung, C. (1971) Psychological types. Collected works of C.G. Jung. Princeton University Press, Princeton. [8] Wilt, J. and Revelle, W. (2009) Extraversion. In: Leary, M. and Hoyle, R., Eds., Handbook of Individual Differ- ences in Social B ehavior, Guilford Press, Guilford, 27-45. [9] Myers, I.B. and Briggs, P. (1980) Gifts differing: Under- standing personality type. Cavies-Black Publishing, Moun- tain View. [10] Myers, I.B. and Briggs, P. (1995) Gifts differing: Under- standing personality type. Cavies-Black Publishing, Moun- tain View. [11] McCrae, R.R. and Costa, P.T. (1990) Personality in adulthood. The Guildford Press, New York. [12] McLeod, S. (2010) Kolb-learning styles inventory. http://www.simplypsychology.org/learning-kolb.html [13] Little, B. (2011) Personal projects and free traits: Person- ality and motivation reconsidered. http://www.brianrlittle.com/articles/bcpersonal-projects-a nd-free-traits/#more-196 [14] Aron, E., Aron, A. and Davies, K.M. (2005) Adult shy- ness: The interaction of temperamental sensitivity and an adverse childhood environment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 181-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271419 [15] Miller, R.S. (2009) Social anxiousness, shyness, and em- barrassability. In: Leary, M.R. and Hoyle, R.H., Eds., Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior, The Guilford Press, New York, 176-191. [16] Bortnik, K., Henderson, L. and Zimbardo, P. (2002) The shy Q, a measure of chronic shyness: Associations with interpersonal motives and interpersonal values. 36th An- nual Conference of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, 14-17 November 2002. http://www.shyness.com/documents/2002/AABTShyQpo sterhandout.pdf [17] Cheek, J.M. (1983) The revised cheek and buss shyness scale. Wellesley College, Wellesley. [18] Ericson, P.M. and Gardner, J.W. (1992) Two longitudinal studies of communication apprehension and its effects on college student’s success. Communication Quarterly, 40, 127-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463379209369828 [19] Purdon, C., Antony, M., Monteiro, S. and Swinson, R.P. (2001) Social anxiety in college students. Journal of An- xiety Disorders, 15, 203-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(01)00059-7 [20] Sheldon, P. (2008) The relationship between unwilling- ness to communicate and students’ facebook use. Journal of Media Psychology, 20, 67-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105.20.2.67 [21] McCrae, R.R. and Terracciano, A. (2005) Personality profiles of culture: Aggregate personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 407-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.407 [22] Sparks, S.D. (2010) Studies highlight classroom plight of quiet students. Education Week, 31, 16-17. [23] Bond, M.H. (1993) Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology. Oxford University Press, New York. [24] Hutchinson, M. and Gul, F.A. (1997) The interactive ef- fects of extroversion/introversion traits and collectivism/ individualism cultural beliefs on student group learning preferences. Journal of Accounting Education, 15, 95-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0748-5751(96)00046-2 [25] Daly, J. (2004) Shying away. http://www.utexas.edu/features/archive/2004/shyness.html [26] Susan (2012) Re: Introvert superpower: observing. http://www.quietlyfabulous.com/2012/09/07/introvert-su perpower-observing/ [27] Opt, S.K. and Offredo, D.A. (2003) Communicator image and Myers-Briggs type-indicator extroversion-introver- sion. The Journal of Psychology, 137, 560-568. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223980309600635 [28] Varela, O.E., Cater, J.J. and Michel, N. (2012) Online learning in management education: An empirical study of the role of personality traits. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 24, 209-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12528-012-9059-x [29] The Master Educator (2007) Teaching students with dif- ferent learning styles. http://www.mastereducatorprogram.com/resources/notes_ learning_styles.html [30] Benton, T.H. (2004) Shyness in academe. The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/article/ShynessAcademe/44632/ [31] Isaacs, T. (2009) Introverted students in the classroom: How to bring them out. http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learni ng/introverted-students-in-the-classroom-how-to-bring-o ut-their-best/ [32] Delaney, J.G., Johnson, A.N., Johnson, T.D. and Treslan, D.L. (2010) Students’ perceptions of effectiveness in higher education. 26th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning, University of Wisconsin. http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/Resource_library /handouts/28251_10H.pdf [33] Wood, C. (2012) Abstract academic: Introverts unite! When it’s convenient, that is. The Signpost, Weber State University. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. Condon, L. Ruth-Sahd / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 503-515 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 515 OPEN ACCESS http://www.wsusignpost.com/2012/09/17/abstract-acade mic-introducing-introversion/ [34] Bosacki, S.L., Coplan, R.J., Rose-Krassner, L. and Hughes, K. (2007) Elementary school teachers’ reflections on shy children in the classroom. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 57, 273-287. [35] Moehl, L. (2011) Exploring the relationship between Myers-Briggs type and instructional perspectives among college faculty across academic disciplines. Mid-west re- search-to-practice conference in adult, continuing, com- munity and extension education. Lindenwood University, St. Charles. http://www.lindenwood.edu/mwr2p/docs/Moehl.pdf [36] Tyron, B. (2005) Lessons for the academic introvert. Chronicle of Higher Education, 52, 2-3. [37] Brookfied, S.D. (2012) Teaching for critical thinking: Tools and techniques for helping students question their assumptions. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. [38] Yeun, C.N. and Lavin, M. (2004) Internet dependence in the collegiate population: The role of shyness. CyberPsy- chology & Behavior, 7, 379-383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2004.7.379 [39] Stritzke, W.G.K., Nguyen, A. and Durkin, K. (2004) Shyness and computer-mediated communications: A self- presentational theory perspective. Media Psychology, 6, 1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0601_1 [40] Overbaugh, R.C. and Lin, S.Y. (2006) Student character- istics, sense of community, and cognitive achievement in web-based and lab-based learning environments. Journal of Research on Technology, 39, 205 [41] Cohen, M.X., Young, J., Baek, J.M., Kessler, C. and Ran- ganath, C. (2005) Individual differences in extraversion and dopamine genetics predict neural reward response. Cognitive Brain Res ea rc h, 25, 851-861. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.09.018 [42] Nettle, D. (2007) Personality: What makes you the way you are. Oxford University Press, New York. [43] Howard, R. and McJillen, M. (1990) Extraversion and performance in the perceptual maze test. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 391-396. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(90)90221-C [44] Berden, L.E., Keane, S.P. and Calkins, S.D. (2008) Tem- perament and externalizing behavior: Social preference and perceived acceptance as protective factors. Develop- mental Psycholo gy, 44, 957-968. [45] Grant, A.M., Gino, F. and Hoffman, D. (2011) Reversing 57: The extraverted leadership advantage: The role of employee productivity. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 528-550. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2011.61968043 [46] Grady, J.S., Karraker, K. and Metzger, A. (2012) Shyness trajectories in slow-to-warm-up infants: Relations with child sex and maternal parenting. Journal of Applied De- velopmental Psyc h ol o gy, 33, 91-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.11.002 [47] Moutafi, J., Furnham, A. and Crump, J. (2003) Demogra- phic and personality predictors of intelligence: A study using the Neo personality inventory and the Myers- Briggs Type Indicator. European Journal of Personality, 17, 79-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/per.471 [48] Murberg, T.A. (2010) The role of personal attributes and social support factors on passive behavior in classroom among secondary school students: A prospective study. Social Psychology of Education, 13, 511-522. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11218-010-9123-1 [49] Furnam, A., Chamorro-Premuzik, T. and McDougal, F. (2002) Personality, cognitive ability, and beliefs about in- telligence as predictors of academic performance. Learn- ing and Individual Differences, 14, 47-64. [50] Harrington, R. and Loffredo, D.A. (2010) MBTI person- ality type and other factors that relate to preference for online versus face to face instruction. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 89-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.11.006 [51] Bart, M. (2011) Shy students in the classroom: What does it take to improve participation? http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learni ng/shy-students-in-the-college-classroom-what-does-it-ta ke-to-improve-participation/ [52] Shultz, K. (2009) Rethinking classroom participation: Listening to silent voices. Teachers College Press, New York. [53] Bainbridge, C. (n.d.) Readers respond: If introverts ran the world. http://giftedkids.about.com/u/ua/glossary/introverted_wor ld.02.htm [54] Stowell, J.R., Oldham, T. and Bennett, D. (2010) Using student response systems (Clickers) to combat students’ conformity and shyness. Teaching of Psychology, 37, 135- 140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00986281003626631 [55] Senechal, D. (2012) Republic of noise: The loss of soli- tude in schools and culture. Rowman & Littlefield Edu- cation, Lanham. [56] Schaeffer, A. (2013) The effects of incivility on nursing education. Open Journal of Nursing, 3, 178-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2013.32023 [57] Roby, D.E. (2009) Educator leadership skills: An analysis of communication apprehension. Education, 129, 608- 614.

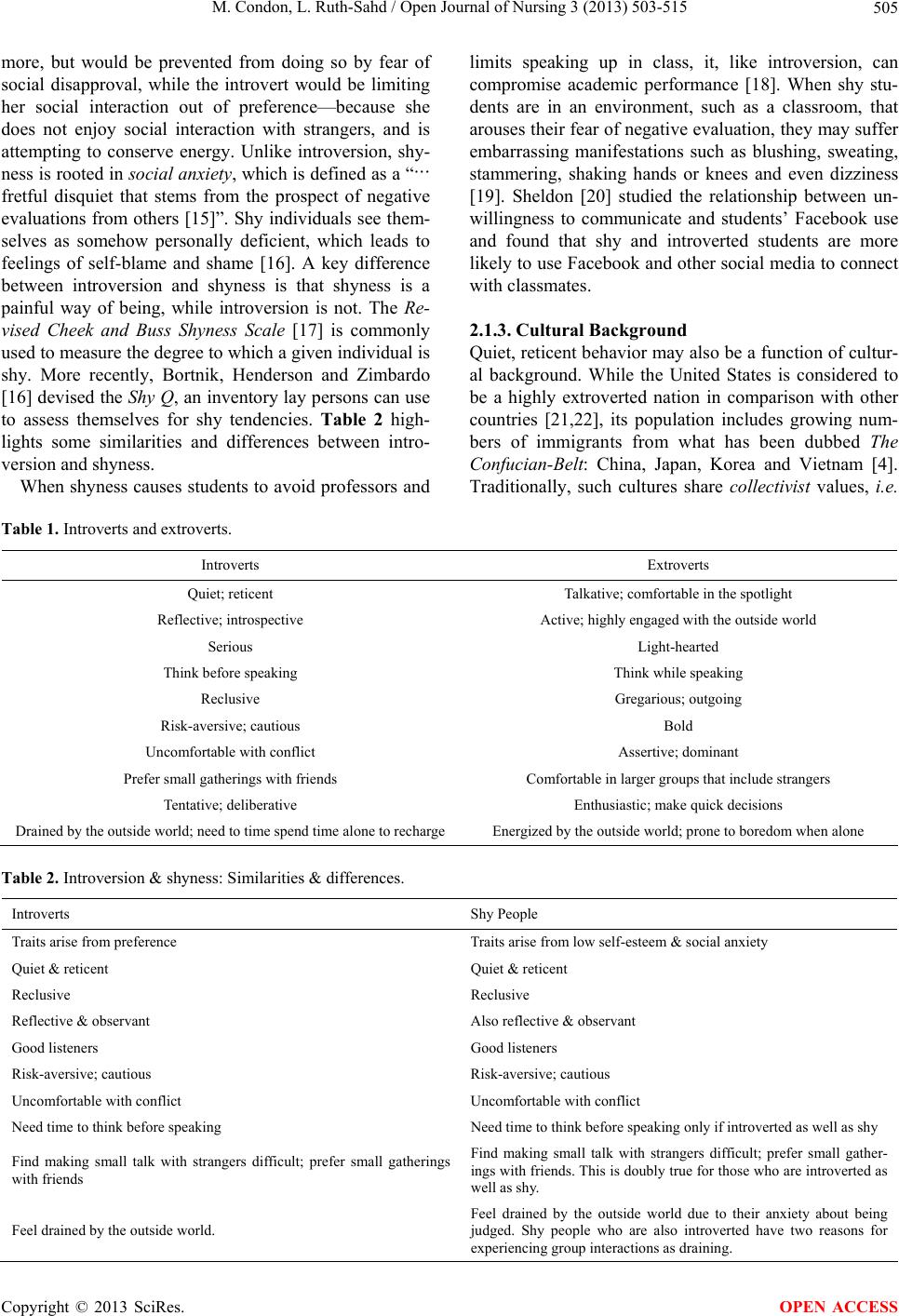

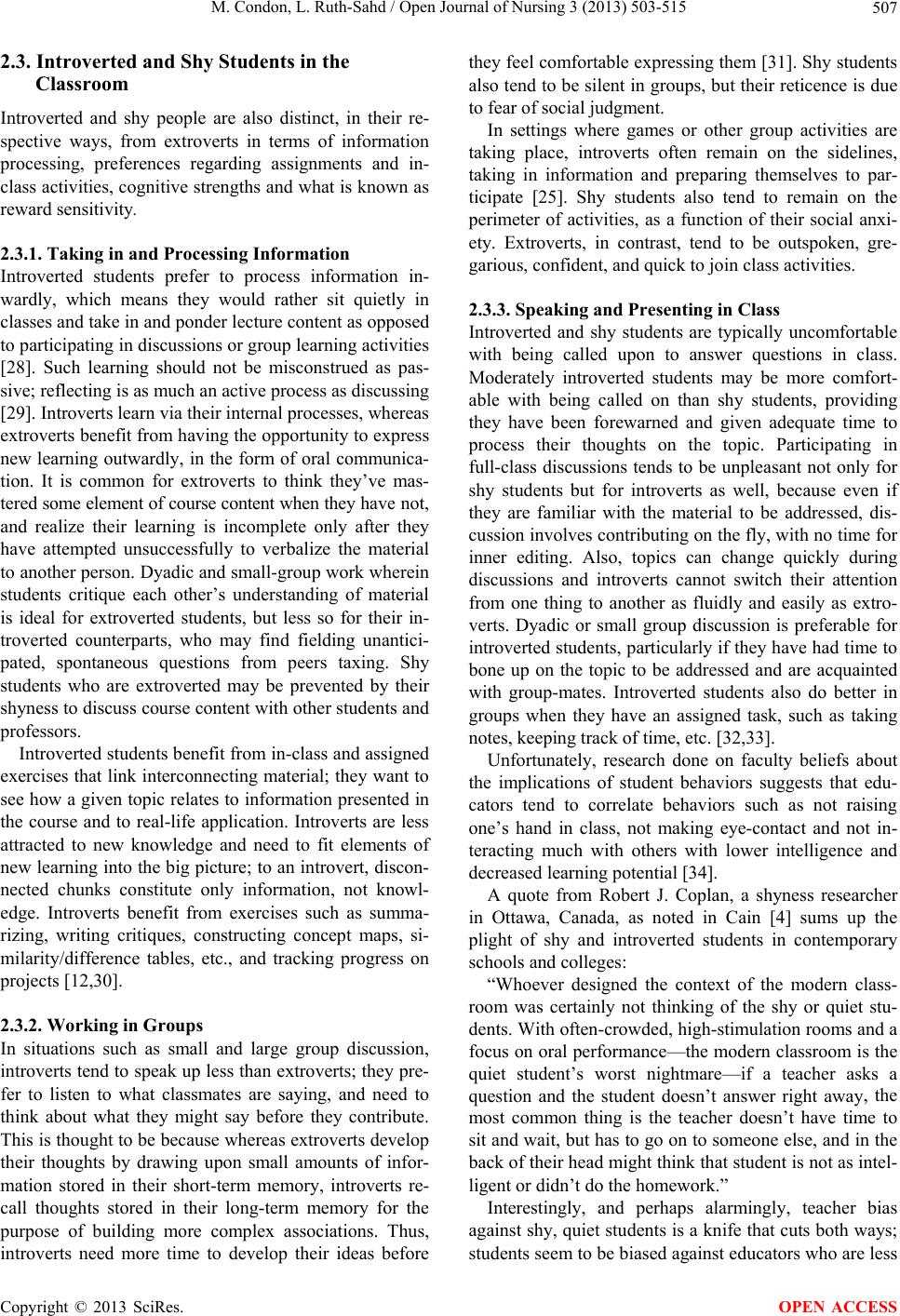

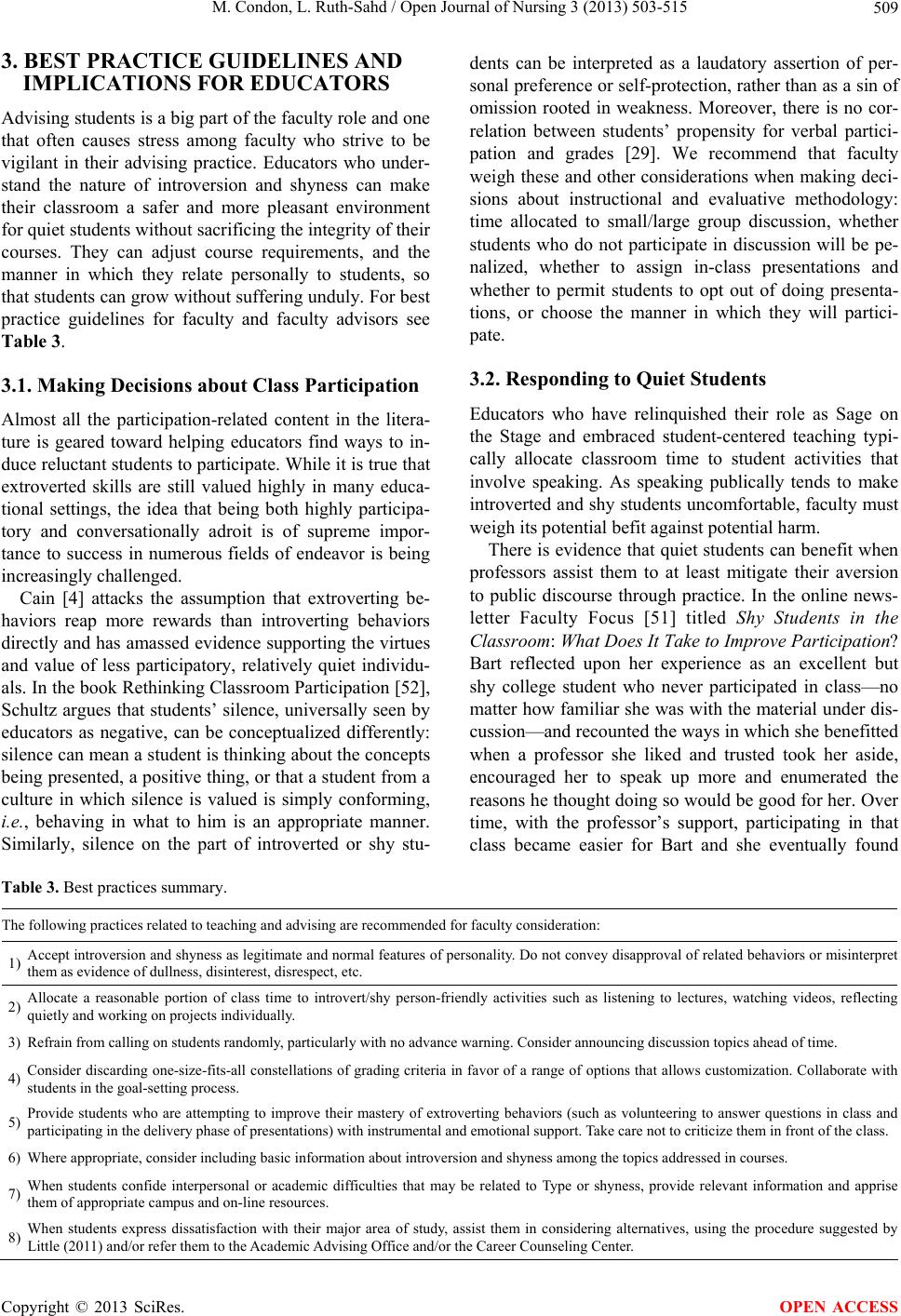

|