iBusiness

Vol.1 No.2(2009), Article ID:1050,10 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2009.12011

Food Safety and the Role of the Government: Implications for CSR Policies in China

![]()

1Associate Professor of International Relations, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia; 2School of Business and Management, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, United States; 3Investment Professional, Fiskiye Sok, Ankara, Turkey; *The Corresponding Author.

Email: rosita_dellios@bond.edu.au, xyang14@usfca.edu, nadirkemal@mac.com

Received September 7, 2009; revised October 8, 2009; accepted November 12, 2009.

Keywords: Corporate Social Responsibility, China, Food Safety, Emerging Market

ABSTRACT

This study investigates food scandals and the role of government in corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the food industry and explores strategies for the Chinese government to tackle the food safety problems that abound in China. Based on the theoretical discussion of four types of CSR and the empirical evidence from four case studies, we argue that government influence on CSR in the food industry is determined by the intensity and salience of its own behavior and actions including regulations. We further believe that a balanced CSR strategy covering economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic considerations would work best for China. Our contributions include extending the CSR literature to the food industry and emerging economies like China and recognizing the distinctive role the government plays in the food industry. In addition, we provide a timely guide to establishing a food safety system in China.

1. Introduction

Food safety is an issue that remains unresolved in both the developed and developing world. Barely having recovered from the shock of “mad cow disease” emanating from the UK in the 1990s, the 2008 “tainted milk” crisis in China serves as a reminder that the problem of food safety has not been contained or adequately addressed. The World Health Organization [1] reports a rise of 30 percent in the number of people in developed countries who become ill from foodborne diseases each year. Smith and Riethmuller [2–4] provide numerous other examples that show foodborne diseases do not discriminate between rich and poor countries with many cases having occurred in Industrialized economies: these range from Japan’s 1996 radish sprouts food poisoning incident that resulted in 10 deaths and 9,000 people being ill, to the “Arnotts Biscuits poisoning, the Australian peanut paste products affected by salmonella bacteria and the Jack in the Box contaminated beef incident in the USA”. So why is food safety still a problem, and a growing problem at that, in the world today?

Apart from the food safety systems still being a “work in progress ” irrespective of which country one wishes to consider [5], Riethmuller and Morison [6] have identified at least three reasons for the growing importance of food safety issues. The first concerns changes in food consumption patterns. People are eating out more, resulting in greater consumer awareness of hygiene. Second, manufactured food products and prepared meals are available through supermarkets and other food outlets, so that the onus is on these food retailers to ensure hygiene standards are adhered to. Third, food safety has become a notable non-tariff barrier in international trade. There are numerous examples of developing nations accusing developed ones of using food safety as a protectionist measure for domestic industry rather than for genuine safety concerns (see, for example, [7,8]).

In view of these global developments the question of who is responsible for food safety arises. As consumers lack the scientific and infrastructural capacity to evaluate food risk, it is incumbent on the food industry to act with both integrity and within the legal guidelines, and for governments to provide those guidelines and enforce them for the consumer’s protection [9].

This article will survey how governments in the United States, the European Union and Australasia regulate the food industry and influence the corporate social responsibility (CSR) behavior of companies—and even the official world of governmental authorities at home and abroad-by examining the relevant characteristics of their food safety systems. We argue that government influence on CSR in the food industry is determined by the intensity and salience of its own behavior and actions including regulations. The case studies have been selected for the purposes of: a) providing exemplars of good and innovative international practice in prevention of food scandals and promoting good practices; and b) showing how national (USA), supranational-plus-international (EU), and bi-national (Australia and New Zealand) authorities handle food safety issues. This is of relevance to China in that it is a unitary state like the USA, but with a policy of strengthening regional cooperation in East and Central Asia (multilateral regionalism) as well as an internal system of provinces and autonomous regions whose collective population size more than doubles that of the EU. The PRC also functions as a “one country, two systems” entity with regard to the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong, Macao and potentially Taiwan that are different to the provinces and autonomous regions within China. The regulatory authority that covers Australia and New Zealand, Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ), provides a successfully functioning model for a regulatory function across two polities. While this “one system, two countries” is the reverse of China’s “one country, two systems” formula, it does show that as the PRC and its Special Administrative Regions continue to converge in terms of a capitalistic system but emphasize politico-social differences within the One China concept, a common regulatory mechanism across various sectors could be an acceptable evolutionary move.

The final section of the article profiles China’s “tainted milk” scandal and draws lessons from the theoretical discussion and case studies for the Chinese government and its food industry. The use of corporate social responsibility as a term applies in China to both private and public sectors as these are often combined, either from the transitional nature of China’s economy (from command to market) or from an emerging trend demonstrated by the EU—the Public Private Partnerships (PPPs). As Howcroft [10] notes:

“Given the scale of the infrastructure and investment gap that the governments of Europe are facing and the constraints that they face in developing and financing their needs, an increased use of PPP approaches is inevitable… [Governments] need to invest in the public sector’s understanding and capability to develop and procure such projects in ways which maximize the overall benefits to the public sector and the public at large.”

In China the boundaries between the state and business are neither clear nor necessarily inevitable. CSR must therefore take a broader view in its purview of application when addressing recommendations for China. Section 2 (What is CSR?), however, will take a theoretical perspective and focus on business enterprises in order to set the stage for conceptual applications for diverse settings and actors (Section 3–Case Studies), from which lessons for China (Section 4) may be drawn.

2. Defining Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate social responsibility varies in meaning and definitions depending on stakeholder perspectives, be they employees, consumers, unions, governments, local communities, shareholders, and executives. Unlike Friedman [11] who poses the conventional argument that an organization’s only responsibility was generating profit, and that any activity that detracted from the goal of profit did not serve the shareholders’ best interests, Carroll [12] goes beyond the economic limits of an organization’s responsibility to add legal, ethical and philanthropic dimensions. Societal rules in the form of laws and regulations had to be followed, but not simply at the minimum required level. Organizations should seek to realize higher standards, thereby fulfilling an ethical responsibility. Moreover, this ethical responsebility feeds into an organization’s philanthropic role of giving back to the community through donating part of its profits to the satisfaction of societal needs generally. Hence, CSR is an encompassing concept covering at least economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic considerations. We argue that a firm’s disposition towards CSR is best understood in terms of whether it fulfils these four types of CSR obligations. For this reason, we will use this encompassing definition of CSR throughout the article.

Governmental influence on the CSR orientation of business firms is well recognized, and there is broad agreement that governments shape the attitude and behavior of company CSR through legislative measures [13–15]. Recently, scholars have noted broader roles that governments have played in promoting CSR [15–19]. Crane and Matten [20] argue that the role of government has changed from traditional regulator of dependent firms to that of multi-faceted player in the face of increased corporate power. We have adopted Fox et al.’s [15] identification of four key roles for governments in promoting CSR: mandating, facilitating, partnering and endorsing. Each of these roles may be expected to vary in intensity and salience in relation to company CSR depending on the types of CSR under study. We believe this definition captures the comprehensive nature of CSR in the food industry. The foremost responsibility of companies engaged in the food industry is not economic profit in preference to all else—for if only profits were at stake then the conesquences could be devastating, as China’s “tainted milk” scandal revealed—but the need to be legally responsible and obey laws.

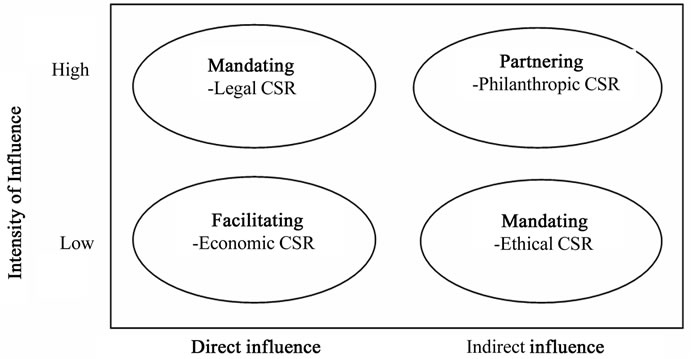

Figure 1. Government Influence on Four Types of CSR.

We agree with Yang and Casali [21] that government influence on CSR is determined by the intensity and salience of its own behavior and actions and have adopted their two-by-two matrix as a framework to illustrate that the interaction between the government’s role and CSR is a function of (direct and indirect) government intervention (see Figure 1).

2.1 Government Influence and CSR

Institutional theories suggest that states develop formal institutions in the form of laws and regulations to effect order, reduce uncertainty, and influence social actor behavior in coordinating and promoting economic exchange [22]. Specifically, rational choice institutionalists argue the behavior and actions of the government are important to the extent that formal and informal rules, with their associated monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms, result in either enabling or constraining social actors [23]. On the other hand, firms may take corrective actions in response or in anticipation of government intervention by choosing to: a) legitimize them, b) avoid legislation, and/or c) avoid negative publicity. Governments, however, can deploy a preemptive strategy to create an institutional environment capable of fostering a CSR outlook in business.

2.2 Governmental Role with Four Types of CSR

2.2.1 Government as Mandator (Legal CSR)

Institutional theory holds that firms tend to comply with government legislation and regulation to legitimize their behavior in the marketplace [22]. Government can wield the power of formal institutions-such as legislation, the judicial system and regulatory agencies-to instill the attitude and shape behavior of company CSR [24]. Government as mandator influences company attitudes to CSR primarily through a carrot-and-stick strategy of: 1) providing tangible inducements for company resource allocation toward stakeholders and behavior that is socially responsible; and 2) inflicting punishment through penalties if actions are not taken, or standards are contravened [21].

Government action in the form of legislation has been argued to be clearly influential in shaping company behavior because it is mandatory [14]. This form of government intervention is direct and its degree can be decisive from the company perspective. Coercion of this nature tends to result in CSR policies being internalized to reduce risks and search costs [25], as evidenced in a high profile US legislative framework-the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002-which legislates financial reporting for publicly traded companies and their auditing firms [26]. A fine of US$5 million and a jail term of 20 years can be the penalty for CEOs and CFOs failing to certify statements or signing false statements [24].

Support is also available for the efficacy of regulation on the emergence of socially responsible behavior with regard to the environment. Stone, Joseph, and Blodgett [27] find that the higher the degree of regulation the greater the likelihood of businesses adopting socially responsible behaviors. The efficacy of government’s role as Mandator is also seen in better compliance with the industry code of conduct [28]. It is argued that one of the motivating reasons for companies to follow codes of conduct appears to be a desire to avoid interference or legislation by government [29–31].

2.2.2 Government as Facilitator (Economic CSR)

Governments can play the role of facilitators to encourage and influence corporations toward being economically responsible. This can be done through government initiatives such as providing guidelines on content, fiscal and financial mechanisms, and creating framework conditions [13]. Notable actions toward facilitation include developing public policies for the training of skilled workers or establishing specialized government agencies to oversee these programs. The UK, for example, implemented Industrial Training Boards and the Manpower Services Commission to encourage CSR in the areas of training and work experience opportunities. Moon [32] found that the Manpower Services Commission led to the Confederation of British Industry forming the Special Programs Unit to ensure large-scale training programs for businesses occurred.

Another mechanism for government as facilitator of economic CSR is provision of subsidies. Government subsidies allow firms to defray costs associated with employment and training schemes, thereby providing greater incentives to participate in new government employment programs [13]. Another example is the UK Department of Trade and Industry’s subsidy of research, publication and a website for BITC reports. In this way, government as facilitator produces the kind of influence that is salient and of direct relevance to the resource capacity of companies to implement economic CSR.

It is common for governments worldwide to sponsor excellence in business awards as a mechanism to encourage economic CSR [32]. Another device is the tax credit designed to bring private enterprise into poorer areas, as shown by the case of the UK 2002 community invest tax credit scheme (ibid.). Businesses are demonstrably more likely to participate in economic CSR programs when the government is seen as Facilitator. For instance, one CSR business association, Business in the Community with its 700 members, accounts for 20% of private sector employment (ibid.).

Also of interest is the finding that governments can exert influence on economic CSR by owning financial institutions, as in the case of the UK [33]. In most cases, government influence on economic CSR is direct, but with low intensity compared to the higher intensity strategy of government as mandator.

2.2.3 Government as Partner (Philanthropic CSR)

Most governments pursue a less regulatory approach in relation to philanthropic responsibility. Rather, they seek to reward good behavior, as shown in the taxation laws of many countries that allow taxpayers to entirely or partially deduct philanthropic donations from their taxable income. For example, the Australian Income Tax Assessment Act of 1997 allows deductions for donations to recognized charities in order to encourage charitable behavior by enterprises. The Australian government benefits through its willingness to partner with business through philanthropy as this strategy spreads the economic burden of social responsibility across both the public and private sectors. Indeed, the popularity of this strategy can be seen through similar approaches taken by some EU countries [13]. According to a 2005 study conducted by the Australian government in collaboration with other organizations, $3.3 billion were given by businesses in Australia between the 2003 and 2004 [34]. These businesses represented 67% of the total number of businesses in Australia (525,900) [34].

Tax deductibility, significant as it is, is not the most important reason for philanthropic behavior in firms. Other positive influences encouraging philanthropic responsibility have been found to embrace the following: a sense of reciprocation, respect for nonprofit organizations, the desire to strengthen the community, and improving the world [34]. In recent years, a phenomenon called “strategic philanthropy” has emerged. Its exponential growth is indicative of its economic value: strategic philanthropy is viewed as a new and innovative way to achieve a competitive advantage. It involves a company directly linking its core business-be it product or service-with charitable activity, for example, by donating one dollar for each purchase of the company’s product, or a percentage of the sales profit for a particular day [35]. In this way, a business can simultaneously fulfill its philanthropic responsibilities, promote its own product or service, and obtain a tax deduction. This provides a strong argument for the efficacy of government as partner when it comes to influencing philanthropic CSR indirectly, albeit very strongly [21].

2.2.4 Government as Endorser (Ethical CSR)

As shown in the Figure 1, the government plays an Endorser role when it exercises its influence indirectly and at low intensity: in other words, when neither legal nor fiscal strategies can be used as influential means in ethical CSR.

Yang and Casali [21]demonstrate that there is a cross linkage between ethics and law, and this nexus reflects the reality of laws issuing from a societal process that identifies and validates collectively the perceived minimum standards in a society, that then become the formal responsibility of government to protect. Arguably, behaviors that have been converted into legislation and then executively reinforced contribute to the pool of societally agreed acceptable standards. These represent in a given era the minimum standards that are not negotiable and must be viewed as core principles [35,36]. The main purpose of the legislative process is to shift those principles from the very least influential government role (Endorser) to the areas where the government can have intensive and direct influence as Mandator, in order to impose those principles on firms in a powerful way. The law-ethics nexus thus represents a crucial space within which governments may manoeuvre to enhance the status and nature of CSR within society’s ontological base.

Yet, government influence may lack power over all those actions that have not yet reached the grey area and that remain more a potentiality or “wish list” than an imperative or “must have list”. Examples of principles in the wish list are: proactive action in environment protection, workplace safety, customer interest, and responsiveness to stakeholder concerns [21].

An example in 2008 of government as endorser was provided by the Prime Minister of Australia, Kevin Rudd, who asked the major Australian banks to pass on interest rate cuts to the consumer in full, emphasizing the fact that this would constitute a more ethical way to do business [37]. Despite political exhortation, there was no supporting legislation, or any tax benefits that would encourage the banks to behave in this way. The government was only endorsing a code of conduct that rested on a key principle: that the main purpose in cutting interest rates should be to reduce the burden of financial pressure on the consumer. It is not intended to increase bank profits by reducing the price of resources (money)—that is, “profiteer at the expense of customers” (ibid.).

The above suggests that government as endorser is in a weak position to influence CSR in terms of intensity and salience as compared to the other three types of CSR. It may be hypothesized that government as mandator is the strongest, with the other two-government as facilitator and government as partner occupying a second tier of intensity and salience. Government as endorser occupies the bottom tier. All, however, are valuable when deployed in concert so as to produce a balanced outcome: too much of one, such as government as mandator, might lead to the “nanny state” syndrome for instance; or an over-emphasis on low-intensity indirect influence could result in an ineffectual CSR effort.

3. Case Studies: The US, the EU, Australia and New Zealand

To understand how China’s food safety system may benefit from the theoretical-analytical discussion above, it is important to now turn to a number of empirical case studies in the developed world where international best practice may be expected to be found. The Chinese themselves have recognized that they lag behind in international norms and practices. At the Fifth China Food Safety Annual Meeting in 2007, China’s Vice Minister of Health Chen Xiaohong admitted that food safety in China did not match that of the developed world. Among the problems he identified were: pollution; low quality of some food products; inadequate technology, equipment, and quality testing systems; as well as weaknesses in food safety management [38].

So what do the experiences of governments in industrialized nations reveal in relation to the hypothesized governmental role with the four types of CSR? What lessons do these findings have for China? The first is a brief case study from the United States where new comprehensive methods are used. The second derives from the European Union whose legislative strengths are especially pertinent to China’s own regulatory instincts, and the final investigation turns to Australia and New Zealand.

3.1 The United States: Comprehensive Strategies in a Unitary State

The Food Protection Plan (FPP), released by the US Food and Drug Administration in November 2007, represents an especially exemplary and up-to-date model in its dual features. These are its provision of: a) an integrated strategy that incorporates “both food safety and food defense for domestic and imported products”; and b) collaborative engagement “across the agency to address the three core elements of protection: prevention, intervention and response” [39]. It is in these collaborative engagements that the government’s role as Mandator, Facilitator, Partner and Endorser in the specific area of food safety becomes evident—not only with the private sector but with all stakeholders.

Admittedly, it can only be judged by the short timeframe of its existence. Still, an overview of the first six months of its activities is available. In terms of prevention, outreach activities are prominent and these approximate the government as facilitator and partner models:

“This outreach has involved multiple meetings with various foreign countries, state and local organizations, and industry and consumer groups… Specific risk-based prevention activities include FDA working in collaboration with states, universities and industry on a Tomato Safety Initiative. In an effort to increase foreign capacity and FDA’s presence beyond our borders, FDA has engaged with India and begun implementation of the China Memorandum of Agreement. The first bilateral meeting with China was held in Beijing in March 2008” [39].

The second core element of protection, intervention, has seen an increase in the number of state inspections and employees to conduct them. Here is a case of government as mandator. The legal regulatory element is evident but it is balanced by qualitative improvements in identifying “food safety threats at the border”; for example, the piloting of a new system called PREDICT. To coordinate developments such as these a research committee has been tasked with maintaining a “collaborative research agenda that supports activities under prevention, intervention and response, such as mitigation strategies and rapid detection systems” [39].

The third pillar of protection is response. Herein lies the government as endorser role, for the key group identified for improved response is that of stakeholders. It is they who are deemed to “be able to quickly identify where a contaminated product came from and where it has been distributed”. Under development is so-called Incident Command System training and Rapid Response Teams “to enable rapid, localized response to incidents” [39].

3.2 The European Union: Codifier and Governance Coordinator

Europe provides a ready laboratory for recent food scandals and governmental responses. In June 1999, it was found that egg, pork, veal, beef, milk, cheese and butter products in Belgium were contaminated with dioxin. The owners of the Belgian company, where the problem was first traced, were suspected of knowingly fabricating or buying from Dutch suppliers feed grain mixed with cheap, second-hand oil or fat that turned out to be contaminated with dioxin. The tainted feed was sold to 1,400 producers in Belgium, France and the Netherlands. Authorities of the European Union, based in Brussels, criticized the Belgian government for taking months to inform the EU about the problem once discovered [40]. This case not only highlights the public-private sector relationship in CSR but levels of government-to-government communication and influence. Codex Alimentarius Commission as the highest international body on global food standards represents a higher governance level than government as mandator within the unitary state. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) Codex Alimentarius Commission met in Rome in mid-1999 to respond to the European crisis over dioxin-contaminated animal products. The Commission set up an intergovernmental task force to accelerate the adoption of a Draft Code of Practice on Good Animal Feeding. It also approved the establishment of an intergovernmental task force to speed up the elaboration of guidelines and standards for foods derived from biotechnology; and passed new international guidelines that clearly defined the nature of organic food production to prevent misleading claims. The new guidelines covered the production, processing, labeling, and marketing of organic food [41].

“Mad cow disease” was perhaps the most publicized of the European food scandals in recent time. It was related to the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) and its human form, Creutzfeldt-Jakob (nvCJD) disease. The press release from the FAO on 26 January 2001 warned that the risk of BSE and its human form posed a risk worldwide and not only in Europe. The FAO also noted that all countries which imported cattle or meat and bone meal (MBM) from Western Europe, especially the UK, during and since 1980s, could be considered at risk from the disease [42].

The BSE and nvCJD issue once again showed that food scandals are closely associated with international trade and this is an area in which government as mandator has been less effective than the national level. In the aftermath of the issue, international actors such as FAO and WHO Codex Alimentarius engaged in a study on a “Code of Practice for Good Animal Feeding” to ensure that animal products do not pose health risks to consumers. Consultations were wide-ranging and included the European Union, Australia, Canada and the United States. This is a case suggestive of global governance as endorser to influence national governments to become Mandators of CSR to the food industry, to assist in its task; the FAO introduced an internet based information service that included a rapid alert system on food safety issues [43].

3.2.1 White Paper on Food Safety

In the aftermath of the BSE and dioxin food scandals, the EU published its “White Paper on Food Safety” (12 January 2000). It should be noted that at the time when the EU faced alarming food scandals, the EU was the world’s largest producer of food and beverage products and this industry was the third largest industrial employer of the EU with over 2.6 million employees, of which 30% were in small and medium enterprises [44].

The white paper proposed a “radical new approach” for food safety in Europe. Like the recent US Food Protection Plan, food safety policy would be comprehensive and integrated in its conception. To this end, an independent European food authority was proposed.

3.2.2 Formation of a Food Safety Authority

The Commission stated that an independent European food authority would be entrusted with “scientific advice on all aspects relating to food safety, operation of rapid alert systems, communication and dialogue with consumers on food safety and health issues as well as networking with national agencies and scientific bodies” and it would serve an analytical function but only the European Commission would decide on what action to take. The food authority’s fundamental principles would be independence, excellence and transparency [44]. A wide range of other legislative measures were proposed covering all aspects of food products from “farm to table”. The legislation was aimed to be easily understandable for all operators to put into effect. It gave “teeth” to an otherwise weak government as endorser function. The EU as a supranational government is showing the way forward in terms of governmental influence combining Mandator with Endorser.

Like the American example above, stakeholder values were upheld by the white paper’s proposed actions to keep consumers well informed about newly emerging food safety concerns and to involve them in food safety policy. The white paper also had implications for trade partners of the EU which, in its position as a massive importer and exporter of food products, must play an “active role” in international bodies and be effective in explaining the European position on food safety [44].

The outcomes of the action plan were the integration of food safety policies within the EU countries and—to an extent—the EU’s trade partners, as well as a more coordinated system. Transparency at all levels of food safety policy stands out as a key principle. Relating to BSE legislation, the white paper identified the problem of inconsistency in approach. In addition, the adoption of measures did not involve all EU institutions. In order to address the integration needs within the single market of the EU, a new approach was proposed for farming, food processing, handling and distribution.

As a result of the proposals, the European Food Safety Authority (see website EFSA, 2008a [45]) was set up based on Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council, on 28 January 2002, as an independent source of scientific advice and communication on risks associated with the food chain [46].

The lessons from the EU on government strategies for CSR in the food safety arena are that a combination of the top and bottom tier (legal Mandator and ethical Endorser) works best. The ethical (independence from government, transparency, and stakeholder consultation which are norms that are being entrenched) is in fact subsumed within the legal legislative framework through the EU’s unique governance structure. This is a more codified, yet governance (not government)-based system which sets it apart from nation-states like the US. The EU, however, shares with the US and the bi-national case study below (Australia and New Zealand) the philosophy of a comprehensive and coordinated approach. This pertains to a systems approach where the whole system is examined and activated, rather than selective problem-solving.

3.3 Australia and New Zealand: One System, Two Countries

Integration and collaboration as twin themes of international best practice in food safety are also evident in the antipodes. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) is a bi-national government regulatory agency whose mission, according to its website is “to provide a safe food supply and have well-informed consumers”. Its main responsibility is to develop and administer the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code which is given legal force through these two countries’ food legislation. FSANZ as well as other government agencies “monitor the food supply to ensure that it is safe, and that foods comply with standards for microbiological contaminants, pesticide residue limits and chemical contamination” [47]. At the time of the Chinese “tainted milk” scandal, FSANZ’s website provided updates on Chinese imported food, including products withdrawn, product testing, consumer advice and maximum melamine levels in food. In a coordinated effort with other national and state food safety agencies, FSANZ engaged in the following actions [47]: working with importers and local food manufacturers to ascertain if products with Chinese dairy ingredients are possibly contaminated with melamine; conducting precautionary testing of products on Australian shelves; monitoring of imports by the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service; and working closely with food regulators around the world including the WHO.

The above is indicative of how the Australasian system responds to a food contamination problem when it involves imports. China turned to the WHO for help in its “tainted milk” crisis and more rigorous regulations on food safety were being introduced [48].

The final section of this article draws lessons for China from the foregoing two sections on CSR theory and empirical case studies.

4. Lessons for China

4.1 Background to China’s “Tainted Milk”Scandal

The “tainted milk” scandal broke out in China in September 2008. The Sanlu brand of powdered milk formula was found to be tainted by the industrial chemical melamine, a binding agent used for plastics and glue but added to watered-down milk as it mimics protein. The contamination resulted in the deaths of at least four babies and some 54,000 infants needing medical treatment that month. The main symptom was kidney stones, for which 3,458 infants were hospitalized in Beijing alone; indeed, a survey of 308,000 households in Beijing indicated that a quarter had fed their children the contaminated milk prior to it being removed from the shelves [49]. Melamine was found not only in Sanlu baby formula but a total of 53 dairy brands in China, as well as foreign brands using Chinese dairy ingredients [50]. This was not the first food safety incident emanating from China. A range of goods exported from China, including toothpaste and pet food, have been found to contain melamine and other industrial chemicals.

Premier Wen Jiabao responded to the scandal by saying China had to strengthen monitoring at the production level, as well as instilling a stronger sense of social conscience and business ethics at the management level [51]. So, too, Chinese President Hu Jintao said lessons must be learned from the milk scandal to “ensure all dairy products sold to the market are qualified products” [52]. By late October 2008, a draft food safety law was being considered by the National People’s Congress. The law would seek to a) “prevent any cover-ups by health authorities”—which was said to have occurred in the Sanlu case in order to avoid a scandal during the Beijing Olympics—and b) would confer on these same government health officials direct responsibility for approval of any additives in processed food [49]. Thus the authorities would be held responsible for what goes into processed food as well as for attempts to disguise the outcome.

4.2 Lessons

Besides a lack of proper governmental oversight and inadequate procedural mechanisms in quality testing, the “tainted milk” scandal (like other unsafe products in the past) showed the presence of corrupt business practices that bypassed China’s quality controls. As noted by deGategno [53]: “China has not succeeded in building effective systems for monitoring and enforcing ethical standards among its officials. The central government has and is continuing to implement reforms that make officials increasingly accountable, but they have little control if no one reports corrupt acts.” It is local officials, according to deGategno, who are key players in food safety and who need to abide by the rules. Here is a case of government needing to instill ethical CSR at the level of businesses and local officials. The strategy to do so requires not only an EU-style government as both Mandator and Endorser, but also more work on the government as Facilitator and Partner.

The corruption factor has an international dimension. Ironically, a company from New Zealand—an exemplary country in terms of food standards regulation and business ethics-was involved in the scandal. Owner of 43% of the Chinese company at the centre of the scandal, Sanlu, was New Zealand dairy co-operative Fonterra. It transpired that Fonterra had known of the melamine contamination six weeks before it “raised the alarm” (Sanlu allegedly had known for eight months) [54,55].

The involvement of Fonterra illustrates the global nature of food manufacturing and the wider governance responsibility this entails. The EU provides a quality model for the international dimension of how to codify, facilitate, communicate and develop a normative environment for food safety in cooperation with other governments and stakeholders. China’s own white paper on food safety, published in August 2007, reflects a number of these lessons [56], even if they were to no avail for the victims of the “tainted milk” scandal within a year of its publication. Such was the impact of this scandal that the UN published its own report on food safety in China in October 2008. China needed to modernize its food safety legislation, overcome ambiguities in supervisory responsibilities; improve oversight and enforcement; better educate stakeholders—consumers, the food Industry and health authorities; and continue to pursue international standards of best practice. One of the problems in China was that there were too many small enterprises, many illegal, to monitor. It is these that are thought responsible for introducing illegal chemicals, with melamine having “apparently ended up in dairy products after middle men who collected milk from farmers and sold it to large dairy companies added the chemical” [57]. Approximately 350,000 of China’s 450,000 registered businesses in food production and processing employ as few as 10 people or less. The UN report blamed these small enterprises for presenting “many of the greatest food safety challenges” (ibid.).

Despite the importance of government regulation in the government as mandator strategy, as discussed in this article, on its own it is inadequate and requires the other three types of CSR to combine for greater effectiveness. The Chinese system was found to be antiquated in that it was managed by different regulations and an ethos of government being expected to be responsible for the entire food system, whereas producers also needed to be responsible for food safety [58]. To induce greater responsibility on the part of food producers, the activation of government as facilitator, partner and endorser represents a more comprehensive strategy.

For China, the experiences of others allow it the advantage of being able to leapfrog in the construction of its own food safety system, so that the “workshop of the world” can simultaneously lift standards and glean the best practices the world has to offer on a comparative basis. That China is traveling this path is evident from the decision to publish its own white paper on food safety in 2007 to allay fears about the safety of China’s exports, and other reforms that were underway after the “tainted milk” scandal in 2008. Already China’s Food and Drug Administration has been placed under the Ministry of Health rather than having the responsibility divided among 16 organizations. Moreover, some companies—Sanlu included—which were previously allowed to conduct their own quality inspections are no longer permitted to do so [50]. An attempt to change the government culture of hiding problems to one of reporting them promptly is underway through legal measures but also needs to be strengthened through consumer protecttion mechanisms and an enhanced corporate social responsibility.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that food safety has to be bound with CSR and the government has a critical role to play by developing comprehensive strategies to make corporations in food industry behave in a socially responsible way. A number of contributions emerged from our exploratory study. First, we have extended the CSR literature to the food industry and emerging economies like China. Second, we have identified the distinctive role the government plays in the food industry and that government influence on CSR in the food industry is determined by the intensity and salience of its own behavior and actions. Third, we have provided a timely guide to establishing a food safety system in China based on empirical evidence that a balanced CSR strategy covering at least economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic considerations would work best for China.

REFERENCES

- WHO, WHO Initiative To Estimate The Global Burden Of Foodborne Diseases, 2007, http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/foodborne_disease/FERG_Nov07.pdf.

- Smith, D. and Riethmuller, P., “Consumer concerns about food safety in Australia and Japan,” British Food Journal, Vol. 102, No. 11, pp. 838–855, 2000. (Previously published in the International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 26, No. 6, 1999).

- New York Times, “Japan says radishes caused food,” Poisoning, 1996, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9C02E3D8153EF93BA3575BC0A960958260.

- English, Holly, “Arnott’s doesn’t crumble under pressure,” St. James Ethics Centre, City Ethics, No. 28, 1997, http://www.ethics.org.au/about-ethics/ethics-centre-articles/ethics-subjects/business-ethics/article-0296.html/.

- ChinaCSR.com, UN Issues Paper on Food Safety in China, 2008,http://www.chinacsr.com/en/2008/10/24/3438-un-issues-paper-on-food-safety-in-china/.

- Riethmuller, P. and Morison, J., “A comparative survey of beef consumption behaviour in Australia, Japan and the United States,” Agricultural and Resource Management Services Pty Ltd, 1995.

- Avila, John Lawrence, Non-Tarrif Barriers Facing Philippine Exporters, World Bank, 2005,http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEAPREGTOPINTECOTRA/Resources/579386-1145902243289/Philip pines-John-6-27.pdf.

- Arun, S., Government Asks EU to Lift ‘Paranoid’ Health-Related Trade Barriers, The Financial Express India, 2008, http://www.financialexpress.com/news/Govt-asks-EU-to-lift-paranoid-healthrelated-trade-barriers/307540/0.

- Kennedy, D., “Humans in the chemical decision chain,” In H. O. Cater and C. F. Nuckton, Ed., Chemicals in the human food chain: Sources, options and public policy. University of California, Davis, Agricultural Issues Center, 1988.

- Howcroft and Adrian, Public and Private Sectors: Who’s Learning from Whom? European Business Forum, 2008, http://www.ebfonline.com/Article.aspx?ArticleID=246.

- Friedman, M., “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” New York Times Magazine, 1970.

- Carroll, A. B., “A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 497–505, 1979.

- Albareda, A., Lozano, J. M., Tencati, A., Midttun, A., and Perrini, F., “The changing role of governments in corporate social responsibility: drivers and responses,” Business Ethics, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 347–363, 2008.

- Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., and Ganapathi, J., “Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multi-level theory of social change in organizations,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 836–863, 2007.

- Fox, T., Ward, H., and Howard, B., “Public sector roles in strengthening corporate social responsibility: A baseline study,” World Bank, 2002.

- Aaronson, S. A., “Corporate social responsibility in the global village: The british role model and the American laggard,” Business and Society Review, Vol. 108, No. 3, pp. 309–38, 2003.

- Zappal, G., “Corporate citizenship and the role of government: The public policy case,” Australian Research Paper 4, 2003–2004.

- Lepoutre, J., Dentchev, N., and Hene, A., “On the role of the government in the corporate social responsibility debate,” paper presented at the 3rd Annual Colloquium of the European Academy of Business in Society, Ghent, 2004.

- Nidasio, C., “Implementing CSR on a large scale: The role of government,” paper presented at the 3rd Annual Colloquium of the European Academy of Business in Society, Ghent, 2004.

- Crane, A. and Matten, D., “Business Ethics: A European Perspective—Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization,” Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Yang, X. and Casali, L., “In search of the missing link: An analysis of government influence in CSR,” Sinergie, 2009.

- North, D. C., “Institutions, institutional change, and economic preference,” Norton, 1990.

- Campbell, L. J., “Why should corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 946–967, 2007.

- Yang, X. and Rivers, C., “Cross-border differences in company attitude to corporate social responsibility,” Journal of Business Ethics, DOI 10.1007/s10551-009- 0191-0, September 2009.

- Husted, B. W. and Allen, D. B., “Corporate social responsibility in the multinational enterprise: strategic and institutional approaches,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 37, No. 6, pp. 838–849, 2006.

- Rockness, H. and Rockness, J., “Legislated ethics: From enron to sarbanes-oxley, the impact on corporate America,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 57, pp. 31–54, 2005.

- Stone, G., Joseph, M., and Blodgett, J., “Toward the creation of an eco-oriented corporate culture: A proposed model of internal and external antecedents leading to industrial firm eco-orientation,” Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 68–84, 2004.

- Aguilera, R. V. and Cuervo-Cazurra, A., “Codes of good governance worldwide: What is the trigger?” Organization Studies, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 415–43, 2004.

- Brereton, D., “The role of self-regulation in improving corporate social performance: The case of the mining industry,” in Proceedings the Current issues in regulation: Enforcement and compliance conference, Australian Institute of Criminology, Melbourne, 2002.

- Diller, J., “A social conscience in the global marketplace? Labour dimensions of codes of conduct, social labelling and investor initiatives,” International Labour Review, Vol. 138, No. 2, pp. 99–129, 1999.

- McInnes, D., “Can self-regulation succeed?” Canadian Banker, Vol. 103, No. 2, pp. 30–36, 1996.

- Moon, J., “Government as a driver of corporate social responsibility: The UK in comparative perspective,” ICCSR Research Paper Series 20-2004, ICCSR, University of Nottingham, pp. 11–27, 2004.

- Yamak, S. and Süer, Ö., “State as a stakeholder,” Corporate Governance, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 111-120, 2005.

- Australian Government, Australian Giving: Research on Philanthropy in Australia, 2005, http://www.ag.au/cca.

- Ferrell, O. C, Fraedrick, J., and Ferrell, L., “Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases, 6th,” Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005.

- Trevino, L. K. and Nelson, K. A., “Managing business ethics: Straight talk about how to do it right, 4th,” John Wiley and Sons, 2007.

- Uren, D. and Richard, G., RBA Tells Banks: Pass on Rate Cut, The Australian, 2008, http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,24177884-601,00.html.

- ChinaCSR.com, 300 Chinese Food Companies Pledge To Ensure Food Safety, 2007, http://www.chinacsr.com/en/2007/09/25/1715-300-chinese-food-companies-pledge-to-ensure-food-safety/.

- FDA—US Food and Drug Administration, FDA Food Protection Plan Six-Month Progress Summary, 2008, http://www.fda.gov/oc/initiatives/advance/food/progressreport.html.

- New York Times, Brussels Journal; Food Scandal Adds to Belgium’s Image of Disarray, 1999, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F06E0DC1139F93AA35755C0A96F958260&sec=health&spon=&pagewanted=all.

- FAO, Codex meeting passes new international standards for food safety, 1999, http://www.fao.org/News/990701-e.htm.

- FAO, FAO: Countries Around the World Should be Concerned About ‘Mad Cow Disease’ and should Take Action to Reduce and Prevent Risks, 2001a, http://www.fao.org/waicent/ois/press_ne/PRESSENG/2001/pren0103.htm.

- FAO, FAO/WHO Call for More International Collaboration to Solve Food Safety and Quality Problems, 2001b, http://www.fao.org/WAICENT/OIS/PRESS_NE/PRESSENG/2001/pren0143.htm.

- European Commission (Commission of the European Communities), White Paper on Food Safety, 2000, http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/health_consumer/library/pub/pub

- 06_en.pdf.

- EFSA—European Food Safety Authority, 2008a, http://www.efsa.europa.eu.

- European Commission (Commission of the European Communities), Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety, 2002, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/smartapi/cgi/sga_doc?smartapi!celexapi!prod!CELEXnumdoc&lg=EN&numdoc=32002R0178&model=guichett.

- FSANZ—Food Standards Australia New Zealand, 2008, http://www.foodstandards.gov.au.

- ABC Radio Australia, Head of China’s product quality agency resigns, 2008a, http://www.radioaustralia.net.au/news/stories/200809/s2371425.htm.

- AFP, Quarter of Beijing Kids Fed Bad Milk, The Australian, pp. 10, 2008a.

- Magistad and Kay, M., China’s Image Sullied by Tainted Milk, Yale Global Online, Yale Center for the Study of Globalization, 2008,http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/display.article?id=11403.

- China Economic Net, “Premier vows to provide safe products for people and world,” 2008, http://en.ce.cn/National/Politics/200809/28/t20080928_16950835.shtml.

- Xinhua News Agency, Domestic Service, Beijing, in Chinese, translated by BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific, China: Hu Jintao Inspects Anhui Farms; CCP Third Plenum to Discuss Rural Reform, 2008, http://www.redorbit.com/news/science/1575336/china_hu_jintao_inspects_anhui_farms_ccp_third_plenum_to/index.html?source=r_science.

- deGategno and Patrick, China, Land of Tainted Milk and Honey, New Atlanticist, 2008, http://acus.org/new_atlanticist/china-land-tainted-milk-and-honey. http://www.radioaustralia.net.au/news/stories/200809/s2373173.htm.

- ABC Radio Australia, “NZ milk firm ‘sorry’ for contamination crisis,” 2008c, http://www.radioaustralia.net.au/news/stories/200809/s2373569.htm.

- State Council Information Office, The Quality and Safety of Food in China (White Paper), 2007, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2007-08/18/content_6032837.htm.

- Ang, Audra, UN Urges Improved Food Safety for China, Yahoo News, 2008, http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20081022/ap_on_re_as/as_china_tainted_products.

- AFP, UN Urges China to Revamp Food Safety after Milk Crisis, 2008b, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_kmafp/is_200810/ai_n30920744.